IHS Economics Series Working Paper 106

October 2001

Status Seeking in the Small Open Economy

Walter H. Fisher

Franz X. Hof

Impressum Author(s):

Walter H. Fisher, Franz X. Hof Title:

Status Seeking in the Small Open Economy ISSN: Unspecified

2001 Institut für Höhere Studien - Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS) Josefstädter Straße 39, A-1080 Wien

E-Mail: o ce@ihs.ac.atffi Web: ww w .ihs.ac. a t

All IHS Working Papers are available online: http://irihs. ihs. ac.at/view/ihs_series/

This paper is available for download without charge at:

https://irihs.ihs.ac.at/id/eprint/1377/

Status Seeking in the Small Open Economy

Walter H. Fisher, Franz X. Hof

106

Reihe Ökonomie

Economics Series

106 Reihe Ökonomie Economics Series

Status Seeking in the Small Open Economy

Walter H. Fisher, Franz X. Hof October 2001

Institut für Höhere Studien (IHS), Wien

Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna

Contact:

Walter H. Fisher

Department of Economics and Finance Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS) Stumpergasse 56, A –1060 Vienna, Austria (: +43/1/599 91-253

fax: +43/1/599-91-163 email: fisher@ihs.ac.at

Franz X. Hof Institute of Economics

Vienna University of Technology Karlsplatz 13, A –1040 Vienna, Austria fax: +43-1-58801-17599

(: +43-1-58801-17566 email: fxhof@pop.tuwien.ac.at

Founded in 1963 by two prominent Austrians livi ng in exile – the sociologist Paul F. Lazarsfeld and the economist Oskar Morgenstern – with the financial support from the Ford Foundation, the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education and the City of Vienna, the Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS) is the first institution for postgraduate education and research in economics and the social sciences in Austria. The Economics Series presents research done at the Department of Economics and Finance and aims to share “work in progress” in a timely way before formal publication. As usual, authors bear full responsibility for the content of their contributions.

Das Institut für Höhere Studien (IHS) wurde im Jahr 1963 von zwei prominenten Exilösterreichern – dem Soziologen Paul F. Lazarsfeld und dem Ökonomen Oskar Morgenstern – mit Hilfe der Ford- Stiftung, des Österreichischen Bundesministeriums für Unterricht und der Stadt Wien gegründet und ist somit die erste nachuniversitäre Lehr- und Forschungsstätte für die Sozial- und Wirtschafts - wissenschaften in Österreich. Die Reihe Ökonomie bietet Einblick in die Forschungsarbeit der Abteilung für Ökonomie und Finanzwirtschaft und verfolgt das Ziel, abteilungsinterne Diskussionsbeiträge einer breiteren fachinternen Öffentlichkeit zugänglich zu machen. Die inhaltliche Verantwortung für die veröffentlichten Beiträge liegt bei den Autoren und Autorinnen.

Abstract

In our modified version of the small open economy Ramsey model, we assume that agents have preferences over consumption and status which, in turn, is determined by relative wealth. This extension potentially eliminates the standard model's counterfactual result that an impatient country over time mortgages all of its capital and labor income. We show that the steady-state values of net assets and consumption, the speed of convergence and, in particular, the direction of adjustment during the transition depend crucially upon the degree of status consciousness. The latter also influences the economy's response to macro- economic shocks.

Keywords

Status seeking, relative wealth, open economy dynamics

JEL Classifications

E21, F41

Comments

The authors are grateful to Farhad Rassekh and Ted Palivos for their constructive comments. Fisher also acknowledges the generous financial support of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank (OeNB)

Contents

1 Introduction 1

2 The Model and Intertemporal Equilibrium 5

2.1 General Specification of Preferences ...5 2.2 Parameterized Model ... 15

3 The Role of Status in Macroeconomic Adjustment 17

3.1 Fiscal Shocks ... 18 3.2 Productivity Shocks ... 20

4 Conclusions 21

References 22

Figures 27

5 Mathematical Appendix A-1

Anindividual'sutilityisusuallystatedintermsoftheabsolutelevelsofeconomicvariables,

suchasconsumptionofgoodsandservices,leisure,wealth,etc.Thisstandardspecication

isintuitivelyappealingandadequatetostudymanyeconomicproblems.Thereisevidence,

some of which is provided by Easterlin (1974, 1995), Clark and Oswald (1996), Oswald

(1997), and Frank (1997), to indicate,however, that an individual's economic well-being

dependscruciallyonhisrelativeposition,orstatus,insociety.Theideathatindividualsare

motivatedbystatusconsiderations isa veryoldone ineconomicsand canbetraced back

to thinkerssuchasDavidHume(1978) andThorstein Veblen (1899). After World WarII

interestinthisidea andits potentialpolicyimplicationswasmaintainedbyauthors such

as Duesenberry (1949), Scitovsky (1976), Hirsch (1976), Boskin and Sheshinski (1978),

Layard (1980), and Frank (1985a,b). In thelast decade, there are an increasing number

of researchers who study status preference in a dynamic macroeconomic or endogenous

growth context. In general, there are two alternative ways inwhichstatus is modelledin

macroeconomicsettings.TheapproachadoptedbyGal(1994), Persson(1995), Harbaugh

(1996),Rauscher(1997b),Grossmann(1998),LjungqvistandUhlig(2000),andFisherand

Hof(2000)speciesthatstatusderivesfromrelativeconsumption.Incontrast,Corneoand

Jeanne (1997), Rauscher (1997a), Futagami and Shibata (1998), Fisher(2001), and Hof

and Wirl(2001)considerthatstatusarisesfromrelativewealth.

1

While alltheseauthors

modeltheroleofstatuspreference inaclosedeconomycontext,we willintroducerelative

wealth into an otherwise standard small open economy Ramsey model. We believe this

is an important extensionof thislineof research dueto the increasing integration of the

worldeconomyandthegreaterroleplayedbyinternationalassetsinwealthaccumulation.

Ourwork is,inaddition,related to therecent Spiritof Capitalismliterature,whichis

exempliedbyauthorssuchasCole,Mailath,andPostlewaite(1992),Zou(1994,1998)and

BakshiandChen(1996),who seekto explaingrowth,savings,andassetpricingbehavior.

This research, based on the ideas of Max Weber (1958), views wealth accumulation as

1

Itissometimesarguedthatbecauseitiseasierto\see"anotherperson'slevelofconsumptioncompared

tohiscorrespondingstockofassets,thattherelativeconsumptionapproachisamoreappropriatewayto

modelstatuspreferencethantherelativewealthapproach.With,however,employeestock-optionsplans,

amongotherformsofcompensation,becomingmorewidespread,itmaybecomeeasiertoobserverelative

wealththanwaspreviouslythecase.

goods that are regarded as \prizes" by society at large. As stressed by Cole, Mailath,

andPostlewaite(1992),utilityfunctionsthatincludevariablessuchasrelativewealthcan

thenbeinterpretedasreduced-formversionsofpreferencesover\deep"variablesinwhich

dierent socialorganizationscan lead todierent reduced-form preferences.

A further motivation for our approach is to oer an alternative solution to a long-

standing issue in open economy macroeconomics: the fact that the representative agent

model of the small open economy|under the assumption of perfect capital mobility|

doesnothavea\sensible"steady-stateequilibriumifthedomesticrateoftimepreference

diersfrom theworld interestrate. Forinstance,iftheexogenous rate oftime preference

of domestic residents exceeds the exogenous world interest rate, then agents eventually

mortgage all of theircapital and laborincome. In contrast, ifthe economy is \more pa-

tient" than all others,it acquiresover timethe wealth of all other countries and,indeed,

ceasesto be asmallopeneconomy. 2

Inorder,then,forthesmallopen economytoattain

an interior equilibrium with a positive level of consumption, equality must be imposed

betweenthe domesticrate oftime preferenceand the world interestrate. Thiscondition,

however, rules out the possibilityof transitional dynamics, since it also xes a particu-

lar stock of physical capital or assets. Turnovsky (1997) discusses several ways in which

the standard small open economy Ramsey model can be extended to yield an interior

long-run equilibrium and sensible transitional dynamics.

3

One approach that has been

extensivelyused,[see,forinstance,Brock(1988),SenandTurnovsky(1989a,1989b,1990),

and Frenkel, Razin, and Yuen (1996)], is to maintain the assumption that the domestic

rate of time preference equals the world interest rate, but to additionally incorporate a

convexinstallationcostfunctionfordomesticphysicalinvestment.Thismodicationyields

saddlepathdynamics forphysicalcapitaland its shadowvalue,but|dueto thespecied

equality between the rate of time preference and the world interest rate|consumption

equals its steady-state value for all time t, as in the standard model. If, however, labor

supply is endogenously determined, then consumption does display saddlepath behavior

2

SeeBarroandSala-i-Martin(1995),chapter3for adiscussionofthesecounterfactualcases.

3

SeeTurnovsky(1997),chapters2and3.Healsopointsoutthatthepotentiallyunpleasantfeaturesof

thestandardmodeldonotoccur intheusualoverlappinggenerations frameworkoritsBlanchard(1985)

variantinwhichpeople,ordynasties,dieorandomly.AnextensiveanalysisofBlanchard'smodelisgiven

inBarroandSala-i-Martin(1995),chapter3.

who point out the diÆculty in reconciling covariance properties of aggregate, postwar

U.S. data with those of macroeconomic models that incorporate plausible values of the

adjustment cost parameter.

4

Another, though more controversial, approach to generate

sensible, long-run equilibriaand saddlepathdynamics in the small open economy model

is to specify that representative agents possess Uzawa (1968){type, time-dependent, en-

dogenous rates of time preference. This was the method used by Obstfeld (1982) in his

work studying open economy dynamics.Authors such as Blanchard and Fischer (1989),

Barro and Sala-i-Martin (1995) and Turnovsky (1997) nd this formulation intuitively

unappealing, however, because a necessary condition in the innite horizon context to

generatesaddlepointdynamicsistospecifythattherateoftimepreference increaseswith

thelevelof consumption.Obstfeld(1990), drawingonthework ofEpstein (1987), among

others, oersadefense ofthisapproach andpointsoutitsusefulnessinrelaxingthemore

usualassumption oftime-additivepreferences, which isalso restrictive.

Twoadditional,and related,approachesto addressingthisissueareeithertoincorpo-

rate costs ofholding foreignbondsor to specifyan upward-slopingsupply curve of debt.

Both approaches attempt to model, in a certainty equivalence framework, the macroe-

conomic implications of imperfect substitutability between domestic and foreign assets.

The rst approach was taken by Turnovsky (1985), while the second has been adopted

in Bhandari, Haque, and Turnovsky (1990). Usingthese specications, interior solutions

areobtainedwithoutimposingequalitybetweentherateoftimepreference andtheworld

interestrate.Becauseassetstocks willthenadjustslowlyaccording to internationalarbi-

trage, economies with these specications exhibit saddlepathtransitional dynamics.One

issue thatarises in thesetwo cases isthe factthat transitionaldynamics can degenerate,

dependingon the macroeconomic shock inquestion.

5

In addition,it can be argued that

itisbetter tomodeltheimplicationsofinternationalcapitalmarketimperfections, which

depend, at least inpart, on the risk characteristics of domestic and foreign assets, in an

explicitlystochastic setting.

Our model will oer an alternative way to generate interior long-run equilibriawith

4

ThispointismadebyKydlandandPrescott(1982).

5

Fisher(1995)andFisherandTerrell(2000)show,however,thattheupward-slopingdebtspecication

isusefulincalculatingtheimplicationsofworldinterestratedisturbances.

These properties arise dueto the assumption that, inaddition to own consumption,the

instantaneousutilityof agents is a functionof status, which dependson relative wealth.

Contrary to the existing literature, we will employ a specication of the status function

that does not rule out|by denition|steady states with negative values of nonhuman

wealth.Inordertoconcentrateontheinuenceofstatuspreference,wewillabstractfrom

population growth, technological progress, depreciation and installation costs of physi-

cal capital, and the heterogeneity of agents. Using an innite-horizon, perfect-foresight

framework, we will derive a symmetric equilibrium in which identical agents make the

same choices.Our formulationofstatus preferencewillresultina modiedversionofthe

Euler equation. Its crucial feature is that the exogenous world interest rate is replaced

byan endogenous, \eective" domesticrate of returnthat depends also on consumption

and net assets. Weak assumptions with respect to preferences willyield saddlepoint dy-

namics. We will also incorporate a public sector in order to examine how the eects of

(balanced-budget)scalpolicyareinuencedbystatuspreferences.Inadditiontochanges

ingovernment expenditure,we willconsidertotal factor productivityshocks.

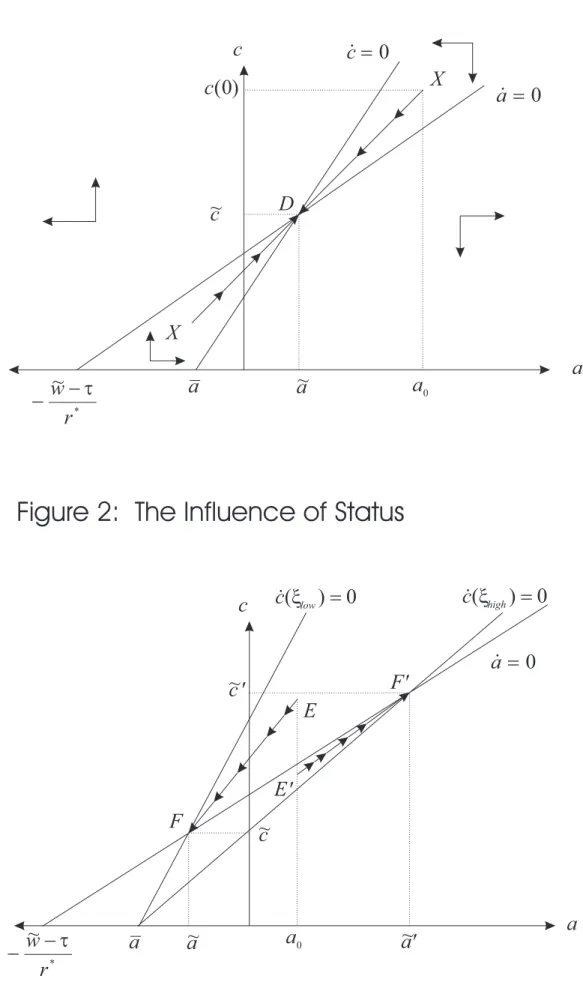

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2, rst describes our general

model of status preference and derivesthe symmetric, intertemporal equilibrium. Along

thestablearm, we showthatconsumption andnetassets always move inthesame direc-

tion. Moreover, as netassets accumulate, theeective rate of returndeclines, converging

to the subjective discount rate, which is its long-run equilibriumvalue.We then param-

eterize theinstantaneous utilityfunction. This will allowus to compare the implications

of dierent \degrees of status consciousness" for the steady-state values of consumption

and net assets, as well as the speed of convergence. Moreover, we show that the degree

of statusconsciousnessdetermineswhether netassetsandconsumption riseorfallduring

thetransitional phase.

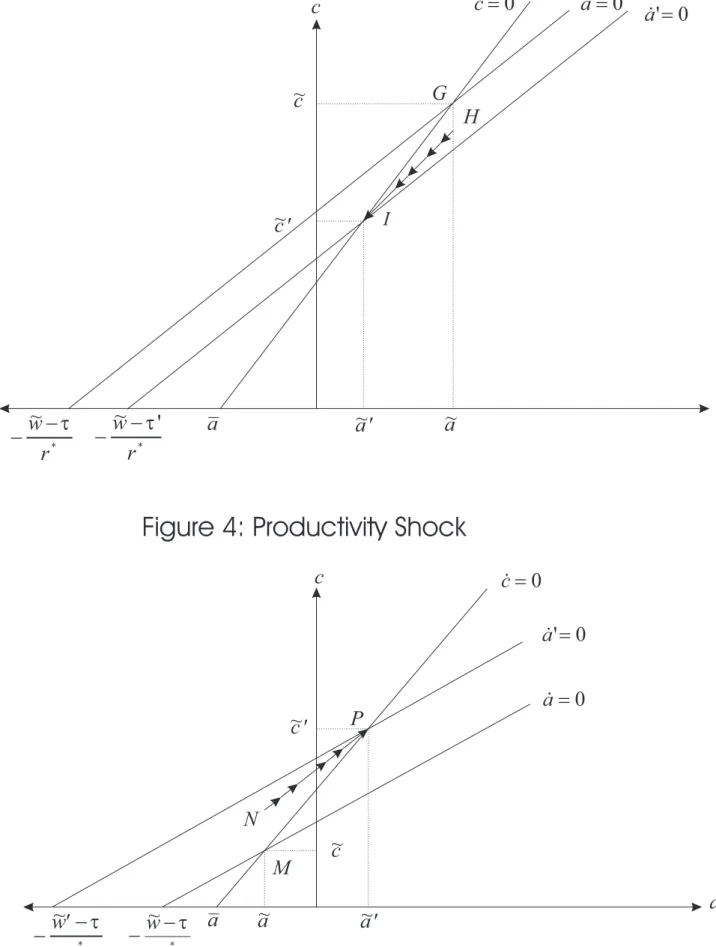

In section 3 we will investigate how status preference aects the adjustment of pri-

vateconsumptionandnetassetstogovernment expenditure,andtotal factorproductivity

shocks. A notable result in thispart of our paperis that in the long run, a rise in gov-

ernmentexpenditure\crowdsout"privateconsumptionbymorethanone-for-one.Thisis

dueto thelong-rundecline,attributableto statuspreference, innetassets,andhence, in

of status consciousness. We obtain an analogous result for a positive productivityshock

inwhichthelong-runrise inconsumptionexceeds thatof after-taxreal wage income due

to highersteady-statenetinterestincome.Weclosethepaperwithconcludingremarksin

section 4.

2 The Model and Intertemporal Equilibrium

2.1 General Specication of Preferences

We begin by assuming that the small open economy is populated by a large number of

identical,innitely-livedagents.Withoutlossofgenerality,wespecifythatthepopulation

size remains constant over time. In contrast to the standard model of the consumer, we

assumethateach agentpossessesthefollowinggeneralinstantaneousutilityfunctionover

ownconsumption,c,and status, s, U =U(c;s),where

U

c

>0, U

s

>0, U

cc

<0, U

ss

0, U

cc U

ss U

2

cs

0, (1)

U

sc U

c U

s U

cc

>0; (2)

lim

c!0 U

c

(c,s)=1, lim

c!1 U

c

(c,s)=0. (3)

According to (1), therepresentative agent derivespositive,thoughdiminishing,marginal

utilityfromownconsumptionandpositiveandnon-increasingmarginalutilityfromstatus,

with theutilityfunctionU jointlyconcave inc and s.

6

Condition (2)imposes normality

on preferences, i.e., that the marginal rate of substitution of status for consumption,

U

s

=U

c

,dependspositivelyon c, while(3)describesthe limitingbehavior of themarginal

utility of consumption. Asindicated in the introduction, we assume that an individual's

status depends on both own netassets (= nonhuman wealth), a, and average net assets

of the private sector, A, i.e., s = s(a;A), where the status function is dened for all

(a;A)2( a ;1)( a;1).

7

Since we do not want to ruleout a priori the possibilitythat

the economyreaches a steady state witha negative stockof privateassets, ascan bethe

6

We will use the following notational conventions.In general, we will suppress avariable's time de-

pendence, i.e,xx(t).Thetimederivativeofxwill bedenotedbyx;_ asteady-statevalue byx.~ Unless

otherwiseindicated,thepartialderivativeofafunctionF withrespecttoxwillbedenotedbyFx.

7

Subsequently,wewilluse\wealth"asashorthandfor\nonhumanwealth".

This lowerbounda can be interpretedas an indicator of domestic residents' aversion to

(ortolerancefor)indebtedness.Inaddition,wealsoassumeforall(a;A)2( a ;1)( a;1)

that status increases in own wealth, decreases in average wealth, and that the marginal

status inown assetsis non-increasing,i.e.:

s

a

>0, s

A

<0, s

aa

0. (4)

Inthebulkofmacroeconomicliteratureonstatuspreference,thestatusfunctiontakesthe

following \ratio" form s(a;A) = '(a=A), ' 0

> 0, ' 00

0, where a=A represents relative

wealth. Note, however, that this formulation yields counter-intuitive results if negative

levels ofwealth arepermitted.For instance,sinces

a

=A 1

' 0

,a negative levelof average

wealth (A < 0) would implythat an increase in own wealth decreases status. Similarly,

s

A

= (a=A 2

)' 0

impliesthatariseinaveragewealthcausesstatustoimprove(i.e.s

A

>0)

ifthe individual'swealth isnegative (a<0). To eliminateanomalies ofthis sort,we will

usethe followingrepresentationofthe statusfunction:

s(a;A)'

a a

A a

; a<0, ' 0

>0, ' 00

0. (5)

According to (5), bothown and average wealth are measured with respectto the \lower

bound", or\minimumvalue", a. It is easilyveriedthat (5) satisesall properties given

in(4) forall(a;A)2( a;1)( a;1).

In order to focus on the inuence of status preference, we make simple assumptions

regardingtheopeneconomy'stechnologicalandnancialmarketpossibilities.Specically,

we assume that domestic physical capital is owned by domestic agents and is rented

in the perfectly competitive global capital market. In addition to physical capital, they

can accumulate wealth in the form of domestic government bonds (the domestic public

sector will be introduced below) and international assets. Agents can also borrow inthe

internationalcreditmarket. Ownwealthathenconsistsofphysicalcapital andnetloans.

Because physical capital and nancial assets are perfect substitutes, they all bear the

same rate of return, equal to the exogenous world interest rate r

. FollowingBarro and

Sala-i-Martin (1995) and Turnovsky(1997), we assume that r

is constant throughtime.

The representative agent inelasticallysupplies one unit of laborand receives a real wage

in addition, that the domestic public sector levies per-capita lump-sum taxes on the

privatesector, wecan expressthe ow budgetconstraint of therepresentative agent as

_ a=r

a+w c, (6)

where the agent's initial exogenous endowment of wealth is a

0

. Employing an innite

horizon, perfect foresight framework,the agent's maximization problemis formulatedas

follows: maximize

Z

1

0

U(c;s)e t

dt;

where is the exogenous rate of pure time preference and s is given by equation (5),

subject to the ow budget constraint (6), the initial condition a(0) = a

0

, and the No-

Ponzi-Game (NPG) condition lim

t!1 ae

r

t

0. A crucialfeature of this optimization

problemisthattherepresentativeagenttakesthetimepathofaveragewealth Aasgiven.

In other words, each individual is small enough to neglect his own contribution to the

average wealth level. The current value Hamiltonianforthisproblemisequalto

H(c;a;)=U

c;'

a a

A a

+(r

a+w c);

where isthe current costate variable that denotesthe current shadow value of wealth.

The necessary conditions for an interior optimum, H

c

= 0 and _

= H

a

, are then

expressed as:

U

c

c;'

a a

A a

=; (7)

_

=( r

) U

s

c;'

a a

A a

' 0

a a

A a

1

A a

. (8)

The assumptionsmade above in (1) and (5) ensure that the Hamiltonian is jointly con-

cave in the control variable c and the state variable a. This impliesthat if the limiting

transversality condition lim

t!1 ae

t

= 0 holds, then the necessary conditions (7){(8)

are suÆcientforoptimality.

Wenowdescribethedomesticpublicsectorandassume,rst,thatithasthefollowing

owbudgetconstraint _

b=r

b+g ,wherebisthestockofper-capitagovernment debt,

grepresentsper-capitagovernmentspending,and,asindicatedabove, isthelevelofper-

capita lump-sum taxes. The government can borrowfrom thedomestic privatesector or