Some Notes Concerning the Textile Technology

Pictured in the Keng-chih-Vu

Von Dieteb Kuhn, Cambridge

I

A large number of articles and books about the Keng-chih-Vu have

appeared in the last eighty years. The history of the poems and illus¬

trations, and the details conceming the different editions and editors,

including some comparative analysis' — these have been the main

subjects considered in most of the published hteratme. What exactly is

illustrated in the King-chih-t'u is, however, a question which has not yet

received a satisfactory answer. Mostly the authors simply believed that

the title of an illustration actually indicated its real content. In my

opinion this assumption can no longer be accepted without qualification.

The difficult and confusing history of this most important source for

all later works on agriculture and sericulture demonstrates how little the

literati and artists in the Chinese past were concemed with the life and

method of production in the countryside and in the cities. This lack of

concem is especiaUy noticable in regard to the textile industry, and it

was probably the main reason for the perpetuation, through the centu¬

ries, of a partly incorrect pictorial tradition. Because of its origin and age,

the King-chih-t'u was the object of great admiration; and as the imperial

prefaces and poems show, the aim of its continued reproduction was to

depict how the ancestors had worked in order to encourage agricultme

and textile crafts.

In considering the illustrations we have to distinguish between those

concerned with agricultme and those concemed with silkworm breeding

and textile manufacture. This distinction is necessary not only because

the illustrations portray distinct occupations but also because from the

' MOTONOSUKE Amano : Chügoku konösho kö (Investigations on the old

Chinese agricultural books). Tökyö 1975, p. 101—107, p. 328—343, Joseph

Needham: Science and civilisation in China. Cambridge 1965, vol. 4, 2, p.

106f; Fig. 408. On the history of the King-chih-t'u and references to it in

westem languages, see my article: Die DarsteUungen des Keng-chih-t'u und

ihre Wiedergabe in populär-enzyklopädischen Werken der Ming-Zeit. In:

ZDMG 126 (1976), p. 336—367.

Textile Technology in the King-chih-t'u 409

technical point of view they have not been executed with the same degree

of precision.

Otto Feanke tried to explain the meaning of the poems and the

illustrations in his annotated notes to the translation of the poems of

Lou Shou, but he was only partly successful.*

In his time his work marked an admirable progress because nobody

had previously done any reasonably annotated research on it.*

II

Apart from some rather easy questions conceming reeling and quilling

of sük with which my smaU investigation starts, we find in the Keng-

chih-t'u a very exciting ülustration called "Die Herstellung des Ketten- Fadens", "La chaine" (ching ^ )*, showing a most questionable working process "warping the beam". This illustration would not be of such im¬

portance if it did not show the continuity of Chinese pictorial traditions^

in the later Chinese works on agricultme.

Taf. LXXXII in the book of Feanke«, PI. XLIX m the edition pic-

tmed in Pelliot is called "Das Verwahren der Cocons", "On enterre

• Otto Franke : Keng Tschi T'u. Ackerbau und Seidengewinnung in China.

Hamburg 1913. (Abhandlungen des Hamburgischen Kolonialinstitutes IL).

He has consulted not only Chinese but also western works, e.g. : .T. Goschke-

wrrscH: Über die Seidenzucht. (Aus dem Chinesischen übersetzt). Li: Ar¬

beiten der Kaiserlich Russischen Gesandtschaft zu Peking über China, sein Volk, seine Religion, seine Institutionen, socialen Verhältnisse. (Aus dem Russischen

nach dem in St. Petersburg 1852—57 veröffentlichten Original von Dr. Cabl

Abel und F. A. Mecklenbitbq). Berlin 1858, Bd. 2, p. 509—533. Inspector

General of Customs (Editor) : Imperial Maritime Customs. 2: Special series

No. 3: Silk. Shanghai 1881, p. 45—68; Stanislas Julien: Resume des

principaux traites chinois sur la culture des müriers et l'iducation des vers

ä soie. Paris 1837; Bebthold Laueer: The discovery of a lost book. In: TP 10

(1909), p. 97—106.

» See Otto Franke, op.cit., p. 99,177; p. 101, 178; p. 104, 179; p. 105,180.

< Otto Fbanke, op.cit., Taf XCVI, Taf XCIII. Paul Pelliot: 4 propos

du King Tche T'ou. In: Memoires concemant l'Asie Orientale 1 (1914)

p. 65—122. PI. LVI.

' Precisely on this item, but mainly dealing with the Nung-shu of Wang

Chen (1313 a.d.), I have written a short article: Marginalie zu einigen Il¬

lustrationen im Nung-shu des Wang Chen. In: Zur Kunstgeschichte Asiens.

50 Jahre Lehre und Forschung an der Universität Köln. Hrsg. von Roger

GoEPPBR, Dieter Kuhn, Ulrich Wiesnbr. Wiesbaden 1977, p. 143—152.

There I demonstrated the connection between the illustrations in the Nung-

shu and the Keng-chih-t'u, but at that time I was not aware of the technical

complications involved. An incorrect picture handed down through the cen¬

turies is certainly the most convincing proof of a tradition.

• Otto Franke, op.cit., p. 132, annotations p. 88—89.

410 Dieter Kuhn

les cocons" (chiao chien ^ This is not only the procedure for stor¬

ing the cocoons but also a method of killing the moths in the cocoons to

prevent them from breaking through the cocoons and destroying the

S-shaped 'endless-spun' silk-threads. Killing the moths was necessary

when the silkworm breeder did not have enough experienced workers or

sük-reels at hand. Generally one took salt and sprinkled it over the layers

of cocoons which were spread on the leaves of the Pawlownia tomentosa,

arranged on bamboo frame-works.' This method was called "damping

with salt" {yen i ^ Ib)*- As we know from an annotation of Hsüan Hu

^ a huo of Hsü Kuang-ch'i, author of the Nung-ching ch'üan-shu, it

was not necessary to use salt. Hsü Kuang-ch'i explained®: "When salt

comes into contact with the worms, it sometimes renders them damp;

on this account people nowadays merely put their cocoons into the jars,

and then use some paper, or the extemal wrapper of the bamboo, or the

leaves of the Nelumbium (speciosum), to wrap up a couple of ounces of

salt, which they put on the cocoons. This plan will also do. Only the

mouths of the jars must be well stopped up, so that no air escapes; if this

be done, it does not matter what is put in the jar; never mind salt, even

mud will do."

In Fbankei», Taf. LXXXIV "Das Abhaspeln der Seidenfäden", Pel¬

liot, PI. L "D6vidage des cocons" we get an image of the sUk-reehng

apparatus, generally called sao-ch'i ^ i^, jf§ ; the working process,

"reeling the sük" was named lien ssu ^ H or chih ssu 'tta Ü or of course also sao ssu l|S U- This is not the place to describe the history or the differ¬

ent types'' of the Chinese silk-reehng apparatus, yet comparing the illus-

' Most probably the Ta'an-shu (Book on sericulture) cited in this context

is not the book of Sun Kuang-hsien, compiled in the Wu-tai period which is

completely lost, but that of Ch'in Kuan, about 1090 a.d. having the same

title, because we can find another quotation in the Nung-shu, ch. 20, p. 30a

which deals with the hot-basin silk-reel from this book. The Nung-shu is strik¬

ing evidence of the fact that the Ts'an-shu of Ch'in Kuan was a well-known book but it shows also that the transmitted edition in the Chih-pu-tsu-chai ts'ung-shu is not complete at all . E .g. this cited part is lacking ; it is to be found in the Nung-shu, ch. 20, p. 23a.

' From the Nung-sang chih-shuo (Plain talk about agriculture and seri-

ciüture), a lost work of the Huang-ho region from the Chin or early Yüan

period which is quoted in the Nung-shu of Wang Chen, ch. 20, p. 23 a, we

know that also two other methods to kill the moths were in use : drymg by

sunlight (jih shai H ^) and using the steaming baskets (lung cheng ^ ^).

" Nung-cheng ch'üan-shu, ch. 33, p. 16a. Also translated in: Dissertation

on the silk manufacture and the cultivation of the mulberry; translated from

the works of Tseu-kwang-K'he (Hsü Kuang-ch'i), called also Paul Siu, a

Calao, or Minister of State in China. In : Chinese Miscellany 3 (1849), p. 100.

10 Otto Franke, op. cit., p. 133; annotations p. 172—175.

Textile Technology in the King-chih-t'u 411

trations we recognize that the one of 1769 by Pelliot (which was done

accordhig to the oldest known pictorial tradition of the King-chih-t'u,

that of Ch'eng Ch'i ^qR ^ of the 13th century) is much better than the

pictures of the Japanese (1676) or the Ch'ing (1739(?)) editions demon¬

strating a hot-water reeling process. The latter are too simple. They

forgot the most essential parts like the guiding eyes, the real roller-frame

and the ramping-board. To complete the illustration of the PELLioT-edi-

tion showing a cold-water reeling process, we only have to add the guid¬

ing eyes {ch'ien-yen ^ BS) upon the pan and the driving-belt (huan-

shing ^ |iS) to turn the puQey (ku ^) of the ramping-board (t'ien-t'i-

ch'emm:^-)''-

The Cleveland Museum of Art preserves a scroll dated to the tirst de¬

cade of the 13th century and attributed to Liang K'ai ^ showing

exactly this type of silk-reehng machine. The scroll is named Keng-chih-

t'u (Pictures of tUhng and weaving).'*

Franke'«, Taf. XC and Taf. LXXXIX (1676-edition) "Die Herstel¬

lung des Schußfadens", Pelliot, PI. LV "Appretage du fil" once more

show that the pictures of the Pelliot- edition are done with much more

care and knowledge of the working-process. In the illustration of the

Japanese edition we see the spoofing process (lo ssu H) which foUows

the reehng of the sUk-threads. The sUk-threads of the reel form a skein

which was taken from the reel and placed on a skein-frame (Jto-tu ^)'*

which could be constructed in different ways so as to be movable. Then,

as we can see, came a technique involving throwing the threads (p'ao ssu

iiV^, used mostly by men in North China. It involved the use of a

hand-reel (lo-tzu )^ 7") fixed on a long throwing-pole (p'ao-kan ^ ^).

This throwing or spooling was necessary not only to get the sUk-threads

onto small reels but also to control their quality. One hand guided the

thread and one hand operated the throwing pole. On the other hand the

" We cannot only find a very old description in the Ts'an-shu (Book on

sericulture) of Ch'in Kuan, (see also Joseph Needham : Science and civilisa¬

tion in Ghina. Cambridge 1965, vol. 4, 2, Fig. 409), but also a great number of different types like the northern and the southern silk-reel, the "soundless roller", the reeling-apparatus with a cold-water pan or the hot-water pan. It is however not possible to deal with at this place because it would far over¬

reach the subject of this article.

" Tins terminology follows that of the Ts'an-shu of Ch'in Kuan, eontaui-

ed in the Chih-pu-tsu-chai ts'ung-shu, chi 9, lin p. 2 b — 3 b.

'3 On tho silk-reeling machine see my article The Uth century Book on

Sericulture hy Ch'in Kuan. — A document on Chinese silk-reeling technology.

In: TP (1981) in press.

'* Otto Fbanke, op.cit., p. 134; annotations p. 177—178.

T'ien-kung k'ai-wu, 1637-edition, ch. 1, p. 31a.

" Ts'an-sang ts'ui-pien, 1899, ch. 5, p. 2a.

412 Dieter Kuhn

ülustration on Taf. XC does not show "Die Herstellung des Schußfadens"

but a re-reehng process most probably of the warp-threads, to get a more

even quality of thread and to give them a very soft first twist, a kind of

'vordrehen' or 'filieren'. The process of spooling can be seen again in

Fbanke, Taf. XCIV, but there is no illustration of quilling or doubling

the weft-threads in this 1739(?) edition.

Taf. XCV (Japanese edition) in Feanke, labelled "Die Herstellung

des Ketten-Fadens" and PI. LVII in Pelliot "La trfl.me" are both in¬

complete : they lack the most essential part, the hook suspended at the

top of a bamboo pole through which the threads are passed and from

which the quüling process, normaUy called wei ^ or sui starts to take

place. "Die Herstellung des Ketten-Fadens" or "producing the warp- threads" is therefore a mistaken title.

The looms pictured in the Pelhot edition also differ from those shown

in Franke's edition''.

Ill

It is worth discussing in detaU the process known as "warping the

warp-reel". This operation is Ulustrated in Feanke'* Taf. XCVI, also

in Feanke Taf. XCIII (when it is wrongly labelled "spooling the sUk-

threads") and in Pelliot Pl. LVI, named "La chaine". Feanke simply calls the process "Die HersteUung des Kettenfadens".

First I wül give a short introduction to the problem : The preparation

of the warp-threads for the dressing of the loom began with the winding

of the threads around the pegs (ching-ya M 5P) of the warping-board

(ching-pa ^ |E) (Pig- 3) or around pegs in the ground." This was ne-

" See the illustrations of looms, especially investigated in : Dieteb Kuhn :

Die Darstellung des Handwebstuhls in Ghina. Eine Untersuchung zum Webstuhl

in der chinesischen landunrtschaftlichen Literatur vor dem 19. Jahrhundert.

Köln 1975, p. 72—85; Dieteb Kuhn: Die Webstühle des Tzu-jen i-chih aus

der Yüan-Zeit. Wiesbaden 1977. (Sinologica Coloniensia. Bd. 5.) See also the

drawloom pictmed on a painting dated to the Simg period in: Fang-chih

shih-hua |Ü fg. Peking 1978, pl. 6.

" Otto Feanke, op.cit. p. 136; annotations p. 180. The poem translated

by Fbanke refers to another working step. The poem of Lou Shou says

nothing on the technology of warping the beam. The picture is reproduced

with a vague inteipretation in Chaeles Singer, E. J. Holmyard (Ed.): A

history of technology. Oxford 1956, vol. 2, p. 210, Fig. 177 "Winding threads for the warp from cage-spools in a rack". There is no explanation how the reel actually worked.

'° The terms are from the Ts'an-sang ts'ui-pien, 1899, ch. 11, p. 44a with exception of "ching-pa" which is from the T'ien-kung k'ai-wu, 1637, oh. 1, p. 36 a.

Textile Technology in the King-chih-t'u 413

cessary to obtain a hank of even length and tension and a constant

number of threads. For this purpose the reels or cage-spools were placed

in two or more rows on a creel or rack. The threads were then drawn

through 'shppery eyes', passed on through the warping-reed, also caUed

rake (ching-p'ai ^ ij^)*", fastened at the pegs of the lease {chiao-tun ^

and finally wound around the pegs of the warping-board in a zigzag ar¬

rangement. The result was a hank. At this point the hank was taken from

the warphig-board, chained and then the threads passed over the rod of

another frame before being wound around the warping-reel which stood

at some distance away (Fig. 1). In the pictures of the Keng-chih-t'u we

can see a different way of winding the warp-threads: no warping-board

is used; instead the threads are wound directly from the spools on the

rack onto a reel. All the illustrations*' show clearly that this is not a

warp-beam, for unhke the warp-beam it has a reel structme**, whereas

the beaming of the warp-beam (sheng |^) is actually the final setting up

of the warp-threads in the loom (Fig. 2). The warping of the warping-

reeP* (ch'en t'ien-huo m\ Jl ^) on the reel-frame (yin-chia PP ^) with

which we are concerned here, is an intermediate process whereby the

threads were wound onto the warping-reel either from a hank or from

the cage-spools. There were two reasons why this intermediate process

might be necessary : either the thread was being prepared for a sectional

warping process (described below), or else it was going to be starched.

These are the points on which this discussion hinges. What differences

do we see between Pelliot's and Fbanke's illustrations ?

First, the bamboo rod of the creel (chitig-chia ^) in the Pelliot

edition has 'slippery eyes' (liu-yen f§ Oß), which were a type of ring.

Second, the threads are guided to the horizontal warping-reel by a worker

who makes them into a hank (ching-lii ^ ^) (Fig. 6). This difference

This term was used as early as 1264 in the Tzu-jen i-chih, ch. 18245,

p. 10 b in the Yung-lo ta-tien.

2' This working process can be seen in the T'ien-kung k'ai-wu (Fig. 5),

also in the Pin-feng kuang-i, ch. 3, p. Ila — 12a (Fig. 6); Ts'an-sang ts'ui- pien, ch. 11, p. 45 a — b. The illustration Fig. 5 is taken from a very carefully

printed T'ien-kung k'ai-wu edition of 1771, ch. 1, p. 24b. From the title of

this picture we can see that the starching work could also happen when beam¬

ing the warp-beam.

** This was also the case when cotton was used instead of silk. See e.g.

Shou-i kuang-hsün, 1808, ch. 2, p. 14b — 15a. The original source is the ikfien- hua-t'u, 1765, ill. no. XIII.

23 The warp-beam and the warping-reel are not identical in this article.

The warp-beam was placed in the loom, but the warping-reel had the shape

of a big reel and was used for arranging the warp-threads after winding and

before beaming. The term ch'en t'ien-huo is from the Pin-feng kuang-i, 1740,

ch. 3, p. lib—12a.

414 Deetbr Kuhn

is of some importance because it demonstrates that the pictmes do not

show an identical working process. To continue with the Pelliot il¬

lustration, we have no difficulty in explaining this warping-process as a

sectional one, that is, only a section of the final total number of warp-

threads is wound onto the warping-reel at a time.** The method apphed

uses a horizontal warping-reel, although the picture does not show the

pegs on the reel around which the hank is wound. Any starching work

must have taken place afterwards (Fig. 4).

We can suggest a shghtly different explanation for the Feanke il¬

lustrations (Fig. 5), and aU the later pictmes based on it. These illustra¬

tions show that another type of warping was apphed as early as the 14th

century*^ : this simpher warping method was usually used for starching ;

with a starch obtained from the gluten of wheat. This process was pre¬

paratory to the beaming of the warp-beam. Both methods shown in the

Keng-chih-t'u avoid the necessity of using the warping-board, and were

preferably applied when dressing small looms.

IV

In my opinion we have to accept that the warping-reel for sectional

warping as pictured in Pelliot was used in China as early as the 13th

century*" ; most probably it was limited to a few prefectures and under-

" We should this sectional winding method not confuse with the sectional

warp-beaming, where the warp-threads were directly wound aroimd the

warp-beam. Wo have no evidence that the Chinese used looms equipped with

sectional warp-beams before the 19th century. A. Schwarz published in the

Ciba Review 59 (August 1947), p. 2154—-2156 an article Warping frame and

warping reel in which he shows a picture labelled "Warping of silk in Japan

by means of warping spools and a simple reel (to tho right). After Hokusai

(1760—1849)". He explains: "It was ordy the work at the primitive ribbon- loom which needed such small quantities of yarn as to do away with the neces¬

sity for a special device for the preparation of the warp." It is one possibility to explain it but not very convincing because the threads do not form a hank

and furthermore a warp-beam generally was not employed when weaving

ribbons.

2° These pictures show small variations, but all had as their source the

lost Nung-shu edition of the year 1313, which had itself the Keng-chih-t'u of

the 13th century as original source for illustrations: Nung-shu (edition in 22 ch.), reprinted from tho Yung-lo ta-tien, 1407, ch. 21, p. 12b; Nung-shu (edi¬

tion in 36 ch.), 1530, ch. 24, p. 4a; Pien-min t'u-tsuan, 1593, ch. 1, p. 15a;

San-ts'ai t'u-hui, 1609, ch. 9, p. 34a; Nung-cheng ch'üan-shu, 1639, ch. 34, p.

10a—b; T'u-shu chi-ch'eng, 1726, k'ao-kung, ch. 218, ts'e 798, p. lb; Shou-

shih t'ung-k'ao, 1742, ch. 75, p. 15a.

*' The illustration in Pelliot's edition is of the year 1769 but based on

the Keng-chih-t'u edition of Ch'eng Ch'i of the 13th centmy.

Textile Technology in the King-chih-fu 415

stood only by a few workers. Surprisingly it did not develop into the verti¬

cal warping-reel as it was used in Europe in the 18th century. In the

summer of 1979 I had the opportunity to visit many silk factories in

China. I was very much surprised to see the horizontal warping-reel

described above at work, only altered by being power-driven. So we may

conclude that this type of warping was practised in China from the

13th century to our own days, although we lack pictorial evidence and

descriptions from Chinese sources of the 19th century.

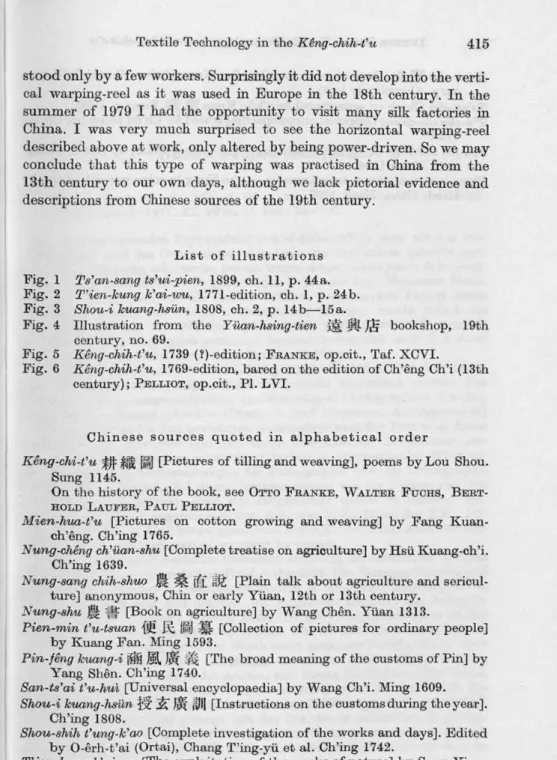

List of illustrations Fig. 1 Ts'an-sang ts'ui-pien, 1899, ch. 11, p. 44a.

Fig. 2 T'ien-kung k'ai-wu, 1771-edition, ch. 1, p. 24b.

Fig. 3 Shou-i kuang-hsün, 1808, ch. 2, p. 14b — 15a.

Fig. 4 Illustration from the Yüan-hsing-tien is Ä ^ bookshop, 19th

century, no. 69.

Fig. 5 Keng-chih-t'u, 1739 (?)-edition; Fbanke, op.cit., Taf XCVI.

Fig. 6 Keng-chih-t'u, 1769-edition, bared on the edition of Ch'eng Ch'i (13th century); Pelliot, op.cit., Pl. LVI.

Chinese sources quoted in alphabetical order

Keng-chi-t'u ^ ^ p] [Pictures of tilling and weaving], poems by Lou Shou.

Sung 1145.

On the history of the book, see Otto Fbanke, Walteb Fuchs, Bebt¬

hold Laufes, Paul Pelliot.

Mien-hua-t'u [Pictures on cotton growing and weaving] by Fang Kuan-

ch'eng. Ch'ing 1765.

Nung-cheng ch'üan-shu [Complete treatise on agricultme] by Hsü Kuang-ch'i.

Ch'mg 1639.

Nung-sang chih-shuo jft ^ ill llöi [Plain talk about agriculture and sericul¬

ture] anonymous. Chin or early Yüan, 12th or 13th oentury.

Nung-shu ^ ^ [Book on agriculture] by Wang Chen. Yüan 1313.

Pien-min t'u-tsuan ^ J.\- j^J ^ [Collection of pictures for ordinary people]

by Kuang Fan. Ming 1593.

Pin-feng kuang-i jSBj ]H, ft; [The broad meaning of the oustoms of Pin] by

Yang Shen. Ch'ing 1740.

San-ts'ai t'u-hui [Universal encyclopaedia] by Wang Ch'i. Ming 1609.

Shou-i kuang-hsün fj\\ [Instructions on the customs during the year].

Ch'mg 1808.

Shou-shih t'ung-k'ao [Complete investigation of the works and days]. Edited

by O-erh-t'ai (Ortai), Chang T'ing-yü et al. Ch'ing 1742.

T'ien-kung k'ai-wu [Tho exploitation of the works of nature] by Sung Ying-

hsmg. Ming 1637.

Ts'an-sang ts'ui-pien ^ ^ 3^ ü [Collection on sericultme] by Wei Chieh.

Ch'ing 1899.

29 ZDMG 130/2

416 Dieteb Kuhn, Textile Technology in the King-chih-t'u

Ta'an-shu ^ ^ [Book on sericulture] by Sun Kuang-hsien. Wu-tai, loth cen¬

tury. (Completely lost). i

Ts'an-shu [Book on sericulture] by Ch'in Kuan ^ Sung, c. 1090. |

T'u-shu chi-ch'eng [Imperial encyclopaedia] edited by Ch'en Meng-lei. Ch'ing 1726.

Tzu-jen i-chih A rjilj [Traditions of the joiners' craft] by Hsüeh Ching-

shih. Yüan 1264.

Yung-lo ta-tien (Great encyclopaedia of the Yung-lo reign-period] edited by

Hsieh Chrn. Ming 1407.

Bücherbesprechungen

RiCABDO A. Caminos : A Tale of Woe (Papyrus Pushkin 127). Oxford:

Griffith Institute 1977. XI, 99 S., 11 Taf 12.— £.

Zu dem bedeutenden Papyrusfund von el-Hiba (1890), dem wir u.a. den

,,Wenamun" und das Onomastikon des Amenope verdanken, gehörte auch

ein zwar vollständig erhaltener, jedoch wegen semer inhaltlichen Schwierig-

[ keiten lange imveröffentlicht gebliebener Text, der sog. Moskauer litera¬

rische Brief. Er kam wie die beiden anderen vorgenannten Papyri durch

W. GoLENiSHTSHBV ins Pushkiu Museum in Moskau, wurde jedoch im

Gegensatz zu jenen erst 70 Jahre später durch M. Kobostovtsev erstmals

der Wissenschaft zugänglich gemacht.' Seitdem haben sich auch S. Allam*

und G. Fecht* mit dem schwierigen Text beschäftigt.

Die hier besprochene Veröffentlichimg durch R. A. Caminos darf als in

jeder Hinsicht mustergültig und nahezu perfekt bezeichnet werden. Der

Papyrus wird in ausgezeichneten, großformatigen Photographien des Mu¬

seums imd in hioroglyphischer Umschrift (auf bequemen Ausklapptafeln)

vorgelegt. Mit der bei ihm gewohnten Genauigkeit wird der Text vom Autor

abschnittsweise übersetzt und mit einem ausführlichen Kommentar ver¬

sehen, der die zahlreichen schwierigen Stellen in überzeugender Weise er¬

klärt. Eingehende Untersuchimgen der Paläographie und der Orthographie

führen zu dem Schluß, daß dieser Papyrus ebenso wie die übrigen mit ihm

zusammen aufgefundenen etwa ein Jahrhundert später zu datieren sein

wird als man bisher angenommen hat, d.h. also in die Mitte der XXI. Dy¬

nastie und nicht in die Übergangszeit von der XX. zur XXI. Auch die aus¬

führlichen Indices verdienen es, erwähnt zu werden.

Der Text, dessen literarischer Charakter eindeutig heiwortritt, ist in Form

der Abschrift eines persönlichen Briefes abgefaßt. Die Eingangsformeln und

Segenswünsche an den Adressaten übertreffen an Ausführlichkeit bei weitem

das in Briefen dieser Zeit übliche. Im Folgenden schildert der heliopoli-

tanische Priester (jtj-ntr) Wr-m/j Selm des Hwy einem Schreiber in der

Residenz mit dem ramessidischen Namon Wsr-m/'t-R'-nhtw seine Schick¬

sale. Er ist, wie er sagt, schuldlos durch nicht genannte Feinde, die er auch

des Mordes und des Raubes bezichtigt, aus seinem Amt entfernt worden,

seine Angehörigen entführt oder getötet, sein Besitz konfisziert. Aller Mittel,

auch seines Schiffes und seines Wagens beraubt, ist er zu Fuß durch das

Land geirrt, zuerst durchs Delta, dann durch Oberägypten, und endlich

sogar in die Große Oase gelangt. Ob der Ort, wo er schließlich in größter

Not und Armut lebt, in dieser Oase lag, wie Caminos annimmt, ist zweifel¬

haft; nach 4,4 scheint er am Nil zu liegen, so daß er doch vielleicht eher im

' M.A. KoRosTOVTSEv : HepaTHMecKHü FlanHpyc 127 h3 coSpaHUH FMHH hm.

A. C. riyuiKHHa. Moskau 1961.

« In: JEA 61 (1975), S. 147—53.

» In: ZÄS 87 (1962), 12—31.

29*

Zeitschritt der Deutschen Morgeniändischen Gesellschaft Band 130, Heft 2 (1980) Q Deutscbe Morgenländische Gesellschaft e.V.