Contents lists available atScienceDirect

Zoology

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / z o o l

Biparental immune priming in the pipefish Syngnathus typhle

Anne Beemelmanns, Olivia Roth

∗HelmholtzCentreforOceanResearchKiel(GEOMAR),EvolutionaryEcologyofMarineFishes,DüsternbrookerWeg20,D-24105Kiel,Germany

a r t i c l e i n f o

Articlehistory:

Received30October2015

Receivedinrevisedform8February2016 Accepted6June2016

Availableonlinexxx

Keywords:

Maternaleffects Paternaleffects

Trans-generationalimmunepriming Epigeneticeffects

Host–parasiteinteraction

a b s t r a c t

Thetransferofimmunityfromparentstooffspring(trans-generationalimmunepriming(TGIP))boosts offspringimmunedefenceandparasiteresistance.TGIPisusuallyamaternaltrait.However,iffathers haveaphysicalconnectiontotheiroffspring,andifoffspringareborninthepaternalparasiticenviron- ment,evolutionofpaternalTGIPcanbecomeadaptive.InSyngnathustyphle,asex-rolereversedpipefish withmalepregnancy,bothparentsinvestintooffspringimmunedefence.ToconnectTGIPwithparental investment,weneedtoknowhowparentssharethetaskofTGIP,whetherTGIPisasymmetricallydis- tributedbetweentheparents,andhowthematernalandpaternaleffectsinteractincaseofbiparental TGIP.Weexperimentallyinvestigatedthestrengthanddifferencesbutalsothecostsofmaternaland paternalcontribution,andtheirinteractivebiparentalinfluenceonoffspringimmunedefencethrough- outoffspringmaturation.Todisentanglematernalandpaternalinfluences,twodifferentbacteriawere usedinafullyreciprocaldesignforparentalandoffspringexposure.Inoffspring,wemeasuredgene expressionof29immunegenes,15genesassociatedwithepigeneticregulation,immunecellactivityand life-historytraits.Weidentifiedasymmetricmaternalandpaternalimmuneprimingwithadominating, long-lastingpaternaleffect.WecouldnotdetectanadditiveadaptivebiparentalTGIPimpact.However, biparentalTGIPharboursadditivecostsasshownindelayedsexualmaturity.Epigeneticregulationmay playarolebothinmaternalandpaternalTGIP.

©2016PublishedbyElsevierGmbH.

1. Introduction

Thetransferof non-geneticinformationfromparents tooff- spring is a phenotypic plastic trait that can have fast and long-lastingeffectsindependentofgeneticinheritance(Mousseau and Fox, 1998). Such parental effects are a key source of trans-generationalphenotypicplasticitythatallowforimmediate responsestonovelenvironmentalchallenges(Bondurianskyand Day(2009);BoulinierandStaszewski(2008)).Forinstance,trans- generational immune priming(TGIP), thetransfer of immunity fromparentstoprogeny,enhancesoffspringimmunecompetence andbuffersthemagainstimpactsofpathogensformerlyexperi- encedby theirparents(Grindstaff et al.,2006; Hasselquistand Nilsson,2009;Saddetal.,2005).

Thematernaltransferofimmunologicalactivecomponentslike antibodies viablood, milk,or egg is of major importance dur- ing earlylife stages (Boulinier and Staszewski, 2008; Brambell, 1970a,b;Ehrlich,1892),whentheadaptiveimmunesystemisstill

∗Correspondingauthor.Tel.:+494316004557;fax:+494316004553.

E-mailaddress:oroth@geomar.de(O.Roth).

subjecttomaturation(Lindholmetal.,2006; Rossiter,1996).A mechanismthatenablesparentstopassontheirimmunecompo- nentstotheprogeny,andinthiswayprotecttheiryoungduringthis crucialperiod,shouldthereforebeadaptive(MarshallandUller, 2007).Particularly,iftheprevailingparasiteassemblageissimi- laracrossgenerations,persistentorevenmultigenerationalTGIP might befavoured(Lemkeet al.,1994; Reid et al.,2006).TGIP hasevolvedinvertebrates(Grindstaffetal.,2003;Hasselquistand Nilsson,2009;JiménezdeOyaetal.,2011),butcanalsobefound ininvertebrates,whereitisachievedbyothermechanismsthan antibody-mediatedimmunity(Freitaketal.,2009;Freitaketal., 2014;Littleetal.,2003;Moret,2006;Rothetal.,2010;Saddetal., 2005;Salmelaetal.,2015)

TGIPwasdeterminedasamaternaltrait,becausenon-genetic immunologicalexperiencewassupposedtobeexclusivelypassed onvia the eggor placenta, while sperm cells were considered too small to carry those (Bonduriansky and Day, 2009). How- ever,latelythepotentialofparentaltransferofepigenetictraits influencingtheoffspringphenotypehasbeendiscovered(Jablonka and Lamb, 2014,2015; Jiang et al., 2013).Epigenetics concern stimuli-triggeredchangesingeneexpressionthatdonotinvolve analterationofthenucleotidesequence,butareheritableacross http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.zool.2016.06.002

0944-2006/©2016PublishedbyElsevierGmbH.

generations(Bergeretal.,2009;Gómez-Díazetal.,2012).Subse- quently,factorsthataffectthegeneexpressionbutnottheDNA sequencecanbepassedontothenextgenerationandcontribute tothephenotypicplasticityoftheoffspring(JablonkaandLamb, 2014,2015; Szyf,2015; Youngsonand Whitelaw, 2008). Here, RNAmolecules(RassoulzadeganandCuzin,2015;Rassoulzadegan et al., 2006), DNA-methylation (Ci and Liu, 2015; Jiang et al., 2013) and histonemodifications (Campos et al., 2014; Gaydos et al., 2014; Jones, 2015; Ragunathan et al., 2015; Vilcinskas, 2016,thisissue), factorsassociatedwiththeregulationof gene expression,canbetrans-generationallyinheritedandmanifestas stableepigeneticmarksinthefollowinggeneration(Jablonkaand Lamb,2015;KappelerandMeaney,2010).Environmentalstress- orssuchasparasitesandpathogensmanipulatethehost’simmune systemwhile interfering withhistone acetylation/deacetylation processes (Mukherjee et al., 2012; Mukherjee et al., 2015) or DNA-methylationpatterns(Marretal.,2014).Todate,epigenetic inheritanceofimmuneprimingupon pathogenexposureacross generations based onDNA methylation changes hasonly been demonstratedtooccurinplants(Dorantes-Acostaetal.,2012;Luna etal.,2012),whereashistonemodificationsmightbeassociated withinheritableimmune memoryuponinfectionin eukaryotes (Youngbloodetal.,2010;Ragunathanetal.,2015)andinvertebrates (Vilcinskas,2016,thisissue).However,thequestionwhichmech- anismsareresponsibleformediatingimmuneprimingeffectsthat arebasedonepigeneticchangesinvertebratesisstillunresolved.

Ifepigeneticfactorsareinvolvedorifmalesovercomethemech- anisticbarrieroflimitedspermsize,TGIPmaynotbelimitedto females.Inabeetle,biparentalTGIPwasdiscoveredfirst(Rothetal., 2010;Zanchietal.,2011).Ifbothparentstransfertheirpathogen experiencetotheprogeny,offspringbenefitscouldbemorethan additive(Rothet al., 2010)resulting in an inducedphenotypic plasticity (Jokela, 2010). This could imply an enhanced adap- tivepotentialtohandleparasiticinfections (Marshall andUller, 2007).However,investmentinimmunityiscostlyandtradedoff againstotherlifehistorytraitslikefecundityand/orreproduction (Contreras-Gardu ˜noetal.,2014).Asspecificcostsareassociated withmaternalandpaternalTGIP,anasymmetricinvestmentofthe parentsmayhaveevolved(Zanchietal.,2011).

Biparentalinvestmentinoffspringimmunityalsoexistsinthe sex-rolereversedpipefishSyngnathustyphle(Rothetal.,2012b).

Here, females deposit theireggsinto a protective brood-pouch ofthemales,inwhichtheyarefertilisedandnurseduntilbeing releasedasindependentjuveniles(Berglundetal.,1986;Kvarnemo etal.,2011).Theevolutionofsex-rolereversalcoupledwithan internalbroodingstructuremaymechanisticallyenablea pater- naltransferofnon-geneticfactors.Ourpreviousstudy(Rothetal., 2012b)suggestedthat sex-role reversalmayopenthe doorfor biparentalinfluencesonoffspringimmunity.

Inthepresentstudyweaimedtoinvestigatetheconnection ofTGIPandparentalinvestmentbyunravellingthestrengthand differencesbetweenmaternalandpaternalimpactandtheirinter- activebiparentalinvestmentintooffspringimmuneprotectionin thesex-rolereversedpipefishS.typhle.Wemeasuredtheeffects ofmaternal,paternalandbiparentalTGIPonoffspringimmunity andlifehistorybyutilizinganextendedsetof29immunegenes and15genesrelatedtoepigeneticmodificationprocessesaswell asimmunecellactivityandlifehistorytraits.

Wehypothesisedthat(I)thecombinationofmaternalandpater- nalimmune priming,i.e.biparentalimmunepriming,resultsin a synergisticeffect.By includingtwo differentallopatric bacte- riaspecies for maternaland paternalexposure(Vibrio spp. and Tenacibaculummaritimum)inafullyreciprocaldesign,weexplored whetherbacteria-specificbiparentalimmuneprimingmayharbour additiveimmuneprimingeffects.Wefurtherhypothesisedthat(II) parentalimmunepriminginS.typhleisasymmetricanddirectly

connectedtothereversedmatingsystemwithastronger,long- lastingpaternalimmuneprimingeffect.Toassessthemaintenance ofparentalimmuneprimingwecomparedone-weekoldandfour- month-oldjuveniles.Weexpectedthat(III)theparentalimmune primingeffectwouldceaseuponmaturation,withmaternaleffects ceasingearlierthanpaternaleffects.

Weassessedgenesassociatedwithepigeneticregulationpro- cesseslikeDNA-methylationandhistone-acetylation/methylation toexploretheconnectionbetweenepigenetic modificationand regulationofimmunegeneexpressionanditsnon-genetictrans- ferovergenerations.Wepredictedthat(IV)changesinepigenetic tracesintheoffspringgenerationwouldshowparentalsex-based differences.

Finally, we addressed the costs and benefits of TGIP by monitoringkeylifehistorytraits(size,mass,conditionfactor,hep- atosomaticindex)ofthejuvenilesandevaluatedtheirtimetoreach sexualmaturity.Wehypothesisedthat(V)strengthofmaternal, paternalandbiparentalimmuneprimingpredictstheseverityofa resourceallocationtrade-offandexpectedpaternalandbiparental immuneprimingtobeassociatedwithgreaterenergeticcosts.

2. Materialsandmethods

2.1. Parentalgeneration(P)treatment

Broad-nosedpipefishS.typhlewerecaughtinthesouth-western BalticSea(54◦44N;9◦53E,Germany)inspring2013.Theywere keptunderBalticsummerconditions(salinityof15psu,18◦C,and 14–16hlight)andfedtwiceadaywithmysids.

For theexperimentalsetupmature pipefishwere eitherleft naïve or injected with 50l of 108 cells/ml heat-killed bacte- riasolutionaccordingto(Rothetal.,2012b).Twonovelbacteria species,Vibriospp.(Italianisolate,I2K3)(Rothetal.,2012a)and T.maritimum(DSMNo.17995)(Suzukietal.,2001)wereapplied toexcludeconfoundingeffectswithpreviouspathogenencoun- tersinthewild.Bothbacteriatypesactivatetheimmunesystem offishandcausetwodifferentdiseases:‘vibriosis‘(Alcaideetal., 2001)and‘flexibacteriosis‘(Bernardetetal.,1990;Kolygasetal., 2012),respectively.Thisallowedustoanalysethetransmissionof bacteria-specificimmunememorybymothersandfathers,respec- tively,andpotentialadditiveimmuneprimingeffects.Matingpairs ofimmune-challengedindividualswereformedin36cm×80cm aquariaconnectedtoasemi-flow-throughsystemwithmaternal, paternalorbiparentalimmunechallengeinafullyreciprocalmat- ingdesign:1.(MatV+PatT+),2.(MatT+PatV+),3.(MatNPatT+),4.

(MatNPatV+),5.(MatT+PatN),6.(MatV+PatN),7.(MatNPatN),with (V+) forVibrio, (T+)for Tenacibaculumand (N) fornaïve (seven parentaltreatmentswerereplicated eighttimes,resultingin56 breedingpairs(families)inseparatebreedingtanks)(Fig.S1inthe supplementaryonlineAppendix).AshamexposurewithPBSwas notimplementedasearlierstudieshadsuggestedthatTGIPisnot confoundedbythesterileneedleinjection(Rothetal.,2012b)and shaminjectionwithPBSdoesnotinduceimmunegeneexpression (Birreretal.,2012).

2.2. Filialgeneration1(F1)treatment

All56couplesmatedsuccessfullyaftertheimmunechallenge and aboutfive weeks later (July 2013), one-week-old offspring (8dayspostbirth)wereexposedtohomologousandheterologous heat-killedbacteria(Vibrio(V+)andTenacibaculum(T+)),orstayed naïveascontrols(N).Forthispurpose,aneedlewasdippedintoa solutionof109cells/mlheat-killedbacteriaandusedtoprickthe juvenilesintraperitoneally.Subsequently,thesewerekeptinsep- aratetanksfor20h.Afterthisincubationtime,thejuveniles’body

standardlengthsweremeasured,andwhole-bodysampleswere usedforRNAextraction.Fortheanalysisweselectedonlyfamilies withaminimumclutchsizeof15juveniles,with4replicatesper parentaltreatment(28familiesinall).Fromeachofthe28families, 15offspringwereusedanddistributedoverthethreetreatments, resultingin5specimensperoffspringtreatmentandatotalnumber of420sampledjuveniles.

Remaining F1-offspring (approx. 420 pipefish) were pooled accordingtotheir7parentaltreatmentgroupsandtransferredinto 36cm×80cmaquariaconnectedtoasemi-flow-throughcircula- tionsystemusingthreetankreplicatesperparentaltreatmentanda densityof20pipefishpertank.TocompareTGIPbetweendifferent developmentalstages,four-month-oldjuveniles(notfullysexu- allymature)fromthe7differentparentaltreatmentgroupswere injectedwith20l108cells/mlheat-killedVibrio(V+)orTenacibac- ulum(T+)bacteria(intraperitoneally)orstayed naïve(N),using 3replicatesperoffspringtreatmentpersamplingevent.Intotal, 9individualsofthe7parentaltreatmentgroupswererandomly collectedout of thetanks at two consecutivesampling events, resultinginatotalnumberof126sampledjuveniles.Afterincu- bation(20h),bodystandardlengthandbodymassweremeasured beforethefish weresacrificed. The liverwas weighedand the hepatosomaticindex(HSI=ratiooflivermass[g]relativetobody mass[g])wascalculatedtoevaluatetheenergystatusofthefish (Chellappaetal.,1995).Furthermore,afishbodyconditionfactor (CF)wasdeterminedafterthemethodofFrischknecht(1993).

Forcharacterizingtheimmuneresponse,andtogaininforma- tionabouttheactivityoftheadaptiveandinnateimmunesystem, wemeasuredtheabsolutenumberoflymphocytesandmonocytes intheheadkidneyandbloodaccordingtotheprotocolofRothetal.

(2011).

Remaining F1-offspring (approx. 280 pipefish) were left immunologicallyuntreatedand,tomaintainanequaldensityratio (20pipefishpertank),pooledwithinthematernal,paternaland biparentaltreatmentgroupsandrandomlydistributedintothree tankreplicates.ThetimefortheF1-offspringtoreachsexualmatu- ritywasrecorded.

2.3. Quantificationofgeneexpression

WequantifiedthemRNA-levelof44pre-selectedtargetgenes ofpreviousstudies(Birreretal.,2012;Rothetal.,2012b)using quantitativerealtimepolymerasechainreaction(qPCR).Thegenes wereidentifiedandselectedbasedonanexpressed-sequence-tag (EST)libraryfromS.typhleexposedtonaturalVibrioisolates(Haase etal.,2013).Accordingly,immunegeneswereselectedamongpre- viouslyidentifiedgenesthatweredifferentiallyexpressedinthe pipefishuponinfection(Haaseetal.,2013)andpresumedtobe importanttargetgenesduringourappliedimmunechallenge.The chosengenesweregroupedintofunctionalcategories:(i)innate immune system (immediate and non-specific immune defence upon infection, i.e. phagocytosis), (ii)adaptive immune system (specific antibody-mediated immune defence), (iii) innate and adaptiveimmunegenes(genesconnectedtobothpathways),(iv) complementsystem(complementstheantibodyandphagocytic cell-mediatedimmuneresponse),and(v)epigeneticmodulators (DNAmethylation,histonede/methylation,histonede/acetylation) (TableS6).Primerefficienciesweretested,withallprimerpairs attainingstandardcurveswithslopesoflogquantityvs.threshold cycle(Ct)between−3.6and−3.1andefficienciesof90–100%(Table S7).

TheRNAextractionof420whole-bodysamplesofearly-stage juvenilepipefish(oneweekpostbirth)and126gilltissue sam- plesoflate-stagejuvenilepipefish(fourmonthspostbirth)was performedwithanRNeasy96Universal-TissueKit(Qiagen,Venlo, Netherlands)accordingtothemanufacturer’sprotocol.Extraction

yieldsweremeasuredbymeansofaspectrophotometer(NanoDrop ND-1000;Peqlab,Erlangen,Germany)toallowareversetranscrip- tionintocDNAviaaQuantiTectReverseTranscriptionKit(Qiagen) ofafixedamountof800[ng/l]persample.Thegeneexpression of48geneswasmeasuredusingaBioMarkHDsystem(Fluidigm, SouthSanFrancisco,CA,USA)basedon96.96dynamicarrays(GE chips).Apre-amplificationstepwasperformedbymixinga500 [nM]primerpoolofall48primerswith2.5mlTaqManPreAmp MasterMix(AppliedBiosystems,Waltham,MA,USA)and1.25l cDNApersample.Themixturewaspre-amplified(10minat95◦C;

14cycles:15sat95◦C;4minat60◦C)andtheobtainedPCRprod- uctsdiluted 1:10with low EDTA-TEbuffer. For chiploading,a samplemixwaspreparedbycombining3.5l2xSsofast-EvaGreen SupermixwithLowROX(Bio-RadLaboratories,Hercules,CA,USA) with0.35l20xDNABindingDyeSample&AssayLoadingReagent (Fluidigm)and3.15lpre-amplifiedPCRproducts.Anassaymix waspreparedbycombining 0.7lof 50[M] primerpairmix, 3.5lAssayLoadingReagent(Fluidigm),and3.15llowEDTA-TE buffer.Finally,5lofeachsampleandassaymixwerefilledinto theGEchipsandmeasuredintheBioMarksystem,applyingthe GE-fast96.96PCRprotocolaccordingtothemanufacturer’s(Flu- idigm)instructions.Thesamplesweredistributedrandomlyacross chipsandeachoftheseincludednotemplatecontrols(NTC),con- trolsforgDNAcontamination(-Rt)andstandardsandtwotechnical replicatespersampleandgene.

2.4. Dataanalysisandstatistics

Foreachofthetwotechnicalreplicatespersample,themean cycletime(Ct),thestandarddeviation(SD),andthecoefficientof variation(CV)werecalculated.SampleswithaCVlargerthan4%

wereremoved,duetopotentialmeasurementerrors(Bookoutand Mangelsdorf,2003).Thecombinationofthehousekeepinggenes ubiquitin(Ubi)andribosomeprotein(Ribop)showedthehighest stability(geNormM>0.85)(Hellemansetal.,2007)andtheirgeo- metricmeanwasusedtoquantifyrelativegeneexpressionofeach targetgene bycalculating −Ct-values.Allplots andstatistical testswereperformedinRv3.2.2(RCoreTeam,2015)andPRIMER v6(ClarkeandGorley,2006).Multivariatestatisticswereusedto inferdifferencesin theentireexpressionpattern of29immune genesand15genesassociatedwithepigeneticregulation(Table S6).

Data analysis was conducted on three different levels to address our hypotheses. First, we evaluated maternal, pater- naland biparentalimmuneprimingeffectsincombinationwith thetwo pathogen species(Vibrio andTenacibaculum).Thus, we assessed the effect of seven parental treatment combinations ongene expression(29immunegenes), lifehistory parameters (body size, body mass, CF, and HSI) of one-week-old juveniles and four-month-old juvenilesandimmune cellcountmeasure- ments (lymphocyte/monocyte ratio of blood and head kidney) for the latter. On the second level, we explored the impactof maternaland paternaleffects in thebiparentaltreatmentcom- binationbyexaminingtheF0-parentalxF1-offspringinteraction terms. We elucidatedwhethermaternaland paternaleffects in a biparentalcombination hadadditiveimmune primingeffects.

Onthethirdlevel,weanalyzedmaternal,paternalandbiparental effects on genes associated with epigenetic regulation pro- cesses (DNA-methylation and histone-acetylation/deacetylation andmethylation/demethylation).Parentalbacteria-specificgroups werecombined,merging theparental Vibrioand Tenacibaculum treatmentsintofourparentaltreatments.

ThePERMANOVAmodel(‘vegan’package −‘adonis’function in R) was based on a Bray-Curtis matrix of non-transformed

−Ct-values,applying‘F0-parents’ and‘F1-offspring’ treatment as fixed factors and including ‘family’ as nested factor within

the‘F0-parents’treatmentsand ‘size’ascovariatetocorrect for size-relevantinfluences.Theanalysisofsimilarity(ANOSIM)was performedwiththesoftwarePRIMERv6(Clarke,1993;Clarkeand Gorley,2006)basedonaBray-Curtisdistancematrixand4th-root transformation,whichallowedapairwisecomparisonbetweenthe levelsofparentalandoffspringtreatment.Weappliedaprincipal componentanalysis(PCA)fortheevaluationofdifferentialgene expressionprofilescausedbytheparentaltreatments.Further,we useda between-classanalysis(BCA) toillustratetheinteraction betweenF0-parentaland F1-offspring treatment(Chesselet al., 2004;DolédecandChessel,1987;Thioulouseetal.,1995).Inaddi- tion,a correspondingscatterplotwasaddedtodemonstratethe contributionofeachsinglegene.Here,thedirectionofthearrows determinesthecorrelationbetweenvariables(genes)andprinci- palcomponents.Thelengthofthearrowisdirectlyproportionalto thecontributionofeachgenetothetotalvariability(Oksanenetal., 2007).

Statisticalunivariateapproaches wereappliedforlifehistory parametersandimmunecellcounts.Assumptionsofnormalityfor eachresponsevariableweregraphicallyexaminedandtestedwith theShapiro–WilkandLevinetestsafterBox–Coxtransformation usingJmp9(SASInstituteInc.,Cary,NC,USA).Alinearmodelwas fittedusingthefixedfactors‘F0-parents’and ‘F1-offspring’,the non-independentfactor‘family’or‘samplingday’or‘tank’nested into‘F0-parents’whiletaking‘size’ascovariate.Forthebodysize analysisthesamemodelwithoutcovariatewasused.Allsignificant ANOVASforF0-parentalandF1-offspringeffectswerefollowedby post-hocTukey’sHSDtest.

3. Results

3.1. Maternal,paternalandbiparentalimmuneprimingeffectsin one-week-vs.four-month-oldjuveniles

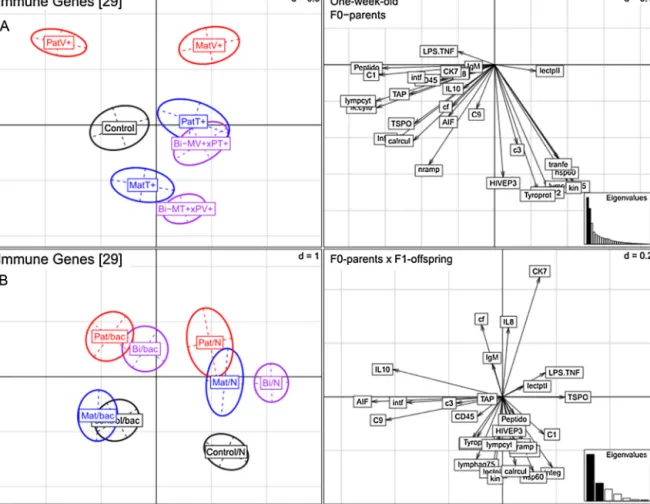

3.1.1. One-week-oldF1-juveniles−immunegeneexpression 29 candidate genes connected to pathways of the innate immune system, the adaptive immune system and the com- plement component system were significantly affected upon the parental bacteria treatments (PERMANOVA-immune:

F6,377=12.44, p<0.001 seeFig. 1A and TableS1 in the supple- mentaryonline Appendix). ThePCA revealed both a difference betweenthetwoappliedparentalbacteriatreatments(Vibrioand Tenacibaculum)andaparentalsex-basedeffect(Fig.1AandTable S2).F1-offspring of mothersand fatherschallenged withVibrio orTenacibaculumdisplayedasignificantlydifferentialexpression profilealongthesecondprincipalcomponent(PC2:18.9%oftotal variation) clustering according to the specific bacteria species (ANOSIM-immune:MatV+vs.MatT+, p=0.001;PatV+ vs.PatT+, p=0.001;Fig.1AandTableS2).However,bothbiparentaltreat- mentgroupsclusteredtogetherwiththematernal-Tenacibaculum aswellasthepaternal-Tenacibaculumtreatments,whichincluded theirrespectivesingleparentalTenacibaculumtreatment(Fig.1A).

Hence,thebiparentaltreatmentsweremoresimilartothemater- nalandpaternalTenacibaculumtreatmentsincomparisontothe parentalVibriotreatment.Particularly,thepaternalTenacibaculum treatmentwasnotsignificantlydifferentfromthebiparentaltreat- mentcomprisingtherespectivepaternalTenacibaculumtreatment (ANOSIM-immune:PatT+vs.Bi-(MatV+PatT+),p>0.05;Fig.1Aand TableS2).

3.1.2. Four-month-oldF1-juveniles–immunegeneexpression In four-month-old juveniles the identical29 immune genes weresignificantlyinfluencedbytheparentalbacteriatreatments (PERMANOVA-immune:F6,98=3.21,p<0.001;Fig.2AandTableS1).

InthemultivariatePCAanalysisweidentifiedadifferencebetween

thetwoparentalbacteriatreatments(VibrioandTenacibaculum) independentoftheparentalsexeffectclusteredinopposeddirec- tionsalongthefirstprincipalcomponent(PC1:27.8%ofthetotal variation)(ANOSIM-immune:MatV+vs.MatT+,p=0.001;PatV+vs.

PatT+,p<0.028;Fig.2AandTableS3).Juvenilesfrombothpater- naltreatmentswerenotsignificantlydifferentfromthoseofthe respectivebiparentaltreatments(ANOSIM-immune:PatT+vs.Bi- (MatV+PatT+),p>0.05;PatV+vs.Bi-(MatT+PatV+),p>0.05;Fig.2A andTableS3)indicatingalong-lastingpaternalimmunepriming effect.

3.1.3. Four-month-oldF1-juveniles–immunecellcounts

Theparentalimmunechallengeoffour-month-oldF1-offspring significantlyaffectedthenumberoflymphocytesandmonocytesin theheadkidney(PERMANOVA-cellshk:F6,97=7.29,p<0.001;Table S1) and blood (PERMANOVA-cells blood: F6,97=4.66, p<0.001;

TableS1).Thelymphocyte/monocyte-ratioofF1-offspringinthe head kidneywas strongly elevatedby the maternal as wellas the paternal Vibrio treatment (ANOVA-LM-ratio hk: F6,73=6.4, p<0.001,TukeyHSD:C<MatV+,C<PatV+;Fig.4AandTableS5).

Incontrast,solelythepaternalTenacibaculumtreatmentelevated the L/M-ratio in F1-offspring (TukeyHSD: C=MatT+, C<PatT+;

Fig. 4A and Table S5). When parents received maternal-Vibrio andpaternal-Tenacibaculum treatmentin a biparentalcombina- tion, the L/M-ratio was significantly raised in contrast to the controlgroup(TukeyHSD: C<Bi-(MatV+PatT+);Fig.4 andTable S5) but showed a similar pattern as the maternal or paternal combinations.In contrasttothat, theL/M-ratioin theblood of F1-offspring waspositivelyinfluenced upon the paternalVibrio treatment only (ANOVA-LM-ratio blood/F0-parents: F6,73=5.15, p<0.001,TukeyHSD:C<PatV+;Fig.4BandTableS5)andfurther revealed a Vibrio-specific offspring treatment effect (ANOVA- LM-ratio blood/F1-offspring: F2,73=7.89, p<0.001, TukeyHSD:

F1-N<F1-V+;TableS5).

3.2. Interactionofmaternal,paternalandbiparentalimmune primingeffectsandbacteriaspecificity

3.2.1. One-week-oldF1-juveniles–immunegeneexpression Basedonthe29immunegenesasignificantinteractionbetween theF0-parentalandtheF1-offspringtreatmentintheone-week- oldjuvenileswasdetected(PERMANOVA-immune:F12,377=1.75, p<0.001;Fig.1BandTableS1).Theappliedpairwisecomparison ofinteractiontermsshowedthatthebiparentalimmunepriming effect was significantly influenced by the paternal Tenacibac- ulum immune challenge. Tenacibaculum-exposed F1-offspring of the biparental treatment Bi-(MatV+PatT+) were not signifi- cantly differentfromTenacibaculum-challenged offspring ofthe singlepaternal Tenacibaculumtreatment (ANOSIM-immune:Bi- (MatV+PatT+)/F1-T+ vs. PatT+/F1-T+, p>0.05; Table S2). With paternalVibriotreatmentthetwogroupsrevealedasignificantly different immune gene expression pattern (ANOSIM-immune:

Bi-(MatT+PatV+)/F1-V+ vs. PatV+/F1-V+, p=0.004; Table S2).

In contrast, both maternal treatment interaction terms were significantly different from both biparental treatment interac- tions(ANOSIM-immune:Bi-(MatV+PatT+)/F1-V+vs.MatV+/F1-V+, p=0023;Bi-(MatT+PatV+)/F1-T+vs.MatT+/F1-T+,p=0.001;Table S2).

Tosimplifythevisualizationofthecomplexinteractionterms, the two respective parental and offspring bacteria treatment groups(VibrioandTenacibaculum)werecombinedintoonesingle bacteriatreatmentgroup(bac)tofocusonparentaleffectsonly.

Asdemonstrated in thebetween-class analysis (BCA), a robust F1-offspring treatmenteffectis explained by thefirst principal component (52.8% of total variation) displaying a clustering of the parental bacteria treatments apart from the parental con-

Fig.1.Immunegeneexpressionofone-week-oldSyngnathustyphleF1-juveniles(N=420).(A)PCAplotbasedon29immunegenesvisualizingtheexpressionprofilesof 7F0-parentaltreatmentgroups(parentalcontrol(Control),paternalVibrio(PatV+)andTenacibaculum(PatT+),maternalVibrio(MatV+)andTenacibaculum(MatT+),and thebiparentaltreatmentgroups(Bi-MV+xPT+andBi-MT+xPV+)).(B)BCAplotbasedon29immunegenesdisplayingtheinteractionoffourF0-parentaltreatmentgroups (parentalcontrol(Control),paternal(Pat),maternal(Mat),andbiparental(Bi))withF1-offspringtreatment(Vibrio,Tenacibaculumcombinedinbacterialchallenge(Bac) versusnochallengeornaïve(N)).Colorsrepresentdifferentparentalbacterialchallenges,withVibrioinred,Tenacibaculuminblueandthejointbiparentalgroupsinpurple.

Thecorrespondingarrow-scatterplotsontherighthandsiderepresentthecontributionofeachvariable(immunegene)tothetotalvariability.Thecontributionofeachgene issymbolisedbythelengthofthearrow,whichisdirectlyproportionaltothecontributionofeachvariable.Thescaleofthegraphsisgivenbygridsizedintheupperright handcornerofeachpanel.TheEigenvaluesarerepresentedbyabarchartinthelowerrighthandcorner,withthetwoblackbarsequivalenttothetwoaxesusedtodraw thePCAorBCAplotandtheircorrespondingscatterplots(A:PC1=24.7%,PC2=18.9%;B:PC1=52.8%,PC2=20.1%).

trol(PERMANOVA-immune: F2,377=18.36,p<0.001;Fig. 1Band TableS1).Moreover,F1-offspringofthebiparentalbacteriatreat- ment,whichwerechallengedwithbacteria(F0-biparental/F1-bac) assembled together with the F1-offspring of the correspond- ing paternal bacteria treatment (F0-paternal/F1-bac), whereas F1-offspringofthematernaltreatmentexposedtobacteria(F0- maternal/F1-bac) were similar to F1-offspring of the control (F0-control/F1-bac)(Fig.1B).

3.2.2. Four-month-oldF1-juveniles–geneexpressionand immunecellcounts

Infour-month-oldoffspringtherewasnointeractionbetween F1-parental treatment and F0-offspring treatment on the 29 immune genes (PERMANOVA-immune: F12,377=0.83, p>0.05;

Fig. 2B and Table S1). The lymphocyte/monocyte ratio in the head kidney of four-month-old juveniles revealed a significant F1-parental treatment and F0-offspring treatment interaction (PERMANOVA-cellshk:F12,97=2.75,p<0.005;TableS1).TheL/M- ratio in the head kidney of F1-offspring with paternal Vibrio challengewasmorepronounceduponhomologousVibrioexposure compared to the heterologous Tenacibaculum treatment, indi- cating a paternal Vibrio specificity effect on the cellular level

(ANOVA-LM-ratiohk:F12,73=2.9,p<0.002,TukeyHSD:F0-PatV+x F1-T+<F0-PatV+xF1-T+;Fig.S2andTableS5).

3.3. Maternal,paternalandbiparentalimmuneprimingeffects connectedtoepigeneticregulationmechanisms

3.3.1. One-week-oldF1-juveniles–geneexpressionofepigenetic regulationgenes

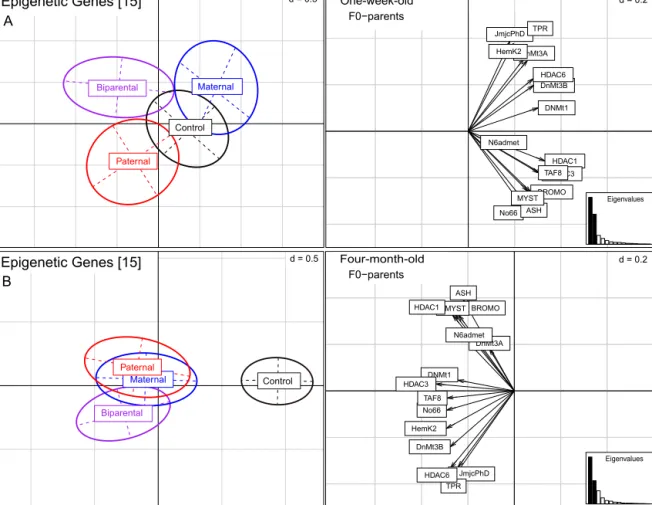

Inone-week-oldF1-offspring15genesresponsibleforepige- neticregulationmechanismslikeDNA-methylationandhistone- modifications displayed a significant parental treatment effect (PERMANOVA-epigen:F6,377=6.6,p=0.001;Fig.3andTableS1).

Toreducecomplexityandfocusonparentaltreatmenteffects,we appliedanANOSIMforpairwisecomparisonsbetweencombined maternal,paternalandbiparentaleffectsindependentofthetwo parentalbacteriatreatments(TableS4).TheANOSIMindicatedthat theeffectwasnotdrivenbytheparentaltreatment,sincetherewas nodifferentialexpressioncomparedtothecontrolgroup(ANOSIM- epigen:Patvs.C,p>0.05;Matvs.C,p>0.05;Bivs.C,p>0.05;Fig.3A andTableS4).Itwasratherduetodifferenceswithinthematernal, paternalandbiparentaltreatments(ANOSIM-epigen:Patvs.Mat, p=0.019;Bivs.Mat,p=0.002,Bivs.Pat,p=0.004;Fig.3AandTable S4).

Fig.2.Immunegeneexpressionoffour-month-oldjuvenilesofS.typhle(N=126).(A)PCAplotbasedon29immunegenesvisualizingtheexpressionprofilesof7F0-parental treatmentgroups(parentalcontrol(Control),paternalVibrio(PatV+)andTenacibaculum(PatT+),maternalVibrio(MatV+)andTenacibaculum(MatT+),andthebiparental treatmentgroups(Bi-MV+xPT+/Bi-MT+xPV+).(B)BCAplotbasedon29immunegenesdisplayingtheinteractionoffourF0-parentaltreatmentgroups(parentalcontrol (Control),paternal(Pat),maternal(Mat),andbiparental(Bi))withF1-offspringtreatment(Vibrio,Tenacibaculumcombinedinbacterialchallenge(Bac)versusnochallenge (N)).ColorsrepresentdifferentparentalbacterialchallengeswithVibrioinred,Tenacibaculuminblueandthejointbiparentalgroupsinpurple.Thecorrespondingarrow- scatterplotsontherighthandsiderepresentthecontributionofeachvariable(immunegene)tothetotalvariability.Thecontributionofeachgeneissymbolisedbythe lengthofthearrow,whichisdirectlyproportionaltothecontributionofeachvariable.Thescaleofthegraphsisgivenbygridsizedintheupperrighthandcornerofeach panel.TheEigenvaluesarerepresentedbyabarchartinthelowerrighthandcorner,withthetwoblackbarsequivalenttothetwoaxesusedtodrawthePCAorBCAplot andtheircorrespondingscatterplots(A:PC1=27.8%,PC2=14.7%;B:PC1=41.6%,PC2=17.3%).

3.3.2. Four-month-oldF1-juveniles–expressionofepigenetic regulationgenes

In contrast to the effects we found for one-week-old juve- niles,epigeneticregulationgenesoffour-month-oldjuvenileswere affected by the parental bacteria challenges in comparison to thecontrolgroup(PERMANOVA-epigen:F6,93=6.6,p=0.001,Table S1; ANOSIM-epigen: Pat vs. Control, p=0.001; Matvs. Control, p=0.006; Bivs.Control, p=0.001;Fig.3BandTableS4). Thisis additionallysupportedinthegraphicalvisualizationofthePCA,in whichparentaltreatmentsarefoundindistinctclustersalongthe firstprincipalcomponent(45.8%oftotalvariation).Nosignificant differencesbetweenmaternal,paternalandbiparentaltreatment couldbeidentified(Fig.3BandTableS4).

3.4. Costsofimmunepriming–lifehistorytraits 3.4.1. One-week-oldF1-juveniles–lifehistory(size)

One-week-oldF1-offspringwithparentalbacteriatreatments hadalargerbodysizethanthecontrolgroup(ANOVA-size.one- week: F2,378=30.04, p<0.001, C<MatV+, C<MatT+, C<PatV+, C<PatT+;Fig.S3AandTableS5).F1-offspringfrommotherschal- lengedwithbacteriaevenrevealedalargerbodysizethanoffspring withpaternaltreatment(TukeyHSD:PatV+<MatV+,PatT+<MatT+;

Fig.S3AandTable7).Inaddition,F1-offspringofmotherswithVib- rioexposurewerebiggerinsizethanoffspringofmotherswith Tenacibaculumtreatment(TukeyHSD:MatT+<MatV+;Fig.S3Aand TableS5).

3.4.2. Four-month-oldF1-juveniles–lifehistory (size/mass/CF/HSI)

Inamultivariateapproach,bodysize,mass,CFandHSIoffour- month-oldjuvenilepipefishweresignificantlyinfluencedbythe parentalimmune challenge(PERMANOVA-life-size/mass/CF/HSI:

F6,98=2.56,p<0.004;TableS1).However,body lengthandmass of four-month-old juvenileswere only increased if exposed to a maternal Vibrio immune challenge. Offspring with maternal Vibrioexposurewere1.35±0.32cmlargerand0.27±0.071gheav- ier than the control group (ANOVA-size: F6,98=2.86, p=0.013, TukeyHSD: C<MatV+; Table S5 and Fig. S3B; ANOVA-mass:

F6,98=4.43,p=0.001,TukeyHSD:C<MatV+,PatT+<MatV+,C<Bi- (MatV+PatT+); Table S5 and Fig. S3C). Further, the paternal Tenacibaculum treatment positively influenced the HSI of F1- offspring,whichhadalargerliver(1.24±0.24mg)thanoffspringof theparentalcontroltreatment(ANOVA-HSI:F6,74=2.39,p=0.034, TukeyHSD:C<T+;TableS1andS5andFig.S3D).

Fig.3. Expressionof15epigeneticgenesfor(A)one-week-oldand(B)four-month-oldjuvenilesofS.typhle.ThePCAplotsarebasedon15genesassociatedwithepigenetic regulationprocesses(DNA-methylationandhistonemodifications)andshowtheexpressionprofilesofcombinedfourF0-parentaltreatmentgroups(parentalcontrol(black), paternal(red),maternal(blue),andbiparental(purple).Thecorrespondingarrow-scatterplotsontherighthandsiderepresentthecontributionofeachvariable(epigenetic gene)tothetotalvariability.Thecontributionofeachgeneissymbolisedbythelengthofthearrow,whichisdirectlyproportionaltothecontributionofeachvariable.The scaleofthegraphsisgivenbygridsizedintheupperrighthandcornerofeachpanel.TheEigenvaluesarerepresentedbyabarchartinthelowerrighthandcorner,with thetwoblackbarsequivalenttothetwoaxesusedtodrawthePCAplotandthecorrespondingscatterplots(A:PC1=44.2%,PC2=28.3%;B:PC1=45.8%,PC2=22.7%).

3.4.3. Six-month-oldF1-offspring–lifehistory(sexualmaturity) Upon a parental immune challenge, juvenile males devel- oped a brood pouch (i.e. sexualmaturity) one month (average 38.6±2days)laterthanoffspringofunexposedparents(ANOVA- maturitymales:F3,168=158.8,p<0.001,TukeyHSD:C<Mat,C<Pat, C<Bi;Fig.S4andTableS5).Ifbothparentsreceivedthebacterial treatment,malesreachedsexualmaturityevenlater(6±1days) (TukeyHSD:Mat<Bi,Pat<Bi;Fig.S4andTableS5).

4. Discussion

4.1. Doescombinedmaternalandpaternalimmunepriming causeamorethanadditiveeffect?

Weexploredthesynergisticeffectsofmaternalandpaternal immuneprimingbyapplyingtwodifferentbacteriaspecies(Vibrio spp.andT.maritimum).Contrarytoourexpectations,thebiparental effectsprettymuchcompensatedeachotheranddidnotpileup to an additiveimpact. In contrast, biparental immune priming withthesamebacteriaphylotypesforbothparentsinducedsyn- ergisticbeneficialeffects(Rothetal.,2012b).Thisdiscrepancymay havearisenduetostrongbacteria-specificimmuneprimingeffects (BeemelmannsandRoth,2016,unpublisheddata).Theimpactof biparental treatment in one-week-old juveniles was driven by Tenacibaculumbacteria,asoffspringreceivingbiparentaltreatment

combinationsrevealedasimilarimmunegeneexpressionprofileas theirsiblingswiththerespectivesinglematernalandsinglepater- nalTenacibaculumtreatments.Incontrast,thefactthattheoffspring treatmentgroupwithsingleparentalVibriotreatmentsclustered farapartfromthecontrolgroupandinanoppositedirectionto theparentalTenacibaculumgroupspointstoanantagonisticVibrio- mediatedparentaleffect.Ourresultsthussuggestthatthebacteria type determinesthestrengthand degreeofbiparentalimmune priming.

Thisbacteria-specificeffectwasalsofoundinfour-month-old juvenilesas indicated bysimilar immunegene expression pro- files.Olderjuvenilesofbiparentaltreatmentgroupsweresolely influenced by the paternal bacteria treatment, independent of theappliedbacteriaspecies.Hence,offspringoffatherswhohad beenchallengedwithVibrioorTenacibaculumbacteriashoweda similarimmunegeneexpressionprofileasoffspringofthecorre- spondingbiparentaltreatmentcombinations,whilethematernal groupsweresignificantlydifferentfromtherespectivebiparental groups. Neither was any synergistic parental immune priming effect detected in four-month-old juveniles, but we did find a dominatingpaternalimmuneprimingeffect.Inlinewiththis,the immunecellactivityintheheadkidneyandbloodoffour-month- old juveniles was upregulated upon the paternal treatmentas comparedtothecontrol.

A

0.0 0.2 0.4

Control MatT+ MatV+ PatT+ PatV+

MatT+PatV+

MatV+PatT+

Lympho cyte/mono cyt e ratio of head kidney (4 −month)

B

0.0 0.4 0.8 1.2

Control MatT+ MatV+ PatT+ PatV+

MatT+PatV+

MatV+PatT+

Lymphocytes:Monocytes[ratio]

Lymphocyte/mono cyt e rati o of bloo d (4 −month)

Lymphocytes:Monocytes[ratio]

Fig.4. Parentaltreatmenteffectsbasedonimmunecellcountmeasurementsof four-month-oldjuvenilesofS.typhle(N=126).(A)Lymphocyte/monocyteratioof headkidney,(B)lymphocyte/monocyteratioofblood.Barplotsaregroupedaccord- ingtoF0-parentaltreatments(parentalcontrol(Control),maternalTenacibaculum (MatT+)andVibrio(MatV+),paternalTenacibaculum(PatT+)andVibrio(PatV+),and biparental(MatT+PatV/MatV+PatT+).Errorbarsrepresentthestandarderrorofthe mean(±sem).

4.2. Dowefindasymmetricparentalimmunepriming?

Consistentwithourhypothesis (II)we identified differences betweenmaternalandpaternalimmunepriming.Ourdataindi- cateasymmetricparentalinvestmentintooffspringimmunitywith astrongerpaternalthanmaternalcontribution.One-week-oldF1- offspringoffathersexposedtoTenacibaculumrevealedanimmune geneexpressionprofilethatcouldnotbedifferentiatedfromthat ofF1-offspringofparents exposedtobiparentaltreatment,also includingthepaternalTenacibaculumchallenge(Bi-(MatV+PatT+) identicaltoPatT+). In thiscombination, we furtheridentified a significantinteractiontermindicating a paternalTenacibaculum specificityeffect.Thissuggeststhatfathersmediatedthebiparental immuneprimingeffect.Four-month-oldjuvenilesevenrevealed stronger paternal immune priming effects independent of the appliedbacteriaspecies. Whenfocussingonlyonthematernal, paternalandbiparentalinteractionterm,wefounda stableand strongerimpactofthepaternaltreatmentonimmunegeneexpres- sionthanthatofthematernaltreatmentforbothone-week-oldand four-month-oldjuveniles.

F1-offspringoffathersexposedtoVibrioorTenacibaculumbac- teriainducedtheirimmunecellproliferationintheheadkidney, themajor immune organ of teleosts, earlier than those of the controlgroup. In addition, a homologous paternalVibrio expo- sure increased the cellular immune defense compared to the heterologouscombination,whichindicatesastrongpaternalVib- riospecificityeffect.Thatthelymphocyte/monocyte-ratiointhe bloodofF1-offspringwasincreasedonlyuponthepaternalVibrio treatmentsuggeststhatthepaternalVibriotreatmentcausedafast

inductionofcellularimmunityinthenextgeneration.Inthecase ofthematernaltreatment,onlytheexposuretoVibrioinducedcell proliferationinthehead-kidneyofF1-offspring,whichhighlights thatmothersonlyprovidedcellularprotectionagainstpotentially familiarVibriobacteria.Theparentalgenerationwaswild-caught intheKielFjordwherepipefishareinconstantcontactwithvari- ousVibriophylotypes(Rothetal.,2012a).Duringthepresentstudy, weusedaVibriophylotypeisolatedfromanItalianpipefish(Roth etal.,2012a),whichwesupposedtobeallopatricandmostlikely noveltotheimmunesystemofBalticpipefish.However,poten- tiallytheepitopestructureofItalianandBalticVibriophylotypesof theirnaturalhabitatwasnotdifferentiableforS.typhleeitherdue tostrongsimilaritiesorduetoimmunologicalcross-reactivity.In contrast,theTenacibaculumbacteriawereisolatesfromadifferent fishspeciesinthePacific(Suzukietal.,2001).Mostlikely,theshort maternalcontacttoTenacibaculumbacteriawasnotsufficientto provideimmunologicallong-termprotectiononthecellularlevel viatheegg.Thecloseconnectiontothefathersduringmalepreg- nancy,however,waslongenoughtoboost thecellularimmune defenseagainstbothexperiencedbacteria.

Theseresultssupportourhypothesis(II)thatinthissex-role reversedmatingsystemchallengedfathershaveastrongerinflu- enceonoffspringimmunity.Sincethefathersarecloselyconnected totheprogenyduringmalepregnancytheyprobablytransferred immunityforalongertimeperiod.In teleosts,femalesproduce costlyeggs,inwhichtheydepositnutritionproteinsandimmune componentsovertheeggyolk(Blyetal.,1986;BobeandLabbé, 2010; Swain et al., 2006). In the sex-role reversed pipefish S.

typhle females oviposit theireggsinto the male’sbrood pouch wheretheyarefertilisedandremainduringpregnancy(4weeks) (Berglund etal.,1986).Freshlyhatchedjuvenilesconsumepro- teinsofthematernalyolksac,butarealsosuppliedwithadditional nutrition and oxygen via the paternal brood pouch (Azzarello, 1991;Carcupinoetal.,1997,2002;Kvarnemoetal.,2011;Ripley and Foran, 2006;Ripley andForan, 2009).Consequently,males and females have different possibilities totransfer non-genetic componentstostimulatetheoffspring’simmunity.Infemales,a depositionintotheeggyolkismostlikely,whilemalesmaytransfer substancesthroughthespermfluidandtheplacenta-likestruc- tureinthebroodpouch.Malesandfemalesseemtohaveevolved differentmechanismstoinvestintotheimmunedefenceoftheir progeny.

4.3. Aretheredifferencesintermsofstabilitybetweenmaternal, paternalandbiparentalimmunepriming?

Parentaleffectsareofshortduration(Lindholmetal.,2006).Yet, inlinewithpreviousfindings(Rothetal.,2012b)ourdataindicate thattheimpactofparentalTGIPpersistedtofour-month-oldoff- spring.TheTGIPeffectsdidnotceaseafterthematurationofthe adaptiveimmunesystem,whichtakesapproximately4–8weeks infish(Magnadóttiretal.,2005).ThecontinuityofTGIPwasinflu- encedbythesexoftheparent.Inaccordancewithourhypothesis (III),paternaleffectswerefoundtobelonger-lastingthanmaternal effects.Infour-month-oldjuveniles,theimpactofpaternalimmune primingonimmunegeneexpressioncouldnotbedifferentiated fromthebiparentaltreatmentcombinations.Thisimpliesthatthe biparentalimpactwasdrivenbythepaternaltreatment.Moreover, immunecellactivityintheheadkidneycamewithspecificityinthe caseofpaternalVibrioexposure,andthepaternalimmunepriming effectwasevenpreservedintheblood.Ourresultsthusindicate thatpaternalimmuneprimingwasdrivingthebiparentaleffectsin four-month-oldjuveniles.

4.4. Canchangesinepigeneticregulationgenesbeattributedto parentalsex-baseddifferences?

In one-week-old F1-juveniles genes involved in epigenetic regulation processes like DNA-methylation and histone acety- lation/methylationrevealednodifferentialexpressionaccording to the parental treatment. Yet, we found paternal effects on histone-acetylation/deacetylationgenes.Throughanalteredtran- scriptional regulation,paternal immune priming mayinfluence offspringimmunegeneexpression,potentiallyfacilitatedviainher- itable immune memorycarried acrossgenerations by histones (Ragunathanetal.,2015).

In four-month-old juveniles, the same genes were affected bymaternal,paternalandbiparentalbacterialchallenge.During developmentandmaturation,DNA-methylationpatternsandepi- geneticmarksareunderconstantchangeandhighlyflexible(Monk etal.,1987;RazinandShemer,1995).Aconsistentpatternofepi- genetictracescanthuslikelyonlybeestablishedaftermaturation whenprogrammingoftheparentalDNAmethylomeiscomplete(Ci andLiu,2015).Recentdataevensuggestthatlong-lastingparental immuneprimingeffectscanbemaintainedviaepigeneticmarks andarepreserveduntilthesecondgeneration(Beemelmannsand Roth, 2016, unpublished data). In contrast to the opinion that TGIPceasesafterthematurationoftheadaptiveimmunesystem, long-lastingTGIPinfour-month-oldjuvenilesandeveninthesec- ondgeneration(BeemelmannsandRoth,2016,unpublisheddata) aremediatedthroughinheritedmaternalandpaternalepigenetic marks.

4.5. Arethereanyallocationtrade-offsandcostsassociatedwith maternal,paternalandbiparentalimmunepriming?

Themaintenance ofinducedimmunityisenergeticallycostly and,therefore,enhancedlevelsofimmunedefenceinprimedoff- springimplytrade-offswithotherfitness-relatedtraits(Lochmiller andDeerenberg,2000;Schmid-Hempel,2011;Zanchietal.,2011).

Inlinewiththis,TGIPexhibitedcostsintermsofprolongedtimeto sexualmaturity.F1-malesofthebiparentaltreatmentneededsig- nificantlylongertoproducebroodpouchtissueand,hence,reach sexualmaturitythanindividualsofuni-maternaloruni-paternal treatments.Thisimplieshighcostsofbiparentalimmuneprim- ing.Aslong-lastingpaternalimmune primingbearsequalcosts asmaternalimmuneprimingin termsofdelayedmaturity,this suggeststhatthepaternalmechanismofimmunetransferismore effectiveand less costly.However, maternally primedoffspring revealedadditionalbenefitsthroughanimprovedbodycondition, asreflectedbylargeroffspringsize,indicatingthatexposedmoth- ersinvestmoreintothecurrentclutchduetothepossibleriskof notsurvivingthenextreproductiveevent(Landisetal.,2015).

5. Conclusion

Our study highlights the difference between maternal and paternalimmunepriminginpipefish.Itsupportsourpredictions ofasymmetricparentalinvestmentintooffspringimmunityand of dominatinglong-lastingpaternal immunepriming. Enhance- mentofimmunityuponpaternalimmunechallengealteredgene expressionandimprovedpathogen-specificimmunecellactivity.

Asoffspringarebornintheirfather’senvironmentandmostlikely experienceasimilarpathogenassembly,transferofasolidlong- termprotection against current pathogens should befavoured.

WhilematernalTGIPhadastrongimpactonyoungjuveniles,it diminishedduringthecourseofoffspringmaturationand came withlowspecificity.Eventhoughmaternaleffectswereweakerand oflowerstability,prolongedreproductiontimewascausedequally

bybothparents.However,thesedetrimentaleffectsmaybecom- pensatedbyapositivematernalimpactonoffspringsizeandbody mass.

Itseemsthatparentalpathogenexperienceinduceddifferen- tialand sometimesevenantagonistic geneexpression patterns.

Hence,ina biparentalcombinationwithtwo differentbacterial species,thespecifictypeofbacteriumdeterminedthestrengthand degreeofbiparentalimmunepriming.Thisledtoacompensated biparentalimpactinsteadofsynergisticadditivebiparentaleffects ashasbeenshowninapreviousstudythatusedidenticalpathogens forbothparents(Rothetal.,2012b).Asthebiparentaltreatment didnotleadtoanadditivelong-termeffectandalsocausedasevere delayinoffspringmaturation,biparentalimmuneprimingseemsa costlystrategy(Contreras-Gardu ˜noetal.,2014).Ourresultsindi- catethat TGIPhasimportant consequencesontheevolution of lifehistory,host–pathogencoevolutionandparentalinvestment strategies.Wefoundthefirstevidencefortheinvolvementofepi- genetic regulationprocesses like DNA-methylation and histone acetylation,whichbothparentsaffectedmorewithincreasingage oftheiroffspring.Wesupposethatmaternalandpaternalepige- neticmarksmightmediatelong-termprotection.Furtherresearch shouldfocusonparentalDNA-methylationandhistoneacetyla- tionpatternsuponpathogenexposuretounravelthemechanisms behindTGIP.TostudywhetheritholdstruethatTGIPcorrelates withparentalinvestment,matingsystemswithvaryingmaternal andpaternalcontributionsshouldbeexamined.

Acknowledgments

WethankMaudePoirier,SophiaWegner,MartinGrimm,Verena Klein,FabianWendt,JoaoGladeck,IsabelKeller,SusanneLandis, JoannaMiest,DianaGill,FranziskaBrunnerandAndreaFrankefor supportduringexperimentalfieldandlabwork.Thisstudywas financedbygrantstoO.R.fromtheGermanResearchFoundation (DFG,project4628/1-1,associatedwiththePriorityProgramme SPP1399,Host–ParasiteCoevolution)andtheVolkswagenstiftung.

A.B.wassupportedbyastipendfromtheInternationalMaxPlanck ResearchSchoolforEvolutionaryBiology(IMPRS).

AppendixA. Supplementarydata

Supplementarydataassociatedwiththisarticlecanbefound,in theonlineversion,athttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.zool.2016.06.002.

References

Alcaide,E.,Gil-Sanz,C.,Sanjuan,E.,Esteve,D.,Amaro,C.,Silveira,L.,2001.Vibrio harveyicausesdiseaseinseahorse,Hippocampussp.J.FishDis.24,311–313.

Azzarello,M.Y.,1991.SomequestionsconcerningtheSyngnathidaebroodpouch.

Bull.Mar.Sci.49,741–747.

Berger,S.L.,Kouzarides,T.,Shiekhattar,R.,Shilatifard,A.,2009.Anoperationaldefi- nitionofepigenetics.GenesDev.23,781–783.

Berglund,A.,Rosenqvist,G.,Svensson,I.,1986.Matechoice:fecundityandsexual dimorphismintwopipefishspecies(Syngnathidae).Behav.Ecol.Sociobiol.19, 301–307.

Bernardet,J.,Campbell,A.,Buswell,J.,1990.Flexibactermaritimusistheagentof

‘blackpatchnecrosis’inDoversoleinScotland.Dis.Aquat.Organ.8,233–237.

Birrer,S.C.,Reusch,T.B.,Roth,O.,2012.Salinitychangeimpairspipefishimmune defence.FishShellfishImmunol.33,1238–1248.

Bly,J.E.,Grimm,A.,Morris,I.,1986.Transferofpassiveimmunityfrommotherto younginateleostfish:haemagglutinatingactivityintheserumandeggsof plaice,PleuronectesplatessaL.Comp.Biochem.Physiol.A84,309–313.

Bobe,J.,Labbé,C.,2010.Eggandspermqualityinfish.Gen.Comp.Endocrinol.165, 535–548.

Bonduriansky,R.,Day,T.,2009.Nongeneticinheritanceanditsevolutionaryimpli- cations.Annu.Rev.Ecol.Evol.Syst.40,103.

Bookout,A.L.,Mangelsdorf,D.J.,2003.Quantitativereal-timePCRprotocolforanal- ysisofnuclearreceptorsignalingpathways.Nucl.Rec.Signaling1,102.

Boulinier,T.,Staszewski,V.,2008.Maternaltransferofantibodies:raisingimmuno- ecologyissues.TrendsEcol.Evol.23,282–288.