Consumer Behavior

Volltext

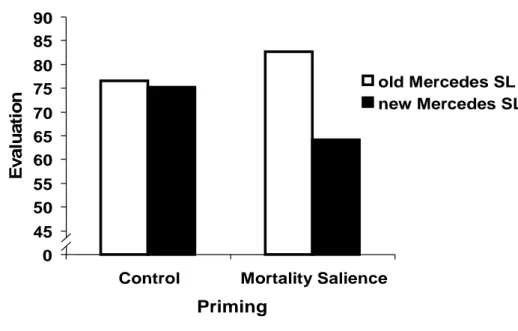

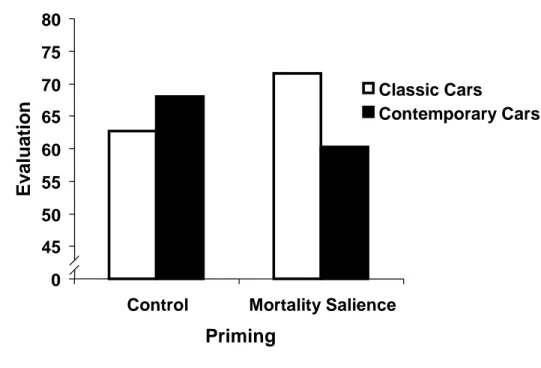

Abbildung

ÄHNLICHE DOKUMENTE

Commercial banks’ housing loans and loans to professional and private individuals, and finance companies’ housing loans and hire purchase loans for cars and consumer durables..

neuroscience, cognitive science, cognitive neuroscience, mathematics, statistics, behavioral finance and decision theory in order to create a model of human behavior that not

Self control refers to resources allocated to prefer- ence transformation technology enabling consumers to moderate desire for ordinary consumption by reducing threshold levels

Although the linkage of sensory and consumer research seems of absolute relevance for product development, the combination of both in the ISAFRUIT HoQ is quite complex due to the

At a given price, they demand more the higher the price recommendation is and this effect is stronger when the price recommendation is informative about the quality of the product

Gollwitzer and Schaal (1998) tested the efficacy oftwo types of implementation intentions in promoting task performance. In the goal intention condition, participants only

Pbtscher (1983) used simultaneous Lagrange multiplier statistics in order to test the parameters of ARMA models; he proved the strong consistency of his procedure

1: Descriptive Shower Data and Analysis of Variance Within and Between Households In a next step, we investigate the correlation of the five shower variables (temperature,