ARE THE PARENTS OF THE PROPHET IN HELL? TRACING THE HISTORY OF A DEBATE IN SUNNĪ ISLAM

Volltext

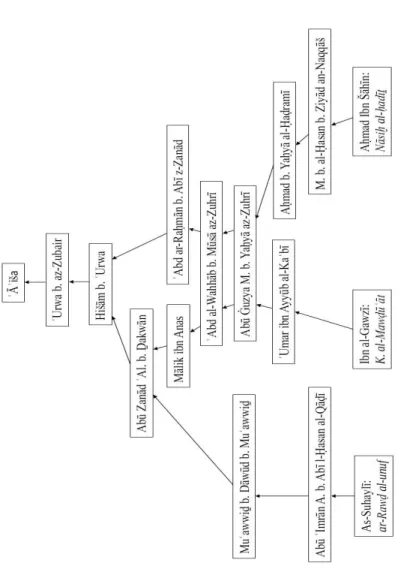

Abbildung

ÄHNLICHE DOKUMENTE

Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy offered political support for the embattled Greek Prime Minister, Antonis Samaras, by visiting Athens before the 25 January snap general election

verschont – sehr zum Verdruss Jonas, der Gott nun vorhält, er habe das ja gleich gewusst und daher gar nicht erst Prophet sein wollen. Die prophetische Ironie be- steht darin, dass

In this paper, we study the profile of a general class of random search trees that includes many trees used in com- puter science such as the binary search tree and m-ary search

Select your language Films Online Bibles Audio Bibles Many weblinks Calendars.. Bibles Books Booklets

61 The proposal was rejected by most of ASEAN member states for three main reasons. First, the multilateral defense cooperation would send a wrong signal to major powers. It

63 Such educational measures to train the armed forces in civilian skills accelerated the military’s involvement in economic activities that required not only conversion

Noteworthy differences between the mM and IS/7800 keyboards are in the total number of characters that can be generated, the number of Program Function and

Level: Some Possible Indicators. 3 2.3 From Information Channels to Contents,. 7 2.4 Perceived and Unperceived Data Processing. Information Densities as Indicators of