SAIVA SIDDHÄNTA WITH REFERENCE TO

SIVÄGRAYOGIN'S COMMENTARIES

ON THE SIVAj5rÄNABODHAM

By Jayandra Soni, Innsbrucic

The Sivajmnabodham (SJB) is a text that has the special status of being a

sruti for the religio-philosophical system of Saiva Siddhänta in the form in

which it still survives today, especially in South India. On the basis of this

text the paper discusses the major concepts of the system — the entire text

and translation of the Sivajmnabodham are given at the end and the survey

is based on Sivägrayogin 's commentaries on it; I pointed out at the meeting

that his brief gloss (laghutiliä) provides an excellent overview of the entire sy¬

stem — for reasons of space, the full text of the gloss together with a trans¬

lation cannot be included here. This paper therefore limits itself to a discuss¬

ion of a few points about the origin of the Sivajhänabodham, about the

commentator Sivägrayogin, and then provides a brief summary of the main

tenets of Saiva Siddhänta thought on the basis of Sivägrayogin's commen¬

taries.

About the Sivajhänabodham (SJB)

It has not yet been conclusively established whether the Sivajmnabodham

is a text that is originally in Sanskrit and part of the Raurava Ägama or whe¬

ther it is an independent work and, possibly, originally in the Tamil lan¬

guage. As regards this problem it is interesting to read what the editor Pandit

N. R. Bhatt says with authority in the Preface (pp. ii — iii) to his two-

volume edition of the Rauravägama:^

"There exists a work of 12 s'lolcas, the Sivajhänabodham. This is the fun¬

damental text which is the most important authority of the Saivite philoso¬

phy which is called Saivasiddhänta. Two commentators of these sülras, Sivä¬

grayogin and Sadäsiva Siväcärya claim that these 12 s'lolcas are taken from

the Rauravägama. Certain Tamil commentators even claim that it belongs to

the 12th adhyäya of the 73rd patala called päsavimocana-patala, of the

Rauravägama ...

Published by the Institute Francais d'Indologie in Pondichery, 1961 —

1972. The English translation of the French given here is taken from the

manuscript of my forthcoming book Philosophical Anthropology in Sai¬

va Siddhänta with Special Reference to Sivägrayogin. Delhi: Motilal Ba¬

narsidass.

These twelve sütras do not appear in the abridged version which we are publishing. There is no indication that they could have belonged to this Äga¬

ma nor have we yet found a patala called päs'avimocanapalala. Further, it is not usual to find a patala divided into adhyäyas. Finally, the last ha.U-s'loka which concludes the Sivajhänabodham declares: "evarri vidyäc chivajhäna- bodhe saivärtha-nirnayam" (thus one should know the decision regarding

Saivism in the Sivajnänabodham). From this it seems that it is an in¬

dependent work. However, it is not possible to have a definite opinion on this point since we do not possess a complete manuscript."

The Tamil tradition considers the original text to be in Tamil and com¬

posed in the thirteenth century by Meykaii^hadeva, who influenced the Saiva

Siddhänta tradition in the form in which we know it today.^ Whatever the

situation may be about the problem concerning the origin of the text, it is

without any doubt one of the basic texts, and perhaps also the most im¬

portant one, of the tradition today. The text is extant in both Tamil and

Sanskrit and has inspired several voluminous commentaries on it. In the Sai¬

va Siddhänta tradition the Sivajhänabodham has the same status accorded to

Bädaräyaria's Brahmasütras by the Vedänta tradition.' Akhough the content

of both the Sanskrit and Tamil versions is regarded as being semantically

identical, textually there are many differences in the expressions used.'* One

2 The Tamil version with the famous commentary on it by Arunanti has

been recently published ir German. H. W. Schomerus: Arunantis

Sivajnänasiddhiyär. Die Erlangung des Wissens um Siva oder um die Er¬

lösung. 2 Vols. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag 1981. If the SJB is origi¬

nally in Tamil then one would have to assume that the Raurava Ägama, to which it is claimed to belong, was also originally in Tamil. This raises serious questions about the original language of the Ägamas in general.

Whatever the case may be, many of the extant ones are originally in

Sanskrit, in the Grantha script (a script invented by the South Indians in which to write Sanskrit; many of the letters bear a close resemblance to the Tamil script). Further, if it is true that the SJB was originally in Ta¬

mil, then Meykantha would have to be regarded as the one who 'recalled' it in the 13th century. See Schomerus' above work p. 21 with regard to

how Meykantha was taught it.

' This point is not only significant for the respect shown to the work but one also sees the influence of the Vedänta tradition in the commentaries on this work. This is in any case clear with Sivägrayogin's commentaries on this work, where the influence of the Advaita Vedänta tradition is ob¬

vious; see below for details about his commentaries. For a comparison of the SJB and the Brahmasütras, see K. Sivaraman: Saivism in Philoso¬

phical Perspective. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass 1973, pp. 35—36.

"» Compare the Sanskrit version translated in this paper with the English translation of the Tamil version comprising the bulk of the book by Gor¬

don Matthews: Siva-häna-Bodham. Oxford: University Press 1948.

The German translation of the Tamil version is in the work by Schome¬

rus cited in the previous note, pp. 21—38.

452 Jayandra Soni

of tfie remarkable features of the Sivajnänabodham is that it contains only

12 verses and the Sanskrit version is set to the commonly used anustub

metre, i. e., consisting of 32 syllables, divided into 8 units (pädas) with each unit consisting of 4 syllables. It is certainly one of the shortest treatises of the world's religio-philosophical literature.

About Sivägrayogin

and his commentaries on the Sivajnänabodham

Biographical details about Sivägrayogin are scanty and there is insufficient

authentic historical evidence on which to rely, in attempting to relate bim to

his predecessors and contemporaries with absolute certainty. What we have

are legendary accounts which are given in introductions to Sanskrit texts,

without any supporting evidence. Even his dates cannot be fixed with pre¬

cision, oscillating within a hundred years. However, it seems quite certain

that he flourished in the 16th century, in all probability in the latter half of it^

and according to tradition belonged to the tradition of teachers called the

Skanda-pararhparä.

He is perhaps the only Saiva Siddhäntin who wrote in both Sanskrit and

Tamil* and there is no doubt that he has his own 'brand' of Saiva Siddhänta

that emerges from his commentaries on the Sivajnänabodham. One case in

point, for example, is his conception of the non-difference of the essential

natures of both Siva and the ätman: being under the influence of Advaita

Vedänta, albeit within the confines of the philosophical assumptions of the

5 See my book Philosophical Anthropology in Saiva Siddhänta with Spe¬

cial Reference to Sivägrayogin. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass 1989, p. 39.

' Although Jiiänaprakäsar, his younger contemporary, also wrote in San¬

skrit, he is regarded as being a Saivasamavädin, and not strictly a Saiva Siddhäntin, because of his view "that souls at release are equal to Siva in every respect, a view which is interesting and ably argued but totally at variance with Siddhänta", V. A. Devasanapatthi: Saiva Siddhänta as

Expounded in the Sivajnänasiddhiyär and ils Six Commentaries. Ma¬

dras: University of Madras 1944, p. 9.

' What distinguishes him from the others, e. g., Umäpati (14th century) and Sivajfiänayogin (18th century) may be reduced to one fundamental difference: whereas for Sivägrayogin Siva is both the material and in¬

strumental cause (upädäna-nimhia-kärana) in his sense of the terms and reflects a position which seems to be a qualified vindication of the Siväd- vaita standpoint of Srikantha (12th century) in his commentary on the Brahmasütras, for Umäpati and Sivajfiänayogin, on the other hand, Siva is only the instrumental cause (kevala-nimhia-kärana).

Saiva Siddliänta tradition, Sivägrayogin conceives of a unity or identity that allows what he calls a "slight difference" (Isad-bheda) between the two.^

Apart from a short gloss, Sivägrayogin wrote two other Sanskrit commen¬

taries to the Sivajmnabodham which are much more detailed and lengthy.

The most elaborate one is called the Sivägrabhäsya'^ and the other work,

Saivaparibhäsä^^ which complements it in several respects resembles its scho¬

lastic and systematic approach. The most concise of all these commentaries

is his Sivjmnabodhalaghutilcä.^^ Unfortunately there is no indication in

which chronological sequence these three works, all of which deal specifical¬

ly with the Sivajiränabodham, were undertaken'^ nor is there any evidence

whether they were composed for any specific reason." The Saiva Siddhänta

system is a complicated one and there is no doubt that the Sivajhänabodham

constitutes an excellent and authoritative compendium of the entire system.

It will therefore be useful now to briefly describe some of the main concepts

of the school in the hope that more may be extracted from this short, preg¬

nant work.

8 For details about Sivägrayogin's concept of non-difference (ananyatva) see my book, op. cit., pp. 179—183.

' This was originally published in the Grantha script by Krishna Sastri

(ed.), Madras: Suryanar Koil Adinam 1920, and has never been trans¬

lated in full. My book, cited above, is based largely on this work with translations of several lenghty sections.

10 First published in the Devanägari script by H. R. Rangaswamy Iyen¬

gar and R. Ramasastri (eds.). Mysore: Government Press 1950 (Orien¬

tal Research Institute Publications, Sanskrit Series no. 90.). Another edition of the text is also available, with an English translation by S. S.

Suryanarayana Sastri in R. Balasubramanian and V. K. S. N.

Raghavan (eds.). Madras: University of Madras 1982 (Madras Univer¬

sity Philosophical Series. 35.).

" The edition I have followed here is a copy kindly provided to me by the Adyar Library in Madras. It is a reprint from the Pandit Series, Vol. 29.

Benares: E. J. Lazarus and Co. Nov. 1907. I am grateful to Prof M. Na- rasimhacary of the Madras University for kindly reading this text with me. The responsibility for the translation, however, is mine.

'2 Although the Saivaparibhäsä does not mention the SJB in its title, nor does it contain the 12 verses of the text, as do the other two works by Sivägrayogin, there is no doubt from internal evidence that it too is in fact a commentary on the SJB.

'3 In the Preface to Madras University edition of the Saivaparibhäsä, op.

cit., p. iii, however, it is said that this work "which is a valuable manual on Saiva Siddhänta is comparable to Dharmaräja's Vedänta-paribhäsä of the Advaita school and Sriniväsa's Yatindramata-dipikä of the Visis- tädvaita school."

454 Jayandra Soni

Some important concepts in Saiva Siddliänta

All concepts and ideas in Saiva Siddhänta are directly concerned with the

conception of the three categories (tattva-traya) sivam, ätman and malam,

together with the system of 36 categories which is derived from the last of

these. These three categories constitute uhimate reality and are, therefore, those to which everything can be ultimately reduced. It is convenient to refer

to these as 'impersonal' categories or as existing at the ontological level to

contrast them from their reference as pati, pasu and päsa, which may be con¬

veniently said to be 'personal' categories that operate at the cosmological

level. In other words, when one talks of the world, the beings in it and of a

creator then it is appropriate to speak of these as päsa, pasu and pati. The

world is päsa means that it is a fetter, it binds the beings which exist in it by

limiting their expression and manifestation. Therefore, the beings in the

world are fettered, bound beings, they are pas'us. Both, the world and the

bound beings owe their existence to the creator pati who is the lord not only

of the world but of the bound beings as well (verse 2 speaks of the creator

making the world for man). The creator is personified as Siva whose imper¬

sonal form is referred to in the neuter as sivam. The bound beings, pas'us are

ontologically denoted by the word ätman. The common feature of sivam or

pati, on the one hand, and ätman or pasu on the other hand, is that of cit;

they have a nature that is essentially one of consciousness, i.e., they are ani¬

mate. Their natures are essentially in direct contrast to malam or päsa which

is essentially unconscious, inanimate matter and which stands for the prin¬

ciple of 'impurity' at the ontological level (verse 7).

One way in which to account for these categories is to begin with the idea

of bound beings, which Saiva Siddhänta applies chiefly to man. In the last

part of verse 4 man, whose essence is of the nature of the ätman, is described

as a limited being whose powers of consciousness are hindered by not being

in a position to fully use the powers of willing (icchä), knowing (jnäna) and

doing (kriyä). The instruments at man's disposal are limiting factors and

make possible only a reduced expression and manifestation of the powers

(sakti) intrinsic to his nature of consciousness (cit). It is in this sense that man is also referred to as ariu (verse 3), which literally means small, atomic. The point imphed here is that the abilities of the ätman are reduced to their mini¬

mum. It is assumed that this limitation has a cause, that there must be a prin¬

ciple which operates as a limiting agent. This factor is malam (verse 4) and

because it is a hindrance it is also called päsa, a fetter. And, for the third cat¬

egory, it is argued that since there must be a cause for the existence of the

world, i. e., since there must be a creator of the world (verse 1) and since

there must be a power through which the ätman itself (being overpowered by

malam) is able to manifest its own powers (verses 5 and 11), the concept of

pati or sivam has to be acknowledged. When the term malam is used by itself

it generally refers to the fetter called änava-malam, i. e., the factor which

makes the ätman into an anu, a being that is reduced or restricted. Atiava-

malam is a limiting factor that is said to be born with (sahaja) the ätman and

exists with it since beginningless time (anädi). This is a euphemistic way of

saying that it is not possible to account for the origin of ätman's and

malam's association, or that since we are limited we are not in a position to

grasp the original cause of this association. The ätman is at first completely overpowered by this original fetter and its state is referred to as a forlorn and

isolated one (/cevala-avasthä). Fortunately, however, sivam comes to the as¬

sistance of the ätman and an opportunity is given for the ätman to manifest

itself, albeit still under the limiting influence of äriava-malam. This state of limited expression is called salcala-avasthä.

The opportunity for the ätman's expression is made possible, ironically,

by the lord (pati) providing two other fetters, karma-malam and mäyä-

malam. These are adventitious (ägantuka) fetters, they are made available as

a result of the ätman's contact with änava-malam and in this sense serve a

beneficient function. They make possible a limited expression of the ätman's

powers of consciousness (cit-saktis) in order, eventually, to be completely rid

of all fetters through the fetters themselves. Thus, these two fetters karman

and mäyä have a soteriological function and finaly it is sivam's power of

grace (anugraha-sakti) which detaches the ätman from the influence of

änava-malam, once karma and mäyä have served their function. Their func¬

tion is to allow the ätman to follow a religious discipline which brings about

hberation (moksa or mukti) through the grace of the lord. This grace, or

"descent of grace" as it is called (sakti-nipäta), is necessary in order to re¬

move the overpowering factor of änava-malam. In the Hght of these differ¬

ences in the states of the ätman Saiva Siddhänta speaks implicitly of a 'jour¬

ney' that the ätman undergoes, viz., from an isolated state (kevala-avastha)

to one of limited expression that makes possible the experiences in the world

(sakala-avasthä) and a 'return' to the socalled essential state of purity

(s'uddha-avasthä).

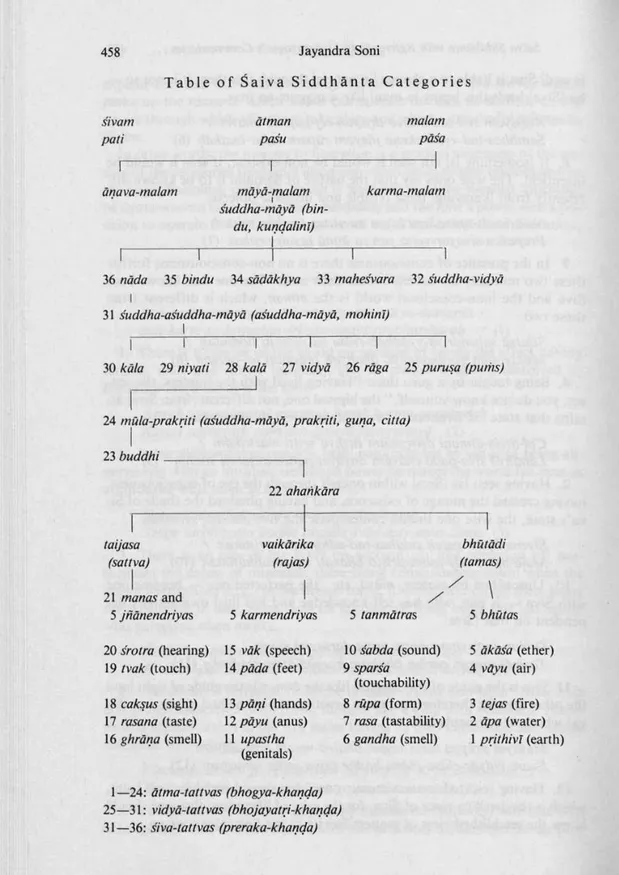

The system of 36 categories is derived from the category of mäyä-malam

(see the tabel of categories for the names of each). Through these categories the ätman is provided with the instruments of experience in the world, instru¬

ments that are able to partially pierce the overwhelming power of äitava-

malam. The limited expression that is in this way provided, is no reflection

on the essential nature of the ätman, i. e., its limitation does not mean that it

cannot become unlimited, free of the limiting agent, malam. The 36 catego¬

ries operate at three different levels depending on when their functions come

into play. The first 24 categories are ätma-tattvas because they provide the

means for the expression of the ätman in the form of experiences in the

world; the next seven categories are called the vidyä-tattvas which make pos¬

sible a knowledge of the experiences, i. e., they are related to the ätman as an

456 Jayandra Soni

experiencer; and the final five categories are called the siva-tattvas which

make up the range in which sivam can operate through its sal<ti, i. e., the

power through which all actions take place and which intrinsically belongs to

sivam.

In other words, the journey to liberation is a gradual awareness of the na¬

ture of the categories through a discipline which bears a close resemblance to

the yogic discipline, until the ätman is 'mature', until the socalled 'ripening'

of änava-malam takes place (mala-paripäka) and the lord's power is in a po¬

sition to operate through the categories of mäyä and bring about liberation.

Sivajnänabodham

Stri-pum-napumsaka-äditväj-jagatah kärya-darsanät /

asti kartä sa hritvaitat-srijaty-asmät-prabhur-harah / (1)

1. There is a creator of the world on account of seeing the effect having

female, male and neuter IgendersI, etc; he creates it having dissolved it;

therefore Hara |Siva| is the lord.

Anyah san vyäptito' ananyah kartä karma-anusäratah /

Karoti sarhsritim pumsäm-äjhayä samavetayä (2)

2. Being different the creator is [stilll non-different by virtue of being all-

pervasive; with an intrinsic, unlimited power he makes the world for man in

accordance with [man's] karman.

Netito mamatodrekäd-aksoparati-bodhatah /

Sväpe nirbhogato bodhe boddhritväd-asty-anus-tanau (3)

3. There is an anu in the body on account of: [the cognition of] not-

thisness; the excess of mineness; there-being consciousness |even| when the

senses have ceased [e. g., in the dream state]; [the recollection of] there being

no experience in deep sleep; and on account of there being one ]an agent |

who perceives when awake.

Atma-antahkaranäd-anyo'py-anvito mantri-bhüpa-vat /

A vasthä-pahcakastho 'to mala-ruddha-sva-drik-kriyah (4)

4. The ätman is different from the internal organs also [apart from citta

and präna\ associated [with them, though [ like a king with ministers. There¬

fore, it \ätman\ exists in the five states having its own knowledge and action restricted by malam.

Vindanty-aksäni pumsä-arthän-na svayam so 'pi s'ambhunä /

Tad-vikäri sivas-cen-na känto'yovat-sa tan-nayet (5)

5. The senses do not know objects by themselves [but only[ with [the help

of] a spirit (puriis) and this [spirit[ with [the help only of [ Sambhu [Siva|. If jit

is saidi Siva is liable to a change jin nature! through this then, it is not so — he ISivaj leads this jspirit in man| like a magnet an iron.

Adrisyam ced-sad-bhävo drisyah-cejfadimä bhavet /

Sainbhosdad-vyatirekena jneyam rüparn vidur-budhäh (6)

6. If Isomething isj not seen it would be non-existent, if seen it would be

insentient. The wise ones say that the nature of Sambhu is to be known dif¬

ferently from IknowingI these [visible and invisible objectsl.

Na-acic-cit-sannidhau kintu na vittas-te ubhe mithah /

Prapahca-sivayor-vettä yah sa ätmä tay oh pri thak (7)

7. In the presence of consciousness there is no non-consciousness; further

these two mutually do not experience each other. The one that knows both

Siva and the |non-conscious| world is the ätman, which is different from

these two.

Sthitvä sahendriya-vyädhais-tväm na vetsi-iti bodhitaft /

Muktvadän gurutiänanyo dhanyah präpnoti tat-padam (8)

8. Being taught by a guru thus: "Having lived with the hunters, the sen¬

ses, you do not know yourself," the blessed one, not different |from Siva| at¬

tains that state |of sivahood], having abandoned these |senses|.

Cid-dris'a-ätmani dristyesam tirthvä vrUti-maricikäm /

Labdhvä siva-pada-chäyäm dhyäyet-pahca-aksarirh sudhi/i (9)

9. Having seen Isa |Siva| within oneself through the eye of consciousness,

having crossed the mirage of existence, and having obtained the shade of Si¬

va's state, the wise one should contemplate the five [sacredI syllables.

Sivenaikyam gatah siddhas-tad-adhina-sva-vnttikah /

Mala-mäyä-ädy-asarhsprisjo bhavati sva-anubhütimän (10)

10. Untouched by malam, mäyä, etc., the perfected one — become one

with Siva — is one, who has self-knowledge and has [hisi own activity de¬

pendent on that [Siva|.

Dris'or-darsayiteva-ätmä tasya darsayitä sivah /

Tasmätdasmin parärn bhaktirh kuryäd-ätmopakärake (11)

11 Siva is the guide of this \ätman\ like the ätman is the guide of sight [and

the other sensesi; therefore, supreme devotion should be had to this one [Si¬

va) who is the ätman's aid.

Muktyai präpya satas-tesäm bhajed-vesarh siva-älayam /

Evarhvidyäc-chivaffiäna-bodhesaiva-artha-nirnayam (12)

12. Having resorted to the virtuous ones, one should worship their habit,

which is the dwelling place of Siva, for the sake of liberation; thus one should know the established view of matters Saivite in the Sivajhänabodham.

458 Jayandra Soni

Table of Saiva Siddhänta Categories

pati

ätman pasu

malam päsa

äriava-malam mäyä-malam karma-malam

suddha-mäyä (bin¬

du, kundalini)

1 \ \ \ 1

36 näda 35 bindu 34 sädäkhya 33 mahesvara 32 suddha-vidyä

I

31 suddha-asuddha-mäyä (asuddha-mäyä, mohini)

i \ \ \ \ I

30 käla 29 niyati 28 kalä 27 vidyä 26 räga 25 purusa (puiris)

24 müla-prakriti (asuddha-mäyä, prakriti, guna, citta)

23 buddhi ,

taijasa (sattva)

22 ahankära

vaikärika (rajas)

bhütädi (tamas)

21 manas and

5 jhänendriyas 5 karmendriyas 5 tanmätras

20 s'rotra (hearing) 15 väk (speech)

19 tvak (touch) 14 päda (feet)

18 caksus (sight) 17 rasana (taste) 16 ghräna (smell)

13 päni (hands) 12 päyu (anus) 11 upastha

(genitals)

10 s'abda (sound) 9 spars'a

(touchability) 8 rüpa (form) 7 rasa (tastability) 6 gandha (smell)

5 bhütas

5 äkäsa (ether) 4 väyu (air)

3 tejas (fire) 2 äpa (water)

1 prUhivi (earth)

1 —24: ätma-tattvas (bhogya-khanda) 25—31: vidyä-tattvas (bhojayatri-khatida) 31 —36: siva-tattvas (preraka-khanda)

Ein wenig bekanntes buddhistisches Mahälcävya

Von Mifhael Hahn, Marburg

1. Wenn man die Gattung des indischen Kunstepos (sargabandha) von

seinen ältesten Anfängen bis ins 12. Jh. betrachtet,' dann fällt auf, daß in

der nachklassischen Periode, die sich von Bhäravi bis Sriharsa erstreckt, ins¬

gesamt nur sieben auf Sanskrit abgefaßte Mahäkävyas bekannt und erhalten

sind: das Kirätärjuniya des Bhäravi (ca. 530—550 n. Chr.), das Jänakiha-

raria des Kumäradäsa (ca. 600 n. Chr.), der Rävariavadiia des Bhatti (vor

650 n. Chr.), der Sis'upälavad/ia des Mägha (ca. 700 n. Chr.), der Haravi¬

jaya des Ratnäkara (zwischen 826 und 838 n. Chr. entstanden), der

Kapphinäbfiyudaya des Sivasvämin (ca. 850 n. Chr.) und das Naisadhacarita

des Sriharsa (ca. 1150 n. Chr.). Textlich und inhaltlich gut erschlossen sind

die Werke von Bhäravi, Bha{ti, Mägha und Sriharsa. Zu diesen vier Werken

gibt es jeweils wenigstens einen einheimischen Kommentar, sie sind alle in

moderne Sprachen übersetzt, und die Zahl der ungelösten TextsteUen ist sehr

gering. Die elementare philologische Arbeit scheint also mehr oder weniger

geleistet zu sein.

2. Von den verbleibenden drei Werken ist offensichtlich nur der Haravi¬

jaya des Ratnäkara von seinem Wortlaut her einigermaßen gesichert.^ Vom

Jänakiharana liegt erst seit 20 Jahren eine vollständige Ausgabe vor,' und

durch die Studie von C. R. SwaminathaN'* wissen wir, daß viele Partien die-

' Sriharsas Naisadhacarita wird allgemein als ein vorläufiger Abschluß die¬

ser Gattung betrachtet, auch wenn Mahäkävyas bis in die Gegenwart ge¬

schrieben werden.

2 Ich beziehe mich auf die folgende Ausgabe: Durgäprasäda and KAslili-

NÄTH PÄND|!|URANG Parab: The Haravijaya of Räjänaka Ratnäkara.

With the commentary of Räjänaka Alaka. Bombay 1890. {Kävyamälä.

22.) Nachgedruckt als Bd. 223 der The Kashi Sanskrit Series durch den Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan, Varanasi 1982. Das Buch Haravijayam

of Ratnäkara. Ed. by Goparaju Rama, das S. P. Bhardwaj im Vish-

veshvarand Indological Journal 21 (1983), S. 306, rezensiert hat, konnte ich bisher nicht einsehen und weiß daher nicht, ob es sich um eine unab¬

hängige Neuausgabe auf der Grundlage von neuem Handschriftenmate¬

rial handeh.

' S. Paranavitana and C. E. Godakumbura: The Jänakiharana of

Kumäradäsa. (Colombo:) Government Press Ceylon 1967.

C. R. Swaminathan: Jänakiharana of Kumäradäsa. A Study, Critieal

Text and English Translation of Cantos XVI—XX. Ed. by V. Ragha¬

van. Delhi 1977. XXI, 163, 96, 95 pp.