I. Setswapong

By

Pnina Motzafi-Haller, Klaus Keuthmann

andRainer Vossen

General introduction

Setswana is both the national and the only official African language of the Republic of Botswana. It is spoken as a first language by roughly 75% and as a second language by less than five per cent of Botswana's population. 1 A survey of Setswana dialects was carried out between 1992 and 1994 as

part of a research project on language and identity within the framework of the Special Research Programme 214, "Identity in Africa", of Bayreuth University, Germany. 2 The point of departure was an observation made in a previous project on language knowledge and language use: a large number of interviewees had answered our question "What languages can you speak?"

by using names of Tswana merafe ('tribes, chiefdoms'), prefixed by the se- formative expressing 'language, culture, way of life', and thus suggesting

"Sekwena", "Sethlaro", "Selete" and so forth to be languages or dialects in their own right. In the absence of reliable sources 3 on the language/dialect situation of Setswana, we came to the conclusion that a country-wide survey

1 Based on most recent census data, we estimate the total population to be about 1.5 million, of which 1.13million are first language speakers of Setswana (according to non¬

governmental sources). Taking together all available data, the number of additional sec¬

ond language speakers sums up to no more than 67,000.It thus turns out that nearly 20%

of the population of Botswana (particularly people of European, Khoisan, Ndebele and Shona origin) do not speak the national language.

2 We wish to express our gratitude to the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation), who generously funded the project, and to the Office of the Presi¬

dent of the Republic of Botswana for giving permission to carry out this research.

3 To the best of our knowledge, there are still but two short contributions on the dialectology of Setswana, dating back to the 1930s and 1960s respectively: Tucker (1932) and Malepe (1968). Tucker writes, inter alia, on Setlokwa and Sekgatla, while Malepe ventures a provisional classification of Setswana dialects. A brief and preliminary report on the project presented here was published by Vossen & Keuthmann (1995).

was needed in order to find out about the "linguistic reality" that was hid¬

den behind those labels.

Given the large size of Botswana on the one hand and a limited time frame on the other, it was clear that a highly diagnostic research instrument would be imperative to cover all of the country in a satisfactory way. As only a linguistically trained native speaker of Setswana was capable to appraise the diagnostic factor, Dr. Joseph Tsonope of the University of Botswana was invited to actively cooperate in the project. Then a questionnaire consisting of three parts was designed: the first part inquired about the biographical background of the interviewee, the second comprised a 100-wordlist, and the third part dealt with a short narrative text on a topic of the interviewee's own choice. This questionnaire was first tested in two different districts of Botswana (Chobe and Southeast), after that it was slightly modified and finally employed throughout the survey.

The present article is the first part in a series of individual descriptions of Setswana varieties, as they crystallized from the altogether 147 interviews that were conducted all over the country (see Maps 1-3). The descriptions focus on sound systems and some lexical characteristics, but questions of intra-dialectal variation and its likely causes will also be tackled.

The Tswana who, according to linguistic and socio-cultural criteria, con¬

stitute part of the more inclusive Sotho-Tswana category of Southern Bantu speakers, are believed to have entered central-southern Africa some time before 1600. A process of fission and expansion of these migrating groups produced several merafe which formed and dissolved in the course of the two centuries following the entry of these groups into southern Africa. The instability of these early political structures led to constant movement, seg¬

mentation, and reconsolidation of groups, which produced an overall cul¬

tural unity among these early migrants. Fission and expansion gave way, towards the early 18 th century, to a process of amalgamation and, by the end of the century, to the emergence of several centralized state systems (Legassick 1969). These early polities, which thrived on trade with the east coast, were torn apart during the first half of the 19 th century by revolution¬

ary political and economic changes known in the history of the region as the

"Difaqane wars" (Parsons 1982, p. 55ff., Omer-Cooper 1969, Hamilton 1995). The newly reconstituted 19 th century states were based on the mili¬

tary power of the core ruling groups who conquered or incorporated other groups into a centralized political system (Parsons 1974, Schapera 1970, Wilmsen 1989).

When British control was established over what came to be known as the

"Bechuanaland Protectorate" in 1885, the local population was organized

morafe, was headed by a monarch (kgosi, also translated as 'chief or 'king') and occupied its own territory. The population of each polity was ethnically diverse, but the ruling communities of the various polities were all of inter¬

related Tswana groups (Schapera 1952, pp. 8-11, 1984 [1953], pp. 14-16, Sillery 1974, pp. 6-10).

Towards the end of the 19 th century, several features of this political and territorial organization underwent considerable change. After a long pe¬

riod (c. 1820-1850) of civil unrest and confusion, the reconstituted polities reached the limits of their outward expansion and began to consolidate their rule over their respective territories. Several improvements were made in the system of rural administration and tribute extraction from subject peo¬

ple was introduced in the northern polities (Parsons 1973, Schapera 1970).

The control over subject groups in the peripheries became more effective as resident, rather than visiting, governors became more common. Several rulers introduced a series of reforms which improved the economic posi¬

tion of their subject population. Schapera reports that the Ngwato king Khama, soon after gaining power in 1875, prohibited the sale of "Bushmen"

or Sarwa serfs (Botswana National Archives, HC 24/15). A decade later, he advocated that serfs should be paid for their work and be allowed to own property (Schapera 1970, p. 89f.). Among the Bangwaketse, Gaseitsiwe allowed Bakgalagadi serfs to own cattle, and Sebele I, ruler of the Bakwena, renounced his claim to tribute from serfs in his territory (Schapera 1970, pp. 46, 90, 183, 225).

The boundaries of the "tribal reserves," established under colonial rule, were by and large kept and constituted the post-independence administra¬

tive units, the districts.

1 Introduction

"The Bachwapong and Bakalahari speak a dialect of Sechwana and are of lower and inferior rank; many of their chiefs own flocks and herds and they are to be distinguished from the still lower Masarwa by these possessions and the cultivating of gardens." 4

4 In this statement, the Deputy Commissioner Sidney Shippard (cf. Botswana Na¬

tional Archives HC 24/15) used the designation accepted by the ruling group. From this perspective subjugated groups like the Batswapong or the Basarwa are referred to with the ma- prefix rather than ba-. ba- is the proper prefix for people, ma- is often used for inanimate objects and for subjugated collectives.

This Statement was made in 1888 by a British colonial officer, who made a link between a group of people known collectively as "Bachwapong", their social rank vis-à-vis other Tswana groups, and the relationship between the language spoken by this people of "lower and inferior rank" and Setswana ("Sechwana"). As part of a general linguistic survey of language and iden¬

tity in Botswana, Klaus Keuthmann and Rainer Vossen set out to the Tswapong Hills region in 1993 with the same question that linked group identity, social hierarchy, and language. Is there a Setswapong language spoken by Batswapong people? Or are we dealing here with a dialect of Se¬

tswana? And who are those Batswapong who are said to be distinguished by the use of this dialect/independent language? In 1993, just about the time of Vossen and Keuthmann's field excursion to the Tswapong Hills region, Motzafi-Haller published an article in Botswana Notes and Records in which she raised this very question: "Who are the Batswapong?" In this

essay, and in her 1988 PhD thesis, Motzafi-Haller maintains that the answer to this question is not simple and that it underlies the shifting con¬

stellation of the three interlinked components mentioned in the above state¬

ment. Collective identity and linguistic behaviour are directly linked to so¬

cial hierarchy and the continuous attempts to disrupt and renegotiate social boundaries. In other words, the very claim to a "Batswapong" collective identity and, inter alia, to the argument that the language spoken by these Batswapong people is a distinct language, and not a dialect of the national language, Setswana, is part of specific processes of defining and contesting social hierarchies. And these processes, as the brief summary of the regional social history presented below will suggest, are historically constructed. A brief illustration of this point is the experience Motzafi-Haller reports about her early 1980s work in the Tswapong region. In the early 1980s, very few people in the Tswapong Hills region were happy to describe themselves as Batswapong. In one court case a young woman took a Birwa man, resi¬

dent in Maunatlala, to court because he insulted her by calling her a mo- tswapongyana - a diminutive term of a Motswapong person. When asked directly if they speak Setswapong, people noted that Setswapong was once spoken in these hills and that today only a few elderly people, particularly those who reside in the villages of Moremi or Lesenepole, still know that language. All other residents of the Tswapong Hills region insisted that they speak plain Setswana - that nothing distinguished their way of speaking from other Setswana speakers elsewhere in the country. People did mention

a few words that they knew to be of Setswapong, rather than Setswana, ori¬

gin. Yet all Motzafi-Haller's efforts (admittedly informal and largely un¬

systematic) to record these words that were said to distinguish Setswapong

more like variations on the way the word was pronounced rather than like

a different word. For example, people often noted that the word for a dress, which in Setswana was pronounced mosese is pronounced mocheche in Se- tswapong. People also joked about the exclamation go (pronounced in a gut¬

tural sound derived from the Afrikaans spelling of cg') which was said to typify Setswapong-speaking people and mark them as witless folk.

Another common argument encountered in the 1980s was that "pure" or

"real" Setswapong is more likely to be spoken in the village of Moremi and perhaps in Lesenepole, and more generally by people of Pedi origin. All the other many residents of the Tswapong Hills, who might have accepted their designation as "Batswapong" on a partial and reluctant basis, rejected the proposal that what they spoke in their daily interaction was anything but Setswana.

By the early 1990s, this politics of identity had dramatically changed as people became more explicitly comfortable with using the label "Batswapong"

as a self-referent. In the national radio one could listen to a programme fea¬

turing "traditional songs of the Batswapong", and school textbooks began to mention the Batswapong as one of the many ethnic groups belonging to the Tswana national tapestry of groups (see Motzafi-Haller 2002). The inter¬

views that provided the data for the linguistic analysis presented in the rest of this essay were carried out during this newly created context of ethnic pride and a sense of a national legitimacy to internal, unthreatening articulations of particular group identities. The interviews were carried out in the villages of Lerala and Ramokgonami, two of the centres of "Pedi" people, whose identification with the collective identity "Batswapong" is the most promi¬

nent. To understand this notion of internal variations within the Tswapong Hills population and the extent of identification with "Tswaponghood" we must turn to a brief social history of the region and its peoples. This brief overview underscores our original interest in the relationships between col¬

lective identity, social hierarchy, and language behaviour.

The inclusive label "Batswapong" (often "Matswapong") appears for the first time in missionaries' accounts at the critical moment in the history of the region, around 1860, when the regional population came under the cross¬

fire of two rising centralized powers, the Amandebele to the northeast of the region and the Bangwato to its southwest. In these early accounts (Mac¬

kenzie 1871) and in historical compilations largely based on these accounts (Schapera 1952, 1970; Sillery 1974; Parsons 1973), the population of the Hills is described as industrious and defenseless iron workers and cultiva¬

tors who could not effectively resist the military might of the expanding

Ngwato lineage coming from the south. Oral evidence recorded in the early 1980s by Motzafi-Haller in the Tswapong Hills suggests that residents of the Hills had never attempted to resist Ngwato domination and that, in fact, they had invited Ngwato protection against the more destructive raids of the Amandebele armies.

During the first two or three decades of domination (c. 1840-1870), and while the Ngwato lineage was consolidating control over its expanding ter¬

ritory, the population of the Hills was accorded a large measure of local autonomy; tribute in the form of wild animal skins was a symbolic token of deference to a higher remote centre of power.

The "subject tribe called the Machwapong", writes one missionary in the late 1860s, "renders a certain tribute to the Bamangwato, but are permitted to enjoy, after somewhat precarious fashion, their own flocks and herds and other property" (Mackenzie 1871, p. 366).

In the historical process that defined relations among Ngwato rulers and the various ruled populations, each developed a new awareness of its dis¬

tinct collective identity. In the dominant discourse of the ruling Ngwato, the population was divided into free citizens and vassals. Free citizens were members of other Tswana polities who joined the Ngwato core due to ag¬

natic competition and segmentation. These batlhanka were integrated into the nesting hierarchy of political units as wards, sections, and age-sets. Vas¬

sals, like the conquered population of the Tswapong region, were kept apart as locally independent yet materially exploited subjects. At the bottom of this differentiated hierarchy of groups were Basarwa ("Bushmen"). The population of the Hills was just a step above that of the Sarwa serfs. Like the Bakgalagadi, they were allowed to own property and to be ruled by their own chiefs as long as they raised tribute to the Ngwato centre of power. To¬

wards the last quarter of the 19 th century, the Ngwato king had established an effective system of administration by positioning his own relatives and trusted commoners as resident governors in the region and by systematizing tribute collection. In 1896, a visitor to the Tswapong region (Willoughby 1898) reported: "all these villages are placed under Bamangwato who collect taxes from them."

2 Research on Setswapong

Published information on Setswapong is very scarce; documentary sources do practically not exist. Passing remarks scattered over a few non-linguistic publications are too little to put us in the picture as to the linguistic status

scholars consider Setswapong an independent language, 5while others rather class it with Setswana. The present authors belong to the latter group of scholars. They strongly hope that the presentation of the overall dialecto- logical situation in Setswana (to be published later as a monograph) will settle the controversy about the status of Setswapong or, at least, contribute to its termination.

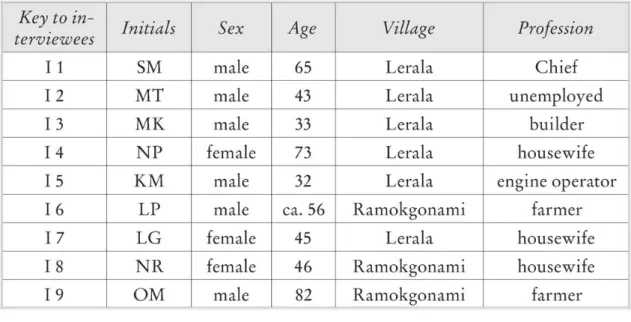

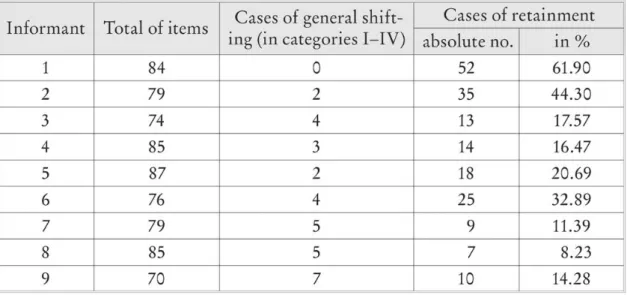

The collection of Setswapong data took place from 20 th to 22 nd August 1993. All in all nine interviews were conducted in the villages of Lerala (6) and Ramokgonami (3; see Map 4), with Setswana as the medium of commu¬

nication. All interviews were recorded on tape and were later on transcribed.

Six of the interviewees were men and three were women; they were between 32 and 82 years old. For reason of anonymity only the initials of the inter¬

viewees' names are given in Table 1 below:

Table 1: Setswapong interviewees 6 Key to in¬

terviewees Initials Sex Age Village Profession

I 1 SM male 65 Lerala Chief

12 MT male 43 Lerala unemployed

13 MK male 33 Lerala builder

14 NP female 73 Lerala housewife

15 KM male 32 Lerala engine operator

16 LP male ca. 56 Ramokgonami farmer

17 LG female 45 Lerala housewife

18 NR female 46 Ramokgonami housewife

19 OM male 82 Ramokgonami farmer

5 In a recently published lexicostatistical classification of Bantu languages of Bo¬

tswana, Batibo (1998) integrates Setswapong (together with Sebirwa [=Northern Sotho]) within the Sotho-Tswana group of Southern Bantu, side by side with Sekgalagadi and Se¬

tswana. This allocation is based on percentages of shared vocabulary between 72 and 90.5 for the Sotho-Tswana group as a whole. The cognate share of Setswana and Setswapong was calculated to be at 86 per cent. Batibo does not, however, present the data itself on which the calculations are based, nor does he show what word pairs he considered to be cognates. In fact, nothing is said about the data basis at all so that his findings can in the last analysis not be assessed.

6 We are much indebted to all our informants for their collaborative attitude and kind assistance in compiling the data basis for this study.

3 Linguistic description

The presentation of the linguistic data is both practically- and scholarly-ori¬

ented. Its major aim is to give an approximate idea of some phonological, morphological and lexical characteristics as well as to outline some traits of Setswapong-internal dialect variation.

3.1 The data base

In this section, the linguistic corpus of data will be presented as it occurs in the collected wordlists. The following principles of presentation have been applied:

(1) All lexical items contained in the 100-wordlist are arranged in the al¬

phabetical order of English glosses; they are numbered consecutively.

For Setswapong equivalents, underlying forms are represented on an abstract level: frequent ones in italics, less frequent forms in normal type. The spelling of all forms follows the orthographic conventions of 'Standard Setswana".

The phonetic transcriptions of all recorded equivalents take into ac¬

count the diverging degrees of pronunciation. They are put in square brackets and are placed after the underlying forms. Reference is made in each case to the interviewee(s) from whom the form(s) was/were ob¬

tained (e.g., 12,14-7, etc.).

The following diacritics are used:

(2)

(3)

(4)

primary stress secondary stress apical realization devoicing

voicing

open/lax vowel quality (e.g., ô = o)

b ß f *

palatalization (e.g., s = J)

Table 2: The diagnostic 100-wordlist

No. of item English gloss Abstract forms Phonetic forms

1 abscond (go) ngwêha [(xo/ho) nweha (12-5/7/8);

(xo) nwsxa (11/6)]

afterbirth (human) thdri [thari (13)]

2

afterbirth (animal) mothâna [mothana (12-9);

mothlana (11)]

3 ascertain truth (go) rurïfâtsa [(xo) ruri(j)atsa (11)]

4 back of the body mokwâta [mokwata (12-9);

mOKW3 1"13 |T1 )1 iiiuiv W aLia 111 J \

5 birth-mark

a. tshubâba

n lpnpplá VJ• ICULLla

c. kéleswà d. bïisô e. semáata

[tshußaßa (13/4/7/8); tshu¬

bâba (12); letshußaßa (15)]

rledela (15 VI

llV^VJ-V^ldl-L^/J

(16)

[biiso (19)]

(II)

6 bottle leb ótele

[leßoteh (13/5/8); leßoteele (14/7); leßotili (19); lebotele (11/2); lebotili (16)]

7

bow, musical ~

(träfutinnä 1çin-

\ L-LCLvA-LLlWlldl Olli

gle-stringed in¬

strument played with a bow while being rested on the shoulder)

a. cebaba b. motorópo c. sehánkuru sérankùri d. kàtàra

[cehaßa (18); sexaba (11/2);

sexaßa (I5YI

OV^-¿vCLK-/<X1 IJ /

[motoalopo (14); motoropo (16); motohopu (17)]

[sehankuru (13)]

[serarjkuri (19)]

(17)

bowl, wooden ~ mohópu [mohopu (16); mohopu (19)]

8

~ (small)

a. mohotswâna b. sekûtîjâna

[mohotswâna (12-5/7);

moxotswana (II)]

[sekuti3ana (18)]

9 nrP3Ul V^uJ\ V'*/le i V )

a. (ho) thûba b. (ho) cinya

[(ho) thußa (13-9); (xo) thuba (11/2)]

[(ho) cijia (19)]

10 brew (beer) (v.)

a. (ho) i/zra (bojdlwa) b. (ho) ridêlêla

f* i ero i npniçii v^. Vs^'-'y L-'v^vj.ioci

(bojálwa)

[(ho) dira / c[ira / c[iha (ßo[d] 3alwa) (13/7-9)]

[(ho) ritstsla (14); ridslsla (15)]

Imtoi npniçii ( nn In 1t.c\ Iw3 i Il AU 1 VJ\^\X\-0<XVVJ\J 1VJ.J *\(XíW (XI

(11/2)]

11 brother/sister, elder ~

a. nkónu

b. mogol(lelî)

[rjkuni (13/5); nkoonu (18/9);

nkunne (II); nkonno (12);

nkooni (14); nkonu (16);

nkonne (17)]

[moxole (II); moxolleli (16)]

12 calabash, beer ~

phâfàna

[phâfàna (11-4/6-9)]No. of item English gloss Abstract forms Phonetic forms

13

calf a. namânî

b. 1erole

[namani (11/4/5/8)]

[lerole (12/3/7); leroli (19)]

~ (younger than

six months) lêbotâna [leßotana (14/6/7); leßotana (15); lebotana (II)]

14 castrate (no) îahoia/1 \ -Tv J '1

[(ho) Vahóla (13/7-9); (ho) (j)a(j)ola(14/6); (ho) phahola (15); (xo) Vahóla (II); (xo) (j)a(j)ola(12)]

15 chase (v.)

a. (ho) lelekisa

b. (go) alóla

[(ho/xo) lelekisa (11/3/5-7);

(ho) leleka (14); (ho) lelekisa (18); (ho) lelekisi (19)]

[(xo) alola (12)]

16 clay

a. mmopa n cplohn

KJ• c-t'iy/Viy

c. cebáro

[mmopa (11-3/5/7/9); moopi (14); mmopa (16)]

Iceloko (14)' seloko (15/6)]

I vLlv/lvJ I IT u OLlv/l\v \-L^s/ \J yl

[tfeßaro (17)]

17

clay-pot a. nkhwána

b. cézoána

[nkhwana (16)]

ha\(14)

pot pïijâ [pii(d)3a (14/7-9); pitsa (11/5);

piitsa (12)]

18 coal(s) (ember) mahâla [mahala (13/4/8); maxala (II)]

~ (mineral) malâtha (12/5-7/9)

19 cockroach

lefêne lefêle

[lefêne (12/5); lefeni (14);

le^ene (19)]

[lépele (13); le^eb (17)]

20 cold(ness)/winter

a. mariha b. botsididi c. cêrêmê

[mariha (12/5/7/9); marixa (14)]

[letsididi (II); ßotsicjicli (13);

ßutsiciicii (18); ßotsididi (19)]

[cereme (19); serame (16)]

21 corpse

a. cètopô b. setoto

[setopo (11/2/4/7); setoopu (13/5); ceto:po (18)]

(II)

22 cruelty

a. bûpîlûmpî b. (bo)swèlî c. (bo)sethóho

[büpilumpi (11/6); bopelumpe (12); ßöpibmpi (15)]

r „ T 1„ /Ti\, 1 ^ „„„^1.. / T/1\.

[swell (13); bosweeli (14);

ßoswili (15); swih (17)]

[bosethoxo (16); sethoho (17);

ßosethoho (18)]

23 cultivate/ plough

a. (ho) lerna b. (ho) lemolóla

[(ho) lema (12-9); (xo) lema (H)]

(17) z4i /i aimculty

a. mathâta b. molâtû

[mathata (14-6/8); bothata

^^4-U^ J ^ /T1M

(12); matnada (13JJ (19)

25

dig out (miner¬

als/pot clay/hon- eycombs)/take out (grain from

a bag)

(ho) rafa

r/1__\____ i „ /ti /c n\. /1__\

[(no) racpa (13/5-9); (no) raacj)a (14); (xo) racj)a(II); (xo) rafa (12)]

26 dog mpsâ

[mpja (14/6/7); mmpja (18/9);

mpsa (H/2); mmpsa (13);

mptja (15)]

27 dove

a. leéba b. lekùnkuru

[leeßa (12-5/7/9); leiba (II);

hiba (16)]

[lekunkuru (18)]

28 drought

a. leúba b. nako ya

komêlêlo

[leußa (12/5/7)]

[nako ya komslslo (II)]

29

eagle (bigger member of the Aquilidae)

ntsu [ntsu (11-5/7); ntshu (16/9)]

30 fever/malaria

a. letshoróma b. lekokû c. bodêdêma

(11/2/5/6) [lekoku (14)]

[ßodsdsma (18)]

31 fight (v.) (ho) Iwa [(ho) lwa (13/4/6-9); (xo) lwa (11/2); (ho) b (15)]

32 flank of body

a. letsâtsa b. lethàkore c. mháma

[letjatja (11-3/5-9)]

(14) (15)

No. of item English gloss Abstract forms Phonetic forms

33 foam lefulo [lecjmlo (11-3/6-8); lehulo

(15/9); lecjmb (14)]

34 folk-tale

a. leínaní b. náaní

[leinani (11/3/5/6/9); leinane (14/8)]

[naani (12/7)]

35

Tr\ r\i~ 1n't

1UULUI 1111 inn r\t I/i/i 1sirrl-ULrJClLCl /T1 _Q\

{Li y)

spoor of a carni¬

vore 1er oo (11-3)

36 germinate

a. (ho) thóha b. (ho) mêla

[(ho/xo) thoha (12-5/7/8);

(ho) tho(j)a (16)]

[(ho/xo) mêla (11/3/4/7/9);

mila (16)]

37 gonorrhoea (ve¬

nereal disease)

a. rasèphiphi b. totonû

[rasèphiphi (11-5/7/8);

rasiphiphi (16)]

[totonu (19)]

38 granary

a. cefdld(na)

r\ í^o "V/11/1 U. LClClLCl

c. lethàabi d. letólo

[secj>alana (13/5/8); cébala (14)]

I cpri m (11_ ^ / S _/ i • r"Pi*i m Locidid ^ii—j/ J —/y, cci did (14/8/9); cehaha (19)]

[lethaaßi (16-8)]

(16)

39 grandmother bókokú [bokoku (14-7/9); bokoku

(11-3); bokoku (18)]

40

grind (into meal) (go) sila [(xo) sila (II)]

stamp grain (ho) seta

lYVin/Wï çpts fT?-S/7/8V ÍyhI

L^llU/ XU j oCLd ^IZ. ~>/ / / Oy , ^AU y

setla (II); (ho) sita (16)]

41 harvest (v.)

a. (ho) roba

v\ I n a 1 k"f\f il M U. ^llUy ivUllAld,

[(ho) roßa (13/4/7/8); (ho/xo) roba (II); roba (12); roba (19)]

\ ÍD)

42 hat «1 l/11j1~cl/10<x. rJWLSrJC

b. thóro

rVmi-çVip fTi-s/7/8V Vini-çVn n&xi

LIIUIMIC ^11— J/ //Oy, IlUlMll ^ioyj

(11)

43

home

a. mos¿¿

b. lei(w) dpa c. (le)háe

[moja (11); mooja (14);

mojaja (15); mojana (17)]

[lelwapa (11/6); lelapa (12)]

[lehae (18); haae (19)]

village mótse [motse (13/4/7); motsi (15/6)]

yard jarata [(d)3áratá (16-9)]

44 hoopoe mordkapula [morokapula (12—5/7); moro- kaapula (11/6); moroka (18)]

45 hut

a. ntwdna ñtu(nyána) b. mohobi c. mokgoro

(11/2/4/8)

[nthu (13); ntunana (17); ntu (19)]

IVnrw^Ri (1A\- t-n/->l-i/->Ri (17W

[moxopi monopi \l/ )\

[mokxoro (16); kxoroana (14)]

46 inspect

a. (ho) lèbaléba

(ho) sêbasêba b. (ho) sékasèka

[(ho/xo) lebaleba (11/6);

iUr^/vr^\ I^Rnl/^Rn ÍJO ll /QV íUr^\

\Lio/xo) lepaiepa / 1y), \tio) hßahßa (14)]

[(ho) Jsßajsßa (13/8)]

[(ho) sekaseka (15)]

47 intestines,

cc\d KpH miYpn ~ CUUI\LU 1111A^VJ

ce robi

[ceroßi (14/8); seroßi (16/9);

serobe (II); seroßs (12);

seroßs (15); tjeroßi (17)]

48 J2CW Í-CVlJiA/iJtA/Ipth/7 h/7 [lethaha (12/3/5-7/9);

lethaaha (14/8); letlhaa (II)]

49 land/country

a. lefâtse b.

[le(j>atse (12-5/8); le^atsi (16/7); lehatse (II)]

[neha (13/4/7/9); naxa (15)]

50 IClllcL LlClclV^1c\ncnic\crp Z.pHO

b. lelémî

[puo (12/3/7/9); puwo (15)]

[lelemi (11/4/8)]

51 maize mmídi [mmicii (13/4/6-8); mmidi

(11/2/9); mmidi (15)]

52 marry

a. (ho) jeyd b. (ho) rajtf/tf

rtUr^\Avwi ÍJ7 qv l{no) ü3sya (no;

d3ssya (13-5); (xo) tsaa (II)]

[(xo)jiala (11/2/6)]

53 meat, stewed and stirred ~

cès'zxw

lèswào

[seswae (12/5/6/9); seswaa (II); ceswai (14); tfeswae (17);

ceswae (18)]

(13)

54 menstrual period of a girl, first ~

a. (ho) ithàlêha b. (ho) rafóla c. (ho) ralêha

[(ho/xo) ithalsha (12/4/9);

ithwalsha (13)]

[(ho/xo) rafola (II); racola (16); rahola (18)]

[(ho) ralsha (15/7)]

No. of item English gloss Abstract forms Phonetic forms

55 mock (v.)

a. (ho) sota b. (ho) khôba

[(ho/xo) sota (11-3/5-9)]

[(xo) kxoba (II); (ho) khoßa

fT4YI

56 money maadi [maac[i (13-9); madi (II);

morli fT?YI iiiacii \-L-¿

57 mumble (v.)

(\^c\\

\no)

ngunanguna

1i ri t~\1~\rr\ i nnii'iniiii'i

L^no/xoy rjunarjuna (11/2/7/8)]

whisper (v.) (ho) sêba [(ho) ssßa (13/5/9); seßa (16)]

JO navel mokhúbu [mokhußu (14-9); mohubu

(11/2); mohußu (13)]

59 neck molal a (11-9)

60 needle/awl

a. nnâlêtê b. nnâlî c. thóko

[nnalsts (12/8); nnalste (13/9); nnslsts (14)]

[nnali (15-7)]

(11/5/9) 61 ostrich (Stvutw

camelus) mmps(h)é

[mmpshe (11/2/5); mmpse (14/8/9); mmpshs (13);

mmampse (16); mampse (17)]

62 owl (Bubonidae)

a. lekó(o)da b. lerubisi

[lekooda (11-5/7); lekoda (16/8/9)]

(^\\

63

ox -/il/ir\ Ir\UtJOLO l~nhr»1r» fî1 /ï/^/7 9V nhrslrs fTAYI

LpilUlU yli/J/D// —yjy ulLUlU ylOJ^

pack-ox a. lekába

b. pèlesà

(12) (14) 64 path/road/cattle-

track

a. mmilâ

b. £se/¿¿

(11/2/4/5/7/9)

[tsela (13/5/8/9); tsila (16)]

65 person, guileful ~ lefèrefére [lecheree})ere (17/8)]

66 praise (v.)

a. (ho) ¿?ó&¿¿

b. (ho) rêta

[(ho/xo) ßoka (16/7/9); boka (II); (ho) ßoka (13/5/8)]

[(ho/xo) rsta (12/4)]

67 pumpkin

a. lephutshî b. lènthwê

[lephutshî (11-3/5/8/9);

lephutsi (14); liphutshi (16)]

[lenthws (17)]

wild water-melon lerôje [lerotse (13); lerod3s (17)]

68 quickness

a. bofefu b. bonâko c. kàkofu d. kàpîla

[bo(j)e4)ü (11/2); ßocj)e(j)ü(15)]

[bonako (II); ßonako (14/5)]

[kàkofu (16)]

[kapila (17)]

69 rob

a. (ho) swâda b. (ho) khothósa c. (ho)

thukhutha

[(ho) Jwada (13/6); swada (17/9)]

[(ho) khothosa (18); (ho/xo) kxothosa (11/4)]

(15)

70 run away

a. (ho) szj¿¿

b. (ho) tshâba

[(ho) siya (16-8); siana (18);

(xo) siya (11/2)]

[(ho) tfhaßa (13-5/9); (xo) tshaba (11)]

71 scoop/hollow out

a. (ho) haba b. (no) tsenavX

[(ho) haßa (15/9); (xo) xaba (11); haba (12)]

[7VirV\ tfcVid fT^YI

[^no; tjsna yij)]

72 shake (v.)

a. (ho) sïkinya (ho) tshï- kinya b. (ho) rèkéta

[(ho) sikina (17/8); sikina (19)]

[(ho) tshikijia (13)]

[(ho) reketa (16); (xo) reketla (11); (xo) reksta (12)]

Ä, rtfiû C

~ one s Douy I r\ /"\ i niifï'lniifï'l^noy uegaciega \\Liij) Qsgau-Sgarlccrcirlco-ci ÍU/^Myi//ojj 73 shelter, small

temporary ~

mosdna mosasá

[mo/ana (13/6-8); moja(jana) (19); mosasana (11)]

[mojaja (15); mojaaja (14)]

74 sleep (v.)

a. (ho) otsêla b. (ho) robála

[(ho/xo) otssla (13-7/9); (ho) otssla (18)]

[(ho/xo) roßala (12/3)]

75 small-pox

a. sekhwàri- pâna

sekgwarî- kgwárí b. bogwáta

[sekhwaripana (11/8);

khwaripana (14); sekxwari- pana (12)]

[sekxwarikxwari (17)]

[boxwata (15)]

76 smoke (tobacco) (v.)

a. (ho) hoha

b. (ho) péipa

[(ho/xo) hoha (12/3/7/8); (ho) hoxa (16); (ho) hoha (19); (xo) xoxa (11/4)]

[(ho/xo) peipa (11/5)]

No. of item English gloss Abstract forms Phonetic forms

77 snore

a. (ho) khórótha b. (go) óna c. (ho) lora

[(ho) khorotha (19); (xo) kxorotla (II); kxorota (13);

(ho) kxorotha (15-8)]

[(xo) ona (11/2/4/6/9)]

(13) 78 split (fire-wood)

(v.) (ho) phâtsa [(ho/xo) phatsa (11-5/7-9)]

79 theft bohódu [boxodu (II); bohodu (12);

ßohocju (15); bohocju (16)]

80 thorn muútwa

[muutwa (13-5/7/8); mutwa (II); moutwa (12); muutfwa (16); muutswa (19)]

81 thumb

a. monwâna b. khonópe

[monwana (14/5/9); monwana (16/8)]

[khonope (16/8); khunupi (II); xonope (12)]

82 tick khófa [kho(j)a (11/3-8); kxo^a (12);

khoha (19)]

83 tin

a. cebâhabïki

b. torómole c. thini d. kokóko e. káaní

kantí f. sebikïri g. dùruduru

tsethù- ruthuru dùnduru

[seßahaßiki (12/3); ceßahaßiki (14/8); sebahabiki (II);

cißahaßiki (16); tjeßahaßiki (17); sebahaßiki (19)]

(13) (14) (15)

[kaani (16)]

(19)

[seßikiri (15)]

[duruduru (16)]

[tjethuruthuru (17)]

[dunduru (18)]

84 tree/fruit, buf¬

falo-thorn ~ mokhâlo

[mokhâlo (11/3/5); mokxalo (12/4/7); mokhab (18/9);

dikxab (16)]

85 tree,

camel-thorn ~

-i -W7r\ l/ir\ i~l/ir\

a. TTTOuOluO

b. mokála

ímAn^tliA (T^/^/Qi* tYiAvnfnn

Lmonjtno ^ij/j/oy, moxotno (12/6); moxotho (14); mo- hotho (17/9)]

(II)

86 truth

a. boâmmaarù- ri

b. nnétî

[ßoammaaruri (13/4/6-8);

boammaaruri (11/2/5)]

[nneti (15)]

87 ulcer thàhâla [thahala (11-5/7-9); thayala

(16)]

88 umbrella

a. cekhúkhu b. sdmpûrè(ng)

[sekhukhu (12/3/5); cikhukhu (16); cekhukhu (18)]

[sampurii (II), sampure (14);

sampursh (17); sampurerj (19)]

89 urine rnoróctoIl yV/l V/WV/ [morodo (13-9); moroto (11-2)]"

90 visitor

a. moyé(e)ng b. moéti

[moyeen (14/5/7); moyen (16/8); moen (12/3)]

(11/4)

91 walk (v.) (ho) tsamdya [(ho/xo) tsamaya (11-8);

tsamaa (19)]

92 wall

a. lekotswâna

b. lebodá(na)

[lekotswâna (11/6/8/9); le- kxotswana (12); lekhotswana (13); lekotswâna (17)]

[leßodana (14); leßota (15)]

93 water maâtsi [maatsi (11-3/5/7-9); maatsi

(14/6)]

94 water-melon

a. lehâpu b. lethàlahabu

[lehapu (12/3/5/7-9); lexapu (11/6)]

[lethalahaßu (14)]

95 whirlwind

a. seféfo cefého b. tsútsuána c. matsùkê-

tsukê d. lerúdi

[secj>e(j>o(12/3); secj>e(j>ü (H)]

[serebo (15); secjnhü (16);

tJe4)eho (17)]

(14)

[matsukstsuks (18)]

[lerucji (19)

No. of item English gloss Abstract forms Phonetic forms

96 White a. Lekhóa

b. Mosweú

[lekhoa (13-9); lekxoa (11/2)]

[mojweu (16); mosweu (17)]

97 widow(er)

a. mothôlahâdi

b. moswahâdi

[motholaxadi (11);

motholaxadi (12);

motholahac[i (15)]

[moJVahac[i (13/5-7);

moswahac[i (18);

moswahadi (19)]

98

woman, barren ~

a. cetwà(a)twd

b. moópa

[setwaatwa (13/5); setwatwa (12); cetwaatwa (14); sitwatwa (16); cetwatwa (19)]

(11)

barren animal ceréba [cereßa (18/9); morißa (17)]

99

wood, burning piece of ~ re¬

moved from the fire

a. sestkaldla

b.

cèîsâ

c. serumula d. mötswaiso e. sesána

(11/3/5)

[seisa (16/9); ceesa (14)]

(11) (12) (18)

100 yellow(ness)

a. lèphutshî

b. cèrolwdna

c. -sétha d. borongwána

[lephutshi (11/2/4-6)]

[serolwana (11); moroolwa (13); morolwana (14);

ßoroolwa (17); cerolwana (19)]

[mosetha (14); Boseta (15)]

[Bororjwana (18)]

3.2 Phonology 3.2.1 Consonants

Consonants occurring in the underlying (italicized) lexical forms in Table 2 are shown in Table 3 below. Less frequent occurrence is indicated by pa¬

rentheses.

Bi¬

labial

Labio¬

dental

Alveo¬

lar

(Pre-)

\1 IC J

Palatal Velar Labio-

velar Glottal

Plosives

ejective P (tw) t c k (kw)

aspirated rph11 th kh (khw)

prenasal-

ized mp (ntw) (nk)

voiced (b) d

Ajfn-

cates

ejective (tsw) ts (ts)

aspirated tsh (tsh)

Frica¬

tives

voiceless Ir / \

(sw) s

00,

(sw)

/ \

(g) in

voiced b j

Liquids

rolled r

lateral lw 1

Nasals simple m (nw) n (ny) n g (ngw)

geminate mm (nn)

Glide y

Setswapong consonants distribute over seven places (bilabial, labiodental, alveolar, [pre]palatal, velar, labiovelar, glottal) and six manners of articula¬

tion (plosive, afïricative, fricative, liquid, nasal, glide), making up for a par¬

tially symmetric system.

For plosives, six points of articulation (all except glottal) have been found.

Stops can be voiceless-ejective, aspirated, prenasalized or voiced, p, ph, mp, th, d and kh occur both word-initially and word-medially, h, ntw, c, 7 nk and kw show up word-initially only, t, tw, k and khw are confined to word- medial position. Phonetic realizations: p, t and k are mostly ejectives, viz.

[p' t' k']; d is occasionally apicalized [d], sometimes retroflex [c(J and rarely devoiced [d]; nk stands for [nk].

Affricates show up as labiovelar, alveolar or (pre)palatal egressive sounds.

ts and tsh occur both word-initially and word-medially, whereas tsw and ts are restricted to word-initial and tsh [tfh] to word-medial position, ts and ts are mostly ejective, [ts' tf'].

Fricatives are mainly voiceless; they are found to appear at all points of articulation except labiovelar. With the exception of g, which occurs word- initially only, all fricatives can be used in both, word-initial and word-medial

In our data c occurs in the prefix of noun class 7 (ce-) only.

position. Phonetic realizations: the bilabials/and b are pronounced through¬

out as [<j>] and [ß], respectively; the palatals s, sw and; are realized as [J Jw]

and [d3 ~ 3], respectively; g = [x].

Liquids are either lateral (7 Iw) or rolled (r); they appear at the labiodental and alveolar points of articulation.

Nasals distribute over all points of articulation except glottal; bilabial and alveolar nasals can be geminated. While ng [rj] occurs in all positions, nn and ngw [rjw] are confined to word-initial and nw to word-medial position.

Other nasals occur both word-initially and -medially, n and m are some¬

times syllabic, as in (29) 'eagle' and (61) 'ostrich', respectively.

The only glide found in our data is the palatal y, which is confined to word-medial position.

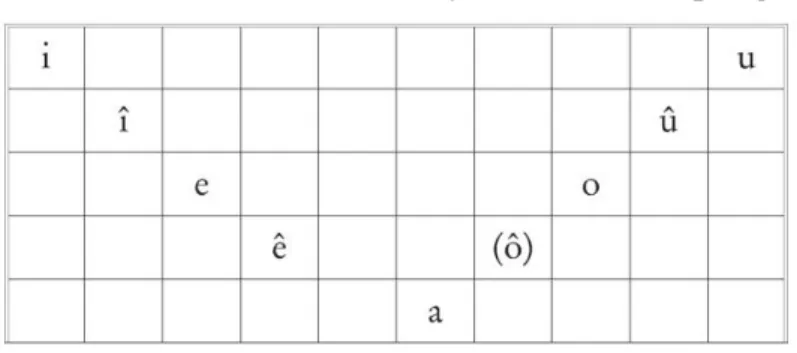

3.2.2 Vowels

Vowels occurring in italicized lexical forms in Table 2 are shown in Table 4 below. Again, less frequent occurrence is indicated by parentheses.

Table 4: The vocalic sound system of Setswapong u

1

û

e 0

ê

(0)a

There are two sets of four vowels each: î [1] ê [s] ó [o] û [0] are lax and i e o u are tense vowels. The low back vowel a is neutral.

Only i and o were found to occur in all positions; ó is restricted to medial position, the rest occur both word-medially and word-finally. Vowel length is attested for all tense vowels and a, partially across word-boundary; cf. (17) 'pot' for ii, (90a) 'visitor' for ee, (38c) 'granary' for aa, (35) 'spoor made by a

carnivore' for 00, (80) 'thorn' for uu.

3.2.3 Tone and stress

Given the scarcity of the data sample, tone could only be noted superficially.

We have therefore decided to leave it unmarked but indicate stress where applicable. Thus, primary stress is represented by ' on top of a vowel, while

v marks secondary stress.

This section describes some major structural elements as occurring in the data sample.

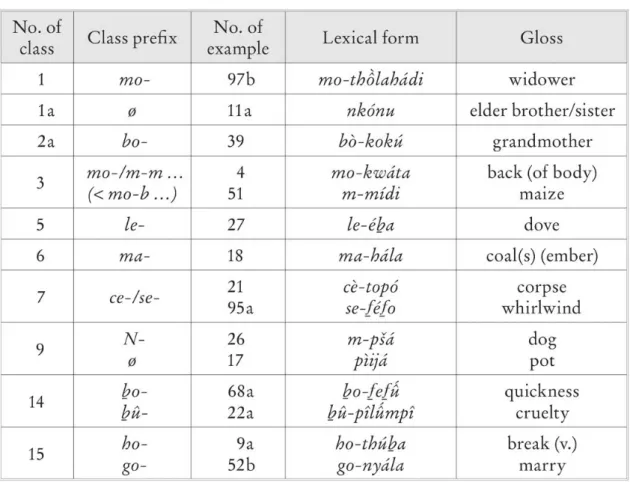

3.3.1 Nouns

Of the 18 noun classes (including la/2a) that exist in Setswana, ten are rep¬

resented in the small number of nomináis contained in our wordlist (see Table 5).

Table 5: Setswapong noun classesas occurring in the data sample No. of

class Class prefix No. of

pyi m ni p

\*A.<XÍÍÍVJi-\*

Lexical form Gloss

1 mo- 97b mo-thôlahâdi widower

la 0 lia nkónu elder brother/sister

2a ho¬ 39 bó-kokú grandmother

3 mo-Im-m ...

(< mo-b ...)

4 51

mo-kwdta m-mídi

back (of body) maize

5 le- 27 le-éba dove

6 ma- 18 ma-hdla coal(s) (ember)

7 ce-/se- 21

95a

cé-topó se-féfo

corpse whirlwind

9 N-

0

26 17

m-psâ

pïijâ

dog pot

14 bo-

bu-

68a 22a

bo-fefû bû-pîlûmpî

quickness cruelty

15 ho-

go-

9a 52b

ho-thúba go-nydla

break (v.) marry

Noun classes 2, 4, 8, 10, 11 and 16-18 are not represented in the data. The first four are missing because they are plural classes which have not explicitly been asked for in the interviews. 16-18 are locative classes that can hardly be obtained through the application of a lexical questionnaire. Finally, 11 is

a noun class that contains just a small number of nomináis in any dialect or variety of Setswana.

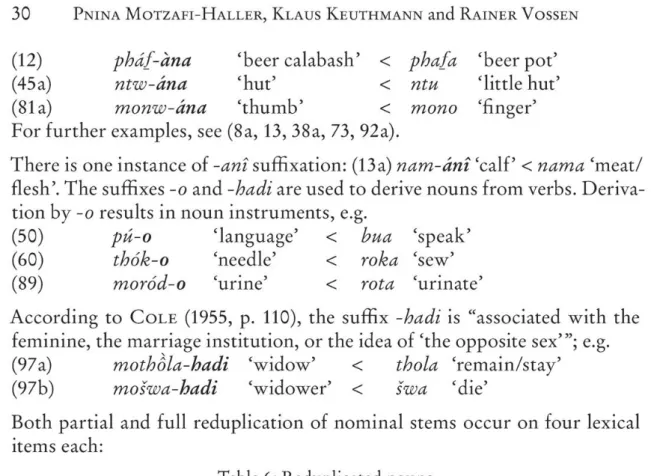

The most frequently occurring derivative suffix in our data is the diminu¬

tive suffix -ana, e.g.

(12) phâf-àna 'beer calabash' < phafa 'beer pot'

(45a) ntw-âna 'hut' < ntu 'little hut'

(81a) monw-âna 'thumb' < mono 'finger'

For further examples, see (8a, 13, 38a, 73, 92a).

There is one instance of -anî suffixation: (13a) nam-ânî 'calf < nama 'meat/

flesh'. The suffixes -o and -hadi are used to derive nouns from verbs. Deriva¬

tion by -o results in noun instruments, e.g.

(50) pú-o 'language' < bua 'speak' (60) thók-o 'needle' < roka 'sew' (89) morod-o 'urine' < rota 'urinate'

According to Cole (1955, p. 110), the suffix -hadi is "associated with the feminine, the marriage institution, or the idea of 'the opposite sex'"; e.g.

(97a) mothôla-hadi 'widow' < thola 'remain/stay' (97b) moswa-hadi 'widower' < swa 'die'

Both partial and full reduplication of nominal stems occur on four lexical items each:

Table 6: Reduplicated nouns

Full Partial

Item no. Lexical form Gloss Item no. Lexical form Gloss

32a letsdtsa flank of body 5a tshubaba birth-mark

65 lefèreferé guileful person 20b botsididi cold(ness)

88a cekhúkhu umbrella 37a rasèphiphi gonorrhoea

98a cetwà(a)twd barren woman 99 sesïkalâla

burning piece of wood re¬

moved from the fire There are at least two compound nouns contained in our data collection, one

consisting of noun plus adjective and the other one being composed of verb plus noun:

(22a) bùpîlùmpî 'cruelty' < pîlu + mpî 'evil-heartedness'

N Adj

heart bad

(44) morokapúla 'hoopoe' < roka +pula 'rain-making' 8

V N

rain-making rain

8 The hoopoe is considered a rain-indicating bird by the Batswapong.

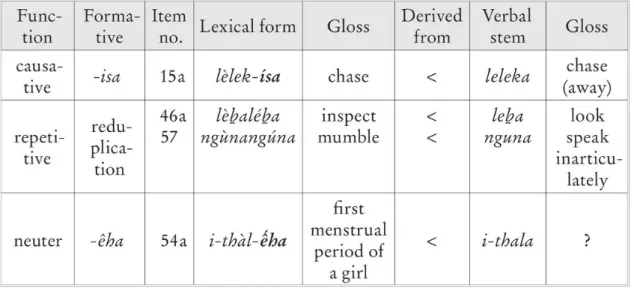

Very few instances of verbal derivative extensions have been found in our data for causative, repetitive and possibly neuter functions:

Table 7: Verbal derivative extensions as occurring in the data base Func¬

tion

Forma¬

tive

Item

no. Lexical form Gloss Derived from

Verbal

stem Gloss causa¬

tive -isa 15a lèlek-isa chase < leleka chase

(away) redu¬

plica¬

tion

46a lèbaléba inspect < leba look

repeti¬

tive

57 ngunangúna mumble < nguna speak

inarticu¬

lately first

neuter

-êha

54a i- thai- êha menstrual period ofa girl

< i-thala }

The last example also attests to the occurrence of the reflexive prefix i-.

4 Setswapong: some chief characteristics and intra-dialectal variation

This section aims at unravelling some chief characteristics of Setswapong vis-à-vis so-called "Standard" Setswana, i.e. Cole's Setswana of the "Cen¬

tral division" (1955, pp. xvi ff.), or simply of the southeast of Botswana and adjacent South Africa. It also deals with variation within Setswapong. The small data sample only allows for conclusions on the phonological and lexi¬

cal levels.

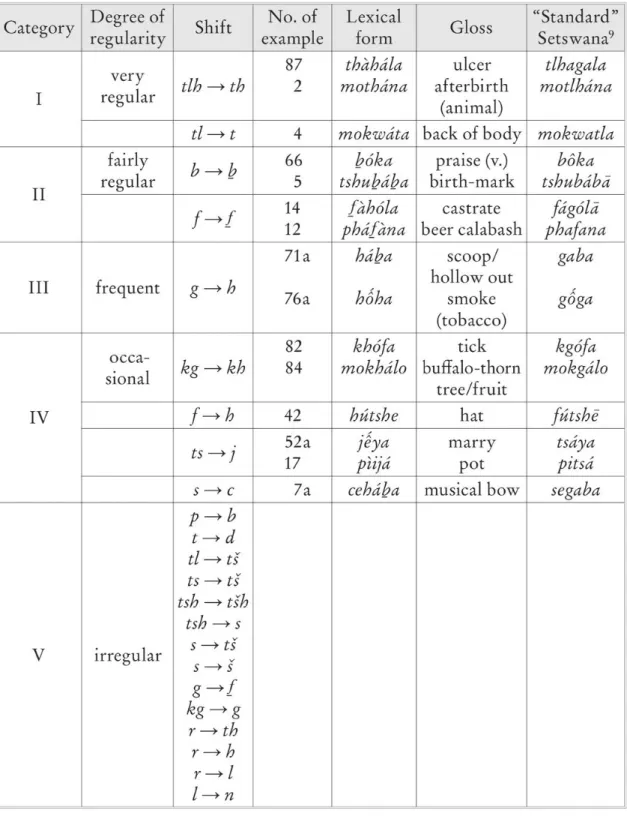

4.1 Some chief characteristics 4.1.1 Phonological features

As vocalic shifts turn out to be mainly singular, we shall confine ourselves to consonantal shifting. The shifts have been arranged in five categories according to the degree of regularity (see Table 8). These categories are:

(I) very regular, (II) fairly regular, (III) frequent, (IV) occasional, and (V) irregular.

Table8: Consonantal shifts Category Degree of Shift No. of Lexical

Gloss "Standard"

regularity example form Setswana 9

very regular

87 thâhâla ulcer tlhagala

I tlh —> th 2 mothâna afterbirth

(animal)

motlhdna tl^>t 4 mokwâta back of body mokwatla II

fairly

regular b^b 66

5

bóka tshubâbâ

praise (v.) birth-mark

bóka tshubâbâ

r s

/w

1412 fâholaphâfâna

castrate beer calabash

fâgolâ phafana

71a hâba scoop/ gab a

III trpmi11 CvJ U-C11Lptit g —> h 76a hôha

hollow out smoke (tobacco)

goga occa¬

sional kg —>kh

82 84

khófa mokhâlo

tick buffalo-thorn

tree/fruit

kgófa mokgâlo

IV

f^h

42 hútshe hat futshëts^j 52a

17

jjêyaj

pïijâ

marryj pot

tsâyaj pitsâ

s —> c 7a cehâba musical bow segaba

p —►b t^> d

tl —►ts

ts —►ts tsh —►tsh

tsh —>s V irregular s —» ts

s —> s

«-/

kg^g

r —» th

r —» h r^l

l—> n

Leaving aside the irregular sound shifts subsumed to category V, it is obvi¬

ous that all other shifts from "occasional" (IV) to "very regular" (I) concern

"Standard"Setswana forms are taken from Snyman,Shole & Le Roux