Hertie School of Governance - Working Papers, No. 39, February 2009

The Decline and Rise of Public Spaces

Papers and Presentations from the International HSoG Conference, October 2008 in cooperation with CivWorld @ Demos (New York) and the support of the US Embassy (Berlin)

About the HSoG Working Paper Series

The Working Paper Series of the Hertie School of Governance is intended to provide visibility, internally as well as externally, to the current academic work of core faculty, other teaching staff, and invited visitors to the School. High‐quality student papers will also be published in the Series, together with a foreword by the respective instructor or supervisor.

Authors are exclusively responsible for the content of their papers and the views expressed therein.

They retain the copyright for their work. Discussion and comments are invited. Working Papers will be made electronically available through the Hertie School of Governance homepage. Contents will be deleted from the homepage when papers are eventually published; once this happens, only name(s) of author(s), title, and place of publication will remain on the list. If the material is being published in a language other than German or English, both the original text and the reference to the publication will be kept on the list.

Table of Contents

4 Conference Programme

The Decline and Rise of Public Spaces

6 Claus Offe

Opening Statement: Arenas of Social Conflict and Political Discourse: Growth or Decline?

21 Harmut Häußermann

Spatial Exclusion and the Policies for Access

39 Donatella della Porta

Social Movements as Public Spaces

52 Bernd Scherer

Counterpoints: The Role of Art in the Public Space

60 Lea Ypi

Public Spaces and the Death of Art: Was Hegel Right?

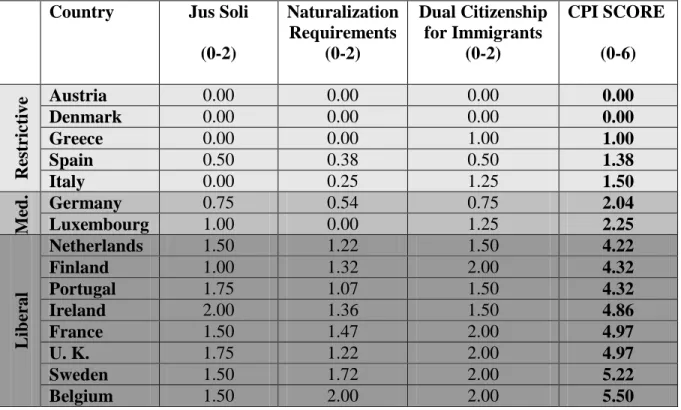

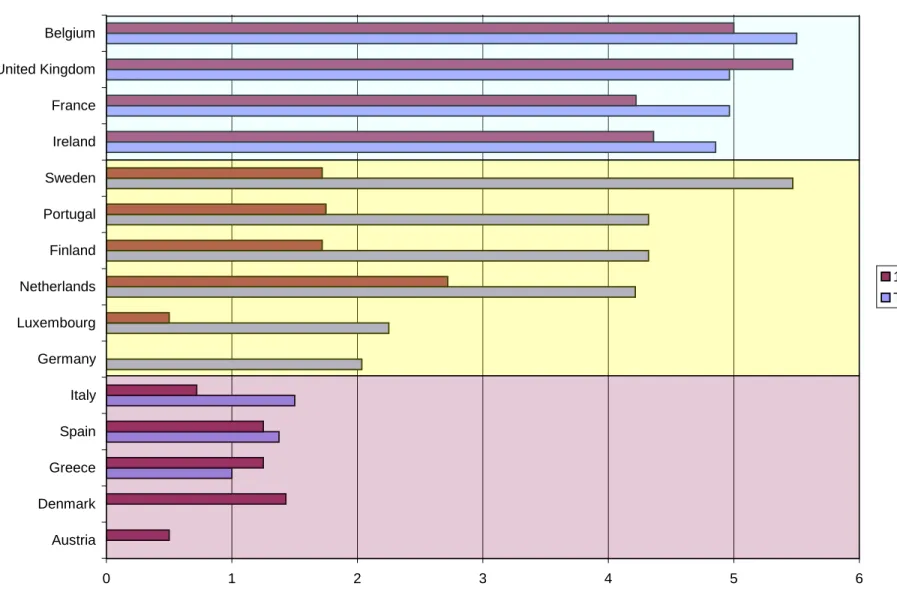

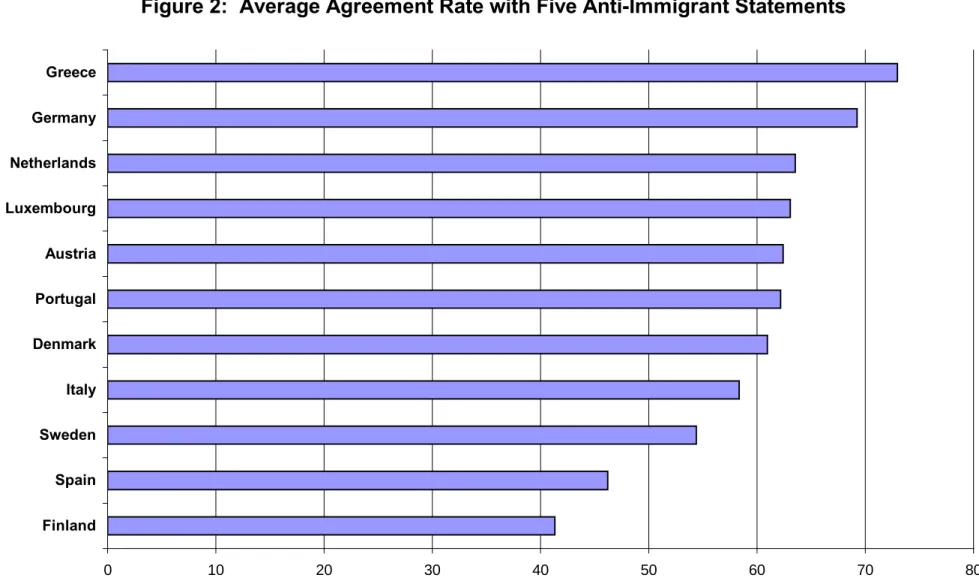

76 Marc Morjé Howard

Varieties of Citizenship in the European Union

106 Christian Joppke

‘Civic Integration’ to Beat the Parallel Society?

125 Antanus Mockus

Policy Innovation and the Culture of Citizenship: Tapping the Moral Resources of a Metropolitan Population

168 Maarten Hajer and Wytske Versteeg The Limits to Deliberative Governance

Saturday, 11 October 2008 Forum A – 1st Floor

9.30 – 11.00 am Panel V: Civil Society and Interactive Governance

Speakers:

Archon Fung Professor of Public Policy, Harvard Kennedy School of Government, USA

Third Generation Transparency and Information Pooling:

Technologies for Democratic Governance

Maarten Hajer Professor of Political Science and Public Policy, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands

The Limits to Deliberative Governance Discussion

Coffee Break – Forum B (1st Floor)

11.30 am – 1.00 pm Panel VI: Conclusions: Public Spaces and the Future of

Governance Speakers:

Benjamin Barber Distinguished Senior Fellow, Demos, USA Ulrich K. Preuss Professor of Law and Politics, Hertie School of Governance, Germany

Michael Zürn Dean and Professor of International Relations, Hertie School of Governance, Germany

Discussion End of Conference

The Conference Theme: ‘Public Spaces’

A public space is an institutional setting where communications take place on matters that concern all members of a community.

These discourses allow for the perception of identities, the understanding of difference and conflict, the probing of legitimacy, and the formation of political will. A public space is defined by its being freely and fearlessly accessible to everyone.

We would like to look at the physical and institutional spaces in which processes such as arguing, bargaining, deliberation, persuasion, and the tapping of ‘moral resource’ are taking place.

Can we point to the emergence of new public spaces (e.g. in the arts and the interactive electronic media)? How do they relate to the decay and deformation of old ones (e.g. the spread of ‘gated communities’ and isolated parallel societies)? To what extent do the associations and organisations of ‘civil society’ provide arenas in which common political problems are defined, be it within or beyond the borders of national societies?

Information:

Axel Rückemann

Communications and Events Hertie School of Governance

Quartier 110 ● Friedrichstraße 180 ● 10117 Berlin www.hertie-school.org

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Tel.: +49 (0)30 – 25 92 19 118 Fax: +49 (0)30 – 25 92 19 444 Email: Rueckemann@hertie-school.org

Conference Programme

The Decline and Rise of Public Spaces

convened by the

Hertie School of Governance, Berlin in collaboration with CivWorld @ Demos, New York

9 – 11 October 2008 Hertie School of Governance Quartier 110 · Friedrichstraße 180

10117 Berlin

The support of the US Embassy is gratefully acknowledged.

Thursday, 9 October 2008 Auditorium – 4th Floor

5.00 – 6.15 pm Opening Panel Welcome:

Michael Zürn Dean and Professor of International Relations, Hertie School of Governance, Germany

Introduction:

Benjamin Barber Distinguished Senior Fellow, Demos, USA Do we live in an age where new public spaces are emerging?

Claus Offe Professor of Political Sociology, Hertie School of Governance, Germany

Arenas of Social Conflict and Political Discourse: Growth or Decline?

Coffee Break (4th Floor)

7.00 – 9.00 pm Keynote Presentations Chair:

Werner Perger Journalist, DIE ZEIT, Germany Keynote Speakers:

Jürgen Kocka, Vice-President, Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften and former President, Social Science Research Centre Berlin (WZB), Germany The Rise and Limits of Civil Society. Some Historical Reflections

Gesine Schwan Former President of the European University Viadrina andcandidate for the federal presidential elections, Germany

Friday, 10 October 2008 Forum A – 1st Floor

9.30 – 11.00 am Panel I: The City and the Politics of Planning and Access Speakers:

Jürgen Bruns-Berentelg CEO, HafenCity GmbH, Germany

Public and Private Spaces: Juxtaposition or New Balance?

Hartmut Häussermann Professor and Chair of Urban and Regional Sociology, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany

Spatial Exclusion and the Policies for Access

Discussion

Coffee Break (Forum B – 1st Floor)

11.30 am – 1.00 pm Panel II: Cyberspace as a Public Sphere

Speakers:

Lance Bennett Director, Center for Communication & Civic Engagement, University of Washington, USA

A Digital Networked Public Sphere?

Donatella Della Porta Professor of Sociology, Department of Political and Social Sciences, European University Institute, Italy Social Movements as Public Spaces

Discussion

Lunch Break (Forum B – 1st Floor)

2.00 – 3.30 pm Panel III: The Public Space of the (Visual) Arts

Speakers:

Lea Ypi Research Fellow, Nuffield College, Oxford University, UK Public Spaces and the Death of Art: Was Hegel Right?

Discussion

Coffee Break (Forum B - 1st Floor)

4.00 – 5.30 pm Panel IV: Migration, Integration, Citizenship Speakers:

Marc Morjé Howard Associate Professor of Comparative Government, Georgetown University, USA

Varieties of Citizenship in the European Union

Christian Joppke Professor of Political Science and Director of the Migration and Integration Research Centre, American University of Paris, France

‘Civic Integration’ to beat the parallel society?

Barbara John Former Commissioner for Migration and Integration of the Berlin Senate and Chairwoman, PARITÄTISCHE Berlin;

Germany

The closing of public spheres for Muslims. Granting cultural liberties as a strategy to improve democratic participation

Discussion

Coffee Break (Forum B – 1st Floor) 6.00 – 8.00 pm Keynote Presentation Chair:

Claus Offe Professor of Political Sociology, Hertie School of Governance, Germany

Keynote Speaker:

Claus Offe October 2008

Opening statement for public space conference

The Hertie School is a school of "public" policy. This key phrase describing our mission invites a reflection on what we actually mean by the qualifier "public".

One obvious answer it that we mean the political community as a whole, or those of its members that are on the receiving side of particular policies - what

sometimes is called the "target population" of public policy, or the universe of

"policy takers". Another answer might be that the public is the place where public policies originate - the setting in which "problems" are recognized and defined, interest, values and preferences shaped, coalitions formed and demands raised.

1The program of our conference is designed to focus on the latter of these two equally legitimate and suggestive perspectives on the "public". Rather than

concentrating exclusively on how representative policy elites accomplish what they want to achieve on behalf of the citizenry they represent (solving problems and improving collective conditions of life), we want to look at the source of problem definitions and preferred solutions as they emerge - and are supposed to emerge

1 The volume in the new Oxford Encyclopaedia that is devoted to the study of public policy carries the title "The Public and its Policies", thus nicely capturing a focus both on the public as the target of policies (the "output"

dimension) and on their motivational and cognitive origin in the "public sphere".

according to democratic principles! - from the "public sphere". To put it somewhat simplistically, we are here interested not primarily in the issue of "how we get what we want", but in the logically prior issue of how political communities and their members "come to want what they want".

I do not have to convince an audience like this that this is by no means a trivial question. Interests and desires are in no way a "natural" outgrowth of social structures. They are rather constructed. True, we are unsurprised if we find that farmers tend to want higher farm subsidies, retired people better pensions, and that all of us presumably prefer peace over war. But there are some well-known

complications. Let me just mention three of them, the phenomena of trade-offs,

conflicts, and ignorance. Trade-off means that the more I get of good or service A

(say, pension increases) the less I can get of B (public health services). Conflict

means that as farmers call for subsidies and protective tariffs, tax-payers and

consumers prefer the opposite. And ignorance refers to the ever more widespread

phenomenon of citizens being genuinely "at sea" on issues such as whether and

how the government should bail out ailing banks. Interests are in no way "given",

and we can well - and do often - err miserably in finding out what they are. It is not

just ordinary citizens, but academic experts as well who sometimes (and not too

rarely) have to admit that they simply do not know, due to their lack of experience

and analysis, what the most desirable course of action actually would be. The prerequisite of "enlightened understanding" that Robert Dahl has postulated as a feature of the practice of citizenship has become an exceedingly demanding ideal.

But that is clearly not all. A second set of complications that bedevils the formation of policy preferences on the part of ordinary citizens concerns the question of whether a problem in question should at all continue to be solved through collectively binding public policy, rather than the issue in question being transferred to private market transactions on the basis of so-called "consumer sovereignty". In the latter case, there is a somewhat paradoxical public policy decision to end parts or all of public policy decision-making in a particular sector of service needs, e. g., a national railway system. There are today powerful

suggestions favoring this latter alternative of privatization and "political outsourcing", driven by both governments trying to rid themselves of the

responsibility and budgetary burdens of collective provisions for collective goods (thus pushing the supply into markets), while at the same time consumers and private suppliers pull the provision of goods and services into markets -- arguing, for example, that the private mode of provision will enhance investment

opportunities, employment, consumers' freedom of choice, and competitive

pricing. These push and the pull forces, taken together, have already led during

recent decades, as we all know, to the partial or full abandonment of former public policy areas, to their de-politicization, and the privatization of the provision of services such as utilities, transportation, telecommunication, health, education, the mass media, and police, prison, security and even some military services.

2As a rule of thumb, it can be demonstrated (and has been widely documented; cf.

Titmuss, Crouch) that a change of the mode of supply affects the quality

characteristics of services. Also, whatever the effects of economic and managerial privatization moves in terms of consumer prices, product quality, and employment prospects in the respective sector may turn out to be, the incidence itself of such effects seems certain. Moreover, these effects extend beyond prices and hence distribution, and also beyond issues of quality. They further pertain to three

additional aspects. First, the changes that result from privatization are more or less irreversible, as the holders of new property rights tend to have very strong legal resources to resist any reversals in case they are proposed and demanded in view of disappointing outcomes. Second, is becomes harder for public authorities to

2 A particularly interesting case is the rise of privatised police forces that do not specialize, like professional police, in the general maintenance of law and order (in German referred to as “SOS”-issues, referring to

“Sicherheit, Ordnung, Sauberkeit”), but focus specifically on the "management of marginality"

("Randgruppen-Management") by dealing with drunkards, drug addicts, street prostitution, etc. (Glasze 2001).

The size of commercial security forces, who in Germany also run deportation prisons for undocumented refugees to be returned to their country of origin, has exploded from less than 50.000 in 1970 to 200.000 in 2005, with sales rising even steeper from 0.3 to 6.0 bn. Euros in the same period. (Eick 2007)

enforce legal as well as social norms (regulatory constraints, professional

standards) applying to the management and operation of privatized facilities; often, the operation of services is handed over to "private government" (i. e., largely unaccountable rule-making and rule-enforcing agencies). A third effect, and the most significant in the present context, is the transformation of citizens and their role in collective decision-making on collectively relevant affairs into private consumers whose predominant concern is with what fits "my" taste best and what it is that "I" can afford, in contrast to what is best for "us" as the collective body of the citizenry. (cf. Robert Reich)

Thus privatization as an economic and managerial category translate into a

category of life style and political culture - mental privatization, as it were, or the

re-framing of public issues into issues of individual choice and consumption. In

this sense "privatization" becomes a detached and self-sufficient mental state that

habituates people to the use of "exit" based on tastes rather than "voice" based on

reasons. Together with evolving markets catering to specialized communities of

life style and income, it can shrink the horizon of citizens-transformed-into-clients

and blind them to the social and temporal externalities of what they practice. Their

capacity for forming judgments on public affairs is in danger of being "under-

challenged", with the consequence, as we know from educational contexts, that

abilities can easily decay in the absence of the challenge to make use of them.

After all, as "I" can afford a sophisticated air conditioning system in my living room which provides me with the pleasant and healthy air temperature, air humidity, and air purity, why should I worry too much about issues of climate change and public policies addressing them? As I can afford to send my kids to a commercial pre-school program that offers advanced pedagogical services and a broad choice of subjects to choose from, why should I worry about issues of

educational reform policies? And as I have become used to buying my groceries in fancy health food stores anyway, I lack any interest in supporting regulatory

approaches concerning food safety. Another example of such "end-of-the-pipe"

philosophy are private nuclear shelters which allow residents to survive a nearby nuclear explosion by up to 40 days; the construction of such shelters has been made mandatory in parts of Switzerland. And, as an admittedly extreme example, as I live in a gated community (as they are increasingly inhabited, complete with private guards, by the well-to-do in Latin America, North America, South Africa, as well as such nearby places as Potsdam's "Arkadia" project), why should I be obliged to continue paying that part of my taxes that go into public police services?

Incidentally, what is valued by users of this form of residential property its quality

as a positional good, its "exclusiveness" -- which is to say, the enforceable absence of unwanted others.

Everywhere we are offered opportunities for market-based "do-it-yourself" policies that compete with and seemingly can substitute for public policies. I believe that these opportunities can account for much of the depoliticization and retreat from public affairs of the middle classes, except, that is, for demands for lowering taxes on wealth and income. This depoliticization amounts to what I would call mental and "cognitive" privatization. By this I mean an aversion to understanding,

learning about, and taking positions on the conditions of other people -- a mental disposition to deny or ignore obligations to or interdependencies between "me" and people who live "far away", be it in spatial or socioeconomic terms. The "secession of the successful" (Robert Reich), in striking parallel to the marginalization of those considered failures, need not just be one in terms of physical space, as differences are being habitually responded to in terms of a generalized attitude of indifference. (Bauman)

Things work differently, although with similar effects, for the escape from political

life of the less prosperous majority of the population. This has to do with a third

and last set of complications that I want to remind you of. In order to become

active in the public sphere at the "input" side of public policy, you need, roughly speaking, three kinds of subjective certainties. First, a reasonable certainty that there is some agency "out there" that will actually "listen" to, be attentive to, and be able to make a difference in response to what you have to say, even in the presence of powerful opponents to the point of view you wish to communicate. In other words, you need a measure of basic confidence in the responsiveness of democratic institutions, such as parties, parliaments, and governments. Second, you need to be reasonably certain that your own concerns and points of view will be shared by others, or that a relevant number of others can be persuaded to adopt and support it. The dissemination of opinion poll results through the media can play a significant role in the very formation of political opinions: As citizens are informed about what "everyone else" thinks, there is a subtle side-effect of

discouraging them to adopt or maintain views that stray too far from what is found to be majority opinion on a particular issue. It is a fact of political life in any mass democracy that strictly individual voices will rarely if ever be heard; they remain

"noise", as letters to the editor of your local paper or the Americans "writing to

their congress man". "Noise" can be transformed into "voice" only if it is heard as

originating from some kind of collective actor - be it a civil society association, a

trade union, a social movement, a local party organization, a faith-based

community, or whatever. Third, however, joining such an organization, or agent of collective voice, is a step that will only be taken by individuals who are

sufficiently confident in the persuasiveness, or "deliberative superiority", of the point of view they wish to raise and who also trust in the willingness and capacity of representative actors of associations to present it fairly and in undistorted ways to the outside world. The transformation of the mere "noise" caused by individual expressions of opinions and preferences into collectively articulated "voice" is, however, not only justified by the instrumental need to make use of an

organizational amplifier; it is equally justified by the consideration that opinions and preferences can be "laundered" (Goodin) and "rationalized" (Habermas) through intra-organizational communicative processes that eventually, in the course of deliberation, lead to the adoption of shared and reasoned positions. At any rate, the presence of these three thresholds results in powerful effects of

discouraged, silenced, and distorted communications. To put it inversely, only after these three thresholds have been passed successfully, communications concerning the design and purpose of public policies will actually make their way into the

"public sphere".

The organizers of this conference are convinced that these thresholds, as well as

the symptoms of privatization and depolitization that I have alluded to before, can

in fact be overcome by strategies to strengthen the public sphere. We have designed the conference to allow for and invite an intellectual search process for modes of strengthening the public and its link to policy elites. A public sphere as an institutional setting is, as I see it, defined by three features. First, it is freely accessible - no fences and no (prohibitive) admission fees (as they limit the access to many cultural events, from concerts to museums). Second, the activities and communications going on are not constrained by one dominant organizational purpose or mission; in this sense, neither a sports stadium nor a hospital nor a department store

3nor a railway station are strictly public spaces, but streets, parks, centrally located urban places are -- modern equivalents of the Greek agorá. Third, public spaces allow for, invite, and encourage both the active display and

perception of difference (of life style, of opinion, of social and cultural background etc.) among those who partake in them. The direct (visual) contact with people differing from "me" seems important and is suggested by the space metaphor when applied to the arts, to the media, or even states and their public spheres. (As one author has put it: "There is no viable social contract in the absence of social

3 In fact, the statutes ("Hausordnungen") of such organizations explicitly prohibit and sanction behaviors that are considered incompatible with the purpose of the organization, such as, in shopping malls, eating, drinking, loitering, playing music, staging artistic or political events, begging, selling items without specific license, collecting donations, conducting surveys, taking pictures for commercial purposes, advertising, sitting on the floor (to say nothing about graffiti spraying or even smoking). (cf. Glasze 2001)

contact.") The perception of difference will, in its turn, give rise to the deliberative dispositions of asking for reasons, giving reasons, and challenging the reasons given by others.

Let me follow up these considerations by addressing the question: What are public spaces good for? Why should it be desirable to search for, defend, develop, and expand spaces - both in the literal and metaphorical sense - to which the

characteristics apply that I have just mentioned? One answer might be that it is intrinsically desirable for people to live and participate in public spaces. Isn't it a positively liberating experience to to move, again both physically and

intellectually, in a space that is not colonized by holders of economic or political power, nor belongs to someone's private sphere? Furthermore, such spaces might be considered intrinsically valuable as they provide the mental training ground for the competencies and virtues of citizenship -- opportunities for overcoming

resentment and prejudice, understanding difference, learning about others, and for

validating in the process our own views, concerns, and opinions. Although I

believe that all of these intrinsically valuable features of public spaces can be

postulated with good reasons, I want to focus instead on the instrumental or

functional role that public spaces can play in strengthening a democratic polity.

What is a "strong" democracy? Although there are clearly many answers to that question, I think that most of them converge on desirable features of political communication. Much of contemporary democratic theory deals with the re- constitution of the public sphere though designing and re-designing flows and modes of communication about public affairs. Governing elites must be able, and if need be even forced, to "listen" (both to non-elites and to elites outside of government). They also must be able, and if need be even forced, to "speak" in terms that enhance and broaden the understanding on the part of non-elites for the nature of collectively relevant affairs and proposed solutions. In fact, the ability to persuade non-elites through communication has become a major tool not just of winning mandates and positions of political power, but especially of implementing policies in a process that some of our Dutch colleagues have termed "interactive policy making" through the use of "social mechanisms". And non-elites must be able to communicate among themselves, thus arriving at well-considered and deliberatively "laundered" views and demands, however conflicting, and communicate the results effectively to governing as well as other elites.

Dozens of proposals for new "communication designs" (Habermas) or a "general

restructuring of democratic decions making" (Fung and Wright 2001: 8) have been

launched and experimented with by political scientists, activists, and philosophers

in recent years. "Participatory budgeting", "deliberation day" proceedings, the use of "mini-publics", demands for "targeted transparency", the systematic

involvement of "lay stakeholders" and various strategies for devolution and

decentralization aiming at "empowering local units" are just a few items on a long list of similar proposals (of which Graham Smith (2005) has identified and

described no less than 57). Most of them are inspired by recent research and theorizing on civil society, social capital, and the "third sector"; conversely, the practical work on and design of new patterns of democratic decision-making has given rise to complex and fancy theoretical innovations such as "constructivist"

(Hay) or "discursive" (Schmidt) institutionalism. Many of the best minds in policy analysis as well as practical policy-making are involved in the emerging field of what might be called "meta" policy-making - the designing, testing, implementing and critical assessment of institutional patterns in which the communicative

process of ordinary policy-making is - or for normative reasons spelled out by democratic political theory, ought to be - embedded.

The critical insight that has triggered this wave of proposals for democratic innovation is the view that the official main roads of the vertical communication between elites and non-elites, namely campaigning, voting, and media

consumption, are vastly inadequate mechanisms in terms of assuring a minimum of

democratic accountability as well as reasonably intelligent policy outcomes.

Political communication through mass media, as we know, is unilateral: readers and viewers can't talk back. Where they actually can, as in interactive electronic media, the prevailing practice is that you talk to the likes of yourself, to whom you feel no reason to talk back. In both cases, the ever-present option of tuning out, of

"exit", is not exactly conducive to the formation of "voice".

In conclusion, I wish to highlight three features of current and often highly

"practical" proposals to restore, develop and strengthen institutional frameworks of the public sphere. First, this field of "meta" policy making - or of restructuring the communicative patterns in which "normal" policy making is being embedded - does not operate at the level of classical meta-policy, which consits in the writing, rewriting, and critique of political constitutions. What we find instead in current debates on meta-policy making is the "sub-constitutional" pragmatic advocacy of and experimentation with new communicative practices which make use of both the availability of new communication technologies and the rise of new issues and corresponding patterns of social and political mobilization. Second, and in contrast to earlier demands for political reform that started with claims about the "given",

"true", or even "objective" interest of some constituency which had to be mobilized

and united in the pursuit of these common objectives or values, the new generation

15

of political innovations that I have referred to put a much heavier emphasis on cognitive and epistemic rather than motivational and value-related aspects of the political process. At the core of these reform initiatives is the idea that deceptive frames need to be replaced by more complex and adequate ones, and that

enlightened understanding of interdependence and the competent interpretation of issues is the key variable and precondition for finding out about shared interests and values. What is being called for is "transparency", or the political equivalent of competent and reliable "rating agencies", capable of public disclosure of what otherwise would remain in the realm of clandestine practices of rulers and their

"dirty secrets". Thirdly, and fully in line with the cognitive emphasis and the sub- constitutional mode of operation, there is a strong preparedness in these reform movements to have the deliberative stage of the policy process (in which we find out about issues, interests, and possible coalitions) separated from actual political decision making, whereas the fusion of the two is part of the essence of

conventional politics of party competition: We, the leadership of party X tell you

what is good for all of us and through which of our policy decisions we are going

to get there. However, it is only within the context of a solid public sphere that the

two sides of policy - analysis and deliberation vs. decision and implementation -

can encounter each other and enter into productive friction.

Spatial Exclusion

and the Politics for Access

Hartmut Häussermann

Humboldt‐Universität zu Berlin

Cities as public spaces

• ‘European City’: Cities are collective actors.

• Public space is shared space – physically and socially.

• Relational category.

• Cities are public spaces

10 October, 2008 Conference on Public Space, Hertie‐School22 2

Segregation and Exclusion

• Urban Space is structured space

• Segregation, voluntary and involuntary

• Social distances – spatial distances

• Spaces of exclusion

Socio‐economic Changes and Segregation

Tendencies in big cities:

• Growing inequality of incomes

• Growing ethnic heterogeinity

• Lower social transfers

• Deregulation and privatization of the

housing sector: declining shares of ‚social‘

housing

• Growing concentration of ethnic minorities in certain neighbourhoods: residualisation

10 October, 2008 Conference on Public Space, Hertie‐School24 4

Ghettos?

• Still multicultural neighbourhoods

• No ‚Ghettos‘

• But an overlay of high shares of poor households and migrants with a low education‐status

• ‚Underclass of the migrant population‘ ist

segregated and spatially concentrated

10 October, 2008 Conference on Public Space, Hertie‐School

Statistical units with highest shares of Turks,

in which in 2006 in sum 30% of all Turks in Berlin live.

26 6

Shares of young foreigners in the age of below 18 of all below 18 years

Shares of unemployed 2006

10 October, 2008 Conference on Public Space, Hertie‐School28 8

Coexistence

Urbanity:

• coexsitence of heterogeneous ethnic/cultural groups in spatial proximity.

• Base: Anonymity, mutual disinterest, inner distance

• Low level of social interaction on the base of spatial proximity.

• Urban way of life.

Coexistence?

• In Schools: no evasion possible (catchment areas)

• Higher segregation of migrant

students in schools than of migrants in the neighbourhood

• High concentration of students with a non‐German mother‐language in certain schools

10 October, 2008 Conference on Public Space, Hertie‐School30 10

Parallelwelten ‐ Migrantenviertel und deren Bedeutung Shares of students with a

non‐German mother‐

language

Status‐Panic

Middle‐class strategies:

• Protection against some sort of ‚infection‘

• Protection of status and privileges

10 October, 2008 Conference on Public Space, Hertie‐School32 12

Coexistence?

• Social distance spatial distance

• Exit from public space, not voice

• discharging shared (public) space

• Crash‐down of the public space

results in lower levels of education

• Exclusion of the left‐behinds:

underclass of tomorrow

Public space?

Exclusion as a consequence of the education strategies of the

middle‐classes.

The end of education as a public project in a joint public space?

10 October, 2008 Conference on Public Space, Hertie‐School34 14

Policy‐options: 4 examples

Area‐based strategies:

France: forced mixité

Netherlands: forced heterogeinity Germany: Improvement on site

USA: changing the context

Public space?

Spatial solutions for social problems?

Shared physical space

= shared social space?

10 October, 2008 Conference on Public Space, Hertie‐School36 16

Public space?

Reconstruction of public space on a non‐spatial level?

Sense of belonging?

‚Local solidarity‘?

Public spirit is a necessary condition

‐ for access

‐ for a just / fair city

10 October, 2008 Conference on Public Space, Hertie‐School 18

The end.

Thank you for your attention!

38

Social Movements as Public Spaces

Donatella della Porta

European University Institute

Declaration of the European social movements, 1 ESF, 2002

¾ We have come together to strengthen and

enlarge our alliances because the construction of another Europe and another world is now

urgent. We seek to create a world of equality, social rights and respect for diversity, … We have come together to discuss alternatives…

Great movements and struggles have begun

across Europe: the European social movements

are representing a new and concrete possibility

to build up another Europe for another world”

Definitions of the Social Forums as

¾ “open meeting place” (WSF)

¾ ‘ideas fair’ for exchanging information, ideas and experiences horizontally” (activist)

¾ “an exchange on concrete experiences” (“La Stampa, 10/11/2003),

¾ “an agora” (“Liberazione”, 14/11/2003),

¾ a kermesse (“Europa” 3/11/2003),

¾ a “tour-de-force of debates, seminars and demonstrations by the new global” (“L’Espresso” 13/11/2003),

¾ “a sort of university, where you learn, discuss and exchange ideas”

(“La Repubblica” 17/10/2004),

¾ “a supranational public space, a real popular university” (in

“Liberazione” 12/10/2004).

More in general

¾ Social forums belong to emerging forms of action that stress, by their very nature, some values that are central for the conceptions of a public spaces, such as

openness toward the “other”, plurality and inclusion.

¾ Reflecting a continuous search for spaces where communication between groups with very different organizational forms, issue focus and national

background can develop, free from the immediate concerns for decision of strategies and actions.

¾ So: for the construction of public spaces where

“communication take place on matters that concern all

members of a community collectively”.

Main elements of open spaces stressed by movement organizations:

¾ Participation: inclusion, equality, horizontality…

¾ Deliberation: search for the public good, dialogue, preference transformation,

diversity…

¾ In free spaces

In the paper:

¾ in the social movement organizations involved in the global justice movement the attention to the creation of public spaces is framed within some old but also some emerging values, among which the that of consensus building acquires most relevance (§ 2).

¾ Consensus is coupled with the vision of the movement as an open space in which diverse and heterogeneous actors meet and debate.

However, in a very heterogeneous movement, the very conception of consensus varies, and with it the conception of a public space, with more communitarian vision stressing common identity and more

“networked” conceptions, stressing diversity (§ 3).

¾ For all the analysed groups, however, the self definition as public spaces is influences by the availability of new technology for

networking, whose use by the global justice movement is going to

be assessed (§ 4).

Table 1. Internal and general democratic values (%; No. of cases 244)

Internal Values % of yes External Values % of yes

Consensual method explicitly mentioned

17.2 Deliberative democracy explicitly

mentioned

7.0 Difference/plurality/heteroge neity mentioned

47.1 Participatory democracy explicitly

mentioned

27.9 Participation 51.2

Inclusiveness explicitly mentioned 20.9 Inclusiveness 25.8

Explicit critique of

delegation/representation

11.1 Dialogue/communication 31.6 Non-hierarchical decision-making

explicitly mentioned

16.0 Equality 34.0

Limitation of delegation explicitly mentioned

6.6 Transparency 23.8

Rotation principle explicitly mentioned

6.6 Autonomy (group; cultural) 18.9

Mandate delegation explicitly 6.1 Individual liberty/autonomy 21.7

Self conception as open spaces

¾ Derechos para Tod@s defines its role as “to contribute to the

spreading of debates, not by narrowing spaces, but by opening them to all those who are critical of this globalization that causes

exploitation, repression and/or exclusion … No alternative to the current system can be regarded as the ‘true’ one. That is, we want to set up a space to reflect and to fight for a social and civil

transformation”

¾ Attac is “’a place, where political processes of learning and

experiences are made possible; in which the various streams of progressive politics discuss with each other, in order to find a common capacity of action together”

¾ Foro Social de Palencia is a “permanent space for encounters,

debates and support for collective action”, where “decisions are

made by consensus”.

Use of the internet by GJM’s activists (%)

Frequency

Internet use Online

petitio ns / campa

igns

Net- strikes

and / or other radical

online actions

Exchan ge of informa

tion with own group

Politic al opinio

ns online

At least once a week 14.9 3.8 48.7 21.2 At least once a

month

26.0 6.6 16.2 21.9

Less frequently 44.3 20.2 15.1 32.7

Demos WP5, in della Porta and Mosca forthcoming

Evaluation of the role of the internet (%)

Internet’s impact

Target Public

administr ators

Mass Media

Members and symphati

zers

Negative 52.9 21.6 3.3

Both negative and

positive 3.2 7.0 15.4

Positive 43.9 71.3 81.3

Total (N)

100.0 (157)

100.0 (171)

100.0 (182)

Cramer’s V is: n.s. (public administrators); n.s. (media); 0.246** (members).

Demos WP4, in della Porta and Mosca forthcoming

INDEXES of

online democracy

ENVIRONMENTAL CHARACTERISTICS

Internet access

Constellatio n of the

GJM Information provision 0.154** 0.187**

Identity building n.s. 0.181**

Transparency -0.188** -0.235**

Offline Mobilization 0.105* 0.173**

Online Mobilization n.s. n.s.

Intervention on digital divide

n.s. n.s.

Total (N) 231 231

External and internal characteristics’ influence on web sites’ qualities (Kendall’s Tau-B)

INDEXES of online democracy

ORGANIZATIONAL CHARACTERISTICS

Horizontalit y (lack of

roles)

Formalizatio n (fee membership)

Local level group

Budge t

Age of the group

Delegation of power (0=executiv

e)

Decision- making method (0=majority)

Information provision -0.242** -0.160** n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Identity building -0.125* -0.105* -0.126* n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Transparency 0.409** -0.257** -0.206** 0.444

**

-

0.287**

-0.288** -0.207**

Offline Mobilization n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s. 0.141* n.s. n.s.

Online Mobilization -0.160** -0.287** -0.118* n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Intervention on digital divide

n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s. 0.264** n.s.

Total (N) 261 261 261 139 150 158 160

Legend: ** = significant at 0.01 level (2-tailed); * = significant at 0.05 level (2-tailed

Social movement areas’ influence on web sites’ qualities (Kendall’s Tau-B)

INDEXES of online democracy

Social movement areas

Old left New left New global

New Social Movements

Solidarity / Peace / HR

Information provision n.s. n.s. -0.142* n.s. n.s.

Identity building n.s. n.s. n.s. 0.138* n.s.

Transparency 0.140** n.s. -

0.331**

0.112* 0.160**

Mobilization n.s. -0.122* 0.107* 0.108* n.s.

Intervention on digital divide

n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s. -0.146*

Total (N) 257 257 257 257 257

Legend: ** = significant at 0.01 level (2-tailed); * = significant at 0.05 level (2-tailed); n.s. = not significant.

Bernd Scherer

Counter-Images. A Contribution to Art in Public Space

On February 2, 2003, I watched the news on TV in our house in

Coyoacán, a southern district of Mexico City. After the news, the traffic helicopter of the TV broadcaster Televisa appeared, hovering over one of the city’s arterial roads, the Reforma. The commentator drew the pilot’s attention to a traffic island in a roundabout with a palm tree at the centre. Confused, he asked the pilot what had happened there. The beautiful gardens previously characterizing this “circle” had disappeared weeks ago and made way for a sandy desert. He added the remark that the city appeared to be incapable of coping with this problem. Without knowing it, the commentator reported on our art project “Agua – Water”.

Why an art project on the theme of “water” in Mexico City?

Anyone dealing with Mexico City will soon discover that the issue of water is one of the most important problems, if not the most important one in Mexico. A third of the municipal budget is spent on public water supply. The city consumes three billion cubic meters of water each year, and the ground-water table is continuously sinking. Water must therefore be pumped from the surrounding areas, resulting in fields becoming too salty and farmers moving to the city, where even more water is then needed.

The water problem affects a metropolis that was once a lakeside city with numerous canals. The history of Mexico can indeed be written as a

history of water.

Prior to the arrival of the Spaniards, the Central American indigenous population had developed its own water culture, including, among other things, floating gardens on lakes. In the religion of the Aztecs, Tlaloc, the god of both water and fertility, played a central role around which social life was organized.

After the Spaniards had conquered the pre-Columbian city of

Tenochtitlán, they began draining the city, many canals were filled in. It is interesting that the urbanization of Mexico was pressed ahead by the Castilians, while the Andalusian immigrants developed the rural

hacienda culture. Owing to its Arabian heritage in southern Spain, this culture is unfamiliar with a close connection between water and

architecture. Mexico’s history of water thus reflects European cultural history. The Spaniards went ahead with this development at such a rapid pace that, at the end of the 18th century, the German scholar Alexander von Humboldt, on his journey through Latin America, appallingly

asserted:

“The Spaniards have treated water as an enemy. Apparently, they wanted this New Spain to be just as dry as the inner regions of their old Spain.” In this context, Humboldt coined the term “Castilisation” of the Valley of Mexico.

Water was buried once and for all in the 20th century. The nationalization of the oil industry in the 1930s led to a booming automobile industry.

Road construction and the subsequent levelling of the last canals

became a sign of the victorious modernization of the city.

Today, the element of water is all but erased from the face of the city.

Yet we encounter traces of it everywhere; it is virtually inscribed in the cityscape. Be it that entire street systems are named after courses of rivers, or that building façades have sunken more than a meter below street level, to mention just two examples.

These observations led to the art project “Agua – Water”. The artists intervened in central locations of the city related to water with

installations and actions. In the process, they created a cartography of the metropolis, confronting it with its own history, as well as with its present-day problems. It is not by chance that the project resulted in a critical examination of Mexico’s path to modernity.

1. The Aquarium

The central symbol of this modernity, the incarnation of the belief in progress, can be found at the entrance to the old city centre, the Torre Latinoamericana. Measuring 171 meters in height, it was long the city’s highest structure. Thanks to a hydraulic tub, which counts as a

masterwork of engineering, it withstood even the most severe earthquakes.

On clear days, of which there aren’t many due to the air pollution, the visitor who makes it to the top of the tower has an overview of the city.

Beneath the viewing platform he then comes upon an installation making

up for the vista of a grey concrete jungle. A colourful water world unfolds

there in a private aquarium set up high above the city by a businessman

to show how he would like to see the world. The visitor can take part in it

by paying an admission fee.

This is where the artist Miguel Calderón intervened with a counter-image.

He brought into the artificial world of the aquarium fish from the polluted lake in Chapultepec Park, the city’s largest recreation centre, in which nobody wants to bathe anymore. Calderón replaced the signs describing exotic fish species with the names of the fish from the lake, imparting information on their living conditions, the water’s degree of pollution etc.

With this action, Calderón inserted the reality of public space into the separated, artificial world of a private space. The owner of the aquarium created his own world with a nature that itself is merely fictitious. For here, too, nature had long become nothing more than a representation of an idyll.

Miguel Calderón thus questioned both the reality created by modernity and its forms of representation in private spaces by again placing them in the realm of public debate. Figuratively speaking, he turned the space with the aquarium at the top from its head to its feet.

2. The Sky Over the City

In Mexico City, as in many other cities around the world, private capital not only determines development on the ground, but also in the sky.

Looking up when driving by car, Mexicans see pictures that tell them

what modern life is all about. Between earth and sky, huge advertising

billboards present the world of commodities that decisively shapes the

lives of Mexicans. Among these images are products that substantially

contribute to water pollution. The world of images in the sky prevents

people from looking to the ground. Christian Jankowski chose these

billboards as the medium of his project.

He conducted interviews with water experts, but he was less interested in their expertise than in their everyday understanding and treatment of water. One of his other major concerns was to reconnect knowledge that has become isolated during the course of modernity to the practice of everyday life. This is derived from the fundamental experience of modernity that specialized knowledge has become so detached from contexts of action that it has lost its relevance to action for those directly affected and is thus no longer available in public space.

Jankowski is interested in the interrelation of science and life. What are the motives that drive scientists on? Statements such as “Aesthetics can be a help” were made in these interviews. Jankowski condensed them to slogans and passed them on to designers, who in a dialogue with the artist then developed the picture language of the billboards. These sentences effected a break with advertising aesthetics that exploits the world of imagination associated with water. Language interrupted the consuming absorption of the visual world of commodities. Direct individual consumption was thus opened for a public discourse.

The Garden Of Paradise

Although the privatization of property has increased in Mexico City in

recent years, urban space is to a large extent still characterized by this

state’s understanding of nation and modernity, whose myth of origin

goes back to a revolution. It is therefore not by accident that many street

names are reminders of the history of the revolution, e.g., the Reforma,

one of Mexico’s magnificent boulevards. And this leads me back to the

helicopter experience mentioned earlier.

People driving along the Reforma encounter on the median strip a

number of monuments commemorating Mexico’s glorious past. Only one place sticks out, in the centre of which the mentioned palm tree stands, decorated with beds of flowers blooming all year round. This is where the city created a picture of flourishing nature alongside the images of

becoming a nation. In the municipality’s project of adapting modernity, characterized by broad streets, nature is attributed its place as a project of representation. It is frozen to an image. The artist Betsabeée Romero destroyed the illusion, the deceptive character of this image. Ten large lorries delivered sand. The image of a paradise was turned into a desert – corresponding to the surrounding desert made of concrete. The

manipulative character of this allegedly natural symbol was replaced by an even stronger image. The government’s privilege of interpretation was undermined and opened to a public discourse.

The World Wide Web

Arcangel Constantini’s project visualized the detachment of knowledge from concrete experience inherent to the project of modernity. He

confronted the inhabitants of the Valley of Mexico, the “Chilangos”, with their natural history, which is part of their cultural history. He placed the Valley’s oldest still living species, the Axolotl, a salamander variety that lives both in water and on land, in an aquarium which he exhibited in one of the city’s busiest metro stations. Here, the victors in the Chilangos’

struggle for survival were able to look through a window and observe their counterpart threatened by extinction.

The artificiality of the situation – we only experience nature indirectly –

was demonstrated in another window, in which one saw one’s own

Internet. The examination of the natural environment turned into a virtual observer situation that confronted the audience stepping out of the

metro. The anonymous place through which masses of people flow became a site of examination and discussion. The virtual space of the World Wide Web was connected to this real space. The WWW

constantly provided information on the Axolotl’s situation, while simultaneously showing those observing it.

I would like to conclude with two remarks:

1. The history of Mexico City is also a history of colonizing water. The reappropriation of water in new, provocative images therefore

contributed to its decolonialization. Two processes ran in parallel. The new images again called to mind what was buried, what had

disappeared. Hence, they reinstated water as an issue of public debate.

At the same time, the projects engendered a public sphere in a variety of ways. On the one hand, in the process of developing the project.

Jankowski’s billboard project showed that different groups of society were involved, ranging from scientists and bureaucrats to designers and agencies – more than 600 persons over a period of two years – and on the other, the installation of the artworks themselves that prompted the most various debates.

2. Mexico possesses a long history of art in public space. The muralists are internationally the best-known examples. For quite a while, these pictures defined the history of the Mexican nation-state – the most

striking example being Diego Rivera’s murals on the Presidential Palace.

They were commissioned by the government that saw itself legitimized

as the ruler of the people by the history of the revolution. The artists

grasped themselves as part of this national project, which was naturally

only aware of a linear history. As a consequence, these works were understood as being timeless, they substantially contribute to defining the cityscape.

Our project, in contrast, only lasted two and a half months. It was based

on the insight that not only one, but many stories can be told in the city,

that there is not only one public sphere in the modern city, but many.

Lea Ypi

Nuffield College, Oxford

Public Spaces and the End of Art*

The peculiar nature of artistic production and of works of art no longer fills our highest need. […]

Those who delight in lamenting and blaming may regard this phenomenon as a corruption and ascribe it to the predominance of passions and selfish interests which scare away the seriousness of art as well as its cheerfulness; or they may accuse the distress of the present time, the complicated state of civil and political life which does not permit a heart entangled in petty interests to free itself to the higher ends of art.

[…] However all this may be, it is certainly the case that art no longer affords that satisfaction of spiritual needs which earlier ages and nations sought in it, and found in it alone […] In all these respects art, considered in its highest vocation, is and remains for us a thing of the past”.

G.W.F. Hegel, Aesthetics, Lectures on Fine Art, pp. 9-10.

I. Introduction

Democratic theory has recently experienced a welcome shift from a purely normative interest in the discursive conditions necessary to an appropriate exercise of political judgement to a more empirically informed study of the public spaces in which the latter is thought to take shape.1 At the heart of this theoretical enterprise lies a healthy scepticism about the idea that discursive rationality may, alone, be sufficiently solid to nurture citizens critically informed assessment of their political institutions and facilitate their engagement in open, democratic deliberation. Public spaces, whether physical or virtual, institutional or cultural, have come to represent an appropriate object of enquiry,

* I first presented the ideas that inspired this paper at a conference on the “Decline and Rise of Public Spaces”

held in Berlin at the Hertie School of Governance. I am grateful to numerous participants at the conference for their questions and encouragement, to John Parkinson and Julian Stallabrass for useful bibliographical suggestions and to Renato Caputo, Claus Offe and Jonathan White for many inspiring discussions on the topic.

The paper is still a rough draft, please do not cite without permission.

1 See for a recent discussion and review of the literature Goodin 2008.