ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Early Childhood Research Quarterly

Home and preschool learning environments and their relations to the development of early numeracy skills

Yvonne Anders

∗, Hans-Günther Rossbach, Sabine Weinert, Susanne Ebert, Susanne Kuger, Simone Lehrl, Jutta von Maurice

UniversityofBamberg,Germany

a r t i c l e i n f o

Articlehistory:

Received13August2010

Receivedinrevisedform1August2011 Accepted10August2011

Keywords:

Preschoolquality

Homelearningenvironment Numeracyskills

Longitudinalstudy

Internationalchildcareperspectives Cognitivedevelopment

a b s t r a c t

Thisstudyexaminedtheinfluenceofthequalityofhomeandpreschoollearningenvironmentsonthe developmentofearlynumeracyskillsinGermany,drawingonasampleof532childrenin97preschools.

Latentgrowthcurvemodelswereusedtoinvestigateearlynumeracyskillsandtheirdevelopmentfrom thefirst(averageage:3years)tothethirdyear(averageage:5years)ofpreschool.Severalchildandfam- ilybackgroundfactors(e.g.,gender,maternaleducation,socioeconomicstatus),measuresofthehome learningenvironment(e.g.,literacy-andnumeracy-relatedactivities),andmeasuresofpreschoolstruc- turalandprocessquality(e.g.,ECERS-E,ECERS-R)weretestedaspredictorsofnumeracyskillsandtheir development.Theanalysesidentifiedchildandfamilybackgroundfactorsthatpredictednumeracyskills inthefirstyearofpreschoolandtheirdevelopmentoverthethreepointsofmeasurement—particularly gender,parentalnativelanguagestatus(German/other),socioeconomicstatus,andmother’seducational level.Thequalityofthehomelearningenvironmentwasstronglyassociatedwithnumeracyskillsinthe firstyearofpreschool,andthisadvantagewasmaintainedatlaterages.Incontrast,theprocessqualityof thepreschoolwasnotrelatedtonumeracyskillsatthefirstmeasurement,butwassignificantlyrelatedto developmentovertheperiodobserved.Theresultsunderlinethedifferentialimpactofthetwolearning environmentsonthedevelopmentofnumeracyskills.Interactioneffectsareexploredanddiscussed.

© 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Itiswelldocumentedthatchildrenenteringelementaryschool differ in theirlanguage,pre-reading,and earlynumeracy skills andthatthesedifferencesareoftenmaintainedatlaterages(e.g., Dornheim,2008;Dubowy,Ebert,vonMaurice,&Weinert,2008;

Magnuson,Meyers,Ruhm,&Waldfogel,2004;NationalInstitutefor ChildHealthandHumanDevelopmentEarlyChildCareResearch Network [NICHD ECCRN], 2002a, 2005; Sammons et al., 2004;

Tymms,Merell, &Henderson,1997; Weinert,Ebert,&Dubowy, 2010).Promotingschoolreadinessandbetteradjustmenttoschool ishypothesizedtobeanefficientmeansofraisingtheachieve- mentlevelsofallchildren,butespecially ofthosechildrenwho experience a lack of parental support. It hasbeen argued that investinginearlyeducationprogramswillhavelargelong-term monetaryand nonmonetarybenefits(Heckman,2006;Knudsen, Heckman,Cameron,&Shonkoff,2006).Theseexpectationshave

∗Correspondingauthorat:EarlyChildhoodEducation,FacultyofHumanSciences andEducation,UniversityofBamberg,Postbox1549,96045Bamberg,Germany.

Tel.:+499518631821;fax:+499518634821.

E-mailaddress:yvonne.anders@uni-bamberg.de(Y.Anders).

ledtoincreasedstateandfederalsupportforearlyeducationpro- gramsinGermany,andstrategieshaverecentlybeenimplemented tofosterthepromotionofemerging(pre)academicskillssuchas languageskills,numeracy,andscientificthinkingatpreschool.To date,however,empiricalevidenceontheeffectsofpreschooledu- cationinGermanyislimited(Rossbach,Kluczniok,&Kuger,2008).

Of course,children’scognitivedevelopment andeducational careers are also influenced by characteristics of the family and homelearning environment (e.g.,EuropeanChildCareand Education[ECCE]StudyGroup,1999;Melhuishetal.,2008;Sirin, 2005; Taylor, Clayton, & Rowley, 2004). Consequently, studies evaluating the potential benefits of early years education pro- gramsneedtoexaminetheinfluencesofthehomeandpreschool learning environments simultaneously. This article investigates howthetwoenvironmentsinteractinshapingthedevelopment of earlynumeracy skills in preschool-agechildren in Germany.

ResearchconductedinotherEuropeancountriesandintheUnited Stateshashighlightedthepotentialbenefitsofearlyyears edu- cation programs for children’scognitivedevelopment for some yearsnow(ECCEStudyGroup,1999;NICHDECCRN,2002a,2005;

Sammonsetal.,2004).However,emergingnumeracyhasreceived lessresearchattentionthanhasemergingliteracy,especiallywith respecttothenatureandeffectsofthehomelearningenvironment.

0885-2006/$–seefrontmatter© 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.08.003

Yetemergingnumeracyisseenasoneofthemostsignificantpre- dictorsoflaterschoolsuccessinmathematics.Thepresentstudy alsooffersthepossibilitytoexplorehowfindingsfromaGerman samplereflectpreviousresultsfromothercountriesandtoiden- tifyindicatorsofgoodpracticethatareindependentofthenational context.

In the following, we first outline the available research on thecharacteristicsand impactoftheearlyyears homelearning environmentandof preschoolexperience.We thenidentifythe researchdesideratathatareaddressedinthepresentstudy.Finally, wedescribethestudyframeworkandformulateourresearchques- tions.

1.1. Characteristicsandimpactoftheearlyyearshomelearning environment

Thequalityofthehomelearningenvironmentisrelatedtothe availabilityofeducationalresources,suchasbooks,andthenature ofparentingactivities,suchasreadingtothechild,usingcomplex language,playingwithnumbers,counting,andtakingthechildto thelibrary(e.g.,Hart&Risley,1995;Melhuishetal.,2008;Snow

&VanHemel,2008).Studiesexploringthenatureand variation ofearlyyearshomelearningenvironmentshavefoundhighvari- ationbetweenfamilies.Structuralcharacteristics,suchasfamily composition,housing,andincome,aswellasparentaleducational beliefsandexpectationsalsoimpactthequalityofthehomelearn- ingenvironment(e.g.,Bornstein&Bradley,2008;Dowsett,Huston, Imes,&Genettian,2008;Tietze,Rossbach,&Grenner,2005).Specif- ically,resultsindicatethatlowsocioeconomicstatus(SES)andlow parentaleducationaremoderatelyassociatedwithlowqualityof thehomelearningenvironment(Bornstein&Bradley,2008;Foster, Lambert,&Abbott-Shim,2005;Melhuishetal.,2008;Totsika&

Sylva,2004).SonandMorrison(2010)recentlyinvestigatedthe stability ofthe homeenvironment aschildren approach school entry.Ontheonehand,theirresultsindicatedthatthequalityof thehomeenvironment atage36 monthswashighlycorrelated withthequalityofthehomeenvironmentatage54months.On theotherhand,theyfoundthathomeenvironmentsarealsosub- jecttochangeandseemtoimproveaschildrenapproachschool entry.

Numerousstudiesusingdifferentmeasuresofthehomelearn- ingenvironmenthaveshownthatithasaconsiderableinfluence onyoungchildren’scognitivedevelopmentandeducationalout- comes.Forexample,qualityofthehomeenvironmentasmeasured bytheHome Observationfor MeasurementoftheEnvironment Inventory(HOME;Caldwell&Bradley,1984)hasbeenfoundto correlatewithoutcomesincludinggeneralcognitiveability and language(Son &Morrison, 2010;Totsika & Sylva,2004).Other indicatorsofthehomelearningenvironmentassociatedwithbet- tercognitiveoutcomesarequalityofdialogicreading(Whitehurst

&Lonigan,1998),useofcomplexlanguage(Hart&Risley,1995), responsivenessandwarmthininteractions(Bradley,2002), and library visits(Griffin & Morrison,1997; Melhuish et al., 2008).

Withrespect tothe development of earlynumeracy skills, the overallqualityofthehomelearningenvironment(Blevins-Knabe, Whiteside-Mansell,&Selig,2007)aswellasmathematicalactiv- ities such as counting or identifying shapes (Blevins-Knabe &

Musun-Miller, 1996) have been shown to influence children’s mathematicaldevelopment.Thesefindingsaresupportedbyother studiesshowingthatparentsofpreschoolerscansuccessfullypro- videtheirchildrenwithspecificopportunitiestouseandextend their early numeracy concepts and skills (Jacobs, Davis-Kean, Bleeker,Eccles,&Malanchuk,2005; LeFevre,Clarke,&Stringer, 2002;LeFevreetal.,2009).

1.2. Characteristicsandimpactofpreschoolexperience

Conceptualizations of the quality of the preschool learning environmentcover multipledimensionsand relatetostructural characteristics(e.g.,classsize,staffqualificationlevels),teachers’

beliefsandorientationswithrespecttolearningprocesses,andthe processqualityoftheinteractionsbetweenteachersandchildren (NICHDECCRN,2002b;Piantaetal.,2005).Processqualityinvolves globalaspectssuchaschild-appropriatebehaviorandwarmcli- mate(Harms,Clifford,&Cryer,1998)aswellasdomain-specific stimulation in areas such as verbal and (pre)reading literacy, numeracy,andscientificliteracy(Kuger&Kluczniok,2008;Sylva, Siraj-Blatchford,&Taggart,2003).Researchhasprovidedinsights intovariationinpreschoolquality.Notonlyaredifferencesacross individualpreschoolsortypesofpreschoolsettingslarge,butthe legalframeworkvariesgreatlyacrosscountriesandfederalstates (Cryer,Tietze,Burchinal,Leal,&Palacios,1999;Earlyetal.,2007;

ECCEStudyGroup,1999;Sylva,2010).Additionally,it hasbeen shownthatthelevelofprocessqualityisassociatedwithstruc- turalcharacteristicsofthepreschoolsettingandclass(Earlyetal., 2010;Piantaetal.,2005;Tietzeetal.,1998).DrawingonaGerman sampleofpreschools,KugerandKluczniok(2008)showedthatdif- ferentaspectsofprocessquality(climate,promotionofliteracyand numeracy)wererelatedtotheaverageageofthechildreninthe classandtotheproportionofchildrenwithanativelanguageother thanGerman.

Large-scalelongitudinalstudieshaveproduced accumulating evidenceforbeneficialeffectsofpreschooleducationonstudents’

cognitivedevelopmentandoutcomes(e.g.,Belskyetal.,2007;ECCE StudyGroup,1999;NICHDECCRN,2003,2005;Peisner-Feinberg etal.,2001;Sylva,Melhuish,Sammons,Siraj-Blatchford,&Taggart, 2004).Whereas theevidencefor short-and medium-termaca- demicbenefitsofearlyeducationorpreschoolprogramsseemsto becompelling,findingsonlonger-termbenefitsaremixed.Itseems thattheprocessqualityofthepreschoolattendedisacrucialfactor inthemagnitudeandpersistenceofbeneficialeffects.Indeed,the effectsofhigh-qualitypreschooleducationorintensiveprograms oncognitiveskillshavebeenshowntopersistuptotheagesof 8,10,11oreven15years(Andersetal.,2011;Belskyetal.,2007;

ECCEStudyGroup,1999;Gorey,2001;Peisner-Feinbergetal.,2001;

Sammons,Sylva,etal.,2008;Vandelletal.,2010).

1.3. Interactiveeffectsofhomeandpreschoollearning environments

It isaccepted thattheeffects of preschooleducationcanbe reliablyevaluatedonlyiffamilyandhomecharacteristicsarecon- sideredatthesametime.Whereasolderstudiestendedtocontrol forsocioeconomicandfamilybackgroundcharacteristicswithout investigatingthedistinctinfluenceofthehomelearningenviron- mentondevelopment,recentstudieshaveexaminedtheinfluence ofbothfactors(e.g.,Melhuish,2010;NICHDECCRN,2006).Nev- ertheless,fewstudieshaveyetexplicitlyanalyzedtheinteractive effectsofthetwoenvironments,althoughthepotentialbenefits oftheamountandqualityofpreschooleducationmaydependon thequalityofthehomelearningenvironmentandviceversa.The findingsofBurchinal,Peisner-Feinberg,Pianta,andHowes(2002) indicatethatmaternaleducation,parents’caregivingpractices,and parents’attitudesarethestrongestpredictorsofchildoutcomes, evenamongthosechildrenwhoexperiencefull-timenonmaternal childcare.Adi-JaphaandKlein(2009)examinedtheassociationsof parentingqualitywithcognitiveoutcomessuchasreceptivelan- guageandschoolreadinessamongchildrenexperiencingvarying amountsofchildcare.Theyfoundstrongerassociationsamongchil- drenwhoexperiencedmediumamountsofchildcarethanamong thosewhoexperiencedhighamountsofchildcare.However,the

associationswerenotweaker amongchildren whoexperienced primarilymaternalcare.The findingsofBrooks-Gunn, Han,and Waldfogel(2010)indicatethatmaternalemploymentduringthe firstyearoflifemaybeassociatedwiththeamountofchildcare, butmayalsobepositivelyrelatedtothequalityofthechildcare andhomeenvironments.

Findingsoninteractiveeffects of childcarequality andqual- ityofthehomelearningenvironmentaremixed.Summarizingits results,theNICHDstudygroup(NICHDECCRN,2006)stated,“we donotseeaconsistentpatternsuggestingmoreoptimaloutcomes associatedwithchildcareforthelowestparentingquartileorless optimaloutcomesassociatedwithchildcareforthehighestparent- ingquartile”(p.110).Bryant,Burchinal,Lau,andSparling(1994) foundpositiveeffectsofclassroomqualityoncognitiveoutcomes, withchildren fromstimulatinghomeenvironmentsseemingto benefitevenmorefromhigh-qualitypreschoolthanchildrenfrom lessstimulatinghomes.Incontrast,afteranalyzingthecombined effectsofpreschoolexperienceandhomelearningenvironment oncognitiveoutcomesatage10,Sammons,Anders,etal.(2008) concludedthatthequalityofthehomelearningenvironmentis especiallyimportantforchildrenwhoarenotinpreschoolorwho attendlow-qualityorlow-effectivepreschools.Inturn,thequality andeffectivenessofthepreschoolsettingiscriticalforchildren’s learning progress, especially when they receive little cognitive stimulationathome.Hence,thefewstudiesexamininginteractive or compensatory effects of home and preschool learning envi- ronmentsonchildren’scognitivedevelopmenthaveproducedan inconsistentpatternofresults.

1.4. Desiderataforresearch

Thisstudyaddresses researchquestions and methodological issues that have received little attention in existing empirical research.Itsfirstfocusisonthedomainspecificityof cognitive stimulationinhomeandpreschoolsettings.Specifically,numer- acy involves other facets of knowledge than does verbal and (pre)readingliteracy(e.g.,numbersandquantitiesasopposedto lettersandsounds).Itseemsreasonabletoassumethatnumeracy- related activitiesand stimulation,such ascountingor teaching numbers,areespeciallybeneficialforthedevelopmentofnumeracy skills.However,languageskillsandgeneralcognitivemechanisms relevantfortheacquisitionof(pre)readingliteracymayalsofos- terearlynumeracyskills(e.g.,Aiken,1972).Forexample,children needbothlinguisticcompetenceanddomain-generalskillssuchas logicalthinkingtotakeadvantageofinstruction.Thus,verbaland (pre)reading-relatedactivitiesandstimulationmayalsofosterthe developmentofnumeracyskills.Inanycase,itseemsnecessaryto disentangletheeffectsofthetwodomains.

Indeed,establishedconceptsandmeasuresoftheprocessqual- ity of preschooldistinguish betweenlearning opportunities for emergingreadingliteracyandnumeracy(Kuger&Kluczniok,2008;

Sylvaetal.,2003).Wheninvestigatingtheimpactofprocessqual- ityonchildren’scognitiveoutcomes,however,researchersoften useglobalqualityindicatorsrather thandistinguishingthetwo domains.Mostdefinitionsoftheearlyyearshomelearningenvi- ronmenteitherfocusonverbaland(pre)reading-relatedactivities andresources(e.g.,Griffin&Morrison,1997; Leseman,Scheele, Mayo,&Messer,2007;Neuman,Copple,&Bredekamp,2000)or donotdifferentiatebetweenactivitiespromotingverballiteracy ornumeracy (e.g.,Adi-Japha&Klein, 2009;Bryantet al.,1994;

Burchinaletal.,2002;Melhuishetal.,2008).Comparativelyfew studieshavefocusedexclusivelyonnumeracy-relatedactivitiesin thefamilyandtheirrelationstonumeracyskillsormathematics achievement(e.g.,Blevins-Knabe&Musun-Miller,1996;LeFevre etal.,2009;Starkey,Klein,&Wakeley,2004;Tudge&Doucet,2004).

Inthisstudy,wedistinguishbetweenthetwodomainsanddemon- stratethevalueofsuchanapproach.

Animportantmethodologicalchallengerelatestotheageofthe childrenatentrytopreschoolandtothestudy.Bythetimechildren enter preschool(e.g.,at age3 years),variousfactors—especially the home learning environment—may already have influenced theircognitivedevelopmentforsometime,andthedifferencesin competenciesandskillsassociatedwiththehomelearningenvi- ronment may be maintained throughout the preschool period.

Additionally, researchersareoftenonlyabletobeginrecruiting childrenatentrytopreschool,meaningthatchildrenhavebeen inpreschoolfor severalmonthsbeforetheircognitiveskillsare measuredforthefirsttime.Thus,someofthevariationinthebase- lineassessmentmaybea resultofpreschoolexperienceandits quality.Thepossibleimpactofchildren’spreviousexperienceson thebaselinemeasureisoftendisregardedinthechoiceofstatis- tical methodsandthediscussionoffindings;thismayresultin theunderestimationandundervaluationoftheeffectsofthehome learningenvironmentorpreschoolexperience.

Third,thefewexistingfindingsontheinteractiveeffectsofhome and preschoollearning environments reveal theneedfor more studiesexaminingthesecomplexrelationsindepth.Thepresent study wasdesigned to contribute toa better understandingof howhomeandpreschoollearningenvironmentsarerelatedtothe developmentofearlynumeracyskills,addressingallofthepoints mentionedabove.

1.5. Thepresentstudy

ThisstudyispartofthelongitudinalBiKSprojectonEducational Processes,CompetenceDevelopment,andSelectionDecisionsat Pre-andElementarySchoolAge(German:Bildungsprozesse,Kom- petenzentwicklung und Selektionsentscheidungen im Vor- und Grundschulalter),whichwasfundedbytheGermanResearchFoun- dation(DFG).TheBiKS3–10substudytracksthedevelopmentof 547childrenattending97preschoolsintwoGermanfederalstates (BavariaandHesse)since2005.PreschoolisvoluntaryinGermany, andmostpreschoolersstartattheageof3years.Unlikepreschool settings in many other countries, children are often placed in mixed-ageclasses.Thus,theageofchildrenwithinoneclassoften rangesbetween 3and 6 years. BiKS3–10hascollecteda wide rangeof dataonthechildren, theirfamily background,and the preschoolstheyattended,makingitpossibletoinvestigatethechil- dren’scognitivedevelopment,theinfluencesoffamilybackground andpreschool,andtheformationofeducationaldecisions(Schmidt etal.,2009;vonMauriceetal.,2007).Inparticular,thestudyaimed toprovideacompletepictureofchildren’slearningenvironments atpreschoolage.Whereasmostpreviousstudieshaveassessedthe homelearningenvironmentsolelybymeansofparentalquestion- nairesandinterviewsfocusingonresourcesandparentalactivities promotingearlyliteracy,BiKScombinedinterviewsandquestion- naireswithobservationsinthefamiliesanddistinguishedbetween resourcesandactivitiesrelatedtoverbalor(pre)readingliteracy,on theonehand,andnumeracy,ontheother.Arepeatedmeasurement designwasimplementedforhomeandpreschoolcharacteristicsas wellasfortheoutcomemeasures.BiKSthusgoesfarbeyondpre- viousstudies(ECCEStudyGroup,1999)oneducationalcareersand theirinfluencingfactorsinthisagerangeinGermany.

Inthepresentinvestigation,weexploreearlynumeracyskills andgrowthinthiscognitivedomainovertwoyearsofpreschool (age3–5years),addressingfiveresearchquestions.First,weseek toidentifytheinfluenceofseveralchildandfamily background factors(e.g.,gender,SES,maternaleducation)ondevelopmental progress.Second,weexaminetheinfluenceofdifferentaspectsof thehomelearningenvironment(qualityofstimulationinnumer- acyand[pre]readingliteracy)ondevelopment.Third,wetestthe

powerofmeasuresofpreschoolexperience(structuralandpro- cessquality characteristicsin differentdomains) topredictthe developmentofnumeracyskills.Fourth,weinvestigatewhether theeffectofpreschoolqualityonbaselineachievementleveland growthdependsontheamountoftimethechildhasspentinthat preschoolatstudyentry.Finally,itexamineswhethertheeffectof preschoolprocessqualityisthesameamongchildrenexposedto homelearningenvironmentsofdifferentqualities.

2. Methods

2.1. Procedureandsample

AlldatawereobtainedinthecontextoftheBiKS3–10study (vonMauriceetal.,2007).Thesampleconsistedof532childrenfor whomatleastonevalidoutcomemeasureandpredictorwereavail- able(i.e.,97.28%oftheoriginalsamplerecruitedfrom97preschool classesin2005).Itwasdrawnfromeightregionsintwofederal states(BavariaandHesse)thatcoverawiderangeoflivingcondi- tionsinGermanyintermsofenvironmentalconditionsaswellas familysocioeconomicandculturalbackgrounds.Thetargetpopula- tionwaschildrenduetobeenrolledinschoolinfall2008.Trained examinerstestedthechildrenindividually.Theaveragenumber ofchildrenassessedperclasswas5.48.Notethatthisnumberis notequivalenttoclasssize,asmostpreschoolclassesconsisted ofmixedagegroups,suchthatnotallchildreninaclassmetthe inclusioncriterion.

Assessmentsincludedabatteryofstandardizedtestscovering thedomainsofverbaldevelopment,non-verbalreasoning,mem- ory,and specificschool-relevantskills.Inthepresentstudy,we analyzethedevelopmentofearlynumeracyskillsoverthreemea- surementpoints.Theparticipatingchildrenwereagedonaverage 37monthsatpreschoolentry(min.=23,max.=50),45monthsat thefirstassessment(min.=34,max.=57),56monthsatthesec- ondassessment(min.=46,max.=67),and68monthsatthethird assessment (min.=58, max.=76).The vast majority of children wereintheirfirstofthreeyearsofpreschooleducationatbase- lineassessment,andtheintervalbetweeneachoftheassessments wasapproximatelyoneyear.Accordingly,formostparticipating children,thethreemeasurementpointscoveredthefirst,second, andthirdyearofpreschoolexperience.Theagerangeobserved wasmainlyaneffectofthedifferingschoolenrolmentprocedures inthefederalstatesofBavaria andHesse. Inadditiontocogni- tiveoutcomes,dataonawiderangeofbackgroundvariableswas collectedthroughparentalinterviewsandquestionnaires.Parents reportedontheirfamilystructure,occupationalandeducational background,andparent–childactivitiesandroutines.Furtherinfor- mationonthechild’shomeenvironment wasobtainedthrough observationsconductedeachyearintheparticipatingchildren’s homes.Structuralcharacteristicsandmeasuresofpreschoolpro- cessqualitywereobtainedthroughinterviewswiththeheadsofthe preschools,staffquestionnaires,andobservations.Staffinterviews wereconductedtwiceayear,andtwoobservationsofthepreschool settingswereconductedbetweenthefirstandthirdmeasurement.

Ofthechildren(48.12%girls),9.96%hadoneparentwithanative languageotherthanGermanand9.59%had twoparentswitha nativelanguageotherthanGerman.Withrespecttomaternaledu- cation,24.44%ofmothershadnoqualificationsorhadgraduated fromthevocationaltrackofthethree-tierGermansecondarysys- tem,35.53%hadgraduatedfromtheintermediatetrack,and34.02%

hadgraduatedfromtheacademictrack.Theremaining5.26%held anyothertypeofqualification.Duetothesamplingdesign,65.23%

ofthechildrenwerefromBavariaand34.78%fromHesse.Thesam- plecanbeassumedtoberepresentativeoftheregionsandfederal statesselected.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Outcomemeasures

Children’searlynumeracyskillswereassessedusingthearith- meticsubscaleoftheGermanversionoftheKaufmanAssessment BatteryforChildren(KABC;Melchers&Preuss,2003).Thisscale measureschildren’sskillsincounting,identifyingnumbers,knowl- edgeofshapes,andunderstandingofearlymathematicalconcepts like additionor subtraction. Although the instrument doesnot coverallaspectsofnumeracydevelopmentduringpreschoolage, itisinternationallywellknownandestablished.Numeracyskills ascoveredbythearithmeticsubscaleareconsideredtobepredic- tiveforlatermathematicsachievementinschool(Dornheim,2008;

Jordan,Glutting,&Ramineni,2010).In contrasttootherinstru- ments,itcanbeappliedoverawideagerange.

Thetestisorganizedintosetsofthreetofiveitemsofincreasing difficulty.Testingisstoppedwhenachildanswersallitemsina subsetincorrectly.Thetestitemsareembeddedinastoryabouta familyvisitingazoo,whichispresentedverballywithaccompany- ingpictures.Insets1and2,thechildhastocountobjects,identify numeralsupto10,andidentifytwo-dimensionalshapes(e.g.,point toatriangle).Insets3and4,thechildhastosolvevariousnumer- icalproblemsinthenumberrangeupto10:comparingquantities ofpicturedobjects(e.g.,“Aretheremorechildrenormoreseals?”), understandingnumbersassymbols(e.g.,“Whatnumberismiss- inghere?”),andsolvingverballypresentedsubtractionproblems supportedbypictures.Insets4and5,thechildhastoreadnum- bersgreaterthan10,solveverballypresentedarithmeticproblems (subtractionandaddition)thatcrossthe“10”boundary,anddo simplemultiplicationanddivisiontasks(e.g.,“Thezoohastwiceas manygiraffesasgoats.Thezoohasfivegoats.Howmanygiraffes arethereinthezoo?”).Fromset6,children’sskillsindealingwith numbershigherthan100andwithscaleunitsareassessed,aswell astheirabilitytosolvemorecomplexmultiplicationanddivision tasksembeddedinthestory.Childrenscoreonepointforeachitem answeredcorrectly.Inthisstudy,weusedrawscoresinthefurther analyses,allowingchangeovertimetobemoreeasilydocumented.

2.2.2. Predictors

2.2.2.1. Childandfamilybackgroundfactors. Variouschildandfam- ilybackgroundfactorsmayinfluencechildren’sachievementand progress.Thepresentsampleisrelativelylarge.Nevertheless,the numberofchildandfamilybackgroundfactorsincludedintheanal- yses neededtobekeptwithina reasonablelevel toensurethe reliabilityoftheestimatesandtoavoidproblemsofmulticollinear- ity.Basedontheliteratureandaftercarefulpreliminaryanalyses, weselectedthefollowingsetofvariables:gender,ageinmonths, parentalnativelanguagestatus(German/other),highestsocioeco- nomicstatusinthefamily(SES),maternaleducation,andageat entrytopreschool.TheInternationalSocioeconomicIndexofOccu- pationalStatus(ISEI;Ganzeboom,DeGraaf,&Treiman,1992)was usedasameasureoffamilySES.Thismeasureisbasedonincome, indicatorsofeducationallevel,andoccupation.

2.2.2.2. Home learning environment (HLE). Characteristics that indicatethecapacityoftheearlyyearshomelearningenvironment topromote(pre)readingliteracyandnumeracyskillswereassessed by(a)speciallyconstructedquestionnairesandinterviews,(b)the adaptedversionoftheEarlyChildhoodHomeObservationforMea- surementof the Environment(HOME 3–6; Caldwell& Bradley, 1984),and(c)asemi-standardizedreadingtaskcalledtheFamily RatingScale(Kugeretal.,2005).Inthistask,theprimarycaregiver andthechildwereaskedtojointlyreadapicturebookprovided bytheresearcher.Thepicturesinthebook(e.g.,showingazoo, acircus,atrainstation,adoctor’soffice,andabakery)included numbersandletters,differentsetsofobjects,shapes,andpatterns.

Thesehiddencuescouldbeusedbytheparenttodevelopthechild’s understandingofmathematicalandlanguageconcepts.Thequality ofinteractionsbetweentheprimarycaregiverandthechildwere ratedbytrainedobserversusingastandardizedratingsystem.

Twoscalemeasuresweredeveloped toassess thequalityof thehomeenvironmentintermsofpromoting(pre)readingliter- acy and numeracy skills,based ondata from allthree sources.

TheHLEverbaland(pre)readingliteracyscalecontains10items tappingliteracy-relatedactivitiesandaccesstomaterialthatstim- ulatesverbaland(pre)readingliteracyexperiences.Itemsfromthe HOMEinventoryincludedthecompositescoreweretoysforfree expression,numberofchildren’sbooks,booksinthehousehold, stimulationtolearnthealphabet,andstimulationtolearntoread.

ItemsfromtheFamilyRatingScalewereuseofquestionsininterac- tion,amountoffreediscussion,interactionsregardingletters,and phonologicalcues.Additionally,theparentquestionnairetapped frequencyofsharedbookreading.Internalconsistency(Cronbach’s alpha)atthethreemeasurementpointswas0.60,0.67,and0.63, respectively. TheHLE numeracy scale consistsof10 items tap- pingnumeracy-relatedactivitiesandaccesstomaterialsthoughtto stimulatenumeracyexperiences.ItemsfromtheHOMEinventory weretoystoteachcolorsandshapes,toystolearnnumbers,stim- ulationtolearnshapes,stimulationtolearncolors,stimulationto learnspatialrelationships,stimulationtolearndigits,stimulation tolearncounting.ItemsfromtheFamilyRatingScalewereinter- actionregardingdigits,interactionregardingshapeandspace,and interactionregardingcomparingandclassifying.Internalconsis- tency(Cronbach’salpha)atthethreemeasurementpointswas0.66, 0.73,and0.71,respectively.Forthefollowinganalyses,thescales werestandardizedtohaveapotentialrangefrom0to1,andtwo indicatorsrepresentingoverallqualityinpromoting(pre)reading literacyand numeracywerederivedbytakingthemeansofthe compositesoverthethreemeasurements.Thecorrelationbetween thetwoscaleswasmoderate,atr=0.62,indicatingthatcognitive promotionofthetwodomainsathomewasbothinterrelatedand distinct.

2.2.2.3. Structural (quality)characteristicsof the preschool. These factorsincludedtheproportionofchildrenwhoseparentshada nativelanguageotherthanGerman,classsize, child–staffratio, amountofspace(m2)perchild,averageageoftheclass,andfederal state.Staffqualificationlevelscouldnotbeincludedintheanaly- sesduetothecurrentlackofvarianceamongpreschoolteachersin Germany.

2.2.2.4. Indicatorsofpreschool processquality. Thismeasurewas basedonresearchers’observations ofeachpreschoolsetting on theGermanversionsoftheECERS-R(Harmsetal.,1998;Tietze, Schuster,Grenner,&Rossbach,2007)andtheECERS-E(Rossbach

&Tietze, 2007;Sylvaetal.,2003).TheECERS-Ris ameasureof theglobalqualityof preschools,capturingaspectsofthephysi- calsetting,curriculum,caregiver–childinteractions,health,safety, schedulingoftime,indoorandoutdoorplay,spaces,teacherqual- ifications,playmaterials,administration,andmeetingstaffneeds.

TheECERS-Efocusesonfoureducationalaspects:thequalityof learningenvironmentsforverballiteracy,mathematics,andsci- enceliteracy,and cateringfor diversity andindividual learning needs. The overall ECERS-Rand ECERS-E scores as wellas the ECERS-Eliteracyandmathematicsscalesareusedinthefollow- inganalyses.Althoughsomepreschoolcharacteristicsarenaturally subjecttochange(e.g.,classcomposition),thecorrelationsbetween themeasurementpointsweremoderate.Tokeepthecomplexity ofourstatisticalmodelswithinreasonablelimits,weusedaverage scoresacrossthethreemeasurementpointsforallpreschoolmea- suresinthefollowinganalyses.Asmeasuresofcentraltendency

overtime,thesemeansaremoreaccuratethanameasurebasedon asingleassessment.

2.3. Statisticalanalyses

Weexaminedinfluencesonthedevelopmentofnumeracyskills overthreerepeatedmeasurements(numeracyskillsatfirst,second, andthirdassessment)byfittinglatentlineargrowthmodelstothe datausingMPlusversion5.2(Muthén&Muthén,2008).Modelfit wasevaluatedwithreferencetotheRMSEAandCFI,usingthecri- teriasuggestedbyHuandBentler(1999).Thedatahaveanested structure,withchildrenbeingnestedinpreschoolclasses.Although thenumberofchildrenperpreschoolclasswasratherlow,ignor- ingthemultilevelstructuremighthaveledtounreliablestandard errorsofthecoefficientsinthemodel(Raudenbush&Bryk,2002).

Thus,standarderrorsadjustedforthemultilevelstructureofthe datawereestimated.Missingdataareapotentiallyseriousprob- leminalllarge-scalelongitudinalstudies;inourstudy,missings onindividualvariables rangedfrom0to19%.Thereis growing consensusthatimputationofmissingobservationsormaximum- likelihoodapproachesarepreferabletoadhocmethodssuchas pairwiseorlistwisedeletion(Enders&Bandalos,2001;Graham

&Hofer,2000;Little&Rubin,1987).Therefore,wechosethefull informationmaximumlikelihood(FIML)approach(e.g.,Arbuckle, 1996)implementedinMPlus,whichusesallavailabledatatoesti- mate model parameters.Selection biasmay beanotherserious probleminnonrandomizedlongitudinalstudiesthatcanpoten- tiallyleadtounreliableresults(e.g.,NICHDECCRN&Duncan,2003).

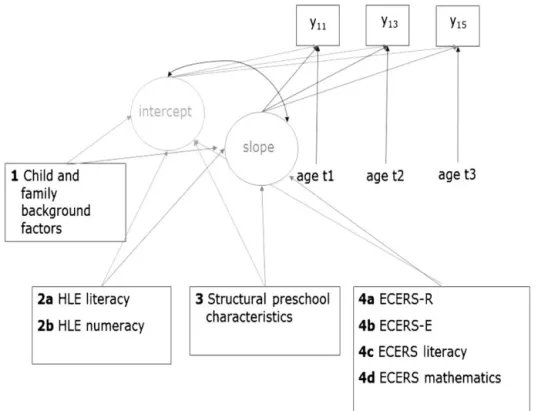

Preliminaryanalysesindicatedthatselectionbiaswaslowinthe presentsample.However,toaccountforpossiblebias,wechose a covariateapproachand includedchildandfamily background indicators(e.g.,SES,maternaleducationallevel,parentalnativelan- guagestatus)thatmightbecorrelatedwiththeoutcomeaswellas withindicatorsofthequalityoflearningenvironments.Astepwise analysisprocedurewasused,asillustratedinFig.1.

First,anullmodelwithaninterceptrepresentinginitialachieve- ment and a linear slope representing growth was specified, consideringonly ageat assessment asa predictorof numeracy skills. We assumed the outcome measures to be highly sensi- tivetochildren’sage.Becausetheintervalbetweenassessments wasnotidenticalforallchildren, ageatassessmentwasthere- foretreatedasa time-varyingpredictor(nullmodel).Childand family background factors were then tested as factors poten- tiallyinfluencinginitialachievementlevel(intercept)andgrowth (slope)(Model1).Inanextstep,wetestedthepredictivepower ofthequalityofthehomelearningenvironment,controllingfor the child and family background factors used in Model 1. The twoHLEindicators(literacyandnumeracy)wereexaminedsepa- rately(Models2aand2b),allowingustodisentangletheeffectsof domain-specificcognitivestimulationinthehomeenvironment.

Third,thestructural (quality)characteristicsofpreschools were includedinthemodel,whilecontrollingforchildandfamilyback- ground factorsand the HLE indicators(Model 3).In thefourth step,indicators ofpreschoolprocessquality(ECERS-R, ECERS-E, ECERS-literacy,ECERS-numeracy)weretestedindividually,while controllingforchild,familybackground,HLE,andpreschoolstruc- turalcharacteristics(Models4a–d).Theeffectsoftheindicatorsof preschoolprocessqualityweretestedseparately,allowingusto disentangletheeffectsofdomain-specificcognitivestimulationin preschool.Finally,interactiontermswerespecifiedandincludedin themodel(notshowninFig.1).Notethatweadoptedasociosys- temic approach and adjusted the stepwise analysis procedure accordingly.Inthisapproach,theeffectsofprocessindicatorsare examinedwhilecontrollingforbackgroundandstructuralcharac- teristics.Similaranalysisstrategieshavebeenusedinotherstudies (e.g.,Sammons,Anders,etal.,2008;Sammons,Sylva,etal.,2008).

Fig.1. Latentgrowthcurveanalysis:stepwiseprocedure.

However,thepatternofresultsobtainedinourstudyremained stablewhentheorderinwhichthepredictorswereincludedinthe modelwaschanged.

All continuous predictors were z-standardized before being included in the model. Preschool indicators were centered at preschoollevel.Afterwards,coefficientswerepartiallystandard- izedusingthevariancesofthecontinuouslatentvariablesonly.

3. Results

First,wepresentthedescriptivedatathatmotivatedthemul- tivariateanalyses.Wethenreporttheresultsofthelatentgrowth curvemodelsandanswertheresearchquestionsaddressed.

3.1. Descriptivefindings

Table1showsdescriptivestatisticsfortheoutcomemeasures, theaggregatedscalesassessingqualityofthehomelearningenvi- ronment,aswellasstructuralcharacteristicsandprocessquality indicatorsoftheparticipatingpreschools.Descriptivesreportedfor thehomelearningenvironmentandpreschoolcharacteristicsare meanscoresofall availablemeasures(questionnaires,observa- tions)acrossthethreemeasurementpoints.

The results show that children’s mean arithmetic scores increasedsignificantlyovertime.TheoverallmeanHLEscores(pos- siblerange:0–1)indicatedsignificantlyhigheraveragescoresfor literacy(M=0.53)thanfornumeracy(M=0.53),t=17.83,df=512, p<0.001,suggesting that literacy-related parent–childactivities (e.g.,readingtothechild)weremorefrequentinoursamplethan werenumeracy-relatedactivities(e.g.,countingwiththechild), and that the children had better access to books to than toys andgamesthatfacilitatethelearningofnumbers.Withregardto preschoolcharacteristics,theindicatorsofprocessqualityareof particularinterest(notethatthepossiblerangeofECERSratings is1–7).Weconsideredpreschoolsratedlowerthan3asbeingof lowquality,thoseratedbetween3and5asbeingofmediumqual- ity,andthoserated5andaboveasbeingofhighquality(Harms

etal.,1998;Sylvaetal.,2003).Onaverage,thequalityofpreschools inoursample,especiallyintermsofpromotingdomain-specific skillsandabilities(ECERS-E,ECERS-mathematics,ECERS-literacy), can thus be described as low or medium. Indeed, this pattern seemstoberepresentativeforpreschoolsinGermany(Kuger&

Kluczniok,2008;Tietzeetal.,1998)andothercountries(e.g.,Sylva, 2010).

Bivariate correlations among all predictor variables were alsoexaminedbeforethemultivariateanalyseswereconducted.

Table1

Descriptivestatistics.

Characteristic M SD Min. Max.

Childlevel(N=532) Outcome

Arithmeticscoret1 4.96 3.37 0 14

Arithmeticscoret2 10.40 3.91 0 20

Arithmeticscoret3 15.08 3.74 2 27

Homelearningenvironment

HLE-literacy 0.53 0.12 0.06 0.84

HLE-numeracy 0.44 0.14 0 0.81

Preschoollevel(N=97) Structuralcharacteristics

Classsize 19.83 4.84 5 50

Averageageofchildrenin theclass

5.01 0.28 3.67 5.60

Child–staffratio 10.67 2.70 5.13 21.50

Proportionofchildren whoseparentshadanative languageotherthanGerman

0.21 0.22 0 0.89

Amountofspace(m2)per child

3.55 2.82 1.46 19.62

Indicatorsofprocessquality

ECERS-R 3.73 0.58 2.39 5.03

ECERS-E 2.88 0.58 1.63 4.07

ECERS-literacy 3.24 0.74 1.67 4.75

ECERS-mathematics 2.52 0.84 1.17 4.50

Note:Arithmeticscoresareaveragerawscores(non-standardized).Indicatorsofthe homelearningenvironmentandpreschoolcharacteristicsareaveragescoresacross thethreemeasurementpoints.

Most correlations were low to moderate. However, there was no indication of multicollinearity problems in the subsequent analyses.

3.2. Howdochildandfamilybackgroundfactorsandhome learningenvironmentrelatetothedevelopmentofnumeracy skills?(Models1,2a,2b)

The relations between child and family background factors, homelearningenvironment,and thedevelopmentofnumeracy skills were examined using growth curve models as described above.Thenullmodelconsideringonlyageatassessmentasatime- varyingpredictorconfirmedthelineargrowthofnumeracyskills overtimeandthatchildagewasasignificantpredictoratallmea- surementpoints(year1:b=0.47,year2:b=0.49,year3:b=0.44, ps<0.001,unstandardizedcoefficients).InModel1,childandfam- ilybackgroundfactorswereincludedasfurtherpredictors(Table2).

Wefoundthatmother’seducationhadasignificantinfluenceon initialnumeracyskills(intercept)butnotonlatergrowth(slope), whereasgender,parentalnativelanguagestatus,andSESexplained varianceintheinterceptaswellasintheslope.Girlsstartedwitha higherlevelofnumeracy(b=−0.36,p<0.001),butboyscaughtup overtheperiodofinvestigation(b=0.60,p<0.001).Childrenwhose parents’nativelanguagewasnotGermanhadlowernumeracylev- elsatthefirstassessment,especiallyifbothparentshadanative languageotherthanGerman(b=−1.21,p<0.001).However,this groupofchildrenalsoshowedrelativelystrongergrowth(b=1.01, p<0.001),catchingupwiththeirpeers,althoughnotclosingthe achievementgapcompletely.Inspectionof themean KABCraw scoresillustratesthispoint:Childrenwhoseparentsbothhad a nativelanguageotherthanGermanhadmeanarithmeticscoresof 2.22atage3and13.28atage5.Bycomparison,childrenofnative Germanspeakershadmeanscoresof5.25atage3and15.25atage 5.Thus,themeandifferencebetweenthetwogroupsisnotably reduced,despiteaslightincreaseinthevariance.Withrespectto theinfluenceofSES,childrenwithhigherSESalreadyhadhigher numeracyscoresatthefirstassessment(b=0.13,p<0.05),andthe achievementgapwidenedoverthefollowingtwoyears(b=0.25, p<0.01).Model1explained27%ofthevarianceintheinterceptand 23%ofthevarianceintheslope;modelfitwasmoderatetogood (CFI=0.96,RMSEA=0.06).

InModels2aand2b,thetwoHLEindicatorswereincludedsepa- ratelyasadditionalpredictors.Theresultsshowedthatthequality ofthehomelearningenvironmentalreadyexplainedsubstantial varianceinnumeracyatthefirstassessment,whenchildrenwere onaverage3yearsold.TherewasnosignificanteffectofHLEon theslope,indicatingthattheearlyadvantagesofchildrenwitha high-qualityHLE weremaintainedoverthenexttwoyears.The coefficients (HLE-literacy:b=0.29, HLE-numeracy: b=0.14)also indicatethatthequalityofthehomeenvironmentintermsofpro- motingliteracyskills(numberofbooksinthehousehold,frequency ofactivitiessuchasreadingtothechild,etc.)wasmorestronglycor- relatedwithinitialnumeracyskillsthanwasthequalityofthehome environmentintermsofpromotingnumeracyskills(availabilityof gamesfacilitatinglearningnumbers,frequencyofactivitiessuchas counting,etc.).Severalpossibleexplanationsforthisrathercoun- terintuitivefindingareaddressedinSection4.

Afurtherresultworthnotingisthedecreaseintheinfluenceof familybackgroundfactorswhenhomelearningenvironmentwas includedinthemodel.ComparisonofModels2aand2bwithModel 1revealsthattheinfluencesofmaternaleducationallevelandSES ontheinterceptwereremarkablyreduced,suggestingthatpartbut notalloftherelationbetweenfamilybackgroundandnumeracyis

explainedbythequalityofthehomelearningenvironment.This Table2 Resultsoflatentgrowthcurveanalysespredictingthedevelopmentofnumeracyskillsfromthefirsttothethirdpointofmeasurement. PredictorsModel1Model2aModel2b InterceptSlopeInterceptSlopeInterceptSlope BSE(B)BSE(B)BSE(B)BSE(B)BSE(B)BSE(B) Childandfamilybackgroundfactors ####*#Ageatentrytothepreschoolsetting−0.120.060.140.08−0.110.060.150.08−0.140.070.130.08 ******Gender(0=female,1=male)−0.360.100.600.16−0.340.090.600.16−0.370.090.600.16 Parentalnativelanguagestatus(referencecategory:none) ***Oneparent−0.620.19−0.120.28−0.560.20−0.100.28−0.590.20−0.110.28 ******Bothparents−1.210.191.010.23−1.000.201.080.26−1.100.201.080.25 Mother’seducation(referencecategory:noqualificationsorvocational-trackqualification) *#Intermediate-trackqualification0.240.120.250.210.100.110.200.210.210.120.240.21 **Academic-trackqualification0.430.150.030.250.170.14−0.060.280.400.150.030.25 ***Anyotherqualification0.660.21−0.030.420.630.22−0.040.410.670.21−0.040.41 ***#*HighestSESofthefamily0.130.060.250.100.080.070.240.090.120.060.240.09 Homelearningenvironment(HLE) *HLE-literacy0.290.070.090.11 *HLE-numeracy0.140.050.090.09 SlopewithinterceptB=0.27SE=0.18B=0.27SE=0.19B=0.27SE=0.18 2******R0.270.230.330.240.290.24 CFI/RMSEA0.96/0.060.97/0.060.96/0.06 Note:Inallmodels,ageatassessmentwasincludedastime-varyingpredictor,althoughnotshowninthetable.Coefficientswerestandardizedusingthevariancesofthecontinuouslatentvariables(Std–standardization). *p<0.05. #p<0.10.

effectwasmorepronouncedforHLE-literacy,butwasalsoevident forHLE-numeracy.

3.3. Howdopreschoolstructuralandprocessquality characteristicsrelatetothedevelopmentofnumeracyskills?

(Models3,4a–d)

To examine the influence of preschool characteristics on earlynumeracy skillsand development,weaddedindicators of preschool experience to the growth models. Model 3 includes structuralcharacteristicsofthepreschoolaspotentialpredictors, controllingfor allchildandfamily backgroundfactorstested in Model1aswellasthetwoHLEindicators(literacyandnumer- acy).Theinclusionofstructuralcharacteristicsdidnotchangethe significanceofthepredictorsincludedinModel1.Hence,forrea- sonsofreadability,theyarenotshowninthefollowingtablesof results.ThefindingssummarizedinTable3indicatethattheaver- ageageoftheclass(b=0.13,p<0.01)andthesizeofthepreschool settinginm2perchild(b=0.13,p<0.01)werepositivelyrelatedto initialnumeracyskills.Child–staffratiowasnegativelyassociated withinitialnumeracyskills(b=−0.11,p<0.05),andtheproportion ofchildrenwhoseparentshadanativelanguageotherthanGer- manjustfailedtoreachstatisticalsignificance(b=−0.14,p=0.053).

Noneofthepreschoolstructuralcharacteristicsexaminedhadasig- nificantinfluenceontheslope,suggestingthatdifferencesdueto structuralcharacteristicsfoundatthefirstpointofmeasurement remainedstableoverthenexttwoyears.Model3explained38%of thevarianceintheinterceptand28%ofthevarianceintheslope;

modelfitwasmoderatetogood(CFI=0.96,RMSEA=0.06).

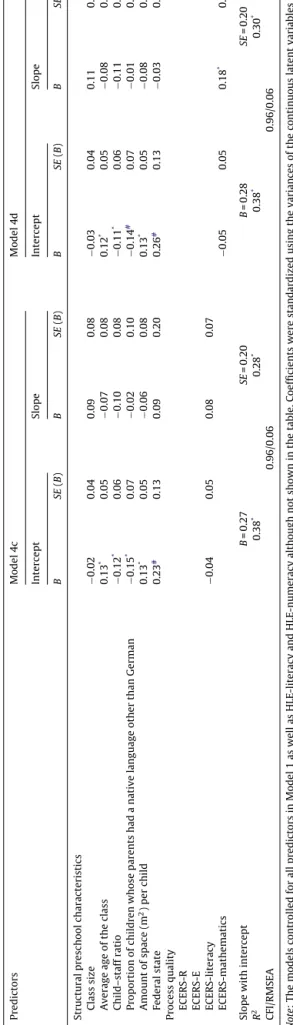

Models4a–dtestedtheinfluenceofindicatorsofprocessqual- ity. None of the indicators considered had a significant effect oninitial numeracy levels (see Tables 3 and 4).Global quality asmeasuredby theECERS-Rjust failedtoreachstatistical sig- nificance in its influence on growth over the preschool period (b=0.14,p=0.07).Inspectionofthequalityindicatorsthatreferred morecloselyrelatedtoeducationalaspectsrevealedthattheover- allECERS-E score wassignificantly related togrowth fromthe firsttothethirdassessment(b=0.15,p<0.05).ECERS-literacywas notrelatedtogrowth(b=0.08,p>0.05),butECERS-mathematics (b=0.18,p<0.05)hadthestrongestinfluenceongrowthoftheindi- catorsofprocessqualityexamined.ModelfitofModels4a–dwas satisfactory;allmodelsexplained38%ofvarianceoftheintercept, theamountofexplainedvarianceinthesloperangedbetween28%

and30%.

3.4. Doestheeffectofpreschoolprocessqualitydependonthe amountoftimethechildhasspentinthepreschoolsettingat studyentry?

We expected that children who had spent longer in the preschoolsettingatstudyentrywouldshowdifferencesinnumer- acy related to process quality at thefirst assessment, whereas childrenwithlesspreschoolexperienceatstudyentrywouldshow onlysmall quality-relateddifferences innumeracy. As wecon- trolledforageatassessmentinallmodels,theageatpreschool entryprovidesan indirectmeasureof theamountofpreschool experience at study entry. We therefore tested for interactive effectsofageatpreschoolentryandindicatorsofprocessquality.

Whentesting thesignificance oftheinteractionterms,wecon- trolledforallpredictorsusedinModel3(includingageatpreschool entry) and the relevant indicator of process quality (ECERS-R, ECERS-E, ECERS-literacy, ECERS-mathematics). Results showed thattheinteractions ECERS-R×ageat preschoolentry(b=0.19, p<0.01),ECERS-E×ageatpreschoolentry(b=0.16,p<0.05),and ECERS-mathematics×ageatpreschoolentry(b=0.38,p<0.05)had

asignificanteffectontheintercept. Inclusionoftheinteraction Table3 Resultsoflatentgrowthcurveanalysespredictingthedevelopmentofnumeracyskillsfromthefirsttothethirdpointofmeasurement. PredictorsModel3Model4aModel4b InterceptSlopeInterceptSlopeInterceptSlope BSE(B)BSE(B)BSE(B)BSE(B)BSE(B)BSE(B) Structuralpreschoolcharacteristics Classsize−0.020.040.080.08−0.020.050.110.07−0.020.040.110.07 ***Averageageoftheclass0.130.05−0.060.080.120.05−0.080.080.130.05−0.080.08 *#*Child–staffratio−0.110.06−0.120.08−0.110.06−0.090.08−0.120.06−0.090.08 ##*ProportionofchildrenwhoseparentshadanativelanguageotherthanGerman−0.140.07−0.040.10−0.130.080.010.10−0.140.07−0.020.10 2***Amountofspace(m)perchild0.130.05−0.050.080.120.05−0.100.070.140.05−0.090.07 ##Federalstate0.210.130.120.190.220.130.100.190.230.130.030.20 Processquality #ECERS-R0.020.070.140.08 *ECERS-E−0.030.060.150.07 ECERS-literacy ECERS-mathematics SlopewithinterceptB=0.27SE=0.19B=0.27SE=0.20B=0.28SE=0.20 2******R0.380.280.380.290.380.29 CFI/RMSEA0.96/0.060.96/0.060.96/0.06 Note:ThemodelscontrolledforallpredictorsinModel1aswellasHLE-literacyandHLE-numeracyalthoughnotshowninthetable.Coefficientswerestandardizedusingthevariancesofthecontinuouslatentvariables(Std– standardization). *p<0.05. #p<0.10.

Table4 Resultsoflatentgrowthcurveanalysespredictingthedevelopmentofnumeracyskillsfromthefirsttothethirdpointofmeasurement. PredictorsModel4cModel4d InterceptSlopeInterceptSlope BSE(B)BSE(B)BSE(B)BSE(B) Structuralpreschoolcharacteristics Classsize−0.020.040.090.08−0.030.040.110.07 Averageageoftheclass0.13*0.05−0.070.080.12*0.05−0.080.08 Child–staffratio−0.12*0.06−0.100.08−0.11*0.06−0.110.08 ProportionofchildrenwhoseparentshadanativelanguageotherthanGerman−0.15*0.07−0.020.10−0.14#0.07−0.010.10 Amountofspace(m2)perchild0.13*0.05−0.060.080.13*0.05−0.080.07 Federalstate0.23#0.130.090.200.26#0.13−0.030.20 Processquality ECERS-R ECERS-E ECERS-literacy−0.040.050.080.07 ECERS-mathematics−0.050.050.18*0.09 SlopewithinterceptB=0.27SE=0.20B=0.28SE=0.20 R20.38*0.28*0.38*0.30* CFI/RMSEA0.96/0.060.96/0.06 Note:ThemodelscontrolledforallpredictorsinModel1aswellasHLE-literacyandHLE-numeracyalthoughnotshowninthetable.Coefficientswerestandardizedusingthevariancesofthecontinuouslatentvariables(Std– standardization). *p<0.05. #p<0.10.

terms didnotchangethesignificance of anyof thechild,fam- ilybackgroundorpreschoolstructuralcharacteristics.Neitherdid it changethesignificance ofECERS-E,ECERS-literacy,or ECERS- mathematics.However,theeffectofECERS-Rontheslope,which justfailedtoreachthelevelofstatisticalsignificanceinModel4a, becamesignificant(b=0.16, p<0.05) whentheinteractionterm ECERS-R×ageatpreschoolentrywasaddedtothemodel.

Fig.2illustratestheinteractioneffectusingtheECERS-Escores.

Todisentangletheeffectsofageatassessmentandageatpreschool entry,andtofacilitateinterpretation,wepresenttherelationsfor thecohortofchildrenaged42–47monthsatthefirstassessment.

Thiscohort represents39.5% of thesample. Thecohort sample wasdividedintotwogroupsaccordingtoageatpreschoolentry (mediansplit).BasedontheECERS-Escores,wedividedthesam- pleintothreegroupsrepresentinglow-,medium-,andhigh-quality preschoolsettings.Thelow-qualityandhigh-qualitygroupscov- eredthetwoextremequartilesofthesample(representinghighest andlowest quality).Becauseof thesmallnumber ofpreschools withECERSscoresabove 5,we decidedtousea categorization basedonsamplestatisticstoillustratetheinteractiveeffect,rather thantheconventionalcategorizationasdefinedbytheauthorsof theinstrument(Sylvaetal.,2003).Fig.2presentsaverageinitial numeracyscoresforthesubgroups.Thefindingssuggestthathigh processqualityasreflectedbytheECERS-Escore,asopposedtolow ormediumquality,wasalreadyrelatedtohighernumeracyskills atthefirstmeasurementpoint.Thelongerthechildrenhadbeen inthespecificpreschoolatstudyentry,themorepronouncedthe effect.Inaddition,childrendidnotseemtobenefitfrommedium processquality(relativetolowquality)untiltheyhadspentacer- tainamountoftimeinpreschool.Thesignificantinteractioneffects ECERS-mathematics×ageatpreschoolentryandECERS-R×ageat preschoolentryreflectsimilarpatternsofresultsandcanbeinter- pretedinthesameway.

3.5. Istheeffectofpreschoolprocessqualitythesameamong childrenwithhomelearningenvironmentsofdifferentqualities?

We next sought to establish whether beneficial effects of preschoolprocessqualitydependedonthequalityofthehome learningenvironment.Tothisend,wecombinedthetwoHLEscales (literacyandnumeracy)toonemeasurerepresentingoverallqual- ityofHLE.TheinteractionECERS-E×HLEwastested,controlling forallchild,familybackground,andpreschoolstructuralfactors included Models1 and 3, overall quality of HLE, and ECERS-E.

The interactiveeffectproved to besignificantfor theintercept (b=0.87,p<0.05)andfortheslope(b=1.50,p<0.05).Theaddition oftheinteractiontermdidnotchangethesignificanceofanyof theeffectsreportedpreviously.Toillustratetheinteractiveeffect, weagaindividedthesampleintothreegroups,representinglow-, medium-,andhigh-qualityHLE.Again,thelow-qualityandhigh- qualitygroupscoveredthetwoextremequartilesofthesample.

Fig.3showsaveragenumeracyskillsatthefirstandthirdassess- mentforthesubgroupsofchildrenwhoattendedlow-,medium-, andhigh-qualitypreschoolandexperiencedlow-,medium-,and high-quality HLE. It shows that differences in numeracy at the firstmeasurementpointseemtobemainlyduetodifferencesin HLE, although children witha low-quality HLE didshowsmall quality-relateddifferences.Atthethirdmeasurementpoint,aver- agenumeracywashigherforallchildren,butespeciallyforthose childrenexposedtoamedium-orhigh-qualityHLE andahigh- qualitypreschool.Childrenwithamedium-qualityHLEseemedto benefitparticularlyfromahigh-qualitypreschool.However,Fig.3 also shows that children witha low-quality HLE didnot seem tobenefitfromthequalityofthepreschool.Thesefindingssug- gestthatatleastmediumsupportathomemaybenecessaryfor

4.3 4.4 4.4 5.3 5.2

6.3

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

high low

Arithmetic raw score at first assessment

low medium high Preschool quality

(ECERS-E)

Amount of preschool experience at study entry

Fig.2. Influenceofpreschoolquality(ECERS-E)onearlynumeracyskillsforchildrenwithdifferentamountsofpreschoolexperienceatthefirstassessment.

childrentotakeadvantageoftheopportunitiesforacademiclearn- ingofferedinpreschool.

4. Discussion

Thisstudy investigated the developmentof numeracy skills betweenage3and5yearsandprovidedinsightsintothepossi- bleinfluencesofchild andfamilybackgroundfactorsaswellas thehomeandpreschoollearningenvironmentsinGermany.Find- ingsonchildandfamilybackgroundfactorsrevealedthatgender, parentalnativelanguagestatus,maternaleducation,andSESwere associatedwithinitialnumeracy levelsaswellaswithgrowth.

Theseresultsreplicated thefindings ofotherstudies(e.g.,ECCE StudyGroup,1999;NICHDECCRN,2002a;Sammonsetal.,2004) andunderlinethatachievementdifferencesduetosocialandfam- ilybackgroundemergeveryearlyinchildren’slives.BothSESand parentalnativelanguagestatusindependentlypredictednumer- acyskillsatage3.Ontheonehand,theachievementgapbetween higherandlowerSESchildrenwidenedoverthepreschoolyears.

Ontheotherhand,childrenwhoseparentshadanativelanguage otherthanGerman—andespeciallythosechildrenwhoseparents

bothhadanativelanguageotherthanGerman—partlycaughtup bytheageof5years.Thisresultisparticularlyinteresting,because recentinternationalstudentachievementstudieshaveconsistently shownthatchildren’scognitiveoutcomesandeducationalcareers arefarmorestronglylinkedtotheiroriginandfamilybackgroundin Germanythaninothercountries(e.g.,OECD,2004a,2004b,2007).

Asaconsequence,expectationsregardingthepotentialbenefitsof preschooleducationareespeciallyhighforchildrenfromdisad- vantagedorimmigrantfamilies.Onepossibleexplanationforthe findingthatchildrenwhoseparentshaveanativelanguageother thanGermanseemtocatchupover thepreschoolyears isthat preschoolattendanceispreferentiallybeneficialforthisgroupof children.Unfortunately,thedesignofthepresentstudydoesnot includeacontrolgroupwithoutpreschoolexperience;therefore, thispossibleexplanationcannotbefurtherexploredwithinthis dataset.Itshouldalsotobementionedthatourresultsarebased solelyoncorrelationaldataandthereforedonotallowconclusions oncausesandeffectstobedrawn.

Withrespect tothequality of stimulation in numeracy and (pre)readingliteracy at home, ourfindings indicate—consistent with other research (e.g., LeFevre et al., 2009; Skwarchuk, 2009)—thatfamiliesengagein bothareas,butthat(pre)reading

3.4

14.7

3.9

13.7

4.4 5.24.9

14.9

4.8

15.3

5.7

15.3

6.1

16.4

6.0

14.0 14.8

16.4

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18

Arithmetic raw score

HLE medium HLE low

Preschool quality (ECERS-E)

low medium high HLE high

HLE medium HLE low

HLE high

t 1 t 3

Fig.3. Influenceofpreschoolquality(ECERS-E)onearlynumeracyskillsatthefirstandthirdassessmentforchildrenexposedtohomelearningenvironmentsofdiffering qualities.