WHAT ARE THE BEST QUALITY OF LIFE MEASUREMENT INSTRUMENTS FOR ECZEMA? PERSPECTIVES ON POPULARITY AND QUALITY AS A CONTRIBUTION TO

Volltext

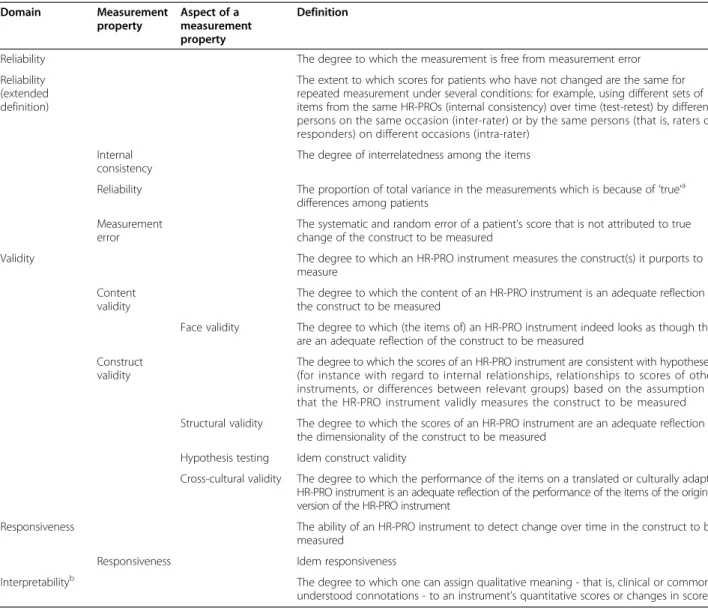

Abbildung

ÄHNLICHE DOKUMENTE

Atopic dermatitis (AD), one of the most frequent inflammatory skin diseases worldwide, is believed to result from a disturbed skin barrier as well as aberrant immune reactions

To produce eczema, and perhaps also many other skin diseases, the chain of events has three important links. They are the group of underlying causes, the group

We found that Crit for checking the monotonicity assump- tion in MSA was affected to a large extent by sample size, the number of misfitting items, and the type of violation of

IRs were defined as the number of patients with events during the risk period divided by the sum of the durations of exposures of the patients during the risk period (time to

Bei einer beruflich verursachten Verschlechterung eines atopischen Ekzems sollte an eine kombinierte Rehabilitation stationär durch die DRV und ambulant im Rahmen des

This study shows that farming status of pregnant mothers was associated with increased gene expression of innate immunity receptors at birth (overall and individually with TLR7

To maintain this function, various cell types in the skin, including keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and innate and adap- tive immune cells, like dendritic cells, macrophages, mast

the responses of the epithelium, we used ALI cultures of bronchial epithelial cells from patients with asthma and control subjects to compare HRV16- induced changes in mRNA

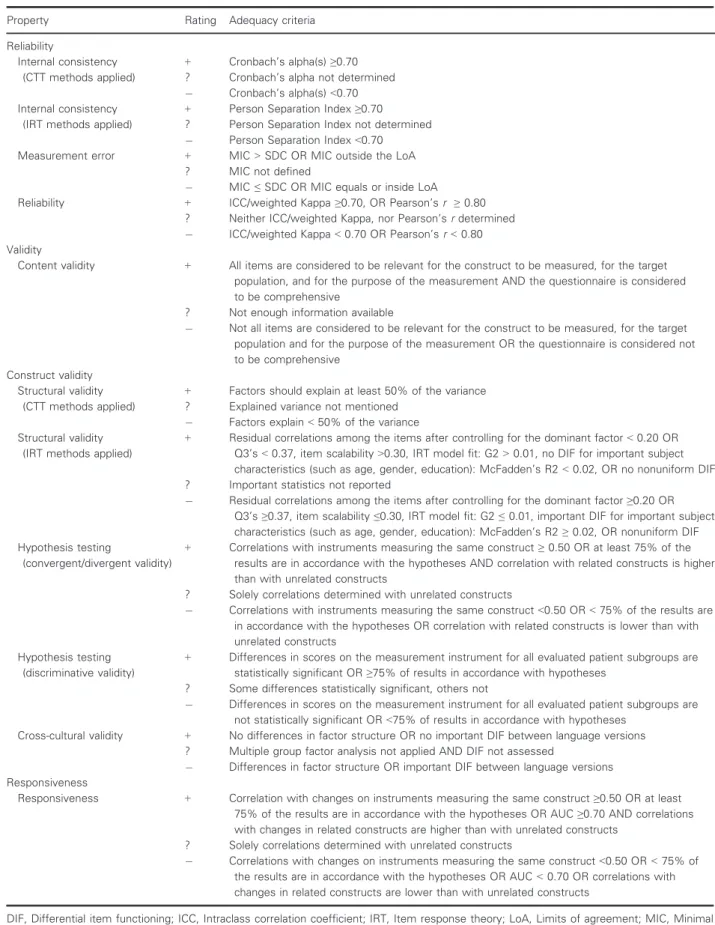

![Table 3 Quality criteria for measurement properties adapted from [11] and [15]](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/1library_info/3940439.1533176/50.892.84.801.142.1054/table-quality-criteria-measurement-properties-adapted.webp)