Assessing Speaking for the E8 Standards:

The E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment

Technical Report 2017

Andrea Kulmhofer

Fiona Lackenbauer

Rebecca Sickinger

Claudia Steininger

Bundesinstitut für Bildungsforschung, Innovation & Entwicklung des österreichischen Schulwesens

Alpenstraße 121, 5020 Salzburg

www.bifie.at

Assessing Speaking for the E8 Standards: The E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment Technical Report 2017

BIFIE Salzburg (Hrsg.), Salzburg, 2017.

The Technical Report 2017 has been adapted from the Technical Report 2012:

Claudia Mewald Otmar Gassner Rainer Brock Fiona Lackenbauer Klaus Siller

Der Text sowie die Aufgabenbeispiele können für Zwecke des Unterrichts in österreichischen Schulen sowie von den Pädago gischen Hochschulen und Universitäten im Bereich der Lehrer aus-, Lehrerfort- und Lehrerweiterbildung in dem für die jeweilige Lehrveranstaltung erforderlichen Umfang von der Homepage (www.bifie.at) heruntergeladen, kopiert und verbreitet werden. Ebenso ist die Vervielfältigung der Texte und Aufgabenbeispiele auf einem anderen Träger als Papier (z. B. im Rahmen von Power-Point-Präsentationen) für Zwecke des Unterrichts gestattet.

Autorinnen und Autoren:

Andrea Kulmhofer Fiona Lackenbauer Rebecca Sickinger Claudia Steininger

Contents

3 1 INTRODUCTION 3 1.1 Using the Technical Report

3 2 SPEAKING TO COMMUNICATE

5 3 THEORETICAL MODELS

5 3.1 Models of communicative competence 6 3.2 Communicative competence in the CEFR 6 3.2.1 Linguistic competence

6 3.2.2 Sociolinguistic competence 7 3.2.3 Pragmatic competence

7 3.3 The nature of language in unplanned speech

7 4 E8 SPEAKING ASSESSMENT DEVELOPMENT 9 4.1 Test taker characteristics

9 4.2 Settings and demands of the assessment (context validity) 9 4.2.1 Topic familiarity

9 4.2.2 Prompt writing 9 4.2.3 Rubrics 12 4.2.4 Task types 13 4.2.5 Prompt sets 13 4.2.6 Time constraints

14 4.3 Authenticity of tasks (cognitive validity) 14 4.4 Assessment (scoring validity)

14 4.4.1 Assessment criteria

14 4.4.2 Assessment Scale & Scale Interpretations 19 4.4.3 Rating

20 4.4.4 Assessor/Interlocutor training

21 5 FEEDBACK

21 6 ASSESSING E8 SPEAKING – A SUMMARY 21 6.1 Purpose of the assessment

21 6.2 Description of assessment participants 21 6.3 Task level

22 6.4 Test Construct

22 6.5 Structure of the assessment 22 6.6 Time allocation

22 6.7 Rubrics

22 6.8 E8 Speaking Assessment Scale 23 6.9 Prompt Sets

23 7 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 23 8 BIBLIOGRAPHY

25 9 APPENDICES

Abbreviations

ANCFL Austrian National Curriculum for Foreign Languages (Österreichischer Lehrplan)

BIFIE Bundesinstitut für Bildungsforschung Innovation und Entwicklung des österreichischen Schulwesens

CANCODE Cambridge and Nottingham Corpus of Discourse in English CEFR Common European Framework of Reference for Languages:

Learning, Teaching, Assessment E8 Englisch 8. Schulstufe

E8 BIST Bildungsstandards Lebende Fremdsprache (Englisch), 8. Schulstufe KOW knowledge of the world

Key Terms:

Assessor the person who assesses the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment performance(s) of the student(s). This could be the subject teacher, language assistant, second teacher, or other relevant and qualified person in the classroom.

Interlocutor the person who guides the student(s) through the relevant prompt set. This could be the subject teacher, language assistant, second teacher, or other relevant and qualified person in the classroom.

Global error a systematic error. For the purposes of the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment, we consider this to be an error that interferes with understanding.

L1 first language (for the purposes of this technical report, L1 is assumed to be German)

Local error a mistake (not a systematic error). For the purposes of the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment, we consider this to be an accidental mistake or an error that is so minor as to not interfere with understanding.

3 Speaking to communicate

1 Introduction

This Technical Report updates the Technical Report 2012. It has been written to support English teachers, particularly those teaching in the 8th school year in AHS and NMS schools in Austria. It describes the new E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment.

The assessment of E8 Speaking has now been placed at the centre of the classroom, and, therefore prominently in the teaching and learning curriculum. An added bonus of moving the assessment of E8 Speaking to the classroom is that results will be immediately avail able to the people (teachers and learners) who can best use the information generated from the assessment(s). Thus, they will be able to make timely interventions for further improvements in the teaching and learning of English.

1.1 Using the Technical Report

The Technical Report provides a brief theoretical background to the assessment of speaking and communicative competence. It explains the new E8 Speaking Assessment including the setting, the assessment scale, training for inter locutors/assessors, and the use of resultant data. It is highly recommended that all AHS/NMS English teachers make use of the online training platform and use the E8 Speaking materials to assess speaking in the 8th school year with the aim of further improving the teaching and learning of speaking in their classroom.

2 Speaking to communicate

‘Speaking is one of the most complex and demanding of all human mental operations’ (Taylor, 2011: 70) and yet for language learners, it ‘is widely accepted that speaking is… the most under-developed skill’ (TES, 2017).

Spoken language is significantly different from written text as the CANCODE speaking corpus (Cambridge and Nottingham Corpus of Discourse in English) demonstrates. The difference between spoken and written language is found not only in lexis but also in grammar, and this should be acknowledged in teaching as well as in testing and assessment (McCarthy, 2006).

As well as recognising this distinction between spoken and written texts, there is a need to appreciate the im- portance of encouraging pupils to expand their range within the language. This can be achieved by prioritising range over accuracy in the teaching and assessment of both speaking and writing.

Getting the message across is far the most important to reward. This implies that other marks are likely to favour clarity (e.g. accurate pronunciation and intonation), flow of language, range of language appropriate to the task and, least important, accuracy. Minor errors (those which do not have an impact on meaning) can be virtually ignored. Even more significant errors, such as verb tense errors, may not deflect the listener too much from the intended meaning. At all stages in the language learning process, students need to know that actually communi- cating takes priority over being accurate. The same principles apply to writing. Assessment mark schemes and task rubrics should reflect this.

(Smith and Conti, 2016: 207).

This approach has been recognised in the Austrian National Curriculum for Foreign Languages (ANCFL):

Ziel des Fremdsprachunterrichts ist die Entwicklung der kommunikativen Kompetenz in den Fertigkeitsbereichen Hören, Lesen, An Gesprächen teilnehmen, Zusammenhängend Sprechen und Schreiben…

…Als übergeordnetes Lernziel in allen Fertigkeitsbereichen ist stets die Fähigkeit zur erfolgreichen Kommunikati- on – die nicht mit fehlerfreier Kommunikation zu verwechseln ist – anzustreben.

(AHS = BMB, 2000: 1 & 2) (NMS = RIS, 2012: 36 & 38)

4 Speaking to communicate

This range over accuracy approach is implicit in the E8 Speaking Assessment Scale (appendix i) and is an important part of the training (for more detail see: https://moodle.bifie.at).

The Common European Framework for language learning, teaching and assessment (CEFR) divides language into 5 skills: listening and reading (understanding), writing, and speaking, which is divided into spoken pro- duction and spoken interaction. In the E8 Standards (RIS, 2009: 12-13), 5 skills are also acknowledged. The E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment covers both spoken production and spoken interaction when monologue and dialogues are assessed.

The E8 Standards encourage teachers and students to address the five skills equally and this requirement is explicitly stated in the AHS and NMS curriculums for English:

Die Fertigkeitsbereiche Hören, Lesen, An Gesprächen teilnehmen, Zusammenhängend Sprechen und Schreiben sind in annähernd gleichem Ausmaß regelmäßig und möglichst integrativ zu erarbeiten und zu üben.

(AHS = BMB, 2000: 2) (NMS = RIS, 2012: 38)

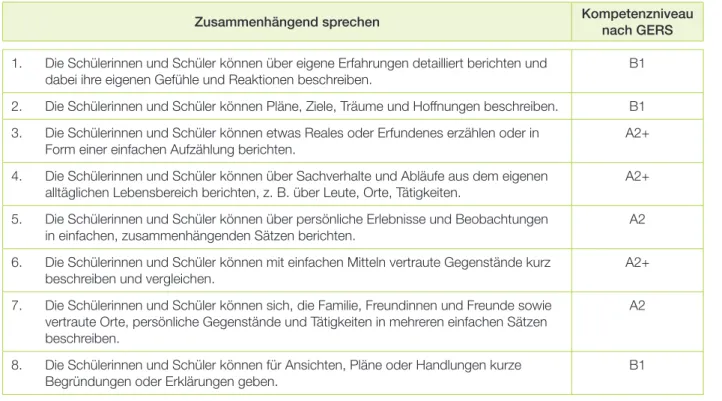

To assist teachers in the classroom, the E8 Standards describe what language learners should be able to do in spoken production and spoken interaction:

Zusammenhängend sprechen Kompetenzniveau

nach GERS 1. Die Schülerinnen und Schüler können über eigene Erfahrungen detailliert berichten und

dabei ihre eigenen Gefühle und Reaktionen beschreiben.

B1

2. Die Schülerinnen und Schüler können Pläne, Ziele, Träume und Hoffnungen beschreiben. B1 3. Die Schülerinnen und Schüler können etwas Reales oder Erfundenes erzählen oder in

Form einer einfachen Aufzählung berichten. A2+

4. Die Schülerinnen und Schüler können über Sachverhalte und Abläufe aus dem eigenen alltäglichen Lebensbereich berichten, z. B. über Leute, Orte, Tätigkeiten.

A2+

5. Die Schülerinnen und Schüler können über persönliche Erlebnisse und Beobachtungen in einfachen, zusammenhängenden Sätzen berichten.

A2

6. Die Schülerinnen und Schüler können mit einfachen Mitteln vertraute Gegenstände kurz beschreiben und vergleichen.

A2+

7. Die Schülerinnen und Schüler können sich, die Familie, Freundinnen und Freunde sowie vertraute Orte, persönliche Gegenstände und Tätigkeiten in mehreren ein fachen Sätzen beschreiben.

A2

8. Die Schülerinnen und Schüler können für Ansichten, Pläne oder Handlungen kurze Begründungen oder Erklärungen geben.

B1

Table 1: The BIST descriptors for spoken production

5 Theoretical Models

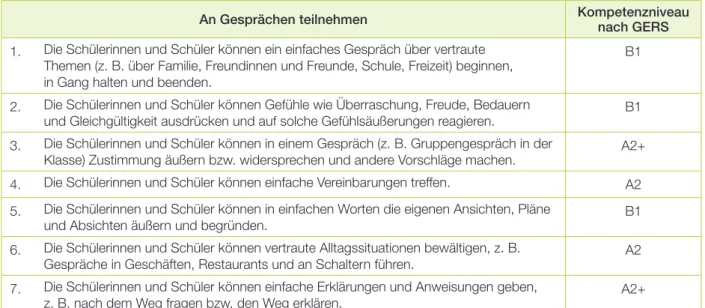

An Gesprächen teilnehmen Kompetenzniveau

nach GERS 1. Die Schülerinnen und Schüler können ein einfaches Gespräch über vertraute

Themen (z. B. über Familie, Freundinnen und Freunde, Schule, Freizeit) beginnen, in Gang halten und beenden.

B1

2. Die Schülerinnen und Schüler können Gefühle wie Überraschung, Freude, Bedauern

und Gleichgültigkeit ausdrücken und auf solche Gefühlsäußerungen reagieren. B1 3. Die Schülerinnen und Schüler können in einem Gespräch (z. B. Gruppengespräch in der

Klasse) Zustimmung äußern bzw. widersprechen und andere Vorschläge machen. A2+

4. Die Schülerinnen und Schüler können einfache Vereinbarungen treffen. A2 5. Die Schülerinnen und Schüler können in einfachen Worten die eigenen Ansichten, Pläne

und Absichten äußern und begründen. B1

6. Die Schülerinnen und Schüler können vertraute Alltagssituationen bewältigen, z. B.

Gespräche in Geschäften, Restaurants und an Schaltern führen. A2

7. Die Schülerinnen und Schüler können einfache Erklärungen und Anweisungen geben,

z. B. nach dem Weg fragen bzw. den Weg erklären. A2+

Table 2: The BIST descriptors for spoken interaction

Some current textbooks approved by the Austrian government (e.g. More! series) have included additional targeted speaking activities since the inception of the E8 Speaking Test in 2013. This increase in activities for speaking supports the teacher in teaching all the skills equally in the classroom.

3 Theoretical Models

Modern testing of speaking draws on a history of competence models that have impacted upon the design of testing and assessment procedures (Fulcher and Davidson, 2007). However, it is important to always remember that ‘conditions in the classroom are very different to those in real-life’ (Grauberg, 1997: 201) and the teaching and particularly the assessment of speaking are artificial constructs.

3.1 Models of communicative competence

Canale and Swain (1980: 3) state that ‘Chomsky’s (1965)… claim is that competence refers to the linguistic system (or grammar) that an ideal native speaker of a given language has internalised’; and according to Luoma (2004: 97) ‘[c]ommunicative competence emphasises the users and their use of language for communication.’

In his paper ‘On communicative competence’, Hymes (1972: 282) states that ‘[c]ompetence is dependent upon both (tacit) knowledge and (ability for) use’. Bagarić and Djigunović (2007: 95) point out that Widdowson (1983) built on these ideas and ‘made a distinction between competence and capacity... [where] he defines competence i.e. communicative competence, in terms of the knowledge of linguistic and sociolinguistic con- ventions. Under capacity… he understood the ability to use knowledge as means (sic) of creating meaning in a language’. This distinction between competence and capacity is a key aspect of successful and meaningful com- munication, and so a predominant feature in the assessment of spoken performances in E8 Speaking.

Bachman (1990: 84) pursues a similar concept and describes communicative language ability (CLA) ‘as con- sisting of both knowledge, or competence, and the capacity for implementing, or executing that competence in appropriate, contextualized communicative language use’.

Canale and Swain (1980: 29-30) divide communicative competence into further components: grammatical competence, sociolinguistic competence (sociocultural rules of use and rules of discourse), and strategic com- petence (including verbal and non-verbal communication strategies).

6 Theoretical Models

3.2 Communicative competence in the CEFR

Many European countries use the CEFR as a frame for their own national curriculums and assessment models (Broek and van den Ende, 2013). Similarly the E8 Speaking Standards (Mewald et al., 2012) and the new E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment are based upon the language competences described in the CEFR.

According to the CEFR (Council of Europe, 2001: 108), users/learners employ their ‘general capacities...

together with more specifically language-related communicative competence’ in order to fulfil communicative purposes. Thus, the CEFR divides communicative competence into three components (Council of Europe, 2001: 108):

Communicative competence… has the following components:

linguistic competences;

sociolinguistic competences;

pragmatic competences.

3.2.1 Linguistic competence

In the description of linguistic competence, the CEFR refers to ‘the main components of linguistic competence defined as knowledge of, and ability to use, the formal resources from which well-formed, meaningful messages may be assembled and formulated’ (Council of Europe, 2001: 109). Linguistic competence includes:

lexical competence,

grammatical competence,

semantic competence,

phonological competence,

orthographic competence,

orthoepic competence.

The E8 Speaking Assessment Scale is founded on 4 of these competences:

semantic competence, reflected in the dimension Task Achievement & Communication Skills e.g. the orga- nisation of meaning and the structuring of ideas

phonological competence, assessed in Naturalness of Speech including intonation, sentence stress, rhythm, and general pronunciation

grammatical competence, targeted in Grammar e.g. tenses, phrases, clauses, sentences etc. (‘the organisation of words into sentences’ (Council of Europe, 2001: 113) )

lexical competence, the main focus in Vocabulary including stock phrases, collocations, chunks of language, and idioms etc.

Orthographic competence (knowledge of the symbols used in a written text) and orthoepic competence (ability to decode words and thus read a text) are not included in the E8 Speaking Assessment Scale.

3.2.2 Sociolinguistic competence

Sociolinguistic competence is described as the ‘knowledge and skills required to deal with the social dimension of language use’ (Council of Europe, 2001: 118). This includes, for example: greetings, forms of address, turn- taking conventions, politeness, expressions of feelings (e.g. surprise, happiness, sadness, interest and indifference etc.).

In the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment, ‘introductions and conventions for turntaking’ and politeness con- ventions are both likely to be used (Council of Europe, 2001: 119) dependent on the task and the descriptor being assessed. These should be assessed in the dimension Task Achievement & Communiction skills (‚turn- taking skills‘ and ‚initiating discourse‘).

7 E8 Speaking assessment development

3.2.3 Pragmatic competence

According to the CEFR, ‘[p]ragmatic competence deals with the ability to organise, structure and arrange messages (discourse competence), to perform communicative functions (functional competence), and to sequence turns according to interactional or transactional schemata (design competence)’ (Council of Europe, 2001: 123).

Pragmatic competence deals with:

discourse competence – ‘the ability to organise, structure, and arrange messages’ (Council of Europe, 2001:

123). In the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment this competence can best be demonstrated in the mono- logue part (appendix iv), where the students are most likely to produce text that features whole sentences. In the short and long dialogues (appendix v), the nature of interactive talk will primarily trigger the use of short idea units and incomplete sentences, strings of short phrases, as well as short turns.

functional competence – the ability to interact with conversational partners. In the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment this competence is demonstrated in the dialogue parts (appendix v).

design competence – the ability to sequence turns which would include questions, requests, offers, apologies, acknowledgements, and responses. In the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment this competence is also demonstrated in the dialogue parts (appendix v).

Pragmatic competence would be assessed in the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment in the dimension Task Achievement & Communication Skills (‘interactive behaviour’, ‘turn-taking skills’, ‘initiating, maintaining or closing discourse’ etc.).

3.3 The nature of language in unplanned speech

According to Thornbury (2009: 2–4), ‘speech production takes place in real time and is therefore essentially linear. Words follow words, and phrases follow phrases.’ And to ‘compensate for limited planning time [there is often a] chaining together of short phrases and clause-like chunks, which accumulate to form an extended turn’.

Luoma (2004:13) depicts unplanned speech as ‘spoken on the spur of the moment, often in reaction to other speakers’ and typified by ‘incomplete sentences’.

This depiction of speech as unplanned, incomplete, and consisting of chunks reflects the output expected from students during the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment.

4 E8 Speaking assessment development

The design and development of the original E8 Speaking Test is described in the Technical Report 2012 (Mewald et al.: 13–55). What follows is a brief description of the changes made to improve and adapt the original design to suit the new concept of E8 Speaking as a skill taught and assessed in the classroom, with an explanation of key features of the assessment design including the E8 Speaking Assessment Scale.

Although the assessment of E8 Speaking is now classroom-based, we have still followed the framework for con- ceptualising Speaking test validity as shown on the next page (Taylor, 2011: 28) where possible.

8 E8 Speaking assessment development

Figure 1: A framework for conceptualising speaking test validity (adapted from Taylor, 2011: 28)

9 E8 Speaking assessment development

4.1 Test taker characteristics

Although the model on the previous page refers to test takers, we will refer to pupils or students as there is no longer an E8 Speaking Test but instead a teacher-led assessment.

O’Sullivan and Green (2011: 61) state ‘[a]voiding test bias favouring or penalising any group of test takers must be a priority for the test provider.’ The E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment has been designed for students in the 8th school year who are predominantly between the ages of 13 and 14 and, although a certain homogeneity can be expected in this cohort, the E8 Speaking Team tried to ensure that the materials offered to classroom teachers avoided bias. During item writing, this was an important consideration and this consideration continued into the piloting (and pre-piloting) stage(s) of test items where schools selected were chosen for their range of geo- graphical and social intakes (George et al., 2015).

The setting for the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment will almost always be the regular classroom with the assessment being carried out by the English teacher. Therefore, aspects such as short/long term illnesses, emo- tional states, motivation etc. should be known to the teacher and accommodations/modifications/special arrangements can be made as necessary.

In formal speaking examinations (such as the 2013 E8 Speaking Test), interlocutor interactions are usually highly scripted and controlled (through scripts and training). Through scripted materials supported by online training and video exemplars (https://moodle.bifie.at/), attempts have been made by the E8 Speaking Team to support a standardised assessment for all pupils. However, we recognise that an assessment conducted by the subject teacher in the classroom environment obviously lacks the rigour of an external test. For this reason, data resulting from the assessment is only for the use of the relevant teacher so that they can improve the teaching and learning of speaking in their classroom rather than for a wider audience and broader purposes.

4.2 Settings and demands of the assessment (context validity)

The setting and demands (task) of the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment will clearly differ from its predecessor the E8 Speaking Test. An externally assessed formal model has been replaced by a teacher-led, classroom-based format.

4.2.1 Topic familiarity

The vast majority of students taking the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment will have been following the curriculum for English (AHS = BMB, 2000; NMS = RIS, 2012) and using the approved textbooks for teaching English in Austria (approved by the Bundesministerium für Bildung). They should therefore be familiar with the 17 topic areas that form part of the Construct Space (appendix ii). Test items (prompts) have been generated from these topic areas.

4.2.2 Prompt writing

After the 2013 E8 Speaking Test, prompt evaluation was carried out on all the speaking prompts in the Prompt Bank in preparation for the next round of testing. A set of quality assurance criteria (appendix iii) was drawn up to enable the E8 Speaking Team to select or discard prompts.

Current prompt sets (examples are shown in appendices iv, v, vi) have all been adapted by members of the E8 Speaking Team in accordance with the quality assurance criteria (appendix iii) and have been piloted. The E8 Speaking Team will follow the same procedure for new prompts.

4.2.3 Rubrics

The input language has been designed to be as simple and short as possible. ‘In general, the longer the input candidates have to process, the higher the cognitive demand on them, and the more difficult the task’ (Galaczi

10 E8 Speaking assessment development

and ffrench, 2011: 145) and therefore, the input language is no higher than CEFR A2 level and kept to a minimum throughout the prompt materials. Piloting was carried out to ensure that the rubrics are clear and that test materials can be successfully completed by students in possession of the lexical and grammatical resources expected of pupils in the 8th school year in Austria (as defined by the curriculum). For example:

Monologue

Draft 02.08.2017

17

11 E8 Speaking assessment development

Dialogues

Draft 02.08.2017

18

12 E8 Speaking assessment development

4.2.4 Task types

As Galaczi and ffrench note, ‘[i]n speaking assessment, response format types typically refer to patterns of inter- action, and can roughly be divided into monologic and dialogic’ (Galaczi & ffrench, 2011: 113).

The E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment, like its predecessor the E8 Speaking Test, offers both types of inter- action1.

Generally, tasks have been designed to encourage students to add their own ideas and to use their own language, and to balance language output from each pupil.

1 However, in the new assessment, as the teachers should be well known to their pupils, the interview part of the test is no longer needed.

Draft 02.08.2017

19 4.2.4 Task types

As Galaczi and ffrench note, ‘[i]n speaking assessment,

response format types typically refer to patterns of interaction,

and can roughly be divided into monologic and dialogic’ (Taylor,

2011: 113).

13 E8 Speaking assessment development

Different tasks demand the use of different text types. These are listed in the Construct Space (see appendix ii) and are unchanged from previous years.

Monologue

One topic is offered to each student.

Each monologue has 6 content points providing a guideline for the student. The content points are spread over the page rather than listed in an attempt to encourage pupils to speak more widely about the topic rather than working their way down a prescribed list.

As before, standardised repair questions are provided and these are listed next to the relevant content points in the prompt sets for ease of use. These can be used by the interlocutors to support the pupils in cases of communication breakdown.

Short dialogue

Short dialogues were originally added to the E8 Speaking materials to ensure that transactional communicative strategies could be shown by test takers. And in many of the tasks, an agreement needs to be reached. These remain in the new format.

To minimise cognitive load, pictures have been used wherever possible rather than text. This has the added benefit of giving the students less language to lift from the prompt.

One general repair question is provided.

Long dialogue

Piloting highlighted the need for further refinement of the design of the long dialogue to encourage a discussion between students rather than a question and answer session. Changes have been made including an increase in the use of pictorial inputs over text.

Question words have been moved to the bottom of the page and form a question word word-bank encour aging students to generate their own questions rather than simply using given input phrases.

Repair slips are provided to re-start the discussion if a pair is no longer able to maintain the dialogue.

4.2.5 Prompt sets

In the new E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment, teachers are offered three possibilities:

a full prompt set (including monologue, and short and long dialogues) (appendix vi)

a monologue prompt set (appendix iv)

a dialogue prompt set (including short and long dialogues) (appendix v).

The assessment of both spoken production and spoken interaction can only be achieved through the use of a full prompt set (monologue and dialogues), however the E8 Speaking Team has recognised that time in the classroom setting is a limiting factor, and therefore, other options have been designed. Teachers might only have time to assess monologues or dialogues. Or, teachers might wish to assess monologues at one point in the academic year, and dialogues at another.

4.2.6 Time constraints

Speaking, as previously mentioned, is normally an unplanned, unscripted performance. The time constraints explicit in the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment, both the parameters given for planning time and speaking time and the added constraint of the classroom setting within a timetabled school day, must clearly have an impact on students’ performances. Due to the assessment format, this cannot be standardized across settings.

Although guidelines (see page 22) are given, the individual teacher must manage their own assessment process.

14 E8 Speaking assessment development

4.3 Authenticity of tasks (cognitive validity)

Cognitive validity has been described as ‘the extent to which the tasks in question succeed in eliciting from candidates a set of processes which resemble those employed in a real-world speaking event’ (Field, 2011: 65).

A key word in this sentence is ‘resemble’: as Fulcher and Davidson (2007: 63) point out ‘authentic’ tasks in a test taking or assessment environment can only allow ‘us to observe the use of processes that would be used in real-world language use’. And this is the aim in the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment where tasks are as authentic as possible.

During the re-design of the E8 Speaking tasks – prompted by the change in assessment policy from formal, external testing to teacher assessment, and after the piloting of the tasks – the E8 Speaking Team further adapted the prompt sets. These changes were made to include further simplified interlocutor rubrics and more ‘visual support for conceptualisation [for students thus avoiding] weighting assessment… too heavily in favour of the test takers’ imagination rather than their language’ (Field, 2011: 89).

4.4 Assessment (scoring validity)

The E8 Speaking Assessment Scale (appendix i) has been amended since its inception, partly to align it more closely with the E8 Writing Rating Scale and partly to simplify the scale further in preparation for its use by subject teachers for assessment rather than as a formal, external testing tool.

4.4.1 Assessment criteria

The four assessment criteria (Task Achievement & Communication Skills, Naturalness of Speech, Grammar, and Vocabulary) are given equal weighting and are seen as equally important in E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment.

However, an aspect of a candidate’s spoken language could be assessed in more than one dimension e.g. a good phrase could help the turn-taking during the dialogues and therefore be assessed for Task Achievement, but the lexis used would also be considered in the Vocabulary dimension.

4.4.2 Assessment Scale and Scale Interpretations

Obviously, an assessment scale has to be capable of assessing the responses elicited by the set task. Therefore, the criteria within the scale should be defined in a way that any given response would receive the same assess- ment regardless of who the assessor is or when the response is assessed. As the subject teacher will now be the assessor, and probably the interlocutor as well, working in real-time, an E8 Speaking Rating Sheet (appendix vii) has been developed to assist the teacher in this potentially demanding task. The E8 Speaking Assessment Scale has been duplicated and combined with columns for easy ‘ticking off’ whilst pupils are talking. While we acknowledge that reliability across schools, classes, and teachers, is almost impossible to ensure, it is hoped that by providing training and an online platform offering benchmarked performances and advice, teachers will be supported in the role as assessor (and interlocutor).

As mentioned above, the E8 Speaking Assessment Scale is divided into 4 dimensions – the four assessment criteria: Task Achievement & Communicative Skills, Naturalness of Speech, Grammar and Vocabulary. These dimensions have been adapted since the first iteration – clarity is now included in Task Achievement & Com- municative Skills which fits more naturally with the Council of Europe definitions of competences (2001: 9–14).

Each part of the assessment is assessed holistically and the students’ scores can be input into the Data Assessment Tool to provide teachers and pupils with feedback.

Each dimension is divided into 7 bands. Descriptors are given for bands 1, 3, 5, and 7. Bands 0, 2, 4, and 6 cover those performances that are either slightly above or slightly below an adjacent band.

To provide teachers with further information to assist with assessments, scale interpretations discussing each dimension follow.

15 E8 Speaking assessment development

Scale Interpretation: Task Achievement & Communication Skills

In Task Achievement and Communication Skills the following are assessed:

the information the test takers provide (propositional precision),

the quality of the narrative (thematic development, primarily in the monologue part),

the ability to interact with a partner (turn-taking in the dialogues).

Propositional precision refers to the information that is communicated in the performance as well as to the successful completion of a communicative speech act. In propositional precision we ask ourselves: what is the information we get like? Is it detailed, concrete, limited, or more or less non-existent?

In the monologue part, students are asked to give information about a given topic. In addition they are provided with content points. Thematic development primarily refers to the monologue part. It deals with the way the speaker develops a speech act with respect to the given theme. If individual ideas (main points) are expanded with relevant detail, thematic development has been successful.

The content points are to be seen as guiding points for students to help them to speak freely for two minutes about their topic, but they are not mandatory and pupils are not penalised if they do not address them. The assessor must concentrate on the overall information that the student is able to pass on and its quality, and evaluate it according to the assessment scale. We expect students to talk about the given topic and to give infor- mation that is relevant to that topic.

If the student is unable to continue speaking, the repair questions can be used to help them formulate ideas and produce language relevant to the topic. As students are supposed to produce a flow of discourse in the mono- logue section, and not interact with the interlocutor, it will not be possible to assess the true level of candidates’

communication skills here. If, however, they do interact by asking for the translation of a German word in English (e.g. What is ‘Schläger’ in English?) they should receive the support necessary to carry on.

In turn-taking, we assess the students’ ability to interact with each other. This can be seen as the ability to begin, maintain, and end a conversation. Students may use:

chunks of language (e.g. What I want to say is…, First of all I want to say that…, If you want to do me a favour … etc.)

stock phrases (e.g. I agree with you, I think so too, I see what you mean, but I think…, I don’t think so, What do you think?, And you? etc.)

discourse markers (e.g. well, I’d just like to say, right, now, anyway, I mean, oh, good, great, okay, then etc.)

formulaic language (e.g. pause fillers: like, er, uhm, hmm, yeah; asking for repetition: Could you say that again, please?, Sorry? What was that?; paraphrase: It’s a kind of…, You mean… etc.).

In the short dialogue the students are asked to participate in a functional discourse. The functional aspect of the short dialogue often requires the students to come to a defined result. We can expect the students to exhibit turn-taking skills in order to achieve the task that may be an invitation, an excuse, a purchase, a decision-making process etc. We can thus expect the students to show, in a guided way, the extent to which they are able to initi- ate, maintain, and close a conversation; and how effective they are when doing this. Good speakers will have no problems f ormulating the necessary questions to accomplish the task. Utterances containing suggestions (e.g.

Would you ...?), agreement (e.g. Me too.), or disagreement (e.g. No, I don’t.), and their quality will also indicate communicative competence. Other indicators of communicative competence will be the use of stock phrases such as of course, and not at all and the frequency of their use.

The long dialogue is guided by key words or phrases, images, and a question word word-bank that together serve the same function as the content points in the monologue. They are stimuli and not compulsory items to be dealt with. Students might develop a successful conversation about the topic solely following their own ideas. As students should interact with each other, and may in some cases even interrupt each other, it is less likely that they will have the opportunity to provide too much detailed information before they are confronted

16 E8 Speaking assessment development

with another point by their partner. Students should be able to initiate, maintain, and end parts of the conver- sation. However, when there is a marked imbalance or breakdown of communication, the interlocutor should intervene.

Speakers with good communication skills will try to provide a good balance in their discussion using learnt phrases such as I think… In my opinion… etc. We can expect good speakers to use phrases such as Me too, I agree/disagree, Really?, Cool etc. when reacting to their partner’s utterances. And finally, stock phrases such as And what about you? What do you think? What’s your opinion? will be employed by good speakers to encourage verbal output from their conversation partners.

In the assessment of Task Achievement & Communication Skills the test takers are allocated one of seven bands.

Band 7 performers give rich, clear and concrete information and are able to expand main points with rele- vant examples. They are effective in turn-taking.

Band 5 performers give clear and concrete information and they develop a straightforward narrative in the monologue part. They are capable of turn-taking and can initiate, maintain, and close a conversation.

Band 3 performers give limited information and in the monologue they give a simple list of points at sentence or word-group level. They can ask basic questions in the dialogues. The students may partly rely on the interlocutor’s support through repair questions to keep going.

Band 1 performers give very little information and cannot go beyond simple statements or negations on word or word-group level in the monologue. This will mostly result from the fact that they cannot develop a narrative independently and rely on the interlocutor’s repair questions. They may make attempts to ask questions (e.g. raising intonation) but are not effective in questioning. The interlocutor may have to use the repair questions to keep the dialogue going.

Scale Interpretation: Naturalness of Speech

A performance is considered natural if the pronunciation is intelligible and the intonation supports meaning.

In order to achieve this, performances have to reach a certain level of fluency and phonological flow. As Luoma (2004: 88) points out ‘[f]luency is a thorny issue in assessing speaking’ as many different meanings have been assigned to the term (including the basic distinction between the general meaning of being fluent in languages and definitions used by linguistics).

Definitions of fluency often include references to flow or smoothness, rate of speech, absence of excessive pausing, absence of disturbing hesitation markers, length of utterances, and connectedness.

(Koponen in Luoma, 2004: 88).

Participants of fluent conversations retrieve chunks of language and provide interactive support to the flow of talk, helping each other to be fluent and creating confluence in the conversation using natural pauses.

In the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment, naturalness of speech surfaces as phonological flow in the sense that natural pronunciation and intonation should make it possible for native speakers of English to understand the speaker’s messages.

In the monologue, the speaker is expected to speak fluently and naturally for two minutes and their narrative should flow in the sense that it is as coherent and cohesive as unplanned speech can be. That is, we cannot expect elaborate, complex sentences of the quality of a written text, but we expect the students to use simple connectors (and, but, because, first, then, later, at last, personal pronouns etc.) and possibly some stock phrases that highlight the beginning, the main part, or the end of their monologue (I will talk about..., the most important thing..., what I like best is..., all in all this was..., finally I would like to say that...). In the dialogues discourse markers (well…, you know…, right...), formulaic speech (have a nice day…, see you…, and you...) as well as pre-fabri- cated chunks and phrases (would you like a...?, the thing is..., are you with me?) make spoken language fluent and compensate for the cognitive demands of grammatical or lexical planning in spoken text(s).

17 E8 Speaking assessment development

As in all dimensions, in the assessment of Naturalness of Speech the students are allocated one of seven bands.

Band 7 performances are fluent and spontaneous. The performances are delivered at a fairly even tempo and pauses are naturally placed. The speakers will produce longer stretches of language (especially in the mono- logue part) with pronunciation and intonation that make the performance easily intelligible. It is possible that minor inaccuracies could occur.

Band 5 speakers show some degree of fluency, although some pausing for lexical or grammatical planning or repair may be necessary. The speakers produce connected stretches of language that are long enough for pronunciation and intonation to sound intelligible. At this level some mispronunciations that do not impair communication can be tolerated.

Band 3 performances are interrupted by noticeable pauses, hesitations, and false starts, which sometimes cause the breakdown of communication. The contributions and exchanges are short and generally intelligibly pronounced; too short, however, to develop natural intonation. Extensive pauses, overly short contributions, and/or poor pronunciation may cause communication to break down.

Band 1 performances frequently suffer from a breakdown of communication this may be caused by hesita- tions, the use of very short and isolated utterances, and/or frequent mispronunciations making it hard for native speakers to understand the message.

Scale Interpretation: Grammar

The scale for grammar comprises descriptors for range and control. Therefore, the assessor evaluates the student’s ability to make use of a range of grammatical structures, and the level of their accuracy. The focus is on gram- matical forms that by creating meaning, and being reasonably correct, accomplish successful communication. It is important for assessors to remember that spoken grammar is different to written grammar.

Although there is some planning time, speech production in the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment takes place in real time and is therefore considered to show the characteristics typical of unplanned speech. Thus, the per- formances are expected to be linear and the students will mostly use an add-on strategy of stringing short idea units together. While we generally expect complete sentences in the monologue, the dialogues will primarily feature incomplete sentences, word groups, short phrases, or chunks of language. We have to acknowledge that incomplete utterances (Could be), ellipsis (Sounds like a good idea), syntactic blends (I’ve been to London…

last year), or vague language (kind of machine) are natural. Moreover, present simple, past simple, active verb forms, modal verbs, personal pronouns, and determiners will be frequent; and in contrast, continuous forms, perfect forms, and the passive will be rare. More able students will show their speaking ability by using more complex forms than might be expected, for example: verbs can be modified; adverbs can be used; different sentence structures can be utilised such as statement, question, negation, command/directive, or exclamation.

In the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment, range overrules accuracy in the sense that rich grammatical range through risk taking is encouraged, while inaccuracies that do not impair meaning play a minor role. The more varied the grammatical range, the higher the band. Risk taking which results in rich structures, but reduced control, does not necessarily lead to the performance being placed at a lower band.

Local errors that do not hinder communication are not considered to be problematic unless their frequency impairs the message. Only global errors that interfere with the comprehensibility of the text will result in the awarding of a lower band.

Students are encouraged to make use of their full potential and the more creative the structural features they show the better. Nevertheless, the use of variation should not be exaggerated either.

The placement of a performance at a certain band reflects the range of grammatical structures and the level of their correctness within a meaningfully and successfully accomplished communicative task.

The monologues are designed in a way that students at A2 or B1 level have a good chance to succeed and de- monstrate their grammatical range appropriately. Short dialogues are targeted at A2 level. Long dialogues have the potential to elicit B1 language and, as a consequence, also grammatical structures representative of that level.

18 E8 Speaking assessment development

Again, students are allocated one of seven bands.

Band 7 performances should show a variety of grammatical structures and may occasionally go beyond the obvious and expected. However, any enhancement should not make the message sound unnatural or result in an exaggeration of grammatical structures (range for the sake of range). In addition to good range, a rela- tively high degree of grammatical control is expected. A few inaccuracies can occur but they will not impair communication.

Band 5 performances show sufficient range of grammatical structures. Occasional inaccuracies that can impair communication can be tolerated. Performances are unlikely to show risk-taking nor demonstrate that the candidate is attempting to move beyond the basic structures required to meet the prompt expectations. Per- formances at band 5 are typified by an unwillingness to leave the comfort zone of familiar structures.

Band 3 performances feature a limited range of simple grammatical structures. This means that the gramma- tical structures are just enough to achieve successful communication. Mostly they are very simple and re- petitive. Performances at band 3 can be frequently inaccurate and may show basic mistakes. However, these mistakes will not necessarily cause a breakdown of communication.

Band 1 performances feature an extremely limited range of simple structures: structures that are repetitive and follow very simple Subject-Predicate-Object sentence patterns. The structures hardly go beyond the learnt repertoire of beginners. In addition to structural restrictions, band 1 performances show limited control, which frequently causes a breakdown of communication.

Scale Interpretation: Vocabulary

To assess vocabulary in the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment, assessors look at content words – nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs (the correct use of adjectives and adverbs would be assessed under Grammar) –, colloca- tions, and chunks of language that a speaker uses to fulfil a communicative task. The assessment of vocabulary considers the nature of lexis in unplanned speech. And both the range and accuracy will be considered with an emphasis placed on the former.

Vocabulary range refers to the breadth of vocabulary the speakers use in their performances. In the E8 Speaking context, range must be interpreted in relation to the prompt and the constraints that real time performances provide.

It is important to remember that vocabulary items are not limited to single words but include formulaic language, collocations, discourse markers, and chunks of language.

It is not enough for a speaker to use a large number of different words in a performance to achieve a high band in assessment. The words a speaker chooses must be relevant and appropriate to the topic and used in such a way that the message is communicated meaningfully. A good speaker will use vocabulary that is generally accurate enough to formulate even more complex ideas. Speakers who stay in absolutely safe language areas and avoid taking any risk will have less evidence of mistakes, however, it is E8 policy to encourage students to venture out of their safe language zone by rewarding risk taking.

In the assessment of vocabulary the test takers are allocated one of seven bands.

Band 7 performances contain a good selection of content words and phrases that demonstrate that the speak ers are able to express their ideas and occasionally even vary formulations so as not to appear repetitive.

We may well expect one or more expressions to stand out and exceed what we typically expect from students at this level. However, it is possible that occasional, minor inaccuracies could occur.

Band 5 performances contain a sufficient range of mostly high-frequency words that again meet the need to communicate ideas and are generally used accurately. There may be some occasional mistakes, particularly when the speaker is trying to communicate a more complex idea.

Band 3 performances show a limited lexical range containing only a rather narrow repertoire of high- frequency words, but still the simple ideas that are communicated are mostly understandable, even if there is a certain amount of inaccurate vocabulary which can hinder communication.

19 E8 Speaking assessment development

Band 1 speakers with extremely limited lexical competence in English will demonstrate this by including only a few very high-frequency content words that are more often than not inaccurate and inappropriate. We commonly expect band 1 speakers to compensate for their lack in lexical range by interspersing their production with fillers (ermm…, ahh...) or L1 words in order to keep going, thus having the knock on effect of frequently causing a breakdown in communication.

To support teachers in their role as assessor, examples of benchmarked performances are shown in face-to-face training sessions, and provided online (https://moodle.bifie.at/) where they serve as an ongoing resource for teachers.

4.4.3 Rating

As previously mentioned, the rating process has been returned to the heart of the classroom. The subject teacher will almost certainly be assessor and interlocutor as well as being the teacher. Combining these roles, while not simple, will allow the teacher to not only control the process but also to quickly utilise the resultant data to improve the teaching and learning in their classroom.

The complexity of this task should not deter teachers from using the materials offered. In fact, in many coun- tries formal speaking assessments have been/are carried out by the subject teacher in a similar fashion (for an example, see Edexcel, 2012).

To support teachers, there is a range of training material on an online platform (https://moodle.bifie.at/) sup- plemented, in most instances, by face-to-face training sessions. The rubrics are simple and straightforward to use (piloting of the materials has been carried out to confirm this), and the E8 Speaking Rating Sheet has been devel oped with the specific purpose of allowing teachers to quickly and easily rate the real-time performances of their pupils (appendix vii). Videos are also available on the online platform (https://moodle.bifie.at/) de- monstrating how the teacher can arrange their classroom and carry out either a full prompt set assessment, monologue assessment, or dialogues assessment with the rest of the class working independently in the same classroom.

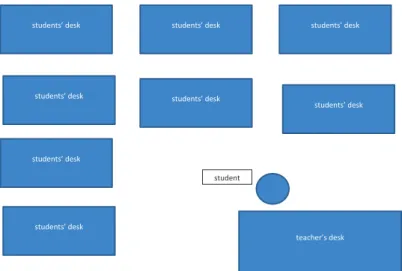

Suggestions as to how the classroom could be organised are shown below:

Figure 2: Possible seating arrangement for monologue assessment

teacher’s desk

students’ desk students’ desk students’ desk

students’ desk

students’ desk

students’ desk

student

students’ desk students’ desk

20 E8 Speaking assessment development

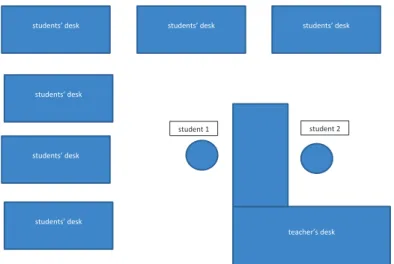

Figure 3: Possible seating arrangement for full assessment and dialogues assessment

As the rater (assessor) will be the subject teacher, rater variability and therefore rater judgements will probably show considerable divergence. Myford and Wolfe (2003, 2004) have highlighted key aspects of rater effects including the ‘leniency/severity’ effect, the ‘halo’ effect, and the ‘bias’ effect, among others (Taylor and Galaczi, 2011: 209).

Rater training is seen as an important counter to these effects and a precursor for the standardisation of rating.

As part of the purpose of the new assessment design is to embed the assessment of speaking in the classroom with the teacher taking the lead in the teaching and assessment of speaking, the training for the role of inter- locutor and assessor has also been devolved and moved closer to the classroom. While this has the obvious benefit of putting the teacher at the heart of the process, it will also have a negative impact upon standardisation, and although attempts will be made to lessen this negative impact through a cascade training model and online training and support, the results will no longer be of sufficient validity to be reported on a national level, and will instead be used solely to improve the teaching and learning of speaking in the classroom. One could argue, that the focus has simply returned to where it should always have been: in the classroom where the teachers and learners are.

4.4.4 Assessor/Interlocutor training

A. The training of facilitators – who will then cascade information to subject teachers – led by members of the E8 Speaking Team

Part 1: Face-to-face training including: prompt sets and prompt interpretations, interlocutor behaviour and guidelines, practice session with peers, the assessment scale.

Part 2: Online training using the online platform: theoretical background to speaking in the classroom; the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment; the role of the interlocutor and assessor; the E8 Speaking Assessment Scale; using the E8 Speaking Assessment Scale and the accompanying Rating Sheet; working with the data.

Part 3: Face-to-face training including: feedback from the online course, improving the teaching of speaking in the classroom, preparing to share the knowledge with other English teachers.

B. Training of subject teachers by facilitators/members of the E8 Speaking Team

Face-to-face training: this may vary depending on the setting and the audience (for example, training in a departmental meeting for the subject teachers in a school will differ from the training offered in a university setting or for formal in-service training for a group of teachers from different schools/school types). How- ever, we would expect the following to be covered to a certain degree: prompt sets and prompt interpreta- tions, interlocutor behaviour and guidelines, the role of the assessor, the E8 Speaking Assessment Scale, improving the teaching of speaking in the classroom.

Online training using the online platform as above.

teacher’s desk

students’ desk students’ desk students’ desk

students’ desk

students’ desk

students’ desk

student 2

student 1

21 Feedback

C. Updates via the online platform

The online platform will be updated on an annual basis with prompt sets being added to allow teachers to use new materials for the new academic year. While it is likely that materials will be recycled new items will also be added.

5 Feedback

As no formal standardisation or moderation processes are available, assessor reliability cannot be guaranteed.

For this reason, results are only made available to the teacher and, presumably, their pupils. The data generated should be used to improve the teaching and learning of speaking in that classroom, and could inform pupils’

report grades, but it cannot be used for more general purposes.

To assist teachers in their analysis of results, they are provided with an assessment tool via the online platform.

Once the teacher has made his/her assessment of a pupil’s performance, these results can be entered into the Data Assessment Tool (https://moodle.bifie.at/) which can then offer a quick analysis of the figures: showing how groups of students as well as individual students perform in relation to the four dimensions of the E8 Speaking Assessment Scale.

This information then directs the subject teacher to material (both further reading and classroom ready resources) that can be utilised to make immediate improvements to the teaching and learning of speaking in the classroom (https://moodle.bifie.at/). It is hoped that this simple tool will assist in the intended purpose of the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment: the improvement of the teaching and learning of speaking in the classroom. Washback should occur at the classroom level. However, to ensure that this washback effect also impacts at the curriculum level, we expect that mechanisms will be put in place for further dialogue between individual subject teachers and the test (assessment) designers and curriculum developers of the future (indeed, the online platform includes a comments section to encourage such dialogue).

6 Assessing E8 Speaking – a summary

6.1 Purpose of the assessment

The E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment, as it now takes place in the classroom and is conducted by the subject teacher, should result in a timely improvement of the teaching and learning of speaking in the classroom as feedback from the assessment will be immediate.

6.2 Description of assessment participants

While the target audience is pupils of the 8th school year in both AHS and NMS settings in Austria, the deci- sion of how, when, and with whom the assessment process will be carried out lies with the subject teacher.

6.3 Test level

The difficultly level of the test is supposed to encompass levels A2 to B1 in the CEFR.

22 Assessing E8 Speaking - a summary

6.4 Test Construct

Since the pupils’ communicative competence will be assessed, the most significant competences needed for speaking have to be defined:

an appropriate response to the task, the adequate use of devices to communicate clearly, and turn-taking (Task Achievement & Communicative Skills)

the ability to produce natural speech by using standard pronunciation and stress and by producing fluent utterances (Naturalness of Speech)

the students’ linguistic competence demonstrated in the adequate use of a range of grammatical structures and the choice and accuracy of vocabulary (Grammar; Vocabulary).

Moreover, the Construct Space, used to construct tasks, has to be specified (appendix ii). It lists the E8 BIST descriptors, the topics from the ANCFL, the spoken text types, the speaking purpose/communicative functions, the context/audience, and the CEFR descriptors with which the E8 BIST descriptors can be linked.

6.5 Structure of the assessment

The assessment is designed to be carried out and assessed by the subject teacher (potentially with assistance from a classroom assistant and/or second teacher). The subject teacher should have completed the E8 Speaking Classroom Assessment training (at minimum the online training course).

The subject teacher has the choice of the following formats:

1. full prompt set including 2 monologues, 1 short dialogue and 1 long dialogue 2. monologue prompt set including a minimum of 2 monologues

3. dialogues prompt set including 1 short dialogue and 1 long dialogue.

They should follow the scripts given in the prompt sets and can use the advice offered in this technical report and on the online platform regarding setting, procedures etc.

6.6 Time allocation

The prompt sets include time allocations for pupils to plan their performance(s) when necessary (monologue and long dialogue) and also clearly show the time allowed for each performance. Subject teachers should take these timings into account when planning the lessons in which assessments will take place. As a guide:

a monologue requires 1 minute for planning and 2 minutes for the performance

a short dialogue requires 1–2 minutes in total (no planning is necessary)

a long dialogue requires 1 minute for planning and 5 minutes for the performance.

6.7 Rubrics

All rubrics are in English. In order to be easily understandable for the students and easy to use for the subject teachers, the language level does not exceed CEFR level A2 and instructions are simple and repetitive.

6.8 E8 Speaking Assessment Scale

The assessment scale has been slightly re-designed to align with the E8 Writing Rating Scale and for ease of use for subject teachers. An E8 Speaking Rating Sheet (appendix vii) has also been developed to assist the subject teacher in their role as assessor. As before, descriptors for each of the 4 dimensions are given for bands 1, 3, 5, and 7. Bands 2, 4, and 6 are awarded for performances slightly above or below the adjacent level.

23 Conclusions and recommendations

6.9 Prompt sets

Prompt sets have been developed and piloted by the E8 Speaking Team. Repair questions have been provided for use by the interlocutor in cases of communication breakdown to encourage the student(s) to continue speaking.

7 Conclusions and recommendations

In Figueras’ (2014: 15) report, she discussed possible further developments. Included were:

The need to stress the benefits for teaching and learning English speaking at schools. It is hoped that the transfer of responsibility of the assessment of E8 Speaking to the classroom and subject teacher, with the support of the online platform and a simple diagnostic tool, will accelerate this process.

The issue of sustainability. The training of facilitators, who can, using a cascade model, further disseminate the assessment model, coupled with the provision of an ongoing online platform should help with the prop- agation and longevity of the project.

8 Bibliography

Bachman, L.F. (1990) Fundamental Considerations in Language Testing. Oxford: OUP.

Bagarić, V. & Djigunović, J. M. (2007) Defining Communicative Competence. Metodika, 8 (1), 94–103.

Bundesministerium für Bildung (2000) Lehrplan AHS Unterstufe Lebende Fremdsprache [Online]. Available from: https://www.bmb.gv.at/schulen/unterricht/lp/lp_ahs_unterstufe.html [Accessed 25 July 2017].

Broek, S. & van den Ende, I. (2013) The Implementation of the Common European Framework for Languages in European Education Systems Study. Brussels: European Parliament. Available from: http://www.europarl.europa.

eu/studies [Accessed 15 July 2017].

Canale, M. & Swain, M. (1980) Theoretical Bases of Communicative Approaches to Second Language Teaching and Testing. Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 1–47.

Cambridge English (2016) Key for Schools Handbook for Teachers. Cambridge English. Available from: http://

www.cambridgeenglish.org/images/168174-cambridge-english-key-for-schools-handbook-for-teachers.pdf [Accessed 25 July 2017].

Cambridge English (2016) Cambridge English Preliminary Handbook for Teachers. Cambridge English. Avail- able from: http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/images/168150-cambridge-english-preliminary-teachers-hand- book.pdf [Accessed 25 July 2017].

Chomsky, N. (1965) Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. (Cited in Canale and Swain, 1990: 3).

Council of Europe (2001) Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, Teaching, Assessment. Cam- bridge: Cambridge University Press.

Edexcel (2012) GCSE Spoken Language: Controlled Assessment Teacher Support Book. Pearson. Available from:

https://qualifications.pearson.com/content/dam/pdf/subject-updates/languages/GCSE-Controlled-Assess- ment-TSB%20MFL%20_Speaking_%20finalised.pdf [Accessed 18 July 2017].

English Vocabulary Profile. Available from: http://vocabulary.englishprofile.org/staticfiles/about.html [Accessed 25 July 2017].