FOREIGN ELEMENTS IN ICONOGRAPHY OF

MAHISHASURAMARDINI -

THE WAR GODDESS OF INDM

By B. N. Mukherjee, Calcutta

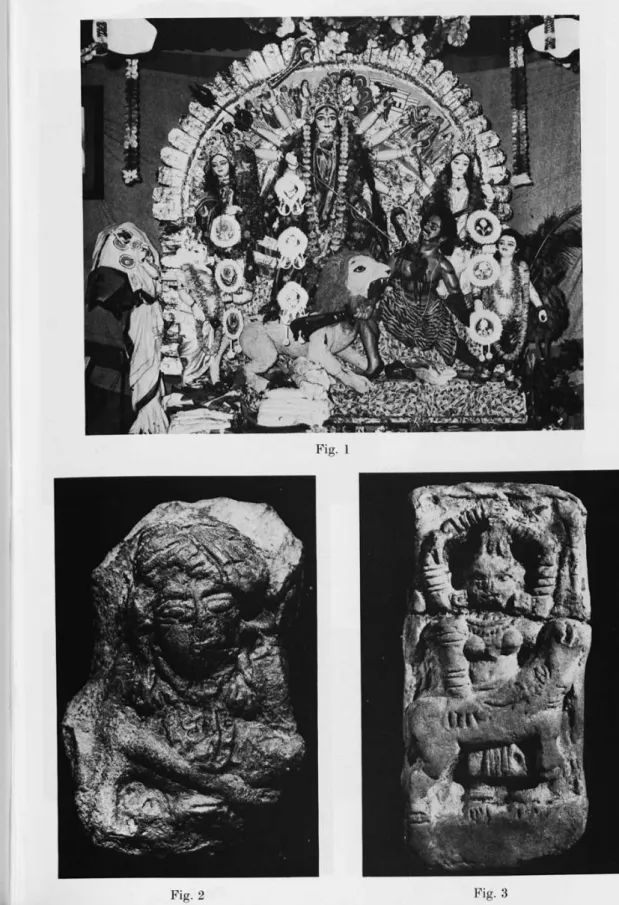

An important feature of the cultural life in India; particularly in its east¬

ern region, is the annual worship ofthe mother goddess Durgä. The mother

is worshipped as riding on a lion and killing a demon (issuing out of a de¬

capitated buffalo). She is shown along with her family members (Sarasvati,

Lakshmi, Ganesa and Kärtikeya and sometimes also Siva) (fig. 1). A por¬

tion of the trunk of a banana tree with leaves is placed by the side of the

group of icons at the time of worship.

The annual festival concerning the goddess (who is shown in the images

concerned as flanked by the deities looked upon as her children) marks in

popular legend, the annual visit to paternal home by Umä (a name of Dur¬

gä). But the real and age old inspiration behind the worship ofthe goddess

riding on lion and destroying a Buffalo demon (i.e. the worship of Durgä in

her MahishäsuramardinI form) seems to be the belief that it symbolises

(and also hastens ?) destruction of evil forces (personified by the Buffalo

demon) by superior good and divine powers (represented by the deity),' and

ensures victory, prosperity^ fertility and rejuvenescense of the earth (as

suggested by inter alia the presence of a part of a fresh green banana tree).^

' Märkav4eya Puräna, Cantos LXXXII f The Devimähätmya section ofthe Mär-

kandeya Puräma refers to Mahisha (i.e. Buffalo demon) as "evil-souled" (LXXXII, 6;

F. E. Pargiter (translator): The Märkandeya Purä-na. Calcutta, 1905, p. 473). It

also states that special energies emanating from different deities combined and

formed the goddess Chandikä ("The Violent Lady", a name of Durgä). They gave her weapons, garments and ornaments, and a lion to ride. Equipped with these weap¬

ons, the goddess fought against the demons {asuras) and killed Mahishäsura (Buf¬

falo demon), who had earlier vanquished the gods in a long drawn war between the

gods {devas) and the demons {asuras). The goddess finally ended that struggle in

favour of the gods {Märkandeya Puräna, LXXXII-LXXXIII).

^ In the Devimähätmya section of the Märkandeya Puräna the goddess is reported to have said that "at the time of annual worship that is performed in autumn time, the man, who listens filled with faith to this (poem of) my majesty, shall assuredly through my favour be delivered from every trouble, (and) be blessed with riches, grain and children. From listening to this (poem of) my majesty moreover (come) splendid issues and prowess in battles (and) a man becomes fearless. When men lis¬

ten to this (poem of) my majesty, enemies pass to destruction, and prosperity accrues and their family rejoices" (XCII, 11-14;F. E. Pargitee: op. cit.,pp. 319- 320). Durgä is noted in the Mahäbhärata to have promised victory to Yudhishthira (IV, 6) and also to Arjuna (VI, 23). In the Larikäkända section of Krittiväsa's Rämä¬

yana Räma is noted to have worshipped the goddess before waging war successfully against the demon king Rävana.

^ The Larikäkända section of Krittiväsa's Rämäyana refers to the tying of "a leaf, the manifestation of a new tree" (or "a new leaf, which is the manifestation of a tree") (to the icon ofthe goddess ?) at the time of worship [D. C. Sen (editor) : Kritti- väsi Rämäyarta. 12th impression, Calcutta, p. 460].

Foreign Elements in Iconography of MahishäsuramardinI 405

The worship of Durgä by people with great pomp and pleasure is an old

custom in eastem India. The Ramacharitam of Sandhyakaranandi (12th

century A.D.) speaks of Varendri as "full of festivities on account ofthe

excellent worship of goddess Umä'"* (Durgä). The annual worship ofthe

deity, which continues for four days, takes place in autumn. Kfittaväsa

(born in c. A.D. 1399 or 1432 ?), however, referred to autumn as "untimely"

{akala) and spring as the "correct" season for the worship.' But the Mar-

karujxya Parana, to be dated much earlier than Krittiväsa, speaks of the

"great annual worship which is performed in autumn time".'

The representation often armed Chandi (i.e. Durgä) as Mahishäsuramar-

dini (destroyer of the Buffalo demon) along with her family members (dei¬

ties) is mentioned inter alia in the Kavikankana-Chamfi of Mukundaräma

Chakravarti' (1 6th century A.D.). But we do not generally get such type of

representation before the late mediaeval age, though the goddess (without

being the demong-slayer) is shown in some early mediaeval sculptures (c.

8th-12th century A.D.) as associated with Kärttikeya and Ganesa or with

Lakshmi and Sarasvati.*

In her Mahishamardini-form the goddess Durgä was generally wor¬

shipped alone in early period. In sculptures of early and early mediaeval

ages Mahishamardini is shown (with a very few early exceptions) as stand¬

ing by the side of or riding on a lion (and sometimes standing wdthout a

lion) and killing a buffalo (representing a Buffalo demon)' or a buffalo head¬

ed male'" or a male issuing out ofa decapitated buffalo." Chronologically

* Ramacharitam, III, 25.

^ Krittiväsa put the relevant statement in the mouth of Räma (Äämäj/ona of Krit¬

tiväsa, LahkäkärujM; D. C. Sen: op. cit., pp. II and 460; see also R. C. Majumdar (editor): The Delhi Sultarmte, Bombay 1960, p. 511).

'' Markandeya Puräna, XCII, 11; F. E. Pargiter: op. cit., p. 519.

' Mukundaräma Chakravarti, Kavikahkana Chandi (edited by A. C. Mukhopäd¬

hyäya), Calcutta, 1344 B.S., p. 86.

* For examples we can refer to the icons found at MandoU (Rajshahi district,

Bangladesh) and Mahesvarapasha (Khulna district, Bangladesh) (R. D. Baner¬

jee: Eastem Indian School of Mediaeval Sculpture. Delhi 1933, pl. LVII, nos, a-c). In a sculpture, now in the Indian Museum (Calcutta), the lion-riding goddess holds a child (Kärttikeya) seated on her lap.

' For examples, we can refer to certain representations of the deity found at

Sonkh, Mathura, Nagar and Udayagiri (H. Härtel: "Some Results of the Excava¬

tions at Sonkh - A Preliminary Report". German Scholars on India, vol. II. Bombay

1976, fig. 36; B. N. Mukherjee: Nana on Lion ~ A Study in Kushäna Numismatic

AH. Calcutta 1969, (cited below as NL) pl. XI, nos. 41-42 and pl. XH; G. von Mit¬

terwallner: " The Kushäna Type of the Goddess MahishäsuramardinI as compared to the Gupta and Mediaeval Types". German Scholars on India, vol. II, figs. 1-6).

For examples, we can refer to a relief on the wall of Mahisha (or Yamapuri) mandapa at Mahäbalipuram, a panel on the wall of a verandah of the Durga temple

at Aihole, a panel in the temple called Baital deul at Bhuvaneswar, etc. {NL,

pl. XIII, nos. 45-46).

'' For an example, we can refer to the icon found at Sakta (N. K. Bhattasali:

Iconography of Buddhist and Brahmanical Sculptures in the Dacca Mitseum, Dacca

1929, pl. facing p. 198).

the first appearances of the different forms of the Buffalo demon can be

placed in the order mentioned here.

The earliest datable images of the goddess standing without a lion

(figs. 2-4) or ofthe goddess standing by the side of or on a lion (fig. 5-7)

and killing the buffalo shaped demon cannot be placed before c. 1st century

B.C. -1st century A.D.'^ In fact, a partly broken terracotta figure, which

may perhaps be provisionally recognized as the earliest known representa¬

tion of Mahishasuramardini (fig. 2). has been unearthed at level 26 (ofthe

excavated strata) at Sonkh (near Mathurä), which is dated to about the

period of Süryamitra'^ and so to about the middle of the 1st century B.C.''* A

number of representations of the deity, including the one from a late

Kushäna level (no. 16) at Sonkh, can be assigned to the Kushäna age"

(lst-3rd century A.D.) (fig. 3).

The number of hands of Mahishäsuramardini, as known from available

icons of different ages and from iconographic texts, varies from two to

twenty or twenty-eight or even thirtytwo. However, the earliest known

forms of the deity have only two or four hands" (figs. 2, 3 and 5).

It is also interesting to note that in the earliest known representations

the goddess is shown as strangling the buffalo, i.e. compressing the throat

ofthe animal or pulling out its tongue by one hand and pressing its back by

the other or another hand'* (figs. 2, 4 and 5). Thus (as it has already been

pointed out by G. Mitterwallner"), she appears to press or crush (as

denoted by the verb mrid) the buffalo, an action which justifies the name

Mahishäsuramardini (literally meaning presser, or crusher, or destroyer,

etc. ofthe buffalo demon). However, her principal weapon, viz. trident (in-

süla), almost invariably appears either by her side or in one (or two) of her

hands.In the terracotta plaque, found at level 16 at Sonkh, the goddess

" Lalit Kala, 1955-56, nos. 1-2, p. 73; NL, p. 30, n. 123; H. Häktel: op. cit.,

p. 92; G. VON Mitterwallner: op. cit., p. 205.

H. Härtel: op. cit., p. 80 and fig. 10.

''' Ibid., pp. 74, 84 and 88. In the Mathurä area rulers with names ending in

-mitra and datta ruled immediately before it was conquered by Räjuvula either

towards the end ofthe 1st century B.C. or in about the first decade ofthe 1st centu¬

ry A.D. (B. N. Mukherjee: Mathurä and Its Society, pp. 3 and 11).

H. Härtel, op. cit., p. 92; NL, pp. 118-119; G. von Mitterwallner:

op. cit., pp. 196f

" AgniPurana, ch. 50; T. Gopinath Rao: Elements of Hindu Iconography , vol. I, pt. II, Madras 1914, pp. 106 f; M. Th. Mallmann: Les Enseignements Iconographi¬

ques des Agni Purana, Paris 1963, p. 143; V. S. Agrawala: Indian Art, Varanasi 1965, p. 260 and fig. 183; Archaeological Survey of India, Annual Report, 1911-12,

p. 86andpl. XXXI, no. 13aand 14; J. N. Bai^brjba: Development of Hindu Icono¬

graphy. 2nd edition, Calcutta 1956, (cited below as DHI), p. 498f An image from

Betna has thirty-two hands.

" NL,p\\. 118-119andpl. XI, no. 41;H. Härtel: op. ci<.,fig. 36;G. von Mit¬

terwallner: op. cit., figs. 1-3.

" See above n. 17.

" G. VON Mitterwallner: op. cit., pp. 199 and 210.

See above n. 17.

Foreign Elements in Iconography of Mahishäsuramardini 407

is shown as holding a trisüla by two half-raised hands in an attitude to

thrust it into the back ofthe buffalo^' (fig. 3). In several sculptures ofthe

Gupta age the trident, with a long shaft, is indicated as plunged into the

body of the animal^^ (fig. 8).

It appears that iconographically the two most important features of the

earliest known representations of Mahishäsuramardini are (i) the appear¬

ance ofa lion, and (ii) the deity's act of killing a buffalo (identifiable with

the Buffalo demon).

These features are noticeable in the texts about the iconography of Mahi¬

shäsuramardini appearing in inter alia the Vishnudharmottara Purana, Mat¬

sya Purana and Agni PuranxiP The story of the battle between the deity

and the Buffalo demon is given in details in the Devimähätmya section of

the Markan4eya Parana}'* But none of these texts can be dated to the period

of the earliest icons of Mahishäsuramardini. In fact, though Diu-gä was

known as a great goddess (and perhaps as a mother goddess) even in the

Vedic period,^' no literary source, defiiutely datable to an age prior to the

Ist century B.C. or A.D., refers to her as a lion riding and demon slajdng

deity.There is, however, no gainsaying the feasibility of Durgä's acquir¬

ing a war-like trait before the stipulated period.^'

^' H. Härtel: op. cit., fig. 36.

G. VON Mitterwallner: op. cit., fig. 5.

Vishnudharmottara Puräna as quoted in T. Gopinath Rao: op. cit., vol. I,

pt. II, p. 112; Agni Puräna, 50, 1-6; Matsya Puräna, 260, 55-70. The goddess is

referred to as Chandi in the first and as Kätyäyani in the last text.

Markandeya Puräna, Cantos LXXXII-LXXXIII.

For examples we can refer to the Rig Veda Khila, X, 127, 12, and Taittiriya Aranyaka, X, 1, 7 (where the goddess is referred to as Durgi) and X, 2, 1. See also

M. Bloomfield: A Vedic Concordance. Reprint, Delhi 1964, p. 486. See also below

n. 26.

" It may be argued that the so-called Devi-sükta ofthe Itig Veda (X, 125, 1 f), in which we may notice an exposition ofthe concept of divine energy (sakti) inherent in

everything, there are references to the divine energy as helping Rudra to fight

against the "enemy of prayer" and as fighting for the people (X, 125, 6). No doubt Rudra was later identified with Siva and Durgä came to be regarded as his consort.

But neither Durgä is specifically mentioned here, nor there is any indication ofthe divine energy's association with lion or other fight against demons. In fact, the hel¬

per or associate of Rudra in the hjmin concerned was Väk (the goddess of speech).

So the evidence concerned can at best indicate an inherent war-like trait in the cha¬

racter of the female associate of Rudra. In the Taittiriya Aranyaka the consort of Rudra was referred to as Ambikä (X, 18), a name meaning literally "mother". In the

Väjasaneyi Samhita Rudra's sister was referred to as Ambikä (III, 5). The latter was alluded to in the Taittiriya Aranyaka as the consort of Pasupati (identifiable as Rudra-Siva) [or of Hiranyabähu (identifiable with Siva)] (X, 18). The Taittiriya Aranyaka also mentioned Durgä (see above n. 25), who was destined to be regarded later as Ambä ("Mother") and also as the wife of Siva. So in the above noted name Ambikä (which literally means "mother") we may discern a veUed allusion to Durgä.

This inference suggests that even in the Vedic period Durgä could have been known as a mother goddess as well as a goddess with some war-like traits in her character.

Thus, in the present state of our knowledge, the cult of Durgä Mahishä¬

suramardini may be considered to have begun, as suggested by the above

noted icons, by about 1st century B.C. - 1st century A.D. The central con¬

cept ofthe demon-slaying aspect ofthe goddess probably consisted of (a)

an idea about lion's association with her (fig. 9), and (b) a legend relating

to her killing a demon, symbolising evil (as indicated by later texts).^

* *

*

The association of lion with different non-Indian goddesses was, howev¬

er, known from different periods much earlier than the 1st century B.C. or

A.D. These deities were Sumerian Ninlil (Ninhursag), Phrygian and Lydian

(and so West Asiatic) Cybele, Assyrian Ishtar, Greek Rhea and Athena,

Babylonian Nanä and Persian Anähita^' (fig. 10). They were considered by

In the Mahäbhärata Durgä is referred to as Mahishäsuranäsini (i.e. destroyer of

Mahisha demon) (Virätaparvan, edited by Raghu Virä. Poona 1936, p. 301, 1. 30)

and as Mahishäsuraghätini in the Harivamsa, (III, 3), an appendix to the Mahäbhä¬

rata. Since the growth of the Mahäbhärata is generally dated to the period from 4th century B.C. to the 4th century A.D. [R. C. Majumdar (editor): The Age of Imperial

Unity. Bombay 1951, p. 251], the relevant sections ofthe Mahäbhärata (IV, 6 and

VI, 23) and the Harivamsa (III, 3) need not be placed before 1st century A.D.

Moreover, the section ofthe Virätaparvan in question is considered to be a very late interpolation (Joumal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Ireland and Great Britain (1906), p. 356; Raghu Vira: op. cit., p. 301).

Thus there is no specific reference in Indian literature of pre-Christian Era to Dur¬

gä as having lion as her mount and as the killer of a Buffalo demon. It has been noted that Skanda has been referred to as Mahishärdana ("tormentor of Mahisha")

in the Mahäbhärata (M. Monier-Williams: A Sanskrit-English Dictionary.

Reprint, Oxford 1951, p. 803). But neither the use of this epithet for Skanda in the epic can be definitely dated to a period before A.D. 1, nor can the source of Durga's

concept as Mahishäsuramardini be found in Skanda's epithet.

These inferences stand even if we admit the probability ofthe attribution of war¬

like activities to Durgä in Indian literature prior to the 1st century B.C. or A.D. We only want to emphasise the facts that neither lion was associated with her nor the credit of killing ofa Buffalo demon was attributed to her in Indian literature of pre- Christian era.

" See above n. 26.

See above n. 1. Märkandeya Puräna, cantos LXXXII-LXXXIII; Devibhägava-

tam, V, Ch. 1-19; etc.

^' For references to original sources of information (and discussions on them) concerning these deities see the different volumes of J. Hastings (editor) : Encyclo¬

paedia of Religicn and Ethics. 3rd impression, Edinburgh and New York 1952-1955 (cited below as ERE). (1) For Cybele, see vol. I, p. 415; vol. IV, pp. 377-378; and vol. VIII, p. 848-849; (2) for Ishtar, see vol. VII, pp. 428-434; (3) for Rhea, see vol. I, p. 147; vol. IV, p. 377; vol. VH, pp. 116; and vol. VHI, pp. 847-848; (4) for Athena, see vol. I, pp. 72 and415;vol. VI, p. 381;andvol. XII, p. 695; (5) for Anä¬

hita, see vol. 1, p. 797; (6) for Ninlil (Ninhursag), see vol. II, p. 296; vol. VII, p. 430; and vol. X, p. 161; and also H. Frankfort: T%e Art and Architecture of the

Ancient Orient. Harmondsworth, etc., 1954, p. 29. For Nanä, see NL, pp. 12-18.

Foreign Elements in Iconography of Mahishäsuramardini 409

their devotees as mother goddesses.^" This common trait and the war-like

attributes of at least the majority of them^' should have facilitated their

gradual association and/or identification with one another, as peoples,

worshipping them as goddesses, became familiar with one another. There

are indeed indications that such associations and/or identifications were

accomplished long before the commencement of the Christian Era.''^

Athena, the Greek war-goddess and protectress ofthe good from the evil,

participated, according to a Hellenic belief, in a war between gods and

giants. The gigantomachy is represented in sculptures on an altar at Per¬

gamon, built by Eumenes II in and about the first quarter ofthe 2nd centu¬

ry B.C. Athena is shown in one ofthe sculptured panels as fighting with a

winged (and so half-human) giant (Alcyoneus)''' (fig. 11). In another panel

(or rather in two other panels) a goddess, identifiable with Athena, appears

standing and attacking a giant with a spear, while the lion is attacking the

same or another giant^' (fig. 12).

Rhea, one of the above noted mother goddesses, is also shown on the

altar at Pergamon as participating in the gigantomachy. She sits on a lion''

(fig. 13).

In coimection with recounting the legend of enmity between gods and

giants or demons, we can also refer to the Avestan belief (probably indicat¬

ing an early tradition) that the mounts of (Ardvi Süra) Anähita crushed the

"hates" ofthe daevas'* (meaning "demons" or "devils" in Iranian context).

To her has been traced a ritual called Taurobolium, or sacrifice ofa bull, the

repository of generative power, the slaying of which would ensure regene-

'° See above n. 29.

" See above n. 29.

See above n. 29.

" ERE, vol. XII, p. 695; J. Johnson: TTie New Century Classical Handbook,

(edited by C. B. Avery). London and New York 1962, pp. 187; K. Schefold:

Myth and Legend in Early Greek Art, New York, p. 64.

J. Charbonneaux, R. Martin, and F. Villard: Hellenistic Art, 350-30

B.C., London 1973 (cited below as HA), p. 266; figs. 286f; W. Müller: Der Perga- mon-Altar, Leipzig 1873, figs. 9f; Lucius Ampelius noted in the 2nd century A.D.

that "at Pergamon is a great marble altar, forty feet in height, with colossal sculp¬

tures; it contains the battle of the giants" (Liber Memorialis, Miracula Mundi, 14;

E. Rohd: The Altar of Pergamon. Berlin (East) 1981, p. 2; figs. 6, 8, etc.). See also HA, pp. 267-268.

HA, fig. 288; W. Müller: op. cit., fig. 14.

" HA, fig. 296; W. Müller: op. cit., fig. 47. The theme is treated in two panels displayed in the room of the Staatliche Museen (of East Berlin), where the friezes of the Pergamon altar are now preserved.

HA, fig. 297. In this connection see also W. Müller: op. cit., 26.

Zend Avesta, Aban Yast,III, 13; J. Darmesteter (translator): TheZendAve- stä, pt. II, - The Sirozähs, Yasts, and Nyäyis, Sacred Book of the East, Vol. XXIII (reprint, New Delhi 1965), p. 3.

ration and fertility. This ritual became connected also with the popular

god Mithra, who had some association with Anähita and Cybele.'"'

Thus by or rather before the 1st century B.C. the concept of Mother god¬

dess in West Asia (including Iran) was associated with (a) lion, (b) the

legend of participation in a gigantomachy and killing of giants and (c) a

ritual of killing bull to ensure regeneration and fertility. These traits and

concepts about the Mother goddess could have been easily communicated

to the inhabitants ofthe Indian subcontinent when during the periods ofthe

Indo-Greeks, Scytho-Parthians and especially Kushänas a part ofthe Iran¬

ian world, famihar with Hellenism and various faiths, became incorporated

in a political unit which also included at least parts ofthe Indian subcontin¬

ent. ' As political barriers between the Indian and Iranian world were

removed, parts of both forming a big pohtical unit, there should have been

an increase in the movement of men, trade and ideas within that Indo-Iran¬

ian domain.

■K *

*

There are indeed various indications of inflow of "western" ideas to India in the 1st century B.C. - A.D."*^ A unique gold medal, coin, or token, datable

palaeographically to the 1st century B.C., displays on the obverse a female

figure holding a lotus in half-raised right hand and a Kharoshthi inscription referring to "Ampa, the deity of Pakhalavadi"."*' The inscription obviously

alludes to the female figure as that "of Ampa or Amba (i.e. Ambä), the

deity of Pushkalävati", the city of ancient Gandhära. The reverse of the

gold piece in question bears a bull and the legends ushahhe and tauros, both

meaning "bull". This animal was considered as the theriomorphic form as

well as the mount of Siva."*' So Ampa or Ambä, the consort of Siva,'" was

known in c. 1st century B.C. as the deity of Pushkalävati ("the city of

lotuses") and was represented with a lotus in hand.

The lady with lotus appears also on one side of a group of coins of the

Scytho-Parthian ruler Azes I (second-third quarter of the 1st century

" ERE, vol. vm, p. 850; vol. X, p. 645.

Ibid., p. 754.

A. K. Narain: TTie Indo-Greeks, Oxford 1957, pp. 12 f; B. N. Mukherjee:

An Agrippan Source - A Study in Indo-Parthian History, Calcutta 1970, pp. 235f;

B. N. Mukherjee: Disintegration of the Kushäna Empire. Varanasi 1976, pp. If.

The periods concerned are among the several phases of proto-historic and historic

times when the subcontinent could have been in cultural contact with West Asia.

B. N. Mukherjee: Mathura and its Society - The Saka-Pahlava Phase, Cal¬

cutta 1981, pp. 196-212.

NL, pp. 72-76; pl. V, no. 17.

" Ibid., p. 73.

Ibid., DHL pp. 112-113.

In the Taittiriya Aranyaka, (X, 18) Pasupati (i.e. Siva) is referred to as the husband of Ambikä (i.e. Ambä, both the terms meaning "mother") as well as of (or also called) Umä.

i

Foreign Elements in Iconography of Mahishasuramardini 411

B.C.), bearing on the other the figure of a bull. Identical devices can be

noticed on several other coins of Azes I, which, however, display the fore¬

part of a lion by the side of the female deity.This evidence surely indi¬

cates association of lion with the deity of Pushkalävati, identifiable as

Ambä, the consort of Siva. Thus in about the 1 st century B.C. the consort of

Siva (also known as Durgä) received her mount lion coming from the

"Western" direction.

In this connection we may mention that a lady holding a lotus (or a cor¬

nucopia?) is delineated by the side of a male figure on a number of coins of

the Kushäna king Huvishka. Accompanying legends refer to the latter as

Oesho (= Vesho < Visha < Vrisha, i.e. Siva) and the latter as Ommo [i.e.

Amma < Amba or C7mö(?), both the names referring to the consort of

Siva].'" The lady holding a lotus (or a cornucopia?) appears by the side of

Oesho (Siva) on another variety of Huvishka's coins, where, however, she

is described in the accompanying legend as Nanä.'" Thus the consort of

Siva was completely identified with Nanä by or before the age of Huvishka

(first half of the 2nd century A.D.). This identification could have been

established, as indicated above, even in ca. 1st century B.C.

This identification is further supported by the various concepts of

mother goddesses current in West Asia and Iran in and before the 1st cen¬

tury B.C. and those ofthe cult of Durgä as revealed by the relevant data of

different ages. The employment of lion as the mount ofthe Mother goddess,

the belief in her participation in a war between gods and demons and the

killing of an animal symbolising evil (demonic) forces for ensuring regener¬

ation and fertility, noticeable in different cults of the above noted non-

Indian female deities, are also known to have been among the main concep¬

tual and iconographic elements in the development of the cult of Durgä

Mahishäsuramardini.

There are also other data supporting this hypothesis. One of the early

icons of eight handed Mahishamarsini, produced by the Mathurä school of

art, shows two of her upper hands holding sun and moon symbols (fig. 7).

These two symbols are held also by the two upper hands of a representation

of the above mentioned Anähita on a silver dish found in the famous Oxus

Treasure" (fig. 14).

In a few of her early representations, Mahishamardini wears a peculiar

head-dress'^ (fig. 4). It can be recognised as a corrupt representation ofthe

polos head-dress worn by several deities of Hellenic or Hellenistic origin."

NL, pl. V, no. 15. For the date of Azes I, see B. N. Mukherjee: Central a-Ad South Asian Documents on the Old Saka Era, Varanasi 1973, p. 31; "An Interesting Kharoshthi Inscription", Joumal of Ancient Indian History 10 (1978/79), pp. 108f.

NL, pl. V, no. 16.

Ibid., pl. V, no. 20. See also above n. 47.

NL, pl. V, no. 18.

^' 0. M. Dalton: The Treasure of the Oxus, 3rd edition, London 1964, p. 57;

pl. XXXII, no. 203; NL, pp. 89-90 and 120; pl. XIV, no. 47.

^•^ G. VON Mitterwallner: op. cit., figs. 1-2.

" NL, pl. V, no. 19; pl. VI, no. 21; pl. VII, no. 23; pl. X, no. 39; pl. XV, no. 51; etc.

Even in one of the different names of Durgä we may discern influences from the "western" direction. We are referring to the name Nana, by which

one ofthe above noted non-Indian mother goddesses was known and which

was also used (later) to refer to the Indian goddess in question in one of her

pithas.''' However, one may still try to deny connection of Durgä with the

name of the Babylonian goddess Nanä, since the term nxin/X (meaning inter

alia "mother") is known to have been used in the Rig Veda itself.

* *

*

No doubt, there are some apparent differences between the Mahishamar¬

dini concept of Durgä, the Indian mother goddess, and the ideas about the

non-Indian mother goddesses noted above. But these are explicable.

The evil demon (sometimes represented with non-human features) and

the demonic animal symbolising the evil were understandably identified

with each other (at least at the initial stage of the development of the

Indian cult). The bull was replaced by a buffalo as the former had already

been considered as the theriomorphic representation as well as mount of

Siva, the consort of Durgä, the great slayer of the demon(s). On the other

hand, one may suggest the possibility of induction of an indigenous (and

non-Brahmanical) buffalo-killing female deity into the process, initiated

mainly under foreign influences, ofthe development ofthe concept and ico¬

nography of the lion-riding-cum-buffalo-demon-slaying goddess.'^ But we

have no definite evidence of the historicity of such an indigenous buffalo-

killing deity before the period of the appearance of regular Mahishäsura¬

mardini icons."

In the early representations of her Mahishamardini form the deity con¬

cerned is shown as pressing and strangling the animal by hands and not

using spear (like Athena). From about the late Kushäna age the sculptors

concerned began, at first sporadically, to show her as using inler alia a trid¬

ent for killing the animal. The reason behind showing the deity as killing

the demonic animal by bare hands was perhaps the willingness on the parts

ofthe sculptors to demonstrate her superhuman strength. AVhen a weapon

for the same purpose was thought of, the one which would have automati-

At the pitha of Hingulä (or Hinguläta) or modern Hinglaj in the Baluchistan area of Pakistan the goddess (identifiable with the consort of Siva) is noted to have been locally known even in the present oentury as Bibi Näni (Joumal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, Letters, 1948, vol. XIV, no. 1, pp. 43 and 85).

" Rig Veda, IX, 112, 3.

This point was raised by Prof. H. von Stietencron when the paper was pre¬

sented at the German Orientalists' Conference at Tübingen in March, 1983.

" We are publishing elsewhere our criticism of the theories of S. B. Dasgupta and P. Sengupta about the origin ofthe cult of Mahishäswiamardini ([published in the Bengali works called Bhäratera &akti Sädhanä 0 ääkta Sähitya &nd Bägh 0 Sahs- kritis (edited by S. Mitra)].

'* H. Härtel: op. cit., p. 92.

Fig. 2 Fig. 3

Fig. 10

Fig. 12

I

Foreign Elements in Iconography of Mahishäsuramardini 413

cally suggested itself was trident, an attribute and even a cognizance ofthe

deity's consort Siva."

So the above noted and similar differences caimot minimise the value of

the hypothesis about the indebtedness of the broad concept and iconic

traits of the Indian cult to the non-Indian mother goddesses noted above.

Different ideas about the latter deities were telescoped, transformed, and

mixed with indigenous ingredients in course of moulding the idea and icon

of Mahishasuramardini.

The cult in question probably came into being in the Scytho-Parthian

and Kushäna age.'" The above noted broken terracotta piece from level 26

at Sonkh, which may be at least doubtfully recognised as displaying the

goddess pressing and strangling a buffalo (= Buffalo demon), may even

belong to the period of Süryamitra' '. By that time the Scytho-Parthian rule

had already been well-established in the north-western section of the

Indian subcontinent and, as suggested by an above noted numismatic evid¬

ence, the consort of Siva had received the lion from the western direction

(especially from one of her immediate western neighbours like Nanä?).

Form that period onwards the cult concerned grew steadily.'^ Ultimately

the annual worship of the Mahishäsuramardini form became transformed

into a national festival.

" DHI, pp. 118 and 469; K. K. Dasgupta: A Tribal History of Ancient India - A

Numismatic Approach. Calcutta 1974, pp. 45-46 and 56-57.

See above n. 55.

^' H. Härtel: op. cit., pp. 74, 80 and 88; see also ibid., fig. 10.

" DHI, pp. 492-93.

Fig. 1

A modern image of Durga Mahishasuramardini (shown with her family members).

Fig. 2

A partly broken terracotta figure of Mahisha8uramardini(?) found at level 26 at Sonkh.

Fig. 3

A terracotta plaque showing Durga Mahishäsuramardini, found at level

16 at Sonkh.

Fig. 4

A stone image of Mahishäsuramardini now in the Staatliche Museum fur Völker¬

kunde, Munich.

Fig. 5

A terracotta plaque, showing Durgä Mahishäsuramardini, found at Nagar and now

in the Archaeological Museum, Amer (near Jaipur in Rajasthan).

Fig. 6

A stone image of Durgä Mahishasuramardini, produced by the Mathura school and

now in the Archaeological Museum at Mathura.

Fig. 7

A stone image of Durgä Mahishäsuramardini, produced by the Mathura school and

now in the Museum für Indische Kunst, Berlin (West).

Fig. 8

Durgä Mahishasuramardini on the wall to the left of the door of cave no. 17 at

Udayagiri (M.P.).

Fig. 9

A stone image of the goddess on lion, produced by the Mathura school and now in

the Museum fiir Indische Kunst, Berlin (West).

Fig. 10

An Assyrian seal displaying Ishtar on a lion.

Fig. 11

Athena fighting with a giant in a sculptured panel at Pergamon, now in the Staat¬

liche Museen, Berlin (East).

Fig. 12

Athena attacking a giant in a sculptured panel at Pergamon, now in the Staatliche Museen, Berhn (East).

Fig. 13

Rhea on lion in a sculptured panel at Pergamon, now in the Staatliche Museen,

Berlin (East).

Fig. 14

Anähita on a shver dish or bowl, included in the Oxus Treasure and now in the

British Museum, London.

415

A CLUE TO THE DECIPHERMENT OF THE SO-CALLED

SHELL SCRIPT

By B. N. Mukherjee, Calcutta

One ofthe undeciphered scripts of ancient India is known to epigraphists

as Shell-script {Sankha-lipi)} The script (lipi) is so called because ofthe

superficial resemblance of some of its characters to a conch-shell (sahkha).

One of the inscriptions in this script is noticeable on the back of a stone

horse which has been dug up about a hundred years ago "near the ancient

fort of Khairigarh in the Kheri district" ofthe then North-Western Province

and Oudh and now of U.P. The stone sculpture was later transferred to the

museum in Lucknow.^ It is at present a part ofthe reserve collection ofthe

State Museum, Lucknow. Its accession no. is H219.

I had a chance of examining the inscription on the back of the stone

horse in March, 1983 when Mr. (now Dr.) R. C. Sharma, the Director ofthe

State Museum in Lucknow, kindly allowed me to handle the sculpture. As I

closely scrutinised the inscription and looked at it from deifferent angles

(by moving around the horse), the following features became clear (figs 1,2

and 3).

(1) The inscription ranges from near the rear end of the back of the

horse to a position near the neck. Its total length is 92 cm and the maxi¬

mum height at one place 33 cm.

(2) The inscription consists most probably of six characters.

(3) The style of writing is ornate and cursive.

(4) There are some signs which are clearly comparable with subscript r

(in cases of the first and the fifth characters) and medial vowel signs (at

least in cases ofthe first and the fomth characters) as used in some forms of

the Brahmi script.

' For detailed discussions on the problems relating to the so-called Shell script

see R. Saloman: Shell Inscriptions, Calcutta 1980, (cited below as SI), pp. If;

" Undeciphered Scripts of South Asia", Aspects of Indian Art and Culture, S.K. Saras¬

wati Commemoration Volume, (edited by D. C. Bhattacharyya and J. Chakra¬

varti), Calcutta 1983, pp. 201 f

Of the few unsuccessful attempts made so far to read inscriptions in the Shell characters the most well-known are those cormected with Ci-Aruton Shell inscrip¬

tion (found in Java). The readings of Brandes, Kern and Pleyte were justifiably

questioned by J. Ph. Vogel. As pointed out by him, Brandes and Kern them¬

selves did not publish their readings. Their suggested readings were quoted by oth¬

ers. Vogel observed that "it is quite possible that the two scholars to whom they are due regarded them as merely provisional, as neither of them published his read¬

ing himseir (J. Ph. Vogel: "Earliest Sanskrit Inscriptions of Java" . Publicaties van den OudAeikundigen Dienst in Nederlandisch-Indel (1925), p. 24). For the defects

in the readings offered by K. P. Jayaswal and H. Sarkar, see SI, pp. 60-61.

^ V. A. Smith: "Observations on the Gupta Coinage". Joumal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Ireland and Great Britain (cited below as JRAS) (1893, p. 98.