By Willem Floor , Bethesda

Summary: An overview is given of the land and the people of the Qazi-Qomuq as well as of the Qeytaq in the northern Caucasus. An annotated list of their respective rulers, respectively the Shamkhal and the Usmi, provides an history of their interaction with Russia, Iran and the Ottomans and an identification whose these rulers were.

Introduction

Whenever one reads a book about the history of the Caucasus one invariably

finds mention of the Shamkhal and Usmi and other local leaders such as the

Nowsal of the Avars and the Ma'sum and Qadi of Tabarsaran. The identifi¬

cation of these leaders, either in the text or footnotes of the book or article

concerned, always remains rather vague and, therefore, unsatisfactory, and

in vain one searches for an article about these rulers in the Encyclopedia of

Islam or the Encyclopedia Iranica. They are briefly mentioned in the articles

on Dagestan, Qeytaq, and Qumuq, but the fare offered there is rather meag¬

er. 1 Thus, to satisfy my own curiosity I set out to find out more about these

Caucasian leaders. The result is offered herewith.

The whole country of Dagestan is divided into small districts, or lordships, each under the jurisdiction of its proper lord, or myrza, who though heredi¬

tary, is nevertheless not absolute, but his authority is controuled by that of some chief men among them. All these petty lords acknowledge one, who they call shafkal, as supreme head, to whom they pay respect, but not passive obe¬

dience. These people are generally very mischievous, barbarous, and savage, living for the most part by robbery and plunder; a great part of their livelihood is for the men to steal children, not sparing even those of their own nearest re¬

lations, whom they sell to the neighbouring Persians, leaving the care of their cattle to their wives in their absence. 2

Because of this patchwork of peoples, even the Safavid officials, who had di¬

rect and regular contact with the Shamkhal and other Caucasian chiefs, were

1 See also Pursafar 1377/1998; this does not add any information to already pub¬

lished materials.

2 Bruce 1970, pp. 320-321; see also Olearius 1971, p. 729.

confused with whom they were dealing. Generally, they considered anyone

living north of Darband Cherkes or Circassian, and anybody south of it as

Lezgi. But even that simple division was not always helpful. For despite the

honors shown to the Shamkhal's representatives at court and his requests

as well as the subsidies given to him and other chiefs it would seem that the

Safavid political elite had no proper understanding of who the Shamkhal

and his people were. For example, one Safavid historian when writing about

the Shamkhal, called him "the Georgian prince". 3 That this was not an in¬

cidental fluke is shown by the listing of "Gol Mohammad Khan b. Sorkhey

Khan Shamkhal and the other Georgians", some 60 years later. 4 But even

when a Safavid chronicler knew that the Shamkhal was not a Georgian he

still did not have a clear idea who exactly he was and how he differed from

other Lezgis and/or Cherkess. For example, one source mentions that Elqas

Mirza, the rebelling brother of Shah Tahmasp I, was staying "in the neigh¬

borhood of Tarku, the residence of the Shamkhal of the Qeytaq (dar havali-

ye Tarqu dar al- molk- e Shamkhal-e Qeytaq)". 5

I. Shamkhal

The Land and the People

The Shamkhals of the Qazi-Qomuqs (also found as Ghazi-Qomuqs, to¬

day the Lak) extended their domination gradually beyond their mountains

north-east as far as the coast, into Qomuq (or Qomiq, Qomikh) country.

The territory over which the Shamkhals held sway during the hey-day of

their rule stretched from Tarku on the Caspian Sea to Dagestan including

parts of Tawlestan and the mountains towards Shamakhi.

Not much is known about the early history of the Qazi-Qomuqs and the

Shamkhals, who, for the first time unified all the Qomuqs and various peo¬

ples of northern and eastern Dagestan. The Qazi-Qomuqs were Christians

and pagans in the tenth century ce , when already they had a reputation for

violent marauding. At that time, the first efforts to spread Islam among the

Qomuqs were made. 6 Because having been an early target for islamicization,

the Qazi-Qomuqs later were regarded as the champions of Islam against

the pagan peoples around them and hence they boasted that they were the

3 Don Juan 1926, pp. 140, 153; Allen 1972, vol. 2, p. 593 has shown that the Shevkal referred to is

acase of mistaken identity.

4 Valeh Qazvini 1380/2002, pp. 626, 644.

5 Shirazi 1369/1990, p. 96.

6 Minorsky 1958, pp. 51, 65, 72, 96-97,

Qazi-Qomuqs, i.e., warriors of the faith. However, it was only during the

fourteenth century that they were finally islamicized. 7

After the conquest of Iran and neighboring areas by the Mongols (mid-

thirtheenth century), the Caucasus became a battlefield between the Ilkhans

and the Golden Horde. The border between the two empires was formed

by Darband, which consequently was often the scene of battle and pillage

as were its neighboring areas, including Tarku. The same battle was con¬

tinued between Timur and the Golden Horde. When Timur gave its leader,

Toqtamesh Khan, a decisive defeat, the Golden Horde never recovered. Al¬

though the mountain peoples of the Caucasus generally were able to remain

independent this came at a cost, for they had to fight for it with considerable loss of life. 8

The Shamkhals used to spend the winter at Buynaq, a village on the coastal

plain, and the summer at Qomuq (Qomukh) in the mountains, where the

tombs of the early Shamkhals are. In 1578, when Shamkhal Chubin died,

his lands were divided among his sons. This division led to the break-up of

the Shamkhal's realm, first with the loss of control over the area between

the Terek and Sulaq rivers. This was followed by the loss of the Darghin and

Qazi-Qomuq regions. The Qazi-Qomuqs gradually weakened the Sham¬

khal's hold over them and finally, in 1640, they declared themselves entirely

independent of their ruling house. After the death of the Shamkhal Sorkhey

Mirza, in 1639-1640, the Shamkhals only ruled the coastal region from Buy¬

naq to Tarku (Tarki). None of the later Shamkhals ever returned to Qomuq

(see below) and Tarku became the Shamkhal's official capital.

Enderey or Andreeva was part of the Shamkhal's territory as were Buynak,

Aq Su, Kostak and Bammutalah, each of which were under a member of the

Shamkhals' family. Thus, it consisted of lowland, foothills and mountainous

areas. Usually, foreigners only saw the lowlands, which were situated

between the right bank of the Terek, the left of the Sulak, and the west of the Caspian, ... It is a low-lying strip of level land bordering the Caspian, where rivers stop their courses before reaching the sea, and forms numerous lakes and marshy tracts, breeding fevers, for which this region is notorious. 9

7 Barthold/Kermani 1986.

8 Spuler 1965, p. 276; Forbes Manz 1989, pp. 71-72.

9 Morgan/Coote 1971, vol. l,p. 128. The Shamkhal did not control the area between Darband and Astrakhan as submitted by Bournoutian 2001, p. 412. "At first the Rus¬

sians only used the name of 'Lezgians' for the tribes of southern Daghistan, as opposed to the 'highlanders' of the northern territories or 'Tawli', from the Turkish taw-mountain."

(Barthold 1965).

The main seat of the Shamkhal was at

The town of Tarku is called also Tirck or Tarki, and by the Persians Targhoe.

It is open and stands against a mountain upon the Caspian sea, to the east of Georgia, under the dominion of his Czarian majesty, and about three days from Nisawaey. 10

The palace of the Shamkhal was situated in the highest part of Tarku. 11

So much was the land identified with its ruler that in 1558, M organ

when sailing past its coastline mentioned that it "was called Skafcayll or

Connnyke." 12 The situation had not changed some 140 years later when L e

B

ruyn wrote:

This coast is very dangerous, because of the Samgaels who inhabit these moun¬

tains, and who plunder on all sides, so that there is no landing among them.

They are Mohammadans, and lay hands on all the goods of such ships as have the misfortune to strike upon their coast, and think themselves under no obli¬

gation to account for them, but to their natural Prince. 13

The Persians used the term in a similar manner, i.e., as a generic label for the

Cherkes or Lezgis. For example, a son of Chuban I Shamkhal, who served at

the Safavid court, was called Shamkhal Soltan Cherkes to denote the general

area where he was from. The same intention is clear from the use of the term

Usmi Shamkhal, where it is clear that the author used the qualifier Shamkhal

as a geographical term to better contextualize the Usmi.

A Russian report, dated 1675, describes the travel duration of the land

route from Astrakhan to Shamakhi as follows:

From Astrakhan to Terek by land-route 7 days, to the village of Ondrew [En- derey] one day, to Torkov [Tarku] 2 days, to Buinakov [Buynaq] 2 days, to Usmei [i.e. the land of the Usmi] one day, to Derben [Derbend] one day, to Shemakha 5 days. 14

The description of this route makes it clear that the Shamkhal and Usmi

were controlling this trade route between Russia and Shirvan and although

they sold their protection to travelers (commercial or otherwise) they did

not eschew high-way robbery. For the land of the Shamkhal and Usmi had

10 Le Bruyn 1737, vol.

1,p. 143. Ironically after the Shamkhals' realm had been incor¬

porated into the Russian empire it became known as "the district of Shamkhaul"

(Keppel 1827, vol. 2, p. 245).

11 Gärber 1732, pp. 32-33. For a plan of the Shamkhal's Tarku see Olearius 1971, p. 728 and Lerch 1791, p. 30.

12 Morgan/Coote 1971, vol.

1,p. 128; see also vol. 2, p. 466; Kakasch de Zalonke- meny 1877, p. 66.

13 Le Bruyn 1737, vol.

1,p. 142.

14 Gopal 1988, p. 86.

a very bad reputation, because its inhabitants not only were occupied with

cultivation and herding, but also were engaged in highway robbery, cattle

rustling and slave raiding. Even ambassadors and those employed by them

were not safe from being plundered by the Shamkhal's subjects and other

Caucasian peoples. Olearius devotes some space in his travelogue to his

embassy's concern on this account, although it finally remained scot-free. 15

In 1718, one of the members of the Volinsky embassy was sent with an el¬

ephant, horses and 30 Russian soldiers to Astrakan. Between Darband and

Tarki "he was attacked by some hundreds of the mountaineers, called Shaff-

kalls, who killed one man and two horses, and wounded several men and the

elephant." 16 A similar event happened in 1712, when the Shevkal only took

one horse from a present sent to Peter I. 17 It is, therefore, no surprise that in

1722, when the Russian army defeated several Dagestani chiefs and occupied

their lands that at the same time it was able to liberate thousands of Russian

slaves, who had been held there. 18

The Title and Function

Shevkal, Shefkal, Shelkal, Shafkal, or Shamkhal was the title given to the

chief of the Qomuqs, which was a name that was common to all "Lezgis,

some Daghestanis and Tawlintzis". 19 Although the Qomuqs had dealings

with the neighboring states, "They are neither subject to the Turk nor the

Persian, but are in general governed by the shafkal, who is their supreme

head." 20 Although most seventeenth century and later sources use the term

Shamkhal, in Russian sources the ruler of the Qomuqs almost invariably

is referred to as Shevkal or Shelkal. 21 While for a long time the Russians

continued to refer to the lord of Tarku as Shevkal gradually his title was

changed into that of Shamkhal in Russian sources as well. This name itself

was the result of local propaganda aimed to shore up the Shevkal's position.

A history of Dagestan written by Molla Mohammad Rafi', known in excerpt

and appended by Kazem-bek to his translation of the Darband-nameh, pur-

15 Olearius 1971, pp. 726-728, 735. In 1687, due to the friendly relation between Iran and the Shamkhal caravans regularly traveled this road, but a few years earlier when the subsidies to the Shamkhal were not paid he allowed his warriors to attacks caravans, of which he received a share (N.N. 1780a, pp. 35, 40).

16 Bell of Antermony 1788, vol. 1, p. 165.

17 Bournoutian 2001, p. 75.

18 Bruce 1970, pp. 312, 350-351.

19 Gärber 1732, p. 75; Morgan/Coote 1971, vol. 1, p. 128.

20 Bruce 1970, pp. 320-321.

21 Lavrov 1966, pp. 212-214 (shevkal; shelkal); Lavrov 1980, pp. 102-105 (shevkal, shelkal); Gärber 1732, p. 13 (Scheftal); Morgan/Coote 1971, vol. 1, p. 128, (Shalkanles).

ports to relate local legends to uncles of the prophets who migrated from

Sham (Syria) to Dagestan. Hence the etymology of Shamkhal is suggested

to be derived from khal, meaning 'maternal uncle' in Arabic and Sham, de¬

noting Syria or Damascus. From the undated text it is clear that the history

was written to bolster the Shamkhal's claim of overlordship over Dagestan

as it, e.g., was denounced by the Nowsals of Avaria, who were decried as

being descended from pagans and supported by the Rus. 22 According to

Olearius , the word Shevkal or Shamkhal meant 'light' in the local lan¬

guage and he did not report the above propaganda etymology.

As Barthold has rightly argued,

It is not impossible that such etymologies also had some influence on the pro¬

nunciation of the titles in question. It is obviously not by chance that the title of the prince of the Qazi-Qumuq appeared in the oldest Russian documents in the same form (Shewkal or Shawkal) as in Sharaf al-Din Yazdi. Clearly the Persians and the Russians could not have corrupted Shamkhal into Shawkal independently of each other; it is more likely if we assume that the present form of the title only took shape under the influence of the etymology de¬

scribed above. 23

The office of Shamkhal was "not hereditary but elective", 24 although it was

hereditary within the same family. 25 According to Olearius,

the Shamkhal, or rather called shevkal by us, was chosen from among all mir- zas or princes. They all had to stand in a circle and a priest then would throw a golden apple into the circle. The one who got hold of the apple first would become Shamkhal. However, the priest knew very well whom to throw the apple to. The shevkal, meaning Lumen [light], was owed respect by the other princes, but these did not always obey him. 26

22 Minorsky 1958, pp. 8-9. The same story was related to Gärber in 1722 (Gärber 1732, pp. 33-34, "he was descended from Arabs in Damascus, which is called Sham, and chai , which is an Arab title"). Another related derivation of the title, according to the Shamkhal family tradition, is from Shahba'l b. Abdollah b. Abbas, the first Moslem gov¬

ernor of Dagestan in the ninth century. See Bérézine 1852, p. 77, the first part of which has been translated into French by Jacqueline Calmard-Compas 2006, pp. 64, 294;

Rota 1994, pp. 438-439; Fockhart 1958, p. 9, n. 1.

23 Barthold 1965.

24 Bruce 1970, pp. 320-321.

25 See the list of Shamkhals, which makes this clear. Also, Kaempfer 1712, p. 139 (sibi olim haereditariae). I think that Kaempfer is wrong when he states that "quibus honoris gratia adnumeratur Waali Dagestaan", because other governors and chiefs, including in the Caucasus, were called vali, which just means 'governor' in this case (see e.g. below, the vali of Tabarsaran), unless he meant that he was the governor of Dagestan.

26 Olearius 1971, p. 726.

Gärber considered this report about the golden apple to be a fable, without

any basis in fact. 27 According to Bakikhanuf , it was desirable that in case

of the appointment of a new Shamkhal, the elders of the Aqusheh districts

were present, as they were supporting and helping the Shamkhal in most

important activities. 28 This shows that there was some kind of consultation

of notables before the selection was finalized to make sure that there was no

major opposition against his person. Although in the seventeenth century

the Shamkhal's election was formalized by the shah's appointment, he had

the right, when alive, to appoint his successor, who then received the title

Qrim Shamkhal (Crim Schamkhal). 29 The successor, always a family mem¬

ber, was usually based at Enderey. This may explain why Le Bruyn , when

discussing the Shamkhal's realm writes:

It is but seldom taken notice of in our maps. Tho' it be well known there are three or four Princes, the chief of which is him of Samgael, the (2d,) the Crim Samgael ; the (3r,) him of Beki ; the

(4 th,) Caraboedagh Bek, or the Prince of Caraboedagh. The town of Tarku is called also Tirck or Tarki, and by the Per¬

sians Targhoe. It is open and stands against

amountain upon the Caspian sea, to the east of Georgia, under the dominion of his Czarian majesty, and about three days from Nisawaey. 30

Although the Shamkhal had much power, authority and privileges, to keep

control over that large area over which he held sway, he had to maintain

a large army to enforce his will. 31 To that end he needed all the revenues

of Dagestan plus, at the end of the seventeenth and the beginning of the

eighteenth century, the subsidy from the shah, which seems to have risen

from 700 tumans in 1687, to 1,700 around 1715 and up to 4,000 tumans by

1722. These subsidies were given so that the Shamkhal could pay his troops

and ensure their subsistence and thus induce them not to go marauding to

27 Gärber 1732, p. 36.

28 Bakikhanuf 1970, p. 164.

29 Gärber 1732, p. 35; Bahoud 1780, vol. 4, p. 118; Bedik 1678, p. 338 (pro absoluto Domino suo agnoscunt Persarum Regem). The Shamkhal sometimes received an appoint¬

ment and presents from the Russian court

(Gärber 1732, p. 36). The term also could de¬

note the Shamkhal of Tarku as was the case in 1559 (Bushev 1976, p. 41, n. 18). The use of the term in the meaning of 'heir apparent' perhaps is

alater development, i.e., after 1640, when the Shamkhalate was limited to the Tarku-Buynaq-Enderey region.

30 Le Bruyn 1737, vol.

1,p. 143 refers both to the titles and the names of the chiefs of four jurisdictions, to wit: the Shamkhal of Tarku, the Qrim Shamkhal of Enderey, the chief of Buynaq? (Beki) and Qara Budakh Beg, the chief of the district of Qara Budakh (awls of Gubden and Gurbuki), which was peopled by the Darghin, who originally also were part of the Qomuq federation under the Shamkhals.

31 This was still the case in 1825, when the Shamkhal also had trouble imposing his will on

his people. "He

isfortunate that of his eight and twenty villages always

afew remain loyal to

him and with the help of these he is always able to restore order." (ElCHWALD 1834, p. 85).

complement their income, krusinski rightly commented, "though in Truth

they only pay'd them as a sort of Tribute, by which they purchased the Peace,

and Security of their Subjects against the Enterprizes of the Barbarians." 32

Tahmasp Khan (i.e., the later Nader Shah) consciously followed the same

policy after he had subdued the Lezgis in 1734. In exchange for supplying

700 men the chiefs of Dagestan received 7,000 tumans in cash. 33

This suggests, as stated in the Encyclopedia of Islam, that the Shamkhals

"acknowledged Persian sovereignty throughout their existence, in spite of

their strong diplomatic ties with Russia in the late sixteenth century when

Russia was attempting expansion into Daghistan," which is not entirely cor¬

rect. First, it would seem that formal submission of the Shamkhals only took

place after 1547, for despite the existence of friendly relations between the

Safavids and the Shamkal (Tahmasp I married one of the Shamkhal's daugh¬

ters; see above) there is no evidence, as yet, that they acknowledged the Safa¬

vids as their suzerain during the first half of the sixteenth century. Also, the

authors of the Encyclopedia of Islam article contradict themselves, by stating

in the next line that the Shamkhals were vassals of Russia. However, Russia's

first contacts with the Qomuq only date from 1559, when Aghim, prince

of the Qomuqs of Tumen, became her vassal. Further Russian advances in

1586, 1594 and 1604 were all defeated by joint Qomuq, Crimea Tartar (Ot¬

toman) forces. Due to the split in the reigning family at the beginning of the

seventeenth century and fraternal discord at the beginning of the eighteenth

century, various Shamkhals swore allegiance to Russia, while at the same

time being vassals of Iran. Moreover, the Shamkhals and all other Dagestani

chiefs rallied to the Ottoman cause when these invaded the Shirvan region

in the 1580s and in the 1720s. 34 In short, at one time or another, the Sham¬

khals swore loyalty to all three of their large neighbors, when it suited them

and if it did not then they just ignored their presumed allegiance or switched

it to another party.

Being a vassal also meant that, in return, loyalty and submission had to be

shown in some concrete manner. The Shamkhal, therefore, each year, at least

in the early eighteenth century, sent a representative with two cow hides and

two sheepskins to the Safavid court troops as a symbolic annual token of his

32 Krusinski 1970, vol. 1, p. 243 (1,700 tumans)-, Gärber 1732, p. 33-34 (4,000 tu¬

mans}', Lavrov 1980, p. 103 (20,000 rubles); Bedik 1678, p. 338 (cui proinde & militia sua deserviunt, & invicem quotannis pro Regia munificentia muneribus donantur). That

Krusinski was right is clear from a report by the Jesuits in 1687, which relates that a few

years earlier, when payments had not been made, the Shamkhal had allowed caravans to be attacked. N.N. 1780, p. 35 (the annual subsidy was 700 tumans or 35,000 'abbasis in 1687).

33 Mervi 1369/1990, vol. 1, pp. 430-431.

34 Barthold/Kermani 1986; Klaproth 1814, pp. 174-176, 178; Eichwald 1834, p. 84.

vassalage. 35 Moreover, troops had to be provided to the governor of Shir-

van, when needed, such as in 1653, when Safavid troops, assisted by Sorkhab

[Sorkhey] Shamkhal governor (hakem) of Dagestan, 'Abbasqoli Khan Usmi,

and the people of Zakhur, etc., marched against a Russian fort built at Quyin

Su and destroyed it. 36 This was an occasion in which the Shamkhal and his

allies willingly participated as they were dead set against the construction

of any fortress near, let alone in their region. Time and again the Dagestanis

had opposed plans, by whomever it was (Russian, Safavid, Ottoman), to

build forts in their region. For example, Ma'sum Khan, the governor ( vali )

of Tabarsaran with 2,000 men opposed the construction of a fort at Shab-

eran in 1614/1615 and, although defeated, he was pardoned by Shah 'Ab¬

bas I (r. 1587-1629). A similar event occurred in 1658/1659, when Abbas II

(r. 1642-1666) gave orders to suppress the usurpation of Ologh Beg against

the Usmi that he had appointed. In addition to troops from the governor

of Shirvan, those of Dagestan, Zakhur, and Tabarsaran had to contribute

troops. The Dagestanis did not comply, however, and instead of supporting

the operation they opposed it. T : reason was that the Safavid governor had

orders to construct a fort that would serve as check on any future rebellion.

Thus, the 15,000 men Safavid army with cannons and musketeers was op¬

posed by a 30,000 Dagestan army led by Sorkhey Khan Shamkhal, Ologh

Beg (the usurping Usmi), Qeral Alb of Enderey and other leaders of Dag¬

estan, Qeytaq, and Enderey. T sy were defeated and the Shamkhal repented

his actions, which was accepted. His son Gol Mohammad Khan went to

the Safavid court with his sword around his neck, where he was pardoned,

received a robe of honor and was returned. 37

The nuisance value of the Usmi and the Shamkhal was quite clear to the

Safavid court and that was also the reason why, even after a rebellion, hon¬

ors were bestowed upon their representatives sent to court. 38 It is noticeable

that neither the Usmi nor the Shamkhal, with one or two exceptions, ever

went to court in person, but only dealt with the royal court at arm's length.

To ensure their loyalty they not only received subsidies, but they also had

to supply hostages (sons or brothers) who had to stay at the Safavid court.

The Shamkhal was held in respect at the Shah's court. According to Gärber,

formerly (he wrote after the fall of Isfahan in 1722) there were always four

35 Riyahi 1368/1989, p. 83.

36 Valeh Qazvini 1380/2002, p. 510; Vahid Qazvini 1383/2004, pp. 536-537. They

also assisted Rostam Khan, the Safavid sepahsalar in his Caucasus campaign against the Ottomans in the 1630s.

37 Vahid Qazvini 1383/2004, p. 173; Valeh Qazvini 1380/2002, pp. 632-638, 645; Baki- khanuf 1970, pp. 119-120; Monajjem 1366/1967, p. 355; Monshi 1350/1971, vol. 2, p. 787.

38 Gol Mohammad Khan b. Sorkhey Khan Shamkhal came to court and received robe

of honor. Valeh Qazvini 1380/2002, pp. 620.

seats to the left and right of the shah's throne. One was for the khan of

Qandahar, who protected Iran against India; the second for the Shamkhal

who protected Iran against Russia; the third one for king of Georgia who

protected Iran against the Ottomans and the fourth was for the khan on the

Arab borders. 39 Although entertaining, this story is not borne out by the

facts, but it nevertheless highlights the special position that both the Usmi

and Shamkhal occupied within the Safavid administrative hierarchy as re¬

lated by the Dastur al-Moluk, a Safavid state manual, which states:

[The right of] presenting requests of the Shamkhal , who is the governor of

Daghestan, as well as of the Usmi , which is also an office in Daghestan, also

belongs to the qurchi-bashis. When representatives and associates [of the

Shamkhal and Usmi\ come to the Exalted Court, the qurchi-bashi assigned a

host ( mehmandar ) to them, presented their requests to H.M., saw to the im¬

plementation of the decisions and decrees issued as a result, received the grants

presents for them from the khassah department and sent these to them. 40

The fact that these two rulers were singled out for this special treatment

and by no less than by the highest ranking emir of the Safavid kingdom

underscores their importance. The Shamkhals were also held in great re¬

spect locally as evidenced by the fact that people swore by "the head of the

Shamkhal". 41

Chronology and List of Shamkhals

In this section I list each Shamkhal, his name, the (approximate) dates of his

rule as well as, where possible, a brief discussion of the most salient points

of his years in power.

1. Badr is the first chief of the Qomuq mentioned, who lived in the four¬

teenth century. 42

2. An unnamed Sheykal (sic; Shevkal) is mentioned in 1396. 43

3. Mohammad or Mohammad Ghazi is mentioned as Shamkhal in the 1470-1480S. 44

4. Ghazi-Soltan b. Mohammad is mentioned in 1500-1501 as Shamkhal. 45

39 Gärber 1732, p. 35.

40 Mirza Rafi'a 2007, p. 21.

M Bérézine 1852, p. 77; Bérézine 2006, p. 64.

42 Lavrov 1987, p. 130.

43 Lavrov 1987, p. 130; Lavrov 1980, p. 107.

44 Lavrov 1987, p. 130.

45 Aytberov 1995, pp. 246-250; Lavrov 1987, p. 130; Lavrov 1980, p. 107.

5. Usmi [?], who may have been the chief of the Qomuqs in the first decade of the

16th century. 46

6. Ulahay I (Ulhay; A.l.kh; Arkhi; Orkay) was Shamkhal around 1510. 47 7. Ulahay II b. Ulahay I (ca. 1510-1550) was Shamkhal for about 40 years.

Undoubtedly, he was the same as "Shevkal Kara Musal, who probably was Ulkhai II or perhaps Bagday. His daughter became the second queen of Levan of Kalheti in 1529." 48 He may have been the Qrim Shamkhal, who helped Elqas Mirza, Shah Tahmasp's rebellious brother, escape to Istanbul in 1547. 49

8. Buday I b. Umal-Mohammad b. Usmi (ca. 1566-1567) is mentioned as Shamkhal. One of his sons was 'Ali Beg. However, it was his other son, 50 9. Sorkhey I b. Buday I (ca. 1572-1572) who succeeded his father as Sham¬

khal. Probably he had another brother Soltan Mahmud who resided in En- derey. 51

10. Chuban I (1574-1575) 52 was ruler over the Qeytaq, Kur, Avar, and the Cherkes until the ;rek River and the sea. When he died in 1575 his realm was reported to be in total disorder. His kingdom was divided among his

sons, Eldar in Buynaq and Tarkhu [Tarki], Mohammad in Qazanesh, Andi in Kafer-Qomuq and Geray in Hell. After that division the future Shamkhals came from these four families, according tc :heir age and competence and ruled these lands. After 1773 the position oi Shamkhal remained in the family of the Enur of Buynaq.

53Other children included a daughter, who was mar¬

ried to ahmasp I and who was the mother of Pari Khanom. The latter played an important role in determining her father's successor. Another son was Shamkhal Soltan Cherkes, who was killed in 1579 as was Pari Khanom, for being on he wrong side of Safavid court po tics in Qazvin, while yet anotl r son Emamqoli Khan escaped the killings and remained in Safavid service. 54

46 Lavrov 1987, p. 130; Lavrov, 1980, p. 107.

47 Lavrov 1987, pp. 130; 107.

48 Allen 1972, vol. 2, p. 593; Bérézine 2006, p. 294.

49 Qomi 1363/1984, vol. 1, p. 319; Rumlu 1357/1978, p. 415 (Qrim Shamkhal and Qowm Shamkhal); Monshi 1350/1971, vol. 1, p. 70; Jonabadi 1378/1999, pp. 507-508 (Qowm Shamkhal); Shirazi 1369/1990, p. 96; Budaq Qazvini 1999, p. 114 (via the lands of the Shamkhal).

50 Lavrov 1987, p. 130; Lavrov 1966, p. 211; Lavrov 1980, p. 107.

51 Lavrov 1987, p. 130; Lavrov 1966, p. 212; Lavrov 1980, p. 107.

52 Lavrov 1987, p. 130; Lavrov 1980, p. 107.

53 Bakikhanuf 1970, p. 109.

54 Allen 1972, vol. 2, p. 594; Monshi 1350/1971, pp. 95, 133, 192-195, 205-106,

224-126; Monajjem 1366/1967, pp. 24-25, 28-29.

Break-up of the Shamkhal dynasty

Most significant and serious was the conflict that broke out between the sons

of Chuban Shamkhal, for this led to the break-up of the realm of the Sham-

khalate. The first loss of land occurred when Chuban I's other son, named

Soltan Bud (or But), who was not in the line of succession, because he was

not born to a noble woman (his mother was the daughter of Uzun Cherkes),

demanded his share. With the help of the Cherkes he fought his brothers and

forced them to cede to him "all the lands between the Sulaq and the Terek

as well as lower Machgach and the district of Salatav until Mount Kerkhi,

which is the border of Gonbet. He gathered the Qomuq tribe around him

and settled them in Chelyurt." After having expelled the Russians across the

Sulaq in 1604, "Soltan Bud with his tribe settled in Enderey. All the Qomuq

emirs are from the line of his sons Aytmut and Qazan Alp." 55

The other brothers at first collaborated to put an end to the Russian ac¬

tion to build a fort on the Sulaq in 1594. However, soon thereafter the frater¬

nal unity broke apart. Andi Beg together with his brother Soltan Mahmud,

who resided in Endery, fought against their two other brothers Eldar and

Geray. 56 As a result of this conflict two branches of Shamkhals came into

being. One branch based in Tarku, which line would continue as that of

the Shamkhals of Tarku. The other branch was based in Qazi-Qomuq and

would effectively break away from the Shamkhalate, for after 1641 they are

not mentioned anymore as Shamkhals.

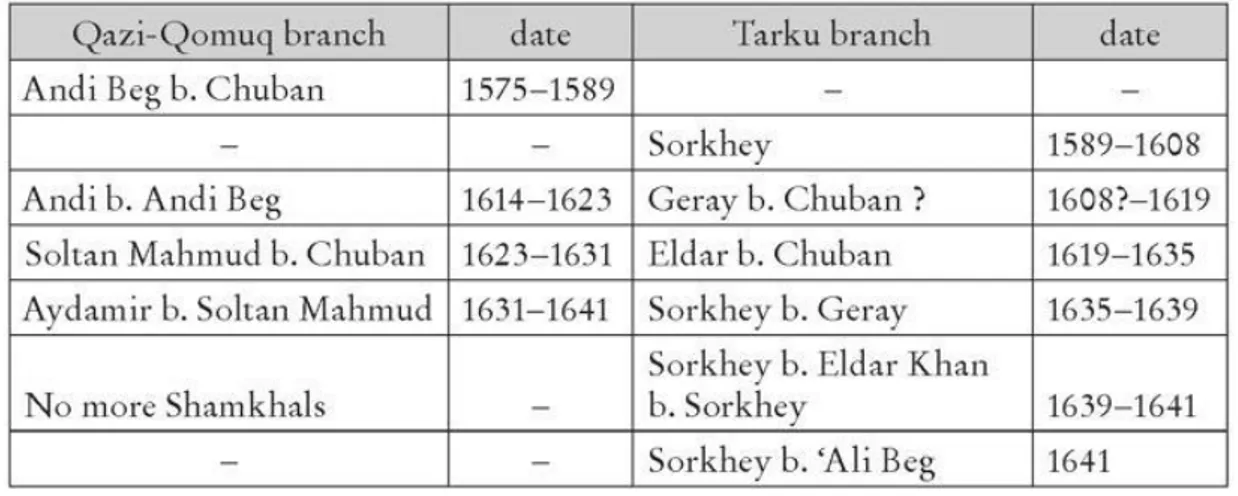

In Table 1, 1 have tried to show whom of the Shamkhals belonged to which

branch of the family. As is clear from Table 1 it is not known who the im¬

mediate successor of Andi Beg was, unless it was Sorkhey, but it is unknown

to whom he was related in the Shamkhal family. This makes it difficult to

explain why he and not Andi Beg's brother Geray was the Shamkhal. More¬

over, the position of Geray is not entirely clear either. He is mentioned a few

times as Shamkhal, but this situation conflicts with the position of Sorkhey

as Shamkhal. Nevertheless, I have placed Sorkhey with the Tarku branch,

because it is reported that Soltan Mahmud attacked him. Finally, we still do

not know who was Shamkhal between 1608 and 1614. Following Table 1, I

first list the Shamkhals of the Qazi-Qomuq branch, which ends in 1641 and

then continue with the Shamkhals of the Tarku branch.

55 Bakikhanuf 1970, pp. 109-110.

56 Bushev 1976, pp. 298, 370 and index; Lavrov 1966, p. 212.

Table 1: Shamkhals of the Qazi-Qomuq and Tarku branch

Qazi-Qomuq branch date Tarku branch date

Andi Beg b. Chuban 1575-1589

- -- -

Sorkhey 1589-1608

Andi b. Andi Beg 1614-1623 Geray b. Chuban ? 1608?-1619

Soltan Mahmud b. Chuban 1623-1631 Eldar b. Chuban 1619-1635 Aydamir b. Soltan Mahmud 1631-1641 Sorkhey b. Geray 1635-1639 No more Shamkhals

Sorkhey b. Eldar Khan

b. Sorkhey 1639-1641

- -

Sorkhey b. 'Ali Beg 1641

The Qazi-Qomuq branch

11. Andi Beg (1575-1589) succeeded his father Chuban I as Shamkhal. 57

When Andi Beg became Shamkhal, the alliance between Kakheti and the

Shamkhal that had existed in much of sixteenth century under king Le¬

van changed into a feud under his son Alexander, due to the latter's actions

against his half-brothers, sons of the U ihay II Shamkhal's sister. 58 How¬

ever, things are always more complicated in the Causasus, for Alexander

had allies among the Shamkhal's family, such as "Krym Shevkal, a cousin-

germain of Andi Soltan Shevkal, who probably was a brother's son of Chu¬

ban Shevkal. He was an ally of Alexander II of Kakheti and was given the

apanage of Elisu. His daughter married Alexander's son Giorgi." 59 In 1586,

Alexander asked Russia for support against the Shamkhal, who had invaded

his country, and, in 1594 a 7,000 strong Russian force built some forts in

Qomuq territory and attacked Tarku. This led to a joint operation by the

sons of Chuban, who destroyed the fort and expelled the Russians. 60

12. Andi, son of an unnamed Shamkhal (1614-1623), who was said to have

ruled in 1589, which suggests that his father must have been Andi Beg

Shamkhal. This is confirmed by a 1614 report from Terki that states that the

Shevkal was a son of Andi. He resided in Qazi-Qomuq and had a son called

Ali Soltan. In 1615, an attempt to make peace between Soltan Mahmud and

57 Bushev 1976, pp. 298, 370 and index; Lavrov 1966, p. 212.

58 Allen 1932, pp. 140, 150, 152,164.

59 Allen 1972, vol. 2, p. 594.

60 Baddeley 1908, pp. 8-9; Allen 1972, vol. 2, p. 594.

Geray failed perhaps because Geray awaited a favorable reply to his request

for support from Moscow, after he and his brother Eldar had sworn alle¬

giance to Russia. This may also explain why, in 1617, Andi Shamkhal com¬

municated to Moscow that he wanted friendly relations, because his un¬

cles Geray and Soltan Mahmud continued with hostile action against him. 61

There are no further particulars known about him.

13. Soltan Mahmud [Mahmut] (1623-1635) is mentioned as 'the prince of

the mountains,' and he, therefore, was the Shamkhal in Qazi-Qomuq. For

"his brother Ildar Khan, brother-in-law of the Shah, whom they call the

Crimean Shah, resided at Tarki, which was peopled by Kumyks, who were

called subjects to the Shah." From the designation Crimean Shah or Qrim

Shamkhal it is clear that Eldar was the Shamkhal at Tarku. 62 Another Soltan

Mahmud was the son of Andi Soltan Shevkal by a daughter of Soltan Ah¬

mad, Usmi of Qara-Qeytaq, who probably was the person that olearius

met in 1638 and later described. 63

14. Aydemir b. Soltan Mahmud of Enderey (1635-1641) was the last Sham¬

khal of the Qazi-Qomuq branch, for when Sorkhey Mirza (the Shamkhal

of the Tarku branch) died in 1640 no new Shamkhal was appointed for the

Qazi-Qomuq region. Aydemir's mother was the daughter of the Karbardin

lord Alkhas Sholokhov. Aydemir had been a hostage at Terki in 1615, and

he himself sent his sons Aydemir, Qazan Alpa and, in 1634, his one-year old

son Tochelov as a hostage. In 1626 he had sworn allegiance to Russia. 64

61 Lavrov 1987, p. 130; Lavrov 1980, p. 107; Lavrov 1966, p. 212.

62 Kotov 1958, p. 34; Kemp 1959, p. 6. Although the term Qrim Shamkhal also could designate the heir apparent, in certain instances it was used to refer to the Shamkhal at Tarku. For an earlier example see Bushev 1976, p. 41, n. 18.

63 Allen 1972, vol. 2, p. 594. Probably he was the other Shamkhal that Olearius referred to as 'Suithan Mahmud', who resided at Enderey. It is odd that Olearius men¬

tioned him, without any explanation, as he earlier had reported that the Shamkhal's name was Sorkhey, whom he had met in person. In fact, when asked about him, Sorkhey told the Holstein ambassador that Soltan Mahmud was untrustworthy, which seems to indicate that the relationship between the two branches of the family while not friendly was not utterly hostile anymore. This is also indicated by the fact that Soltan Mahmud, seemingly without any fear of attack by Sorkhey Shamkhal, came twice in person to see the Holstein

ambassador and even organized

ameal for the embassy. Olearius left us

adescription of him and of the banquet that he gave

(Olearius 1971, pp. 733, 735, 737).

64 Favrov 1966, pp. 213-214.

The Tarku branch

15. Sorkhey II Shevkal (1589-1608) is the next Shamkhal mentioned. 65 It is

not known to which of the other Shamkhal family members he was related;

it is most likely that he was Chuban I's brother or brother's son. However, he

must have belonged to the Tarku branch. For in 1597 Russian sources men¬

tion that Soltan Mahmud, the brother of Andi Beg gave battle to "Shevkal

Surkay". In 1603 it was reported that he spent most of the year in Qazi-

Qomuq. 66 T1 s seems to contradict him belonging to the Tarku branch.

However, this means that this Shamkhal still had control over that part of

his realm, but that his successor had not, for later Sorkhey III held Qazi-

Qomuq, where he died in 1640 (see below). This suggests that control over

the Shamkhal's lands was fluid, which explains the regular battles between

the two branches of the family.

When in 1606, Shah 'Abbas I retook much of the Caucasus from the Ot¬

tomans the Dagestan chiefs reluctantly submitted to the Safavids. In 1578

they all had declared for the Ottoman Soltan, following the Shamkhal's lead.

It was, therefore, that "One of the clauses of the peace treaty between the

Safavid and the Ottoman states concluded in 1021/1612 stipulated that the

Shamkhal and the other princes loyal to the Porte would not suffer any re¬

prisals on the part of Persia." 67 In 1607, Sorkhey sent several of his relatives

to welcome Shah Abbas I on his return to Shirvan and pay him homage.

Since one of them was his brother Elqas Beg, it would seem that Sorkhey

was the son of Geray Khan (who also had a son called Elqas), but that is

highly unlikely as Geray rather than Sorkhey would have been Shamkhal. 68

Shah Abbas I wanted to cement good relations with the powerful Qomuq

chief and, therefore, in that same year, he concluded a temporary marriage

with the daughter of Sorkeh (sic) Shamkhal. 69 However, in 1608 it is already

reported that Sorkhey II was seeking assistance from the Ottomans against

Iran and Russia, but before this could lead to anything he died. 0

16. Geray Khan Shamkhal (159?-1619), Andi Beg's brother. He has opposed

his brother's election as Shamkhal, although he does not seem to have for¬

mally claimed to be Shamkhal at that time. The brothers had acted jointly

65 Bushev 1976, pp. 425-426.

66 Lavrov 1966, p. 212.

67 Barthold 1965.

68 Lavrov 1980, p. 107; Monajjem 1366/1967, pp. 325 (Elqas Beg, the brother of the Shamkhal and Khalil Beg, the son of the Shamkhal), 356 (Khalil Beg, son of the Shamkhal of the Qomuq was killed by the Qomuqs).

69 Monajjem 1366/1967, p. 324 ('aqd-e monqate').

70 Lavrov 1966, p. 212.

against the Russian threat in 1594, but thereafter the fraternal unity broke

down. Andi Beg together with his brother Soltan Mahmud, who resided in

Endery, fought against their two other brothers Eldar and Geray. 71 Prob¬

ably to get Iranian support (at that time the Sorkhey Shamkhal backed the

Ottomans), Geray Khan had contacts with Shah 'Abbas I, for in 1599 he

sent his son Elqas to the Safavid court. 72 Apparently, the Iranian contacts

were not encouraging, for Eldar, who resided at Tarku in 1603 together with

other Dagestani chiefs sent presents to Tsar Boris Godunov (r. 1598-1605). 73

Despite this friendly gesture, Geray Khan is reported to have attacked three

forts the Russians had built at Tarku [Tarki], Enderey and at a third un¬

known place in 1604, together with his half-brother Soltan Bud and the

Crimean Tartars. After much fighting, the Russian garrisons saw no other

way out than to come to an agreement with the enemy and withdraw to

Russian territory. But because the Qomuq wanted to make them prisoner,

which was contrary to the agreement, the Russians started to fight and they

were all killed. 74 In 1612, Geray Khan is mentioned as the Qomuq chief

of Enderey. In 1614 he contacted Russia for support and together with his

brother Eldar pledged his allegiance to Tsar Mikhail I (r. 1613-1645). 75 After

Geray's death in 1619

17. Eldar Shamkhal (1619-1635) succeeded his brother Geray. 76 In 1614, he

and Geray had sworn allegiance to Moscow, and, as a sign of their loyalty,

he had sent his son Amir Khan as a hostage to Terki. They had hoped to get

Russian support against Andi Shamkhal and Soltan Mahmud of Enderey.

They also bolstered their position with Iran. For in that same year their sis¬

ter married Shah Abbas I; hence kotov's remark that Eldar was the shah's

brother-in-law. To capitalize his Russian connection with a view to shore up

local support, Eldar asked Moscow not to impose duties on goods brought

for sale in Terki. To discuss further development of the relations with Mos¬

cow he sent his son Amir Khan there in 1621 as his envoy. In 1623, probably

as a result of this mission, Eldar was appointed Shamkhal by Russia. This

required a delicate balancing act between Iran and Russia, as he also was the

shah's son-in-law and vassal. In 1626, Eldar used this situation to ask Russia

for favors, in particular the waiving of customs duties on exports. In 1632,

the Usmi of the Qeytaq made an unsuccessful effort to reconcile Eldar and

Soltan Mahmud. In 1634, Eldar wanted to march against Soltan Mahmud

71 Bushev 1976, pp. 298, 370; Lavrov 1966, p. 212.

72 Monajjem 1366/1967, p. 193 (Elqas valad-e Shamkhal-e Lezki).

73 Lavrov 1966, p. 213.

74 Bakikhanuf 1970, pp. 110-111; Gärber 1732, p. 29-31.

75 Bushev 1987, pp. 57, 65; Lavrov 1966, p. 213.

76 Lavrov 1987, p. 130; Lavrov 1980, p. 107.

assisted by Russian forces. However, he died in June or July 1635. Immedi¬

ately preparations were made for the election of the new Shamkhal. 77

18. Sorkhey Khan III Shamkhal b. Geray Khan (1635-1639) was appointed as

governor < Dagestan, which shows that by then, like the Usnn of the Qeytaq, Shamkhal had become a cog in the Safavid administration and that each new Shamkhal had to be coi irmed in his position by t e shah. According to Olearius, he was 38 years old in 1638 and was related to the shah, with whom he had good relations and on whom he could rely for military support

against opposition om within Dagestan. He had several relatives living with him, amongst whom an 18-year old nephew Imam Mirza, who was in charge of part c Tarku. He was his brother's son and apparently Sorkhey had denied him his right to rulership and was plotting to take his life. 78

19. Sorkhey Mirza IV, son of Eldar Khan, son of Sorkhey Shamkhal

(1639-1640) became the new Shamkhal, the Emir of the Qomuqs, in the

year 1639. In the previous year, Tsar Mikhail had already confirmed him in the position of Shamkhal. Sorkhey died in Qomuq in 1640, which was the former capital of the Shamkhals and their heir-apparents. According to Bakikhanuf, nobody immediately replaced him, because initially the Qazi-Qomuqs through the intermediary of his deputy continued to pay the Shamkhal's fixed tribute, but eventually they rebelled and as of that time the Qazi-Qomuqs became independent of the Shamkhal. Elqas Mirza, the brother of Sorkhey Mirza, who had been sent as hostage to Shah Safi I's (r. 1629-1642) court received the title of Safi Qoli Khan when he was gover¬

nor of Shirvan and Erevan. 79

20. Sorkhey V b. 'Ali Beg (1641). 80

21. Sorkhey VI b. Geray of Tarku (1642-1668). His sons were "Geray, Kel-

mamat-Mirza, Kazbulat", and Gol Mohammad Beg. 81

77 Lavrov 1966, p. 213.

78 Valeh Qazvini 1380/2002, pp. 242-243; Vahid Qazvini 1383/2004, p. 278;

Olearius 1971, pp. 729, 732. Sorkhab [sic] Khan Shamkhal, when he was at court, such as in August 1635 in Ardabil, he was one of the shah's boon companions ( Astarabadi 1364/1985, p. 254) and was sent home with presents and a robe of honor

(Yusof/Monshi 1317/1938, pp. 192-193; Esfahani 1368/1989, p. 238).

79 Bakikhanuf 1970, pp. 122-123. For more information on Elqas Mirza, who was the grandfather of Fath 'Ali Khan the grandvizier, see Matthee 2004, pp. 182-183.

Bakikhanuf implies that the break with the Qazi-Qomuq took place after the death of Sorkhey Mirza, but Olearius 1971, p. 729 mentions that these already had a separate chief in 1638.

80 Lavrov 1987, p. 130; Lavrov 1966, pp. 213-214.

81 Lavrov 1980, pp. 102; Valeh Qazvini 1380/2002, pp. 620, 626, 633, 638, 644-645.

22. Chuban II was Shamkhal in 1668, but no particulars are known about his rule. 82

23. Buday II (1668?-1688). According to Russian scholars, the following

Shamkhal was not Buday II, but rather Mahmud, who is mentioned by Ev-

liya Chelebi in 1672. These same authors have Buday II succeed him only

in 1682. 83 However, in Dutch archives there is a royal command from Shah

Soleyman, dated Dhu'l-Hejjah 1081/April-May 1671, addressed to Buday

Shamkhal, ordering him to release a number of enslaved Dutchmen who

had been ship-wrecked on the coast near Darband, amongst whom the well-

known traveler Jan Struys. 84 This makes it likely that Buday II succeeded

Chuban II rather than Mahmud. The latter either is an erroneous notation

(Evliya Chelebi's information is erroneous in other instances), or he mistook

a brother or other relative called Mahmud for the Shamkhal.

24. Morteza 'Ali Shamkhal (1682-1699) succeeded his father; about his rule

nothing is known. 85

25. Geray Khan Shamkhal (1699-1717) is mentioned as Qomuq ruler in

1712. 86 He supported the Safavid government against the marauding I mi

and other Caucasian chiefs. His rule probably started in 1699, when "Keday

Khan [sic; Geray Khan] was appointed to the dignity of Shamkhal of the

province of Dagestan (liva-ye Shamkhali-ye velayat-e Daghestan)". 87

26. Omalat (Chuban Shamkhal) (1717-1719) was his successor. Probably,

he is the same as Molat ('Umalat) Shabkal, the son of Morteza Ali Shamkhal.

His rule had been opposed from the beginning by his brothers Morteza Ali

and Adel Geray. Omalat lived in Tarku, but in 1718 moved to Qazanesh. 88

According to Berezine , by 1842 the title of Chuban Shamkhal (the Shep¬

herd Chamkhal) indicated a different branch of Qomuq chiefs, just as that

of Qrim Shamkhal, and that Omalat Chuban Shamkhal was the first of this

particular branch. 89

82 Lavrov 1987, p. 130.

83 Lavrov 1980, p. 102; Lavrov 1987, p. 130.

84 Nationaal Archief, VOC 1274, f. 752 (April-May 1671).

85 Lavrov, p. 130; Lavrov 1980, p. 102.

86 Bakikhanuf 1970, p. 127; Lavrov 1987, p. 130; Lavrov 1980, p. 102.

87 Nasiri 1373/1995, p. 273.

88 Gärber 1732, pp. 38-39 (Schubgan Schamchal); Lavrov 1980, pp. 103-104; Lavrov

1987, p. 130.

89 Bérézine 1852, p. 78; Bérézine 2006, p. 65.

27. 'Adel Geray b. Morteza 'Ali Shamkhal (1719-1725) was the next Sham¬

khal, who, in Russian reports, is called Abdol-Geray. 90 Although Shah Sol-

tan Hoseyn (r. 1694-1722) had appointed Omalat as Shamkhal, his rule was

opposed by his two brothers Morteza Ali and Adel Geray. Morteza Ali

also claimed to be Shamkhal. In 1717, he went to Terki, pledged allegiance

to Peter I and tried to get Russian support against his younger brother. The

Astrakhan government was favorably disposed to his request, but he was

sent to Russia with his two sons. It is not known why the Russians changed

their mind, but perhaps Adel Geray had made them a better offer. 91 The

latter had argued that his brother was pro-Safavid, which he claimed not to

be. Adel Geray had to send his son Khass Bulat to Terki as a hostage. Later,

in his stead, Eldar son of Morteza Ali Shamkhal went. 92 With Russian help

Adel Geray was then able to oust Omalat as well as through contacts at the

Safavid court to have Shah Soltan Hoseyn confirm him as Shamkhal, 93 and

to continue to pay the Iranian subsidy of 20,000 rubles per year like he did

to his predecessor. The ousted Shamkhal acquiesced in his defeat and Adel

Geray awarded him a small district between Fort Holy Cross and Aray, ac¬

cording to colonel Gärber , who commanded part of the Russian invasion

troops in 1722. The defeated Shamkhal then allegedly became known as

Chuban Shamkhal (Schubgan Schamchal), which, in Turkish, means 'peas¬

ant or cattle herder', because, instead of lording it over the whole of Dagestan,

he only was lord over a few peasants. However, Lavrov has argued that the

term "Shobhan" has been derived from the Arabic word shubha, meaning

'obscurity, doubt, dubious', thus meaning the 'Obscure Shamkhal'. The lat¬

ter must have enjoyed this accolade, if ever he did, for a very short time, for

in a letter to Peter I dated 1720, he is referred to as the late Shamkhal. 94

'Adel Geray did not take advantage of the troubles in Iran. 95 In fact, when

Ahmad Khan Usmi and Sorkhey and others marched to capture Shamakhi,

Geray Khan Shamkhal came to oppose them and sent a message that "I am

the servant of the government of Iran. If you go to Shamakhi I will take

your country." Therefore, Ahmad Khan remained behind to protect his

90 Lavrov 1987, p. 130; Lavrov 1980, pp. 102-103 (he was referred to as the son of Bu- day Shamkhal in one source, but two other sources state that he was the son of Morteza 'Ali); Gärber 1732, p. 38; Klaproth 1814, p. 196.

91 Lavrov 1980, p. 105 (his brothers were Kas Bulat Beg, Aldi Geray, and Kulemet Beg or Molat ('Umalat) Shavkal, who lived in Enderey); Bushev 1978, pp. 207, 209, 219.

92 Lavrov 1980, p. 104; Bushev 1978, p. 219.

93 These contacts included his kinsman, the grandvizier Fath Ali Daghestani b. Vah- shatu Soltan aka Alqas Mirza b. IldirimKhan Shamkhal (1715-1720). See Matthee 2004, pp. 179-220; Hedayat 1339/1960, vol. 8, p. 505.

94 Lavrov 1980, p. 103; Gärber 1732, p. 36.

95 Gärber 1732, p. 36.

own lands and Sorkhey and Hajji Davud with a contingent of troops of the

Usmi marched and after 15 days of siege with the help of the Sunnis of the

city captured the city in the year 1712. 96

When Peter I came to the Caucasus to take advantage of the internal trou¬

bles in Iran, 'Adel Geray subjected himself to Russia in 1722, but kept all

his privileges and rights. 97 Nevertheless, he was like a guilded bird kept in

a golden cage. "The Circassian prince, who resides here [Tarku], is allowed

five hundred Russians for his guard, but none of his own subjects are permit¬

ted to dwell within any part of the fortifications." 98 This must have caused

resentment, which was enflamed due to the construction of Fort Holy Cross

as well as by the golden promises made by the Ottomans. 'Omar Sham-

sadil Beg, one of 'Adel Geray 's sons, was in Shamakhi, whence Sorkhey of

the Qazi-Qomuq was in correspondence with the Ottomans. He asked for

troops against the Russians and the Ottomans promised troops by March

1724. At the same time, the Porte assured the Russians, who were worried

about these contacts, that it had not given or promised any aid to the agents

of Lezgi chiefs; it had only given room and board to them. 99 Edged on by the

Usmi, 'Adel Geray rebelled in 1725. He raised 30,000 men, but was defeated.

General Kropotov destroyed all his lands and his seat of government. 'Adel

Geray hoped for a pardon, which was promised, but when he came to the

Russian camp at Tunturkali he was arrested and sent to Kola in the Arch¬

angel region, where he spent the rest of his life. The fact that he had killed

his personal guard of 12 Russians may have played a role in this banishment.

Peter I abolished the post of Shamkhal, and gave its functions to the general

commanding the troops in Shirvan. 100

'Adel Geray 's main wife was a daughter of Soltan Mahmud of Aray, whom

he later appointed as his successor. 'Adel Geray had two brothers, Atazhuk

and Morteza 'Ali and three sons, Khass Bulat (Kambulat; Khass Fulad), Bu-

day and Sa'dat Geray (Sadat Kurei). 101 His oldest son succeeded him, al-

96 Bakikhanuf 1970, p. 127.

97 Gärber 1732, pp. 36-37.

98 Bruce 1970, p. 312. The same source (p. 317) described him as "the shafkal, or prince, of Tarku, the chief of the Dagestan Tartars". However, according to Gärber 1732, p. 36, he only had a Russian guard of one non-com, one drummer, and 12 soldiers who remained with him in Tarku until his rebellion.

99 Bournoutian 2001, p. 119,149.

100 Gärber 1732, pp. 15, 32, 36-39 (Abdulgierei); Hanway 1753, vol. 3, p. 234; Klap- roth 1814, p. 199; Bournoutian 2001, p. 119, 127; Bakikhanuf 1970, pp. 129, 137-138;

Lerch 1776, p. 473; Lerch, 1791, p. 30; Eichwald 1834, p. 85. According to two sources he was immediately succeeded by his son Khass Bulat or by his older brother Morteza 'Ali, but this is contradicted by all other evidence. Lavrov 1980, p. 104.

101 Lavrov 1980, pp. 104-105.

though not yet in a formal sense, and the land was divided between him

and some elders. Then the Usmi and Soltan Mahmud Aray tried to become

Shamkhal (a function that came with financial benefits from the Iranian shah

and the Russian tsar), but nobody was selected, and thus, Soltan Mahmud

of Aray's hope to the succession evaporated. The revenues of the Shamkhal

lands's were left in the hands of the elders, who had to send two hostages

to Fort Holy Cross. The Qomuqs thus remained without a Shamkhal from

1725 until 1734 when the Russians withdrew from the region, which they

returned to Iran by treaty. Many local rulers had submitted to Russia, which

bitter pill was sweetened by the fact that they were allowed to keep all their

revenues and did not have to contribute anything to the Russian treasury. 102

Adel Geray's son Khass Bulat, who resided at Buynaq, received 3,000 rubles/

year, but, according to the Russians, he was not to be trusted. He never came

to Fort Holy Cross, but instead sent hostages. 103

28. Khass Bulat (Khass Pulad, Khass Fulad) (1734-1757/1758), son of Adel

Geray Khan, son of Morteza Ali was confirmed in 1734 as Shamkhal of

Dagestan by the regent of Iran, Tahmasp Khan (the later Nader Shah), who

gave him robes of honor. The new Shamkhal promised to serve Iran, to

which Shirvan and Daghestan had been returned by treaty with Russia. Ini¬

tially, the Shamkhal supported Nader, for example, against the Avars and

others in 1735. Because of this he was met with opposition (see below), but

the opposition was of short duration as Khass Bulat seems to have had the

situation firmly in hand and had full control over his own realm. Not only

were his opponents unhappy with him, so was Nader Shah who in vain tried

to replace him in 1744, although later he was pardoned and was in attendance

to Nader's court. Khass Bulat continued to rule after Nader Shah had died.

Although the written sources disagree on the date of his death (1757/1758,

1760, 1764 and 1773 are mentioned), it is clear from his tombstone that he

died in 1757/1758, as L avrov has argued. 104

29. Eldar II b. Morteza Ali b. Buday II (1735) was appointed Shamkhal

by the Khan of the Crimea, 105 who, to support the Ottomans against Iran,

had marched into the Caucasus region, and, had entered the outskirts of

102

Gärber 1732, pp. 15, 32, 36-39 (Abdulgierei); Bournoutian 2001, p. 119, 127;

Bakikhanuf 1970, pp. 129, 137-138; Lerch 1776,p. 473; Lerch 1791 p. 30. According to Lavrov 1980, p. 105, he received only 150 rubles per year.

103

Lerch 1791, p. 30.

104

Bakikhanuf 1970, pp. 143, 146; Lavrov 1980, p. 104, 106; Lavrov 1987, p. 130; As- tarabadi 1368/1989, pp. 307, 336, 479; Astarabadi 1341/1962, p. 578; Eichwald 1834, p. 85.

105

Lavrov 1987, p. 130 (he is described âi the Qazanesh son of Morteza Ali, which

indicates that he was residing there); Astarabadi 1368/1989, p. 343.

Darband in that year. Eldar Khan, the usurper Shamkhal, the Usmi and Sorkhey of the Qazi-Qomuq gathered in Qazanesh with the intention to attack Khass Bulat Khan, the Shamkhal,

106but they were defeated.

30. Ahmad Khan Beg Jangtay (1744) was appointed Shamkhal by Nader Shah in 1744, because he was not pleased with the performance of Khass Bulat Khan. He therefore bestowed on Ahmad Khan Beg Jangtay the title of Salahshuri and Shamkhal as well as twenty purses of cash.

107However, t e new Shamkhal left with the Russian embassy of Prince Mikhail Mikhailov- ich Golitsyn, because he was afraid to be killed by the Lezgis as soon as Nader Shah would have left Dagestan. 108

31. Amir Khan Qazanesh Mohammad the Toothless aka Tishsiz-Bammat (Tishnek Mohammad) b. Geray of Bammatulin (1757-1758), was a sister's son of Khass Bulat, whom he had appointed as his successor, according to Lavrov . However, according to Bakikhanuf , Amir Khan Qazanesh op¬

posed Khass Bulat in 1757/58, because he treated his relatives so badly. With the help of the emirs of Enderey, Nowsal Khan b. 'Omnia Khan-e Avari and Amir Hamzeh Usmi he expelled him from Tarku [Tarki] and Buynaq and he became Shamkhal. However, Morteza Ali Shamkhal with the support of Fath Ali Khan of Qobbeh, the people of Quy-suybuy and the Aqusheh dis¬

trict, counter attacked and after one month Morteza Ali had re-established control. The toothless Shamkhal and after him his son Khass Bulat were satisfied with the governorship of Qazanesh. 109

32. Mehdi

Ib. Morteza Ali b. Buday II (1757-1758), who was the oldest family member o :he former Shamkhal and lord of Buynaq, was hailed as Shamkhal as soon as Mohammad the Toothless made his bid for power. According to Bakikhanuf

,Mehdi had been exiled to Astarabad. After Nader Shah's death he left Astarabad via Turkestan, where he obtained the support of the Qalmuq to oppose Khass Bulat Shamkhal. Near Qazanesh there was

afierce battle and he was victorious. Finally, he reached a truce with Khass Bulat Khan and, as before, he became the governor of Buynaq. He had two sons, Morteza All and Bammat (Mohammad). When Mohammad the oc bless claimed power, the sons of Mehdi rose to his defense and defeated the pretender. At a meeting at Qazanesh, Mehdi was proclaimed Shamkhal. But when it became known

106 Bakikhanuf 1970, pp. 146, 148.

107 Bakikhanuf 1970, pp. 155, 160; Mervi 1369/1990, vol. 3, pp. 1043-1044 (Ahmad

Khan Usmi-ye Lezgi-ye Jangtay); Astarabadi 1368/1989, p. 514.

108 Lerch 1776, p. 401.

109 Bakikhanuf 1970, pp. 164, 168, who wrongly calls him his brother's son. Lavrov 1980, pp. 105-106 (the son of Ulu Misei and Geray Beg of Bammatulin). For the genea¬

logical tree of the Bammatulin branch see N.N. 1868, pp. 53-80.

that he su ered from bad eye-sight the dignity of Shamkhal was transferred

to his o dest son Morteza 'All Khan with the full meeting's approval. The lat¬

ter defeated Mohammad the Toothless, who gave up his claim. 110

33. Morteza 'Ali b. Mehdi b. Morteza 'Ali (1758-1785), the sister's son of

Khass Bulat and the Emir of Buynaq, whom he allegedly had appointed as

his successor before his death. Morteza Ali's children were Buday, Sorkhay

Shamkhal, Soltan Murad and Mehdi Buynaqi. They received a pension of

1,250 rubles from Russia and also served as hostage for their father's good

behavior. 111

34. Bammat (Mohammad) (1785-1797), his brother, succeeded Morteza 'Ali.

Russia paid him 6,000 rubles "for the formation of a body of troops", con¬

firmed his title and position and provided him with a body guard. 112

35. Mehdi Beg, son of Mohammad Shamkhal (1797-1830), succeeded his

father. 113 In that same year he married Pari Jahan Khanom, the sister of the

late Fath 'Ali Khan of Qobbeh. He was the only Dagestani chief who did not

rebel, when in February 1806 general Tsitsianov was treacherously murdered

at Shushi. Major-general Mehdi Beg was rewarded for his loyalty with the

governorship of the Ulus districts with the title of Khan of Darband when

the Russian had retaken it in June of that same year. In 1824, he was described

as "though stripped of his authority by the Russians, is indulged by them

with the honorary rank of Lieutenant-general in their army, and with the

permission to retain the appellation of his ancestors". 114 He and many other

chiefs and their relatives had enlisted with the Russian army and had received

the rank of commissioned officer at a grade commensurate with their social

standing. This was the result of an imperial order of 1796, where the com¬

manding Russian general was ordered to do everything to ensure the loyalty

of the Shamkhal, the chiefs of the Qara-Qeytaq, Qazi-Qomuq and the Avars.

Money and gifts had to be given to them, while their sons and relatives had to

be encouraged to join the Russian army and be paid a salary. 115

110

Bakikhanuf 1970, p. 160; Lavrov 1987, p. 130.

111

Bakikhanuf 1970, pp. 164, 168; Lavrov 1980, pp. 105, 108; Eichwald 1834, p. 85.

112

Bakikhanuf 1970, pp. 168, 177; Lavrov 1980, p. 108; Lavrov 1987, p. 130; Klap- roth 1814, p. 208.

113

Lavrov 1987, p. 130; Lavrov 1980, p. 108.

114

Bakikhanuf 1970, pp. 179, 188, 190; Eichwald 1834, pp. 84 (the Shamkhal's 18- year old son was personally involved in maintating law and order and sentencing people to corporal and other punishment), 85 (the Shamkhal Mehdi Beg was about 60 years old).

115

Bournoutian 2001, p. 356.

36. Soleyman Pasha b. Mehdi II (1830-1836).

116 Keppel's description of the

Shamkhal in 1824 as "an unwieldy, red-bearded Tartar, with a forbidding

countenance" must have been of Soleyman Pasha, who was about 35 years

old at that time, born to his father's first wife, but not yet Shamkhal. 117

37. Abu Moslem Khan b. Mehdi II (1836-1860) was 36 years in 1842 and in

commom parlance was referred to as governor of Dagestan. His official ti¬

tles were: Shamkhal of Tarku, Vali of Dagestan, chief of Buynaq, lieutenant-

general Abu Moslem Khan. 118

38. Shams al-Din b. Abu Moslem Khan (1860-1867). 119

When the realm of the Shamkhals, who had but become administrators in

Russian service, was transformed into the Qomuq sub-district (okrug) of

Dagestan province there was no more need for them and their function was

abolished in 1865, and thus a long tradition came to an end.

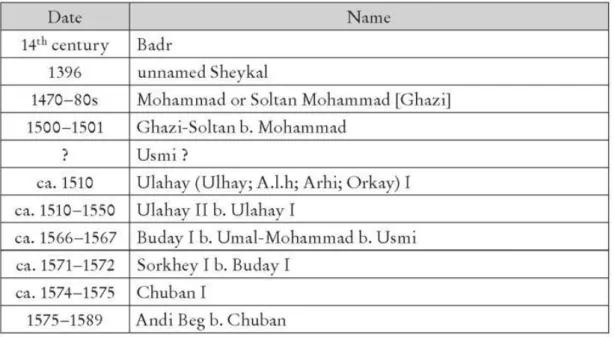

Although the Shamkhals have been discussed and listed above, for easy

reference I have included Table 2, which summarizes the above discussion.

Table 2: List of names and dates of known Shamkhals (ca. 1350-1867)

Date Name

14th

Cen tU1-y

Badr1396

unnamed Sheykal

1470-80S

Mohammad or Soltan Mohammad [Ghazi]

1500-1501

Ghazi-Soltan b. Mohammad

? Usmi ?

ca. 1510

Ulahay (Ulhay; A.l.h; Arhi; Orkay) I

ca. 1510-1550

Ulahay II b. Ulahay I

ca. 1566-1567

Buday I b. Umal-Mohammad b. Usmi

ca. 1571-1572

Sorkhey I b. Buday I

ca. 1574-1575 Chub an I

1575-1589

Andi Beg b. Chuban

116

Lavrov 1987, p. 130; Lavrov 1980, p. 108.

117

Keppel 1827, vol. 2, pp. 246, 247; Eichwald 1834, p. 85.

118

Lavrov 1987, p. 130; Lavrov 1980, p. 108; Bérézine 1852, p. 79; Bérézine 2006, p. 66.

119

Lavrov 1987, p. 130; Lavrov 1980, p. 108.

Date Name Tarku branch 1589-1608

Sorkhey II 1608-1619

Geray b. Chuban ?

1619?—1635

Eldar I b. Sorkhey II 1635-1639

Sorkhey III b. Geray 1639-1640

Sorkhey IV b. Eldar Khan b. Sorkhey

1641 Sorkhey V b. 'Ali Beg

1642-1668

Sorkhey VI b. Geray of Tarku

1668 Chuban II

1671 Buday

1672 Mahmud

1682-1688

BudayII

1682-1699 Morteza 'Ali I [?]

1699-1717

Geray Khan

1717-1719 Omalat (Shobhat Shamkhal)

1719-1725

'Adel-Geray b. Buday II

1725-1734

period without Shamkhal 1734-1757/1758

Khass-Bulat b. 'Adel-Geray

1735 Eldar II b. Morteza 'Ali b. Buday II

1744 Ahmad Khan Jangtay

1757-1758 Tishsiz-Bammat (Tishnek Mohammad)

b. Geray of Bammatulin 1757-1758

Mehdi I b. Morteza 'Ali b. Buday II

1758-1785 Morteza 'Ali II b. Mehdi I

1785-1797 Bammat (Mohammad) II b. Mehdi

1797-1830 Mehdi II b. Bammat II

1830-1836

Soleyman Pasha b. Mehdi II

1836-1860 Abu Moslem Khan b. Mehdi II

1860-1867 Shams al-Din b. Abu Moslem Khan

II. Usmi

The Land and People

The Qeytaq or Kheydaq live on the northern slope of the Darband watershed

and on the Caspian seaboard next to Utemish until the border of Shirvan,

i.e. the Darbakh stream. In the West the Qeytaq district borders on that of

the Qara-Qeytaq. It is a fertile land with many villages, of which the main

ones were Bashli and Majales, where the Usmi resided in the eighteenth cen¬

tury. Mostly, the Qeytaq lived in the plains and were engaged in cultivation,

viticulture, horticulture and herding, for it had good pasture land. There¬

fore, in winter people from Aqusheh and Tawlistan would come to herd their

cattle there, for which they paid a certain small fee per head to the Usmi.

However, because there were than 100,000 sheep the total fee was large. The

Qara-Qeytaq or Black Qeytaq lived in the mountains; to the west were the

Qomuq; to the north the Kubesha and to the south Tabasaran. They had

many villages; the main one was Qaragurish. Their land was less fertile and,

therefore, they were poorer than the Qeytaq. Both the Qeytaq and Qara-

Qeytaq engaged in highway and other robbery to supplement their income. 120

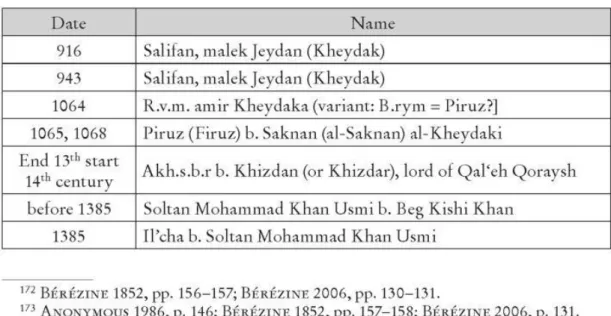

: name Qeytaq or Kheydak already occurs in the ninth century in

Arabic texts. The origin of the name Keydak or Qeytaq is unknown, al¬

though the suggested derivation from the name Qahtan probably is a popu¬

lar etymology to give more credence to the Qeytaq chief after his conversion

to Islam. According to Mas'udi, the only Moslems among the Qeytaq were

their chief, his son and his family. They claimed descent from the Arab gov¬

ernor Qahtan, who had islamicised the area. His title was Salifan, which is

an ancient Turkish title, and Mas'udi calls him Kheydaqan-shah. 121

From the little that is known about the early history of the Qeytaq it is

clear that as in later centuries their political role was strongly linked with

that of Darband. The Qeytaq district provided a place of refuge for the gov¬

ernor of Darband as well as a source for military support against his rivals.

Consequently, the chiefs of the Qeytaq intervened in Darband 's affairs and

at times tried to dominate the city. Another constant was that already in the

tenth century, the country of the Kheydaq had acquired the reputation of

being "the most harmful". 122 The consecutive residences of the Usmis seem

to have been: Qal'eh-ye Qoreysh (Urgmuzda), Ghapsh, and Majales, which

was founded by Usmi Soltan Ahmad, "on an empty place where people used

120 Gärber 1732, pp. 55-56. For more details see Gmelin 2007, pp. 303-306, 308-312.

121 Minorsky 1958, pp. 154, 168 ("the town of Flaydan [read Khaydaq] whose king is called Adhar-narse. Fie adheres to three religions").

122 Minorsky 1958, p. 154.