The Magical Quality of Trees in a Deforested Country

Von Silvia Freiin Ebner von Eschenbach, Würzburg

In China almost all virgin forests were cut down centuries ago, except in

certain peripheral areas of Northeast and Southwest China and Tibet where

minority people still preserve their natural forests. But even there, most of

the virgin forests were destroyed as soon as the Chinese entered the region.

If a conservation of forests was practiced at all, the foremost policy was to

reduce deforestation and not to encourage reforestation. State support was

limited to the selective planting of trees considered useful for intensive ag¬

riculture rather than for extensive forestry, a practice unheard of in China.

Trees were also planted as a protection for roads and highways, for strategic

reasons and as a natural barrier against floods. In scholarly gardens their use

was a purely esthetic one, as may be seen in numerous paintings.'

In 1930 W.G. LowDERMiLK commented on the denuded North China

Plain, with a few scattered nurseries amidst the agricultural area:

"It is true that no forests are to be found in this plain, but each village has its trees, which are grown according to a system. Nurseries dating back to ancient times are still in existence to supply seedlings and cuttings for planting."^

One might think that Chinese civilization is quite indifferent towards tree

planting. Yet, since ancient times trees were considered sacred or sacrosanct,

and were preserved as single old and big trees or in groves around temples

and shrines. How to explain the apparent discrepancy between Chinese tree-

veneration and their casual attitude towards forest preservation? As Wolf¬

ram Eberhard and Yu Chien emphasize, the tree cults of the present do

not necessarily stem from ancient cults, but may be connected with them in

some aspects.^

' Daniels/Menzies 1996, pp. 658-662; Schäfer 1962, pp. 291, 300; Tuan 1970,

pp. 34-35, referring to Richardson 1966, pp. 151-153. For scholarly garden cuhure in

China v. inter alia Clunas 1996, pass, and FIarrist 1998, pp. 46-66.

2 Lowdermilk/Li 1930, p. 137b.

' Eberhard 1970, p. 23; Yu 1997, chap. 1, p. 4, 6, chap. 9, p. 2.

Trees as Residence of the Earth God

The idea that long-lived trees are inhabited by a spirit or deity of nature may

have stood at the beginning of tree worship and is still witnessed today. On

his travels through the provinces of Shandong, Henan, Shanxi and Shenxi

in 1907, Edouard Chavannes observed big trees overladen with ribbons

of red cloth bearing the names of their devotees written in black characters.

Still today houses in country villages are often built around a tree as their

center. In 1927 during his field survey in the Ding county of the Province

of Hebei, Sidney Gamble witnessed people hanging cloth scrolls on trees.

In the years 1924, 1925, and 1935 when he traveled in the province of Si¬

chuan, David Graham noticed the worship of old trees, such as cedars, ban¬

yans (ficus retusa), cypresses or pines. In Hongkong in the early 1950s, Ru¬

dolphe Burkhardt observed old trees that were lavishly decorated. On

his field trip in 1934-1935, Eberhard described the veneration of camphor

trees and their worship as Earth Gods, a phenomenon peculiar to the prov¬

ince of Zhejiang which is still preserved to this day. Florian C. Reiter

describes extensively the adoration of an old tree that he witnessed on his

stay in the province of Sichuan in 1989. In the years 1992-1994, Yu Chien

carried out field research on tree cults in Taiwan."*

According to Eberhard, the tree cult is a special form of the cult of the

Earth God.^ Our knowledge of the Earth God (Tu i) dates back to bone

inscriptions of the Shang Dynasty (16'''-1P'' cent. bc). As a god of nature,

the Earth God was held responsible for rain, flood, wind and the harvest.

As early as the Zhou Dynasty (1045-221 bc) and the Han Dynasty (206 bc

to ad 220), trees were considered as markers of sacred places.* As we know

from the Baihu tong [The Comprehensive Discussions in the White Tiger

Hall], trees made it possible for people to see a sacred place from afar. Fur¬

thermore, trees showed the presence of the respective god residing there:

"Why is there a tree on the altar of the Gods of the Earth and of the Millet?

That it may [thereby] be honored and recognized. [Thus] people may see it

from afar and worship it."''

■* Photography of a sacred tree in Shanxi province (Chavannes 1909, fig. no. 1159);

Chavannes 1910, p. 471; Gamble 1954, pp. 412-413; Graham 1961, pp. 113-114; Graham 1936, pp. 59-61 and Burkhardt 1953-58, vol. 1, p. 122, vol. 2, p. 119,151, quoted after Yu 1997, chap. 2, pp. 5, 8; Eberhard 1968, pp. 174-175; Eberhard 1970, pp. 21-22 with fig. 1 on p. 22; Reiter 1992, pass.; Yu 1997, chap. 3 et pass.

* Eberhard 1968, p. 174.

' Berger 1980, p. 88.

^ Ban Gu (ad 32-92), Baihu tong (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 1994),;. 3, p. 89, line 14 (translation from Tjan 1949-52, vol. 2, p. 384); Berger 1980, p. 89.

During the Zhou Dynasty, the single Earth God (Tu) of the Shang seems

to have been replaced by a plurality of gods of the soil (she ^i) with their re¬

spective territories. * The Earth God came to be organized according to the hi¬

erarchy of human groupings and terrhorial administration.^ In the Chunqiu

period (770-476 bc) every chy state had hs own Earth God.'° Later on, even

each quarter of the city and each village in the country, each field and grave

adored hs own genius loci}^ During the dynasties of the Song (960-1279),

Ming (1368-1644), and Qing (1644-1911), the cuh of the Earth God became

more and more an integral part of the local hierarchies, defying control by the

central administration of the state.'^ Kanai Noriyuki makes a distinction

between the formalized official cult practiced at the imperial, provincial and

district levels and the archaic cult still found in village communities.'^

Ideally, four trees were to be planted on four sides of a square used as an

imperial altar for the Earth God. Four regional altars stood in the center of

the four divisions of the imperial territory. The Shang shu tells us what kind

of tree may be used: for the great altar with a single tree one should plant

a pine tree (song ^ü). On the altar with the four directional trees, a thuja or

cypress (bo ;tä) should stand for the Earth God of the east, a catalpa (zi #)

for the Earth God of the south, a chestnut tree (li ^) for the Earth God of

the west and an sophora (huai for the Earth God of the north.'"*

Each altar consisted of a mound or an artificial heap of earth with the

respective tree planted on top. Without an altar, a natural grove (cong ^)

or a very huge tree served the purpose. It was believed that the largest tree

amidst or in the near surroundings of a village was the place where the local

Earth God resided. Chavannes assumes that originally the Earth God was

thought to be identical with a grove of trees. As he points out, it seems quite

convincing that the artificially planted single tree evolved from the natural

grove and that in the course of time veneration of a grove was reduced to

veneration of one single tree during the Han Dynasty.'^

8 Chang 1970, pp. 192-193, 195.

' Chavannes 1910, pp. 437-450.

'° Chang 1970, p. 195.

" Lagerwey 1991, p. 26.

'2 For the organization of the cuh of the Earth God during the Song, Ming, and Qing Dynasties v. Dean \998, pass., focusing on Fujian province.

•3 Kanai quoted in Dean 1998, p. 20 with note 3.

" Shang shu, Yipian as quoted in Baihu tong (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 1994),;'. 3, p. 90, hnes 8-9 (translated in Tjan 1949-52, vol. 2, p. 385); Sullivan 1962, p. 169, cp. p. 174.

'5 J^ozi jiangu (Zhuzi]kheng-ed.), j. 8, "Minggui",p. 146, hne 8 (translated in Schmidt- Glintzer 1992, pp. 185); Chavannes 1910, pp. 467, 470-473, 475-476, cp. p. 437; Granet 1922 (1975), pp. 77-78; Granet 1929 (1985), p. 102; Sullivan 1962, p. 169; Müller 1979, p. 140-141, 181, referring to Zhou U, "Dasi tu" (translated in Biot 1851, vol. 1, p. 193).

According to the Huangdi zhaijing [YeUow Emperor's Site Classic], grass

and trees were seen as the earth's hair.'* A tree was therefore a symbol of the

Earth God's vital energy {qi Trees condensed the God's chthonic ener¬

gies into a personalized form. The Baihu tong says that the reason why the

Earth God's altar (she) has no roof, is because the tree should stay in con¬

tact with the vital energy (qi) of heaven and earth.''' By ad 500 the tree cult

as a symbol of the Earth God seemed to have been so neglected that a peti¬

tioner handed in a memorandum to remind the Emperor that trees ought to

be planted on the altars for the Earth God.'^ This complaint recurs often

among Song Neo-Confucians who like Hu Bingwen X. (1250-1333)

and Liu Kezhuang fJ ^ ^± (1187-1269) pleaded that people should return

to the ways of the ancients and plant a tree upon the Earth God's mound

instead of building a shrine with a roof on top of the altar."

According to Chavannes, the Earth God was also represented (xiang

as a statue (zhu i), originally made of clay (tu ouren i 1^ A), stone or

wood and later on exclusively of stone. The Earth God was thought to take

residence in this statue.'^" Eduard Erkes follows Chavannes' idea propos¬

ing that the statue itself had developed from the tree.^' According to the Zuo

zhuan [Tradition of Master Zuo], the Earth God's statue (she) was carried

by a priest accompanying a military campaign.^^ From texts telling that "the

ruler took the Earth God (she) with him in his arm" and that "on military

campaigns the Earth God (she) was transported on a war chariot", Clau¬

dius Müller concludes that the Earth God (she) may have manifested him¬

self in a wooden stele or stone slab.^-* This custom was paralleled by carrying

the corpse of a king or a wooden statue representing the dead king into the

battlefield, as the corpse or statue was believed to contain vital energy that

ensured a victory.^''

Huangdi zhaijing (Yimen guangdu, ed. in: Baibu congshu),;. A [=;. 19], p. 7b [= p. 50b]

(translated in Bennet 1978, p. 13).

Baihu tong (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 1994),;. 3, p. 89, line 12.

Memorial of Liu Fang, in: Wei shu (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 1974),;. 55, pp. 1225-1226.

" Dean 1998, p. 25-26, referring to Hu Bingwen (1250-1333), Yunfeng wenji, j. 2 and to Liu Kezhuang (1187-1269), Houcun xiansheng daquan ji,]. 93 as quoted in Kanai 1992, pp. 188-189, resp. Kanai 1982, p. 353.

2° Wang Chong (27-ca. 100), Lunheng [Discourses Weighed in the Balance] (Zhuzi

jicheng-ed.), "Jiechu", p. 246, lines 9, 15-16 (translated in Forke 1907, vol. 1, p. 536); Du You, Tongdian [Comprehensive Institutes] (Guoxue jiben congshu-ed.) (801),;. 45, pp. 261,

lines 13-14; Chavannes 1910, pp. 476-477; cp. Müller 1979, pp. 181-182.

2' Erkes 1928, p. 11.

22 Zuo zhuan. Lord Ding, year 4 (507 bc) (Legge 1872 (1960), p. 750, line 1, p. 754a).

2' Müller 1979, p. 271, note 1, does however not quote the source of his citation. Cp.

Granet 1922 (1975), p. 80; cp. Granet 1929 (1985), p. 104.

In later times, the statue {zhu i) representing the living image (xiang) of

the God residing in it may have been reduced to a simple tablet (also called

zhu i). Kanai proved that shamanic practices were common from the

Tang Dynasty (618-907) onwards and human-like images of the Earth God

were widely used during the Song Dynasty. Ritual purists among the Song

Neo-Confucians like Liu Kezhuang (1187-1269) complained of the anthro-

pomorphization of the Earth God.'^^ The Song Neo-Confucian Hu Bing¬

wen (1250-1333) remarks:

"Nowadays, in the she akars of

the common people, they usu¬

ally paint things inside the room

of a house. [...] They paint an

old white-haired man with long

eyebrows, and reverently refer to

him as the Duke of the She Ahar

of the Soil (Shegong 7i ^). More¬

over, they provide him with an

old wife. All this is absolutely

not in accordance with the an¬

cient ways.

According to a local gazetteer from

the Fujian province, it was still

common during the Ming Dy¬

nasty to carry statutes of the Earth

God (shezhu Jl) around in a

procession.-^'' Nowadays the Earth

God is venerated as an old man

(called Tudigong i 14 in South¬

ern China, resp. Tudi laoye i i4

^ in Northern China). In ur¬

ban quarters he is housed in small

temples. But in the countryside he

is still represented by a stone on a

Fig. 1: Tree representing the Earth God in

an urban quarter of the 20''' century China,

photography (Lagerwey 1991,

fig. 20 onp. 30)

Shiji (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1959),;'. 4, p. 120, line 5 (translated in Chavannes 1895-1905, vol. 1, p. 224); cp. Erkes 1928, p. 8 with a discussion in note 19; cp. Erkes 1931, p. 63.

" Dean 1998, p. 20 with note 3, p. 25, referring to Liu Kezhuang (1187-1269), Houcun xiansheng daquan ji,j. 93 as quoted in Kanai 1982, p. 353.

" Hu Bingwen (1250-1333), Yunfeng wenji, j. 2 (translation after Dean 1998, pp. 25-26 as quoted in Kanai 1992, pp. 188-189).

2^ Dean 1998, p. 34, quotes from [Hongzhi] Xinghua fuzhi,j. 15, "Fengsu".

Square altar surrounded by trees, the square having the archaic shape of the earth [fig. 1].^^

The idea and the ritual of animating the anthropomorphic image (xiang)

of a god (shen) is paralleled by the representation of an ancestor's soul (also

called shen) as a statue (zhu i) or tablet (also called zhu Jl.), inscribed with

the ancestor's name. Originally the ancestral tablet (shenzhu # i) seen as

the permanent residence of the ancestor's soul was a human-shaped statue

of the ancestor. Ancestral images (xiang, also called ying fS) made of clay or

wood were common during the Song Dynasty. Ancestral statues continued

to be used in some parts of China until recent times. In the Fujian province

ancestral images were still in use as late as the 17''' century. Again, Song Neo-

Confucian fundamentalists propagated what they believed were the ideals

of the ancients and pleaded for steles (zhu i) or boards (ban

One may, however, take into consideration a hypothesis about the origin

of the zhu i postulated by Hayashi Minao. According to Hayashi, the

prototype of the zhu i is to be found in neolithic Liangzhu jade cylindri¬

cal objects (cong 3$). He believes that neolithic jade cylinders were origi¬

nally not called cong but zhu i ("hosts") in the sense of the meaning

to invite the gods or ancestral souls to take residence in a jade cylinder as

their lodging place [fig. 2]. With the beginning of the Zhou dynasty, a zhu

i was made of wood as it says in the Gongyang commentary to the Chun¬

qiu [Spring and Autumn Annals]. The Guliang commentary to the Chun-

28 Mazo 1988, pp. 60b-61b; Chavannes 1909, fig. no. 1159.

2' Lunbeng (Zhuzi jicheng-ed.), "Jiechu", p. 246, hnes 14-15 (translated in Forke 1907, vol. 1, p. 536); "Luzhou zhongjian Bao Ma er gong citang ji" [Report on the Reconstruc¬

tion ofthe Sacrificial Hall for the Mr. Bao and Mr. Ma in Luzhou District] (1182), in: Han Yuanji (1118-87), Nanjian jiayi gao (Congshu jicheng chubian-ed.), "ji" [Notes], /. 15, p. 299, lines 6-8; Zhou Hui (1126-after 1198) Qingbo zazhi (Congshu jicheng chubian- ed.) (1192).;. 12, p. 107, hne 5; Hong Mai (1123-1202), Yijian zhi (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 1981),;. 7, "Zhou fumian"[Noodle-seller Zhou], p. 1358, line 2; Wu Zimu, Meng- liang lu (Congshu jicheng chubian-ed.),;'. 15, "Lidai gumu" [Old Tombs of all Epochs], p. 137, line 15; Cheng Yi (1033-1107), Henan Cheng shi wenji, in: Er Cheng ji (Beijing:

Zhonghua shuju 1981),;. 10, "Zuo zhu shi" [Model Formular for Making a Stele], p. 627, line 3 and ;'. 18, p. 241, lines 13-14 (all texts translated in Ebner von Eschenbach 1995a, pp. 190-191, resp. p. 288, p. 312, pp. 317-318, p. 376, p. 397); Sima Guang (1019-86), Sima shi shuyi (Congshu jicheng chubian-ed.),;'. 10, "sangyi" [Mourning Rites], art. 6, " ji" [Sac¬

rifices], p. 115, line 8-10, p. 121, lines 1, 2 (translated in Yu 1981, p. 80); Sima Guang (1019-86), Sima Wenzhang gong chuanjiaji (Guoxue jiben congshu),;'. 79, "Hedong jiedu shi shou taiwei kaifu yitong sansi Lu guo gong Wen gong xianmiao bei" [Stele on the altar for the ancestors of the Duke of Lu, Mr. Wen, Acting Military Governor of Hedong,

Commander Unequaled in Honor], p. 975, line 8; Erkes 1931, p. 63-64; Croissant 1990,

pp. 243-245; Ebrey 1991, p. 62. For a detailed description of the ritual of reviving the zhu V. Laufer 1913 (1976), pp. 113-115 [= pp. 529-531]), resp. pp. 115-116 [= pp. 531-532]);

Ebner von Eschenbach 1995a, pp. 46, 49-50,119-120.

qiu says: "As for the zhu, it is what

the spirits rely on. Its form is four¬

square, with a hollowed-out center

which may be reached on all four

sides. [...]." Hayashi therefore sug¬

gests that during the Han Dynasty

the Altar of the Earth God was a

square platform with a circular aper¬

ture in the center.^"

The neolithic jade cylinders {cong

^) are engraved with masks or else

with a man wearing a mask, probably

a tattooed shaman. The headgear of

such a mask was interpreted as a

plume of feathers.^' Hayashi, how¬

ever, shows that there are also masks

with a tree rising from the top of the

mask and interprets the mask as the

head of the god residing in the cylin¬

der. Tree masks may be recognized

on a rubbing of a stamped tile from a

Han tomb at Zhengzhou in the Henan

province or on the rubbings of eaves

tiles of the Zhanguo period (475-221

bc) from Biyang in the Henan prov¬

ince. As a consequence of Hayashi's

reasoning, Alexander Soper asks: "[...] may it not have been possible that

there was also some neolithic equivalent of the later central tree, perhaps a cer¬

emonial bunch of grasses inserted into the central channel [of the cong J,t]?"

This hypothesis is corroborated by the fact that many cong are wider at the

top and at the bottom than they are inside the cylinder, like a vase.'^

The altar of the Earth God was the place from which any demonstration

of power started and ended. From Zhou times onwards, the highest Earth

Fig. 2: Neolithic jade cong of the

Liangzhu culture (ca. 3000 bc), 10 cm

high, 8,4, resp. 6,6 cm in diameter, 1986

excavated from tomb M12:97 at

Fanshan in the district of Yuhang in

Zhejiang, Archaeological Institute of

the province of Zhejiang (drawing

based on Anonymous 1990, fig. 56).

'° Chunqiu Gongyang zhuan (Shisan jing zhushu-ed.), Lord Wen year 2 (624 bc),

p. 4918B, line 2 (translated in Legge 1872 [1960], p. 233b); Chunqiu GuUang zhuan (Shisan jing zhushu-ed.), Lord Wen year 2 (624 bc), p. 5216B, line 13a-b (translated by Soper in Hayashi 1990, p. 7); Hayashi 1990, pp. 6-8,10.

" Ebner von Eschenbach 1995b, pp. 139,141.142. For a discussion of form and func¬

tion of shamanic masks v. Ebner von Eschenbach 1995b, pa«.

52 Hayashi 1990, pp. 12/21 with fig. 16 on p. 18 and figs. 23a-b on p. 20; Soper in Hayashi 1990, pp. 21-22.

God was symbol for the State and was consulted conceming its affairs, es¬

peciaUy before and after a military campaign. As late as in the Ming State

ritual, it was at the Earth God's altar that oaths were taken. It was the place

where the feudal lords held great assemblies and imposed punishments and

where wars against animals or humans, i.e. hunting expeditions and military

campaigns started. Hunters sacrificed their game at the altar. War prisoners

and political opponents were presented at the Earth God's altar and some¬

times sacrificed there. The Earth God was the only god to be offered noth¬

ing but raw meat {xueshi jfe ^) and whose statue or tablet was smeared with

blood. Marcel Granet suggests that, originally, trophies of the victims

were hung on the Earth God's tablet. Kanai thinks that the north Chinese

cults of the Earth God were affiliated with the cult of the dead, while in the

southern cults the Earth God was associated with health and prosperity.

Trees of Life and Renewal

Archeological evidence shows that trees were even placed inside the tomb on top

of the inner coffin. A bamboo tree which was still green at the time of excavation

was found in a Chu tomb of the Zhanguo period at Mashan in Jiangling.^'' The

first figural representations of trees are found on Late Zhou bronze mirrors as

well as on other archaeological objects such as bricks and roof tiles.'^ Artificial

trees made of bronze or ceramic, most of them with a mount-like base were

excavated from Han Dynasty tombs in Northwest and Southwest China.

Among the artificial trees taken from tombs the bronze ones hung with

Han Dynasty wuzhu-coins are the most predominant. People obviously

" Zho zhuan. Lord Zhuang year 6 (687 bc), Lord Xuan year 15 (593 bc). Lord Cheng

year 13 (577 bc), Lord Xiang year 13 (559 bc), Lord Zhao year 13 (528 bc) (Legge 1872

[1960], p. 78, lines 16-17 with p. 79b, p. 326, line 2 with p. 328a, p. 379, line 9 with p. 381b, p. 456, line 13 with p. 458a, p. 644, hne 6 with p. 650a); Lewis 1990, p. 17, 23, also quotes from Zhou li zhengyi (Shanghai: Zhonghua shuju 1934),;. 36, pp. 13b-15a, ;. 45, p. Ila; Chunqiu Guliang zhuan zhushu (Shisan jing zhushu-ed.). Lord Zhuang year 8, ch. 5, pp. lla-b, Lijijijie (Shanghai, Shangwu yinshuguan 1936),;. 3, p. 83,;'. 5, pp. 78-79, Tai gong liutao zhijie (in: Mingben wujing qi shu zhijie, vols. 1-2, Taibei: Si Di Jiaoyu 1972),

;'. 1, pp. 63b-67a; Guoyu [Discourses on the States] (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe 1978), ;'. 6, "Qi", p. 223, lines 13-14; Mozi jiangu (Zhuzi jicheng-ei/.), ;'. 8, "Minggui", p. 146, hnes 4-5, p. 149, lines 14-15 (translated in Schmidt-Glintzer 1992, pp. 185,188);

Granet 1922 (1975), pp. 79, 80; Granet 1929 (1985), p. 104; Granet 1929 (1985), p. 126;

Erkes 1939-40, pp. 191-193; Müller 1979, pp. 110-111. For more detail v. Chang 1970,

pp. 195-196; Dean 1998, p. 22; Kanai as referred to in Dean 1998, p. 20-21 wkh note 3.

Erickson 1994, p. 31 with fig. 63 on p. Ill, quotes from Jiangling Mashan yi hao Chumu (Beijing: "Wenwu chubanshe 1985), p. 10, fig. 12.

" De Silva 1964 (1980), p. 45.

believed that the coins would confer prosper¬

ity and wealth to them and that they would

grow again after they had been shaken. FIa-

yashi had his own theory about the meaning

of the wuzhu-coins. The wuzhu-coins being of

trifling value, he believes that the word wuzhu

i ^ is a mere pun for the term wushou -§• ^

("my longevity"), similar to the providential

phrase inscribed in Han bronze mirrors "May

your longevity be like metal or stone".^*

A money tree base from Xinjin in Sichuan

shows people carrying poles across their shoul¬

ders hung with wuzhu-coins. Money tree bases

from Pengshan and Santai in the Sichuan prov¬

ince show people taking coins off trees where

coins are arranged in a way inspired from the

molds for casting coins.Their mount-like base

reminds of the lid of the Western Han Dynasty

(206 BC-AD 8) boshan /w-censers (tf ih ;^).^^

One example for the money tree of the East¬

ern Han Dynasty (ad 25-220) is a bronze tree

standing on a clay mountain-like pedestal, 105

centimeters high. It was excavated from a rock

tomb in Pengshan district in the Sichuan prov¬

ince in 1972 [fig. 3]. Peter Wiedehage as¬

sumes that coins were hung on the branches

of the tree as an offering to the spirit or god

inhabiting the tree. And indeed, the "Queen

Mother of the West" (Xiwangmu © i #) is

seated in the branches and on its pedestal,

granting immortality.^' Birds can also be found

perching on the branches or in the crown of the

money tree. Susan Erickson interprets them

Fig. 3: Bronze money tree (yaoqian sbu) with a ceramic base of the Eastern Han

Dynasty (ad 25-220), 105 cm high, 1972 excavated

in the district of Pengshan

in Sichuan, Museum of the

province of Sichuan

(drawing based on Wiede¬

hage 1995, fig. on p. 367).

" Hayashi 1990, p. 11-12.

Erickson 1994, p. 14 with fig, 17b on p. 64, quotes Anonymous 1959, pl. 43. For

more detail v. Erickson 1994, p. 14, fig. 8a on p. 54 and fig. 19 on p. 66, quotes Nanjing bowuguan 1991, p. 36, fig. 45, Anonymoüs 1976, p. 395. For a mold for casting coins v.

Swann 1950, pl. 8.

Erickson 1994, p. 16-17; Wang 1987, figs. 1-2 on p. 91; Tang / Guo 1983, figs. 8-11 on p. 33. For more detail on mountain censers v. Erickson 1992, pp. 6-28.

" Wiedehage 1995, p. 365a.

as supernatural fenghuang-phoenixes (ÄLJE) or luan-h'irds (%), auspicious

omens as they are described in the Shanhai jing [Classic of the Mountains

and Rivers] of the Han period.''" Hayashi concludes from the fact that some

of them hold a pearl in their beak presenting it to a person kneeling in front

of it that the birds have descended from heaven to convey longevity in the

sense of immortality, as the pearl (zhu S^) probably was thought of as a pun

for cinnabar (zhu the elixir for achieving long life.'"

Yet, there are no Han literary sources describing the usage for the money

trees. It is only from a Qing Dynasty description of the New Year's Festival

(Yanjing suishiji) that we know about the custom of shaking coins from so-

called "money trees" {qianshu i\ ^If) or "trees from which one can shake

money" {yaoqian shu ii, In the description it says: "Take a big twig

of the pine or the cypress, stick it into a vase and hang old copper coins, gold

or silver money on it [...].'""

Eastern Han money trees seem to stem from cosmic world trees of the

Shang Dynasty. Fragments of bronze trees from the Shang Dynasty were

excavated in 1986 in Sanxingdui near Guanghan which belongs to the dis¬

trict of Pengshan district in the province of Sichuan. As far as the trees could

be reconstructed, they were found to have had a height of about 1 to 4,2

meters with a mountain-like base. Erickson and also Zhao Dianzeng sug¬

gest that they were intended as passage ways from earth to heaven as axis

mundi tied between the mundane and the spiritual world, the ascent of the

tree leading to immortality. This concept corresponds to the tree seen as an

axis mundi, as it was analyzed by Mircea Eliade who takes a comparative

intercultural view.''''

In the opinion of Eberhard, the tree cult as part of the cult for the Earth

God is a fertility cult.''^ The idea that the sacred tree in China symbolized a

divine phallus was first introduced by Bernhard Karlgren and restated

by Erkes."** Karlgren's interpretation was criticized as an exaggeration by

^° Erickson 1994, pp. 22-23 with fig. 1 on p. 47 and fig. 29 on p. 76; Anonymous 1962, fig. 6.1 on p. 398; Xiong 1979, fig. 15.9 on p. 30; He 1991, fig. 29.2 on p. 17 and fig. 30.2 on p. 18; Shanhai jing, "Xishan jing" (translated in Cheng/Pai Cheng/Thern 1985, p. 24).

"" Hayashi 1990, p. 11.

Erickson 1994, p. 7; Wiedehage 1995, p. 368a-b.

*^ Du Lichen (1855-1911), Yanjing suishiji [Annual Customs of Beijing] (Beijing: Guiji chubanshe 1983), p. 97 (translation after Wiedehage 1995, p. 368b).

Wiedehage 1995, p. 366b; Erickson 1994, p. 27; Zhao 1995, pp. 125b-126b with

fig. on p. 125a. The excavators called the trees shenshu ("trees of the soul /ancestor").

For the tree as axis mundi v. Eliade 1951 (1980), pp. 259-263.

Eberhard 1968, p. 174.

Karlgren mQ,pass.; Erkes 1931, p. 65.

Müller in his study of the ahar of the Earth God. In Müller's opinion

the phallic element in the cult of the Earth God is absolutely secondary and

unimportant.'*''

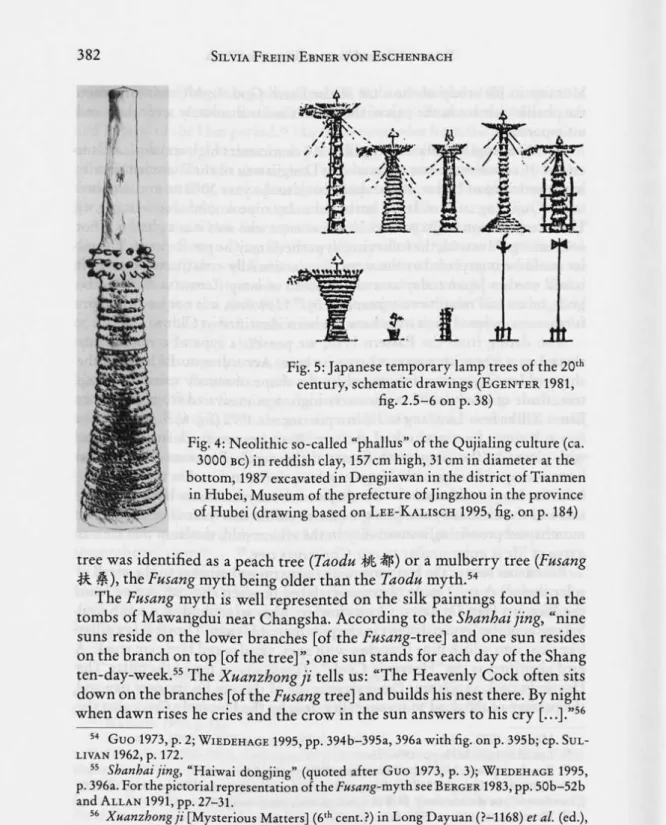

In 1987 a lengthy hollow clay pillar 157 centimeters high and with a diam¬

eter of 31 centimeters was excavated in Dengjiawan of the Tianmen district

in the province of fiubei. It was dated back to the year 3000 bc and ascribed

to the Qujialing culture. It has burls and a clay rope wound around it [fig. 4].

The interpretation by Jeonghee Lee-Kalisch who sees it as a phallus is not

convincing.''^ Instead, the following hypothesis may be put forward. The pil¬

lar could be interpreted as the stem of an artificially constructed tree, as it

is still used in Japan today as a sacred torch or lamp {taimatsu ^'i: to be

built, burnt and rebuilt every year [fig. 5].''^ fiowever, it is not known if any

further examples of such trees have yet been identified in China.

Also dating from the Eastern Han, we possess a type of ceramic lamp

shaped as a tree with a mountain as its base. According to Erickson, the

shape of lamp trees was influenced by the shape of money trees.^° A lamp

tree, made of ceramic, 92 centimeters high, was excavated from a tomb in

Jianxi Xilihe near Luoyang in Henan province in 1972 [fig. 6].^' A pillar acts

as a substitute for the trunk of the tree. Branches are stuck into the pillar

with plate-like flat lamps with flames at their ends. Blossoms, cicadas and

human-shaped beings with wings perch on the branches. On top of the pil¬

lar a flat lamp can be seen in the shape of the mythical sun bird. With the

sun and the cicadas symbolizing a rebirth in the new year after the winter

months and promising immortality in the after world, the lamp tree seen as

a tree of life is quite similar to our Christmas tree.'^

Erickson relates the lamp tree with lights on its branches to the myth of

solar trees.A tree, made of ceramic glazed in green and red, dating from

the Western Han Dynasty, 63 centimeters high was found in a tomb near

Sijiangou of the Jiyuan district in the province of Henan. The stem is a pillar¬

like axis, into which nine branches with apes, cicadas and birds are stuck. A

bird identified as the "Heavenly Cock" (Tianji) sits on top of the pillar. The

Heavenly cock announces the reappearance of the sun on the new day and

the passage of the dead to immortality. It is by the Heavenly Cock that the

Müller 1979, p. 62.

*^ Lee-Kalisch 1995, pp. 183-185.

For the Japanese tree cuh v. Egenter 1981, pp. 34-54.

" Erickson 1994, p. 29. The excavators called the lamp trees lianshu deng i4 Ä S („tree lamps") or duozhi deng ^ S („lamps whh many twigs").

5' Wiedehage 1995, p. 394a-b.

" Sullivan 1962, p. 173.

" Erickson 1994, p. 28.

Fig. 5: Japanese temporary lamp trees of the 20'''

century, schematic drawings (Egenter 1981,

fig. 2.5-6 on p. 38)

Fig. 4: Neolithic so-called "phallus" of the Qujialing culture (ca.

3000 bc) in reddish clay, 157cm high, 31 cm in diameter at the

bottom, 1987 excavated in Dengjiawan in the district of Tianmen

in Hubei, Museum of the prefecture of Jingzhou in the province

of Hubei (drawing based on Lee-Kalisch 1995, fig. on p. 184)

tree was idemified as a peach tree (Taodu ^) or a mulberry tree {Fusang

•i^ ^), the Fusang myth being older than the Taodu myth.^"*

The Fusang myth is well represented on the silk paintings found in the

tombs of Mawangdui near Changsha. According to the Shanhai jing, "nine

suns reside on the lower branches [of the Fusang-txte] and one sun resides

on the branch on top [of the tree] ", one sun stands for each day of the Shang

ten-day-week.^' The Xuanzhong ji tells us: "The Heavenly Cock often sits

down on the branches [of the Fusang tree] and builds his nest there. By night

when dawn rises he cries and the crow in the sun answers to his cry [...]."'*

'■I Guo 1973, p. 2; Wiedehage 1995, pp. 394b-395a, 396a with fig. on p. 395b; cp. Sul¬

livan 1962, p. 172.

5' Shanhai jing, "Haiwai dongjing" (quoted after Guo 1973, p. 3); Wiedehage 1995, p. 396a. For the pictorial representation of the Fusang-myth see Berger 1983, pp. 50b-52b and Allan 1991, pp. 27-31.

Xuanzhong ji [Mysterious Matters] (6'*' cent.?) in Long Dayuan (?-1168) et al. (ed.),

Guyu tubu [Catalogue with Drawings of Ancient Gems], quoted after Guo 1973, p. 2

(translated in Wiedehage 1995, p. 396a).

A lamp tree with ten branches has the three-legged crow as the sun bird on each of its candle holders.^''

As a sun tree, the Fusang tree is a felicitous plant that indicates the waxing

of the moon thus serving as a monthly calendar (mingjie ^ jC), e.g. a lamp

tree with symmetrically arranged branches. The arrangement may be three-

dimensional around a central axis or two-dimensional in two parallel rows.

An example for a parallel arrangement of the branches of the Fusang-tree is

found in a relief in the tombs of the Wu Family near Jiaxiang in the province

of Shandong.^^ The periodic growth and maturity of seed capsules on a ficti¬

tious monthly plant was described in the Lunheng [Discourses Weighed in

the Balance].^' In later texts the Fusang tree is suggested to be a mulberry

tree with two trunks supporting each other, similar to trees growing to¬

gether (mulianli ^ ii S).*°

Souls dwelling in trees may also take on the shape of the birds living there.

E.g., pine trees harbor birds, especially cranes. Even phoenixes perch on the

boughs, as white rabbhs hop around the roots.*' According to the Xijing

zaji [Miscellaneous Notes from the Western Capital] of the Han Dynasty

"[...] there was an old pine, to which tradition ascribed an age of more than a

thousand years, and into which white cranes flew continuously"."

Trees of Death and Longevhy as Habkat of the Ancestral Souls

The Earth God rules the underworld and is lord of the subterranean water

arteries transporting vital energy for agriculture. As the Earth God is held

responsible for fertility and prosperity, the dead are entrusted to this God.

When buried in the God's realm under the earth, the dead have the chance of

conferring fertility and prosperity onto the living members of their family.

Any soil deeper than three chi A, i.e. 75 centimeters belongs to the

Earth God's realm. As an apology and an insurance, land for digging graves

57 Allen 1950, fig. 17 (p. 139), p. 140; Croissant 1964, p. 144.

58 Croissant 1964, p. 144, referring to Chavannes 1909, fig. no. 116; Berger 1980,

p. 284, note 107, referring to Chavannes 1909, fig. no. 85.

5' Lunheng (Zhuzi jicheng-et/.), "Shiying", p. 172, line 9-p. 173, line 10 (translated in Forke 1907, vol. 2, pp. 317-321).

Berger 1980, p. 81, 281, note 116, referring to Chavannes 1909, fig. no. 91; cp. a

rubbing of a stone engraving in Chengxian in Gansu Province (Chavannes 1909, fig.

no. 168).

^' De Groot 1892-1910, vol. 4, part 2, p. 289; de Groot 1892-1910, vol. 2, p. 464,

quotes from Chuxue ji.

" Xijing zaji in Tushu jicheng, sect. "Caomu" [Plants],;'. 201, p. 29C, lines 10-11 (trans¬

lation from de Groot 1892-1910, vol. 4, part 2, p. 289).

Fig. 6: Ceramic lamp tree of the late Eastern Han period (2"'' century ad) painted in red and black color on white, 92 cm high with a pedestal of

40cm in diameter, 1972 excavated in

Jianxi Xilihe near Luoyang in Henan

by the working team for cultural relics of Luoyang in the province of

Henan (drawing based on

Wiedehage 1995, fig. on p. 393)

has to be "bought" from the Earth god.

As early as the Han Dynasty it was be¬

lieved that the region of a grave extended

from heaven to the lower reaches of the

earth." Even today the Earth God's

presence is still required when the soil

is touched, for example when building a

house or digging a grave. Then his per¬

mission is asked for in a ceremony called

"ground-breaking" {potuK^ti.).'''^

After the dead is buried and the

grave is closed, until this day the tree is

the preferred plant to place on a grave

tumulus. It is also important to note

that even today the ancestors' shrine

for the dead of any village is built next

to the tree of the Earth God in the cen¬

tral area of the village. Therefore, any

mound with a sacred tree planted on

top of it may be interpreted as belong¬

ing to the realm of the dead.*^

It was presumed that the custom of

marking a tomb by a tumulus was intro¬

duced to China by the Western Zhou

Dynasty (1045-771 bc) from Siberia.**

Late Zhou bronze mirrors already show

trees in combination with a hill.*'' The

Sanli tu [Drawings of the Three Forms

of Rites], originally dating from the

Eastern Han Dynasty, contains an illus¬

tration of grave mounds with trees on

top or beside the mound [fig. 7].*^ If

trees were used as grave markers in the

" Kleeman 1984, p. 14; Asm 1994, pp. 311-312, quotes from Jin Dynasty Jiang shi jiazhuan. For more detail on deeds for buying land for graves v. Kleeman 1984, pass, and Asim 1994, pass.

'■^ Yu 1997, chap. 3, p. 5.

" Lagerwey 1991, p. 26-27 wkh fig. 17 on p. 27.

'"^ Kuhn 1995a, p. 48b, Kuhn 1995b, p. 213.

" De Silva 1964 (1980), p. 45; for the pre-Han v. fig. 8 on p. 46 and for the ensuing development v. figs. 9-11 on p. 46.

Zhou and Han Dynasties, the species of the tree chosen depended on the rank

of the deceased.*^ According to the Baihu tong "a tumulus is made and trees

are planted [on the grave] that h may be recognized [as such]."''° Ching an

apocryphal book of rites, the Baihu tong continues saying:

"The grave-mound of the Son of Heaven is thirty feet high with a pine-tree planted on it; that of a Feudal Lord is half that height with a cypress planted on it; that of a great officer eight feet high with a luan-tree {%) [...] planted on it; that of a common officer four feet with a sophora planted on it; the common man has no grave-mound, but a willow is planted [on the grave]."^'

The size of the grave mound and the number of trees increased with the rank

of the dead/^

Trees planted on or near a tomb also served the very practical purpose of

protecting the grave from robbers by assimilating it with the surrounding

area. Thus the tomb of Chinggis Qan remained undiscovered.''^ This may

also have been true for the tomb of Shihuangdi (reigned 221-210 bc) of the

Qin Dynasty as his grave mound was made to look like a hill.'"'

A tree planted on a grave mound may take up the soul of the dead person

buried underneath. The tree becomes a residence for the soul and is animated

by it. Trees are planted on a grave to strengthen the soul of the dead person.

The idea is that if the soul is strengthened, the body will be saved from

corruption. Pine, cypress, mulberry, catalpa or other trees could be planted

on grave mounds as well. They harbor a lot of vital energy (qi) to pass onto

the soul of the dead person that would otherwise be deemed to lose its vital en¬

ergy. It was thought that the vital energy contained in trees would protect the

dead body from decay and prevent it from dissolving. Thus, trees stabilize the

soul by living on the energetic substance (qi) of the interred body.^^ This idea

Nie Chongyi (Song Dynasty) (ed.), [Xincheng zhengshi jiashu chongjiao] Sanli tu

(Sibu congkan xinbian-ed.),;. 19, p. 5 a.

<>' Berger 1980, p. 88.

7° Baihu tong (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 1994), ;. 11, p. 559, lines 5 (translation from Tjan 1949-52, vol. 2, p. 651).

7' Hanwenjia, quoted in Baihu tong (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 1994),;. 11, p. 559, hnes 6-7 (translated after Tjan 1949-52, vol. 2, p. 651); cp. Zhou li, ch. 21, 1. 44 (de Groot 1892-1910, vol. 2, p. 461); cp. Lijt, "Wangzhi", art. no. 3, §2 (Couvreur 1913 (1950), vol. 1, parti, p. 287).

" DeGroot 1892-1910,vo1. 2,p. 461.

73 Boyle 1974, p. 10.

7" De Groot 1892-1910, vol. 2, pp. 401, 460.

" Chao Buzhi (1053-1110),yj7e ji (Sibu congkan-ed.),;. 60, "Ba Qizhou xianying fen- huang gaoji wen" [Prayer and Funeral Adress on yellow paper to be burnt at the Tomb of my Late Father who had retired [from his office] in Qizhou], pp. 7b-8a; Wang Shipeng (1112-1171), Kuaijisanfu [Three /«-poems of Kuaiji] (Huhai lou zhi congshu, ed. in: Baibu

Fig. 7: Trees on grave mounds in a

graveyard, Song Dynasty woodcut dating

from tfie Eastern Han Dynasty (ad

25-220) Sanli tu (ed. in Nie Chongyi [Song Dynasty], [Xincheng zhengshi jiashu chongjiao] Sanli tu [Sibu congkan

xinbian-ed.], j. 19, p. 5a)

is also to be found among the altaic

peoples, especially the Mongols.''*

Thus grave trees came to be iden¬

tified with the souls of the dead.

The souls of the dead somehow re¬

sided in the branches and foliage of

their grave trees. Trees were sensi¬

tive to the mourners' grief. Tears

shed at the grave changed the trees'

color. The well-being of the dead

depended on the living members of

the family looking after the grave

tree. If the dead were well cared

for, the family of the living was

prosperous as well. This is why the

branches and foliage were not only

an indicator of the well-being of

the dead buried underneath, but

also of the living. If the living did

not care for their dead, their own

well-being was endangered. If a

branch was lost, this meant a lack

of care and the ensuing death of a

member of the family. If the whole

tree fell to decay, the family was

destined to become extinct.''''

congshu) (1158), "Shi Fang mu zhemu" [The Silkworm tree at the Tomb of Shi Fang] p. 23;

Baoqing Kuaiji xuzhi [Continuation of the Local Gazetteer of Kuaiji in the Baoqing Era]

(Song Yuan difang zhi congshu-ed.) (1225),;'. 7, "Xinchang Shi shi fen" [The Tomb of the Shi Family in Xinchang District], p. 6a-b [= p. 6614] (all texts translated in Ebner von Eschenbach 1995a, pp. 197-198,267-269); de Groot 1892-1910, vol. 2, pp. 462-463,468, vol. 4, part 2, pp. 276-277, 287; Stein 1987 (1990), p. 104; Reiter 1992, p. 153; Ebner von Eschenbach 1995a, p. 175. For the subtle relationship between the so-called "soul" and the body of the dead v. Ebner von Eschenbach 1995a, pp. 113-137.

7' Roux 1963, p. 139, Bartold 1970, pp. 209-210.

77 "Wang Yin, Jin shu as quoted in Ouyang Xun (557-641), Yiwen leiju [Compendium of Art and Literature] (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe 1965), ;'. 88, "Mu" [Trees], p. 1515, lines 4-5; Minggong shupan qingming ji [Clear and Bright Compilation of Judg¬

ments by Bright Judges] (Beijing: Zhonghua-shuju 1987), "Mai mumu" [Selling Grave Trees], pp. 333-334; "Wang Shipeng (1112-1171), Kuaiji sanfu [Three /«-poems of Kuaiji]

(Huhai lou zhi congshu, ed. in: Baibu congshu) (1158), "Shi Fang mu zhemu" [The Silk¬

worm Tree at the Tomb of Shi Fang] p. 23; Baoqing Kuaiji xuzhi [Continuation of the

One third of the tributes and taxes paid to the Han Emperors was

spent on the building of their respective mausoleums. Building commenced

one year after enthronement and trees were always planted on the grave

mound."Planting or sowing pines and cypresses with one's own hand"

[shou zhi/zhong song bo ^ ^ 46) became a topos of Confucian filial

piety {xiao On tombs of man and wife "intertwining or embracing

stems or branches of twin trees" were likewise a topos for conjugal devo¬

tion.^° However, tomb trees were cut down completely with the intention of

eliminating the dead and their offspring. This happened, for example, on the

eve of the Qing Dynasty when Empress Dowager Cixi became suspicious

of an ominous gingko tree growing on the tomb of Prince Chun (Yihuan),

grandfather of the later Xuantong Emperor, and had the tree cut down.^'

Spirits that take trees as their habitat, are souls (shen) with a human body

of blood living in the tree. If the tree is cut down or burnt, the resident

soul of the tree bleeds and utters cries of pain with a human voice.^^ The

Xuanzhong ji tells us that "the sap of a tree a hundred years old is red like

blood." The Han philosopher Ge Hong in his work Bao Puzi says: "The

deepest roots of cypresses a thousand years old have the shape of puppets in

a sitting posture, seven inches high. When incisions are made therein, they

lose blood [...]."*' If somebody is going to cut down the tree growing on the

ancestral tomb of his family for the purpose of selling the timber, he is sure

to meet his ancestors in his dreams giving him a warning as for example:

"We have lived (zhu i) in this tree for three hundred and eighty years [...].

What makes you think you can cut us down whenever you feel like h?"^"* Or

Local Gazetteer of Kuaiji in the Baoqing Era] (Song Yuan difang zhi congshu-ed.) (1225), j. 7, "Xinchang Shi shi fen" [The Tomb of the Shi Family in Xinchang District], p. 6a-b [= p. 6614] (all texts translated in Ebner von Eschenbach 1995a, pp. 226-229, 267-269);

Reiter 1992, pp. 153-154; Ebner von Eschenbach 1995a, p. 175.

7« }in sbu, (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 1974),;. 60, p. 1651, lines 12-14; Poo 1990, p. 40.

7' For textual examples v. de Groot 1892-1920, pp. 464-467.

*° For textual examples v. de Groot 1892-1920, pp. 467, 471-472.

Pu 1975, pp. 20-21. The character for bo ("whhe") as part of the character for "ginko tree" was thought to be an omen as it would combine with the character wang ("prince") and form huang ("emperor"), i.e, the next emperor was to be an offspring of Prince Chun - it actually was - and not empress dowager Cixi herself, anxious to gain power.

" De Groot 1892-1910, vol. 4, part 2, p. 274.

" Ge Hong (ca. 280-340), Baopuzi [Book of the Preservation-of-Solidarity Master]

(Zhuzi jicheng-ed.), Neipian [Inner Chapters],;'. 11, "Xianyao", p. 46 , lines 16-17 (trans¬

lated in DE Groot 1892-1910, vol. 4, part 2, p. 287).

Hong Mai (1123-1202), Yijian zhi (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 1981),;. 6, "Chen mu shanshu" [The pine tree on the tomb of the Chen family], p. 585, lines 14-15 (translated in Daniels/Menzies 1996, p. 631).

eise, if not completely unrooted, the tree grows up again in its old place and

thrives once more due to the power of its spiritual energy (qi).^^

However, long-lived and big trees that contain a large amount of "old es¬

sences" {gujing 4i. ^) are preferred for this purpose. As they are thought to

be no longer useful for profane purposes they do not run the risk of being

cut down for fuel or timber.** From ancient times onwards, rules were set up

to protect trees from being cut. In order to save the forests in former times

grass and bushes rather than trees were used as fuel for cooking. This is con¬

firmed by the fact that, as Menzies remarks, the words used for fuel were xin

W( and rao ^, their characters being written with the radical for grass and

not for wood.*^ In the 3'^'' century ad, we already find rules against arson

in forests. According to the Tang lü shuyi [Code of the Tang Dynasty with

Commentary], anyone who intentionally or unintentionally "caused fire"

{shi huo fi in the forests was to be punished. From the Tang Code up to

the Qing Code heavy penalties were laid upon any person who accidentally

set fire in the groves around the imperial mausolea and other sacred sites.

The stealing of trees from the area of the imperial tumuli as well as theft

of trees from anybody else's ancestral tombs was severely punished. The

Tang Code records that stealing trees from within the imperial tomb pre¬

cincts was to be punished with two and a half years' banishment, theft of

trees from other people's graves with one hundred strokes. From a Song

collection of law cases we learn that it was not allowed to cut down grave

trees and sell them. Besides being illegal, in Song times the selling of grave

trees was considered as an act of inhumanity {huren ^ f— ) and disrespect of

filial piety {huxiao ^ ;^). According to the Qing Code, stealing trees from

ordinary tombs was to be punished with one hundred strokes and cangue

for one month. If the number of trees stolen exceeded 21 military exile to the

frontier was to follow a beating of one hundred strokes.*'

85 Guoyu [Discourses on the States] as quoted in Ouyang Xun (557-641), Yiwen leiju

[Compendium of Art and Literature] (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe 1965), 88,

"Mu" [Trees], p. 1507, hne 10; Chavannes 1910, p. 470; Reiter 1992, p. 156.

8' Stein 1987 (1990), pp. 96-97,103-104.

87 Daniels/Menzies 1996, p. 656.

88 Tang lii shuyi (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1983),;'. 27, "Zalü" [Miscellaneous laws], art.

no. 428, " Yu shanling zhaojing nei shihuo" [Setting Fires within the Precincts of the Impe¬

rial Mausolea], p. 508; Schäfer 1962, pp. 298-299; Linck 1992, p. 117; Jones 1994, p. 357, translation of article 382 ("Accidental Setting Fires") from the Qing Code.

8' Tang lii shuyi (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 1983), ;. 19, "Zeidao" [Theft and Robbery], art. no. 278, "Dao yuanhng nei caomu" [Theft of Plants and Tress from the Imperial Parks and Mausolea], p. 355; Minggong shupan qingming ji [Clear and Bright Compilation of Judg¬

ments by Bright Judges] (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 1987), "Shemu yu seng" [Giving Trees as Alms to a Buddhist Monk], p. 330, lines 8-9, "Chongzhen guan nü daoshi lun juefen" [The

Conclusion

A worship of trees can be observed from earliest archeological objects and

textual sources up until our times. Evidence is scarce, but not insufficient.

Veneration of trees is closely linked to the Earth God cult and the cult of the

ancestral souls, as the Earth God is thought to be present in trees as well as

in the ancestral souls of those buried in the earth underneath them in the

Earth God's realm. Trees erected on the altar of the Earth God and trees

planted on ancestral grave mounds were both found to be similar manifesta¬

tions of the vital energy (qi) of a god or soul (both called shen). Trees as habi¬

tats for the Earth God or the souls were considered a visible link between

heaven and earth in the sense of an axis mundi.

Thus making the god's or souls' vital energy visible led to the anthropomor-

phization of their respective trees as they evolved into pillars (zhu jL) with en¬

gravings and then into images (xiang). In sphe of Neo-Confucian attempts to

reverse this trend, human-shaped representations of the Earth God and of an¬

cestral souls are still witnessed today. Yet, anthropomorphic images did not lead

to the complete abandonment of trees which are still venerated today, especially

in the countryside. Like their human-shaped counterparts, trees are believed to

be living beings that contain human blood and speak with a human voice.

If trees are properly cared for, the ancestors' family flourishes. If they are

damaged or even cut down, they suffer and the respective ancestors' family

becomes extinct. This may be the reason why in earliest times trees were

buried with the dead inside the tomb. Various types of trees were created

artificially for that reason. It is beyond doubt that artificial trees, hung with

coins or equipped with lamps, served as a guarantee for the prosperity of the

ancestral souls and their descendants. Trees are an essential link between the

dead and the living, i.e. death and life. Death means life, i.e. immortality and

fertility of the family. But trees were cut down or planted for other reasons

as well, above all according to rationality and usefulness.

In conclusion, we may underline the fact that in China there are very con¬

tradictory attitudes concerning the treatment of the tree: On the one hand,

it is venerated as the visible form of vital energy of the Earth God and ances¬

tral souls but on the other hand nothing is done to prevent the tree's exploita¬

tion for its material value. These contradictions can hardly be reconciled.

Daoist Priestess of the Chongzhen Temple was Accused of Digging up Graves], p. 583, lines 14-15, "Mai mumu" [Selhng Grave Trees], p. 333, hnes 10-11, 14, p. 334, lines 2-3, "Zhudian zheng mudi" [Landowner and Tenant quarrel over Grave Land], p. 325, line 5 (all texts trans¬

lated in Ebner von Eschenbach 1995a, pp. 217, 227-229, 230); Boulais 1924, §7, articles 1047,1049-1050 on pp. 476-477; Jones 1994, p. 242, translation of article 263 ("Stealing Trees from the Emperors' Tombs") from the Qing Code; Ebner von Eschenbach 1995a, p. 109.

Bibliography

Allan, Sarah: The Shape of the Turtle. Myth, art, and Cosmos in Early China.

New York 1991.

Allen, Maude Rex: "Early Chinese Lamps." In: Oriental Art 2,4 (Spring 1950), pp. 133-140.

Anonymous: Sichuan Han dai diaosu yishu. Beijing: Zhongguo gudian yishu

chubanshe 1959.

—: "Yunnan Zhaotong Guijiayuanzi Dong Han mu fajue." In: Kaogu 1962/8,

pp. 395-399.

Anonymous: "Sichuan Santai xian faxian Dong Han mu." In: Kaogu 1976/6, p. 395.

Anonymous: Liangzhu wenhuayuqi. S. I. Wenwu chubanshe, Liangmu chubanshe

1990.

Asim, Ina: "Status Symbol and Insurance Policy: Song Land Deeds for the Afterlife."

In: Dieter Kuhn (ed.): Burial in Song China. Heidelberg 1994 (Würzburger

Sinologische Sehriften), pp. 307-370.

Barthold, V.V./Rogers, J.M.: "The Burial Rhes of the Turks and the Mongols."

In: CAJ 14 (1970), pp. 195-227.

Rennet, Steven J.: "Patterns of the Sky and Earth: A Chinese Science of Applied Cosmology." In: Chinese Science 3 (1978), pp. 1-26.

Berger, Patricia Ann: Rites and Festivities in the Art of Eastern Han China:

Shantung and Kiangsu Provinces. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 1980.

—: "Purhy and Pollution in Han Art." In: Archives of Asian Art 36 (1983), pp. 40-58.

Biot, Feu Edouard: Le Tcheou-li ou Rites des Tcheou. 3 vols., Paris 1851.

Boulais, Guy, S.J., Manuel du Code chinois [Da Qing lüli bianlan]. Shanghai 1924

(Varietes Sinologiques. 55.).

Boyle, John Andrew: "The Thirteenth-Century Mongols' Conception of the

After Life: The Evidence of Their Funerary Practices." In: Mongolian Studies.

Journal of the Mongolia Society 1 (1974), pp. 5-14.

Burkhardt, Valentine Rudolphe: Chinese Creeds & Customs. 3 vols. Hong

Kong 1953-58.

Chang Tsung-tung: Der Kult der Shang-Dynastie im Spiegel der Orakelinschriften.

Eine paläographische Studie zur Religion im archaischen China. Wiesbaden 1970

(Veröffentlichungen des Ostasiatischen Seminars der Johann-Wolfgang-Goethe- Universität, Frankfurt/Main).

Chavannes, Edouard: Les memoires historiques de Se-ma Ts'ien. 6 vols. Paris

1895-1905.

—: Mission Archeologique dans la Chine Septentrionale. Paris 1909. (Publication de

rficole Fran9aise d'Extreme Orient).

—: "Appendice: Le Dieu du Sol dans la Chine antique." In: Le T'ai Chan. Essai de monographie d'un culte chinois. Paris 1910, pp. 437-525.

Cheng, Hsiao-Chieh/Pai Cheng, Hui-Chen/Thern, Kenneth Lawrence:

Shanhaijing: Legendary Geography and Wonders of Ancient China. Taipei 1985.

Clunas, Craig: Fruitful Sites. Garden Culture in Ming Dynasty China. London 1996 (Envisioning Asia).

Couvreur, S., S.J.: Li Ki, ou Memoires sur les bienseances et les ceremonies. 1 vols.

Ho-chien fu 1913 [reprinted Leiden 1950].

Croissant, Doris: "Funktion und Wanddekor der Opferschreine von Wu Liang

Tz'u. Typologische und ikonographisehe Untersuchungen." In: Monumenta

Serica 23 (1964), pp. 88-162.

—: "Der unsterbliche Leib: Ahneneffigies und Reliquienporträt in der Porträtplastik

Chinas und Japans." In: Martin Kraatz/Jürg Meyer zur Capellen/

Dietrich Seckel (ed.): Das Bdd in der Kunst des Orients. Stuttgart 1990.

(AKM. 50/1.), pp. 235-268.

Daniels/Menzies 1996 = Joseph Needham: Science and Civilisation in China. Vol.

6: Biology and Biological Technology. Part III: Agro-Industries and Forestry.

Christian Daniels: Agro-Industries: Sugarcane Technology. I Nicholas K.

Menzies: Forestry. Cambridge 1996.

DE Groot, J.J.M.: Tbe Religious System of China. Its Ancient Forms, Evolution,

History and Present Aspect. Manners, Customs and Social Institutions Con¬

nected Therewith. 6 vols. Leiden 1892-1910.

Dean, Kenneth: "Transformation of the She (Ahar of the Soil) in Fujian." In:

Cahiers d'Extreme-Asie 10 (1998), pp. 19-75.

Eberhard, Wolfram: Tbe Local Cultures of South and East China. Leiden 1968.

—: "Essays on the Folklore of Chekiang, China." In: id: Studies in Chinese

Folklore and Related Essays. Bloomington, Indiana 1970 (Indiana Univershy

Folklore Instkute Monograph Series. 23.), pp. 17-144. [Translated and revised

publication of the original paper "Zur Volkskunde von Chekiang." In: Zeit¬

schrift für Ethnologie 67 (1936), pp. 248-265].

Ebner von Eschenbach 1995a = Silvia Freiin Ebner von Eschenbach: Die

Sorge der Lebenden um die Toten. Thanatopraxis und Thanatologie in der

Song-Zeit (960-1279). Heidelberg 1995 (Würzburger Sinologische Schrihen).

— 1995b = Silvia Freiin Ebner von Eschenbach: "Tierische Heroen and hero¬

ische Tiere in der chinesischen Kultur." In: Georges-Bloch-Jahrbuch des Kunst- geschichtlichen Seminars der Universität Zürich, 2 (1995), pp. 127-144.

Ebrey, Patricia B.: Confueianism and Family Rituals in Imperial China. A Social

History of Writing About Rites. Prineeton, New Jersey 1991.

Egenter, Nold: "Die heiligen Bäume um Goshonai. Ein bauethnologischer Bei¬

trag zum Thema Baumkult." In: AS 35 (1981), pp. 34-54.

Eliade, Mircea: Schamanismus und archaische Ekstasetechnik. Frankfurt a.M.

^1980 [First published under the titel Le chamanisme et les techniques archai¬

ques de l'extase. Paris 1951].

Erickson, Susan N.: "Boshanlu-Mountain Censers of the Western Han Period: A

Typological and Iconological Analysis." In: Archives of Asian Art 45 (1992), pp. 6-28.

—: "Money Trees of the Eastern Han Dynasty." In: The Museum of Far Eastern

Antiquities 66 (1994), pp. 6-115.

Erkes, Eduard: "Idols in Pre-Buddhist China." In: Artibus Astae 1 (1928), pp. 4-12.

—: "Some Remarks on Karlgren's 'Fecundity Symbols in Ancient China'." In:

Bulletin of tbe Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 3 (1931), pp. 63-68.

-: "The God of Death in Ancient China." In: TP 35 (1939-40), pp. 185-210.

Forke, Alfred: Lun-beng. Miscellaneous Essays of Wang Cb'ung. 2 vols. Shanghai/

London/Leipzig 1907.

Gamble, Sidney D. [Research Secretary of the Chinese National Association of the

Mass Education Movement]: Ting Hsien: A Nortb China Rural Community.

New York 1954.

Graham, David Crockett: "Tree Gods in Szechwan Province." In: Journal of tbe West China Border Research 8 (1936), pp. 59-61.

— •.Folk Religion in Southwest China. Washington 1961 (Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 42/2.).

Granet, Marcel: Tbe Religion of the Chinese People. Translated, edited and with

an Introduction by Maurice Freedman. Oxford 1975 [first published under the

titel La religion des Chinois. Paris 1922].

—: Die chinesische Zivilisation. Familie, GeseUschaft, Herrschaft. Von den Anfängen bis zur Kaiserzeit. Frankfurt a.M. 1985 (Suhrkamp Taschenbuch Wissenschaft.

518.) [first published under the titel La civilisation chinoise. Paris 1929].

Guo Moruo: "Taodu, Nüwa, Jialing." In: Wenwu 1973.1, pp. 2-6.

Harrist, Robert E.: Painting andprivate life in eleventh-century cbina: Mountain

villa by Li Gonglin. Princeton, New Jersey 1998.

Hayashi Minao: "On the Chinese Neolithic Jade Tsung/Cong. Abridged and

Adapted by Alexander C. Soper." In: Artibus Asiae 50/1-2 (1990), pp. 5-22.

He Zhiguo: "Sichuan, Mianyang, Hejiashan, M2 Dong Han yamu qingli jianbao."

In: Wenwu 1991/3, pp. 9-19.

Jones, William C: The Great Qing Code. Oxford 1994.

Kanai Noriyuki: "Sodai no sonsha to sozoku." In: Rekishi ni okeru minsbü

to bunka. Sakai Tadao sensei koki shukuga kinen ronshü. Tokyo: Kokusho

kankökai 1982.

—: "Nanso ni okeru shashokudan to shabyo ni tsuite ki no shinko otoshite chüshin."

In: Fukui Fumimasa (ed.): Taiwan no shükyö to Chugoku bunka. Tokyo:

Fukyosha 1992.

Karlgren, Bernhard: "Some Fecundity Symbols in Ancient China." In: Bulletin

ofthe Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 2 (1930), pp. 1-67.

Kleeman, Terry P.: "Land contracts and Related documents." In: Chugoku no

shükyö shisö to kagaku. Makio Ryökai Hakase Shöju kinen ronshü. Tokyo 1984.

—: "Mountain Deities in China: the Domestication of the Mountain Gods and the

Subjugation of the Margins." In: JAOS 114 (1994), pp. 226-238.

Kohn, Livia: Review of Lagerwey 1991, in: Monumenta Serica 45 (1997), pp. 455-457.

Kuhn 1995a = Dieter Kuhn: "Totenritual und Beerdigungen im chinesischen Alter¬

tum." In: Kulturstiftung Ruhr, Essen (ed.): Das Alte China. Menschen und Göt¬

ter im Reich der Mitte 5000 v. Chr.-220 n. Chr. München 1995 [Catalogue of an

exhibkion at Villa Hügel, Essen, 2"'' June 1995-5''' November 1995], pp. 45-67.

— 1995b = Dieter Kuhn: "Tod und Beerdigung im chinesischen Akertum im

Spiegel von Rkuakexten und archäologischen Funden." In: Tribus 44 (1995),

pp. 208-267.

Lagerwey, John: Der Kontinent der Geister. Cbina im Spiegel des Taoismus. Eine

Reise nacb Innen. Oiten 1991 [first published under the title Le Continent des

esprits. La Chine dans le miroir du taoisme. Bruxelles 1991].

Laufer, Berthold: "The Development of Ancestral Images in Ancient China." In:

Journal of Religious Psychology 6 (1913), pp. 111-123 [reprinted in: Hartmut

Walravens (ed.): Kleinere Schriften von Berthold Laufer. Vol. 2, Publikationen

aus der Zeit von 1911-1925. Part 1. Wiesbaden 1976 (Sinologica Coloniensis.

Ostasiatische Bekräge der Universkät zu Köln. 7.), pp. 527-539].

Lee-Kalisch, Jeonghee: cat. no. 8 "Phallus." In: Kulturstiftung Ruhr, Essen (ed.):

Das Alte China. Menschen und Götter im Reich der Mitte 5000 v. Chr.-220

n. Chr München 1995 [Catalogue of an exhibkion at Villa Hügel, Essen, 2"^

June 1995-5''' November 1995], pp. 183-185.

Legge, James: The Chinese Classics. Vol. 2. The Works of Mencius. Hongkong/

London 1861 [reprint Hongkong I960].

—: The Chinese Classics. Vol. 5. The Ch'un Ts'ew with the Tso Chuen. Hongkong/

London 1872 [reprint Hongkong I960].

Lewis, Mark Edward: Sanctioned Violence in Early China. Albany 1990.

Linck, Gudula: "Über den Umgang mit dem Feuer im vormodernen China und

was sich dahinter verbirgt. Unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Sung- und

Ming-Zek." In: Oriens Extremus 35 (1992), pp. 107-158.

Lowdermilk, W.C. /Li T.L: "Forestry in Denuded China." In: The Annals of the

American Academy of Political and Social Science 152 (1930), pp. 127-141.

Mazo, Ramön Lay: "T'u-Ti Shen - Gods of the Earth." In: Review of Culture 5

(1988), pp. 60-64.

Müller, Claudius C: Untersuchungen zum "Erdaltar" she im China der Chou-

und Han-Zeit. München 1979 (Münchner Ethnologische Abhandlungen. 1.)

Nanjing bowuguan (ed.): Siehuan Pengshan Han dai yamu. Beijing: Wenwu

chubanshe 1991.

Poo, Mu-CHOu: "Ideas conceming Death and Burial in Pre-han and Han China."

In: AM, 3. Ser., 3/2 (1990), pp. 25-62.

Pu Yi: Ich war Kaiser von China. Vom Himmelssohn zum Neuen Menschen.

Die Autobiographie des letzten chinesischen Kaisers Pu Yi (1906-1967). Frank¬

furt a.M. 1975 [translated into German by Mulan Lehner and Richard

Schirach].

Reiter, Florian C: "Notices conceming an old cypress at Mt. Ch'i-ch'ü in

Szechwan (China)." In: ZDMG 142 (1992), pp. 149-158.

Richardson, D.: Forestry in Communist China. Bakimore 1966.

Roux, Jean-Paul: La mort chez les peuples aitaiques anciens et medievaux d'apres

les doeuments ecrits. Paris 1963.

Schafer, Edward H.: "The Conservation of Nature under the T'ang Dynasty." In:

Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 5 (1962), pp. 279-308.

Schmidt-Glintzer, Helwig: Mo ti. Von der Liebe des Himmels zu den Menseben.

Aus dem Chinesischen übersetzt und herausgegeben von Helwig Schmidt-

Glintzer. München 1992 (Diederichs Gelbe Reihe. 94, China.).

DE Silva, Anil: Cbinesiscbe Landschaftsmalerei am Beispiel der Höhlen von Tun¬

huang. Baden-Baden 1964, ^1965.

Stein, Rolf A.: Tbe World in Miniature. Container Gardens and Dwellings in Far

Eastern Religious Thought. Stanford, California 1990 [first published under

the title Le monde en petit: jardins en miniature et habitations dans lapensee

religieuse d' Extreme Orient. Flammarion 1987].

Sullivan, Michael: The Birth of Landscape Painting in Cbina. London 1962.

Swann, Nancy Lee: Food and Money in Ancient Cbina: The Earliest Economic

History of China to A.D. 25 - Han Shu 24 with related texts, Han Shu. 91 and

Shih-Cbi 129. Prineeton 1950.

Tang Jinyu/Guo Qinghua: "Shaanxi Mianxian Hongmiao Dong Han mu qingli

jianbao." In: Kaogu yu wenwu 1983/4, p. 3034.

Tjan Tjoe Som: Po Hu T'ung. The Comprehensive Discussions in the White Tiger

Hall. 2 vols. Leiden 1949-1952.

Tuan Yi-Fu: Cbina. London 1970 (The World's Landscapes).

Wang Shouzhi: "Chenggu chutu de Han dai taodu." In: Wenbo 1987/6, pp. 91-92.

Wiedehage, Peter: cat. no. 86, "'Geldschüttelbaum' (yaoqianshu) mit Sockel", cat.

no. 98, "Einhundert-Blumen-Leuchter (baibuadeng)" , cat. no. 99, "Mythischer

Baum ('Taodushu')." In: Kulturstiftung Ruhr, Essen (ed.): Das Alte China.

Menschen und Götter im Reich der Mitte 5000 v. Chr.-220 n. Chr München

1995 [Catalogue of an exhibkion at Villa Hügel, Essen, 2"^ June 1995-5'''

November 1995], pp. 365-368, 392-393, 393-397.

Xiong Shuifu: "Guizhou Xingyi Xingren Han mu." In: Wenwu 1979/5, pp. 20-35.

Yu, Clara: "Ancestral Rites." In: Patricia Buckley Ebrey (ed.): Chinese CiviUza¬

tion and Society. A Sourcebook. New York/London 1981, pp. 79-83.

Yu, Chien: Three Types of Chinese Deities - Stone, Tree, and Land. Ph. D. Diss.

Lancaster University 1997 [electronic version].

Zhao Dianzeng: "Mktler zwisehen Himmel und Erde: Die Funde von Sanxingdui."

In: Kulturstiftung Ruhr, Essen (ed.): Das Alte China. Menschen und Götter im

Reich der Mitte 5000 v. Chr.-220 n. Chr München 1995 [Catalogue of an exhibi¬

tion at Villa Hügel, Essen, 2"'' June 1995-5''' November 1995], pp. 115-129.

Robert Deutsch/AndrI Lemaire: Bihlieal Period Personal Seals in the Shlomo Moussaieff Collection. Tel Aviv: Archaeological Center Publications 2000. 228 S. ISBN 965-90240-5-3.

Schon mehrfach wurden Objekte aus der Sammlung Moussaieff publiziert. Das geschah

an recht unterschiedlichen Stellen und ließ nicht erkennen, welche Schätze in dieser Sammlung vereint sind. Die Einlehung des vorliegenden Bandes läßt jedenfalls erahnen, was es damk auf sich hat. Der Band selbst aber ist eine prächtige Präsentation eines Tei¬

les dieser Sammlung, nämlich der beschrifteten Siegel des l.Jt. v.Chr. Er will nicht mehr sein, als ein Katalog dieser Objekte und ist deshalb recht knapp gefaßt. Jedes der Siegel - Stempel- sowohl als auch Rollsiegel - wird in Farbaufnahmen und in Nachzeichnung

pubhziert, stets mk sorgfältiger Angabe der Größenverhältnisse. Nach der Umschrift der Inschrift folgt die (vermutliche) regionale Zuordnung, Angaben über Material, Größe,

Ikonographie, Erwerbsort (meist Jerusalem oder London), zeitliche Einordnung und Hin¬

weise auf eventuelle frühere Pubhkationen. Von den 209 Stücken des Katalogs sind 97,

also fast die Hälfte, bisher nicht publiziert.

Die Ordnung ist nicht ganz unproblematisch, da bei den hebräischen Siegeln unter¬

schieden werden „Israelite" von „Israelite or Judean", „Judean" und „Possibly Hebrew Seals". Es folgen phönizische und „possibly Phoenician" Siegel, dann aramäische, am¬

monitische, „possibly Ammonke", moabitische, „possibly Moabite", „possibly Edomite"

und einige zweifelhafte Stücke. Es offenbart sich wieder das alte Dilemma, daß Siegel, die nicht aus Ausgrabungen stammen, aufgrund paläographiseher oder prosopographi¬

scher Kriterien zugeordnet werden müssen, was selten zuverlässig gelingt. So wird man auch hier - vor allem bei den letzten Gruppen - gelegentlich Zweifel an der ethnischen/

sprachlichen Zuordnung haben.

Die hier publizierten Stücke wurden danach ausgewählt, daß sie beschriftet sind, d.h.

das besondere Interesse der Autoren galt den meist sehr kurzen Inschriften; ohne In¬

schrift ist lediglich Nr. 96a, das wegen seiner wahrscheinlich mit Nr. 96 gemeinsamen

Herkunft aufgenommen wurde. Sicherlich wird sich O. Keel mit seinen Schülern der oft

recht originellen Ikonographie der Stempelsiegel annehmen. Auch einige Rollsiegel, alle

mk aramäischen Legenden, sind in dem Buch zu finden (Nr. 106; III; 116; 121; 122; 143

und - zweifelhaft - 206), alle - bis auf Nr. III - bisher unpubliziert. Sehr merkwürdig und

wohl Fälschungs-verdächtig ist das Siegel eines Arsam, ein Chalzedon-Anhänger in fla¬

cher Tropfenform, auf dessen Vorderseite 3 Hirsche und 4 Rehe und auf der Rückseite ein Reiter auf der Löwenjagd zu sehen sind, fast alle in ganz ungewöhnlicher Frontalansicht.

Der Band endet mit „Onomastic Notes", in denen die Eigennamen der Siegel mit kur¬

zen Hinweisen auf Lkeratur bzw. biblische Parallelen gedeutet und übersetzt werden.

Getrennt davon folgt nach der Bibliographie noch ein Verzeichnis der Eigennamen, das

eigentlich hätte in die „Onomastic Notes" integriert werden können, da es die Namen lediglich mit Referenz auf die Siegel wiederholt. Anderersehs hätte man sich noch Kon¬

kordanzen mit Angabe der Vorveröffentlichungen gewünscht, die ich deshalb nach ein