Language: Genre effects on the usage of SELF Erin Wilkinson

1. Introduction

This study broadly inquires whether there is morphosyntactic variation in American Sign Language (ASL) driven by sociolinguistic factors, investi- gating the usage of SELF in ASL in Canada and the United States. The data for this study is drawn from 32 hours of naturalistic ASL discourse. Under- taking a usage-based analysis on a grammatical morpheme provides crucial insights about morphosyntactic variation within a language. A grammatical morpheme, by tradition, is not highly variable compared to phonological and lexical variation. Although there is preliminary evidence of morphosyntactic variation across signed languages, there is not much known about morpho- syntactic variation within a signed language (Zeshan 2004). This study aims to provide insights about morphosyntactic variation within ASL.

The goal of this study is to empirically investigate the distribution of a grammatical set of three SELF forms in two variations of ASL. The main question of the study asks whether Canadian and American signers produce SELF similarly or differently. If differences are found, which factors appear to drive differences in the usage of SELF? This can be examined by observing patterns within a variety of genres. Due to the nature of the data- driven investigation, findings will be reported on with quantitative outputs.

The ASL corpus of Canadian and American variation includes a variety of genres: narratives, monologues, and 2-person conversations. Are there factors that contribute to differences in the usage of SELF other than regional variation such as genre? Do we see token and type frequency to be consist- ently produced across three genre types in Canadian and American varia- tions of ASL? If we find asymmetry in frequency distribution in SELF usage, then this study will put forward the idea that genre types may be a driving factor in language variation in signed languages. The study will highlight the distribution of SELF by region and genre within and across Canadian and American variations.

Findings report differences in the distribution of SELF across both corpora of Canadian and American variations. Initial findings suggest that the usage of SELF is driven at least by two social factors of region and genre, indicating an emerging evidence of morphosyntactic variation in ASL.

This paper is divided into seven sections which provide descriptive and quantitative data. The first section provides an overview of language varia- tion in signed language. The following section covers the breadth of sociolin- guistic variation of –self pronouns in spoken languages. Third, this paper will summarize the formal and grammatical properties of three SELF pronouns in ASL and review the general discussion of previous work. I then describe the methodology of building the language corpus along with a brief discus- sion about genre sampling. The procedure of data coding will be described followed by data analyses and findings on the cross-variation distribution of SELF usage by factors of region and genre. The paper will end with a discus- sion of implications of morphosyntactic variation in ASL and how these find- ings may apply generally to other signed languages.

2. A brief overview of morphosyntactic variation in signed languages Discussion about language variation in signed languages continues to be meager; however, most sociolinguistic studies have revolved around phono- logical and lexical variation in signed languages. Morphosyntactic variation in signed languages remains to be poorly investigated, thus underdescribed.

Since there is a close relationship between properties in a word and its syntactic expression, it is challenging to categorically assign specific aspects by either morphological or syntactic properties. Instead of differentiating between morphological and syntactic properties, they are better described as morphosyntactic properties (Croft 2001).

There were only four studies that directly examined morphosyntactic variation in signed languages. One study reported lexicogrammatical vari- ation of negative and interrogative forms in Flemish Sign Language (Van Herreweghe and Vermeerbergen 2006).1 The other three analyses examined variable subject expressions in American, Australian, and New Zealand Sign Languages (Wulf et al. 2002; McKee et al. 2011; Schembri and Johnston 2006). Lucas, Bayley, and Valli (2001) was the first known study to identify variability in subject expressions in ASL. They analyzed subject pronominal expressions that contrasted with the presence and absence of an overt subject pronoun in a predicate construction. A signer may choose to realize the subject pronoun with an overt form in the construction of [PRO.1 THINK]

or without the pronominal form as shown in [ Ø THINK] (Lucas, Bayley, and Valli 2001: 159). Another ASL study by Wulf et al. (2002) found that verb types predict how the subject pronoun would be realized. While inflecting verb signs require subject pronouns to be overt, there is no obligatory expres- sion of subject pronoun with non-inflecting verbs known as plain verbs (cf.

Padden (1988) for further description of verb types). More broadly, subject nominal expressions may either be present or absent in the signed utterance, prompting researchers to question possible factors that influence variability in subject expression in these respective signed languages. Moreover, the phenomenon of variable subject expression is also observed in numerous spoken languages like Spanish (Travis 2007).

Wulf et al. (2002) argued that the variable deletion of subject expression may serve as morphosyntactic variation in ASL. They found age and gender to be significant social factors in their American study. Younger signers and men favored null expressions of subject nominals whereas older signers in the age bracket of 55 and over and women preferred overt subject noun phrases. In contrast, Schembri and Johnston (2006) found that gender and age of the signer played no significant role in variable subject pronominal expressions in Australian Sign Language. McKee et al. (2011) conducted a corpus-based study on variable subject expression in Australian and New Zealand Sign Language. Results yielded no effects of age and gender in both signed languages, parallel to findings from the Australian study by Schembri and Johnston (2007).

However, McKee et al. found that ethnicity played a minor role that affected differences in subject expressions between indigenous and white signers in New Zealand Sign Language. Maori signers often expressed subject noun phrases but this was not seen in white signers (McKee et al.

2011). This finding is reminiscent of the study on African-American signers who favored overt subject expressions compared to white American signers (Lucas, Bayley, and Valli 2001). As for linguistic factors, the genre effect was partially observed in variable subject expression where signers produced more overt subject noun phrases during interviews compared to conversa- tions (McKee et al. 2011). Although there is no consensus regarding socio- linguistic trends found in these three languages, these studies concurred that variable deletion of subjects is observed in signed language discourse.

Other than the four studies on variable subject expression, negation, and interrogation, there is no known sociolinguistic analysis on morphosyntactic variation in signed languages to date. To exemplify the impoverishment of morphosyntactic variational work in signed languages, a large-scaled socio- linguistic publication indicated no known studies on syntactic variation on

British, Australian, and New Zealand Sign Language (BANZSL) (Schembri et al. 2010). However, many papers have identified influences of surrounding spoken languages on signed languages through adopting specific syntactic features like word order, fingerspelling, and specific lexical signs (Lucas and Bayley 2011; Schembri et al. 2010). There remains extensive amount of work ahead of us to understand more about social and linguistic factors that shape morphosyntactic variation in signed languages. Since this study is about a special set of pronouns in ASL, results of the study will contribute partially to our understanding of morphosyntactic variation in a signed language.

The following section introduces sociolinguistic variation of –self pronouns in spoken languages.

3. –self pronouns in English: Variation in form and function

The set of –self forms (e.g. myself, themselves) in English has been tradition- ally defined as a reflexive pronoun. The function of a reflexive is to mark co-referentiality of the same participant in an event. But other works have argued that –self pronouns also function as an intensifier and/or emphatic (e.g. Kemmer and Barlow 1996; König and Siemund 2000). Kemmer and Barlow (1996) conducted a discourse-based analysis of English –self forms.

They found that the function of –self was not limited to a reflexive pronoun but can be extended to function as an emphatic marker. Their distributional analysis revealed that English speakers often juxtaposed the emphatic form to the headed noun phrase (in the subject position) in the utterance. The func- tion of the –self form adjuncted to the headed noun phrase was to explic- itly disambiguate the target referent from other potential referents within a discourse context. Therefore –self forms serve as linguistic devices to keep track of discourse referents, as a conversation may include more than one referent. Also, the use of emphatic –self is motivated by signaling some degree of unexpected elements in the discourse event. As a result, there are two types of functions in English –self pronouns (Kemmer 1995; Kemmer 2003; Kemmer and Barlow 1996).

In terms of sociolinguistic variation of reflexive pronouns in spoken languages, dialectal variation of reflexive pronouns in English has been well described (Wagner 2008; Trudgill 2002). Standard English reflexives are formed by a construction of either possessive pronoun or object personal pronoun with –self/-selves, demonstrating an irregular system of reflexives.

In contrast, most non-standard English variations underwent regularization

in their reflexive system, presenting a paradigm where all reflexives are formed by a [possessive pronoun + –self/-selves] (Trudgill 2002). Further- more, some English variations do not mark plural on reflexive pronouns although the plural is clearly marked on the possessive pronoun in the first component of the reflexive form (Wagner 2008). Two nonstandard English varieties, i.e., West County English (southwest of England) and Appalachian English have been well defined in terms of their system of reflexive forms that differed from the standard English variety. Furthermore, the discussion also involved differences in the syntactic distribution of reflexive and non- reflexive pronouns (e.g. herself vs. her) in standard and non-standard vari- ations of English (Trousdale 2011). While sociolinguistic factors were not clearly specified, it appears that the geographical region partially contributed to language variation of the reflexive system.

One may consider other social and linguistic factors that may contribute to the sociolinguistic variation of –self pronouns. Given the differences in formal and functional properties of –self pronouns in English, one may wonder about possible sociolinguistic factors; however, this has not been investigated to date.

4. A brief overview of SELF: Interaction of phonology and grammar This section provides a general characterization of SELF in ASL along with descriptions of formal and grammatical properties of SELF. This discussion draws on two earlier studies of SELF (Wilkinson 2008, 2012), and other studies on SELF will also be reviewed.

Studies have conventionally described SELF as a reflexive pronoun that expresses co-referentiality of the target referent (Baker-Shenk and Cokely 1980; Kegl 2003; Liddell 2003; Lillo-Martin 1995, 2003). In an event construction that involves two participants, the verb is clearly transitive to demonstrate an actor doing something to someone. However, in some cases, both participants happen to be the same referent, so that reflexive pronouns are then employed to mark co-referentiality.

An example (1) of SELF as a reflexive is provided below:

1) LAST-WEEK TWO DEAF PERSON KILL SELF++

3SG

‘Last week, two deaf people killed themselves’ (Ridor9th, 5-17-10 Tidbits, 9:17m)

In this example (1) a vlogger2 informed his viewers that two suicides took place the week before he made this vlog. Since KILL is a transitive verb that requires two semantic and syntactic roles (agent/subject; patient/object) to be fulfilled in ASL, the vlogger had to produce SELF++ in the object posi- tion to inform the viewer that the act of killing involved the same participant who did the act and experienced the action of killing. Suppose the vlogger did not realize the SELF form following the KILL sign, then it appears to be better described as passivization since the focus of the utterance would have highlighted the fact that both deaf people were killed and/or do not know who was the killer.3

Contrary to traditional descriptions of SELF in ASL, recent works suggested that SELF is not best described as a reflexive pronoun but instead an emphatic marker (Koulidobrova 2009; Wilkinson 2008).4 Specifically, Koulidobrova (2009) argued that SELF functions as an adnominal intensi- fier, employing the pronoun to emphasize the nominal referent. Wilkinson (2008) conducted a usage-based study on three SELF forms, replicating the methodology and analysis used in the English –self study by Kemmer and Barlow (1996). The study found that most examples of SELF involved emphatic use based on 15 hours of data. Data reported that 81.7% of SELF pronouns emphatically marked the target referent in ASL discourse, and were frequently realized in the subject position of the utterance. The second most frequent function was a reflexive, found in 13.7% of the data. The remaining 4.6% of the data revealed the third function, a formulaic sequence, where SELF and another lexical sign are fused together in a fixed expres- sion. Wilkinson proposed that SELF is best described as a discourse-based emphatic use, which parallels the emphatic uses of English –self pronouns in the study conducted by Kemmer and Barlow (1996).

The study proposed that the emphatic SELF serves to disambiguate the target referent from other potential referents in discourse context.

Below an example (2) of SELF as an emphatic in ASL is shown.

(2) #EVA #BRAUN SELF-ONE++ PREGNANT

3.sg-focus-marked

‘Eva Braun is pregnant’ (Chalb, 13:37m)

The extracted utterance demonstrated how the signer employed an emphatic SELF to disambiguate the target referent, Eva Braun, as the conversation included many discourse referents in a short period of time. Moreover, the utterance is an adjectival predicate with no expressed lexical verb, let alone a transitive verb. This illustration exemplifies ASL signers producing SELF

pronouns either in predicates with and/or without a transitive verb, which occurred frequently in the 2008 study (Wilkinson 2008).

Adopting the methodology of the English –self study by Kemmer and Barlow, findings reported robust evidence that the most frequent, thus primary, function of SELF was an emphatic pronoun. The second most frequent function of SELF was reflexive, however was only found in 17%

of the data. Findings drawn from the empirical-based analysis suggested that SELF forms serve as an emphatic pronoun but can also function as a reflexive.

Another point to consider is that numerous studies found that reflexive pronouns are not obligatory in ASL whereas reflexives are obligatory in spoken languages (Koulidobrova 2009; Sandler and Lillo-Martin 2006).

Furthermore, studies on other signed languages (e.g. Croatian, Israeli, Russian, and the Netherlands) found reflexives to be optional (Alibašić Ciciliani and Wilbur 2006; Kimmelman 2010; Meir 1998). Alibašić Ciciliani and Wilbur (2006) wrote “the traditional categorization of this pronoun form

‘reflexive’ is somewhat misleading” (Alibašić Ciciliani and Wilbur 2006:

100), complementing what recent studies found. To date, these studies have not taken into account the possible linguistic or social variation of SELF or more broadly, a grammatical morpheme in ASL. Given that the category of SELF includes three pronouns that carry specific semantic and grammatical properties, this serves as a prime candidate to conduct a study on morpho- syntactic variation in signed languages.

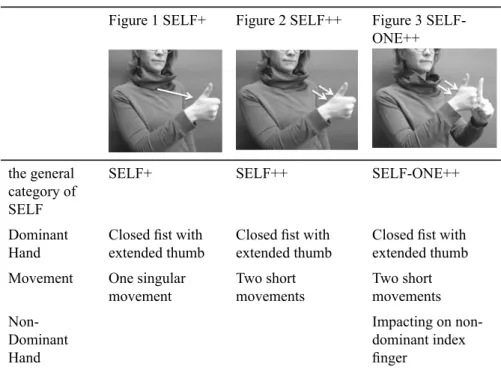

4.1. Phonological shape of SELF

Previous literature described SELF by either one or two forms that can be modified by location and movement (Baker-Shenk and Cokely 1980; Kegl 2003, 2004; Koulidobrova 2009; Liddell 2003; Lillo-Martin 1995, 2003;

Sandler and Lillo-Martin 2006; Tennant and Brown 1998; Stokoe, Caster- line, and Croneberg 1965). Wilkinson (2008) found three distinct forms of SELF, which are encompassed into a general category of SELF.

All three SELF pronouns overlap in handshape, employing a closed fist with an extended thumb. Two variants are produced with one hand while another variant involves a dominant hand impacting on a non-dominant index finger. Movement marks number in SELF forms. Singular forms of SELF are produced with either one or two straight movements whereas plural forms are realized with a sweeping arc movement. Also, movement denotes specific semantic/pragmatic cues. If a signer produces a straight movement

(often with a forceful energy), then the function of the SELF form denotes an emphatic marker that clearly specifies the pragmatic independence of the action undertaken (and/or expected) by the referent coded as SELF+.

Location of SELF pronouns marks person. The location of SELF is typi- cally situated in the signing space; however, SELF may be manipulated in two ways. First, the signed form moves toward the target referent (possibly the speaker and/or referents in the immediate physical space including the addressee). Second, SELF can be modified by a change of orientation, which is more discernable with a phonological change by either the orientation of wrist or elbow. For the sake of consistency, SELF is a general term that refers to the category of three distinct phonological forms. As for these three SELF variants, they are coded as SELF+, SELF++, and SELF-ONE++.

Along with coded representation, formal properties of these three SELF pronouns are summarized in Table 1:

Table 1. Phonological descriptions of SELF and their grammatical functions (table and photos reprinted at the courtesy of Gallaudet University Press – Sign Language Studies)

Figure 1 SELF+ Figure 2 SELF++ Figure 3 SELF- ONE++

the general category of SELF

SELF+ SELF++ SELF-ONE++

Dominant

Hand Closed fist with

extended thumb Closed fist with

extended thumb Closed fist with extended thumb Movement One singular

movement Two short

movements Two short movements Non-Dominant

Hand

Impacting on non- dominant index finger

Grammatical

functions independent emphatic, reflexive*

all emphatics (not independent emphatic),

reflexive, formulaic sequence

all emphatics (not independent emphatic) with a focus marker

Notes:

– the symbol (+) refers to the number of movements produced in the phono- logical shape of SELF. For instance, SELF+ forms one movement whereas SELF++ realizes two movements.5

– * independent emphatic refers to a specific SELF variant that pragmatically denotes the independence of the action undertaken by the referent.

Rather than viewing three forms of SELF as reflexive forms, they are emphatic pronouns that may function as a reflexive. Henceforth, the SELF forms will not be referred to as reflexives but instead by the following terms:

forms, variants, or pronouns.

4.2. Grammar of SELF

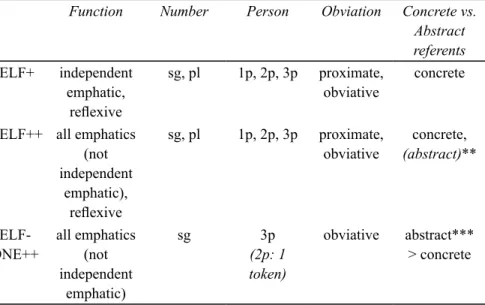

This section briefly introduces the grammatical categories and distinctions that are marked in the set of SELF forms. Wilkinson (2008) conducted gram- matical analyses of SELF, and found that each variant had their own gram- matical function. While the three forms of SELF function as an emphatic marker, these forms do not convey similar grammatical distinctions.

Wilkinson (2012) found that SELF pronouns are grammatically marked for person, number, and obviation (see below). The semantic category of concrete and abstract referents affects the choice of SELF forms. Given the findings from both analyses, it is suggested that SELF pronouns carry a more complex grammatical system than previously described in other works.

Previous studies have identified number and person as two grammatical modifications expressed in SELF forms (to name a few: Kegl 20046; Sandler and Lillo-Martin 2006). However, there remains disagreement on whether signed language pronominal systems grammatically mark person or not, let alone carry distinctions of person (e.g. 1st person, 2nd person, 3rd person, non-1st person, dual, trial, multiple, etc.). Although relevant, the dialogue about grammatical categories and its distinctions in signed language pronom- inal systems is beyond the scope of this paper but I can refer the reader to McBurney (2004), Meier (1990), and Alibašić Ciciliani and Wilbur (2006) among others for further discussion.

Many papers have identified a contrast between inclusion and exclusion in the personal pronominal systems of signed languages (Alibašić Ciciliani and Wilbur 2006; Kegl 2004; Sandler and Lillo-Martin 2006; McBurney 2004).

Although I did not examine the category of exclusion in SELF pronouns, it is possible that SELF pronouns express two distinctions of inclusion and exclu- sion by modifications of location and movement. For instance, an exclusive plural form of SELF++ may be realized by moving with a horizontal arc from the contralateral to the ipsilateral side in the signing space. But instead, I take this further by proposing that there is a grammatical category of obvia- tion in the ASL pronominal system of SELF.

The discussion on the grammatical category of obviation mainly draws on studies of Algonquian languages in North America (e.g. Aissen 1997;

Muehlbauer 2012; Wolfhart 1973). Within the 3rd person category, there are two distinctions of obviation that are identified as proximate and obviative within the 3rd person category.7 The prominence ranking of 3rd person forms is determined by discourse (and physical) span especially in cases where there are more than one 3rd person referents. The most prominent 3rd person referent in the discourse span will be proximate whereas all other less-prom- inent 3rd person referents are obviatives (Aissen 1997). Obviative forms are characterized as morphologically marked 3rd person forms while 3rd person proximates are generally morphologically unmarked.

The distribution of SELF revealed that signers appeared to be sensitive to one’s physical proximity with respect to the target referent in discourse space, which affected their choice of SELF forms. When target referents are in the signers’ immediate physical setting, signers do not employ SELF- ONE++, but only SELF+ and SELF++. Conversely, signers consistently chose SELF-ONE++ for target referents that were not physically proxi- mate in the discourse context.8 Furthermore, grammatical judgment by ASL signers consistently rejected the use of SELF-ONE++ for 1st person and 2nd person referents. The asymmetry in the usage of SELF forms suggests that SELF-ONE++ marks obviative while both forms of SELF+ or SELF++ may function either proximate or obviative.

However, the interaction of these forms and obviation along with other grammatical categories begs more in-depth analyses, specifically to learn more about what factors appear to permit signers to use SELF++ for obvia- tive referents. The analysis found that the choice of SELF pronouns is affected by the physical proximity between the signer and the target referent.

Also, not only physical proximity, but topicality within the discourse appears to determine which SELF form is employed in ASL.

The semantic category of concrete and abstract referents (animacy) affects the choice of SELF forms in ASL discourse. The analysis found that nearly all abstract referents like idea were marked with SELF-ONE++ whereas all three SELF forms may be used to mark concrete referents. Data reported that signers never produced SELF+ in reference to abstract representations. More importantly, the study indicated that there is an interaction between obvia- tion and animacy of target referents that drives the choice of SELF pronouns, including grammatical categories of person and number. Interestingly, this pattern is also noted in Algonquian languages (Wolfhart 1973).

The analysis found that the SELF pronominal system is more complex than traditionally described. Thus, these three SELF pronouns are better characterized rather simply as three morphemes specified by grammatical and semantic categories by means of the description of their formational properties as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Distinctions of grammatical and semantic categories encoded in SELF pronouns

Function Number Person Obviation Concrete vs.

Abstract referents SELF+ independent

emphatic, reflexive

sg, pl 1p, 2p, 3p proximate,

obviative concrete

SELF++ all emphatics (not independent

emphatic), reflexive

sg, pl 1p, 2p, 3p proximate,

obviative concrete, (abstract)**

SELF-

ONE++ all emphatics (not independent

emphatic)

sg 3p

(2p: 1 token)

obviative abstract***

> concrete

**italicized abstract denotes that there appear to be other devices at work when a signer marks an abstract referent with the SELF++ form. There were only two instances of marking abstract referents with SELF++ in the ASL corpus.

***The symbol (>) shows there is a bias in animacy with respect to the SELF variant. When one refers to an abstract referent, then SELF-ONE++ will be used.

However, the SELF-ONE++ form can be used with concrete referents, indicating that animacy is an important determiner in the choice of SELF variants.

The following section addresses the methodology for genre sampling, data coding and the extraction of SELF from the ASL corpus.

4.3. The ASL corpus: Methodology of genre sampling, data coding and extraction

The study was drawn on a collection of ASL productions in naturalistic contexts of discourse use. Language sampling of the ASL corpus was built on a variety of repertoires that are publicly available; videotapes and vlogs, including monologues, 2-person conversations, and narratives. Monologues included two sub-types: presentations and vlogs. Topics in monologues and two-person conversations ranged from movies and television programs, scary and memorable experiences, family history, how the solar system works, and informing why one prefers cats over dogs (or vice versa). Also, deaf and language related topics were covered, like the closure of residential schools, the legal recognition of language and human rights. The duration of mono- logues ranged from 1.5 minutes to 2 hours while the duration of 2-person conversations averaged 45 minutes. Narratives included both elicited narra- tives of Pear stories (Chafe 1975) and Frog, where are you stories (Mayer 1969) and stories for children. The duration of narratives ranged from two to five minutes. The American data was approximately 8.5 hours while the Canadian set contained nearly 24 hours, totaling approximately 32 hours of video recordings of ASL. The data is based on an ASL corpus with data that ranges from 1999-2011 in Canada and the United States.

Data coding involved three steps to code for SELF usage in both Cana- dian and American variations. The first step involved capturing and anno- tating three phonological variants of SELF in video sources. Each utterance with a SELF token was annotated by a gloss that is represented by English- translated equivalents. The following step involved organizing all tokens of SELF according to their phonological variants, coded as SELF+, SELF++, and SELF-ONE++. These variants were categorized within Canadian and American data sets. Each occurrence of SELF was counted as one token of SELF, and these tokens of SELF pronouns were typed and sub-typed according to particular grammatical and semantic categories (e.g. argu- ment emphatic9, 1st person, proximate, concrete). By conducting an analysis of token frequency, this would permit distributional analyses on SELF within and across regional variations. All codings were entered into an Excel database.

Out of 32 hours of the ASL corpus, 351 utterances of SELF were extracted and then coded for analysis. However, ambiguity and formulaic expressions resulted into 26 SELF tokens to be discarded. First, ambiguity arose when a signer produced two SELF forms in sequence such as SELF++

SELF-ONE++.10 Second, all formulaic expressions of THINK^SELF+ were removed from the analysis since these expressions do not carry a similar gram- matical function to other SELF forms. Similar to compounding processes in signed languages, THINK^SELF+ is a fused construction of one lexical sign and a grammatical sign that has undergone extensive phonological reduc- tion and semantic bleaching. However a detailed discussion about formulaic expressions of THINK^SELF+ is beyond the scope of this paper but the reader is referred to Wilkinson (2008) for further description.

The remaining 325 instantiations of SELF were categorized according to token and type frequency within each variation and across both variations.

The Canadian ASL corpus provided 209 tokens of SELF while 116 tokens were seen in the American data. Although the Canadian corpus produced more SELF tokens than the American corpus, the duration of Canadian data (23.8 hours) is far greater than the American counterpart (8.6 hours). The large discrepancy in the size of the corpora will be an important point, which will be returned to later in the paper.

The following section discusses genre effects emerging in both Canadian and American variations of ASL.

5. The distribution of SELF across genres

The distributional analysis illustrated interesting behaviors of SELF usage in American and Canadian signers. Data indicates that genre plays a role in ASL discourse as both Canadians and Americans did not produce SELF similarly in narratives, monologues, and 2-person conversations. The following discussion will involve the overall distribution of SELF within and across both variations. Asymmetry was found across three distinct forms of SELF, suggesting that genre functions as a linguistic factor that contributes to morphosyntactic variation.

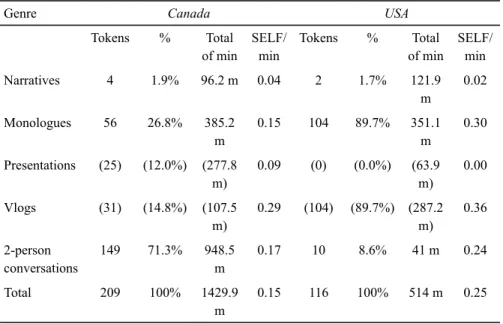

Data reported a total count of 209 SELF tokens in Canadian ASL whereas the American variation yielded 116 tokens of SELF. Table 3 illustrates the distribution of SELF tokens typed by genre in both Canadian and American variations. To determine the frequency of SELF within the given genre of one language variation, values were computed by using the following formula:

[token count divided by total minutes] as followed in Table 3.11

Table 3. Overall distribution of SELF by genre types in Canadian and American variation of ASL. Percentage is based on the number of tokens of the genre divided by the total number of tokens reported in the given language variation.

Genre Canada USA

Tokens % Total of min SELF/

min Tokens % Total of min SELF/

min

Narratives 4 1.9% 96.2 m 0.04 2 1.7% 121.9

m 0.02

Monologues 56 26.8% 385.2

m 0.15 104 89.7% 351.1

m 0.30

Presentations (25) (12.0%) (277.8

m) 0.09 (0) (0.0%) (63.9 m) 0.00 Vlogs (31) (14.8%) (107.5

m) 0.29 (104) (89.7%) (287.2 m) 0.36 2-person

conversations 149 71.3% 948.5

m 0.17 10 8.6% 41 m 0.24

Total 209 100% 1429.9

m 0.15 116 100% 514 m 0.25

The distribution shows that Canadians, overall, appear to use SELF more than Americans. Within the Canadian variation, 2-person conversations yielded 71.3% of SELF forms (149 tokens) while 26.8% and 1.9% were produced in monologues (56 tokens) and narratives (4 tokens) respectively.

In contrast, 89.7% of SELF in the American corpus was seen in monologues (104 tokens) while 8.6% and 1.7% of SELF variants were identified in 2-person conversations (10 tokens) and narratives (2 tokens) respectively.

Both Canadians and Americans rarely produced SELF in narratives as only a total of six tokens were identified in both variations, indicating a robust trend of the paucity of SELF in signed narratives. The distribution of SELF pronouns clearly demonstrated variation across genre types and but also within language variation.

The most striking aspect of the given distribution was that genre patterns were not identical in Canadians and Americans except for narratives. Both Canadians and Americans employed 0.04 and 0.023 SELF forms per minute, illustrating an extremely low frequency of SELF usage in narratives. As for monologues, Americans realized 0.30 SELF forms per minute compared to Canadians who only produced 0.15 SELF forms per minute. Americans

employed SELF twice more than Canadians in monologues, suggesting there is variation with respect to the employment of SELF in ASL discourse.

The discussion about the sub-genres of monologues and their distributional patterns will be explored in detail below.

The frequency of SELF usage in 2-person conversations differs between Canadians and Americans. Americans expressed 0.24 SELF forms per minute compared to Canadians who only produced 0.17 SELF forms per minute.

This finding indicates that Americans use SELF twice more than Canadians in 2-person conversations. However there was a very small sampling of 2-person conservations in the American variation, one has to be cautious in interpreting the analysis. There were only 41 minutes of 2-person conver- sations in the American corpus in contrast to 15.8 hours in the Canadian corpus. To confirm and/or reject asymmetry in the distribution of 2-person conversations between Canadian and American variation will require a larger sampling in subsequent studies.

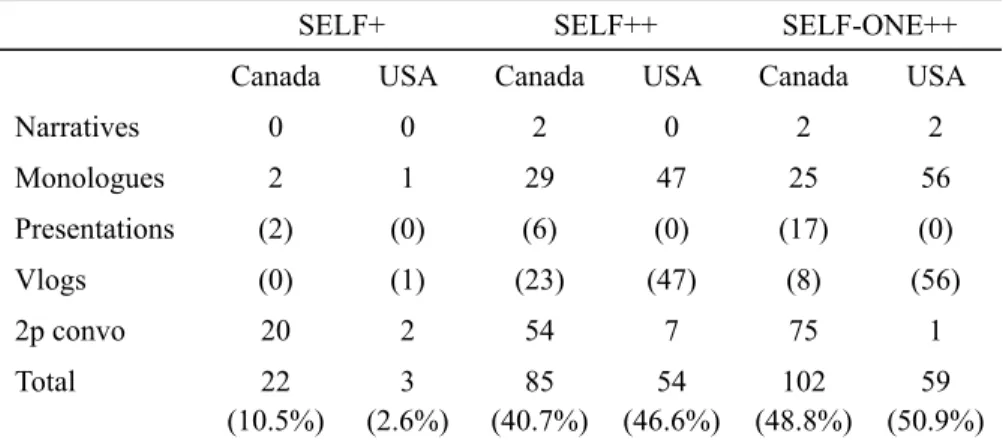

The distribution of the three SELF pronouns revealed surprising patterns in Canadian and American variations. Differences in the employment of specific SELF forms were evident among Canadian and American signers, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Overall distribution of SELF pronouns by regional variation. Percentage is based on the number of tokens of the genre divided by the total number of tokens reported in the given language variation.

SELF+ SELF++ SELF-ONE++

Canada USA Canada USA Canada USA

Narratives 0 0 2 0 2 2

Monologues 2 1 29 47 25 56

Presentations (2) (0) (6) (0) (17) (0)

Vlogs (0) (1) (23) (47) (8) (56)

2p convo 20 2 54 7 75 1

Total 22

(10.5%) 3

(2.6%) 85

(40.7%) 54

(46.6%) 102

(48.8%) 59 (50.9%) The distributional analysis showed that the overall count is higher in the Canadian corpus compared to the American counterpart. The tokens of SELF forms in both variations ranged from 3 to 102. Within the Canadian varia- tion, 48.8% of the SELF set was found in SELF-ONE++ while 40.7% and 10.5% of SELF variants appeared in SELF++ and SELF+ respectively. In

contrast, Americans produced slightly balanced sets of SELF-ONE++ with 50.9% and SELF++ with 46.6% while 2.6% of SELF+ was produced in the SELF set. The range of SELF forms clearly demonstrated variation across phonological distribution and within both Canadian and American variations.

Token frequency showed that Canadian signers, overall, produced more SELF variants than American signers. Interestingly, Canadians employed SELF-ONE++ twice more compared to Americans. However, we must take into account that most SELF-ONE++ occurred in 2-person conversations in the Canadian data. Thus, it is precarious to assume that Canadians show a strong bias for SELF-ONE++ compared to Americans due to a very large discrepancy between 41 minutes of 2-person conversations in the American corpus and the 15.8 hours in the Canadian corpus. Thus, this will require more American data to counterbalance the 15.8 hours of Canadian 2-person conversations to continue discussion about potential asymmetry in SELF-ONE++. However it is important to note that frequency analyses revealed that American signers employed SELF nearly twice more compared to Canadian signers, given the overall frequency ratio of 0.25 SELF/min to 0.15 SELF/min respectively.

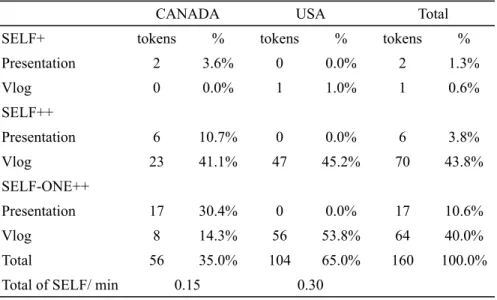

A closer examination of the monologic data yielded an interesting distri- butional pattern of SELF in subtypes of presentations and vlogs among Americans and Canadians as in Table 5.

Table 5. Distribution of SELF forms in subtypes of monologues: presentations and vlogs in Canadian and American signers. To determine the frequency of SELF usage within a genre, values were formulated as [token count di- vided by total minutes].

CANADA USA Total

SELF+ tokens % tokens % tokens %

Presentation 2 3.6% 0 0.0% 2 1.3%

Vlog 0 0.0% 1 1.0% 1 0.6%

SELF++

Presentation 6 10.7% 0 0.0% 6 3.8%

Vlog 23 41.1% 47 45.2% 70 43.8%

SELF-ONE++

Presentation 17 30.4% 0 0.0% 17 10.6%

Vlog 8 14.3% 56 53.8% 64 40.0%

Total 56 35.0% 104 65.0% 160 100.0%

Total of SELF/ min 0.15 0.30

Investigating the count of SELF variants sub-typed by monologues demon- strated that signers produced most SELF forms in vlogs compared to pres- entations. Data illustrated a total of 56 occurrences of SELF in the Canadian variation while 104 SELF tokens were reported in the American variation.

The tokens of SELF in both variations studied ranged from 1 to 56, which were typed by presentations and vlogs. The highest reported number of SELF variant in a genre type was SELF-ONE++ in the American variation with 56 tokens. The next most frequent type was 47 tokens of SELF++ in the Amer- ican variation. In contrast, the Canadian variation produced only two tokens of SELF+ in presentations while the American variation showed one token of SELF+ in vlogs. Americans, in total, produced 104 instances of SELF in their vlogs whereas there were no SELF forms realized in their presenta- tions. However, Canadian vloggers produced 31 occurrences of SELF, which was slightly more than Canadian presenters who realized 25 SELF tokens.

Differences in the distribution of SELF indicated variation across monologic subtypes and within both variations in Canada and the United States.

The cross-variation pattern revealed that Americans employed SELF on a higher frequency with 104 tokens in 5.9 hours compared to 56 tokens real- ized by Canadians in 6.4 hours. Intriguingly, Americans did not produce any SELF forms in presentations, and this contrasted with Canadians as they did use SELF forms in presentations, producing 0.09 SELF forms per minute.

As for vlogs, Americans used 0.36 SELF pronouns per minute compared to Canadians who expressed 0.29 SELF pronouns per minutes, indicating that Americans demonstrated a higher usage of SELF compared to Canadians.

Canadians demonstrated more of a balanced usage of SELF forms in both vlogs and presentations whereas Americans demonstrate a strong bias of SELF usage in vlogs as there were no tokens of SELF observed in American presentations. Given the frequency distribution of presentations and vlogs, this suggests there is variation with respect to the employment of SELF in ASL discourse. Preliminary findings indicate that genre plays an important role in SELF usage, providing compelling evidence for morphosyntactic variation in ASL.

In summary, data showed that both Canadian and American signers often produced SELF pronouns in monologues and 2-person conversations but not in narratives. Within the monologue type, Canadian signers realized a balanced usage of SELF in both subtypes of vlogs and presentations. By contrast, American signers expressed SELF forms in vlogs but not in pres- entations. Specifically, Canadian presenters produce SELF forms whereas American presenters produced none. In contrast, American vloggers used more SELF pronouns than Canadian vloggers. Overall, the occurrence of

SELF in American monologues was double compared to Canadian mono- logues. This presents robust evidence of genre effect at work, demonstrating systematic differences between Canadian and American ASL communities.

6. Discussion

Findings of this study yielded interesting patterns of social and linguistic factors of a special set of SELF pronouns as there were effects of region and genre that contributed to morphosyntactic variation in ASL. Differences in patterns across genres beg us to inquire about what factors motivate signers to incorporate (or not) SELF in specific genres, which should be explored in future studies. Given these sociolinguistic differences, this study presents preliminary evidence of genre effect, language variation across but also within both variations of Canadian and American ASL. Finding an effect of genre types was also reported in the study by McKee et al. (2011), i.e., New Zealanders expressed more subject nominals during interviews compared to informal conversations. Their finding involved two different types of 2-person conversations, with register having a significant effect: an increase in formality predicts a more frequent expression of subject nominals. This finding somewhat compares to the difference in the distribution of SELF in monologues, specifically in subtypes of vlogs and presentations among Canadian and American signers. Moreover, SELF was rarely produced in ASL narratives in both variations. In turn, the pattern revealed that the occur- rences of SELF are not uniform across genres, and the difference may be partially explained by the choice of discourse topics.

Genre clearly influences the use of SELF, drawing mainly on differences of SELF production in vlogs and presentations. While both presentations and vlogs are similar in nature, one has to consider slight differences between these two sub-types that may affect ASL discourse. Technology appears to shape how discourse space is defined in terms of the physical and perceived realm of the camera captured on the video camera and/or webcam. Also, the presence and/or lack of discourse interlocutors appear to play a role in ASL discourse of presentations and vlogs respectively. Presentations typically involve a signer who presents discourse text to a video camera that is moni- tored by a cameraman. As for vlogs, signers are in a setting where they create text via the video camera in their computer. There may be differences in the relationship of physical space between sub-types. Vloggers are aware of a reduced, defined boundary of a visual medium determined by their camera in their computers, whereas a free-standing video camera permits the signer to

be more mobile in their physical space. Furthermore, the video camera may be re-oriented in order to follow the path of the signer to maintain visibility of the signer, where the vlogger’s webcam is typically stationary.

Comparing vlogs and presentations (and interactive discourse) reveals a difference in the dimensions of physical space. The nature of a presentation was often so that a presenter signed to a video camera that was monitored by a cameraman (and/or others). Although the cameraman may not intention- ally be a conversational partner, the setting may provide the signer with a sense of a 2-person conversation by picking up cues from the cameraman, albeit reduced in the sense of discourse context. Due to its technological limitations, the webcam determines the allocated visible space, which influ- ences the vlogger to compress their physical space proportionally to what the webcam is capable of capturing. Vloggers typically situate themselves in a setting where they create a discourse text directly to the video camera with no interlocutor in the immediate physical environment. Also, vloggers can view themselves while they are producing their vlogs in the computer, suggesting a different type of discourse feedback (language monitoring). But it is unknown to me if vloggers choose to view themselves while they make their vlogs or turn off their “viewer screen” while they sign to the computer.

This trend was also observed in a study by Keating, Edwards and Mirus (2008) where they detailed how signers modified their language use in response to new technologically mediated space (e.g. video phone). Further- more, the creation of a vlog involves the signer seeing themselves signing while making their compositions, resulting in visual feedback at work. The physical (and psychological) space appears to affect the signer by manip- ulating their signing space. A reduction in visual space will manipulate language use in some fashion, paralleling findings from a psycholinguistic study by Emmorey et al. (2009). They found normal-sighted signers who experienced tunnel vision condensed their physical space of signing by shortening their signed movements, indicating that visual feedback plays a role in language production (Emmorey et al. 2009). These studies noted that visual feedback is important as normal-sighted signers are sensitive to visual dimensions that would potentially lead to a change in language production.

Nowadays, a growing number of signers are taking advantage of vlog- ging on a regular basis thanks to cheap and efficient technology. Vlogging appears to be a new genre in signed languages as it is a rapidly growing domain popular to many vloggers and viewers. The current study character- ized differences between Canadian and American signers; however, since vlogging constitutes an emerging genre, I predict that linguistic behaviors in vlogging will evolve over time. Therefore, it is a unique opportunity

for signed language linguists to capture the dynamic nature of vlogging.

Not only will we be able to build synchronic studies of vlogs, we can also develop diachronic studies of individual vloggers to observe which linguistic trends emerge over time. The opportunity to compare and contrast linguistic characteristics in experienced vloggers and in new vloggers who just started vlogging, allows further observation of the effects of visual feedback on language use.

Findings of linguistic patterns in vlogs and presenters could benefit inter- preter training programs as these settings are somewhat parallel to situations in which interpreters often work. For instance, vlogging resembles an inter- pretation setting where an interpreter would interpret a phone conversation through a visual medium (e.g. video relay service). An interpreter who is on a stage interpreting for a large and less interactive audience resembles the physical setting of a deaf signer who presents her material directly to the camera in a studio. Although there may be not much interaction taking place in the studio, often the deaf presenter has, at least, minimum interaction with the camera person and/or more people in the studio. Given the slight differ- ences in two subtypes of monologues, they give us more insights into how ASL signers use grammatical signs in specific ways. In closing, this domain is extremely new, introducing us to an exciting period in signed language linguistics.

Along with a range of genres, this study underscores the importance of building and maintaining a data corpus of a given language variation over time. Data collection captures a sense of language use in a specific time within the language community. Not only that, data collection also involves collecting a variety of genres that provide a representative sampling of the language. Given the nature of small data sampling in signed language research, we often limit ourselves to a specific genre whether they are narra- tives, monologues, or 2-person conversations. This study reminds us that the studied component may be not equally distributed across genres and/

or across language users. Fortunately, there is a growing trend in terms of building corpora of signed languages in many research centers in the world.

It is hoped that future studies will conduct a diachronic study in addition to synchronic analyses. These studies are invaluable, as they will provide insights into social and linguistic factors and the role they play in shaping language variation within and across variations of a signed language.

7. Conclusion

There remains an extensive amount of work to understand more about morphosyntactic variation in a signed language. The comparative analysis of SELF in Canadian and American ASL illustrated emerging evidence of morphosyntactic variation in ASL. Sociolinguistic factors of genre and region influenced the usage of SELF, corroborating with other sociolin- guistic studies that found these factors as driving effects in sociolinguistic variation. Future studies of ASL grammatical morphemes should be explored in a variety of genres and controlled by sociolinguistic variation. It is hoped that future cross-linguistic studies will contribute important clues about the usage and patterns of grammatical morphemes and language change in signed languages in general.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by University of Manitoba Research Grant (#35263) and a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) Research Development Initiative. This project could not have been conducted without assistance and support of my research assistants, Karen Bryant and Dana Zimmer. I also acknowledge Brenna Haimes-Kusumoto for her assistance with a portion of video recording for the Canadian ASL corpus and Sherra Hall for editorial assistance. I thank all Canadian and American participants, vloggers, and presenters for their involvement with this study.

Notes

1. I thank an anonymous reviewer for bringing the reference to my attention.

2. The term of vlogger refers to a person who makes video blogs that are uploaded to the internet for public viewing.

3. For further discussion about passivization in ASL, see Janzen, O’Dea, and Shaffer (2001).

4. Koulidobrova (2009) indicates that other studies have proposed various grammatical descriptions of SELF, such as a “definiteness marker”

(Fischer and Johnson 1982), a “specificity marker” (Wilbur 1996), and a

“presuppositionality marker” (Mathur 1996). Liddell (2003) identified a set of SELF forms that carried a significant semantic-pragmatic function but did not classify these forms as anaphoric forms similar to traditional analyses.

5. Since there is no standard written representation for ASL lexicon, signed language linguists rely on translation equivalents of their surrounding written languages known as glossing. While it is not my intention to provide the best translated written equivalents of SELF variants, I aimed to assign codified written representations of these three SELF pronouns for the sake of clarity.

6. Kegl (2004) proposed that an ASL reflexive form also encodes a grammatical distinction of [–intimate]; however, it remains unclear to what degree intimacy is determined in her 2004 analysis on reflexives in ASL.

7. Wolfhart (1973) explained that obviation has been referred to as the 4th and/

or 5th pronoun, but he maintained that both distinctions of proximate and obviative fall into the 3rd person category.

8. The form of SELF-ONE++ is phonologically complex as it employs both hands compared to the other two forms produced with only one hand. Not only is there a difference in phonological structure, the usage of SELF-ONE++

in ASL discourse revealed a consistent form-function relationship where target referents were abstract inanimates and/or distant either in physical or discourse span; however, further investigation is needed to learn more about their functions.

9. When a SELF emphatic marker, is expressed as a free-standing noun phrase in subject position, it is identified as an argument emphatic.

10. Interestingly, the pattern of reduplicating SELF variants in a sequence reveals that SELF-ONE++ always occurs after SELF++, but not vice versa. No sequence was found with a pragmatic marker of SELF+ with other two SELF variants.

11. For instance, the frequency of SELF for narratives in the Canadian variation was formulated as [4 tokens / 96.2 total minutes], which yielded 0.04 SELF/

min.

References Aissen, Judith

1997 On the syntax of obviation. Language 73: 705–750.

Alibašić Ciciliani, Tamara, and Ronnie Wilbur

2006 Pronominal system in Croatian Sign Language. Sign Language and Linguistics 1: 95–132.

Baker-Shenk, Charlotte, and Dennis Cokely

1980 American Sign Language: A Teacher’s Resource Text on Grammar and Culture. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Chafe, Wallace

1975 The Pear Film. (Retrieved August 5, 2011). http://www.linguistics.

ucsb.edu/faculty/chafe/pearfilm.htm Croft, William

2001 Radical Construction Grammar: Syntactic Theory in Typological Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Emmorey, Karen, Nelly Gertsberg, Franco Korpics, and Charles E. Wright

2009 The influence of visual feedback and register changes on sign language production: A kinematic study with deaf signers. Applied Psycholinguistics 30, 187–203.

Fischer, Susan and Robert Johnson.

1982 Nominal markers in ASL. Paper presented at the Linguistic Society of America (LSA) Winter Meeting, San Diego.

Janzen, Terry, Barbara O’Dea, and Barbara Shaffer

2001 The construal of events: Passives in American Sign Language.

Sign Language Studies 1 (3): 281–310.

Keating, Elizabeth, Terra Edwards, and Gene Mirus

2008 Cybersign: Impacts of new communication technologies on space and language. Journal of Pragmatics 40 (6): 1067–1081.

Kegl, Judy

2003 Pronominalization in American Sign Language. Sign Language and Linguistics 6 (2): 245–265.

2004 ASL syntax: Research in progress and proposed research. Sign Language and Linguistics 7 (2): 173–206.

Kemmer, Suzanne

1995 Emphatic and reflexive –self: Expectations, viewpoint, and subjectivity. In Subjectivity And Subjectivisation: Linguistic Perspectives. Dieter Steiner and Susan Wright (eds.), 55–82.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

2003 Human cognition and the elaboration of events: Some universal conceptual categories. In The New Psychology of Language:

Cognitive and Functional Approaches to Language Structure 2, Michael Tomasello (ed.), 89–118. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kemmer, Suzanne, and Michael Barlow

1996 Emphatic –self in discourse. In Conceptual Structure, Discourse and Language, Adele Goldberg (ed.), 231–248. Stanford, CA:

Center Study Language and Information.

Kimmelman, Vadim

2010 Reflexive pronouns in Russian Sign Language and Sign Language of the Netherlands: Modality and universals. Poster presented at Theoretical Issues in Sign Language Research (TISLR) 10, West Lafayette, IN.

König Ekkehard, and Peter Siemund

2000 The development of complex reflexives and intensifiers in English.

Diachronica XVII (1): 39–84.

Koulidobrova, Elena

2009 SELF: Intensifier and ‘long distance’ effects in ASL. ESSLLI 2009. http://tinyurl.com/3qnhclf (Retrieved July 27, 2011).

Liddell, Scott

2003 Grammar, Gesture, and Meaning in American Sign Language.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lillo-Martin, Diane

1995 The point of view predicate in American Sign Language. In Language, Gesture, and Space, Karen Emmorey, and Judy Reilly.

(eds.), 155–170. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

2003 Pronouns, indices, and agreement: Commentary on papers by Lacy and Kegl. Sign Language and Linguistics 6 (2), 267–276.

Lucas, Ceil, and Robert Bayley

2011 Language variation in signed languages: Recent research on ASL.

Language and Linguistics Compass 5 (9): 677–690.

Lucas, Ceil, Robert Bayley, and Clayton Valli

2001 Sociolinguistic Variation in American Sign Language. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Lucas, Ceil and Clayton Valli

1992 Language Contact in the American Deaf Community. San Diego:

Academic Press.

Mathur, Gaurav

1996 A presuppositionality marker in ASL. Ms. MIT.

Mayer, Mercer

1969 Frog, where are you? New York: Dial Press.

McBurney, Susan L.

2004 Referential morphology in signed languages. Ph.D dissertation, University of Washington.

McKee, Rachel, Adam Schembri, David McKee, and Trevor Johnston

2011 Variable “subject” presence in Australian and New Zealand sign language. Language Variation and Change 23, 375–398.

Meier, Richard P.

1990 Person deixis in American Sign Language. In Theoretical Issues in Sign Language Research 1: Linguistics. Susan D. Fischer, and Patricia Siple (eds.), 175–190. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Meir, Irit

1998 Syntactic-semantic interaction in Israeli sign language verbs: The case of backwards verbs. Sign Language and Linguistics 1, 3–37.

Muehlbauer, Jeff

2012 The relation of switch-reference, animacy, and obviation in plains cree. International Journal of American Linguistics 78 (2), 203–

238.

Padden, Carol A.

1988 Interaction of Morphology and Syntax in American Sign Language. New York: Garland.

Sandler, Wendy, and Diane Lillo-Martin

2006 Sign language and Linguistic Universals. Cambridge, UK:

Cambridge University Press.

Schembri, Adam, Kearsy Cormier, Trevor Johnston, David McKee, Rachel McKee, and Bencie Woll

2010 Sociolinguistic variation in British, Australian and New Zealand sign languages. In Sign Languages. Diane Brentari (ed.), 479–

501. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schembri, Adam, and Trevor Johnston

2006 Sociolinguistic variation in in Australian Sign Language project:

Grammatical and lexical variation. Paper presented at the 9th International Conference on Theoretical Issues (TISLR).

Universidade Federal de Sante Catarina, Florianopolis, Brazil, December 2006.

Stokoe, William, Dorothy Casterline, and Carl Croneberg,

1965 The Dictionary of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Tennant, Richard, and Marianne Gluszak Brown

1998 The American Sign Language Handshape Dictionary. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Travis, Catherine E.

2007 Genre effects on subject expression in Spanish: Priming in narrative and conversation. Language Variation and Change 19 (2): 101–135.

Trousdale, Graeme

2011 Variation and education. In Analysing Variation in English. Warren Maguire, and April McMahon (eds.), 261–279. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Trudgill, Peter

2002 Sociolinguistic Variation and Change. Washington: DC:

Georgetown University Press.

Van Herreweghe, Mieke, and Myriam Vermeerbergen

2006 Interrogatives and negatives in Flemish sign language. In Interrogative and Negative Constructions in Sign Languages.

Ulrike Zeshan (ed.), 225–256. (Sign Language Typology 1.) Nijmegen: Ishara Press.

Wagner, Susanne

2008 English dialects in the Southwest: morphology and syntax. In Varieties of English - The British Isles. Bernd Kortmann, and Clive Upton (eds.), 417–439. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Wilbur, Ronnie

1996 Focus and specificity in ASL structures containing SELF.

Presentation at the Winter Meeting of the LSA. San Diego.

Wilkinson, Erin

2008 SELF: Does it behave as a reflexive pronoun in American sign language? Proceedings of the Eighth Annual High Desert Linguistics Society conference 7, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM.

2012 Unlocking the grammatical system of SELF: A functional description. Presentation at Visual Language and Visual Learning (VL2), Gallaudet University, Washington, DC.

Wolfhart, H. C.

1973 Plains Cree: A grammatical study. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 63 (5). Philadelphia, PA.

Wulf, Alyssa, Paul Dudis, Robert Bayley, and Ceil Lucas

2002 Variable subject presence in ASL narratives. Sign Language Studies 3 (1): 54–76.

Zeshan, Ulrike

2004 Interrogative constructions in signed languages: Crosslinguistic perspectives. Language 80 (1): 7–38.