a Elite integration

Volltext

Abbildung

ÄHNLICHE DOKUMENTE

key insight in mind and scrutinizing the national academic debate over Chinese elite sport governance, this PhD research moreover makes an original empirical

Therefore, the aim of this study is to summarize the pre- dominant characteristics of the mainstream offensive tactics in German elite youth soccer in the Under-17 age group,

His hair falls deeply onto his forehead in casual, perhaps inten- tional disorder, and if we look into the eyes—which know many things, and not only permitted o n e s — a n d

A sample combination procedure is used to impute missing values of wealth variables to households for which detailed consumption data have been collected.. We make sure to

studying the capitalist spirit in the state of Gujarat with its tradition in business and tentative descriptions in changes might well contribute to studies on the capitalist spirit

The PSP toxin profiles measured in the Disko Bay area very well matched the toxin profiles of several Alexandrium tamarense strains isolated at station 14,

فئاظولا ىلع جيرعتلا نم دبلا ةفرعملا عمتجم رصع يف ةيرئازجلا ةعماجلا هجاوت يتلا تايدحتلا .رئازجلا يف ميلعتلا ةمزأ نع مث ةعماجلل ةيساسلأا ةعماجلل ةيساسلأا

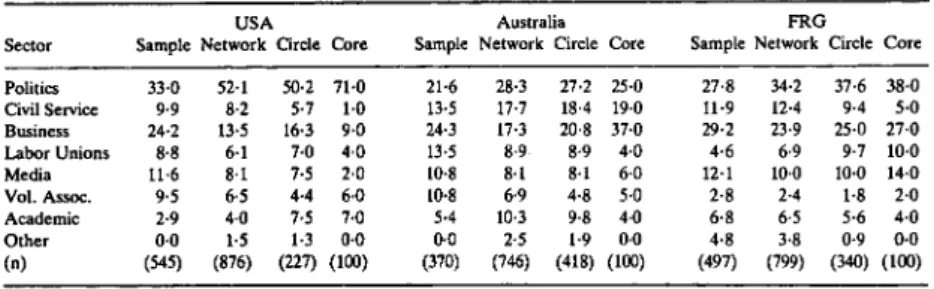

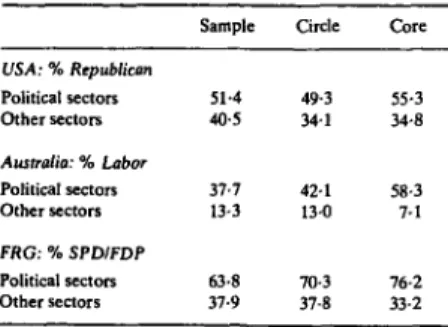

It pays special atten- tion to the social composition of elites and their patterns of interaction between elites (horizontal integration) as well as the relationship between elites