Contents lists available atScienceDirect

Earth and Planetary Science Letters

www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl

Understanding Himalayan erosion and the significance of the Nicobar Fan

Lisa C. McNeill

a,∗, Brandon Dugan

b, Jan Backman

c, Kevin T. Pickering

d,

Hugo F.A. Pouderoux

e, Timothy J. Henstock

a, Katerina E. Petronotis

f, Andrew Carter

g, Farid Chemale Jr.

h, Kitty L. Milliken

i, Steffen Kutterolf

j, Hideki Mukoyoshi

k,

Wenhuang Chen

l, Sarah Kachovich

m, Freya L. Mitchison

n, Sylvain Bourlange

o, Tobias A. Colson

p, Marina C.G. Frederik

q, Gilles Guèrin

r, Mari Hamahashi

s,1, Brian M. House

t, Andre Hüpers

u, Tamara N. Jeppson

v, Abby R. Kenigsberg

w, Mebae Kuranaga

x, Nisha Nair

y, Satoko Owari

z, Yehua Shan

l, Insun Song

aa, Marta E. Torres

ab, Paola Vannucchi

ac, Peter J. Vrolijk

ad, Tao Yang

ae,2, Xixi Zhao

af, Ellen Thomas

agaOceanandEarthScience,NationalOceanographyCentreSouthampton,UniversityofSouthampton,Southampton,S0143ZH,UnitedKingdom bDepartmentofGeophysics,ColoradoSchoolofMines,Golden,CO80401,USA

cDepartmentofGeologicalSciences,StockholmUniversity,SE-10691Stockholm,Sweden dEarthSciences,UniversityCollegeLondon,London,WC1E6BT,UnitedKingdom

eCNRS,UMR6118–GeosciencesRennes,UniversitydeRennesI,CampusdeBeaulieu,35042RennesCedex,France fInternationalOceanDiscoveryProgram,TexasA&MUniversity,1000DiscoveryDrive,CollegeStation,TX77845,USA gDepartmentofEarth&PlanetarySciences,BirkbeckCollege,London,WC1E7HX,UK

hProgramadePós-GraduaçãoemGeologia,UniversidadedoValedoRiodosSinos,93.022-000SãoLeopoldo,RS,Brazil iBureauofEconomicGeology,University Station,BoxX,Austin,TX78713,USA

jGEOMAR,HelmholtzCenterforOceanResearchKiel,Wischhofstr.1-3,Kiel24148,Germany

kDepartmentofGeoscience,ShimaneUniversity,1060Nishikawatsu-cho,Matsue,Shimane690-8504,Japan

lKeyLaboratoryofMarginalSeaGeology,ChineseAcademyofSciences,#511KehuaStreet,TianheDistrict,Guangzhou510640,PRChina mDepartmentofGeographyPlanningandEnvironmentalManagement,Level4,Building35,TheUniversityofQueensland,Brisbane,QLD,Australia nSchoolofEarthandOceanSciences,CardiffUniversity,ParkPlace,Cardiff,CF103XQ,UnitedKingdom

oLaboratoireGeoResources,CNRS-UniversitédeLorraine-CREGU,EcoleNationaleSupérieuredeGéologie,RueduDoyenMarcelRoubault,TSA70605-54518, Vandoeuvre-lès-Nancy,France

pSchoolofEarthSciences,UniversityofWesternAustralia,35StirlingHighway,Crawley6009,Australia

qCenterforRegionalResourcesDevelopmentTechnology(PTPSW-TPSA),AgencyfortheAssessmentandApplicationofTechnology(BPPT),Bldg.820,EarthSystem Technology(Geostech),KawasanPuspitekSerpong,SouthTangerang,Banten,15314,Indonesia

rLamont-DohertyEarthObservatory,ColumbiaUniversity,BoreholeResearchGroup,61Route9W,Palisades,NY10964,USA

sGeophysicsResearchGroup,InstituteofGeologyandGeoinformation,GeologicalSurveyofJapan(AIST),AISTTsukubaCentral7,1-1-1Higashi,TsukubaIbaraki 305-8567,Japan

tScrippsInstitutionofOceanography,UniversityofCalifornia,SanDiego,VaughanHall434,8675DiscoveryWay,LaJolla,CA92037,USA uMARUM-CenterforMarineEnvironmentalSciences,UniversityofBremen,POBox330440,D-28334Bremen,Germany

vDepartmentofGeologyandGeophysics,UniversityofWisconsin-Madison,1215W.DaytonStreet,Madison,WI53706,USA wDepartmentofGeosciences,PennsylvaniaStateUniversity,503DeikeBuilding,UniversityPark,PA16802,USA

xGraduateSchoolofScienceandEngineering,YamaguchiUniversity,1677-1Yoshida,YamaguchiCity753-8512,Japan

yCLCS/MarineGeophysicalDivision,NationalCentreforAntarcticandOceanResearch,EarthSystemScienceOrganization,MinistryofEarthSciences, GovernmentofIndia,HeadlandSada,Vasco-da-Gama,Goa403804,India

zDepartmentofEarthSciences,ChibaUniversity,1-33Yayoi-cho,Inage-ku,ChibaCity263-8522,Japan

aaGeologicEnvironmentalDivision,KoreaInstituteofGeoscience&Mineral(KIGAM),124Gwahak-ro,Yuseong-gu,Daejeon34132,RepublicofKorea abCollegeofEarth,OceanandAtmosphericSciences,OregonStateUniversity,104CEOASAdminBuilding,Corvallis,OR97331-5503,USA

acRoyalHollowayandBedfordNewCollege,RoyalHollowayUniversityofLondon,QueensBuilding,Egham,TW200EX,UnitedKingdom adNewMexicoTech,801LeroyPlace,Socorro,NM87801,USA

aeInstituteofGeophysics,ChinaEarthquakeAdministration,#5MinzuDaxueNanlu,HiadianDistrict,Beijing100081,PRChina afDepartmentofEarthandPlanetarySciences,UniversityofCalifornia,SantaCruz,1156HighStreet,SantaCruz,CA95064,USA agDepartmentofGeologyandGeophysics,YaleUniversity,NewHaven,CT06520-8109,USA

*

Correspondingauthor.E-mailaddress:lcmn@noc.soton.ac.uk(L.C. McNeill).

1 Nowat:EarthObservatoryofSingapore(EOS),NanyangTechnologicalUniversity,50NanyangAvenue,Singapore639798.

2 Nowat:InstituteofGeophysicsandGeomatics,ChinaUniversityofGeosciences,388LumoRoad,Wuhan430074,PRChina.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2017.07.019

0012-821X/©2017TheAuthor(s).PublishedbyElsevierB.V.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBYlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t ra c t

Articlehistory:

Received3February2017 Receivedinrevisedform7July2017 Accepted10July2017

Availableonline10August2017 Editor:M.Bickle

Keywords:

Bengal–NicobarFan submarinefan Himalayantectonics Asianmonsoon IndianOcean

AholisticviewoftheBengal–NicobarFansystemrequiressamplingthefull sedimentarysectionofthe NicobarFan, whichwas achievedfor thefirst timeby InternationalOceanDiscoveryProgram (IODP) Expedition362westofNorthSumatra.Weidentifiedadistinctriseinsedimentaccumulationrate(SAR) beginning∼9.5Maandreaching250–350m/Myr inthe9.5–2 Mainterval,whichequalorfar exceed ratesontheBengalFanatsimilarlatitudes.ThismarkedriseinSARandaconstantHimalayan-derived provenance necessitates amajor restructuring ofsediment routing in the Bengal–Nicobar submarine fan. Thiscoincides with the inversion of the Eastern Himalayan Shillong Plateau and encroachment of the west-propagating Indo–Burmese wedge, whichreduced continental accommodation spaceand increasedsedimentsupplydirectlytothefan.Ourresultschallengeacommonlyheldviewthatchanges insedimentfluxseenintheBengal–Nicobarsubmarinefanwerecausedbydiscretetectonicorclimatic eventsactingontheHimalayan–TibetanPlateau.Instead,aninterplayoftectonicandclimaticprocesses causedthefansystemtodevelopbypunctuatedchangesratherthangradualprogradation.

©2017TheAuthor(s).PublishedbyElsevierB.V.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBYlicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Introduction

TheBengal–NicobarFan,IndianOcean(Fig. 1),hasthegreatest areaandlengthofanysubmarinefan,andhaslongbeenstudied toinvestigatepossiblelinksbetweenHimalayantectonicsandthe Asianmonsoon (e.g.,An etal., 2001; Bowles etal., 1978; Clift et al.,2008; Curray,2014; CurrayandMoore,1974;France-Lanordet al.,2016; SchwenkandSpiess,2009; Mooreetal.,1974).Todate, a holistic synthesis of the Indian Ocean fan system history and relatedprocessesoftectonics,climateanderosionhasbeenham- peredbya lackof datafromtheNicobar Fan.The importanceof samplingwidelyacross asedimentarysystemtoavoidbiasesdue tomajortemporalchangesinchannelandlobeactivitywasnoted (Stowetal., 1990), andhighlighted thattheunder-sampledNico- barFan may hold a key componentof the eastern Indian Ocean sedimentationrecord.

InternationalOcean Discovery Program(IODP) Expedition362 sampled and logged the Nicobar Fan offshore North Sumatra in 2016(Fig. 1).Thestratigraphicresultsfromthisexpedition(Dugan etal.,2017) areintegratedherewithresultsfromprevioussiteson the Bengal–NicobarFan and NinetyeastRidge (NER) of the Deep Sea Drilling Program (DSDP Leg 22, von der Borch et al., 1974), Ocean Drilling Program (ODP Leg 116, Cochran et al., 1989; Leg 121,Peirceetal.,1989)andIODP(Expedition353,Clemensetal., 2016;Expedition354,France-Lanordetal.,2016).Wepresentthe firststratigraphicdata fromthe NicobarFan andreappraisepub- lishedchronostratigraphicdatafromBengalFanandNERdrillsites intoa unifiedmodern timescale tofacilitateaccurate comparison ofdepositional recordsacross thewhole system. Comparingsed- imentaccumulation rates(SARs)betweenthesesitesgivesanew andintegrativeunderstandingofthetimingoffangrowthanddis- tributionoffandeposits.

2. NicobarFanstratigraphyandsedimentsource

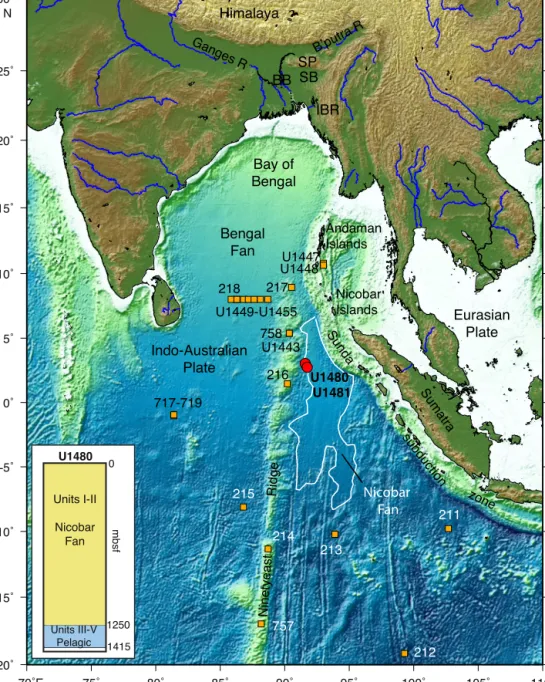

Expedition362 drilled two sites onthe northern Nicobar Fan eastofthe NER(Fig. 1),samplingthe completesedimentary sec- tionatSiteU1480toabasementdepthof1415 m belowseafloor (mbsf), and from 1150 mbsf to within 10s m of basement at Site U1481 at 1500 mbsf. At both sites Units I and II represent the Nicobar Fan, with Units III–V representing intervals domi- nated by pelagic sedimentation with significantly reduced SARs (Fig. 1).

Bengal Fan sediments are predominantly micaceous quartzo- feldspathicsands of the Ganges andBrahmaputra that drain the HimalayaandsouthernTibetplus contributionsfromtheMeghna

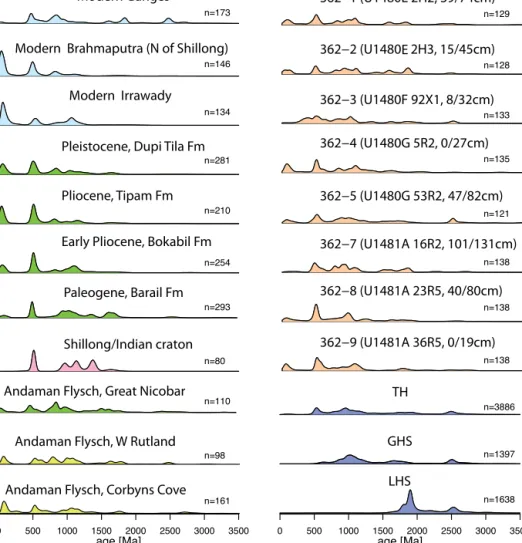

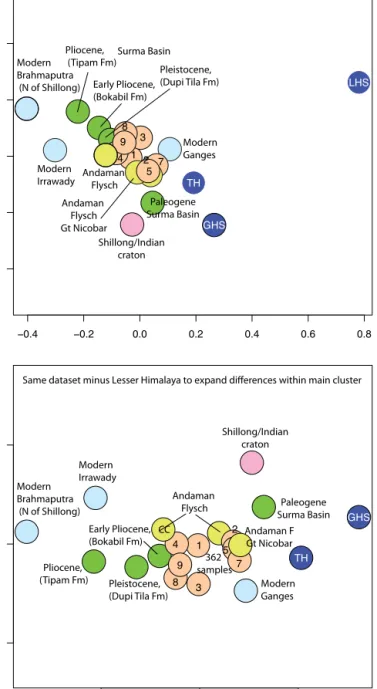

riverthatdrainsnortheasternIndiaandBangladesh(France-Lanord et al., 2016). Despite proximity to the Sunda forearc, the Nico- bar Fan sediments at Sites U1480 and U1481 (Fig. S1) contain a similar range of siliciclastic sediment gravity-flow (SGF) de- posits(mostly turbidites)asBengal Fansites.The sand- and silt- size grain assemblage in the Nicobar Fan is relatively uniform downholeasquartzo-feldspathic(arkosic)sands,withpeliticmeta- morphic lithic grains, mica, minor detrital carbonate (<5%), mi- nor woody debris, and an abundant and diverse assemblage of mostly high-grade metamorphic heavy minerals (including kyan- ite and sillimanite). Candidate sources for the Nicobar Fan in- clude the Himalayan-derived Ganges–Brahmaputra, Indo–Burman Ranges/WestBurma, Sundaforearc andarc, andNER.Detritalzir- con age spectra of samples from the Nicobar Fan sand-silt SGF deposits are dominantly sourced from the Greater and Tethyan HimalayamixedwithsedimentfromtheBurmesearc-derivedPa- leogene Indo–BurmanRanges, similar to the provenance of Neo- gene sands deposited in the eastern Bengal and Surma basins (Najman et al., 2008, 2012) (Figs. 1–3). The limited arc-derived ash content in sedimentsat Sites U1480–1481 suggeststhat the Sunda forearc makes only a minor contribution. Significant in- put from the Irrawaddy drainage is unlikely as it would require transfer of material across the forearc and possibly the trench.

Cenozoic sediment isopachs of the Martaban back arcbasin, the main north–south-oriented depocentre in the Andaman Sea re- latedtothedevelopmentoftheThanlwin–Irrawaddydeltasystem, show no obvious evidence for major routing to the west where carbonate-capped volcanic highs (e.g. Yadana High) served as a barrier for most of the Neogene (Racey and Ridd, 2015). Never- thelessweconsiderIrrawaddysourcesinourprovenanceinterpre- tations.

3. Bengal–NicobarFansedimentaccumulationpatterns

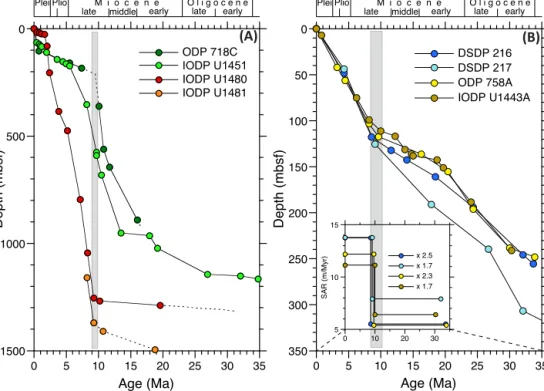

Age-depth distributions of calcareous nannofossils, planktonic foraminifers, diatoms,silicoflagellates, andradiolarians wereused to create tie points for SARs forExpedition 362 sites (Dugan et al., 2017) (Fig. 4A; Supplementary Material). Also, published lat- estEocene-Recentbiomagnetostratigraphicdatafromsixrepresen- tative DSDP, ODP and IODP Bengal Fan and NER sites were re- assessedandplacedonacommontimescale(Hilgenetal., 2012;

Pälikeetal., 2006) (Fig. 4;Supplementary Material).Thereassess- mentofpreviousbiostratigraphicdataandthechoiceofagemodel tie points considered recent developments in understanding the consistencyandreliabilityofbiohorizonsinlowerlatitudeenviron- ments.Atallsites,theage-depthrelationshipisnon-linear.AtSites U1480andU1481ontheNicobarFan,theSAR increasesdramati-

Fig. 1.Regionalmapofstudyarea.MapincludesBengal–NicobarFansystem,riversystems,easternHimalayanprovinces,andrelevantDSDP/ODP/IODPsites.BB=Bengal Basin;SP=ShillongPlateau;SB=SurmaBasin;IBR=Indo–BurmanRanges.InsetsummarizesSiteU1480lithostratigraphy.

callyat9.5–9Ma,from<15m/Myrto>200m/Myr,whichcorre- spondstotheonset ofsignificantfan depositionattheUnitIII–II boundary. Specifically, atSite U1480 ratesincrease from 2–15to 223m/Myr,andatSite U1481from11–27to207m/Myr(Figs. 4, S2).AtSiteU1480,highratespersistandintheearliestPleistocene (∼2–2.5Ma),theyincrease furtherto360 m/Myr(Fig.S2).Inthe Bengal Fan, such high rates, of the order of 250–300 m/Myr or greater, are only found within the more proximal fan (e.g., We- ber etal., 1997,although greater spatial andtemporal variability inrates might be expectedhere dueto highimpact of sealevel fluctuationcoupledwithshiftingchannel/levée systems)orinthe latestPleistocene(e.g.,Expedition354resultsofFrance-Lanordet al., 2016). These results emphasize the significance of the Nico- barFanwithinthewiderBengal–NicobarFansystemfromthelate MiocenetoearlyPleistocene(∼9–2Ma).

The NER (separating the Bengal and Nicobar fans) is thought to capture an elevated expression of fan deposition despite its predominantlypelagiccomposition(Peirceetal.,1989),duetoin-

creased flow lofting (cf., Stow et al., 1990) and nepheloid layer flux.Remarkably,atallnorthernNERsites(216,217and758/1443;

Fig. 2B)SARsincreasebyafactorof2–3at∼10–8Ma,coevalwith theNicobarFansiteincreases.Decreasingcarbonatecontentvalues atSites217, 758,1443,support thattheincrease inSAR resulted fromtheeffectofincreasedinputofclay.

When SARs increase on theNicobar Fan andNER (at 2–9◦N), ratesontheBengalFanatrelatedmid-fanpositions(Fig. 4A)show eitheramarkeddecrease(e.g.,Site718,at1◦S)orminimalchange (e.g.,Site1451, at8◦N),andallratesare lowerthanontheNico- bar Fan immediately after 9–9.5 Ma. At Site 718, rates decrease from275to12–13m/Myrat9.5Ma andonlyexceed100m/Myr inthelatePleistocene(Fig.S2).AtSite1451,ratesfrom9.5Mado notexceed150m/Myr(range:70–150m/Myr;Fig.S4).Localvari- ationsindeposition betweenLeg116sites(717,718,719)canbe explained bylate Miocenefolding ontheIndian platecontrolling accommodationandpotentialsubmarine-channelrouting(Stowet al.,1990).

Fig. 2.Detritalzirconageplotsforsamplesandequivalentplotsofregionalriversandformations.TH=TethyanHimalaya;GHS=GreaterHimalayaSeries;LHS=Lesser HimalayaSeries.DetailsofExpedition362samplesaregiveninTableS1.

Depositional history at a single site is inevitably affected by individual channel and lobe positions and there will be vari- ability across the fan in terms of sediment accumulation due to depositional environment, e.g., channel-axis, channel-margin, levee-overbank,lobe andlobe fringe etc. (e.g.,Stow et al., 1990;

Schwenk and Spiess, 2009). However, on the Nicobar Fan seis- mic horizons and packages can be traced over large distances with confidence in unit correlation and with minimal evidence ofunitthicknessvariation acrossandalongtheoceanicplate. No onlap in the vicinity of the drillsites is observed, and channel- levée complexes that might correlate with enhanced deposi- tion are evenly distributed spatially and temporally (Dugan et al., 2017). In addition, our analysis of data from other Expedi- tion 354 Bengal Fan transect sites where SARs may be greater thanat Site U1451 (e.g., U1450,France-Lanord etal., 2016) con- tinues to support that during the late Miocene and Pliocene, Nicobar Fan rates either exceeded or were broadly compara- ble with those on the Bengal Fan. This interpretation is fur- ther supported because the Expedition 354 sites on the Ben- gal Fan are located 5◦N of the Expedition 362 sites on the Nicobar Fan (and therefore probably in a more proximal posi- tion).

PreliminarybenthicforaminiferaldatafromtheSiteU1480pre- fan and lowermost Nicobar Fan deposits indicate that this part ofthe Indian platewas at upper abyssaldepths (2500–3000 m;

SupplementaryMaterial),not isolatedatahigherelevationwhich

could delay arrival of fan sediments. Combining these facts, we haveconfidencethatthe drillsitestratigraphicrecordisrepresen- tativeofthewiderNicobarFan.

Compilation ofage-depth plots and SARsfrom across the fan system enables us to examine earlier sedimentation patterns.

These indicate that by at least 15 Ma, SARs on the Bengal Fan were high with sediment directed west of the NER (Fig. 5C).

The oldest recovered sediments in the central part of the Ben- gal Fan are Oligocene (25–28 Ma) thin-bedded silts, and the first significant sands are late Miocene, although this may be related to changes in coring technique and recovery (9–10 Ma:

Site U1451, France-Lanord et al., 2016). At other Expedition 354 sites, the apparent earliest onset of substantial sand was <8 Ma (Sites U1450 and U1455), although we note that low re- covery in parts of the deeper section at these sites may al- low for the presence of additional earlier thick sand layers. In the distal Bengal Fan (Leg 116 Sites 717–719), early Miocene (back to 17 Ma) silts came from the Himalaya and minor com- ponents from the Indian subcontinent (Cochran et al., 1989;

Bouqillonetal., 1990;Copelandetal., 1990). AtNicobar FanSite U1481,a20-mintervalwithintheperiod19–9Ma(sample362–9 inFigs. 2 and3) includesminorveryfine-grainedsandstonesand siltstones, with the same zircon assemblage as other Expedition 362 sand/silt samples (Fig. 2), supporting an eastern Himalayan source. These predate the dramatic increase in sediment flux to theNicobarFansites.

Fig. 3.Detritalzirconagecomparisonplotsofsamplesfromthisstudyandregional riversandformations.Multidimensionalscalingmaps(Vermeesch,2013)basedon calculatedK–SdistancesbetweenU–Pbagespectra,comparingNicobarFansand samplesfrom thisstudywithpossiblesourceareascompiledfromtheliterature (Allenetal.,2008;Braccialietal.,2015, 2016;Campbelletal.,2005; Gehrelsetal., 2011; Limontaetal.,2017; Najmanetal.,2008).Themapsshow362samplesshare thesamesourcesastheSGFdepositsexposedontheAndaman–NicobarIslandsand NeogenesedimentsdepositedinnortheastBengalthatwereoriginallysourcedfrom erosionoftheIndo–BurmaRanges.TheIODPsandsarenotdirectlycomparableto sandsfromthemodernBrahmaputraorIrrawaddy.SeeFig. 2foracronyms.

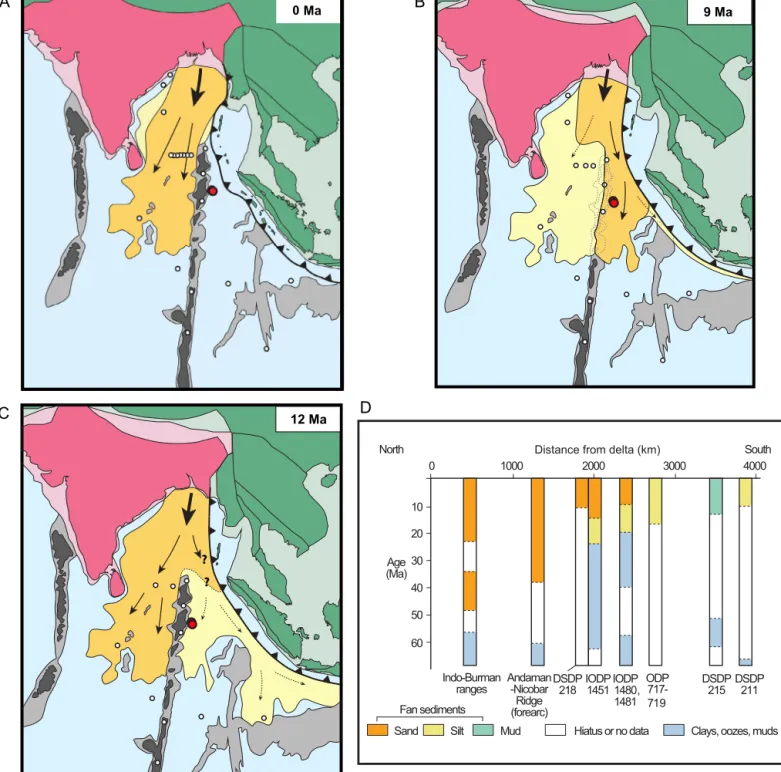

Insummary,although theBengal–Nicobar Fanwas clearly de- veloping prior to the late Miocene, the SARs at a rangeof sites support a marked increase in sediment flux at around 9.5 Ma, in particular to the eastern part of the system, the Nicobar Fan (Fig. 5B; an idea postulated by Bowels et al. (1978), confirmed herewithdetailedandintegrateddrillingandseismicdata).Ama- jorconclusionfromourappraisalofSARsisthatwhenhighSARs arerecordedontheBengalFan,theyaresignificantlyloweronthe NicobarFan,andthat between∼9.5–2 Mathisswitches abruptly (Fig. 3),withhighestsedimentfluxdeflectedtotheeast.

4. NicobarFanvolumetricsandlateMiocene–recentgrowthof theSundaforearc

Using sediment thickness from seismic profiles and ocean drilling boreholes, we have made a new estimate of the late Miocene–RecentNicobarFanvolume,incorporatingthecomponent of fannow accreted intothe Sundasubduction margin (see Sup- plementary Material). Estimates of the present day Nicobar Fan volumeare∼0.5×106km3(Figs. 1,S4;SupplementaryMaterial), withoutdecompaction.Anadditional0.4× 106 km3 isestimated tohavebeenaddedtotheaccretionaryprismbetweentheNicobar Islands andSouthern Sumatra, usingpresentdaysediment thick- nesses and plate convergence rates back to 9 Ma (Fig. S5). This generates aminimum lateMiocene–Recent (i.e.from∼9.5Ma to present) Nicobar Fan volume of ∼1 × 106 km3. This volume is significantcomparedwiththeestimatedBengalFanvolumeof7.2

× 106 km3 for the entire Neogene, a period of ∼20 Myr (Clift, 2002).

The increase inthicknessoftheIndian platesedimentsection at ∼9.5 Ma would have corresponded to a marked and abrupt changeinsediment volumeinputtothenorthSundamargin.Off- shore North Sumatra and the Nicobar Islands, the forearc prism is markedly wide (150–180km) and thick relative to therest of the margin and to other accretionary prisms (McNeill andHen- stock, 2014),andthenorthern Sumatranprism formsan unusual plateau inferred to be a consequence of internal and basal ma- terial properties and/or prism growth history (e.g., Fisher et al., 2007).Thelargeadditionalsedimentinputvolumefrom9.5Mato present in the easternmost Indian Ocean is a significant propor- tion of theprism volume andcan explain the anomalously large northernSundaprism(supportinghypothesesby Hamilton,1973;

Karigetal.,1979).

5. Discussion

OurnewintegratedNicobar–BengalFansedimentrecordsshow a net increase in flux to the eastern Indian Ocean at 9.5–9 Ma, representing the onset of a newsedimentary regime in the east Indian Ocean.Detritalzirconages(Fig. 2)andpetrologyfromthe Nicobar Fan sedimentsshow the sand provenance remainedun- changed throughoutthe middleMiocene topresent. To constrain sources wecompared theseresultswithdetrital zirconagesfrom potential sourceregions intheHimalayasaswell astheBurmese arcandIrrawadydrainageduetothepresenceofCenozoicagezir- cons (mainly between 60–20Ma). Comparison of the zircon age distributions(Fig. 3)showSGFdepositsexposedontheAndaman–

Nicobar Islands are closelysimilar to Nicobar Fan sedimentsand that bothhaveaffinitieswithHimalayan-derivedunits,theTrans- Himalayaandarc-derivedinputfromerosionoftheIndo–Burman RangesthatwereexpandingwestwardsduringthePliocene.These are the same sources asNeogene sands deposited in the north- east Bengal and Surma basins via the paleo-Brahmaputra River (Najman et al., 2012) (Fig. 1). Between 15–9 Ma the northeast Bengal Basin underwent inversion related to tectonic shortening and exhumation of the Shillong Basin Plateau which accommo- dates up to 1/3 ofthe present-day convergence across theEast- ern Himalaya (Bilham and England, 2001; Biswas et al., 2007;

Clark andBilham, 2008) (Fig. 1). Exhumation and erosionof the Himalayan-derived SurmaGroup atop the Shillong Plateau began atthistimefollowedbythemainphaseofsurfaceuplift<3.5 Ma (Najmanetal.,2016) –thesetimingsprovideanexcellentfitwith the highSARs on theNicobar Fan (from 9.5, and2.5–2 Ma). We propose that this inversion of the Shillong region and westward migration of the Indo–Burmese wedge reduced accommodation and diverted sediments south to the shelf andNicobar Fan. The mostsignificant sediment pulseto the NicobarFan,at 2.5–2 Ma,

Fig. 4.Age-depthrelationshipsatoceandrillingsites.Panel(A)showstiepointsofbiomagnetostratigraphicage-depthrelationshipsforBengalFansites(718C,U1451)and NicobarFansites(U1480,U1481).Panel(B)showsbiomagnetostratigraphictiepointsofage-depthrelationshipsforsitesfromtheNinetyeastRidgecrest(216,217,758A, 1443A).Insetshowssedimentaccumulationrate(SAR)increasebetween9and10Ma.DataarepresentedindetailinFigs. S2andS3,andTablesS2andS3.

mayalsorecord erosion ofthe exhumedeastern Himalayan syn- taxisandresultingerosion,withatleast12kmofmaterial since 3 Ma – a signal recorded in the Surma Basin from the latest Pliocene (Bracciali et al., 2016) but not previously identified in theIndian Ocean. From ∼2 Ma, a SAR reduction on the Nicobar Fansupportsthehypothesis thatimpingement oftheNERonthe SundaTrenchdivertedtheprimaryfluxwestoftheridgewithcon- comitant highmid-late Pleistocene SARs on the BengalFan (e.g., France-Lanordetal.,2016)(Fig. 5A),althoughwestwardre-routing oftheBrahmaputraRiver mayalsohaveplayedarole (Najmanet al.,2016).

TheNicobarFanisvolumetricallysignificantwithintheBengal–

NicobarFansystem,andatcertaintimesduringthelateMiocene–

earlyPleistocene,suchasthenear400m/MyrSARsoftheearliest Pleistocene, it may have been a dominant sediment sink. Since 10 Ma,sealevelhasgenerallyfallen(Milleretal., 2005),decreas- ing accommodation on the shelf, thus amplifying the processes drivingsedimentsouthwardtothefan.Erosionwasprobablyaided bySouthAsianmonsoonstrengtheninginthemidtolateMiocene (e.g., An et al., 2001; Betzler et al., 2016; Kroon et al., 1991;

PetersonandBackman,1990; PrellandKutzbach,1992)combined withtheorographicforcingthatcausedthelocusofmonsoonpre- cipitationto shiftsouth onto the newly uplifted Shillong Plateau (Biswasetal., 2007). Enhancederosion rates(Duvall etal., 2012) and/orupliftintheeasternTibetanplateau(e.g.,Anetal.,2001)in thelateMiocenewouldalsocontributetothevolumeofsediment available.

Avulsionoflarge-scale channel-levéecomplexes iscommonto manysubmarine fans (e.g., Amazon Fan; Flood etal., 1991). We propose that the eastward deflection of sediment towards the NicobarFan at9.5 Ma was the resultof channel avulsion in re- sponse to increased sediment flux. Consequently, the proportion of sediment routed from the northeastern Bengal Basin to the BengalFanwas significantlyreduced. Any differentialseafloorto- pographyontheshelf andthesubsidingNERcouldhaveassisted thiseastward diversion process. Similar processes have beenob-

servedinphysicalflumeexperiments,forexample,lobeswitching observed withchange insedimentation supply/rate, accommoda- tion,anddepositionalslope(Fernandezetal.,2014; Parsonsetal., 2002).

An early, lower-volume phase of fan deposition is recorded in the accreted sediments ofthe Sunda forearc (to ∼40–50 Ma;

Curray andMoore,1974; Curray etal., 1979; Karig et al., 1980).

A modeloftrench-axialsupply,withsedimentnowalmostentirely accreted,canexplainthisearlierphase(nascentNicobarFan),with trenchoverspilldeliveringminorsands/siltsrecordedatSiteU1481 bythemiddleMiocene.

An accurate history of siliciclastic deposition on the Bengal–

Nicobar Fan system necessitates knowledge of both fans. Using estimates of fan volume, we demonstrate that the Nicobar Fan is significant within the overall sediment budget of the Bengal–

NicobarFan,particularlyfrom9.5–2Ma.Thispreviouslyunquanti- fiedsedimentsinklikelyalsocontributestoorganiccarbonburial budgets (cf. Galy et al., 2007). An interplay of tectonic, climatic andsedimentologicalprocesses,ratherthan adiscrete tectonicor climaticeventormechanismsuchasmonsoononset,asoftenin- voked(e.g.,Betzleretal.,2016;Cliftetal.,2008),movedsediment throughaseriesofstagingareasandcontrolledSARsinthevarious sediment sinksoftheIndo–Asiansystem.Ourreappraisalofinte- grateddrilledfandataisinconsistentwiththelong-heldnotionof gradualfanprogradation(Currayetal.,2003) butrathersuggestsa moredynamicsystemofpunctuatedandabruptchanges(Fig. 5D).

Ourworkhighlightstheimportanceofsediment routingfromthe uplifting EasternHimalaya alongthe eastern IndianOcean tothe NicobarFanduringthelateNeogene,aregionwhoserolehasbeen significantlyunderappreciated.

Acknowledgements

Thisresearch used samplesanddataprovided bythe Interna- tionalOceanDiscoveryProgram(IODP)(www.iodp.org/access-data- and-samples).TheJOIDESResolutioncrewandIODPtechnicalteam

Fig. 5.ConceptualmodelofBengal–NicobarFansystemhistory(tectonicsfromHall (2012);fanmorphologyfromBowlesetal. (1978)andCurray (2014);fandatafrom DSDP/ODP/IODPsites(whitedots;reddots=Expedition362sites).A)LatePleistocenetoRecent,sedimentationprimarilyonBengalFan,B)lateMiocene–Pliocene,Nicobar Fandominates,C)pre-lateMiocene,BengalFandominates,minortrench-axialsupplytoSundamargin/NicobarFan.D)PatternofsedimentationalongtheBengalFansystem fromproximal(left)todistal(right)indicatingabsenceofsimplefanprogradationalpattern(updatedfromCurrayetal.,2003).Datasources:Indo–BurmanRangesand Andaman–Nicobarforearcdata(BandopadhyayandGhosh,2015; Currayetal.,2003andreferencestherein);oceandrillingsitedata(Cochranetal.,1989, 1990;France-Lanord etal.,2016; von derBorchetal.,1974;thisstudy).Allsitesconvertedtomoderntimescale(SupplementaryMaterial).Notethat9.5–18MasiltsforNicobarFansitesare onlypresentatSiteU1481.

are thanked for their contributions during Expedition 362. We thankthe editor andtwo reviewers fortheir valuable comments whichhelpedtoimprovethepaper.McNeillacknowledgessupport duringandfollowingtheExpeditionfromNaturalEnvironmentRe- searchCouncilgrantNE/P012817/1.

Appendix A. Supplementarymaterial

Supplementarymaterialrelatedtothisarticlecanbefoundon- lineathttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2017.07.019.