Hertie School of Governance - Working Papers, No. 41, June 2009

The Nordic Model: Conditions, Origins, Outcomes, Lessons

Matti Alestalo (University of Tampere)

Sven E.O. Hort (Södertörn University College, Stockholm) Stein Kuhnle (Hertie School of Governance and University of Bergen)

About the HSoG Working Paper Series

The Working Paper Series of the Hertie School of Governance is intended to provide visibility, internally as well as externally, to the current academic work of core faculty, other teaching staff, and invited visitors to the School. High‐quality student papers will also be published in the Series, together with a foreword by the respective instructor or supervisor.

Authors are exclusively responsible for the content of their papers and the views expressed therein.

They retain the copyright for their work. Discussion and comments are invited. Working Papers will be made electronically available through the Hertie School of Governance homepage. Contents will be deleted from the homepage when papers are eventually published; once this happens, only name(s) of author(s), title, and place of publication will remain on the list. If the material is being published in a language other than German or English, both the original text and the reference to the publication will be kept on the list.

The Nordic Model: Conditions, Origins, Outcomes, Lessons

1Matti Alestalo, University of Tampere

Sven E. O. Hort, Södertörn University College, Stockholm

and Stein Kuhnle, Hertie School of Governance and University of Bergen

“It is widely thought that the Nordic countries have found some magic way of combining high taxes and lavish welfare systems with fast growth and low unemployment…Yet, the belief in a special Nordic model, or “third way”, will crumble further in 2007.”

The Economist, The World in 2007, Edition, 2006, 44

1. MAJOR CHARACTERISTICS OF THE NORDIC MODEL2

Since the 1980s, based on results from a number of comparative studies of welfare states the concept of a ‘Nordic or Scandinavian model’ or ‘welfare regime type’ has successfully entered our vocabulary, whether that of international organizations, that of scholars and that of mass media covering the Nordic countries. For the most part the concept has a positive connotation, but not always, this being dependent upon context and the eyes of the observer. Neo-liberals and old Marxists seem to share a skeptical view, while social democrats more gladly than most bring out a

1This paper will be published in Chinese translation in a book edited by Stein Kuhnle, Klaus Petersen, Pauli Kettunen, and Chen Yinzhang on The Nordic Welfare States – A Basic Reader (forthcoming, Fudan University Press, Shanghai, 2010).

2We thank Jenni Nurmenniemi for her assistance preparing the figures and tables. A draft version was first presented at the Berlin symposium in honour of Peter Flora on the occasion of his 65th birthday (Berlin, March 6-7, 2009). We would like to thank Valeria Fargion, Peter Flora, and other participants who made valuable comments and suggestions regarding contents and form. The authors are solely responsible for the views presented and any remaining errors.

strongly positive view. In fact, many Nordic social democrats will claim that it is their model, but in a historical perspective that is much too simplistic. Within the Nordic countries the notion is

generally positively laden to the extent that political parties have competed for the ‘ownership’ of the kind of political system and welfare state that the concept is seen to denote. The concept is broad, vague and ambiguous, but it is a helpful reference for observers of varieties of market- oriented welfare democracies (cf. Leibfried & Mau 2008). But we can also observe that European welfare states seem to be on a track of mutual learning, in particular in the areas of family and labour market policies (Borrås & Jacobsson 2004). European welfare state models are becoming more intermixed (Cox 2004; cf also Abrahamson 2002). However, there are also some academic

‘dissidents’ (Ringen 1991) who would say that there is no such thing as a ‘Nordic’ model, and that political systems or welfare states simply do not come in types.

We use the concepts of ‘Scandinavian’ and ‘Nordic welfare states,’ or ‘Scandinavian’ and ‘Nordic welfare model’ interchangeably. Both concepts are used in the literature. In geographic terms, the Scandinavian proper would be the mountainous peninsula of Norway and Sweden while ‘Nordic’

includes Denmark, Finland, and Iceland as well. For historical, institutional, cultural, and political reasons (Nordic regional political, institutionalized cooperation since 1950s, e.g., creation of a passport union, a free Nordic labour market and a ‘social union’) we use the concepts

‘Scandinavian’ and ‘Nordic’ interchangeably (cf. also Hilson 2008). In terms of ‘welfare states’ or

‘welfare models’ the five countries, with some exceptions for Iceland, also share a number of characteristics as will be accounted for in the text. If we accept the notion of a Nordic welfare model, the analytical findings of a very comprehensive literature can be summarized in three master statements:

Stateness. The Nordic welfare model is based on an extensive prevalence of the state in the welfare arrangements. The stateness of the Scandinavian countries has long historical roots and the

relationship between the state and the people can be considered as a close and positive one. The implication is not that the state sends “… rain and sunshine from above” (Marx (1852) 1979: 187- 188) but rather that the 20th century state has not been a coercive apparatus of oppression in the hands of the ruling classes. It rather has developed as a peaceful battleground of different classes assuming an important function “as an agency through which society can be reformed” (Korpi 1978: 48). The stateness implies weaker influence of intermediary structures (church, voluntary organizations, etc.) but it includes “relatively strong elements of social citizenship and relatively

of the Scandinavian type of welfare state (Flora 1986: xvii-xx). The role of the state is seen in extensive public services and public employment and in many taxation-based cash benefit schemes.

It should be remembered, however, that social services are mostly organized at the local level by numerous small municipalities that makes the interaction between the decision makers and the people rather intimate and intensive. “The difference between public and private, so crucial in many debates in the Anglo-American countries, was of minor importance in the Scandinavian countries.

For example, until recently it has been considered legitimate for the state to collect and publish records of individual citizens. It is probably no accident that Sweden and Finland have the oldest population statistics in the world.” (Allardt 1986: 111).

Universalism. In the Nordic countries the principle of universal social rights is extended to the whole population. Services and cash benefits are not targeted towards the have-nots but also cover the middle classes. In short: “All benefit: all are dependent; and all will presumably feel obliged to pay” (Esping-Andersen 1990: 27-28). The universalistic character of the Scandinavian welfare state has been traced to “both idealistic and pragmatic ideas promoted and partly implemented” in the making of the early social legislation in the years before and after the turn of the twentieth century.

For the first, social security programmes were initiated at the time of the political and economic modernization of the Scandinavian countries and “the idea of universalism was at least a latent element of the “nation-building” project.” Secondly, the similar life chances of poor farmers and poor workers contributed to the recognition of similar risks and social rights: “Every citizen is potentially exposed to certain risks.” Thirdly, especially after the World War II there has been s strong tendency to avoid the exclusion of people with poor means in Scandinavia. And finally, there has been a very pragmatic tendency to minimize the administrative costs by favouring universal schemes instead of extensive means-testing (Kildal and Kuhnle 2005; Kuhnle and Hort 2004: 9-12).

Equality. The historical inheritance of the Nordic countries is that of fairly small class, income, and gender differences. The Scandinavian route towards the modern class structure was paved with the strong position of the peasantry, the weakening position of the landlords, and with the peaceful and rather easy access of the working class to the parliamentary system and to labour market

negotiations. This inheritance is seen in small income differences and in the non-existence of poverty (Ringen and Uusitalo 1992: 69-91; Fritzell & Lundberg 2005: 164-185). Moreover, Scandinavia is famous for her small gender differences. When the municipalities share a great part of the responsibilities for childcare and care of the old and disabled and when the employment rates of women are high, the gender differences play a lesser role in the Nordic countries than in other

parts of the advanced world (cf Sainsbury 1999; Lewis 1992). Keeping in mind the relatively high welfare benefits, the extensive public services, and women’s good position in the labour market it has been, somewhat ironically, pointed out that Scandinavian men are “emancipated from the tyranny of labour market and Scandinavian women are emancipated from the tyranny of the family”

(Alestalo and Flora 1994: 54-55).

The argument about the existence of a special type of a welfare state in the Nordic countries

presupposes an analysis of its historical conditions. This is done in section two below. Our aim is to show, from a comparative perspective, how the Nordic welfare state emerged and became

especially flourishing in the four decades following World War II (section three; for more detailed analyses, see also the individual country histories in this volume). After that, during the 1990s and the 2000s there have been extensive changes in the basic conditions of welfare arrangements almost throughout the advanced world. In the sections four and five we try to analyze how the Nordic countries have succeeded to maintain their welfare states in the high waves of globalization and European integration and faced with the challenges of changing class structures and ideological discourses. Finally, we shortly discuss the lessons and prospects of our story and situate the

contemporary “Nordic Model” within the boundaries of the geography of comparative welfare state research and the current possibility of “de-globalization”.

2. CONDITIONS OF MAKING THE NORDIC MODEL

The Scandinavian Route

Three factors are of major importance in characterizing the Scandinavian route of a peaceful process of general change from semi-feudal agrarian societies to affluent welfare state societies.

The Scandinavian route was not paved by bourgeois revolution as in Britain and France, or by conservative reaction culminating in fascism as in Germany, or by peasant revolution leading to communism as in Russia (Moore 1966). These three transformations are:

(1) The increasingly strong position of the peasantry during the preindustrial period which was connected with

(2) The weakening position of the landlords and the power-holding aristocracy as a result of

(3) Became a peripheral area in economic and political terms (Alestalo 1986, 11-12; Alestalo and Kuhnle 1987).

A unique feature in the Scandinavian class formation was the rise of the class of independent peasants as a result of the individualization of agriculture (increased peasant proprietorship, enclosure movements (see Osterud 1978: 113-151)) and very peaceful agrarian revolution (transformation to commercial farming, to a market economy, and to the utilization of new agricultural methods). The development with the family farm as the basic agricultural unit was different from most of Western Europe (large scale commercial farming) and most of Eastern Europe (large manors with quasi-feudal obligations for peasantry) (see also Rueschemeyer et al.

1992: 83-98). The individualization of agriculture was an intervention by the Crown and it implied the weakening position of the nobility that gradually turned into an urban and bureaucratic elite.

The cleavage between urban upper class and peasantry was important in the formation of peasant identity and the rise of social movements and agrarian parties (Olsson 1990). The weakening position of the nobility was also connected with the collapse of the Swedish Empire and during the first decades of the nineteenth century the Nordic countries became a peripheral area in the

expanding capitalist world economy (Wallerstein 1980: 203-226). The early industrialization in Scandinavia was based on success of export industries. The spatial distribution of these industries was considerable and no urban slums emerged. Therefore, the early working class movement consisted of industrial workers and a rural proletariat. In the beginning of the period of mass parties Scandinavia became dominated by the three polar class structure: the urban upper class, the

working class and the peasants. In the absence of ethnic and religious cleavages the Nordic party structure was for a long dominated by these three poles (Rokkan et al. 1970: 120-126; cf also Flora 1999).

Economic Growth and Structural Transformation

While Finland with its fierce Civil War in 1918 and its more retarded, more unbalanced and more sudden economic and structural development somewhat differs from Denmark, Norway and Sweden the overall economic development in the Nordic countries was very fast and from the 1870s all four Scandinavian countries belonged to the fastest growing economies in Europe.

Denmark with its industrialized agriculture reached the average European GDP-level before World War I. Norway with her shipping and Sweden with her versatile industries came to the same level

by the year 1950. Finnish developments were not so expansive. Due to high population growth, one-sidedness of the economy and the serious effects of World War II, Finland’s economic performance has not been very stable. But during the decades following the war Finland belonged to the fastest growing economies in Europe and it reached the high Scandinavian level in the 1980s.

Since then, all the Scandinavian countries have been among the richest countries in the world.

In Denmark and in Sweden, the pattern of transformation from agriculture to industry and services resembled that of the earlier industrialized Europe. During the interwar years the growth of the industry was faster than that of services. When the services also expanded, after World War II, the share of agricultural population was below one-third in Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Finland was a latecomer with half of the economically active population working in agriculture in the late 1940s. After that Finland’s structural development was unusually extensive and robust. During the 1960s and 1970s Finland belonged to the countries where the expansion of the secondary and tertiary sector was simultaneous and the social structure was one of the fastest changing in Europe (Alestalo 1986: 14-39; Alestalo and Kuhnle 1987: 13-18).

Peaceful, Democratic Class Struggle – Consensus Politics

The rising working class was, as the peasantry, considered part of the popular movements and therefore their ascendancy into Nordic politics became, in a European perspective, quite easy – even if there was some resistance from above. There was also from the agricultural revolution onwards a widespread positive attitude to state intervention and agricultural protection agreements partly became prototypes ahead of more far-reaching political and labour market compromises (Castles 1978: 14-15; Allardt 1984: 172, Rothstein 1992). The Nordic model is normally identified by reference to characteristics of welfare state institutions (stateness; universalism) and welfare policy outcomes (equality). But it seems appropriate to add a third important component, namely forms of democratic governance – which refers to the way in – or process through - which political

decisions are made. In this respect, the decade of the 1930s represented a political watershed in all Nordic countries with national class compromises between industrial and agricultural/primary sector interests, and between labour and capital through the major trade union federations and employers’ associations. These compromises also came to be reflected at the parliamentary and governmental level, with political compromises reached across parties representing various class or

for Swedish social reformers (Nyström 1989). Nevertheless, the title of the American journalist Marquis Childs’ contemporary book on Sweden: The Middle Way (1936) captures the path-breaking change of Nordic politics in the 1930s. The politics of the 1930s came to be formative for the kind of Nordic model existing today, though these achievements at the time remained precarious and, from a broader European perspective, peripheral.

A wide concept of the Nordic model must include aspects of the actual democratic form of government – or governance is a better term - in the Nordic countries, the evolution of a specific pattern for conflict resolution and creation of policy legitimacy as basis for political decision- making. This pattern has developed over a long period of time and is characterized by active

involvement and participation in various, often institutionalized, ways of civil society organizations in political processes before decisions are formally made by parliaments and governments, most particularly pronounced through triangular relationships between government, trade unions, employers’ associations or similar organizations in for instance agriculture. This system of

governance may be labeled ‘consensual governance’. The Nordic countries are small and unitary, which make decision-making easier than in big and/or federal states. The case of Finland’s

development towards a consensual democracy has been more dramatic than in the other cases: it is a long distance in politics and time from the Civil War of 1918 to the strongest example of

consensus-building in peacetime Nordic politics represented by the ‘Rainbow Coalition’

government – comprising the parties of the communists, social democrats, liberals, and

conservatives - of the early 1990s, which was established to set the Finnish economy and welfare state right after the dramatic economic downturn partly caused by the break-down of the Soviet Union and an abrupt loss of substantial foreign trade.

‘Consensual democracies’ is a term that generally fits developments since the mid-1930s, and particularly since 1945. Consensus-making has become an important element of Nordic politics partly for the simple fact that coalition governments are the rule – especially in Denmark and Finland-, and - in particular for Denmark, Norway and Sweden – the prevalence of minority coalition governments. A majority of governments have since 1945 been minority governments in these countries. Denmark is a world champion when it comes to minority governments. The Nordic tradition of what can be called ‘negative parliamentarism’ – that the government does not have to be positively or constructively based on a majority in the parliament nor to be installed by a parliamentary majority – has logically appealed to the art of making political compromises:

sustainable political decisions can hardly be made without parties in advance consulting each other,

creating mutual trust, and without government parties consulting opposition parties at any time. The consensual style of Nordic politics and the experience of long-term multiparty parliamentary and/or governmental responsibilities is one reason why it makes more sense to use the geographical adjective ‘Nordic’ rather than – as many of our social science colleagues do – use the narrower, political-ideological adjective ‘social democratic’ when naming the ‘model’. A partial exception to this picture is Sweden, where the Social Democrats throughout the 20th century had a more

dominant position, and where debates on principles of social reforms at times appear to have been more polarized (Lindbom & Rothstein 2004; cf also Loxbo 2007 and Lundberg 2003 regarding pension policy in Sweden).

A note must also be made on the development of Nordic cooperation in the field of social policy – and the consolidation of a Nordic identity - as factors being conducive to the development of the Nordic (welfare) model. The development of formal inter-Scandinavian cooperation between parliamentarians started already in 1907. In this field of policy, the first of many regular joint Scandinavian top political-administrative meetings took place in Copenhagen in 1919. Finland and Iceland joined these meetings in the 1920s, and according to an overview provided by Klaus Petersen (Chapter 5 in this volume) there were over the years 14 such Nordic meetings of social policy makers before the Nordic convention on social security was decided in 1955, after the establishment of the Nordic Council in 1952, and which Finland was ‘allowed’ (by the Soviet Union) to join in 1955. These developments inaugurated sustained Nordic cooperation to this day across many public policy areas. A common, comparative and comparable, Nordic social statistics was established in 1946. Not least the fact that the Nordic countries pioneered transnational regional cooperation after World War II has been conducive to the maturing of a concept of a ‘Nordic

model.’ And this cooperation developed in spite of different foreign policy orientations - differences mainly due to the war experience and geopolitical realities during the Cold War – ranging from NATO-membership in the Western Nordic countries over Swedish neutrality to a friendship pact between Finland and the Soviet Union in the Eastern part of the Far North. It says something about the historical strength of Nordic identity and the strength of relation-building developed both at governmental and non-governmental levels over a long period of time prior to the war that Nordic political cooperation could be strongly institutionalized in the early developing years of divisive Cold War mentality and international relations. After the end of the Soviet Empire, the countries still relate differently to both NATO and the EU, but a common Nordic identity prevails and is given outlet both in common Nordic and in other international fora. Nordic unity on issues of

organizations. The period ever since the early 1930s can in terms of welfare state development in the Nordic countries be characterized as one of domestic consensus-building and common Nordic identity-building. These two elements are crucial pillars of the conception of a Nordic model.

3. THE RISE OF THE WELFARE STATE

Early Social Policy Choices

The beginnings of the modern Nordic welfare states can most meaningfully be traced to the last decades of the 19th century. As elsewhere in Europe, this development was at a general level associated with growing industrialization and urbanization, but also with the political innovation of large-scale social insurance schemes introduced in the German Reich during the 1880s (i.e. nation- building and state-formation). The link between industrialization and social insurance development is not clear-cut: Germany was not the most industrialized country at the time, but in countries with no or little industrialization social insurance did not appear on political agendas.

Quite remarkably, the first major social insurance laws in the Nordic countries were passed at about the same time, in the course of five years, 1890-1895, in Iceland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Finland, and Denmark as the only Nordic country introduced more than one law, altogether three, during the 1890s. Iceland introduced an old age pension (means-tested benefits) law, which was a moderation of the poor law, in 1890 (Olafsson 2005); Denmark a law offering benefits to

‘respectable’ old people in 1891, and a law on subsidies to voluntary sickness funds in 1892, and an employers’ liability act for cases of industrial accidents in 1898; Sweden introduced subsidies to voluntary sickness funds in 1892; Norway passed an industrial accidents insurance law in 1894, where employers were obliged to finance insurance for their workers; and Finland introduced its first law on semi-compulsory industrial accident insurance in 1895. The striking simultaneousness in terms of timing cannot be depicted as a historical coincidence, and can only to some extent be explained by indicators of socio-economic development and political democratization. Denmark was the most urbanized and industrialized country at the time, and in the Nordic context the simple logic-of- industrialism argument appears to hold at a general level in terms of scope of social legislation during the 1890s. But we may ask: what is the logic of being the most industrialized (Nordic) country and introducing an old age pension law (Denmark) and being less industrialized and introducing accident insurance for industrial workers (Norway). The industrialism argument

does not differentiate sufficiently the Nordic countries as to the timing of the first social insurance laws, nor does it reasonably account for the actual type of the first laws. In general, various indicators of democratic development do not perform much better for the explanation of the early social legislation. The democratization factor is multi-dimensional, and it is not obvious which dimension should logically be of greatest importance for social policy development. Norway was the only Nordic country where the principle of parliamentarism had been carried through, while Denmark had the widest enfranchisement, the highest levels of electoral participation and the most developed party system (Kuhnle 1981).

The overall variations in levels of democratization among the Nordic countries and the similarity in timing of the first social security laws reduce the explanatory power of the democratization

argument, and as we know, neither Germany nor Austria as pioneers in social insurance legislation in the 1880s, were European frontrunners as to democratic development. But, as we also know, social insurance legislation can be introduced for a number of reasons and motivations, a popular democratic demand being only one of these. It may be that the combined effect of socio-economic development and a relatively politically mobilized electorate to some extent account for the fact that Denmark on the whole was more active in the field of social policy legislation throughout the 1890s than her Nordic neighbours. But a wider European comparison of socio-economic structures and political system characteristics should caution us against simple structural explanatory factors like industrialization and democratization. Such an analysis can only take us a certain distance on the way to an understanding of the when, how, and for what purposes social security legislation came about. Neither can the similarity in timing of first social insurance laws in the Nordic countries be explained by Nordic political and administrative cooperation and coordination, which hardly existed at the time. It should, however, be mentioned that international cooperation between national central statistical bureaus developed in Europe during the latter half of the 19th century, promoting

collection of various kind of more or less comparable statistics, and associations of national economists – as the then social science knowledge communities – were created at the time and communicated across borders (Kuhnle 1996).

The German ideas of social insurance of the 1880s quickly drifted northwards and had a

demonstrable impact upon Nordic legislative activities, and thus on the similarity of timing of the first Nordic social insurance legislation. None of the Nordic political and administrative authorities were alien to social concerns when the German ‘innovation’ materialized and triggered political

higher on the political agenda than otherwise likely would have been the case . In Denmark a public commission was set up in July 1885, after the passage of the first two social insurance laws in Germany, and after a similar committee, with clear reference to the German legislation, was set up in Sweden in 1884. The Swedish committee was specifically asked to study the German program and propose legislation on that basis. But in both countries, social questions had been discussed and to some extent publicly investigated for a number of years, especially in Denmark. The Danish commission of 1885 resulted in plans for accident insurance clearly inspired by the German

precedent, but – as was the case in Sweden – the proposal submitted in 1888 failed in parliament. Its proposal (of 1887) for state subsidies to recognized sickness funds based on voluntary insurance led to legislation in (July) 1892, and had an impact upon the proposal by the Swedish commission, where a similar law was passed, in fact before the Danish one, in (May) 1891. But these laws did not carry the stamp of Bismarck’s compulsory insurance.

A ‘Workers’ commission’ was set up in Norway in 1885 with the aim of introducing social insurance, and with direct references to the German legislation and the Swedish commission established, and the law on accident insurance in 1894 is the only, modest legislative result of that initiative. Referring to German developments, the Finnish Landtag petitioned government in 1888 to appoint a commission to draft proposals for worker insurance, and one was appointed the

following year with the instruction to outline proposals for accident and sickness insurance. A semi- compulsory accident insurance law was introduced in 1895, while a statute on sickness insurance of 1897 stopped short of offering public subsidies – as in Denmark and Sweden – but only implied governmental auditing of private sickness and pension funds. In Denmark, the first initiatives for old age relief with a financial role for the state originated with a commission established in 1875 and proposals submitted in 1878, i.e. several years before the German Kaiser and his Chancellor Bismarck launched their program in the German Reichstag (in 1881). To put it short: the Danish law on “Old Age Pensions for Respectable People Outside the Poor Relief System” which was passed in April 1891 bore no resemblance to the German law of 1889: its basic principles of financing, organization, and benefit entitlements were totally different.3

Early social insurance/security developments in the Nordic countries were inspired by German developments, while the sequence and contents of early legislation hardly at all followed the

3 In fact, even if the law had been inspired by German examples, this would likely not have been publicly admitted:

this was an era of strong anti-German sentiments in Denmark thanks to the Danish loss of Sleswig to Germany in the Second War of Sleswig in 1864 (cf Chapter 2 in this volume).

German example. To explain early Nordic developments a state capacity perspective may be introduced, and has been attempted in a comparison of the growth and characteristics of the central bureaus of statistics in the three Scandinavian countries of Denmark, Norway and Sweden (Kuhnle 1996, 2007). The development of official statistics is closely linked to the process of state-building and the evolution of a specialized public bureaucracy. Government interest in statistical information increased as a result of efforts to mobilize resources for the maintenance of a standing army and a professional public administration. The development of official statistics in Scandinavia was part of a general European development in the 19th century, and the great breakthrough came after the July revolution in 1830: the period from 1830 to 1850 has been labeled “the era of enthusiasm” of the history of statistics (Westergaard 1932). From the 1850s, national official statistics and publications on various subjects stimulated international comparisons. In Scandinavia, the strengthening of constitutional life encouraged the publication of statistics, and the development was clearly interwoven with state-building processes. That the state could assist in solving social problems, dealing with new needs for worker protection and income security, was generally recognized in Scandinavia at the time of the German social insurance legislation. German legislation came at a time when the Scandinavian countries were politically and intellectually ‘prepared’ or ‘ripe’ for state social action.

The development of the statistical offices, their varying capacity, their orientations and actual experience with collection of various kinds of statistics, historically can be hypothesized to have been an important variable accounting for variations in the type of first social security law

introduced in various countries, i.e. for which social security purpose it was administratively - and possibly politically – easiest to introduce legislation. It may be accidental that Denmark as its first law introduced an old age pensions scheme; that Sweden first introduced sickness insurance, and that Norway and Finland first introduced industrial accident insurance, but the proposition would be that these variations can be explained to a large degree by different characteristics of state

administrative capacity. The statistical preparedness for social legislation differed as well as the capacity to undertake large-scale data collection efforts on short-term basis at the time when Bismarck’s conception of state social insurance was exported from Germany and ‘had to’ be taken more seriously politically. An additional factor is the elite interconnections, or embryonic epistemic communities, within the countries (statistical expertise; academic economists; government officials and politicians). Milieus representing empirical social-scientific knowledge developed within and outside relatively independent governmental statistical agencies. The conception of ‘social

statistics’ was formed. The variable availability of statistics affected policymaking alternatives in the early era of social insurance discourse.

The Breakthrough of Universalism

Denmark and Sweden were the first Nordic countries to introduce universal coverage in the core schemes of the welfare state, sickness insurance and pensions. During the 1890s these countries conducted a reform where the state started providing subsidies to earlier voluntary funds. The same procedure was followed in Denmark and in Sweden in the case of national pensions. Sweden

introduced national pensions in 1913 and Denmark with a series of reforms in 1891, 1922 and 1933.

Especially in the case of national pensions systems Finland and Norway were late-comers introducing national pensions in the mid 1930s. As is presented in Table 1 all four Scandinavian countries implemented general child allowances almost immediately after World War II. In Finland, in Norway and in Sweden these allowances were cash benefits, in Denmark the allowances were composed mainly of tax-deductions.

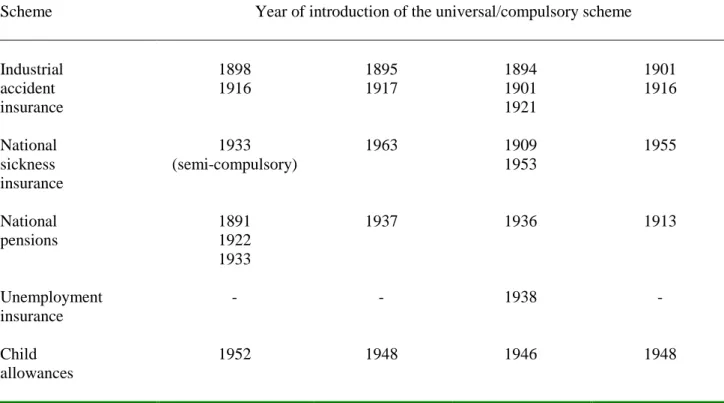

Table 1. Year of Introduction of the First Universal/Compulsory Social Security Schemes in the Nordic Countries (see note under the table).

Denmark Finland Norway Sweden

Scheme Year of introduction of the universal/compulsory scheme

Industrial accident insurance

1898 1916

1895 1917

1894 1901 1921

1901 1916

National sickness insurance

1933 (semi-compulsory)

1963 1909

1953

1955

National pensions

1891 1922 1933

1937 1936 1913

Unemployment insurance

- - 1938 -

Child allowances

1952 1948 1946 1948

Source: Flora & Alber 1981; Kuhnle 1981, 140; Flora 1986 (4), 12, 23, 81, 88, 144, 210. NOTE: The table only lists the laws that introduced compulsory insurance (and/or compulsory contribution to social security schemes. They all end up as universal, but first laws were generally limited in worker or population coverage, except for the 1913 Swedish pension law and the laws on child allowances which were universal from the start.

Among the growing Nordic welfare states rural and non-industrial Finland proved to be an exception during the interwar years. Due to her position as an interface periphery independent Finland belonged also to the new (East-) European states emerging from the ashes of the First World War and of the Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires. As elsewhere in this area land reforms were conducted with highly increased number of small farms. As an inheritance of enclosure movements and the fierce Civil War in 1918 the land question became an important political and social issue, more important than the social question that dominated the political discourse in the other Nordic countries. The last land reform took place after Wold War II. As a result, Finland became a late-comer among the Nordic and Western European welfare states.

Finland was the last Western European country to introduce sickness insurance in 1963 (Flora &

Alber 1981, 59). In the early 1960s, in terms of coverage of major welfare schemes Finland reached the other Nordic countries but in terms of the compensation levels Finland stayed much behind the other Scandinavian countries (Alestalo, Uusitalo & Flora 1985: 192-202).

In presentations of the ‘Scandinavian/Social democratic model’ there has been an emphasis that the social democrats have been the main advocates of universalism in social policy (Esping-Andersen and Korpi 1987: 49-55; Esping-Andersen 1990: 26-29). Kari Salminen’s detailed analysis on the making of the pension policy in the Nordic countries demonstrates that the universalistic pension policy was more on the agenda of the agrarian parties. Social democrats supported a combination of universal and work performance model. They preferred “high pensions for all gainfully employed but not necessarily for the community as a whole” (Salminen 1993: 360; see also Hatland 1992).

The Golden Age of the Nordic Welfare State

The three decades from the early 1960s to the end of the 1980s were the golden age of the Nordic welfare state. During this period there was a catch-up process where Finland, Iceland and Norway, which in the 1950s spent a smaller proportion of their GDP on social security than Denmark and Sweden, bridged the gap to Denmark and Sweden. The real growth of social expenditure was very fast especially in Iceland but also Finland and Norway had higher growth figures than Denmark and Sweden. Despite the different growth figures Sweden remained as the leading Nordic welfare state during these decades. Sweden used more resources on almost all major programs than the other countries. Together with Sweden Denmark was a pioneer of the welfare state even in the 1960s but after that it lost this position and stayed at the level of Finland and Norway in the 1980s. Her

economic growth was slower than in the other countries and unemployment and social assistance expenditures increased from late 1970s faster than in the other countries (Alestalo & Uusitalo 1992:

37-68)

Long term comparisons on the development of public employment are nowadays possible only on the basis of the information coming from the OECD. The data is based on the System of National Accounts which utilizes the concept “producers of government services.” The definition includes central and local bodies in administration, defence, health, education, social services and promotion of economic growth and it excludes most public enterprises. If the public enterprises are taken into account the share of the public sector of the labour force comes almost or over ten percentage points higher in all Nordic countries. With the exception of Sweden, the Nordic countries did not deviate much in terms of the scope of government employment from the other countries in the OECD-area in the 1960s. Between 1970 and 1985 most of employment growth in Scandinavia was a matter of public expansion. Especially in Sweden and in Denmark the expansion was very fast. In 1985 the government employment went beyond 30 per cent of total employment in Sweden, and Denmark came quite close with 30 per cent. Finland and Norway stayed at a much lower level (see Table 8)..

The Nordic countries deviated from other advanced countries because the expansion of the service sector was mainly a welfare state phenomenon. The increasing female labour force participation was paved by the expansion of public employment. Also in this respect Sweden was the leader, followed by Denmark, while. Finland and Norway stayed at somewhat lower level. In Sweden, Denmark and Norway a great proportion of this change came through the increase of part-time work but the fate of Finnish women was full-time work (Alestalo, Bislev & Furåker 1991: 36-56).

Despite some inter-country differences the general pattern of change was quite similar throughout the Scandinavian area. Public sector employment expanded and the welfare state covered the whole population and was able to offer services and cash benefits to people who confronted serious social risks. As the editors of the book The Scandinavian Model (1987) a bit proudly state: “In social policy, the cornerstone of the model is universalism. The Scandinavian countries have – at least on paper – set out to develop a welfare state that includes the entire population. Global programs are preferred to selective ones: free or cheap education for all in publicly owned educational institutions with a standard sufficiently high to discourage the demand for private schooling; free or cheap health care on the same basis; child allowance for all families with children rather than income- tested aid for poor mothers, universal old-age pensions, including pension rights for housewives and

others who have not been in gainful employment; general housing policies rather than “public housing”.” (Erikson, Hansen, Ringen & Uusitalo 1987: vii-viii).

4. CHANGING CONDITIONS FROM THE 1990s ONWARDS

The conditions surrounding the Scandinavian welfare states of the 1990s and early 2000s contrast sharply to those of the immediate post-war period. This is not to say that all that was solid has melted away. For instance, the Nordic countries are still a stronghold of Lutheran Protestantism, the state-church relationship historically always made them different from predominantly Catholic Continental Europe and continues to do so. However, secularization has made headway and the state-church complex is gradually disintegrating. In Sweden, for instance, the Church of Sweden became a ‘voluntary’- even a voluntary welfare - organization in 2000 and actually the largest of this kind as its membership still comprises the great majority of the population. Moreover, in Denmark and Sweden in particular international migration and the changing demographic composition of these populations have made both the Catholic church and various Muslim

congregations important religious associations, also as significant welfare providers. Furthermore, earlier mobilizing social movements such as the temperance movement have declined in importance in Scandinavia while others have become much more institutionalized and less mobilizing, for instance the trade unions, employers associations, and the agricultural co-operatives (Olsson 2001).

New social movements have seen the light of day and thrived in Scandinavia, feminism and

environmentalists in particular, though more as networks than earlier movements (Tranvik & Selle;

2007; Papakostas 2001; cf. Olofsson 1988). Below we discuss five parameters of such large-scale social change more or less conducive to welfare state development: international migration and demographic change; globalization and European integration; economic development;

transformation of the class structure; and finally a note on ideological changes and the rise – and fall? – of a new mode of thinking, or “neo-liberalism”.

International Migration and Demographic Change: From Homogenous to Heterogeneous Societies?

Since Napoleonic times and the decline of monarchical rule, the four Nordic countries have been extremely homogeneous, with the partial exception of Finland, where a Swedish-speaking minority has been recognized ever since the Tsarist era. However, as the Saamis of Lappland has consistently

remained the majority populations, the distinction between various types of settlers is ambiguous.

Until the early 1930s the Nordic countries were also marked by emigration as large numbers of people moved to North America in particular. After the Second World War this pattern was reversed by two waves of migration. During the early post-war decades, labour migration turned Denmark, Norway and Sweden into recipients, while Finland continued to send people abroad, above all to Sweden. During the boom of the following decade labour migration from Southern Europe was encouraged and, thus, the Mediterranean world also provided numerous immigrants.

From the 1970s, the main new settlers in Scandinavia have been refugees, asylum seekers and family reunification migrants, now also coming from further south and east. Though no longer a sender, Finland has continued to be a partial exception to this pattern of international migration. The main pattern, though, is part of a global movement from South to North, and the trend was

accentuated in the 1990s with a large influx of people from war-torn Yugoslavia, later on also from Iraq and Somalia. As we approach the second decade of the new Millenium, less than one million foreign-born in Sweden and almost half a million each in Denmark and Norway (these figures do not include these migrant´s children and grandchildren born and raised in Scandinavia) are contributing to a dramatic demographic reconfiguration. Nordic societies, have ceased to be ethnically homogeneous and are now fairly heterogeneous. This has had effects on class structures (most newcomers were initially working class) as well as on the welfare state as strong attempts have been made to culturally assimilate and socially integrate peoples from afar into the

Scandinavian nation(-state)s. In terms of system integration the guest worker approach was

abandoned early on – active labour market integration programs included language training as well as social studies – in favour of participatory political-institutional solutions including the right to vote in local elections after a few years of residence. There was a strong public concern about the fate of the children of first-generation immigrants and their chances of social mobility (higher education). Ambitious state-sponsored social inclusion programs - from pre-school facilities to service homes for elderly – were started, particularly in the metropolitan areas. Performance has fallen short of expectations. The ”failure of social integration policy” – outsider status or social exclusion in particular in certain metropolitan suburbs (social segregation) – has been a bone of contention between government and opposition (Hajighasemi et al 2006). In a globalized world these welfare states are facing a threat of de-globalization.

Globalization and European Integration

The Scandinavian or Nordic welfare states have always been ‘global’, in the sense of both

participation in the international economy as well as in inter-state organizational cooperation from the regional intra-Nordic to the truly global ILO, UN etc. besides being prepared to learn from foreign examples, such as the locally adapted initially German-, later British, welfare state. Apart from continuity in military security which here simply imply that in 1949 Denmark and Norway joined NATO while Finland and Sweden stayed outside, post-war European integration meant for the Nordic countries at first in particular cooperation within the European Free Trade Association (‘the seven’), from the 1970s a move towards ‘the six’ with Denmark in 1972 as the first Nordic member-state of the then European Economic Community. The same year a popular referendum in Norway turned down this alternative. However, Denmark has been a rather reluctant member and several times voted ‘No’ to deeper European harmonization and integration including a ‘No’-vote in 1992 to the Treaty of Maastricht. It should come as no surprise, that its welfare state has remained distinctly Danish, and Nordic (Hilson 2008; cf also Goul Andersen 1999, Christiansen et al 2006;

Petersen 2006).

With the end of the Cold war again Norway but also Finland and Sweden approached what was now the Single Market, and soon also the European Union. Negotiations opened, and agreements were signed. Thus, from the early 1990s the three countries became much more integrated with the Union and its internal market as part of a larger European Economic Area. Nation-state member- ship in the Union again reached the political agenda and in 1994 there were three separate popular referenda whereby Finland and Sweden decided to join the Union as of 1995 while the Norwegians once again ended up with a ‘No’ on the basis of an advisory referendum. With the start of the monetary union in 1999, however, only Finland joined the Euro-zone (Euro came in everyday use in 2002) while both Denmark and Sweden kept their local currencies. Simultaneously, all three countries have within the European institutional structures been pushing the opening up of the Union eastwards towards former Soviet allies, though. Moreover, they have been actively involved in various practical initiatives in the Baltic Sea area, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania in particular though not primarily as a social policy model (cf. Aidukaite 2004). Nevertheless, as a consequence of recent European integration the Nordic countries have become part and parcel of the European social model but kept most of the distinctiveness of its own part of this model (Montanari et al.

2008).

Economic changes

Thus, the new world – including a new-old Europe – after the demise of the Soviet Union and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet-Russian economy has made the Nordic welfare states even more regional, and global as well. Of the structural changes perhaps most important has been the increasingly free flow of capital. Western credit market deregulation made nation-states – including the Nordic ones except Norway – as borrowers more vulnerable to foreign investors. It is not surprising that the upcoming recession of the early 1990s severely strained the public finances although Denmark managed to keep its spending below the budgetary target. The first half of the 1990s was in particular for Finland and Sweden a period of acute crisis, and the welfare state came in for scrutiny with the rise of globalization as a new figure of thought not least by professional economists. Denmark and Norway, however, were less affected by the general downturn at that time. Growth rates went down across the board while both Finland and Sweden had negative growth for several years during the first half of the 1990s. The Soviet Union was an important trading partner with Finland, and the ties between the Finnish and Swedish economies close. In Sweden, the market value of the private housing and banking sectors almost faded and had to be saved by initially costly but retrospectively innovative policy initiatives. At that time, the financing of the welfare state was in jeopardy. The fiscal surplus suddenly disappeared and public finance balance deteriorated sharply. The resulting deficits created a lot of anxiety about the sustainability of the welfare state and the possibility of financing universal welfare systems. Thus, the welfare state was challenged from within as well as from the outside world. In Finland the economy spun into a vicious circle of negative economic growth rates, a rapidly growing budget deficit, severe bank crisis, increasing foreign dept, depressed domestic demand, tightening taxation, and sky- rocketing unemployment. Nevertheless, no fundamental changes in the main welfare schemes were made but there were a wide variety of minor adjustments and cuts in welfare benefits and services (Alestalo 1994: 73-84).

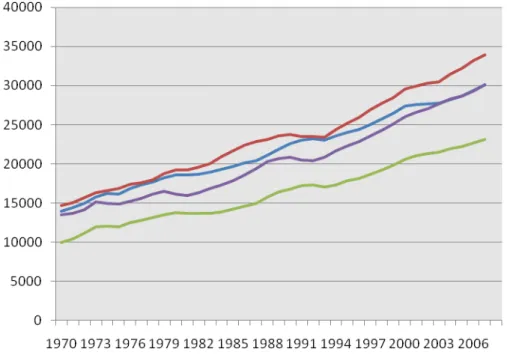

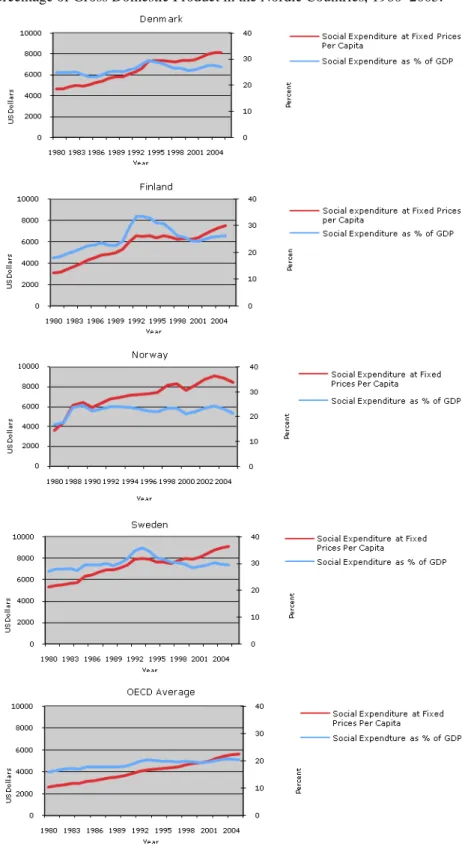

From the mid 1990s, however, not only Denmark and Norway but also Finland and Sweden have shown rather impressive figures of economic development (Figure 1). Modest, steady growth has characterized the period up to the most recent crisis at the end of the first decade of the 2000s, (‘the global financial meltdown’) and the outside world at first rather surprised started to look with envy on the well-financed Nordic welfare states. This has reassured both global and national investors’

confidence in public borrowing and it is probably true to say that the welfare states of the Far North

Figure 1. Gross Domestic Product Per Capita at Fixed Prices, (Constant PPP´s, US dollars) in the Nordic Countries and Different Types of European Welfare States, 1970-2007.*

European Welfare States

Nordic Countries

Source: OECD. National Annual Accounts. Main Aggregates, Gross Domestic Product. OECD.Stat:

http://stats.oecd.org. (April 18, 2009).

* Classification of countries: see Table 3.

Moreover, during the last decade in survey after survey of the global business environment, competitiveness and transparency the Scandinavian countries have consistently scored well, very well to be exact. The world-wide ranking of nations according to indicators of competitiveness made by the World Economic Forum – a list was compiled in co-operation with the Center for International Development at Harvard University – Finland, most severely hit by the recession in the Nordic area in the early 1990s, actually was ranked Number 1 already in 2000, replacing the US which was on top of the ranking the previous two years. Moreover, the other three main countries of the far North of Europe belonged to the ‘top 20’: Denmark, no. 6 (up from 7 in 1999 and 8 in 1998), Sweden 7 (nos. 4 and 7 in previous years), and Norway no 20 (previously 18 and 14). This pattern has continued throughout the first decade of the new Millennium though inter-Nordic ranking has changed over years. According to the Global Competitiveness Index in 2006, the Scandinavian states are among the first worldwide: Finland: 2, Sweden: 3, Denmark: 4, Norway: 12 (World Economic Forum 2006).

Furthermore, the Scandinavian countries had higher labour productivity, defined as GDP per person employed, in the 1990s than the average of EU countries and the USA and labour productivity was rising in the last decade compared to the previous one (Kuhnle, Hatland and Hort 2003). European countries vary a lot in terms of scope of government employment and size of public sector, but the experience of the Scandinavian countries is that also growth in government employment has been quite compatible with expanding welfare states and economic growth; that there is thus no clear-cut relationship between scope of the welfare state and economic performance.

Changes in class structure

Although the making of the Scandinavian welfare state was filled with conflicts between workers’

and farmers’ parties and, on the other hand between these and the conservative, urban-based parties, the absence of the feudalistic structures, the low concentration of landholdings, rural industrialization, non-existing urban slums and non-existing religious or ethnic cleavages, make the important socio-economic structures unitary in Scandinavia. In the period of the making the welfare state Nordic societies were dominated by parties of poor workers, of poor farmers and of not much affluent urban residents. And it is relatively easy to understand that this constituted a unique foundation for universalistic, state-centred and equality-directed welfare structures. In Central Europe, for example, the high level of economic organizations, guilds, mutual benefit organizations,

different kinds of trade unions and greater variations in affluence, a more fragmented system emerged (Alestalo & Flora 1994: 60-61; see also Allardt 1984).

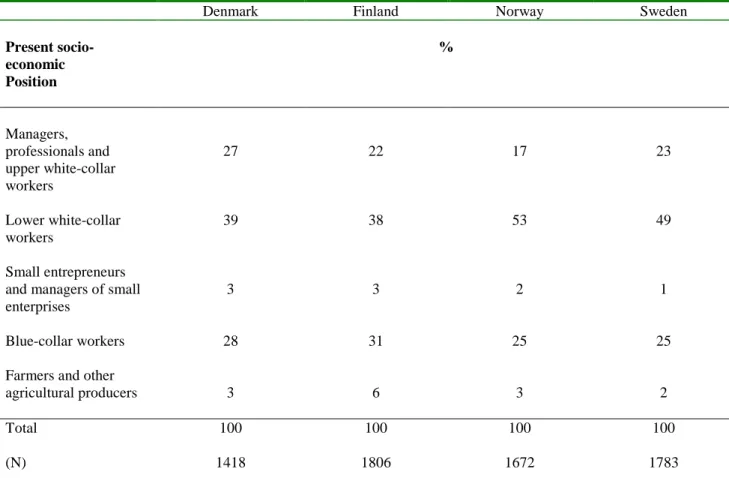

Table 2. Economically Active Population According to Present Socio-economic Position in the Nordic Countries, 2006.

Denmark Finland Norway Sweden

Present socio- economic Position

%

Managers, professionals and upper white-collar workers

27 22 17 23

Lower white-collar workers

39 38 53 49

Small entrepreneurs and managers of small enterprises

3 3 2 1

Blue-collar workers 28 31 25 25

Farmers and other

agricultural producers 3 6 3 2

Total 100 100 100 100

(N) 1418 1806 1672 1783

Source: European Social Survey 2006. Note: Includes only civilian employees, population over 15 years of age.

http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/ (February 18, 2009).

Classification (ISCO 88): Managers …(1000-1239, 2000-3000, 3142-3144); Lower …(3100-3141, 3145-5220);

Small …(1300, 1310, 1312, 1319); Blue-collar …(6000, 6100, 6140-9330); Farmers …(1311, 6110-6130).

The fast economic growth, rapid changes in the social division of labour and high increase of educated people during the decades following World War II have transformed the structural base of the Nordic welfare states. The number of farmers has almost diminished and there has been a strong decline in the proportion of manual workers. Economically active people in present-day Scandinavia are mostly various kinds of white-collar workers among which well-educated and well- off middle class people have a high proportion (Table 2). Although the coding procedure used in Table 2 may exaggerate the share of upper white-collars with some percentage points the class structure in the Nordic countries do not deviate much from that in Continental Europe or in Great Britain (Leiulfsrud et al. 2005, 28-37). Changes in class structure are among the most important challenges arising from the changing preconditions of the Scandinavian welfare state.

Ideological and Political Changes – The Age of Neo-Liberalism?

Finally a note on epochal changes in mindset: in recent decades the new global set-up and its cultural repercussions has entailed some changes affecting also the geopolitical status of

Scandinavia and its welfare state model. The earlier predominantly West-East Global Cleavage has been replaced by a North-South divide: the North has absorbed the old West and the rest is South, although the new East – East, South-East and in the most recent decade even South Asia (India) – gradually have come to challenge that axiological division. Moreover, in the Northern camp, on the fringes of the new-old world the Far North has set itself apart as a somewhat different world of Welfare States. With the new wave of globalization, at least since the 1990s the Scandinavian model has come under increasingly closer international scrutiny and seems to have had to ‘adapt’ or adjust to the new secular mode of global social organization: neo-liberalism. To some extent this is true. Rather ironically, also in Scandinavia Social Democrats came to sing neo-liberal songs. In the social policy debate of the 1980s and 1990s, many commentators and researchers began to argue that, if the welfare system grows too large, it risks perverting incentive structures in both working life and society in general. Welfare breeds a dependant underclass. Pundits and professors alike pointed to what they considered to be excessively generous sickness and unemployment benefits, and to the manifold opportunities for drawing disability pensions, and they claimed that this excessive generosity resulted in various forms of over-utilization and over-insurance. Such

spokesmen have maintained that the assumption by the state of far-reaching responsibilities for the well-being of citizens leads to a moral weakening of the various networks of civil society - families, neighbourhoods - and that the persons receiving assistance are relieved of responsibility for their own actions. They claimed that social policy, if anything, worsens the problems it sets out to solve.

This critique is by no means new, of course; quite the contrary; the debate over the ‘spirit of welfare dependency’ raged already at the dawn of social policy, both in Scandinavia and elsewhere but took a new turn with the rise of the global neo-liberal agenda. The next step was to start the

“fundamental reassessment of the role of the public sector” (Saunders and Klau 1985: 12).

What was new was the renewed energy with which this critique was put, together with the fact that those expressing it was also be found on the left of the political spectrum (Kuhnle and Hort

2004:13-17). Growing macro-economic imbalances in the aftermath of the so called oil crisis of the mid-1970s, made the fiscal crisis of the state a recurrent theme in the discussion about the

academic economists. All over the Western world, important segments of this profession turned towards a critique of the earlier dominant paradigm of Keynesian macro-economic planning in favour of monetarist laissez-faire neo-classical economic thinking. In such circles, the welfare state was no longer looked upon as a solution to but rather as a source of the crisis. Perhaps less so in Scandinavia than in other parts of the developed world, nevertheless this strand of thought became an influential voice in the public debate. Domestic critics of the welfare state in Scandinavia argued that the growth of the public sector had caused stagnation in the growth of the overall economy as increased taxation crowded out private investments and private entrepreneurship (Dowrick 1996; cf also Agell, Lindh and Ohlsson 1997). For a while this was mainly an academic critique of national policy-making although a tax revolt in Denmark already in the early 1970s pointed out a weak spot in the welfare state consensus (Norby Johansen 1986). However, with growing crisis symptoms all over Scandinavia the impact of this kind of thinking widened. But it was not until the early 1990s, when the economic crisis severely hit two of the national economies of the region, Finland and Sweden, that the true possibility of the neo-liberal formula became visible also in the heartlands of the welfare state, and the academic economists for a while came to dominate policy reorientation (cf Lindbeck et al 1994).

However, a universal welfare state can be seen as an experiment in solidaristic behavior on a massive scale (Kumlien and Rothstein 2005; Rothstein 2001; Baldwin 1990). If benefits are widely and systematically abused, or perceived being done so, this solidarity comes under severe stress.

Thus, the solidarity necessary for the preservation of the system is not absolute but conditional. If the profession of academic economists in large numbers left the post-war consensus behind the welfare state, a different pattern is to be found in the Scandinavian population at large. While the academic as well as part of the political elite has questioned the efficiency of the welfare state, in contrast the attitudes among the great majority of the populations in Scandinavia has remained solidly in support of most social programs and in particular universal social programs (Nordlund 2002; Svallfors 1996). Thus, with an impressive economic performance from the second half of the 1990s, gradual changes in the underlying social structure and a rather stable political system slowly integrating into a larger Europe, it should come as no surprise that during the present decade the Scandinavian model has regained something of its status as an alternative or supplement to the dominant – global or American – societal model. In a fragmented Europe in recent years, it is the performance of the universal welfare states of the Far North, not the continental or blairite Anglo- Saxon types, that has injected new energy into the European Social Model.

Summarizing section four, the Scandinavian welfare model, while having been put on some severe tests in the early nineties, particularly in Finland and Sweden, has been able to revitalize and maintain its core elements of universality and societal and economic stratification. We refute perceptions that see the end of the Scandinavian welfare state and attempt to explain why the welfare state in the Nordic countries has not crumbled. We will look at institutions and outcomes from a macro-perspective with the goal of showing broad policy developments. Using selected data, we will illustrate where changes in the Scandinavian welfare model have occurred and will draw some tentative conclusions as to the regional influence of globalization on the Scandinavian welfare model.

5. SCANDINAVIAN WELFARE STATES IN THE 1990s AND 2000s

Initially the 1990s was a period of crisis while the first decade of the new Millennium has witnessed a renewed international interest in the Nordic Model. Gradually the welfare state has regained some of its strength. Approaching a new global economic crisis the solutions to the financial crisis of the early 1990s – in particular as regards the banking sector – have become another Scandinavian model for the world to follow at the entrance into a new period of crisis or “financial meltdown”.

Focusing on welfare and organization between two crises - in which ways have these welfare states changed: how and why? First we will focus on policy developments, then on social expenditures and welfare cutbacks and reorganizations. What about outcomes: poverty and in-equality?

‘Work-, Woman and Family-Friendly’ Policies Including Increasing ‘Child-Friendliness’ but less ‘Immigrant Friendliness’?

Economic growth is possible with a number of welfare state constructions, of different scope and generosity including the type characteristic of the Far North. Growth and efficiency are not the sole goals of Scandinavian national welfare politics but they have definitely been reinforced, even reinterpreted, during and after the crisis of the 1990s. Still, they are not the only political and social goals. Some goals may even partly be considered hidden such as pro-natalist ones (e.g.

demographic growth or policies that may promote increased fertility rates). Politics and welfare state construction are also about equalization of life chances, social justice, social security, social

and dynamics of economic development, climate of investments, etc., but also to political

preferences, ideologies, interests and values. Thus, what kinds of welfare state policies are possible is also at all times a question of what is considered desirable by parties, voters and governments, and what is considered desirable – what the state can and ought to do (Rothstein 1994) – is a question of political and cultural context (norms, expectations, value structures: fairness, justice, cohesion, stability, material and physical security, well-being, etc.) as much as a question of level of economic development and theories and knowledge of pre-requisites for economic growth and efficiency.

Among the many characteristics which can be ascribed to the Scandinavian type of welfare state is its ‘work-friendliness:’ the persistent efforts to develop social security and labour market policies which promote ‘full employment’ and which have helped put the Scandinavian countries on top of the list of employment ratios of OECD countries. Being among the most comprehensive welfare states, providing income transfers and services on a more universal basis than elsewhere in Europe, it is interesting to note that all of the Nordic countries showed increasing labour productivity in the 1990s compared to the previous decade, and that the level was everywhere higher than for the USA and for the EU average (Kuhnle, Hatland & Hort 2003). Among European welfare states, the Scandinavian countries were also the most ‘women-, family- and child-friendly’(Hernes 1978;

Esping-Anderson 1999; 2002; 2005 ), i.e. in terms of having developed policies conducive to labour force participation of both women and men in families with children and/or other care responsibilities – which may be another way of looking at the degree of ‘work-friendliness’ of welfare states. In one way, such government schemes may be considered both ‘work-friendly’ and

‘family-friendly’. If families are relieved of some of their ‘burden’ (itself a contested concept) as care-givers (for their young, old and sick family members) labour market activity and labour mobility can increase, and thus also economic productivity and growth. Government social policies can provide the basis for flexible solutions for families, for employees and for firms. Social policies can make it possible, if desired, for both husband and wife to combine family obligations with full (or part-time) gainful employment. The Scandinavian countries have for long had the most

extensive provision of (local) government welfare and care services for children and the elderly of Western welfare states (Kohl 1981; Anttonen & Sipilä 1996: 87-100; Kautto et al. 1999). When referring to policies oriented towards gender equality, Scandinavia usually comes to mind first.

Daycare for even the youngest children, generous parental leave for mother and father and

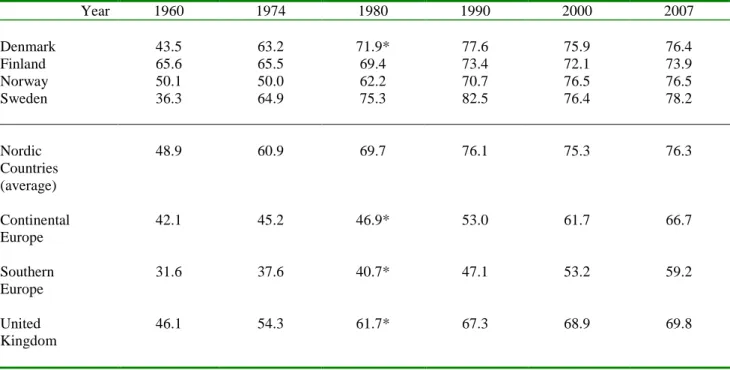

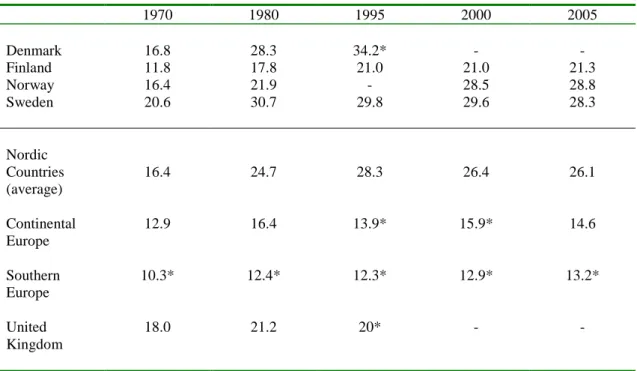

numerous further support programmes have created a mythical landscape of Scandinavian gender equality for women worldwide. As the Table 3 below show, the Scandinavian states have been