Landscape Aesthetics

Theory and Practice of the Sensuous Cognition of Landscape Qualities

Lecture Script

PLUS Chair of Planning of Landscape and Urban Systems

Authors Rodewald, R., Hangartner M., Bögli, N., Sudau, M., Switalski, M., Grêt-Regamey, A.

Title Landscape Aesthetics: Theory and Practice of the Sensuous Cognition of Landscape Qualities – Lecture Script

Version First version

Institution PLUS – ETH Zurich

Location Zurich

Year 2020

Recommended Citation

IMPRESSUM

Unless otherwise specified, all images are the copyright of

© Archiv SL–FP

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Bettina Weibel and Reto Spielhofer for their great support and expert advice.

Contents i

List of Figures iii

1 Introduction 3

1.1 Prologue . . . . 3

1.2 The Landscape Model . . . . 4

1.3 Legal Basis . . . . 6

1.4 The Concept of Landscape . . . . 8

1.5 The Concept of Aesthetics . . . . 9

1.6 Perception . . . 10

1.6.1 More than a Look . . . 10

1.6.2 Triple Viewing . . . 11

1.6.3 Neuroaesthetics and Mindscapes . . . 13

1.6.4 Soundscapes . . . 15

2 Theories of Landscape Aesthetics 17 2.1 Object-related Perception . . . 18

2.1.1 Beauty as Objective Character . . . 18

2.2 Value Judgement . . . 20

2.2.1 Natural Beauty as Model for Arts . . . 20

2.2.2 Rule Based Aesthetics . . . 22

2.2.3 Beauty is Useful . . . 24

2.2.4 Habitat & Savanna Theory . . . 26

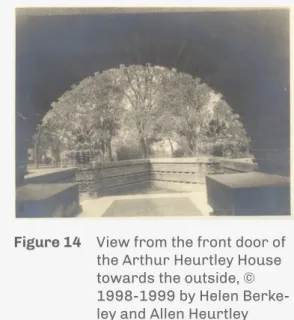

2.2.5 Prospect Refuge Theory . . . 28

2.3 Culture-related Perception . . . 30

2.3.1 Beauty as Cultural Construct . . . 30

2.4 Idealization . . . 32

2.4.1 Idealized Beauty . . . 32

2.4.2 Beauty as Common Sense . . . 35

2.4.3 Beauty as Illusionary and Arbitrary . . . 37

2.4.4 Beauty as Trigger for Sexual and Social Communication . . . 39

2.4.5 The New Sensuality . . . 41

2.4.6 Cultural Stability Theory . . . 43

2.4.7 Social Identity Theory . . . 45

2.4.8 Place Identity Theory . . . 47

2.5 Subject-related Perception . . . 49

2.5.1 Beauty as Subjective Experience . . . 49

2.6 Touch . . . 52

2.6.1 Atmospheres . . . 52

2.6.2 Identity Process Theory . . . 55

2.6.3 Information Processing Theory . . . 57

2.6.4 Attention Restoration Theory . . . 59

2.6.5 Stress Recovery Theory . . . 61

3 Significance for Practice – Further Reading 63

Contents

4 Becoming an Expert in Aesthetic Landscape Assessment 65

5 Testimonial 67

Reference Collection 69

Annex 75

Application on Cantonal Level . . . 75

Application on Local Level . . . 80

Application on Project Level . . . 86

Timeline . . . 89

1 Conceptual Model of Landscape . . . . 5

2 The Gonerli Cascades in Oberwald VS . . . . 7

3 Rabbit and Duck . . . 12

4 Attractive pathways invite us to walk . . . 13

5 Sound Inventory in Parc Naturel . . . 15

6 Model of Landscape Aesthetics . . . 17

7 Object-related Perception . . . 18

8 The Sils lake as a touristic hotspot . . . 19

9 Value Judgement . . . 20

10 The Ermitage in Arlesheim . . . 21

11 Linear alleys in Val de Ruz . . . 23

12 New lake in Liebefeld . . . 25

13 Partially reforested landscape in Thal SO . . . 27

14 View from the front door of the Arthur Heurtley House towards the outside . . . 29

15 Culture-related Perception . . . 30

16 Making shingles for shingle roofs in Safiental GR . . . 31

17 Idealization . . . 32

18 The ideal of a beautiful alpine agricultural landscape . . . 34

19 Recovered vineyard in Zeneggen VS . . . 36

20 Toboggan run in Bernese Oberland . . . 38

21 Single-family houses shaped by individual taste . . . 40

22 Former cement plant integrated in a parc . . . 42

23 Länggasse in the city Berne . . . 44

24 Demonstration in Zurich . . . 46

25 Subject-related Perception . . . 49

26 Waterfall (Jaun pass, FR) . . . 51

27 Touch . . . 52

28 Chichacher – a green area close to the church of Tenniken BL . . . 53

29 Monumental tree in the Saanetal FR . . . 56

30 ThePreference Matrixby S. and R. Kaplan . . . 57

31 Asher Brown Durand – Kindred Spirits . . . 58

32 The therapy garden of the RehaClinic in Bad Zurzach . . . 60

33 The Central Park in New York City . . . 62

i Fuzzy Cloud map of the identified 26 diverse landscape types . . . 76

ii Determined kea Ares in the canton Schwyz . . . 77

iii The six identified key areas . . . 78

iv The ancient monastery of Schönthal . . . 80

v Subspace aesthetics of the monastery of Schönthal . . . 84

vi Addition of an existing wall . . . 85

vii Addition of an existing wall . . . 85

viii The Modification of the landscapes as Example in two out of seven scenes . . . 86

ix The Modification of the landscapes as Example in two out of seven scenes . . . 87

x Sensors to measure the change in skin conductance . . . 88

xi Overview of the Theories of Landscape Aesthetics . . . 89

1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Prologue

“A science, which renounces appearances, can only aim at their destruction..."

—Giorgio Agamben, Che cos’è la filosofia, 2016

"There’s no accounting for taste". This popular idiom, arising probably in the middle age, declares our aesthetic judgment as purely subjective and not objective. Everyone, so the common opinion, has his or her own sense of taste, leaving no space for discussion. However, the more than 2500 years old history of the philosophy of beauty reveals that our judgement of beauty has besides its subjective part also an important public and objective dimension, anchored also in law (in Switzerland since 1907) and in the European Landscape Convention from 20001. As we go on, we will actually see that the introductory phrase is not helpful at all in explaining why many people demand landscape protection or why aesthetic values are included in the major reports of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment2. How do we – as landscape planners and experts in sustainable development – gain the ability to evaluate landscape qualities and to conceive spaces so that they produce commonly appreciated aesthetic values?

In addition to the classical descriptive categories of landscape analysis, which concern geomor- phology, ecological functions, history and land use patterns, the new categorylandscape aesthetics emerges. Public acceptance of new technologies or management systems such assmart homesde- pend on people’s sensual-emotional potential. Crucially, it is these aspects of sensitivity, which enable an empathetic view on our landscapes and their development. Once people’s understanding of aes- thetic qualities are better, complex negotiation processes will result in more sustainable and satisfy- ing outcomes. Unfortunately, we cannot ask the trees and the soil if a new building or other changes seem acceptable to them in their landscape.

This script will give an introduction into the main categories of landscape aesthetics starting from the legal basis and the common definitions, passing the main concepts of beauty and the establishment of preferences. The script will conclude with practical applications. The main objective is to help un- derstanding the important role of aesthetic aspects in the evaluation of landscapes and for specific questions of landscape management. Students become acquainted with the aesthetic experiences of landscape enabling them to recognize and implement aesthetic goals for landscape planning.

Knowledge of landscape aesthetics, often neglected in practice, helps to address aesthetic feelings into a communicable form in order to better understand people’s emotions and expectations regard- ing transformation processes of landscapes.

Raimund Rodewald

1https://www.coe.int/en/web/landscape

1.2 The Landscape Model

The concept of landscape is the result of a coincidence of factors objectively describing the form of space, socio-cultural imprints (e.g. economic processes), and aesthetic experiences. The concept of landscape has thus evolved and is understood nowadays as a dynamic concept differing between individuals depending on their experiences and preferences. Looking at the past, some ideas and con- cepts of landscape became quite famous. The bible for example, describes landscape as the good land with rivers and distant mountains, fertile fields and fruit trees without ever mentioning pastures. This could reflect the act of humans settling down, becoming dwellers after years of nomadic life.

However, already ancient Greek philosophers presented a first notion of landscape, referred to as the charming place by Plato and later in the roman period aslocus amoenus. Poets such as Theocritus, Vergil and Sannazaro promoted the concept ofArcadiaas a kind of a (non-biblical) paradise place bet- ter described as an idyll, where shepherds, nymphs, and many wild animals live together in a bucolic scenery of flowering meadows, woods, rivers with sufficient food for everyone, in an eternal spring atmosphere.Arcadiahas become for hundreds of years the main ideal of a life immersed in peaceful nature, where property and power do not exist, replaced by poetry and music. Jacopo Sannazaro in 1504 conceivedArcadiaas an antithesis to the town. The notion of landscape hence existed much longer before its term!

In western civilization, the notion of landscape as a term is born only in the Renaissance period (late 15thcentury). Its origin is referred to the early landscape painters, like the Flemish Jan van Eyck, the German Albrecht Dürer or Italian painters like Jacopo and Giovanni Bellini, Giorgione, Titian and oth- ers.

In China, the notion of landscape connecting the objective reality of nature with the subjectively expe- rienced emotion has already been known (asShanshui) 1000 years earlier than in Europe.

However, the interaction between nature and human goes even further back in time. Proof thereof are cultural expressions of human-nature-relations such as the strange Nazca Lines in found in a desert in southern Peru. Other examples are the dreaming-tracks of the Aborigines or the Kailash Mountain of Tibetan Buddhists representing a kind of a natural mandala. Both, the detached outsider (e.g. city dwellers), and the existential insider (e.g. local people living close to nature and natural hazards), are enabled to have an aesthetic view on landscapes which requires a certain distance to everyday life.

In recent times, land-artists like Richard Long, Andy Goldsworthy or the Swiss Martin Stützle com- bined their interventions strongly with specific natural phenomena. Currently, landscape represen- tations in artworks have again become a matter of interest in the broad public, expressing current social and political issues.

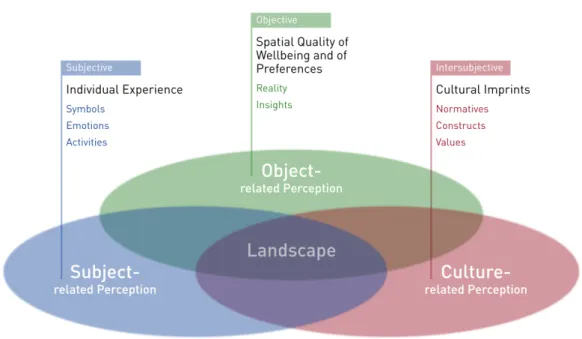

In the year 2000, the European Landscape Convention (ELC, 2000) has given a commonly valid defini- tion of landscape: “Landscape means an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors". Landscape is, therefore, an issue of per- ception and its interrelation between the objective spatial quality. Figure 1 shows a conceptual model of landscape grounded on the ELC-definition. Therefore, each area, inside as well as outside of ur- banized sites, become landscape as term when its spatial factors like natural or man-made elements are subjectively, objectively or culturally adopted by our perception and embedded in a varied man- ner into our being and vice versa. Theconceptual modelof landscape includesindividualexperience, comprising symbols, emotions and activities (like the wish to hike a newly discovered trail through an alpine meadow),spatial qualityof wellbeing and preferences which deliver reality and insights and cultural imprintsas well as norms, (social) constructs and values, which for example manifest in com-

1.2. The Landscape Model

monly shared place identities. This model allows us to group the numerous theories of beauty and of landscape preferences (see chapter 2).

Figure 1 Conceptual model, presenting landscape as interface of subjective, objective and culture- related perception. The model is based on the landscape-definition from the European Landscape Convention (ELC, 2000) (graphics by ETHZ/PLUS).

In addition, the English notion oflandscapedistinguishes place characteristics (thereality) and peo- ple’s imprints like land-use or ownership, as well as perceptual and aesthetic aspects (Tudor, 2014).

The English approach is therefore coherent with our conceptual model of landscape used for this lecture.

Conclusion

I Landscape is a perceptual phenomenon

I The actual definition of landscape given by the ELC is holistic and covers all spaces

I Landscape is not only an affair of detached outsiders who aren’t dependent on nature anymore. In addition, existential insiders, like farmers, are enabled to consider their spaces as landscapes

1.3 Legal Basis

In recent time, aesthetics has become an important topic of spatial planning, land management, and participation processes. Inevitable changes of a landscape can generate strong oppositions within local actors, as they directly influence the perceived environment and effects become visible to the people. Economic change, new technologies, climate change, demographic development as well as po- litical decisions have strong effects on landscapes. Being aware of the risk of mutilation of our Swiss landscapes, analogue to many other countries, Swiss politics have recognized the importance of main- taining the beauty of landscapes, and protect, preserve and improve sites of local character asepit- omeof a national identity with different tools, measures and instruments.

The Swiss Civil Code (Schweizerisches Zivilgesetzbuch) from 1907 contains the permission for the cantons to “impose restrictions on ownership that are in the public interest, and in particular that relate to (...) conservation of antiquities and natural monuments, preservation of areas of natural beauty and scenic vantage points and protection of mineral springs." (article 702).

The Federal Act on the utilization of hydro power (Bundesgesetz über die Nutzbarmachung der Wasserkräfte), enforced in 1916, includes article 22, which is entitled as “Preserving the beauty of the landscape". This article requests that “natural beauties must be protected and preserved undiminished where the general interest in them prevails", and that “hydroelectric power plants must be constructed in such a way that they do not disturb the landscape or disturb it as little as possible."

In later years, the legal requirement for protecting landscapes including cultural monuments and important sites of local character and historic sites has been adopted, extended, and reinforced.

The Federal Act on the Protection of Nature and CulturalHeritage (Bundesgesetz über den Natur- und Heimatschutz) from 1966 requires in article 3 (obligations) that:

I In the fulfilment of federal tasks, the Confederation, its institutions and enterprises, and the cantons shall ensure that heritage landscapes and sites of local character, historical sites, and natural and cultural monuments are carefully managed and, where there is an overriding public interest, preserved undiminished.

I They shall fulfill this obligation by suitably designing and maintaining their own buildings and instal- lations, or by foregoing their construction altogether (...);

The Federal Act on Spatial Planning (Bundesgesetz über die Raumplanung) from 1979 determines in article 3 (Planning Principles) that the authorities responsible for planning tasks pay attention to the following principles:

I The landscape is to be taken care of. In particular:

I Settlements, buildings, and installations have to fit into the landscape;

I Near-natural landscapes and recreation areas should be conserved

1.3. Legal Basis

The cantons are bound by the spatial planning law to identify within their structure plans (Richtpläne), which landscapes are of special beauty, valuable or important for recreation, and as natural habitats.

Based on the legal conditions of the comprehensive balancing of interests, the administrations of all levels have to weigh for each of their planning decisions, the full interests of protection and use in each single case; most notably, this happens not only within, but also outside of such protected sites (Article 3 of the Ordinance of the Federal Act on Spatial Planning).

An important international step was the ratification of the European Landscape Convention (ELC) from 2000 by the Swiss Parliament (effective since June 2013). The ELC not only provides a clear and gen- erally valid definition oflandscape, but requires an identification, assessment, and definition of land- scape quality objectives of all landscapes throughout the whole territory (Article 6). The law requires the involvement of the relatively affected population.

Thanks to these legal bases there is an increasing need for expert knowledge on characteristics, eco- logical, economic, social, and cultural values (measurable e.g. ecosystem services), especially includ- ing aesthetics of landscape. Landscape aesthetics have become a public affair bridging between ex- pert opinion and the affection of the population. In many conflict situations between use and protection, the aesthetic argument is the most conflicting one. Therefore, we need assessment methodologies and practical experiences to grasp the spatial aesthetic qualities and potentials in urban, rural, and natural areas for a better implementation of the laws.

Significance in Practice Aesthetics in Court Judgements

Figure 2 The Gonerli Cascades in Oberwald VS

Oberwald: Hydropower plant project: The Swiss Federal Supreme Court stated in a judicial decision 2014: “In the present case, the Gonerli water in particular has outstand- ing landscape features worthy of protection. It is located in a small side valley that is still completely untouched to- day and is visible from far away. A balancing of all interests shows that the catchment of the Gonerli water would rep- resent an unjustifiable impact on the landscape in view of the low benefit of the power plant for the Swiss energy sup- ply" (BGE 140 II 262).

Conclusion

I During the implementation of planning laws, aesthetics is of great importance, but they are often neglected.

I Within the comprehensive balancing of interests, the topiclandscapemust be dealt with in a pro- fessional and responsible-minded fashion.

I Expert reporting by concerned offices or by commissions (national commission for nature and land- scape protection and monument conservation (ENHK, EKD) or cantonal/local commissions) are in- dispensable.

I Characteristics like protected sites, impact in a formerly untouched area, visibility of the impact, and closeness to nature or wilderness are decisive.

1.4 The Concept of Landscape

The terms space, land and environment imply an important difference to the terms landscape and place. Linguistically the general meaning ofspacein a purely geometrical or physical sense reflects the fundamental disconnection between object and subject. In the following, we explain how the mean- ing oflandscape(andplace) combines human’s perception with the presumably objective reality. Thus, the concept of landscape can be described as a perceptual model.

The concept ofspacehas a long and intricate history (see section 1.2). The Euclidean geometry and classical mechanics have dominated the spatial concept as a mainly visual space, ending up in the concept ofabsolute spaceby Newton. Immanuel Kant introduced thesubjectivityof space as visual form (Anschauungsform). Every species has, thanks to its senses, a specific perception of space, hence forming each its particular environment. The termspacewas discussed in cultural sciences, too, wherespacehas been considered asprimalsymbol of a culture (Ursymboleiner Kultur, Spen- gler (1920)). According to Spengler, the antique culture regarded space as aspaceof touch, what he calledapollonian, whereas in modern times space was considered as unlimited and expanded, where all borders can be crossed by means of our technological progresses (Faustian). In the middle of the 20th century, space was commonly considered from a purely environmental perspective, distin- guishing living space, ecosystems, habitats, natural environment, and co-space (Mitwelt). Finally, the today’s psychologically and sociologically dominated concept of landscape emerges as anemotional andsynaesthetic(including different sensual experiences at one) space. This comprises cultural and social aspects described by various theories, such as: Sense of Place, Place Identity, Place Attachment, as well as virtual spaces (e.g. like bubbles).

Conclusion

I The original term of the Newton space has been subjectified since the 18thcentury.

I Today’s understanding of landscape is derived from a concept of space that includes social, cultural, synaesthetic and emotional components.

1.5. The Concept of Aesthetics

1.5 The Concept of Aesthetics

Similar to the concept oflandscape, the concept ofaestheticshas evolved over time. Its notion has dif- ferent aspects and is present in our daily lives (for example in architecture or fashion). Everyone has a connection to aesthetics. There are certain things we intuitively like or dislike due to their appearance or taste. However, these preferences are sometimes difficult to describe with words.

There is an important difference between the original Greek term ofaisthesisand the currently used aesthetics. The first can be conceived as theTheory of the Sensual Perception. In antiquity,sensual perception mainly served the purpose to form our reason and to gain knowledge about a good and virtuous life.

However, a single sense for (landscape) beauty does not exist (even though some philosophers of an- tiquity believed so). Thus, we can assume that synaesthetic experiences like visual and acoustic ex- periences, and in minor importance olfactory, taste and touch experiences areworking together. In antiquity, the meaning of the perception of the reality was closely linked to beauty. Thesensualpercep- tion served in distinguishing the pure and true beauty from the imitating and deceiving appearances.

If the reality contained and expressed the essence of the truth and the good it was always consid- ered as beautiful, whilelook-a-like’s, fake things, and incidents could never be regarded as beautiful.

Hence, aesthesis considers always both parts of subjective and objective perception. However, this idealized double character of aesthetics in the broader meaning of aesthesis, including epistemologi- cally important objective aspects, as well as emotional, contemplative and hedonistic subjective parts, has been since the antiquity changed. In artistic trends like Impressionism, Expressionism or Post- modernism, aesthetic perception primarily focuses on subjectivity, more or less independent of the objective reality.

Unlikeaisthesisthe termaestheticsis today commonly understood as theTheory of the Beauty(as an objective quality of things), the artwork’s beauty, theory of the philosophy of arts but sometimes also in the enlarged meaning of theTheory of Perception.

A further difference of meaning has to be clarified: according to Immanuel Kant, we should distinguish taste from the judgment of beauty.

The first is conceived as a subjective personalstatement: if something is beautiful or not is bound to a sensation of pleasure, which does not concern primarily the object, but rather the subject in satisfying our senses. Whereas the judgment of beauty asks for reflections, concepts, theories, and rules, which explain, why something is perceived or considered as beautiful (or “aesthetical"). Beauty and aesthetics are a public and somehow objectivejudgement, which is based on afree playbetween intellect and communicable aesthetic experience.

In practice, this understanding of the equivalence of subjectivity and objectivity in the aesthetic dis- course opens the way for participation processes in landscape development (see chapter 3).

Conclusion

I There is a double character of the meaning of aesthetics with regard to the old Greek term aisthesis.

I Using the term of aestheticswe need to differentiate between (subjective-related) emotion and (objective-related) perception.

I Landscape aestheticscan be defined as the sensual experience of landscapes.

1.6 Perception

“All real life is encounter"

—Martin Buber, 1923

“People know that they could not have a neutral relationship to buildings and music"

—Peter Sloterdijk, 2007

1.6.1 More than a Look

The perception of a landscape is a quite complex process. What do we exactly do when we perceive a place with our senses? Is it a passive or active process? What exactly happens when sensual stim- ulation and our responses like emotion, interpretation, classification and judgment interact? Are we aware of each single step of the perception, and do we have the necessary language to describe the aesthetic qualities of a place?

Kevin Lynch, American architect of the 1960s, usedwalksin order to study the role of the environ- mental image of urban life. These so calledperceptionwalks originally were a method of ethnological researchers. German urban researcher Anke Rees (2016) used the method ofperception walksto explore the effects of buildings on people living in the neighbourhood.

The perception walk is a sensual exploration of a place, a building and/or a landscape to grasp the qualities of atmospheres in a conceptual way, even though a place is not “talking" to us directly. At- mospheres arise from the presence of elements, structures, arrangements, colours and sounds. The objective is to analyze the meaning and atmosphere of a place, which arise due to inner images and emotions that are transmitted from the place. A result might be a fact sheet with a description of the aesthetic experiences structured by atmospheres.

The perception walk is, therefore, a method enabling to have an active empathic look on a place even when it is at the first glance ordinary and common in order to understand the missing language of a place.

Significance in Practice Perception Walk

The walk allows a systematical exploration of a place and the mapping of the subjective ex- periences. It can be performed individually or in groups. The following atmospheres accord- ing to the work of Anke Rees (2016) are helpful to track possible attributions in a polarized way (e.g. cold-warm, living-dead) that the walker(s) can experience.

I Atmosphere of the Boldness – What is provoking/innovating?

I Atmosphere of the Living – What is identifying, affecting (pleasure, sensual, exotic, familiar)?

I Atmosphere of the Emptiness – What is passing, reminding?

I Atmosphere of the Bleakness – What is given up, abandoned, sad, disturbing, a non-place- like?

I Atmosphere of the Mystery – What is enigmatic, suggestive, interesting for further ex- ploration?

Literature

Rees, A. (2016).Das Gebäude als Akteur: Architekturen und ihre Atmosphären, Band 5 in:Kulturwis- senschaftliche Technikforschung. Chronos, Zürich.

1.6. Perception

1.6.2 Triple Viewing

Our viewingin everyday life is almost reduced to an informative view due to a quick and cursory glimpse. Information processing is the main purpose of this first view. As a result of our accelerated life, landscape is threatened to get lost in mind and senses and thus evaporates. Contemporary land- scape is therefore often the final product of a generalized visual numbness and neglecting of place identity qualities.

Knowing how people look at things (what we capture first, where we first look at) is a very valuable information. Think about where things are placed in the supermarket (not too high, not too low, in the center) or how websites are designed, but also how cities are created (e.g. landmarks such as churches) and gardens are designed. There are various concepts distinguishing atriple-layerof our visual perception, theTriple Viewing: Evolutionary history (human as a relatively unprotected savan- nah being) explains that thefirst visionserves the rapid transmission of information – the reading of a landscape. Here, the question “Where is the what?", is paramount.

With thesecond vision, we absorb the colors and forms - the aesthetic stimuli. This gives place its special atmospheric appearance. With thethird vision, we then symbolize and identify with our pre- conceived constructs, images, preferences, values, and individual attributions of signs and symbols.

Lucius Burckhardt (1979)

The Davos-born sociologist Lucius Burckhardt spoke of three layers from which a landscape is built up within us Burckhardt (2006): A first layer of the mere appearance of colors and structures, the informative view, a second layer of the beginning recognition of natural and productive-technical con- nections, thesensual view, and a third layer in which social attributions and thus the dimension of time becomes visible, theassociative view. In the temporality of a landscape lies its change and this leads to the fact that we always arrive too late in the intact landscape in the sense of a charming place (Locus amoenus).

Christophe Girot /Sabine Wolf (2010)

The research work of the MediaLab of ETH Zurich3offered a summary entitledLandscapeVideo, pub- lished in 2010 in the form of an exhibition, publication, and video. In the videos, a consolidation of fragmented spaces into a complex unit allows a systematization of the visual experience. The authors distinguished three main visual experiences: Firstly, an analytical gaze is defined, which is character- ized by a certain distance and a cautious survey of the space, a physical gaze describing the imme- diate physical and emotional experience (forms, bodies, colours), as well as a poetic gaze which link the things together to something new, in symbolizing and composing them and coming closer to the atmospheres of a space).

Erwin Panofsky (1939)

Panofsky, a German and American art historian, gained particular prominence for his studies in iconography (the study of symbols and themes in works of art). For Panofsky, a work of art could be understood to form a visual language. Panofsky stated that the pre-iconographical description aimed to formalizing objects and events on a painting. The second layer was called the iconographical analy- sis, which requiredknowledgeof literature-based basic meanings and concepts. The highest level of visual interpretation is the iconological interpretation to record the specific symbolic content and the intrinsic meaning of the painter and the painting with regard to the history, the politics and available technologies.

Significance in Practice Difference of Recognizable and Seeing View

Figure 3 Rabbit and Duck, (Jastrow, 1899)

The art theoretician Max Imdahl (Majetschak, 2007, p. 158ff) explained with the seeing view, as opposed to the recognizable view, the kind of perception which deals with the effect of the picture and not with the recognizable object of the picture. This would pre- vent from new experiences (see Figure 3) and create a dogma for landscape shaping. In practice, we should not transfer preconceived aesthetic judgments and recipes from one place to the other. Rather, design options and architectural solutions must be tailored to each individual case in order to take sufficient ac- count of the different landscape qualities

Literature

Burckhardt, L. (2006).Warum ist Landschaft schön? Die Spaziergangswissenschaft. Martin Schmitz Verlag, Berlin.

Girot, C. and Wolf, S. (2010). Cadrages II: Blicklandschaften, Landschaft in Bewegung : landscapev- ideo, landscape in movement.

Jastrow, J. (1899). The Mind’s Eye.Popular Science Monthly, 54, 299 – 312.

Majetschak, S. (2007). Ästhetik zur Einführung, Band 334 in:Zur Einführung. Junius, Hamburg.

Panofsky, E. (1939).Iconology. Oxford University Press, New York.

1.6. Perception

1.6.3 Neuroaesthetics and Mindscapes

Neurobiologist Semir Zeki first describedneuroaestheticsin 1993. His studies are dedicated to the neural basis of aesthetic appreciation of art, suggesting that one can determine what a person finds beautiful by examining a specific area of the brain, namely the medial orbitofrontal cortex (mOFC). Fol- lowing Zeki there is an abstract quality to beauty according to which the perceived beauty does not have to be tied to any particular medium. If you experience a face or a landscape as beautiful, activity in the mOFC can be observed. However, recent studies4revealed that such activities and experiences are not related with only one single brain region or hemisphere. They emerge from the interaction of activity taking place in many different brain regions. Interestingly, parts of the motoric system are also engaged if people look at paintings, which depict actions.

Gibson (1979) derived from these findings thecharactersofperceivedthings, which evoke appropri- ate actions, so-called affordances (Leistungserbringung). Mirror neurons allow the response to the execution and perception of actions (Kilner et al., 2009). These brain cells designated for social interac- tions and empathy, provide some kind of inner embodied imitation of the actions of other people, which in turn ‘simulate’ the intentions and emotions associated with those actions. Hence, we can assume a multimodal nature of perception (limbic,sensomotoric).

Mindscapeis the landscape of our mind, contrasting the external reality with an internal, imagined reality. Internal reality means consciousness or states of mind, for example, the aesthetic experience of a river and the associations it involves. Inner reality is subjective. It exists in the minds of the sub- jects only and it is a topic of psychologists and psychoanalysts.

French psychoanalyst Jean-Bertrand Pontalis summarized: “To have any hope of being ourselves, we must have many places inside of us" (Lingiardi, 2017, p.15). According to English psychoanalyst Don- ald W. Winnicott transitional objects and phenomena (as collected objects) are unspectacular objects, which characterize the mental and emotional appropriation of the outer reality (Lingiardi, 2017, p.43f).

With regard to landscapes, examples are: picking up shells on a beach, picking flowers, or small stones in a riverbed.

Significance in Practice Resonance between Landscape and Actions

Figure 4 Attractive pathways invite us to walk

Neuroaesthetic findings explain why landscapes evoke in us the motivation for specific actions. At- tractive pathways, evaluated as appropriate, in a landscape open our desire to walk; non-attractive pathways evoke the opposite. There are hence, direct effects of landscapes on our wellbeing, our identification and our actions of life.

Conclusion

I Neuroaesthetics deals with the neural basis of aesthetic experience of art works.

I There is a multimodal nature of perception.

I There is an embodied simulation by mirror neurons leading to a syntonic accord between the ob- server (subject) and the observed (object).

Literature

Gibson, J. J. (1979).The ecological approach to visual perception. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Kilner, J. M., Neal, A., Weiskopf, N., Friston, K. J., and Frith, C. D. (2009). Evidence of mirror neurons in human inferior frontal gyrus.Journal of Neuroscience, 29(32), doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2668–

09.2009.

Lingiardi, V. (2017).Mindscapes: psiche nel paesaggio. Raffaello Cortina, Milano.

Zeki, S. (1993).A vision of the brain. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford.

1.6. Perception

1.6.4 Soundscapes

Rachel Carson’s “Silent spring" (1962) was one of the first indictments against the pesticide use in agriculture in the U.S. Silence was the sign for the death of nature. In 1977, the Canadian composer Raymond Murray Schafer introduced the concept ofsoundscape(Klanglandschaft), consisting of the entire acoustic environmental structure – whether urban or rural; man-made or wild.soundscapes allow us to attentively hear the character, complexity, and the changes of the acoustic reality. The combination of sounds made by humans, animals or weather, amplified and modified by the acoustic properties of the wider landscape, are resulting in a characteristic acoustic footprint, orsoundscape, of each landscape. In recent time, musicians also apply soundscapes by arranging environmental sounds into musical compositions.

In general, the acoustic sense is a sense for the perception of spatiality, and vice versa, space is needed to generate sounds. In the Renaissance parks have been created by architects also for special acoustic experiences.Soundscapesare therefore the (musical) space formed around a sound (Rode- wald, 1999, p. 150f). Analog tolandmarks(characteristic attributes in a landscape) sounds which are unique and possess qualities that make them specifically recognizable by the people, are calledsound- marks.

Bernese composer Peter Streiff (2016, p. 50ff) studied aesthetic experiences of participants of acous- tic walks – some events on behalf of the Swiss Foundation for Landscape Conservation. During these walks Streiff asked to describe the characteristics of the acoustic environment, e.g. the existence of melodies, rhythms or compositions.

Significance in Practice Identification of Sound Characteristics

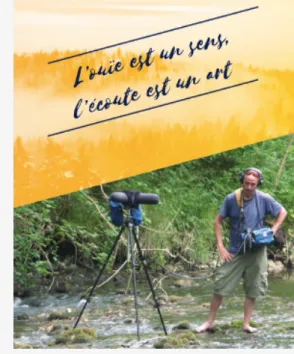

Figure 5 Sound Inventory in Parc Na- turel

Nowadays, environmental sounds are often reduced to noise barrier problem and the missing silence.

The qualities between noise and silence often mark places. For example, the imagination of Naples is also bound to an acoustic imagination of the Vespa motors in the narrow streets mixed with the singing women out of the windows and some crying market sellers.

Whereas the village of Vrin in Lugnez Valley is marked by the bleating of the sheep passing in midst the vil- lage.

The Parc Naturel régional Haut-Jura/F elaborated an inventory of the audible points and specific acoustic sites in 1989. Each place has its acoustic signature thanks to their spatial arrangements of sound ampli- fying or absorbing elements. This knowledge should enter also in the planning of urban leisure areas like parks

Literature

AudioVisual Lab ETH (ed.) (2020). A surround system for spatial audio-visual simulation of land- scape scenarios. https://plus.ethz.ch/de/forschung/lvml/audio-visual-lab.html (accessed:

June 2020).

Bosshard, A. (2020). Soundcity. http://www.soundcity.ws/aros/ (accessed: May 2020).

Carson, R. (1962).Silent spring. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston.

Gantenbein, K. and Rodewald, R. (2016). Arkadien: Landschaften poetisch gestalten. Edition Hoch- parterre, Zürich.

Schafer, R. M. (1977). The soundscape: our sonic environment and the tuning of the world. Destiny Books Rochester, Vermont.

Schütz, N. (2016). Arkadien bedenken – Klanglandschaft gestalten. In: Gantenbein, K. and Rodewald, R., (ed.),Arkadien: Landschaften poetisch gestalten, 60 – 71. Edition Hochparterre, 1. Auflage, Zürich.

Schütz, N. (2020). Echora.https://www.echora.ch (accessed: May 2020).

Rodewald, R. (1999). Sehnsucht Landschaft: Landschaftsgestaltung unter ästhetischem Gesicht- spunkt. Chronos, Zürich.

Streiff, P. (2016). Landschaften hören. In: Gantenbein, K. and Rodewald, R., (ed.),Arkadien: Land- schaften poetisch gestalten, 50 – 59. Edition Hochparterre, Zürich.

2

THEORIES OF LANDSCAPE AESTHETICS

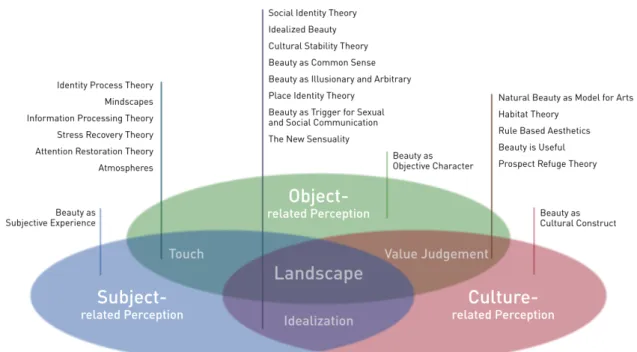

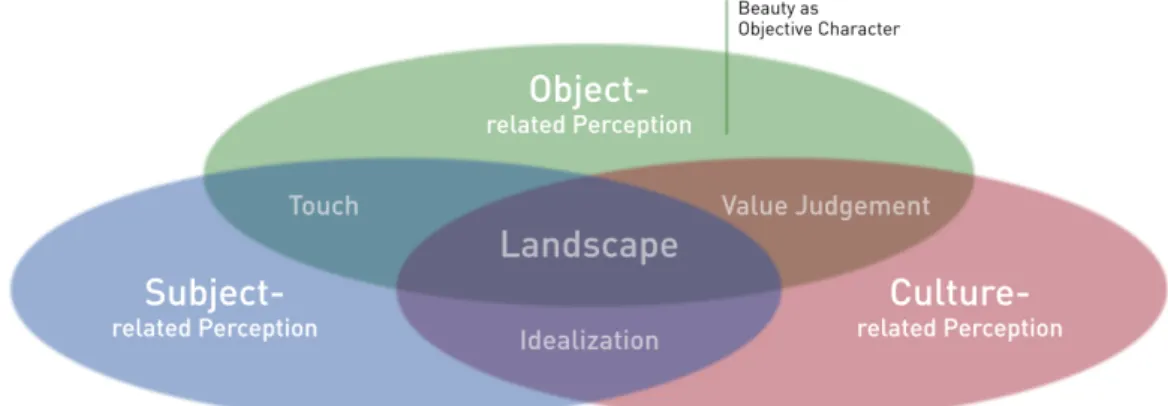

As described in section 1.4 The Concept of Landscape the termlandscapeis understood based on the definition of the ELC. Figure 6 illustrates the three important dimensions, which all influence the perception of landscape: theobject-related, theculture-relatedand thesubject-relatedperception.

However, these dimensions cannot always be distinguished clearly from one another but rather com- plement human’s perception of landscape. Therefore, subdimensions have been established for over- lapping parts:Value Judgment,IdealizationandTouch. In the following chapter, different theories and concepts about landscape aesthetics assigned to the dimensions and subdimensions of the model are presented.

Alle these theories and concepts have emerged in different times or have even evolved over several time periods. In order to give a chronological overview a timeline has been established and can be found in the Annex.

Figure 6 Model of Landscape Aesthetics

Legend

2.1 Object-related Perception

The object-related perception presumes that landscape is perceived and valuated only by its objective content. Hence, neither cultural background nor subjective experience would play a role in landscape perception and a general accordance among individuals would be the outcome.

Figure 7 Object-related Perception

2.1.1 Beauty as Objective Character

Main characteristics

Immanuel Kant, Martin Seel, Beatrix Sitter-Liver, John Berger

16thcentury, present times

Ethics, ecological aesthetics, tourism and poetry

In Kant’s opinion, the aesthetic view of nature cannot be based on theoretical-objective concepts ((Ginsborg, 2019, p. 10f), see also section 2.5). The aesthetic perception of the nature needs therefore a distance and an absence of practical and theoretical interests. From forms and colors for example, an objective perception can be derived but not from beauty. Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten’s attempt to prove objectively the rules of beauty in the 18thcentury was criticized by Kant. However, also Kant claimed a universal agreement for the judgments of taste. Elsewhere Kant used the famous sentence

“beautiful things indicate that man fits into the world" (die schönen Dinge zeigen an, dass der Mensch in die Welt passt) to express the awareness to be really in the world of objective things that we per- ceive and value as beautiful, and not only by means of their forms and colors. This gives us certainty to be in harmony with and inside (and not outside) the world.

2.1. Object-related Perception

Ethical thinking is also related to the experience of beauty in the philosophy of Kant, attributing ab- solute (inner) values to all beings like humans, animals and plants (extendable also to pure nature, rivers, mountains, wild forests). In contrast, relative values are attributed to all useful and purposeful objects like cultural landscapes (Kant, 1785). For Beatrix Sitter-Liver (Koechlin, 2014, p. 140) a beau- tiful blooming flower expresses to the perceiving human an intrinsic value of the creature triggering respect for life. Many poets like Rainer Maria Rilke or John Berger found the place of their poetic language in nature and near-natural landscapes. Eventually, the objective characterof aesthetics is proven by neurobiological findings demonstrated by neuroscientist and psychotherapist Joachim Bauer (2011). He showed that an attractive and enriched environment leads to an activation of neural systems promoting intellectual, emotional and motoric activities of children but also elder persons.

Martin Seel (1991) gives another objective character of the beauty distinguishing three dimensions of the aesthetic effect of nature on humans: contemplation, correspondence and imagination. Contem- plative moments (e.g. a walk through a forest) describe an uninterested attention, which evokes in us unexpectedness, sensuality and a feeling of release of all prior constructs of meanings and purpose. A corresponding place is where we feel a coherent reflection of our proper understanding of life. Finally, imagination is conceived as the perception of nature as if it is an imagined artwork. These sensual ap- pearances are triggered mainly byfreenature and big natural sceneries, like the view out of the train of the Lake Geneva with the terraced vineyards of Lavaux (as mentioned by Seel).

Significance in Practice Attractive landscapes are a touristic and economic resource

Figure 8 The Sils lake as a touristic hotspot

The discovery of the Alps starting broadly in 17thcen- tury was driven by the scientific interest of gaining knowledge. The Alps became object of study and for- mation for young rich people of whole Europe. These travellers have transformed alpine mountains in their former negative and sometimes even horrible image (attributed by detached outsiders!) into an aesthetic fascinating nature on providing the basis for later alpine tourism as an important economic resource.

Literature

Bauer, J. (2011).Das Gedächtnis des Körpers: wie Beziehungen und Lebensstile unsere Gene steuern.

Piper, München.

Ginsborg, H. (2019). Kant’s Aesthetics and Teleology. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-aesthetics/ (accessed: May 2020).

Kant, I. (1785).Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten. J. F. Hartknoch Verlag, Riga.

Koechlin, F. (2014). Jenseits der Blattränder: eine Annäherung an Pflanzen. Lenos Verlag, Basel.

Seel, M. (1991). Eine Aesthetik der Natur. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a.M.

2.2 Value Judgement

This section discusses theories assigned to the overlapping part of theobject-relatedand theculture- relatedperception oflandscape. It is assumed, that landscape perception and evaluation are strongly connected with the perceived, and therefore, real landscape. Nevertheless, this value judgmentis compellingly influenced by the observer’s culture.

Figure 9 Value Judgement

2.2.1 Natural Beauty as Model for Arts

Main characteristics

Aristoteles, Leonardo da Vinci, Novalis

Antiquity, Renaissance, Romanticism

English garden architecture, Landscape planning, Land-art

Nature being judged as reference for objective beauty has a long “tradition". Already in antiquity, na- ture was as considered not only as the greatest artist but also as an interpreter for art works of any kind. The set phrasears imitatur naturamby Aristoteles has been known and is often used also in the Medieval and Renaissance period.Mimesis(the imitating) does not signify to copy the reality in a simple way, but to make use of the creative principles (the inner function,eidos) of the nature (Büttner, 2006, p- 67). In the Renaissance period of the 15th and 16th century, themagicalbeauty was also conceived as the invention and imitation of nature (Eco, 2004, p. 176). In his essay about landscape painting Leonardo recommended to study nature (with its prospective and its harmony) in

2.2. Value Judgement

the best possible way. As a conclusion of this ability to study nature’s principles, the artist became the real creator of the beauty substituting the former predominance of the nature. Novalis (and other representatives of the Romanticism) laid claim to the beautiful and holy profession to which the inter- preters of nature have been called (“Ein Verkündiger der Natur zu sein, ist ein schönes und heiliges Amt", (Freeman, 2006, p. 61)). For Novalis nature knows how to beautify everything, to animate every- thing, to persuade everything. With regard to the "Great Theories" of antiquity (the good, the true and the beautiful as the unity of all being) the rules of harmonious beauty as an ideal relation of propor- tion expressed by numbers (Pythagoras) are widespread in nature as well as in architecture and art works (see subsection 2.2.2). Ancient Greek mathematicians (e.g. Euclid) and later Fibonacci studied thegolden ratio, known since the 19th century as the golden cut, which was supposed to express the rule of the cosmic order of harmony (Liessmann, 2009, p. 19).

The beautiful landscape could be said to be an invention of the painting, because the painter is able to unify formal features of a landscape like mountains, woods, rivers, meadows, forming a wholeness which can be experienced (for a well-trained aesthetic eye) as a harmoniousensemble and hence as beautiful. In this context, English landscape gardening was strongly influenced by natural appear- ances like creating landscape paintings (e.g. Pückler-Muskau, 2014 ). Finally, land-art is since the late 1960s understood as an artistic inscription into a natural or rural environment. These art works are often moving and melting with winds and temperature, water and natural erosion or are ephemeral by fading away naturally. Other artists like Richard Long, Ian Hamilton Finlay or Swiss Martin Stützle inscribe their artistic expressions into natural materials like stones, grassland, seashores forming natural poetic sculptures

Significance in Practice Attractive green areas as a mimesis of nature

Figure 10 The Ermitage in Arlesheim

“All gardening is landscape painting", observed En- glish poet Alexander Pope in 1734. Planning and con- structing green areas like parks and gardens should follow natural principles which assure a wide accep- tance by visitors. The biggest English landscape gar- den in Switzerland, the Ermitage in Arlesheim BL from 1785, was inserted into a geomorphological interest- ing site. The architectural interventions all aimed to strengthen the pre-existing natural sceneries.

Literature

Büttner, S. (2006).Antike Ästhetik: Eine Einführung in die Prinzipien des Schönen. München.

Eco, U. (2004). Die Geschichte der Schönheit. Carl Hanser Verlag, München.

Freeman, V. G. (2006). The poetization of metaphors in the work of Novalis. Lang, New York.

Liessmann, K. P. (2009).Schönheit. Facultas, Wien.

Pückler-Muskau, H. (2014). Andeutungen über Landschaftsgärtnerei. Birkhäuser, Basel.

2.2.2 Rule Based Aesthetics

Main characteristics

Plato, Aristoteles, Vitruvius, Palladio, Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten, William Hogarth, William Gilpin

Antiquity, Renaissance, 18thcentury

Aesthetic formalism, architecture, landscape gardening

In general, an objective judgment is based on numbers and measurable values. Objectivity in land- scape assessment could also be based on mere formal features. Formalists consider lines, shapes, and colors as formal aesthetic aspects. While history, symbols, purposes, atmospheres or rational in- terpretations are not of their prime interest (Noaparast and Noaparast, 2011, p. 102ff). Therule-based aesthetics (Regelästhetik) has a long history, starting from the Greek Antiquity. As described in sub- section 2.2.1 the golden ratio is an expression of a divine harmony based on arithmetic and geometry.

Plato, who emphasized the importance of an intellectual perception of the idea of beauty (see subsec- tion 2.4.1), nevertheless “allowed" some practical objective criteria as the proportionality (symmetria, Ebenmass) to determine beauty (Büttner, 2006, p. 21). This involves the relative proportion of single parts to the whole and among each other. For Aristoteles the mathematical principles are not the only objective characters to recognize the idea of the beauty within a beautiful object. More decisive for the beauty are order (taxis), proportion (symmetria) and determination (Horismenon, das Einheitliche und Bestimmte eines Gegenstandes/Wesens) of an object. In Vitruvius’s essay about architecture (1st century B.C.) the criteria stability, utility and grace are listed as goals for good architecture. His aes- thetics of architecture has served for a long time as a guideline. Renaissance architects like Palladio implemented these ancient rules.

Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten marked in 1750 the philosophical concept of aesthetics by means of a definition of beauty as the imagined sensual perfection (vorgestellte sinnliche Vollkommenheit), that could be elaborated by virtue of a generally valid normative discipline of arts. Baumgarten developed aesthetics as a philosophy of sensual cognition, which he understood as an extension of rational scien- tific thinking. Sensual cognition does not mean a passive reception, but an active process that includes perception and thinking. This would involve universal rules, including besides order and proportion many other criteria (Majetschak, 2007, p. 27ff). However, already in the 18th century it became evi- dent, that the aesthetic experience of an artwork could not be explained by objective characteristics of single parts of it.

In 1753 English painter and printmaker, William Hogarth tried to solve the ancient mystery of the char- acteristics of beauty (Ullrich, 2005, p. 31ff) introducing new ideas. One of these is called the Line of Beauty and Grace, a wavy line, which he used in many of his engravings and paintings. The line symbol- ized movements like dancing (which should be elegant and graceful), the changes of directions and the variety in all dimensions. For Hogarth this line targeted a philosophy of a happy life with plenty of vari- ous moments in which the line connects every experience with many others. In practical approaches, English garden architects like Lancelot Brown or also Friedrich Ludwig von Sckell have used the line of

2.2. Value Judgement

beauty and grace in order to design serpentine ways for a variety of experiences throughout the land- scapes. Until today, this line is used for the revitalization of brooks and rivers and also in commercials for products.

Another rule for landscape beauty is the picturesque. English priest William Gilpin recorded in 1789 in his work on the picturesque in landscape painting, that great landscape sceneries like Claude Lor- rain’s paintings can be subdivided in theforeground,middlegroundanddistance(Bermingham, 1994, p. 77ff, Rodewald, 2011, p. 99ff). For Gilpin, the power of beauty lays in nature. He distinguished the pleasingly beautiful(described with smoothness,neatness, andelegance) which he considered as rather boring, from the picturesque beautiful. He ascribed the latter to natural forms uninfluenced by humans (characterized byroughness,ruggedness,varietyorcontrast) contrasting anthropogenic landscape forms (such as agricultural and flat lands).

Significance in Practice Linear structures in landscapes

Figure 11 Linear alleys in Val de Ruz

Geometric landscape features are often appreciated by the population because they are marking open wide landscapes and underlining roads and tradi- tional ways of communication between villages. Alleys constitute fascinating linear green ordering and con- necting structures, which emphasize the perspective and width of a landscape. The lines are often bended and mark the topography in an elegant way. Figure 11 demonstrates also Gilpin’s picturesque view onto a landscape.

Literature

Noaparast, K. B. and Noaparast, M. Z. B. (2011). Aesthetic Formalism, Reactions and Solutions. Wis- dom and Philosophy, 6(4), 101–112, https://ssrn.com/abstract=1986694.

Bermingham, A. (1994). System, Order, and Abstraction: The Politics of English Landscape Drawing around 1795. In: Mitchell, W. J. T., (ed.),Landscape and Power, 77 – 101. Chicago.

Büttner, S. (2006).Antike Ästhetik: Eine Einführung in die Prinzipien des Schönen. München.

Rodewald, R. (2011). Ihr schwebt über dem Abgrund: Die Walliser Terrassenlandschaften – Entste- hung, Entwicklung, Wahrnehmung. Rotten-Verlag, Visp.

Ullrich, W. (2005). Was war Kunst? Biographien eines Begriffs. Fischer, Frankfurt a.M.