Phrases and Adverbs in Semitic '

By Na'ama Pat-El and Alexander Treiger 1. Introduction

Most Semitic languages show a reflex of a pronoun with an initial Ö70 1with the function of determinative, relative pronoun, and demonstrative, though not all languages exhibit all functions. This pronoun was recently recon¬

structed to Proto-Semitic (henceforth PS) by John Huehnergard (2006) with the original function of relative-determinative. Huehnergard (2006, pp. 116-118) established the connection between the East-Semitic pronoun and the West-Semitic one and pointed to their similar function and distribu¬

tion. Except for Eblaite and Old Akkadian, it is no longer inflected for case, but may be inflected for gender and number. 2

The pronoun is considered to always be a bound form that can stand be¬

fore a noun in the genitive or before a clause. It can be used with or without a nominal antecedent (Huehnergard 2006, p. 114). This, of course, may explain its later developments in the daughter languages into a relative pro¬

noun and marker of the genitive relation between nouns.

However, there are instances of the pronoun followed by a prepositional phrase or an adverb, like in the following examples:

1. Syriac: "emar. .. cal dekrä d-b-ïlànà da-hwä l-debhä hläpaw hy (Eph. in Gen. 6, 9—10) "He told ... about the ram in the tree, which became the sacrifice instead of him."

* We wish to thank John Huehnergard of Harvard University and Gideon Goldenberg of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem for their useful comments on an earlier version of this paper. Any remaining errors are purely ours.

1 Only East Semitic shows a reflex of the latter.

2 Arabic shows partial inflection with only gender and number distinctions, where the dual shows also two cases: nominative and oblique. Gaaz also shows gender distinc¬

tion, though not number (common pl., \illa> and 1. singular, stem from a different root). In Hebrew there are only remnants of gender distinction in the pattern rnd-zze (with the relative ze, not the demonstrative), where the feminine mä-zzöt is only attested with the verb 'to do'. See Huehnergard/Pat-El 2007, for details.

2. Arabic: 3à-l-kasu llatïfï yadika "ajmalu "ami l-qalamu (al-Jähiz, Kitäb al-Tarbï cwa-l-Tadwïr in: Rasa il al-Jähiz ^Cairo 1399/1979, III, p. 89)

"Is the cup in your hand more beautiful or the pen?" 3

3. Akkadian: kaspu u-sïpàti gabbi sa ittiya ana agruti attadin (VOS III 19, 12-13, apud Aro 1963, p. 403) "alles Silber und alle Wolle, die ich hatte, habe ich den Mietleuten gegeben".

Adverbs and prepositional phrases can function as predicates in nominal clauses, but require an overt subject. In some languages they can also function as the object ofa bound form in construct patterns (see discussion below). 4 The problem is how can we account for their appearance in this pattern and what is their function here. Two explanations have been offered, both agreeing that they are part of an 'elliptical' clause. The first explanation is that the prepositional phrase is an adverbial phrase in a sentence that was omitted; the second explanation is that it is a predicate in a sentence whose subject is the relative pronoun.

We disagree with both explanations. In what follows we will examine the arguments in favor of these explanations and show them to be inadequate.

We will further offer our own explanation which we think does better jus¬

tice to the data and the known structure of the Semitic languages. We hope that our explanation will shed light on the PS situation. 5

2. Discussion Previous Studies

As was mentioned above, there are two common explanations for the func¬

tion of the prepositional phrase in the pattern. In addition, the question of the syntactical function of the relative pronoun is addressed by some schol-

3 Some manuscripts lack the relative pronoun }allatï.

4 In Hebrew and Syriac such patterns are not uncommon; consider the following ex¬

amples:

- Syriac: mdytay qallïlaït (Mart. I, 79,10apud Nöldeke 165 §207) Those who die quickly.

- Hebrew: koIhose bo (Ps. 2:12) All who take refuge in Him.

5 The Biblical Hebrew data pose aproblem. Hebrew does not use the PS relative-deter¬

minative as a relative pronoun, but rather ag r a m m a t i c a 1i z ed noun, >aser (Huehnergard 2006). Naturally, this noun never had apronominal inflection. However, it isimpossible to know what kind of inflection, if any, itdid have. Two possibilities seem reasonable: either it had the same syntax as the PS relative pronoun, i.e. stood in apposition to its antecedent, or it was marked according to its syntax in the relative clause, in which case it differs from PS and other Semitic languages. Since this is aproblem which is yet to be solved and does not have any substantial effect on our discussion and conclusions, we will not use the Hebrew evidence as part of our a r g umentation,but solely as an extra note, where relevant.

ars, albeit indirectly. Both issues are closely related, as will be shown below.

In what follows we will review these explanations pertaining to various lan™

guages and argue that they are structurally impossible.

The Prepositional Phrase is an Adverbial Complement

Recently this explanation was raised for Syriac and Hebrew. Wertheimer (2001, 2005) argues that the prepositional phrase is an adverbial complement in an elliptical relative clause. She describes these patterns as lacking a verb or a copula. 6 Either way, Wertheimer's explanation presupposes complete deletion of the nexus, i.e. both the subject and the predicate (verbal or nomi¬

nal) are missing. Thus, according to her, a sentence such as 3a }'k me Uta d- Gabrïël da-lwät Maryam "according to Gabriel's speech to Mary" should be reconstructed as ''rd-etamrat Iwät Maryam or *d-emar Iwät Maryam (2001, pp. 269-70). 7 According to this analysis, the prepositional phrase is ad-verbal if preceded by d-> but ad-nominal otherwise.

This explanation is not possible. Sentences without a subject and a predi¬

cate are not sentences, since they lack nexus. In no Semitic language, includ¬

ing Syriac, can an adverbial phrase constitute a sentence by itself. Since there is no reason to assume that relative sentences have a different syntax than matrix sentences, there can be no relative sentences consisting of an adver¬

bial phrase alone.

The Prepositional Phrase is a Predicate

The more common view is that the prepositional phrase is a predicate of a nominal sentence. This view is represented, for example, by Gai, who in his dissertation on adnominal modification in Semitic, claims that there are only three syntactic functions that prepositions can perform in Semitic: ad-verbal, ad-nexal, or predicative (1978,p. 25 fn). A prepositional phrase after an adjec¬

tive is ad-verbal, because such a pattern is comparable to a verb followed by a

6 For the inaccuracy of the term copula in Syriac see Goldenberg 1983.

7 In alater discussion (2005), Wertheimer divides these patterns into two types: el¬

liptical relative clauses with a concrete antecedent and elliptical relative clauses with an abstract antecedent. The formal difference is allegedly the possibility of abstract nouns to appear with possessive pronouns. However, abstract (and déverbal) nouns can appear with or without the possessive suffix: bay ye da-Walam "eternal life" vs. hubbeh d-seday hon

"his love for them" and so can the so-called concrete nouns, so in effect there is no formal distinction here. Déverbal nouns and nouns that denote action tend to take pronominal suffixes to mark their subject, while other nouns do not normally have that option. There¬

fore the fact that we so often find such suffixes on déverbal nouns isafeature of the syntax of such nouns, not of the pattern.

prepositional phrase8and cannot be replaced by a relative clause;a prepositional phrase after a noun can only be predicative (1978, pp. 28-29). Therefore, he suggests (1978, p. 176) calling any prepositional phrases which modify a noun

"asyndetic relative clauses", while prepositional phrases after a relative pronoun are accordingly syndetic relative clausesin which they serve as the predicate.

Let us now turn to discussions of particular languages, starting with Ara¬

bic. The pattern is very common in all stages of Arabic, for example:

4. wa-lahunna mitin lladï calayhinna (Qur 5än 2:228) "They (f.) have the same rights [lit. what is due to them] as duties [lit. what is incumbent upon them]." 9

5. 3ild l-kabanati llddïna tamma (NT, Acts 11:30, apud Blau 1966-1967, p. 571) "to the priests there" (=Peshitta NT l-qassïsë d-tammäri).

6. "az-ziyddatu llatï qablahd bi-manzilati z-ziyddati llatï ft I-gam i (Sïbawayh, I, p. 4:19-20 Derenbourg) "The addition before it is equiva¬

lent to the addition in the plural."

Surprisingly, despite the fact that this pattern is very widespread in Arabic, modern grammars of Arabic hardly mention it. 10When they do, they usually analyze it as an elliptic relative clause with the prepositional phrase as the predicate and with the subject (the nominative resumptive pronoun) omitted. 11

Why is the subject omitted? According to Reckendorf (1895, p. 61 7f., 1921, p. 428f.), this is a part of a general process where the relative pronoun loses its independence vis-à-vis the relative clause and takes, virtually but not formally, the case required by the relative clause as in Indo-European languages (although formally, at least wherever this can be ascertained, i.e.

in the dual, it still agrees in case with the antecedent). A concomitant devel¬

opment is that the resumptive pronoun, having surrendered its function as a case marker to the relative pronoun, is easily omitted. In such cases, the rela¬

tive pronoun has, according to Reckendorf, a double syntactic function: it carries both the case of the antecedent and the case required by the relative clause, with only the former being formally represented. 12

8 E.g. apattern with an adjective: hinnë häkäm 'at ta mid-Dànï'ël (Ezk. 28:3) "you arewiser than Daniel", and the same pattern with averb: way-yehkam mik-kol ha - *ada m (lKg. 5:11) "andhe was wiser than everyone".

9 For more examplesseeQur'an 3:96; 6:92;22:46.

10 De Sacy even goes as far as to explicitly prohibit the pattern in the case of Ara¬

bic:"Si Pattribut [of the relative clause] étoit sous™entendu et exprimé seulement par un terme circonstantiel, on ne pourroit point faire l'ellipse du pronom personnel [viz. the re™

sumptive pronoun]. On nepourroit pas dire, ra'aytu lladï fï d- dar i; il faut nécessairement dire,ra "aytu lladï hu wafï d-dàri. (1831,II,p. 347, §599). This is corrected by Fleischer (1885-1888,1, p. 701 f.).

11 See, for Modern Standard Arabic, also Cantarino 1974-1975, III, p.167, §230C.a.

The problem with this explanation is that it does not explain why nomi¬

native resumptive pronouns are omitted much more frequently in relative clauses with a prepositional (or adverbial) predicate than in those with a nominal predicate. 13 In fact, cases of omission of a nominative resumptive pronoun in relative clauses with a nominal predicate are exceedingly rare; 14 such patterns as**('al-waladu) lladï gamïlun or **('al-waladu) lladï kätibun are ungrammatical and do require a resumptive pronoun: Çal-waladu) lladï huwa gamïlun or Çal-waladu) lladï huwa kätibun. 15

Wright (1896, II, p. 322B-C, § 175a) offers an alternative explanation. He notes that

[i]n nominal [relative] sentencesof which the predicate is an adverb,or a prep¬

osition with its genitive, depending on the [implied]idea of being ..., the virtu¬

ally existing subject ofthe substantive verb [i.e.the implied käna] suffices to connect the clauses, without any separate pronoun being expressed.

Most of the examples given are with ma or man (e.g. marartu bi-man tamma

"I passed by him who is there / those who are there"); 16 the only example with "alladï is "inna "awwala baytin wudia li-n-ndsi la-lladï bi-bakkata (Qur 5an 3:96) "the first sanctuary [lit. house] erected for the people is indeed the one in Bakka". 17 Wright's explanation is related to Fleischer's claim (1885-1888, I, p. 702) that every adverb of place or time and every preposi¬

tion governing a genitive and standing formally or virtually in the accusa¬

tive is dependent on a verb or a verbal noun with the basic meaning of being

12 Reckendorf gives the following examples lor the omission of the nominative resumptive pronoun in relative clauses with prepositional predicate: 'ila hada r-raguli lladï fi l-higdzi (Ibn Sad) "zu diesem Manne, der im Hedschäz ist"; sallä r-rak (atayni llatayni qabla l-magribi (Ibn Sacd) "er betete die beiden Rak'as, die vor dem Abendgebet kommen"; fï l-'alfayni IIaday ni ma'ahü ( 5al-TabarT) "mit den 2000, die bei ihm waren";

'alladîna min qablikum (Qur'än 2:19) "die vor euch waren". These cases are grouped to¬

gether with those in which an accusative resumptive pronoun is omitted, e.g. huma l- gazdldni lladdnï dafanat gurhumun fïhi (Ibn Hisam) "das sind die beiden Gazellen, die

die Gurhumiten dort vergraben hatten" instead of dafanathumd.

13 They are habitually omitted in relative clauses with averbal predicate too, but this is due to the fact that anominative pronoun isinherent in the finite verb (Recken do re 1895, p. 618, GOLDEN be RG 1985, pp. [171-172]).

14 Grammar books (e.g. Wright 1896,II, p. 322D, de Sacy1831, II,p. 346, §598) repeat the following two examples: huwa lladïfï s~samai *i la hun wa-fi l- ardi 'ilàhun (Qur'ân

43:84) "Heis the onewho is God in the heaven and God upon the earth"and man yuna bi- l-hamdi lä yantiqbi-md safah un "he who cares for praise, does not speak whatis foolish".

According toWright and de Sacy, this happens more oftenin longer relativeclauses.

15 See examplesin Recken dore 1895, p. 616.

16 However,in de Goeje'sadditionto Wright's Grammar (Wright 1896,1,p. 277A-B,

§353*),this manis treated as an indefiniterather than arelativepronoun.Similarly,in Wright's

own treatment of the mä... min construction (Wright 1896, II, pp. 137D-138A,§48g).

17 Bakka is usually interpretedas equivalent to makka, Mecca.

or becoming, whether actually expressed or implied. 18 Fleischer argues that since in the examples given the indication of place as a predicate is in™

separable from the idea of a subject located there, it becomes unnecessary to name the subject itself in the form of a resumptive pronoun. 19

This explanation does not hold water for it would imply that an adverb of place or a preposition governing a genitive, e.g. hundka or fï d-ddri, would in itself constitute a grammatical sentence, which is of course not the case, for it is never permissible to omit the subject of a nominal sentence in a non- relative syntactic context. 20

This structure occurs quite often in Aramaic from its earliest dialects and was almost unanimously analyzed as an elliptical relative sentence. Segert (1975, p. 327, §6.2.5.2.3.) adduces several examples where according to him the relative pronoun functions as the subject of a nominal clause.21 Note the following examples:

7. khny" zy b-yb byrf (Cowley 1923, p. 30, 1) "die Priester, die in der Festung Jeb (sind)".

8. bët "Haha dï b-ïruslem (Ez. 4:24; 5:2, 16) "the house of God in Jerusa¬

lem". 22

9. u-h-gubrïn gibbdrë hayil dï bd-haylëh (Dan. 3:20) "and to the strong men in his army". 23

Bauer and Leander (1962, p. 356, § 108e) analyzed this pattern asa nominal sentence the subject of which is the relative particle dï. They added, however,

18 Cf. Gai (1978, p. 25, fn) where the same ideas are presented as the general rule in Semitic.

19 "Jedes Orts™ und Zeitadverbium und jede Präposition mit dem von ihr regierten Genitiv hängt, wie alles formell oder virtuell im Accusativ Stehende, von einem Verbum oder Verbalnomen mit dem Grundbegriffe des Seins oder Werdens ab. Dieses logisch nothwendige Antecedens wird nun entweder wirklich ausgedrückt, oder ist von selbst gegeben da, wo einer der genannten Satztheile, wie hier, als sibhu gumla, d.h. Quasi-Satz

das vollständige Prädicat eines Nominalsatzes, oder, wie anderwärts, die sifa, das Ad- jectiv oder die qualificirende Apposition eines indeterminirten Hauptwortes bildet. ...

[DJer von der Ortsbezeichnung als Prädicat untrennbare Begriff eines daselbst seienden Subjects macht die Nennung desselben in Gestalt eines auf "alladl zurückgehenden Pro¬

nomens entbehrlich." (Fleischer 1885-1888,1, p. 702).

20 Except, of course, when the sentence gives an answer to aprevious question, such as

3ayna zaydun} hundka "Where is Zayd? - There".

21 Segert notes, however, that this function is a development in Aramaic: "Die Ver¬

wendung als Subjekt in Verbalsatz ist bereits in dem ältesten F (r üh)A (ramäi schen) und Ja('udischen) belegt, während dieses Pronomen als Subjekt des Nominalsatzes etwa paral¬

lel mit dem zur Annexion des nominalen Attributes verwendeten Pronomens gegen Ende der F(rü h)A(ramäischen) Periode auftritt." (1975, p. 326, §6.2.5.2.1).

22 This pattern is common in Ezra, see also 5:1, 6, 10, 14, 15,17;6:2, 5, 6, 9,18; 7:15, 16, 21,22,25.

23 This pattern is relatively rare in Daniel. See also Dan. 6:14.

that by omitting the relative particle, the preposition becomes attributive (pp. 314^315, § 91 a; p. 356, § 108f Anm. I). 24

Fitz m ye R in his grammatical survey of the Sefire inscriptions lists several relevant examples, such as the following:

10. Sefire: cdy yzy b-spr" znh (I B [23], 28, 33 and passim) "the treaty in this inscription".

He analyzes (1995, p. 201) these examples asa relative clause where zy is the subject of a nominal clause. He too attributes to the preposition primarily the function of an ad-verbal or ad-sentential modifier. 25

In Syriac we find an abundance of examples and indeed most references to this pattern are found in the grammatical literature about this language.

Consider the following examples:

11. metmathd taVltd d-sab cd ddrayhon cdammd I-me Hay Lamk bar Qd 3en da-lwat nesawhy(Eph. in Gen. 4, 17-19) "The story of their seven gen¬

erations stretches up to the words of Lamech son of Cain to his wives."

12. bdtar hdlën "ernar cal pursdnëh d-Löt d-men "Abraham w- cal sebyëh d-cam sdômdyë w-mestawzbdnutëh da- b-y ad "Abraham (Eph. in Gen. 5, 9-10) "After these things he spoke about the departure of Lot from Abraham and his captivity by the Sodomites and his salvation by Abraham."

Some scholars, like Nöldeke and Brockelmann, analyzed this pattern in Syriac as a relative clause of some sort.26Muraoka (1997, p. 72, §91.3) re™

mains uncommitted and merely gives a short descriptive note: "A preposi¬

tional phrase expanding a noun phrase is often introduced by the proclitic d-\ He does not explain what the syntactical function of the pattern or the particle d- is.

As was mentioned above, Gai (1978, p. 176) holds that all adnominal prep¬

ositional phrases are asyndetic relative clauses of which the prepositional phrase is the predicate. This cannot possibly be the explanation in Syriac. In Syriac, nominal sentences, the predicate of which is not verbal or participial, are formed with an obligatory pronominal subject clitic on the predicate (cf.

Goldenberg 1983, pp. 98-99), e.g.:

24Rosenthal (1983)did not refer to this pattern specifically.

25Fitzmyer (1995, p. 214):"... the preposition functions inthese texts most frequently to introduce a phrase that is an adverbial modifier of the sentence asa whole or of the verb." There are some examplesof prepositions as noun modifiers on p. 215.

26 Nöldeke (2001,p. 289, §355): "short adverbial adjuncts to a noun are generally turned into the form of relative clauses, by means of d-\ Brockelmann (1908-1913, II, pp. 96-97) also called the pattern relative: "Adverbiale Bestimmungen eines Nomens wer¬

den häufig durch d- zu einem selbständigen Relativsatz erhoben."

13. 3atton bi-tton w-ena bkon-na (John 14:20) "You are in me and I am in you."

Without this pronoun, the prepositional phrase cannot be understood as the predicate, thus in the sentence yutrdna hw lan "it is an advantage to us" (apud Goldenberg 1983, p. 101), the prepositional phrase is not the predicate; but the noun yutrdna is, since it is marked by the clitic personal pronoun as the predicate. Therefore, any explanation that attributes a predicative function to the prepositional phrase in our pattern is at odds with the general struc¬

ture of Syriac.

Moreover, in Syriac, participles and adjectives can also be used as adverbs.

In this function they are in the absolute state and are not inflected for number and gender, unlike predicative and attributive participles; thus, in nurd hy saggttd "it is a great fire" there is agreement between the noun (fs)and the ad¬

jective while in saggïtlë hwët I saggïtalyd hwët "I was very young" the form of the adverb is unchanged whether the first person is feminine or masculine.

Such uninfected participles and adjectives are also found preceded by a relative particle in Syriac: mhütd rabbtd d-tdb (Judges 11:33) "a very severe blow".27 Note that the antecedent of the relative is feminine and the adjective has a default form (masculine sg. abs.). Though, following Gai's analysis, the participle could be considered predicative, this should be ruled out, since it is not in gender agreement with its alleged subject. 28

Ugaritic also shows the same type of structure with the relative particle followed by a prepositional phrase. Consider the following:

14. tql d cmnk (apud Tropper 2000, p. 899 §97.112) "der Schekel, der bei dir (deponiert) ist".

15. adrm d b gm (apud Tropper 2000, p. 899§ 97.112) "die Vornehmen, die auf dem Dreschplatz waren".

Tropper lists these sentences under nominale Relativsätze' and compares their structure to the predicative particles it and in.

In G3 C3Ztoo remnants of a similar pattern occur. Lambdin (1978, p. 107) quotes phrases like za-matana-ze hdymdnot "such faith" (lit. "faith to the extent of this") or za-kama-ze s'eltdn "such authority" (lit. "authority like this"). These phrases are complexes made of the relative particle za and a prepositional phrase. Lambdin does not offer an analysis of these exprès -

27 Cf. Heb. makkd gddöld m 9'öd.

28 Wertheimer (2001) argues that this is arelative clause. She translates d-tdb "which is very" (288). Such a clause does not exist in Syriac. If this were a relative clause, itwould be translated as "which is good". Such a translation is, as was explained above, out of the question here.

sions, but translates them as if they were relative clauses. These phrases are analogous to the Syriac d-ayk hand "such" (lit. "like this"), which usually precedes the noun qualified by it. 29

In Eastern Semitic we also find this structure. Aro (1963, pp. 398-399) showed that prepositions can modify the noun in Akkadian, as the com¬

mon epistulary style tuppi PN ana PN2 "a letter from PN to PN 2" and many other examples most of which are locative. Aro (1963, p. 402) argues that in many cases it is not clear whether a prepositional phrase modifies the noun or the verb and this 'mix-up' must be made clear:

Jetzt macht aber auch das Akkadische von dem Ausweg Gebrauch, den wir schon obenim Aramäischen und Äthiopischen kennengelernt haben, nämlich daß die präpositionale Verbindung durch das Relativwort sa mit dem Nomen verbunden wird.

Aro quotes dozens of examples with various prepositions to support his point. Consider the following examples:

16. assum hubüni sa ïna qdti pahhdri (apud Aro 1963, p. 402) "Was die

h. -Gefäße betrifft, die in den Händen der Töpfer sind, (sende so und so viele Gefäße)."

17. nebrissusa istu saddaqdim ina zumur sassukkim ileqqü (apud Aro 1963, p. 403) "Seinen Hunger, der vom Vorjahr an (gedauert hat), wird man am Leibe des Katasterdirektors strafen."

However, he perceives the construction as a shortened relative clause, i.e.

lacking an element: "Dies ist wohl so zu erklären, daß alleinstehendes Parti¬

zip sehr stark nominalisiert ist, aber in Verbindung mit einem Gen. objecti¬

ves als ein verkürzter Relativsatz aufgefaßt wird." (1963, p. 404)

The only two studies known to us that were reluctant to analyze the pat¬

tern as a sentence are Duval (1881) and Muraoka/Porten (1998). Duval (1881, p. 298, § 317b) maintains that d- with adverbials is an adjective. He compares it to d- with a noun which functions as an adjective (d-ruh 'spir¬

itual', da-bsar 'carnal'). Muraoka/Porten (1998, p. 244, §68c-e) note that a prepositional phrase in Egyptian Aramaic may be introduced by zy. Al¬

though they (inconsistently) translate the examples as sentences, they add that the zy is optional. They further suggest (p. 245, fn. 1006) that a prepo¬

sitional phrase preceded by zy is attributive, while without it, it is adverbial.

However neither of these studies explained the function of the relative pro¬

noun in this pattern.

29In Ga'az, the order of modifiers relative to the noun is variable; nominal modifiers may precede or follow their head noun. If the modern Ethio-Semitic languages are any indication, the trend of movementfor modifiers is to precede their head noun.

The Function of the Relative Pronoun

As was mentioned above, the function of the relative pronoun is related to the issueof this pattern's syntax, namely whether the relative pronoun has a function within the relative clauseor not.

Wright and Fleischer argue that the subject in the nominal clause ex¬

ists Virtually', i.e. is omitted, while the adverbial predicate is formally rep¬

resented. Wertheimer assumes an underlying verb, therefore does not take the relative pronoun to have any formal role within the relative clause.

In contrast to these scholars, many Semitists analyze the relative pronoun as the subject of a nominal clause the predicate of which is an adverbial.

FiTZMYER,Segert and Bau er /Le an de r made this claim regarding Ara¬

maic, where the relative pronoun does not exhibit inflection of any kind. 30 Reckendorf's analysis is the most interesting, since Arabic, unlike most other West-Semitic languages, does show some case inflection. Recken¬

dorf claims that the relative pronoun in Arabic behaves syntactically like the Indo-European pronoun and takes thecase required by the syntax in the relative clause (without this case being formally represented).31 However, in Semitic, as the Arabic evidence clearly shows, the latter statement is never true; whenever case is represented, it is not conditioned by the syntax of the relative clause. Consider the following example, where had the relative pronoun had a function within its clause, it should have been nominative, rather than oblique. The Relative pronoun is in the oblique case, because its antecedent is in the oblique. 32

18. "arind s-saytdnayni (Obi.) lladayni (Obi.) "adalldnd (apud Wright 1896,II, p. 320) "Show us the two demons who led us astray."

In German, for example, the situation is very different, and the case of the rel¬

ative pronoun is determined solely by itsfunction within the relative clause.

19. Der Student (Nom.), dem (Dat.) ich das Buch geborgt habe, kommt morgenzu mir. "The student to whom I have lent the book is coming to me tomorrow."

20. Ich habe dem Ausländer (Dat.), der (Nom.) mit mir studiert hat, eine Einladung geschickt."I sentan invitation to the foreigner who had stud¬

ied with me."

30 This trait makes zi and its later attestations arelative particle, rather than apronoun.

31 See discussion above.

32 Note the following examples from Akkadian, where the relative pronoun has full inflection: SE (Nom.) su (Nom.) ana SE.BAasitu (Kienast: Ga3:4-5) "The barley that I had left over for rations". Here too, had the relative pronoun had afunction within the relative clause, it should have been accusative, not nominative.

The syntax of the relative pronoun in PS is different from the Indo-European (henceforth IE) one. The IE relative pronoun shows case inflection accord™

ing to its function in the embedded clause while its gender-number inflec¬

tion is derived from the antecedent; 33 the Semitic relative pronoun, on the other hand, is not syntactically independent of the main clause, and derives its full inflection (i.e., gender, number, and case) from the function of the preceding noun in the matrix sentence.

In addition, the development of the Germanic relative is usually described as a shift from parataxis to hypotaxis: He wanted the house. That is now his

—> He wanted the house that is now his (Lehmann 1980, pp. 113-114). This is

not the case in Semitic, where the relative developed from a nominal modifier.

Moreover, the IE relative pronoun developed from the demonstrative, while in Semitic the demonstrative and relative arose from the determinative pronoun.

Resumption

The system of resumption in the Semitic languages clearly indicates that, un¬

like IE languages, in Semitic, the relative pronoun has no syntactic function within the relative clause. The relative pronoun only marks the beginning of the clause and carries its agreement with the antecedent in the main clause, while it is the resumptive pronoun that indicates the syntactic function of the antecedent within the relative clause. Thus, when the antecedent is the object of the prepositional phrase, it will be marked as an enclitic pronoun on a preposition 34 and when it is the subject it will be marked in the verb, 35 in the pronominal prefixes or suffixes, as the case may be, and so forth. This can be seen in the following examples:

21. Object of a prep.: (Akkadian) wardumsa ana dlim itti-su alliku ihtaliq (apud Huehnergard 1997, p. 186, § 19.3b) "The servant with whom I went to town has escaped."

22. Object of a noun: (Syriac) hälen d-mekölthön besrä da-hnaynäsä "ïtëh (M ing ana. 1907,' :T50:1) "Those whose nourishment is human flesh."

33 Several linguists emphasized the cumulative nature of the IE relative pronoun. See for example Tesnière (1965, p. 561): "[La pronom relatif] suppose lecumul dun subordinatif (que) avec un pronom qui représente l'antécédent à un certain cas; examples: l'homme dont je n'ai pas de nouvelles 'que (je n'ai pas de nouvelles) de lui ... Cette analyse conduit àentrevoir que le pronom relatif personnel des langues indo-européennes est sans doute le résultat d'une agglutination préhistorique entre un élément translatif invariable et un élément anaphorique variable." For a similar idea see also Ewald (1881, p. 207, fn. 1).

34 II the preposition isan accusative marker (Arabic 3iyyä-, Hebrew 'et etc.) the enclitic pronoun may be placed on the verb in the relative clause, or omitted (see below).

35 Deutsch er (2002, p.90)claims that inthe latter case the marking iszero. This iswrong;

the subject ismarked pronominally in the verb. See Goldenberg 1985 for afull discussion.

23. Subject: (Arabic) 'al-maliku lladi yddilu (apud Wright 1896, ii, 318 A)

"The king who is just."

Only when the antecedent is the direct object, is resumption optional 36: 24. Direct object: (Gs'sz) bd'si za-rd'yewwo (or za-TDyu) (apud Lambdin

1978, p. 106, § 215.1b) "The man whom they saw."

It is obvious, therefore, that neither the relative pronoun nor the antecedent has a function within the relative clause. Therefore, these relative clauses can function as independent sentences in other contexts, as they lack nothing syntactically. Since there can be no sentence which systematically lacks an essential component to complete its nexus, the pattern in question is not to be interpreted as an elliptical relative sentence.

To recapitulate, previous arguments in favor of the relative clause expla¬

nation were based on the assumption that the relative pronoun has a func¬

tion within the relative clause. This assumption has been shown above to be false. Any nexus in Semitic requires a (pro)nominal subject and a predicate.

Verbs, being the exponents of the predicative relation, have an embedded pronominal subject and a lexeme, which is the predicate, fused morphologi¬

cally into one undivided form (Goldenberg 1985, esp. pp. 169-170). Nomi¬

nal sentences in Semitic likewise require an explicit subject and predicate, but in this case they are represented in an analytic clause and therefore their basic structure in Semitic is always (at least) bi-partite. There are no sen¬

tences with only a predicate. 37 Indeed, we cannot find relative clauses which contain only an adjective or a participle, ex. **han-naar *aser yape or waladu lladi kätibun, since these relative clauses are not full sentences, i.e., they do not contain nexus. While sometimes in later Semitic languages we can find predicative participles referring to 3rd person subject with no ex¬

plicit subject 38this is not the case for prepositions and adverbs, which do not show even minimal gender-number inflection.

36 Tsujita (1991) claims that the use of resumptive pronoun when the antecedent isthe direct object islimited in Biblical Hebrew and should not be considered astylistic variant.

According to him, the resumptive pronoun is generally used to avoid syntactic ambiguity (1578) and to render the antecedent more salient (1581). The resumptive pronoun is obliga¬

tory when the antecedent isfirst or second person.

37 In Akkadian, we may find sentences such as niziqtum-ma "There was (only) worry"

(VAB 6 187:12, apud Huehnercard 1986, p. 234) where the sentence seems to consist only ofa predicate. Huehnergard (1986, p. 238, fn. 74) suggests that the function of the particle -ma isa copula, asuggestion first made by von Soden. This was further substan¬

tiated by E. Cohen (2000, p. 225) who argued that -ma can bea copula and that this is an internal Akkadian innovation.

38 Such a behavior of predicative participles and adjectives is an indication of their gradual verbalization. See D. Cohen's definition, section B: "[le verbe] peut constituer

There is no reason why relative clauses should have a systematically dif¬

ferent predicative structure than other sentences in the language. For these reasons, the structure discussed thus far cannot be taken as a relative - or for that matter, any other - sentence.

3. Suggested Solution: Attribution

Since we have established that (a) the pronoun is not a participant in the syn¬

tax of the following clause and that (b) a nominal clause must have explicit subject and predicate, then it is obvious that when a prepositional phrase fol™

lows adeterminative pronoun, it cannot constitute a predicate or an adverb.

In order to reach the right conclusion regarding the structure of this pat¬

tern we should examine the function of the Semitic determinative-relative pronoun. This was done by Goldenberg (1995), who showed that the ad¬

jective, the genitive, and the relative clause are all exponents of the attribu¬

tive relation. The last two can have either a nominal or a pronominal head.

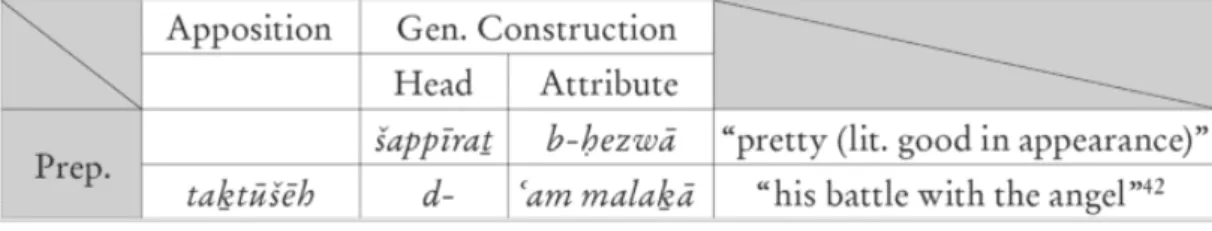

Note Table 1 where a summary of this point in Akkadian is demonstrated. 39 Table1: Attribution

opposition

Gen, Construction Head Attribute

Genitive bit mutis a "her husband's house"

bïtum sa mutis a "her husband's house"

Relative kasap isqulu "the money he paid out"

eUppum sa utebbu "the boat he sank"

Wc concur with previous scholars, such as Goldenberg (following Ungnad), that the original function of the PS *9v pronoun is determinative and that it is a substantival pronoun (Goldenberg 1995, p. 4). 40 In the table, the pro¬

noun is shown to govern what follows it and substantivize it, i.e. "the house, the one of her husband". We argue that the same is true for the pattern in

par lui-même un énoncé assertif fini du fait de sanature d imor phém atique:base verbale + marque personelle représentant le sujet ..." (1975, p. 89). This phenomenon is attested lor Arabic, Aramaic, and Hebrew.

39 The table is taken with adjustments from Goldenberg (1995).

40 In other words, the pronoun is not attributive, i.e. modifying a noun, but rather a substantive which stands in apposition to anoun. This pronoun is independent and may govern another noun (eg.sa-mutïs a "the one of her husband "). Much like the nouns bit and kasap, sa can be the head of a clause (see Table 1).

question. The pronoun substantivizes the prepositional phrase which then stands in apposition to the noun: süzäbä d-men kol meddem "deliverance, the one from everything". This strategy marks the prepositional phrase spe¬

cifically as a nominal modifier. Since the position of prepositional phrases and other adverbs, especially spatial and temporal, is not fixed, any such element may easily be interpreted as ad-verbal, i.e. modifying a verb, unless it is clearly marked as ad-nominal, i.e., modifying a noun.

We would further suggest that both strategies, apposition and genitive, were originally permissible for the prepositional phrase as well: it can be governed by a noun (construct) or stand in apposition to it (preceded by d-). 41 Note the following table, which supplements Table 1 42:

Table 2: Prepositional attribution Apposition Gen. Construction

Head Attribute

Prep» sapplrat b-hezwä "pretty (lit. good in appearance)"

taktusêb d- cam malakd "his battle with the angel" 42 In addition to the three types of nominal attributes mentioned by Golden- berg - adjective, genitive construction, and relative clause - we can postu¬

late a fourth type, an adnominal prepositional phrase. As in the case with genitive construction and relative clause this can be done in two ways: either directly in construct to the modified noun or indirectly in construct to the relative pronoun that stands in apposition to the modified noun.

Unfortunately, at this point this can only be a guess, since with the ex¬

ception of Aramaic and Biblical Hebrew, no Semitic language shows con¬

struct with prepositional phrases. 44 However, since, as we have shown, all

41 The third attributive strategy, modifying a noun directly (like an adjective) is also possible: ma i(länbön l-mesrën (Aph. 27: 13)"their immigration to Egypt".

42 The exact same situation is found in the Neo -Aramaic dialect of Hertevin (Golden- bkkg 1993, p. 297):

;imposition

Gen. (. construction

Head Attribute

rrep.

mtaol p-kölöta "playing with a doll"

m en öx i- d 3ibbu "looking atthem"

43 Eph. in Gen. 7,4-5.

44 There are many examples of construct with prepositions in Hebrew: hare bag-gilbö (a

(2 Sam. 1:21) "mountains in the Gilboa"; ndbï'ë mil-lib bdm (Ez. 13:2) "prophets out of their own idea". See Gesenius (1911, p. 421,§ 130a), Waltke/O'Connor (1990, p. 155a-b) and

languages show the appositional pattern - prepositional phrase following a relative pronoun that stands in apposition to a noun - it is possible to as™

sume a Hebrew-Aramaic-like situation in other languages, which was later lost. If this is so, there is a precise parallel between modification of a noun by a prepositional phrase and by means of genitive construction and relative clause, as a comparison of Table 1 with Table 2 shows.

In a private communication, John Huehnergard offered a different suggestion for the Hebrew-Aramaic situation. According to him, the pat¬

tern is an innovation based on an analogy that was only possible when the absolute and construct state had the same morphological form. Note the following: yôsëb hä- cïr = yôsëb bä- cïr and therefore: yôsbê hä- cïr = yôsbê bä- cïr alongside the original yôsbïm bä- cïr. He also notes that most of the examples in Hebrew are with plural constructs. This development was, of course, not possible in Akkadian, Arabic, and Ethiopie, where the construct of all numbers is distinct from the absolute.

Though this explanation cannot be completely ruled out, we disagree with it. In both Hebrew and Aramaic there are many examples of feminine singu¬

lar nouns that are in construct with a preposition. 45Note the following 46: 25. h amat miy-yäyin (Hos. 7:5) "anger on account of wine". 47

26. ndginat h-Ddwïd (Ps. 61:1) "a poem by David ".

There are also masculine nouns that show a morphological distinction be¬

tween absolute and construct. Consider the following examples 48:

27. he-càrïm mi-qdsë h -matte bdnë Yd hüda (Josh. 15:21) "the cities at the end of (the plot) of the tribe of Judah". 49

28. mik-kol li-banë Yis'raël (Ex. 9:4) "everything the Israelites have". 50 29. mib-bët lä- 3üläm (1 Kg. 7:8) "from within the hall (lit. the house in the

hall)".51"

Jo üon/ Mu raoka (2000, II,p. 470, § 129m-o) for more examples. Gesenius (1911, p. 421,

§130a)notes that most examplesare in elevatedor prophetic style.

45There isonly one possible feminine participle inconstruct: bënpörät <alë cäyin (Gen.

49:22) "a fruitful bough [stretching] overa spring".

46 Seealso constructs of this type with kdtep (Josh. 18:18);makkd (Is. 14:6);mamldkd (Mic.4:8);tô'êbâ (Prov.24:9); puga (Lam. 2:18);mispaha (IChr. 6:55);toh°rd (IChr. 23:28).

In Aramaicthe pattern is very widespread and examples abound.

47 SeealsoPs. 58:5.

48 Secalso mabmad h -k a sp dm(Hos. 9:6) "pleasant places for their money".

49Nouns denoting directions are common in this pattern. The noun sdp on occurs in construct to a preposition inJosh. 8:11; 16:6; 24:30; Judg. 2:9; the noun ydmïn appears in 2Kg. 23:13.Both nouns have construct forms which are distinct from their absolute forms.

50 SeealsoIs.38:16.

51 Seealso Ezek. 1:27

These examples seem to indicate that the phenomenon was more wide spread at some point. Perhaps the fact that absolute and construct masculine nouns in Hebrew and Aramaic are usually homonymous obstructs the original distribution of the pattern.

4. Summary

In this paper we have addressed the pattern *9v- + prepositional clause/ad¬

verb in the Semitic languages. Formerly there were two approaches to ex¬

plain this pattern:

1. The pattern is a verbal relative clause, whose verb was omitted, and only the adverb was left (ex. Wertheimer), or the pattern is a copulative relative clause, whose copula was omitted and only the prepositional predicate was left (ex. Fischer and Wright).

2. The pattern is a nominal relativeclause, where the relative pronoun functions

as a subject and the preposition/adverb as a predicate (ex.Reckendorf).

We have contested these analyses by the following arguments, respectively:

1. Relative sentences do not have different syntax than matrix sentences.

There are no grammatically correct matrix sentences which lack both their subject and their predicate and are construed solely of preposi¬

tional clauses/adverbs. Therefore, we should assume that there are no relative sentences with that syntax either.

2. The relative pronoun is not a part of the relative sentence. If relative pronouns had any syntactical function within the relative clause, we would expect relative sentences with nominal predicates and no pro¬

noun (ex. **3al-waladu lladïjamïlun), yet these do not exist.

We further suggested that the pattern is not a sentence but rather an apposi¬

tion to its antecedent which functions as an ad-nominal attribute. This is in agreement with both the pronoun's original function, i.e. a determinative, and with the syntax of attribution in the attested Semitic languages.

Bibliography

Andersen, F.I. 1970: The Hebrew Ver ble s s Clausein the Pentateuch, Nashville.

Aro, J. 1963:"Präpositionale Verbindungen als Bestimmungen des Nomens im Ak- kadischen." In: Orient alia 32, pp. 395-406.

Bauer, H./P. Leander 1962:Grammatik desBiblisch-Aramäischen, Hildesheim.

Blau, J. 1966-1967: A Grammar of Christian Arabic, Based Mainly on Sout h- Palestinian Texts from the First Millennium. Louvain.

—1995: Grammar of Mediaeval Judaeo-Arabic [Hebrew]. Jerusalem [reprint of the

2nd ed. 1980].

—1999: The Emergence and Linguistic Background of Judaeo-Arabic. Jerusalem.

Bolinger, D. 1967: "Adjectives in English: Attribution and Predication." In: Lin¬

gua 18,pp. 1-34.

Brockelmann, C. 1908-1913: Grundriß der vergleichenden Grammatik der semi¬

tischen Sprachen. Berlin.

— 1938: Syrische Grammatik. Leipzig.

Cantarino, V. 1974-1975: Syntax of Modern Arabic Prose. Bloomington.

Cohen, D. 1975: "Phrase Nominale et verbalisation en sémitique." In: Mélanges linguistiques offerts à Emile Benveniste. Paris, pp. 87-98.

Cohen, E. 2000: "Akkadian -ma in Diachronie Perspective." In: 2A 90, pp. 207-226.

Costaz, L. 1955: Grammaire Syriaque. Beyrouth.

Cow le y, A. 1923: Aramaic Papyri of The Fifth Century B.C. Edited with transla¬

tion and notes. Oxford.

de Sacy, S. 1831: Grammaire arabe. Paris.

Deutscher, G. 2002: "The Akkadian Relative Clauses in Cross- L i n g u i s t ic Per¬

spective." In: ZA 92, pp. 86-105.

Duval, R. 1881: Traité de Grammaire Syriaque. Paris.

Ewald, H. 1881: Syntax of the Hebrew Language of the Old Testament. Tr. J.

Kennedy. Edinburgh.

Fischer, W. 2001: A Grammar of Classical Arabic. Tr. J. Rodcers. New Haven [3rd rev. ed.].

Fit ZM yer, J. A. 1995: The Aramaic Inscriptions of Sefire. Rome.

Fleischer, H.L. 1885-1888: Kleinere Schriften. Leipzig.

Fritz, M. 2003: "Proto-Indo-European Syntax." In: M. M e i er- Brüg g er : Indo- European Linguistics. Berlin, pp. 238-276.

Gai, A. 1978: Adnominal Attributes in Semitic Languages [Hebrew]. Ph.D. Thesis, Jerusalem, The Hebrew University.

Gensler, O. 2002: On Explaining Why Relative Pronouns Lost Case-Marking in Semitic [paper read in Tel Aviv].

— 2005: The Origin of the Definite/Indefinite Distinction in Arabic Relative Clauses [paper read at Harvard NELC - Semitic Philology Workshop].

Gesenius, w/ 1911:Hebrew Grammar. Oxford [2nd Engl. ed.].

G olden berg, G. 1983: "On Syriac Sentence Structure." In: M. Sokoloff (ed.): Ar- ameans, Aramaic and the Aramaic Literary Tradition. Ram atGan, pp. 97-140 [repr. in Goldenberg 1998, pp. 525-568].

—1985: "On Verbal Structure and the Hebrew Verb" [Hebrew]. In: M. Bar-Ash er (ed.): Language studies. I. Jerusalem, pp. 295-348 [repr. and transi, in Golden- berg 1998, pp. 148-196].

—1993: "Otto Jas trow 's Der n euaramäisch e Dialect von H er tevin - A Review Ar¬

ticle." In: JSS 38, pp. 295-308 [repr. in Goldenberg 1998, pp. 630-644].

— 1995: "Attribution in the Semitic Languages." In: Langues Orientales Anciennes:

Philologie et Linguistique 5/6, pp. 1-20 [repr. in Goldenberg 1998, pp. 46-65].

—1998: Studies in Semitic Linguistics. Jerusalem.

Harning, K.E. 1980: The Analytic Genitive in the Modern Arabic Dialects. Göte¬

borg.

Huehnergard, J. 1986: "On verbless clauses in Akkadian." In: ZA 76,pp. 218-249.

— 1997: A Grammar of Akkadian. Winona Lake, Ind.

—2006: "On the Etymology of the Hebrew Relative se. " In: A. Hurvitz/S. Fass- berg (eds.): Biblical Hebrew in Its Northwest Semitic Setting: Typological and

H istorical Perspectives. Jerusalem, pp. 103-125.

Huehnergard, J. /N. Pat-El 2007: "Some Aspects of the Cleft in Semitic Lan¬

guages." In: E. Cohen/T. Bar (eds.): Studies in Semitic and General Linguis¬

tics in Honor of Gideon Goldenberg. Münster, pp. 325-342.

Joüon, P./ T. MuRAOKA2000: A Grammar of Biblical Hebrew. Rome.

Lambdin, T.O. 1978: Introduction to Classical Ethiopie Gd cdz. Atlanta.

Lehmann, W. P. 1980: "The Reconstruction of Non- Simple Sentences in Proto- Indo-European." In: P. Ram at (ed.): Linguistic Reconstruction and Indo- European Syntax. Amsterdam, pp. 113-144.

E. Lipin ski 2001: Semitic Languages. Outline of a Comparative Grammar. Leuven.

Ma RCAis,P. 1956:Le parler arabe de Djidjelli, Nord constantionis, Algérie. Paris.

Mingan a, A. 1907: Sources Syriaques. Leipzig.

Muraoka, T. 1991:"The Biblical Hebrew nominal clause with aprepositional phrase."

In: K.Jongeling et al. (eds.): Studies in Hebrew and Aramaic Syntax Presented toProfessor j. Hoftijser on the Occasion of his Sixty-fifth Birthday. Leiden.

— 1997: Classical Syriac. Wiesbaden.

Muraoka, T./B. Porten 1998: A Grammar of Egyptian Aramaic. Leiden.

Nolo eke, Th. 2001: Compendious Syriac Grammar. Tr. T.A. Crichton, with an appendix, ed. A. Schall, tr. P.T. Daniels. Winona Lake, Ind.

Pennacchietti, F.A. 1968: Studi sui Pronomi Determinativi Semitici. Napoli.

Reckendorf, H. 1895-1898: Syntaktische Verhältnisse des Arabischen. Leiden.

— 1921:Arabische Syntax. Heidelberg.

Rosenthal, F. 1983: A Grammar of Biblical Aramaic. Wiesbaden.

Se Gert, S. 1975: Altaramäische Grammatik. Leipzig.

SIvan, D. 2001: Grammar of the Ugaritic Language. Leiden.

Tenière, L. 1965: Eléments de syntaxe structurale. Paris.

Tonneau, R.-M. 1955: Sancti Ephraem Syri in Genesim etin Exodum Commentarii.

Louvain.

Tropper, J. 2000: Ugaritische Grammatik. Münster.

TsujiTA, K. 1991: "The Retrospective Pronoun in Biblical Hebrew." In: A.S. Kaye (ed.): Semitic Studies in honor of Wolf Leslau on the occasion of his eighty-fifth birthday. II Wiesbaden, pp. 1577-1582.

Waltke, B. K./M. O'Connor 1990: An Introduction to Biblical Hebrew Syntax.

Winona Lake, Ind.

Werth eimer, A. 2001: "The Functions of the Syriac Particle d-" In: Le Muséon 114,pp. 259-289.

— 2005: Special Subordinate Clauses in Syriac: Elliptical Relative Clauses [paper read at NACAL 33 (Philadelphia, PA)].

Wrig ht, W. 1896: A Grammar of the Arabic Language. Cambridge [3rd ed.].