i

WATER, SANITATION AND POVERTY: CBOS ACTIVITIES AND POLICY PLANNING IN NORTHERN REGION, GHANA.

By

Eva Azengapo Akanchalabey

Dissertation Committee:

Univ.-Prof. Dr. Einhard Schmidt-Kallert Univ.-Prof. Dr. Francis Z. L. Bacho Dr. Karin Gaesing

February, 2015

ii

Water, Sanitation and Poverty: CBOs Activities and Policy Planning in Northern Region, Ghana.

By

Eva Azengapo Akanchalabey

A thesis submitted to the PhD Board of the Faculty of Spatial Planning of the TU Dortmund University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor rerum politicarum.

Dissertation Committee:

Univ.-Prof. Dr. Einhard Schmidt-Kallert Univ.-Prof. Dr. Francis Z. L. Bacho Dr. Karin Gaesing

Date of Disputation: January 15, 2015

Published: February, 2015

iii

With unflinching love and profound gratitude, appreciation, and gratefulness To my loving Mother, Son, and the entire Akanchalabey’s family for their support,

motivation, love and encouragement to me during this study

iv

Declaration

I,

Eva Azengapo Akanchalabey, hereby declare that thisacademic work (thesis) has been independently and originally written and produced by me in fulfillment of the requirement for a PhD degree.

Where information, data and/or other earlier material(s) has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated clearly and concisely.

Dortmund, Germany ……….. ……….

Place and Date Name of Candidate: Eva Azengapo Akanchalabey

v

Abstract

The provision of potable water and sanitation (WaS) facilities is of major concern to governments and development actors in Africa and many other developing regions of the world.

This is based on the assumption and recognition that, water and sanitation are sine qua non to good health and poverty alleviation, especially in rural and agrarian communities. Adverse climatic changes with the attendant reduction in the quantity and quality of water supplies, however, require concerted efforts to ensure provision and access to safe water and good sanitation. The need for improved WaS facilities cannot therefore be underestimated. The access to these facilities is no longer a luxury but a necessity.

This study addresses issues of accessibility to WaS facilities mainly by women and girls in underserved rural communities in Ghana. The study delved into the contribution of local stakeholders (CBOs) in WaS. To investigate access to WaS services by rural dwellers and the contribution of local government structures and CBOs in the provision of these facilities in Northern Region, Ghana, a mixed methods strategy was employed. Using a mix of observation, interviews and questionnaires in a cross sectional survey in six (6) rural communities, the study found that CBOs are established to complement the activities of international organizations and donors. This is done through different partnership arrangements, mostly on short term basis.

CBOs depend on financial resources of international and donors whereas donors rely on human resources of CBOs to implement projects.

The study also revealed that, besides the construction of physical facilities, CBOs are actively involved in providing services such as animation and capacity building in communities.

This is dominant in the provision of sanitation facilities where there are attempts to reorient and emphasize change in attitudes through trigger effect methodologies.

Access to alternative sources of water (besides boreholes) remains a major challenge while rain harvesting and storage is not highly patronized because of the nature of roofing materials of houses. Furthermore, water facilities are highly patronized and better managed than sanitation facilities owned and managed by individual households. This is however, in contrast with the norm of the Ghanaian society that manages individual properties or facilities efficiently to that of community facilities. Besides, there are challenges with sustainability of facilities both WaS. Women are less pragmatic than men, in managing these facilities. This conforms to low women involvement in managerial positions in Ghana. On the other hand, there are no significant differences in the status of poverty of households in communities with access to WaS as against those with less access to these facilities.

Based on these and other findings, I recommend institutional restructuring whereby CBOs are integrated into District Assembly Systems through their representatives. International partners and donors should engage in medium to long term partnership arrangements with CBOs for easy access to professional advice as well as capacity building to develop long term plans for projects.

Finally, women who are recognized as effective financial managers should be encouraged

through mass media publicity and affirmative actions. This will encourage their compatriots to

be active in the management of these facilities to ensure sustainability. Furthermore, spot fines

especially for poor sanitation practices should be introduced to deter recalcitrant citizens and

ensure compliance with improved sanitation practices in the region. This would generate income

for local authorities (DAs) to undertake other infrastructural projects. Rural electrification should

be extended alongside WaS to effectively reduce poverty in rural communities.

vi Abstract:

Versorgung mit sauberem Wasser und Entsorgung von Abwasser gehören zu den wichtigsten Aufgaben von Regierungen und Nichtregierungsorganisationen. Die große Bedeutung dieser Aufgabe ergibt sich daraus, dass das Vorhandensein von Wasser und Kanalisation als unabdingbare Voraussetzungen für die Erhaltung der Gesundheit und die Minderung der Armut gelten. Klimaveränderungen und dadurch verursachte quantitative und qualitative Verschlechterungen der Wasserversorgung erfordern gemeinsame Anstrengungen, um eine funktionierende Ver- und Entsorgung von Wasser zu gewährleisten. In den hier untersuchten ländlichen Gebieten in der ghanaischen Savanne wären sie eine Voraussetzung für die Verbesserung elementarer Lebensbedingungen, die jedoch häufig nicht ausreichend vorhanden ist. Die vorliegende empirische Studie konzentriert sich auf Fragen des Vorhandenseins und der Erreichbarkeit entsprechender Anlagen und Einrichtungen, vor allem für Frauen und Kinder - basierend auf der Annahme, dass vor allem sie es sind, die sich um Beschaffung von Trinkwasser und Entsorgung von Schmutzwasser kümmern. Trotz der zentralen Bedeutung, die der Wasserversorgung und Kanalisation zugeschrieben wird, haben bislang nicht alle dazu beitragenden Komponenten die ihnen gebührende Aufmerksamkeit erfahren. Während der Einfluss der lokalen Stakeholder (vor allem internationale (Spender)Organisationen) vergleichsweise gut erforscht ist, ist noch wenig bekannt, welche Rolle selbstorganisierte Bewohnergruppen, die sich autonom in den Gemeinden gebildet haben und sich für diese Infrastrukturproblematik engagieren, in diesem Zusammenhang spielen und wie ihr Engagement genutzt werden kann.

Das Zusammenwirken von staatlichen Organisationen und lokalen Bewohnergruppen wird in dieser Studie erstmals genauer untersucht. Um ihren Einfluss auf die Entwicklung der sanitären Infrastruktur zu analysieren, wurden zwei Fallstudien/Fallbeispiele ausgewählt, um zunächst die Arbeitsweise dieser lokalen Bewohnergruppen zu verstehen. Mit einem Methodenmix aus Beobachtung, strukturierten und Tiefeninterviews und standardisierten Fragebögen konnte schließlich in einem Querschnittssurvey aus sechs ländlichen Gemeinden gezeigt werden, dass diese Art von lokalen Gruppen als Ergänzung zur Arbeit internationaler Organisationen und ihrer Spendenbeiträge gebildet wurden. Wie festgestellt werden konnte, geschieht dies meist auf der Basis kurzzeitiger Arrangements von Partnerschaften zwischen ihnen. Ein weiteres Ergebnis der Studie war, dass – unabhängig vom Bau von Anlagen – diese Gruppen auch anregend, aufklärend und anleitend wirken, vor allem indem sie Methoden verwenden, die auf eine Einstellungsänderung zielen. Eine grundlegende Herausforderung ist zudem die durch Erschließung alternativer Wasserquellen (neben Bohrlöchern), da z. B. die Anlage von Zisternen aufgrund der ungeeigneten Bedachungen der Häuser nahezu ausscheidet.

Zwei Befunde sind von besonderem Interesse: erstens besteht ein grosser Unterschied in der

Nachhaltigkeit, mit der öffentliche und private Anlagen betrieben werden. Je bedeutsamer die

Rolle von Frauen beim Management öffentlicher Anlagen ist, desto nachhaltiger werden diese

betrieben. Zweitens konnten statistisch signifikante Unterschiede zwischen der Nutzbarkeit

vii

sanitärer Infrastruktur und der Armutsverringerung gemäß der Nullhypothese nicht nachgewiesen werden.

Das bedeutet, dass die Nutzbarkeit sanitärer Infrastruktur allein noch nichts aussagt über daraus entstehende wirtschaftliche Effekte. Vielmehr zeigte sich, dass bereits vor oder bei der Inanspruchnahme mancher Anlagen für die ihnen zugedachten Zwecke eine Barriere zu sehen ist, deren Überwindung eine dringliche kommunalpolitische Aufgabe darstellt. Meine Empfehlung geht deshalb dahin, die Zusammenarbeit der lokalen Gruppen mit den „District Assemblies“ besser zu institutionalisieren und sie stärker als bisher einzubinden. Auf der nationalen Ebene sollten sich die Medien die Aufsicht und Betreuung der kommunalen Gruppen zur Aufgabe machen. Internationale Partner sollten ihre Zusammenarbeit mit den lokalen Gruppen auf mittel- und langfristige Zeiträume ausrichten um den Zugang zu professioneller Beratung auf Dauer sicher zu stellen und langfristige Projekte planen zu können.

Schließlich sollten Frauen, die sich in finanziellen Fragen als verlässilche und solide „Manager“

erwiesen haben, z. B. über die Massenmedien ermutigt werden, verantwortliche Positionen auch

in diesem Bereich einzunehmen. Weiterhin sollten Bußgelder für den unangemessenen Umgang

mit der Versorgungsinfrastruktur eingeführt werden, um den langfristigen Erhalt der Anlagen zu

sichern. Damit ließen sich Einnahmen für die District Assemblies zum Aufbau anderer

Infrastrukturprojekte erzielen, z. B. den Ausbau der Elektrifizierung entlang wichtiger

Entwicklungsachsen, weil sich diese als wesentlich bedeutsamer für die Verringerung der Armut

in ländlichen Gemeinden gezeigt hat.

viii

Acknowledgements

This thesis received attention and contributions from many individuals and institutions that need commendation. My immediate appreciation is to God for the overwhelming mercies, grace, blessings and wisdom received from him to work on this thesis.

I cannot show appreciation to any other individual or institution without the mentioning of the

Katholischer Akademischer Ausländer Dienst (KAAD). Studying in Germany would notbe possible without sponsorship. KAAD gave me the financial support to pursue this task, which is much appreciated by the entire Akanchalabey’s family. I will forever be grateful for the difference KAAD has contributed to my life. Within KAAD, I would like to give special thanks to Dr. Marko Kuhn (Head of Africa Department) and Frau Simon Saure (Secretary at the Africa Department) for their warm affections, support, unflinching love and encouragements during my studies.

To the academic environment, Prof. Dr. Einhard Schmidt-Kallert of the University of Dortmund cannot be forgotten. You are a great supervisor to my work and my professional upbringing.You were the only supervisor to my work. You gave me the academic, professional guidance and counseling. You also encouraged and motivated me throughout my studies especially during the last part. This relationship should continue after this thesis work. Within the same environment, I would like to express my profound gratitude to Dr. Karin Gaesing who was my examiner. I thank also Prof. Francis Bacho. To Dr. Anna Weber and all my colleagues of our doctoral peer review programme especially Dr. Emmanual Tamanja, Teresa Sprague, Dr. Ahmed El-Atrash, Dr. Genet Alem, and Dr. Mais Aljafari who supported me in one way or the other. I am most grateful for the support and the regular peer review sessions on my work. I have also enjoyed all the other social interactions from you all.

During field work, a lot of individuals and institutions assisted with data and documents.

It is not possible to mention all of you in this report however; I appreciated the contributions you all made. It is a great pleasure to express my profound gratitude to Mr. Imoro Sayibu, Charles Nachinaab of NewEnergy and Nashiru Bawa of CLIP for providing me with data any time I approached you. I would also like to mention friends such as Benjamin Akumanue and Stephen Ajuwaik for their immense support during my field work. I appreciate the efforts and sacrifices you all made. To Central Gonja District, Yendi and Savelugu Nanton Municipalities, I say a very big thank you for your understanding and assistance during challenging moments; yet, you extended a helping hand to me.

Last but not the least; I would like to thank my immediate family in Germany and Ghana for their support and contributions. Auntie Pauline Akankyalabey and Wolfgang Wittmann proof read most of my scripts and made valuable corrections and contributions. I would like to emphatically thank my loving mother who assisted in taking good and moral care of my son, Conrad Awontiirim Atenyong Jones while I was pursing my studies in Germany. Conrad also comported himself and deserved to be commended. Others are Dr. Barbara Meier and family, Dr.

Ulrike Blanc and family, Karolina Becker and family and Fr. Philippe Harm. I would like to also thank Stephen Adaawon and Elias Kusaana who were also pursuing their Ph.D at Zentrum für Entwicklungsforschung (Centre for Development Research), University of Bonn and who supported and shared materials with me.

Your support is not in vain. There would not be another time, when I would allow you to

endure loneliness, separation and isolation from a motherly care. For those I have not been able

to mention individually, your support, contributions and genuine love remains in my heart and is

appreciated all the days of my life.

ix

Table of Contents

Declaration... iv

Abstract ... v

Acknowledgements ... viii

Table of Contents ... ix

List of Figures ... xiv

List of Tables ... xvi

Abbreviations ... xvii

Chapter 1: General Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background to the Study ... 2

1.2 The Role of Local Actors ... 5

1.3 Why a Study into WaS ... 5

1.4 The Problem Statement ... 6

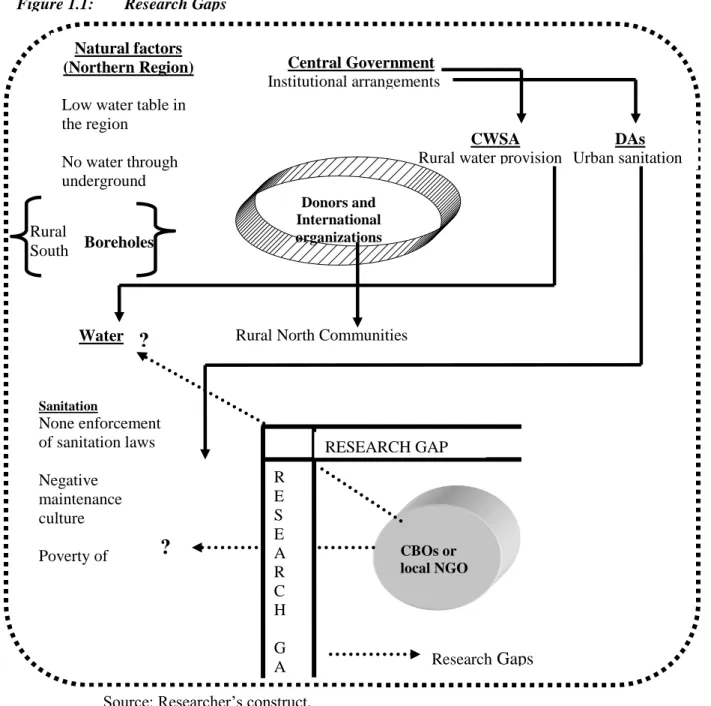

1.5 Research Gaps ... 7

1.6 Research Objectives ... 10

1.7 Relevance of the Study ... 10

1.8 Structure of the Report ... 11

Chapter 2: Conceptual Issues: “Poverty and Development” ... 15

2.1 Challenging Nature of Poverty ... 16

2.2 The Issue of Poverty ... 17

2.3 “Poverty” What is it? ... 18

2.4 Who are the Poor? ... 20

2.5 Poverty in Geographical Locations ... 23

2.6 Possible Reasons for Poverty ... 24

2.7 Economic Perspective of Poverty ... 26

2.8 Measure of Poverty ... 26

2.8.1 The Poverty Line ... 26

2.8.2 Lorenz Curve and Gini Index ... 27

2.9 The New Lens of Poverty ... 27

2.10 Development Trajectories ... 28

2.10.1 An Economic Perspective of Development ... 31

2.11 Forms of Development ... 32

2.11.1 High Economic Development ... 32

2.11.2 Middle Economic Development ... 32

2.11.3 Low Economic Development ... 33

2.12 Necessitating Factors Accounting for Development ... 33

2.13 WaS and Economic Growth Linkages ... 34

2.14 Poverty, Development and the Environment Nexus ... 34

2.15 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) ... 37

2.16 Reducing Poverty in a World of Rich Resources ... 39

2.16.1 Global Level ... 40

2.17 Institutions Championing the Developmental Agenda ... 42

2.17.1 The State ... 42

2.17.2 Civil Society Organizations ... 43

2.18 What Difference have these Organizations Made? ... 44

2.19 Conclusion ... 45

Chapter 3: Northern Region and Water and Sanitation Development ... 47

3.1 Historical Background to Northern Region (NR), Ghana ... 47

3.2 Regional Division and Development ... 48

x

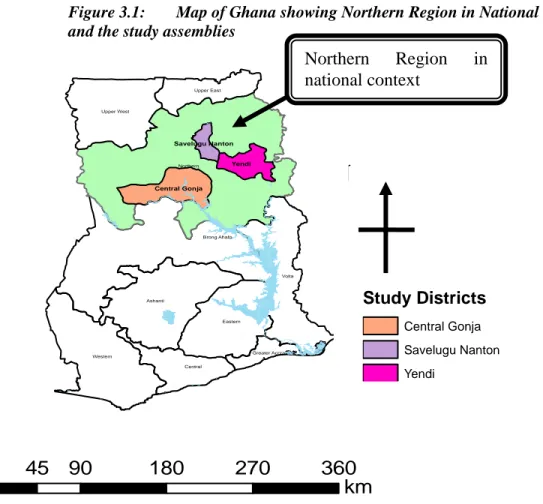

3.3 Northern Region in Geographical Retrospect ... 49

3.3.1 Geographical Location ... 49

3.3.2 Geophysical Features of the Region ... 50

3.4 Demographic Features ... 54

3.5 The Local Economy ... 55

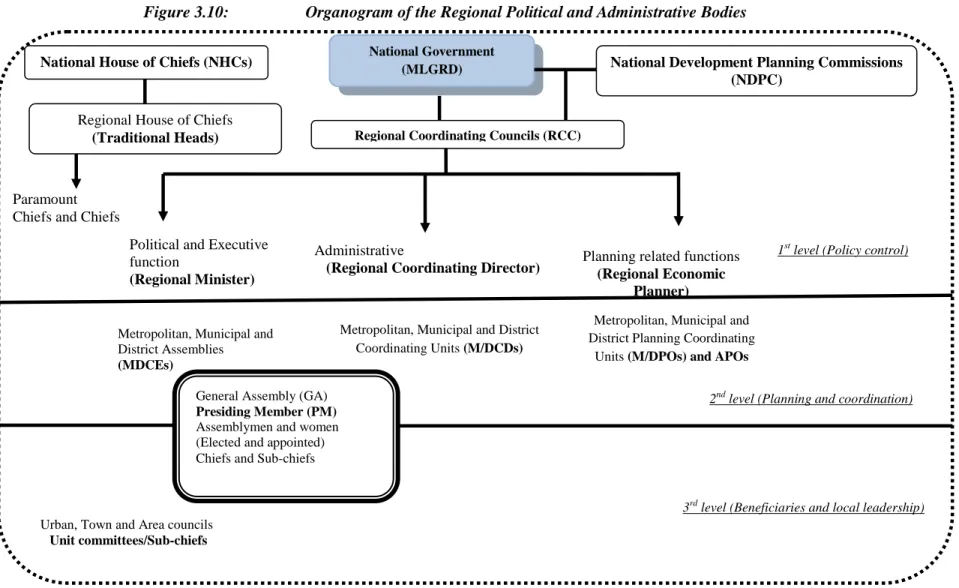

3.6 Northern Region Administrative and Political Structure ... 56

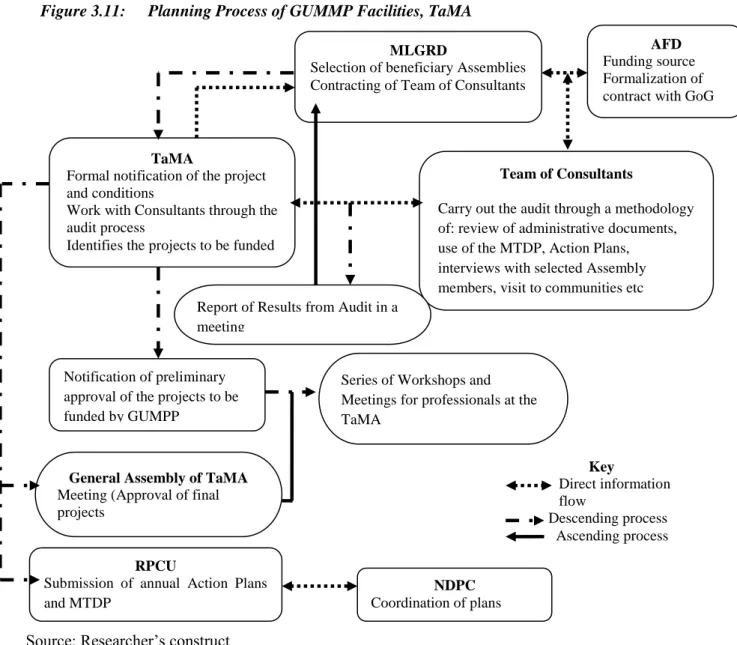

3.6.1 Practical Demonstration of how the Organogram Works ... 59

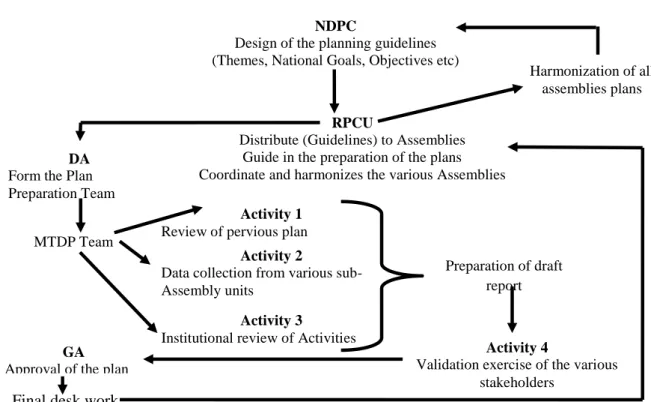

3.6.2 Comparing and Contrasting the two Planning Processes... 63

3.6.3 Discussion of the Planning and Implementation Gaps between the two Processes ... 64

3.7 Operations of other Civil Society Organizations in the Region ... 64

3.8 Summary of First Section ... 67

3.9 Infrastructure Development ... 68

3.9.1 Infrastructure Development in Northern Region ... 68

3.9.2 Urban Water Service Provider ... 69

3.9.3 Water Infrastructure in Urban Communities ... 70

3.9.4 Urban Water Services ... 72

3.9.5 Urban Sanitation Infrastructure ... 72

3.10 Policy Transformation in WaS Delivery in Ghana ... 72

3.11 Policies Discourse in WaS in Ghana... 74

3.11.1 Elements across Policies ... 80

3.11.2 Community Water and Sanitation Agency (CWSA) ... 82

3.11.3 Major Institutional Changes in Rural Water and Sanitation Delivery ... 83

3.12 Conclusion ... 87

Chapter 4:CBOs in Rural Poverty Reduction through WaS Services Provision: A Conceptual Framework ... 89

4.1 The Community Concept ... 89

4.2 Defining the Rural Community ... 93

4.3 Community Development (CD) ... 94

4.4 Community Based Organizations (CBOs) ... 96

4.4.1 Categorization of CBOs ... 98

4.5 Theoretical Discourse of Community Development, Rural Infrastructure Provision and Rural Development ... 99

4.6 Region Defined ... 99

4.6.1 Rural Development (RD): Overview ... 101

4.6.2 Regional Rural Development Strategy ... 102

4.6.3 The Emergency of Basic Human Needs ... 103

4.6.4 Decentralization ... 104

4.6.5 The Rural Environment and the Adaptation of these Strategies ... 104

4.7 Community Based Organizations in WaS Infrastructure Provision: The Conceptual Framework ... 104

4.8 An Analytical Framework Linking WaS and Poverty ... 109

4.9 Assessing the Role of CBOs on Rural WaS Provision ... 111

4.9.1 Lobbying... 111

4.9.2 Negotiations ... 112

4.9.3 Partnerships ... 112

4.9.4 Networking ... 112

4.9.5 Collaborations ... 113

4.9.6 Monitoring and Evaluation ... 114

4.10 The Main Research Issues ... 114

4.11 Research Questions ... 115

4.11.1 Hypothesis to be Investigated ... 115

4.12 Conclusion ... 116

xi

Chapter 5: The Research Design ... 117

5.1 The Nature of Social Science Research (SSR) ... 117

5.2 Researcher’s Methodology Standpoint ... 118

5.3 Research Design ... 119

5.3.1 Justification for Mixed Methods Research (MMR) ... 119

5.3.2 Components of Mixed Method Research ... 120

5.4 The Case Study Strategy and its Tenets ... 121

5.5 The Scope of the Study ... 123

5.5.1 Conceptual and Contextual Scope ... 123

5.5.2 Geographical Scope ... 124

5.6 Population ... 124

5.6.1 Sampling Procedure under the Qualitative Design ... 125

5.7 Qualitative Data Sources and Methods of Data Collection ... 127

5.7.1 Primary Data ... 127

5.7.2 Methods of Qualitative Data Collection ... 128

5.8 Survey Research ... 130

5.8.1 Quantitative Methods ... 131

5.8.2 Sampling Procedures under Quantitative Methods ... 131

5.8.3 Summary of the Sampling Plan ... 133

5.8.2 Quantitative Data Collection Processes ... 134

5.8.3 Other Data Sources ... 135

5.9 Data Reliability and Validity ... 136

5.10 Ethical Considerations and Confidentiality ... 138

5.11 The Entire Research Process ... 140

5.12 Data Processing ... 143

5.12.1 Computer Software Programmes ... 143

5.13 Data Management ... 144

5.14 Analytical Process ... 145

5.15 Concurrent Triangulation Analysis ... 146

5.16 Conclusion and Limitation of the Study ... 147

Chapter 6: Structural Arrangements of CBOs in the WaS Sector and their Linkages with Other Actors ... 149

6.1 Rural Settlement Pattern and Basic Needs Provision ... 149

6.2 Legislative Instruments Guiding the Operations of CBOs ... 150

6.2.1 Formation Guidelines ... 151

6.3 CBOs Structure in Ghana... 152

6.4 Case 1: NewEnergy... 153

6.4.1 Organizational Structure of NewEnergy ... 153

6.4.2 Operational areas ... 154

6.4.3 Choice of Operational Areas ... 155

6.4.4 WASH under NewEnergy ... 156

6.4.5 Components of WASH under NewEnergy ... 156

6.5 Administrative and the Decision Making Processes in NewEnergy: How are the Processes Done and Who Does What? ... 157

6.5.1 Funding Arrangements and Processes ... 162

6.5.2 Mechanisms used to Source Funding for Project Implementation ... 164

6.5.3 Partners ... 167

6.5.4 Stakeholder Consultations ... 168

6.6 Case 2: Community Livelihood Improvement Programme (CLIP) ... 170

6.6.1 General Organizational Structure of CLIP ... 171

6.6.2 Operational Areas ... 172

xii

6.6.3 CLIP in the Water and Sanitation Sector ... 173

6.6.4 Decision Making and Project Management Arrangements in CLIP ... 174

6.6.5 Partners and Partnership Arrangements in CLIP ... 177

6.6.6 Reasons for Partnership Arrangements ... 179

6.6.7 The Advantages and Disadvantages of Partnership Arrangements ... 181

6.7 Commonalities among the Cases ... 183

6.8 Networking Analysis ... 186

6.9 Summary and Discussion of Emerging Issues ... 190

Chapter 7: Basic Needs Provision in Rural Communities: The Case of WaS Infrastructural Facilities and Services by CBOs ... 191

7.1 Potable Water Facilities ... 191

7.2 Water Facilities ... 192

7.3 Water Systems Explained ... 194

7.3.1 Small Town Water Systems (STWSs) ... 194

7.3.2 Limited Reticulated Water Systems (LRWS) ... 195

7.3.3 Rain harvesting ... 196

7.4 Sanitation Systems ... 197

7.4.1 Sanitary Facilities ... 197

7.4.2 Facility Usage ... 198

7.4.3 Materials used in Constructing Sanitary Facilities ... 199

7.4.4 Facility Maintenance ... 201

7.4.5 Reasons for Poor Sanitation... 202

7.4.7 Patterns of Defecation ... 204

7.4.8 Sanitation Markets ... 205

7.5 Levels of Facility Provision ... 205

7.6 Case 1: Water facilities and Services Delivery under NewEnergy ... 206

7.6.1 The case of Central Gonja District and the Savelugu Nanton Municipality ... 206

7.6.2 Services in WaS ... 207

7.7 Case 2: CLIP and its Water and Sanitation Facilities and Services ... 212

7.7.1 The Case of the Yendi Municipality ... 212

7.7.2 CLTS Policy ... 213

7.7.3 The Safe Zone Flag Methodology (SZFM) ... 213

7.8 Functionality of WaS Facilities and Services ... 217

7.9 Sustainability Arrangements ... 221

7.10 Summary and Conclusion ... 227

Chapter 8: Access to Potable Water and Sanitation Facilities, Services and Rural Poverty Reduction in the Northern Region ... 229

8.1 WaS and Poverty Perceptions ... 229

8.2 WaS and Poverty Reduction Nexus ... 234

8.3. Access to Water Facilities and Health Awareness ... 236

8.4 Access to Sanitation Facilities and Health Awareness ... 241

8.5 Mixed Reactions to Poverty Reduction ... 243

8.6 Criteria for Assessing WaS and Poverty Levels in Communities ... 245

8.7 Communities and Socio-Economic Indicators Comparison ... 246

8.8 Discussions and Conclusion ... 255

Chapter 9: Theoretical Lens and the Realities in WaS Provision in Northern Region . 259 9.1 Realities in Water Provision and Supply ... 259

9.2 Veracity in Sanitation Concerns ... 260

9.3 Factors Affecting Theory in WaS Planning and Implementation ... 261

9.3.1 Assessment of Occupational Realities ... 261

9.3.2 Technicalities in Construction of Facilities (Sanitary Facilities) ... 262

9.3.3 Geographical Locations ... 263

xiii

9.3.4 Facilities as Disincentives... 263

9.4 Measures to Realities ... 264

9.4.1 Localized Planning and Local Needs Achievements ... 264

9.4.2 CLTS in Sanitation Management ... 265

9.4.3 Community Operation and Maintenance (COM) in Water Development ... 265

9.4.4 Water Disaggregation Use ... 265

9.4.5 WaS Planning ... 266

9.5 Reflections and Conclusions ... 267

Chapter 10: Lessons, Recommendations and Conclusion ... 269

10.1 Major Lessons ... 269

10.2 Summaries of findings ... 270

10.2.1 CBOs ... 270

10.2.2 Water ... 271

10.2.3 Sanitation ... 272

10.2.4 Poverty Reduction ... 273

10.3 Recommendations ... 274

10.3.1 Water Facilities Improvement ... 274

10.3.2 Sanitation Development ... 275

10.3.3 CBOs ... 276

10.3.4 Poverty Reduction ... 277

10.3.5 Recommended Action Plan ... 277

10.4 Revised Conceptual Framework ... 280

10.5 Recommended Areas for Future Studies ... 282

10.6 Conclusion ... 283

Bibliography: ... 284

Appendices ... 303

Appendix 1: List of Key Informants ... 303

Appendix 2: Observation Guide ... 307

Appendix 3: Household survey Instrument ... 308

Appendix 4: List of Research Assistants and Translators ... 312

Appendix 5a: Interview Guide (CBOs) ... 312

Appendix 5b: Interview Guide (DAs, DWSTLs) ... 313

Appendix 5c: Interview Guide (CWSA) ... 313

Appendix 5d: Discussion Guide ... 314

Appendix 5e: FGD Attendees ... 315

Appendix 6: Questionnaire for National and International NGOs in Water and Sanitation Development ... 315

Appendix 7: List of NGOs Operating in the WaS Sector in NR, Ghana ... 319

Appendix 8a: Districts in Northern Region ... 321

Appendix 8b: Sampling Procedure of the Districts ... 322

Appendix 8c: Questionnaire for Selection of CBOs ... 322

Appendix 9a: Chi Square and Tables Values for Sanitation and Health Hazards ... 323

Appendix 9b: Contingency Coefficient for Access to Sanitation Facilities and Health Hazards from Table 8.2 ... 323

Appendix 9c: Calculated (²) Value as against (²) Table Values ... 323

Appendix 9d: Motor Bike Usage ... 323

Appendix 10: Community Scoring Sheet under SZFM Competition ... 324 Appendix 11: Transcribed Group Interview on WaS and Poverty Nexus (Kusawgu Kootito) 326

xiv

List of Figures

Figure 1.1: Research Gaps ... 9

Figure 1.2: Structure of the Thesis... 12

Figure 2.1: Poverty, Development and the Environment Nexus ... 36

Figure 3.1: Map of Ghana showing Northern Region in National Context and the study assemblies ... 50

Figure 3.3: Eroded Land in Wamalie in Tamale ... 51

Figure 3.4: Women, Children and Animals Competing for Water in Kusawgu ... 52

Figure 3.5: Vegetation of Wambong during the Rainy Season ... 52

Figure 3.6: An Isolated Baoba Tree in Mion in the Sang District ... 53

Figure 3.7: Flooding of the White Volta, Buipe in 2010 ... 54

Figure 3.8: Art and Craft Shop at TCC ... 55

Figure 3.9: Aboabu Market in Tamale... 56

Figure 3.10: Organogram of the Regional Political and Administrative Bodies ... 58

Figure 3.11: Planning Process of GUMMP Facilities, TaMA ... 61

Figure 3.12: Planning Process of MTDP (2010-14) ... 63

Figure 3.13: Regional Structure of GWC ... 69

Figure 3.14: Water Treatment Plant at Dalum, Northern Region ... 71

Figure 3.15: Water Systems in Northern Region ... 71

Figure 4.1: Web of Communities ... 92

Figure 4.2: Categorization of CBOs ... 99

Figure 4.3: Conventional WaS Supply and Provision Dynamics ... 105

Figure 4.4: Proposed Conceptual Framework ... 107

Figure 4.5: Analytical Framework Linking WaS and Poverty ... 110

Figure 5.1: The Research Design ... 121

Figure 5.2: Sampling Procedure for the Communities ... 127

Figure 5.3: Interview with the Assemblyman of Wambong ... 132

Figure 5.4: Summary of Sampling Plan... 134

Figure 5.5: Comments on Field Tools during World Café in Dortmund ... 137

Figure 5.6: The Research Process ... 141

Figure 5.7: An Analytical Framework for Triangulation ... 145

Figure 6.1: Formation Linkages between CBOs and Governmental Institutions ... 151

Figure 6.2: Organizational Structure of NewEnergy ... 154

Figure 6.3: Decision Making and Taking Process in the Ghana School Feeding Enhancement Project ... 158

Figure 6.4: Planning and Implementation of IP: Second Urban Environmental Sanitation Project II... 161

Figure 6.5: Funding Arrangements, Processes, Flows and Reporting ... 163

Figure 6.6: Partners and Partnership Structure NewEnergy ... 168

Figure 6.7: Stakeholder Consultation in Project Management ... 169

Figure 6.8: Organizational Structure of CLIP ... 172

Figure 6.9: Operational Themes of CLIPS ... 173

Figure 6.10: Decision Making and Project Management Arrangements in CLIP ... 175

Figure 6.11: Financial Flows of CLIP ... 178

Figure 6.12: Comparative Analysis of Cases in Water and Sanitation in Ghana ... 184

Figure 6.13: Networking Analysis ... 188

xv

Figure 7.1: Source of Water for Household Use in the Region ... 191

Figure 7.2: A Dugout Well Observed in Wambong ... 192

Figure 7.3: Rain Harvesting Containers in Kusawgu ... 193

Figure 7.4: STWS in Buipe... 194

Figure 7.5: A Borehole Facility in Wambong in the Yendi Municipality ... 196

Figure 7.6: A Rain Harvesting Tank for a Teacher’s Quarters in Wambong, Yendi Municipality ... 196

Figure 7.7: Sanitation Facility Usage ... 198

Figure 7.8: A Mud Pit Latrine ... 199

Figure 7.9: A Zanamat Pit Latrine ... 199

Figure 7.10: Pit Latrine Used as a Well ... 200

Figure 7.11: Hand Washing Container on a Tree in Wambong ... 201

Figure 7.12: Collapsed Sanitary Facility in Damdo ... 204

Figure 7.13: Abandoned Sanitary Facility in Damdo ... 204

Figure 7.14: Contingency Defecation ... 204

Figure 7.15: The Water and Sanitation Committees Linkages in the Study Region ... 209

Figure 7.16: SZFM Implementation Processes... 214

Figure 7.17: SZFM Demonstration ... 216

Figure 8.1: Major Water and Sanitation Related Diseases in the Three Districts ... 232

Figure 8.2: WaS and Poverty Reduction Nexus ... 235

Figure 8.3: A Compound Housing Unit in Kusawgu ... 246

Figure 8.4a: Building Materials Used in the Housing Units ... 247

Figure 8.4b: Building Materials Used in the Housing Units ... 248

Figure 8.5a: Energy for Household ... 249

Figure 8.6: Energy for Household Usage (lighting... 250

Figure 8.7a: Household Assets in Communities with Maximum Access to WaS Services .. 252

Figure 8.7b: Household Assets in Communities with Less Access to WaS Services ... 253

Figure 8.8a: Land and Livestock Holdings of Households ... 254

Figure 8.8b: Land and Livestock Holdings of Households ... 255

Figure 9.1: Water from Different Sources in the Household ... 266

Figure 10.1: Revised Conceptual Framework after the Study ... 281

xvi

List of Tables

Table 2.1: Global Poverty Indicators... 21

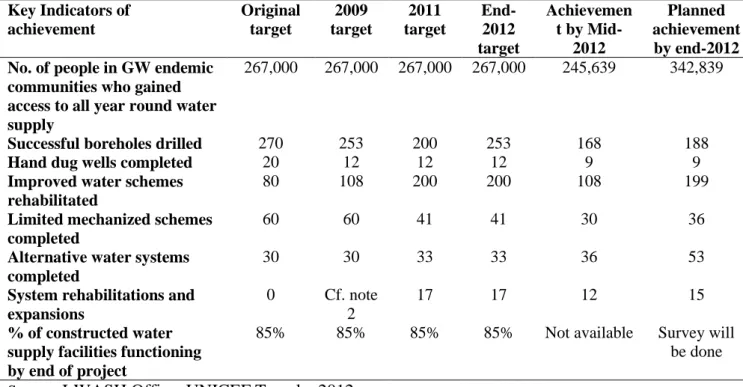

Table 3.1: Sustainable Safe Drinking Water by June 2012 against Planned Targets... 66

Table 3.2: Basic Changes in Water and Sanitation Policy in Ghana... 73

Table 3.3: WaS Policy before Independence to Date ... 79

Table 3.4: Regional Coverage Statistics: Potable Water (Community Based Water Systems) ... 86

Table 4.1: Roles Played by CBOs in Infrastructure Provision ... 113

Table 5.1: Details of Interviews Conducted in the Field ... 128

Table 5.2: Communities and their Households Statistics in the 3 Assemblies ... 132

Table 5.3: Selecting the Households in Communities ... 133

Table 5.4: Research Objectives, Type of Data, Sources of Data and Methods/ and Tools Employed ... 139

Table 5.6: Second Data Collected ... 144

Table 5.7: Summary of Second Data Collected ... 144

Table 6.1: Reasons for Partnership Arrangements in Project Implementation ... 180

Table 7.1: Water Sources and Facilities ... 192

Table 7.2: Households and Sanitary Facilities ... 198

Table 7.3: Households Maintenance of Sanitary Facilities ... 202

Table 7.4: Reasons for Poor Sanitation ... 203

Table 7.5: Level of Facility Provision ... 206

Table 7.6: Water and Sanitation Facilities Functionality Levels ... 218

Table 7.7: Water Variables Measured ... 219

Table 7.8: Community Needs According to Priority... 221

Table 7.9: Service Providers in WASH ... 222

Table 7.10: District Assemblies in WASH... 225

Table 8.1: Relationship between Access to Water Facilities and Illnesses Awareness ... 237

Table 8.2: Calculated (²) Value as against (²) Table Values ... 238

Table 8.3: Relationship Between Access to Sanitation Facilities and Illnesses Awareness ... 241

Table 8.4: Communities and Their Use of Mobile Telephoning... 251

Table 8.5: Possession of Sanitary Facilities and Other Household Assets ... 254

Table 10.1: Recommended Action Plan ... 278

xvii

Abbreviations

AAP Annual Action Plans

AFD L’Agency francaise de development

AGOA Africa Growth and Opportunities Act

AMCOW African Ministers Council on Water

ANEW Africa Network of Civil Society Organizations

AVRL Acqua Vitens Rand Limited

BHNs Basic Human Needs

BNDT Basic Needs Development Theory

BoD Board of Directors

BM Board Members

BMZ German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and

Development

BOT build, operate and transfer

BRICS Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa

BW Bretton Woods

C Contingency Coefficient

CARE Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere

CBD Central Business District

CBOs Community Based Organizations

CCFC Christian Children Fund of Canada

CD Coordinating Director

CDD Community-based Driven Development

CE Chief Executive

CEO Chief Executive Officer

CHPS Community –based Health Planning and Services

CIDA Canadian International Development Authority

CLIP Community Livelihood Improvement Programme

CLTS Community-Led Total Sanitation

CONIWAS Coalition of NGOs in Water and Sanitation

CRS Catholic Relief Services

CS Civil Servants

CSOs Civil Society Organizations

CSPIP Civil Service Performance Improvement Programme

CSM Case Study Method

CSV Community Surveillance Volunteers

CWSA Community Water and Sanitation Agency

DAs District Assemblies

DANIDA Danish Development Agency

DCD Department of Community Development

DDL Det Danske Ledelsesbarometer

DPDT District Project Delivery Team

DPs Development Plans

xviii

DSW Department of Social Welfare

DWSTs District Water and Sanitation Teams

DWSTLs District Water and Sanitation Team Leaders

DWTP Dalum Water Treatment Plant

EC Executive Council

ECG Electricity Company of Ghana

EHOs Environmental Health Officers

EHSD Environmental Health and Sanitation Department

EHU Environmental Health Unit

EPA Environmental Protection Agency

ESA External Support Agency

ESW Economic Sector Work

FDOs Fertilizer Desk Officers

FGDs Focus Group Discussions

FMECD Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and

Development

FMPs Facility Management Plans

FWAN Fresh Water Action Network

GA General Assembly

GD Grassroots Development

GDDA Ghana Danish Development Association

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GFG Ghana Friendship Group

GHS Ghana Health Services

GI-WASH Ghana Integrated-Water Sanitation and Hygiene

GIZ Gesellschaft fur Internationale Zusammenarbeit

GNI Gross National Income

GNP Gross National Product

GoG Government of Ghana

GPHC Ghana Population and Housing Census

GSFP(EP) Ghana School Feeding Programme Enhancement Project

GSS Ghana Statistical Service

GTUS Ghana Time-Use Survey

GUMPP Ghana Urban Management Pilot Project

GWCL Ghana Water Company Limited

GWEP Guinea Worm Eradication Programme

GWSC Ghana Water and Sewage Cooperation

HDR Human Development Report

HICP Highly Indebted Poor Country

ICT Information Communication Technology

IIED International Institute for Environment and Development

IDA International Development Authority

IEWRM Integrated Environment and Water Resource Management

IFPRI International Food Policy Research Institute

IGF Internal Generated Funds

IHDP Integrated Human Development Programme

xix

IMF International Monetary Fund

INNGOs International Non-governmental Organizations

IPs Invited Projects

I-WASH Integrated Water Sanitation and Hygiene

KfW Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau

KVIP Kumasi Ventilated Improved Pit

LEAP Livelihood Empowerment against Poverty

LED Local Economic Development

LLEDPs Local Led Economic Development Plans

LI Legislative Instruments

LRWSs Limited Reticulation Water Systems

MASLOC Micro Finance and Small Loans Center

M/MDCEs Metropolitan/Municipal District Chief Executives

M/MDCDs Metropolitan/Municipal District Coordinating Directors

MDGs Millennium Development Goals

MoE Ministry of Energy

MoH Ministry of Health

MLGRD Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development

MoU Memorandum of Understanding

M/MPCUs Metropolitan/Municipal Planning Coordinating Units

MMRD Mixed Methods Research Design

MTEF Medium Term Expenditure Framework

MTDP Medium Term Development Plan

MWRWH Ministry of Water Resources Works and Housing

NAFCO National Buffer Stock Company

NCWSP National Community Water and Sanitation Programme

NCF National Economic Forum

NDPA National Development Planning Authorities

NESP National Environmental Sanitation Policy

NFEP Non-Formal Education Programmes

NGOs Non-Governmental Organizations

NIG National Income Growth

NIRP National Institutional Renewal Programme

NNGOs National Non-Governmental Organizations

NNP Net National Product

NORRIP Northern Region Rural Integrated Project

NPA New Policy Agenda

NRC Navrongo Research Center

NT Northern Territories

NWP National Water Policy

NWSP National Water and Sanitation Programme

OECD Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

OD Open Defecation

ODF Open Defecation Free

ODI Oversea Development Institute

OIC Opportunities and Investment Center

xx

OPD Out Patient Department

PAMSCAD Programme of Action to Mitigate the Social Cost of Adjustment

PC Programme Coordinator

PHCR Population and Housing Census Report

PM Presiding Member

PMT Project Management Team

PNDC Provisional National Defense Council

POCC Potential Opportunities Constraints Challenges

POs Partner Organizations

PPA Programme Partnership Agreements

PPPs Public Private Partnerships

PPT Plan Preparation Team

PRA Participatory Rural Appraisal

PSP Private Sector Participation

PURC Public Utilities Regulatory Commission

RA Regional Assemblies

RGD Registrar General Department

RCC Regional Coordinating Council

RCD Regional Coordinating Director

RD Rural Development

REGSEC Regional Security Committee

REPO Regional Economic Planning Officer

REDTs Regional Economic Development Theories

RDTs Regional Development Theories

RM Regional Minister

RPA Rural Participatory Appraisal

RRDS Regional Rural Development Strategy

RRDTs Regional Rural Development Theories

RWD Rural Water Department

RWS Rural Water Supply

RWaS Rural Water and Sanitation

SADA Savannah Accelerated Development Authority

SADI Savannah Accelerated Development Initiative

SAI Security Authorities and Institutions

SAP Structural Adjustment Programmes

SCs Small Communities

SDGs Sustainable Development Goals

SEND Social Enterprise Development Foundation

SLA Sustainable Livelihood Approach

SMA Sector Ministries and Agencies

SMART Specific Measurable Achievable Realistic Time-bound

SMT Senior Management Team

SNMA Savelugu Nanton Municipal Assembly

SNV Stichtung Nederlandse Vrijwilligers (Netherlands

Development Organization)

xxi

ST Small Towns

STWSs Small Town Water Systems

SWR Savannah Woodland Region

SZFM Safe Zone Flag Methodology

TaMA Tamale Metropolitan Assembly

TCC Tamale Cultural Center

UER Upper East Region

UESP II Urban Environmental Sanitation Project II

UN United Nations

UNGA United Nations General Assembly

UNDP United Nation Development Programme

UNICEF United Nation International Children Education Fund

UR Upper Region

UWR Upper West Region

VRA Volta River Authority

WA WaterAid

WaS Water and Sanitation

WASH Water, Sanitation and Hygiene

WASHPs Water Sanitation and Hygiene Plans

WATSANs Water and Sanitation Committees

WASHNET Water and Sanitation Network in NG

WB World Bank

WBR World Bank Report

WDBs Water Development Boards

WDR World Development Report

WC Water Closet

WCED World Commission on Environment Development

WFP World Food Programme

WHT Water Harvesting Tank

WRC Water Resources Commission

WRI Water Research Institute

WSDBs Water and Sanitation Development Boards

WSRP Water Sector Restructuring Project

WSTLs Water and Sanitation Team Leaders

WW II World War II

WWC World Water Council

1

Chapter 1: General Introduction

The provision of potable Water and Sanitation (WaS) infrastructural facilities and services to meet the needs of the world’s growing population date back to the 1970s. For instance, in 1977, the UN convened a conference in Mar del Plata to deliberate and take initiatives in potable water provision. This conference was aimed at making clean drinking water accessible to communities.

The UN Water Conference at Mar del Plata declared 1981-1990 as the first “International Decade for Clean Drinking Water” (UN, 1977). This was the first of its kind with subsequent follow up conferences and declarations. Again, in November, 2002 the Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (the Committee) advocated for the right to water (Salman, 2012: 44). According to (Salman, 2012) cited the General Comment No. 15, paragraph 2:

“The human right to water entitles everyone to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physical, accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic uses. An adequate amount of safe water is necessary to prevent death from dehydration, to reduce the risk of water related diseases and to provide for consumption, cooking, personal and domestic hygienic requirements”.

Based on this argument, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) adopted Resolution 64/292 in 2010 declaring the right to safe and clean drinking water. Water and sanitation are human right that is essential for the full enjoyment of life and all human rights (Salman, 2012). Attempts by the global community to address access to WaS especially, for the poor and vulnerable are enormous and cannot be overemphasize. The “World Water Week” held annually in Stockholm brings together leaders and experts from the world’s scientific, business, governmental and civic communities to exchange views, experiences and shape joint solutions to global water challenges. Today, March, 22

ndannually is devoted to world water day, a symbolization to sensitize stakeholders to see the need to make drinking water accessible to everyone.

This global picture accorded Ghana the opportunity to also develop its water supply systems. A major land mark was when Community Water and Sanitation Act (Act 564) was enacted in 1998 establishing Community Water and Sanitation Agency (CWSA). The aim of Act 564 is to ensure that potable water supply and sanitation services are available and accessible to all citizens especially in rural communities.

Despite the major changes and numerous activities in the sector, most communities (rural) still lack access to potable WaS facilities. For instance, it was reported that; “more than 90% of households are within 30 minutes of their source of drinking water compared to 82.1%

recorded in 1997 and poor services meaning “safe sanitation is available to only 55% households and these facilities are even scarcer among the rural poor with only 9.2% of their households having access to these facilities” (Ghana Statistical Service, 2010).

There are still variations to access and use of water globally. From the estimation

according to (Salman, 2012), an average American uses 90 gallons of water a day while an

average European uses 53 gallons a day. A sub-Saharan African uses only 5 gallons of water a

day. The five gallons used by the sub-Saharan African is ten times the amount of water used by

an average European and almost twenty times that of an American. Even in some instance, this

argument does not hold, simply because of inaccessibility of water. On sanitation, over 2.6

2

billion people have no access to sanitation facilities globally, while 1.5 million children under age 5 die annually of waterborne diseases (Salman, 2012). These statistics are striking and attracts investigation into the “whys”, “what” and “how” of the problem.

Consequently, the statistics has attracted more stakeholders into the WaS sector more especially in Northern Region. For example, there are activities of international, national and local organizations and donors in this sector. Their activities attract attention and questions relating to; why there is still lack of access to WaS facilities in the midst of numerous activities in the sector.

More so, it was in the past that most rural people saw water as a natural resource that was provided freely by nature (Bacho, 2001) and probably did not factor management and preservation mechanisms to its use. Today, such communities are aware through media and stakeholder’s activities the need to manage their facilities for sustainability. However, there are still communities that cannot gain access to these services. This has resulted in the drinking of water from unapproved sources.

For instance, health workers in

Central Gonja district (CGD), highlighted reasons why Northern Region accounted for slightly more than half of the 229 guinea worm reported cases in the country during the first six months of 2009.There was evidence of the use of water from unapproved sources such as

dams and ponds hiking the spread and prevalence of guinea worminfestation. For example, persons who already had the infestation and had open sores, enter these water bodies and release the worm larvae for many more to get, once they drink from these infested sources (www.who.int/bulletin/volumes).

On the part of sanitation, some of the reasons accounting for poor sanitation in these areas from personal observations are the neglect as well as the failure to recognize sanitation as a matter of human dignity by local authorities. While there are by-laws on sanitation, their enforcement is ineffective resulting in the construction of houses without sanitary facilities.

Poverty on one hand, hinder individuals in these communities from constructing these facilities.

If government and many other stakeholders are actively involved in the sector with sector reforms, donor participation and implementation of programmes, why then is the situation still like this? It will be interesting, therefore, to find out what has changed with these interventions.

Has access to WaS facilities and services improved in rural communities in Northern Region or has the situation remained the same? If the situation is the same, what is/are the factors hindering improvement in the sector? This chapter presents a general background to the study, the problem statement and the relevance of the study. The chapter concludes with an outline of the entire study.

1.1 Background to the Study

The welfare implications of safe WaS cannot be overstated. Infectious diarrhea and other serious waterborne illnesses are leading causes of general ill health and mortality, especially infant mortality and malnutrition. Their impacts extend beyond health to economic in the form of lost work days and school absenteeism especially among the girl children. It is estimated that meeting the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) for access to safe water would produce an economic benefit of US $ 3.1 billion (2000) in Africa, a gain realized by a combination of time savings and health benefits (Banerjee and Morella, 2011).

Saravanan and Gondhalekar (2013) cited in UNDP (2006) argued that WaS are among the most powerful preventive medicines available to governments to reduce infectious diseases.

Investment in this area is to killer diseases like diarrhoea just as what immunization is to

3

measles- a life-saver (Saravanan and Gondhalekar, 2013: 6). The benefit of improved WaS is overwhelming because of the economic benefits of health, productivity and high income.

While acknowledging that there are gains in investing in WaS, (Bacho, 2001) stated that, education, health, potable water and sanitation particularly critical for Africa’s development receives less investment as a result of the increasing debt burden. The situation has further worsened as a result of the over reliance on primary agriculture production, low technological advancement, hiking population growth, climatic change, a blurred democratic governance environment and more recently corruption. These factors, among others, have resulted in fruitless attempts to improve many sectors of the economy including WaS in order to reduce poverty especially in the northern part of Ghana.

Consequently, the problem is exacerbated because of low population growth in these areas coupled with rural housing pattern where housing units are dispersed and scattered. This makes provision of WaS facilities capital intensive looking at the facility cost and the population to a facility.

Irrespective of this picture, Ghana has committed herself throughout the years to the provision of WaS facilities especially in rural communities. Governmental development policy on WaS date back to British Gold Coast. During British rule in the Gold Coast, the Public Works Department (PWD) was created to provide both rural and urban water supplies (Smith, 1969;

Bacho, 2001). Furthermore, in 1937, the Geological Survey Department (GSD) was again established (Smith, 1969). The mission of GSD was to investigate possible new water sources, advise public medical officers, political administrators and personnel on proper well digging and maintenance procedures, improve sanitary conditions and prevent further pollution of surface water sources. In 1944, a separate department of Rural Water Supply (RWS) was established solely to address rural water supply through hand dug wells, reservoirs as well as train and supervise local water administrators (Smith, 1969). To further make the sector vibrant and resilient, in 1977, the Ghana Water and Sewerage Corporation (GWSC) was established and charged with the responsibility of providing, distributing, conserving, and managing water supply development and installation, as well as coordinating all activities related to water supply in the country (Gyau-Boakye, 2001). These developments were an attempt to make improved water accessible nationwide.

Aside these, in 1998, Community Water and Sanitation policy was formulated and Community Water and Sanitation Agency established. The main policy thrust was that beneficiaries of potable water supply and sanitation were now responsible for the management of the facilities. This paradigm shift resulted in a significant improvement in access to potable WaS.

For instance, water supply coverage was 56 percent (52 percent for rural/small town and 61 percent for urban areas). Sanitation coverage was 35 percent. In terms of rural urban differences, 32 percent of the rural communities and small towns and 40 percent urban areas were covered (GSS. 2006). Nine years later, in 2010, 69.6% of the population in the entire region had access to improved water and about 72.6% still had no access to sanitary (toilet) facilities (PHCR, 2013:

107-110). This is woefully unexpected looking at the policy transformation and reforms as well as the stakeholder involvement in the WaS sector. Improvement of the sector for accessibility to services however, has a strong link to many more sectors.

Literature explains the water and gender linkages. This is basically the case in the study

region because; from personal observation after ten years working experience in the region,

about 80% of women are breadwinners. Women work on their farms to provide food for the

family. After the farm work, women are responsible to sell in market centers in order to make

4

additional income to pay school fees of their children, pay hospital bills and other social and household expenses. In addition to this, it is the same women and girls who return to the house to provide water for all domestic chores (Baden et al. 1994).

Not only is WaS linked to gender but to many more sectors. WaS development is linked to education, health, agriculture and tourism. The unavailability of water in a community takes children out of school to search and hunt for water. Government’s policy of ensuring that all children of school going age are in school may not be achieved if availability and accessibility to potable water is not achieved. When communities drink from infected water sources, they are infested with water borne diseases. This could result in low agricultural productivity, the back- bone of the rural economy in the region. A community afflicted with water related diseases will also experience a reduction in the number of tourists in the community. This would again reduce foreign exchange earnings that accrue from such activities. While admitting without doubt that these arguments stand, there is no evidence from research to conclude that communities that have developed their WaS sectors have drastically reduced poverty.

Although, Edwin Chadwick published a general report on the “Sanitary Condition of the

Laboring Population of Great Britain” in 1842 to stimulate sanitary awakening and socialreforms; this report by Chadwick described the prevalence of disease among the laboring people, showing that the poor exhibited a preponderance of disease and disability compared to more affluent individuals. The conclusion of Chadwick’s report was that the unsanitary environment caused the poor health of working people. Disease was attributed to miasma and bad odors.

Epidemic diseases such as typhus, typhoid, and cholera were attributed to filth, stagnant pools of water, rotten animals, vegetables, and garbage. This is evident in the linkages of environmental sanitation and health. It could then be argued that a good health care system controls unimproved WaS hazards directly and that health should rather influence poverty reduction to that of WaS.

Nonetheless, WaS development, education attainment, quality health care, high agriculture productivity, tourism among others have economic effects of reducing poverty. These linkages depend to a large extent on the angle one perceives and the policies implemented.

(Sachs, 2005: 50) posits that “a good plan of action starts with a good differential diagnosis of the specific factors that have shaped the economic conditions of a nation”.

This could probably be the reason why WaS development is among the targets at the global front, where, the (UN, 2000) challenged governments of member countries to ensure the attainment of key goals affecting poverty and human dignity. The global effort has increased international stakeholder involvement and community participation because of the realization that governments are no more in the position to provide these facilities and services for all as a

“free gift”.

While acknowledging the countries preparedness to make improved water accessible to all, it is worth mentioning that the Ghanaian situation has been aggravated by economic policies such as Structural Adjustment and Privatization strategies pronounced by international monetary organizations for government in the 1980s. In the heat of implementing these donor driven policies, attempts have been or are being made to privatize water supply systems giving rise to issues of ability to pay by vulnerable groups, conflicts between the profit and social motives by private investors and long term sustainability.

As these questions are being asked, it is observed that WaS development in rural

communities are relegated mostly to donors and international organizations. One thing that is

clear is that there is the realization that collaborative partnership between the state, private sector

5

and self-organized civil society groups is yet another experimental institutional arrangement that provides for enhanced access to potable water (Bacho, 2001).

1.2 The Role of Local Actors

The challenges in the WaS sector notwithstanding, there is local attention in WaS with local organizations involvement. While this is the case, there is little literature about their activities.

There is abundant literature on the role of local actors in development, NGOs and their involvement in development (Riddell and Robinson, 1995; Abegunde, 2009; Esman and Upholt, 1984; Bralton, 1990 and Willis, 2010). For instance, these "bottom-up" organizations are more effective in addressing local needs than larger charitable organizations (Riddell and Robinson, 1995). According to (Adeyemo, 2002 cited in Abegunde, 2009) their coming together creates conditions which broaden the base of self governance and diffusion of power through a wider circle of the population. Is this the case also with the local organizations in WaS in the Northern Region? Why have international organizations taken all the attention from these local organizations? The main focus in the sector rest on donors and international organizations whereas these local organizations are probably the ones working to address local needs as posited by (Riddell and Robinson, 1995).

On one hand, decentralized planning and implementation where Districts Assemblies (DAs) plan and implement programmes is the current policy regarding local development nationwide. Working at the Metropolitan Assembly in the Planning Coordinating Unit, it was observed that while the assemblies in conjunction with some local organizations plan and implement activities together, some are hardly involved in the process. This has created an imbalanced and duplication of limited resources and at times breads local conflicts between governmental units, communities and these local organizations.

It is against this backdrop that this study is envisaged to understand how these local organizations operate in WaS in the region. This would unearth their contribution(s) and enhance policy planning.

1.3 Why a Study into WaS

Scientific research is a “process of trying to gain a better understanding of the complexities of human experience and, in some genres of research, to take actions based on that understanding”

(Marshall and Rossman, 1999: 21). Through systematic and sometimes collaborative strategies,