Essays on the Organizational Effects of Identification, Wage Expectations, and

Fairness Concerns

Inauguraldissertation zur

Erlangung des Doktorgrades der

Wirtschafts-und Sozialwissentschaftlichen Fakultät

der

Universität zu Köln

2019

vorgelegt von

Lea M. Petters, M.Sc.

aus Karlsruhe

Korreferent: Professor Dr. Matthias Heinz Tag der Promotion: 17.12.2019

Danksagung

Mein größter Dank geht an meinen Doktorvater, Dirk Sliwka, dessen fachliche Expertise und intellektuelle Schärfe mich immer wieder beeindrucken. Seine Offenheit gegenüber neuen Ansätzen und die intrinsische Motivation die Diszi- plin voranzubringen machen ihn, neben seiner bescheidenen und freundlichen Persönlichkeit, zu einer großen Inspirationsquelle. Vielen Dank für die fach- liche und persönliche Unterstützung sowie die kooperative Zusammenarbeit!

Darüberhinaus möchte ich Marina Schröder, die meine Promotionszeit maßge- blich mitgeprägt hat, von Herzen danken. Als Koautorin, Mentorin und weib- liches Rollenvorbild, durfte ich unglaublich viel von ihr lernen und bin sehr dankbar für die gemeinsame Zeit in Köln. Auch Patrick Kampkötter möchte ich sehr gerne für die ständige Ansprechbarkeit, Geduld und die insgesamt sehr an- genehme Zusammenarbeit danken, die nicht zuletzt seiner netten Persönlichkeit geschuldet ist. Matthias Heinz danke ich für die Übernahme des Korreferats sowie für seine wertvollen Ratschläge, seine konstruktive Kritik und seine an- genehme und zugängliche Art, die ebenfalls meine Zeit am Lehrstuhl so positiv gestaltet hat.

Des Weiteren möchte ich meinen lieben Kolleginnen und Kollegen, die mich über meine Promotionszeit begleitet haben, bedanken. Einerseits, möchte ich dem LPP-Team für die angenehme Zusammenarbeit danken, allen voran Su- sanne Steffes, aber auch den Teammitgliedern seitens des IAB, Philipp Grunau und Stefanie Wolter. Andererseits, wäre die Zeit am Lehrstuhl natürlich nicht so einmalig gewesen, hätten mich nicht so viele nette Kolleginnen und Kolle- gen begleitet: Agne Kajackaite, Christoph Groß-Bölting, Jakob Alfitian, Jesper Armouti-Hansen, Katharina Laske, Lisa Lenz, Mira Fischer, Sebastian Butschek, Sidney Block, Timo Vogelsang, Viola Ackfeld und alle Mitstreiter am Irlenbusch Lehrstuhl - vielen Dank für die angenehme und kooperative Arbeitsatmosphäre, die schönen Sommer- und Weihnachtsfeiern und die vielen interessanten und lustigen Gespräche beim Mittagessen! Vielen Dank auch an Matthias Kaldorf für die zahlreichen Diskussionen beim Mittagessen und Kaffee sowie die ein oder andere gemeinsame Beachvolleyballsession. Ein großes Dankeschön geht natürlich auch an alle aktuellen und ehemaligen Hiwis für die Unterstützung jeglicher Art: Hannah Tornow, Katharina Arnhold, Leonie Kern, Paula Wet- ter, Rebecca Radermacher, Ruth Neeßen, Tarek Khellaf, Theresa Hitzemann, Tobias Danzeisen und alle, die ich hier vergessen habe, sowie Kristen Clarke für die regelmäßige Korrektur meiner Grammatik- und Kommafehler.

Neben der fachlichen Unterstützung, hat natürlich auch mein privates Umfeld maßgeblich zum Abschluss dieser Arbeit beigetragen. Allen voran möchte ich meinen Eltern von Herzen für ihre jahrelange Unterstützung und Zuspruch in jeglicher Form und den so wichtigen Zusammenhalt in den verschiedenen Leben- sphasen danken. Danke, dass ihr immer an uns glaubt und uns unterstützt!

Darüber hinaus haben mich auch meine beiden Geschwister Kira und Gero auf diesem Weg stets begleitet und sind von großer Bedeutung für mich. Gero, vielen Dank für deine entspannte und liebenswürdige Art, es freut mich so sehr, dass du nun auch den Weg in die Domstadt gefunden hast! Danke, Kira, dass du immer für mich da bist und Schwester, Reisegefährtin, Freundin und Mannschaftkolle- gin in einer einzigartigen Person vereinst!

danken, der mich auch in schwierigen Phasen aufgebaut hat und immer ein of- fenes Ohr für mich hatte. Mein besonderer Dank geht an Anika, Kim, Nora, Magda, Marius, Micha, Sheila, die gesamte Beachvolleyballclique und alle an- deren, die mich in dieser Zeit unterstützt haben. Außerdem möchte ich hier auch die beste Volleyballmannschaft Kölns nicht unerwähnt lassen. Liebes AVC- Team, danke für diese unglaublich positive Energie und die einzigartige Mis- chung, die unser Team so besonders macht! Vielen Dank auch an die Familie Jung, Angela und Anne-Sophie, für die so herzliche und einladende Aufnahme in den erweiterten Familienkreis.

Zuallerletzt möchte ich meinem Partner und besten Freund, Philipp, danken.

Vielen Dank, dass du mich besonders in dieser finalen Phase immer wieder so geduldig durch aufbauende Worte, Korrekturlesen und konstruktive Kom- mentare unterstützt hast und ich mich immer auf dich verlassen kann.

Contents

1 Introduction 1

2 Employee Identification and Wages 7

2.1 Introduction . . . 7

2.2 The Model . . . 10

2.2.1 Analysis . . . 10

2.2.2 Wage Bargaining . . . 11

2.2.3 Job Search and External Offers . . . 12

2.2.4 Predicted Patterns . . . 14

2.3 Data and Descriptive Statistics . . . 15

2.4 Results . . . 16

2.4.1 Job Satisfaction, Wages, and Affective Commitment . . . 16

2.4.2 A Proxy for Work Effort . . . 18

2.4.3 Predicting Wage Growth . . . 20

2.4.4 Job Search and Turnover . . . 23

2.4.5 Wage Growth with External Offer . . . 25

2.5 Conclusion . . . 27

2.6 Appendix to Chapter 2 . . . 28

3 Negative Side Effects of Affirmative Action 37 3.1 Introduction . . . 37

3.2 Experimental Design . . . 39

3.3 Results . . . 43

3.3.1 Biases in Peer-reviews . . . 43

3.3.2 Tokenization of Affirmed Winners . . . 47

3.3.3 Spillover Effects of Quotas . . . 48

3.4 Conclusion . . . 50

3.5 Appendix to Chapter 3 . . . 52 i

4 The Hidden Cost of Training 69

4.1 Introduction . . . 69

4.2 Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses . . . 72

4.3 Evidence from Field Data . . . 73

4.4 Experimental Evidence . . . 76

4.4.1 Experimental Design . . . 76

4.4.2 Results . . . 80

4.5 Conclusion . . . 88

4.6 Appendix to Chapter 4 . . . 89

List of Tables

2.1 Job Satisfaction and commitment . . . 17

2.2 Sick days and unpaid overtime . . . 19

2.3 Wage growth and commitment . . . 22

2.4 Job search, turnover, and commitment . . . 24

2.5 Wage growth and commitment with external offer . . . 26

2.6 Summary statistics . . . 31

2.7 Wage growth and commitment with control for engagement . . . 33

2.8 Wage growth and engagement . . . 34

2.9 External offer wages and commitment . . . 35

2.10 Job search, turnover, and commitment with control for personal- ity traits . . . 36

3.1 Regression analysis peer-reviews provided . . . 44

3.2 Regression analysis peer-reviews provided by rater type . . . 46

3.3 Regression analysis dictator game . . . 49

3.4 Summary statistics . . . 61

3.5 Regression analysis peer-reviews provided by rater type with lab raters as control for independent ratings . . . 62

3.6 Regression analysis peer-reviews provided – all treatments com- bined . . . 63

3.7 Regression analysis independent ratings . . . 64

3.8 Regression analysis peer-reviews provided by rater type with con- trol for perceived procedural fairness . . . 65

3.9 Regression analysis peer-reviews provided by rater type – gender differences . . . 66

4.1 Training and wage expectations . . . 75

4.2 Fair wage norm . . . 82 iii

4.3 Time invested . . . 84 4.4 Decoded words . . . 87 4.5 Summary statistics WeLL . . . 89 4.6 Training and wage expectations (alternative specification) . . . . 90 4.7 Summary statistics experiment . . . 101 4.8 Decoding time . . . 102 4.9 Decoding time - heterogenous effects . . . 103 4.10 Time invested - heterogenous effects (alternative specification) . 104 4.11 Decoded words - heterogenous effects (alternative specification) . 105

List of Figures

2.1 Wage growth for employees by degree of affective commitment . 20

3.1 Set of materials . . . 40

3.2 Examples of illustrations . . . 41

3.3 Treatments . . . 42

3.4 Fraction of affirmed winners . . . 48

4.1 Experimental structure . . . 77

4.2 Screenshot real-effort decoding task . . . 78

4.3 Treatments . . . 80

4.4 Screenshot fair wage elicitation . . . 93

4.5 Screenshot training . . . 94

v

Chapter 1

Introduction

“To understand how economies work and how we can manage them and prosper, we must pay attention to the thought patterns that

animate people’s ideas and feelings, their animal spirits.”

George A. Akerlof and Robert J. Shiller (2009)

This thesis deals with behavioral factors that critically influence the outcomes of organizational practices. Based on theory, we use experimental and field data to investigate to what extent employees’ decisions are driven by psychological motives such as emotional attachment, expectations, and fairness perceptions.

We show that behavioral mechanisms play a crucial role in determining the consequences of organizational practices, often affecting them in unexpected ways.

Traditional economics has evolved around the idea of an economic agent that is rational, forward-looking, has unlimited cognitive abilities and only cares about his own monetary payoff - the homo oeconomicus. Although researchers were well aware early on that this concept constitutes a very simplified model of hu- man nature, it took until the second half of the twentieth century for behavioral economics to establish itself as a subfield of the economic discipline (Dohmen 2014). The ever-growing empirical evidence contradicting the neoclassical view contributed significantly to the advancement of the behavioral approach, which aims at explaining these phenomena (Dhami 2016). This new strand of litera- ture explicitly models psychological factors as determinants of individual eco- nomic decision-making, giving credit to heterogenous, time-inconsistent, and other-regarding preferences, biased beliefs, as well as bounded rationality. Since human behavior is at the heart of most questions in labor and particularly in personnel economics, the models and methods of behavioral economics have received increased attention in this field within recent decades (Gächter and Fehr 2002; Charness and Kuhn 2011; List and Rasul 2011; Babcock, Congdon, et al. 2012). When looking at micro-level interactions between employers and employees or amongst employees respectively, the importance of psychological factors for individual behavior becomes especially evident and cannot be ne- glected (Dohmen 2014). Therefore, understanding the factors that influence

1

human decision-making and accounting for this when implementing managerial practices, is crucial for organizations.

In the following chapters, we shed some light on human reactions to manage- rial measures. We do so by examining behavioral mechanisms that lead to ambiguous and potentially adverse organizational effects. One channel we are looking at is the employee’s identification with the employer. In their seminal paper, Akerlof and Kranton (2000) are the first to introduce the concept of identity into the individual’s utility function. Later work transfers this concept to the organizational context and establishes identification with the employer as a major source for employee motivation (Akerlof and Kranton 2005; Besley and Ghatak 2005). We extend the literature by considering the role of identification in employees’ job search and wage bargaining behavior and their implications for wage growth. Additional behavioral mechanisms we are interested in are fairness concerns (Konow 1996; Bolton and Ockenfels 2000; Cappelen et al.

2007) and their implications for organizational interactions (see Fehr, Goette, and Zehnder 2009, for an overview). Based on previous findings that show that the acceptance of affirmative action policies depend on their perceived fair- ness (Harrison et al. 2006; Balafoutas, Davis, and Sutter 2016; Ip, Leibbrandt, and Vecci 2018), we study how differences in procedural fairness induced by affirmative action and/or ex-ante disadvantages affect peer-review behavior in competitive settings. Lastly, building on the work by Akerlof and Yellen (1990) that introduced the concept of the fair wage-effort hypothesis, we consider the role of training participation in fair wage expectations and its effect on sub- sequent effort provision and productivity. All mechanisms we investigate deal with non-standard preferences, i.e., social comparisons and social preferences (DellaVigna 2009). The presented research, therefore, falls into the subfield of behavioral economics that challenges the neoclassical assumption that individu- als only take their own absolute payoff into account when deciding in economic situations.

Our research features a mix of different methods combining theoretical argu- ments with evidence from field and experimental data. The combination of methods allows us to analyze a problem from different perspectives and to gather evidence from complementary sources, thus giving a more complete picture of the question of interest (Dhami 2016; Kampkötter and Sliwka 2016). Theoreti- cal considerations provide a structured and mathematically formalized approach to think about an economic problem. Furthermore, it enables the derivation of clearly defined hypotheses with respect to the research question in focus.

Based on the theoretical foundations, empirical field data can give insights as to whether the predicted patterns can be observed in the real world. While field data are excellent to detect whether these patterns can be generalized to environments where different mechanisms are at play and many forces interact, it is often difficult to control for unobserved factors and retain clear causal evi- dence. This is where experimental methods have their strengths (Gächter and Fehr 2002; Dohmen 2014). Experiments can establish causal relationships by implementing truly exogenous variation in a very controlled environment. Fur- thermore, using these methods, researchers can collect data on a very granular and detailed level, that can hardly be found in field data. This allows specific behavioral mechanisms to be uncovered and is therefore particularly well suited to test theoretical predictions (Falk and Heckman 2009; Charness and Kuhn

2011; Ludwig, Kling, and Mullainathan 2011). In the following paragraphs, we shortly summarize the contents and the individual contributions of the different chapters.

Chapter 2 studies the role of employees’ identification with their employer as a component of match quality for determining job satisfaction, effort provision, job search, bargaining behavior, and resulting wage growth.1 Previous research has mainly focused on outcomes of match quality (e.g., wage, tenure, produc- tivity), instead of trying to explicitly measure its components. In a first step, we analyze a stylized formal model, which integrates the emotional attachment to the employer into the employee’s utility function. In line with previous re- sults in the literature (Akerlof and Kranton 2000; Besley and Ghatak 2005), our theoretical framework predicts that a higher identification with the employer is related to (i) a lower marginal utility from wages and (ii) higher work effort.

Furthermore, we consider wage bargaining behavior and identify two different channels through which the employee’s emotional attachment can affect wage growth. In theory, there is a trade-off between a “compensating wage differ- ential” effect, i.e., the employer can provide lower wage growth because the employee actually enjoys working for the employer, and a “motivation” effect, i.e., the employer would be willing to grant higher wage growth as the employee exerts higher effort for a given wage level. The relative bargaining position de- termines which of the two effects dominates. When the employer’s bargaining power is sufficiently high, the model predicts that (iii) employees with a higher emotional attachment experience lower wage growth. This is also driven by (iv) lower search efforts on the side of the employee and thus a lower likelihood of obtaining an external offer. However, when the employee has obtained an external offer, the bargaining situation reverses and an employee with higher identification can (v) negotiate a higher wage growth since he is more valuable to the organization.

As a second step, we test the predicted patterns using a novel employer-employee panel dataset. We take advantage of a validated survey measure of “affective commitment” (Meyer and Allen 1991) as a proxy for employee identification.

Consistent with our theoretical model, we find that, for committed employees, absolute wage is significantly less predictive for job satisfaction. Additionally, we observe that employees with higher commitment have significantly fewer absence days and more hours of unpaid overtime, which represent our effort measures. Moreover, higher commitment predicts a lower wage growth in the future and is associated with a lower propensity to search for alternatives, receive an external offer, and to quit the current employment voluntarily. However, we also find evidence that employees can successfully exploit their higher threat point when they have obtained an external offer, thus resulting in increased wage growth. This relationship seems to be even more pronounced for more committed employees.

Our research adds to the current literature by providing a theoretical frame- work that models identification as a component of non-monetary match quality which not only affects job satisfaction and effort provision, but also influences job search behavior and thus wage trajectories. Furthermore, we present evi-

1Chapter 2 is joint work with Patrick Kampkötter and Dirk Sliwka and based upon Kamp- kötter, Petters, and Sliwka (2019)

dence for the predictive power of a validated survey measure, thereby empha- sizing the empirical relevance of employee identification for employer-employee relationships.

In chapter 3, we experimentally analyze the effect of quota interventions on peer-review behavior.2 While affirmative action policies in the form of quotas are increasingly used by regulators to promote the representation of minority groups in leading positions in management and academia (Wallon, Bendiscioli, and Garfinkel 2015; European Commission 2016), the scientific evidence on the effectiveness of quota interventions remains mixed (Beaman et al. 2009;

Niederle, Segal, and Vesterlund 2013; Leibbrandt, Wang, and Foo 2018). Our study gives insights into potential negative side effects and shows that quotas can lead to distortions in subjective peer-reviews, and therefore harm the group that is supposed to benefit from the quota.

We study the impact of a quota intervention in a situation where subjective peer-reviews are a crucial determinant of the career advancement of an indi- vidual. Such situations frequently arise in business environments where hiring and promotion decisions are based on subjective evaluations by (potential) su- pervisors or co-workers. They also play an essential role in the academic pro- fession where peer-reviews are decisive for publication success, research funding or tenure. Since the introduction of a quota substantially changes the com- petitive structure within a tournament, such an intervention might also affect peer-review behavior. On the one hand, a quota increases competition among the group which is affirmed under the quota regime and therefore provides an incentive for this group to evaluate other affirmed peers less favorably. On the other hand, by design a quota favors the affirmed group over the non-affirmed group and thus creates inequality within the tournament, which also may lead to a reaction in peer-review behavior due to procedural fairness concerns. These fairness concerns, however, might be mitigated depending on the justification behind the introduction of the quota (Balafoutas, Davis, and Sutter 2016; Ip, Leibbrandt, and Vecci 2018).

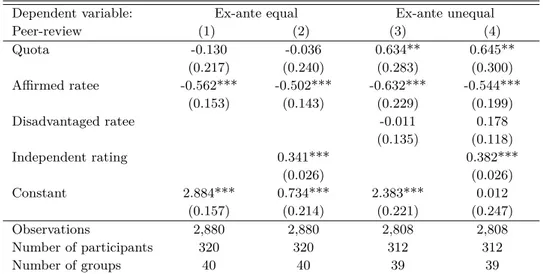

To shed light on these questions, we conduct a real-effort tournament exper- iment, in which we randomly assign participants to affirmed or non-affirmed types. Participants are asked to work on a creative task (Laske and Schröder 2016) and subsequently to evaluate the performance of the three other peers within their group. The outcome of this peer-review process determines which participants win one of two prizes. In a two-by-two design, we vary (i) whether or not a quota is implemented and (ii) whether or not the affirmed group faces ex-ante procedural disadvantages. When a quota is implemented, one of the two prizes is reserved for the best-performing participant within the affirmed group.

In treatments with ex-ante inequality, affirmed participants face procedural dis- advantages in form of a shorter working time to fulfill the task. This ex-ante disadvantage might serve as a potential justification for the introduction of a quota.

Our results show that quotas have a significant impact on peer-review behav- ior. First, we find that quotas affect the overall level of peer-reviews provided.

This effect, however, depends on the perceived procedural fairness which varies

2Chapter 3 is joint work with Marina Schröder and based upon Petters and Schröder (2019)

between the two quota treatments. In our research design, the absolute level of peer-reviews has no impact on tournament outcomes since both affirmed and non-affirmed groups are affected equally. In real-life applications, though, this might lead to negative effects on overall motivation and work climate, and might distort evaluations when levels are compared across different environments. Sec- ond, we show that quotas lead to systematic biases in peer-reviews against the affirmed group. They receive significantly less favorable peer-reviews relative to their non-affirmed peers. This second effect is not related to the perceived procedural fairness since it remains robust across both quota treatments. In- stead, these distortions seem to be a result of the enhanced competition among affirmed inviduals under the quota regime as they are fully driven by peer- reviews provided by affirmed individuals to other affirmed peers. This result has strong implications for the effectiveness of quota interventions. Unfavor- able peer-reviews might hinder the career advancement of the affirmed group and thus counteract the initial goal of the the quota intervention. Lastly, we study spillover effects of quotas on giving in an additional dictator experiment after the conclusion of the main experiment. We find that a quota in the previ- ous experiment significantly reduces altruistic behavior among individuals that were affirmed before. Therefore, we provide evidence of negative spillover effects of quotas to non-competitive environments. The results indicate that a quota regime might actually impede the establishment of social networks and mutual support within the affirmed group, thereby undermining another goal behind the introduction of affirmative action.

Our research points towards negative side effects of quota interventions that mainly affect the group which was supposed to benefit from preferential treat- ment. Therefore governments and organizations, which seek to implement quo- tas in order to promote minority groups, need to pay special attention to poten- tial adverse effects of such interventions as they might render them ineffective.

Chapter 4 presents a further behavioral mechanism that impedes the initial goal of an organizational measure.3 We study the effect of training participation on employees’ fair wage expectations, effort provision, and finally productivity.

Firms invest in training to increase the skills and, through this, the produc- tivity of their employees. We theoretically argue that the relationship between an increase in skills and higher productivity might not be as clear-cut since behavioral factors might also play a role. Given that labor productivity is de- termined by two factors, namely skills and effort, training should increase the employee’s skill level and thus ceteris paribus have a positive impact on produc- tivity. Following the fair wage-effort hypothesis as introduced by Akerlof and Yellen (1990), the second component, effort, can be described as a function of wage relative to some “fair wage”. If the actual wage is equal to or exceeds this fair wage, maximum effort is provided by the employee. If, however, the actual wage falls below what is perceived as fair, the model predicts that the employee feels unfairly treated and, as a consquence, reduces effort. We argue that the wage the employee perceives as fair depends on the employee’s skill level and thus is also affected by training. Therefore, we hypothesize that training not only has a direct effect on skills, which positively affects productivity, but also an indirect effect on effort. This indirect effect works through the adjustment of

3Chapter 4 is based upon Petters (2019)

the fair wage, which - for a constant wage - has a negative effect on overall pro- ductivity. Training participation can therefore cause two countervailing effects, so that the net effect on productivity is ambiguous.

We use an extensive linked employer-employee survey dataset to study the re- lationship between training participation and future wage expectations. In our analyses, we apply an identification approach introduced by Leuven and Oost- erbeek (2008). This approach exploits an alternative control group of accidental training non-participants to account for the potential selection bias into train- ing, which would lead to biased estimation of the training effects. To be able to exogenously assign training and wages, as well as to explicitly measure skills, effort, and productivity, we conduct an additional laboratory experiment. We apply a newly developed experimental design which uses an employer-employee gift exchange setting. Employees work for two working phases for a fixed wage on a real-effort decoding task that benefits the employer. In the first working phase, all employees face the same working conditions, thus serving as a form of control phase. Thereafter, we vary (i) whether or not an employee receives training between the two working phases, and (ii) whether or not an employee receives a wage increase for the second working phase. Both after the first work- ing phase and before the second working phase, we elicit a measure of the fair wage.

The analyses of our field dataset indicate that employees hold higher future wage expectations as a result of training participation. Our experimental re- sults confirm this relationship and give additional insights into the behavioral mechanisms behind training participation. We find that even though training is effective in increasing the skills and thus productivity potential of an employee, this does not neccessary translate into increased productivity for the employer.

Instead, our results show that trained employees negatively adjust effort both on the extensive and intensive margin. Additional analyses reveal that, in line with our theoretical considerations, the difference between the actual and the perceived fair wage is a determinant of whether or not an employee releases his productivity potential. Thus, these results indicate that fairness concerns can impair the positive productivity effects of training.

Our results have broad implications for organizational training investments.

We show that behavioral factors play an important role in determining whether training is effective in increasing productivity. Not accounting for these channels might lead to lower than expected returns on training and thus result in reduced human capital investments by firms.

The research presented in this thesis demonstrates the importance of psycholog- ical factors for employer-employee interactions and the outcomes of managerial measures. We show that it is critical to understand the behavioral mechanisms at play in order to achieve the intended results and potentially take precaution- ary actions to prevent adverse effects.

Chapter 2

Employee Identification and Wages 1

2.1 Introduction

In labor economics, it has often been stressed that an employee’s decision on whether to stay or move to a different employer not only depends on wages, but also on non-monetary aspects of the job match (e.g., Sullivan and To 2014).

In most of the literature, however, this “match quality” is treated as an unob- served black box and is only proxied by directly observable outcomes such as wages, tenure, firm size, worker skills or productivity (W. Johnson 1978; Jo- vanovic 1979; Mortensen 1988; Bowlus 1995; Abowd, Kramarz, and Margolis 1999; Gaure, Røed, and Westlie 2012; Eeckhout 2018; Eeckhout and Kircher 2018). This chapter opens part of this black box by studying one important component of match quality: employees’ emotional identification with their em- ployer. First, we analyze a formal model in which an employee works for an employer and is characterized by the degree to which he identifies with the in- cumbent employer. We assume that a higher identification increases the extent to which the employee internalizes the employer’s payoff. In line with Akerlof and Kranton (2005) or Besley and Ghatak (2005), in such a framework, a higher identification naturally leads to higher work efforts. Moreover, the model pre- dicts that an employee’s well-being depends on his wage to a lesser extent when he identifies more strongly with his employer. In a next step, we consider wage negotiations and show that when the employer has sufficiently high bargaining power or when there is no moral hazard problem, wages are downward slop- ing in affective commitment. This constitutes essentially a “compensating wage differential” effect (e.g., Rosen 1986) as well known from the literature on pub- lic sector and non-profit motivation (Delfgaauw and Dur 2007; Delfgaauw and Dur 2008): an employee who attaches some intrinsic value to staying with the employer has a weaker bargaining position and thus stays with the firm at a lower wage level. However, the picture changes when the employee has a higher

1This chapter is joint work with Patrick Kampkötter and Dirk Sliwka and based upon Kampkötter, Petters, and Sliwka (2019)

7

threat point by having obtained an external offer and chooses an unobservable work effort. In this case, a higher identification with the firm has a higher value for the employer2 as such an agent will exert higher efforts ex-post. In turn, a more “committed” employee will be able to negotiate a higher wage. Hence, the model does not make a clear prediction on the effect of employee identification on wage growth as there are two countervailing effects. However, the model does predict that,conditional on effort,wage growth should be downward slop- ing in affective commitment. Additionally, conditional on having an external offer, i.e., all bargaining power lies with the employee, more committed employ- ees should be able to negotiate higher wages, and thus wage growth should be upward sloping in affective commitment.

Second, to test the predictions generated by this model, we analyze a novel linked employer-employee dataset. In order to quantify employees’ identification with their employer, we use a standard survey measure of emotional attachment from the literature in organizational psychology (affective organizational com- mitment, see e.g., Meyer and Allen 1991) to predict future wage growth and search behavior in the labor market.3 We find that (i) the predictive power of the wage level for job satisfaction is significantly weaker for employees with a higher affective commitment; (ii) a higher affective commitment is associated with higher work efforts, i.e., a lower number of absence days and more unpaid overtime; (iii) a higher affective commitment in period t predicts a lower wage growth in t+1; (iv) the effect is more pronounced when we control for a mea- sure of employee effort; (v) a higher affective commitment is associated with a lower likelihood that an employee searches for another job, receives an external outside offer or voluntarily quits his job with his incumbent employer; and (vi) employees that have obtained an outside offer can negotiate significantly higher wage growth with their incumbent employer. In addition, we find evidence that this relationship tends to be even stronger for employees with higher affective commitment. This indicates, that employees with higher affective commitment are able to overcome the “compensating wage differential” effect by presenting a higher threat point in the form of an outside offer. However, they do so less often.

We contribute to the existing research in several ways. Even though the la- bor economics literature has considered the quality of the job match as an important determinant of worker satisfaction and retention (Bowlus 1995; Fer- reira and M. Taylor 2011; Barmby, Bryson, and Eberth 2012), only few studies have attempted to measure aspects of match quality explicitly (see Fredriks- son, Hensvik, and Skans 2018, for an example of the latter). With our focus on employee identification as an important non-monetary aspect of job match quality4, we add to the discussion in labor economics and relate to concepts

2In this respect, identification underlies similar mechanisms as firm-specific human cap- ital, which is also only valuable for the incumbent employer but not for potential external employers, and thus has strong implications for counteroffers by the incumbent employer once an external offer is available (see e.g., Yamaguchi 2010; Lazear 2012).

3Bömer and Steffes (2019) study supervisory support as a component of match quality, which determines employees’ job search behavior using the same dataset.

4In contrast to rather stable cognitive skills and personality traits (or non-cognitive skills), i.e., “personal attributes not thought to be captured by measures of abstract reasoning power”

(Heckman and Kautz 2012, p. 452), which the previous literature has identified as impor- tant factors for labor market success (e.g., Heckman, Stixrud, and Urzua 2006), emotional

discussed in the fields of behavioral economics, organizational psychology, and management. With the emergence of the behavioral economics literature and the consideration of social preferences in economic decision-making (Fehr and Schmidt 1999; Bolton and Ockenfels 2000; Charness and Rabin 2002), also the concept of (group) identity has been introduced into the field of economics (Ak- erlof and Kranton 2000; Akerlof and Kranton 2002; Akerlof and Kranton 2005).

Recent experimental evidence has shown that social preferences are affected by group identity (Van Dijk, Sonnemans, and Van Winden 2002; Y. Chen and Li 2009; Goette, Huffman, and Meier 2006), i.e., the concern for the well-being of another individual is stronger when this person shares a common group iden- tity. In the context of organizations, Akerlof and Kranton (2005) stress the importance of employees’ identification for work motivation. In line with this reasoning, Besley and Ghatak (2005) argue that organizations benefit when em- ployees share their mission (see also Francois 2000; Glazer 2004; Delfgaauw and Dur 2007; Delfgaauw and Dur 2008). Several recent contributions provide em- pirical evidence supporting this view (Tonin and Vlassopoulos 2015; Burbano 2016; Carpenter and Gong 2016; Cassar 2019). While the mission match be- tween employer and employees specifically refers to the channel of overlapping preferences towards a higher non-monetary goal, identification can be defined in a broader context. Mission alignment, thus, can be understood as one mech- anism that may evoke identification with the employer. Based on the theory of psychological needs by Deci and Ryan (2000), Cassar and Meier (2018) apply the concept of self-determination theory to the organizational context and define

“meaning of work” along the four dimensions mission, autonomy, competence, and relatedness. They describe relatedness as a feeling of connectedness to the organization and its members, thus this dimension of meaning of work closely relates to our understanding of identification.

To capture identification in the empirical part of this chapter, we make use of the widely applied and validated survey measure of “affective commitment”. The notion of “affective commitment”, which describes the strength of the emotional attachment of an employee to the employer, has first been considered in the field of organizational psychology.5 A large body of evidence (see e.g., Meyer and Allen 1984; Tett and Meyer 1993; Rhoades, Eisenberger, and Armeli 2001) has shown that employees differ in the extent to which they feel attached to the organization and that such “affective commitment” is generally considered to be the most important dimension to predict individual turnover (intention), job performance, and absenteeism (see Meyer, Stanley, et al. 2002, for a meta- analysis).

We contribute to this literature by analyzing the relationship between identifica- tion and job satisfaction, effort provision, wage growth, job search behavior, and employee mobility6, both in a theoretical model and with field data. We provide

attachment can be viewed as a match-specific component. This means that an individual’s affective commitment is typically rather stable within an organization, but is likely to vary in a different job match at a different employer.

5In a very influential contribution, Meyer and Allen (1991) argue that an employee’s ”or- ganizational commitment”, i.e., the individual’s psychological attachment to the organization, consists of three components. Besides affective commitment, the other components are “con- tinuance commitment” as the awareness of the costs associated with leaving the organization and “normative commitment” as the feeling of obligation to continue the employment.

6Kampkötter and Sliwka (2014) show that incumbent employees with high levels of firm

empirical evidence from a representative linked employer-employee dataset that not only provides ample information on individual characteristics, attitudes, and labor market outcomes, but also detailed knowledge of specific job search be- havior and outcomes, which previous datasets typically lack. This allows us to study the nexus between commitment to an employer and the job matching pro- cess in more detail. Additionally, we present evidence for the predictive power of a self-reported survey measure of identification for actual wage trajectories and turnover outcomes, and thereby contribute to the recently emerging litera- ture which emphasizes the relevance of validated survey measures for economic behavior and decision-making (Blinder and Krueger 2013; Bender, Bloom, et al.

2018; Falk and Hermle 2018; Falk, A. Becker, et al. 2018).

2.2 The Model

Consider the following simple model to illustrate the key ideas. An employee works for two periodst= 0,1. In period 0, the employee is hired by a firm. The employee’s utility function in periodt is

U(πW t, πF t) =πW t+γπF t,

where πW t is the material well-being of the employee and πF t are the profits of the employer. Let γ be a measure of the employee’s identification with the employer or his “affective commitment” towards the employer: the higherγ, the greater the extent to which the employee internalizes the employer’s well-being.

Employee and employer learn the realization ofγ after the employee is hired in period 0. The employee is initially hired at a market wagew0=wM. In period 1, the employee and the firm negotiate the wagew1and the bargaining outcome is determined by the generalized Nash bargaining solution, where the employee has bargaining power λ. In each period, the employee chooses a work effort a which generates a profitπF t =K(at)−wt for the employer and a material well-beingπW t =wt−c(at) for the employee withKa, ca, caa>0 andKaa≤0.

2.2.1 Analysis

The employee’s utility in a period t is thus

wt−c(at) +γ(K(at)−wt) and the employee chooses an effort such that

γK0(at)−c0(at) = 0 (2.1) which implicitly defines his effort a(γ) such that

∂a(γ)

∂γ =− K0(a)

γK00(a)−c00(a) >0 and this implies the following simple first result:

tenure have lower wages compared to newly hired employees in the same position arguing that the fact that these employees did not leave the firm in the past indicated higher mobility costs (which also capture some non-monetary elements such as affective commitment to the incumbent employer), which weakens their bargaining position.

Proposition 1 When the employee exhibits a stronger identification with the employer, (i) his marginal utility from wages is lower and (ii) his work effort is higher.

Note that this corresponds to typical results in the literature on employee iden- tification (Akerlof and Kranton 2005), mission motivation (Besley and Ghatak 2005; Cassar 2019), or public sector and non-profit motivation (Delfgaauw and Dur 2007; Delfgaauw and Dur 2008): The well-being of an employee with a higher identification with the employer depends on his wage level to a lesser extent. Moreover, as he internalizes the employer’s output to a greater extent, such an employee will work harder.

2.2.2 Wage Bargaining

In a next step, we analyze the wage bargaining outcome in period 1 and the resulting change in wages between periods 0 and 1. The employee’s utility when staying with the firm is

(1−γ)w1+γK(a(γ))−c(a(γ))

and his threat point utility is equal to uM.7 The employer’s utility when the employee stays is

K(a(γ))−w1

and we normalize the employer’s threat point utility to 0.8 Note that the agent stays with the firm if there are gains from trade, i.e., a wage level exists in which both the firm and the agent are better off when the agent stays, which will be the case if

K(a(γ))−c(a(γ))≥uM.

In this case, we apply the generalized Nash bargaining solution to obtain the rate of wage growth:9

Proposition 2 When K(a(γ))−c(a(γ))> uM the employee stays with the firm and his wage increases by

∆ (γ, a) =w1

w0 =λK(a(γ)) + (1−λ)uM−(γK(a(γ))−c(a(γ))) (1−γ)

wM . (2.2)

Conditional on efforta, wage growth is downward sloping inγ, i.e.,

∂∆ (γ, a)

∂γ <0.

7If the worker does not know the level of identification realized in a different job and has some beliefs about the realization of emotional attachment at the new employer,uM is, for instance, equal toEγ[(1−γ)wM+γK(a(γ))−c(a(γ))].

8This is, for instance, the case in a competitive labor market wherewM =Eγ[K(a(γ))].

9Note that here we characterize the relative wage growth as this is what we will explore empirically in the subsequent section.

When efforts are endogenous, then

∂∆ (γ, a(γ))

∂γ = λ

wM

K0(a(γ))a0(γ)

| {z }

>0

+ (1−λ)uM −(K(a(γ))−c(a(γ))) wM(1−γ)2

| {z }

<0

.

When the employer has some bargaining power (0 < λ < 1), there is a trade- off between a “compensating wage differential” effect and a “motivation” effect.

Wage increases are downward sloping in the employee’s degree of identification with the employer if, and only if, the employee’s bargaining power is sufficiently small.

Proof:See the appendix to chapter 2.

Hence, there are two effects. On the one hand, there is a “compensating wage differential” effect: The employer can push committed employees to a lower wage as they enjoy working for the firm – and this joy will be lost when the employee leaves his incumbent employer. But, on the other hand, there is also a countervailing “motivation effect”: When efforts are endogenous, committed employees work harder and are therefore more valuable for their incumbent em- ployer, allowing them to reap part of this value in negotiations. Conditional on efforts, wage growth is thus downward sloping inγ.However, the net effect of af- fective commitment on wage growth is ambiguous when efforts are endogenous.

When the employee has a strong bargaining power, the motivation effect domi- nates and wage growth is upward sloping in affective commitment. If, however, the employee’s bargaining power is sufficiently small, the compensating wage differential effect is stronger and wage growth is downward sloping in affective commitment.

2.2.3 Job Search and External Offers

Now we consider an employee’s effort to search for a new job. Assume now that before period 1, the worker can choose a search effortpat costk(p) with kp, kpp>0. This search effort determines the likelihood of receiving an outside offer generating utilityuO that may improve his outside option. The worker’s search is successful (d= 1) with probability p. In this case, the new outside option is drawn from a probability distribution with pdff(uO) on the support ]uM,∞[. If the search is not successful (d= 0), the outside option remainsuM. When the worker receives the external offer, he thus either negotiates a higher wage or leaves the firm obtaining a utilityuO. He will again stay with the firm if there are gains from trade, i.e.,K(a(γ))−c(a(γ))> uO.The negotiated wage increase when he stays is again determined by Nash bargaining analogously to Proposition 2 and thus will be equal to

∆ (uO) =

λK(a(γ)) + (1−λ)uO−(γK(a(γ))−c(a(γ))) (1−γ)

wM

.

The outside offer will thus increase the agent’s wage by (1−λ)(1−γ)(uO−uM) and utility by (1−λ)(uO−uM) when staying. But if uO is sufficiently large, the employee leaves the firm and his utility then increases by

uO−[(1−λ)wM +λ(K(a(γ))−c(a(γ)))]. Hence, the expected utility gain from obtaining an external offer is E[∆u] =

Z K(a(γ))−c(a(γ))

uM

(1−λ) (uO−uM)f(uO)duO

+ Z ∞

K(a(γ))−c(a(γ))

(uO−(1−λ)wM −λ(K(a(γ))−c(a(γ))))f(uO)duO

which determines the worker’s optimal search effort. We can show:

Proposition 3 If the employee obtains an external offer d providing utility uO > uM, he will stay with the firm if K(a(γ))−c(a(γ))> uO. In this case the worker’s expected wage increase conditional on the offerdis

E[4|d] =

λK(a(γ)) + (1−λ)uM−(γK(a(γ))−c(a(γ))) (1−γ)

wM

(2.3) +d·(1−λ)

(1−γ)

E[uO|uO≤K(a(γ))−c(a(γ))]−uM

wM

(2.4) The stronger the employee’s identification with the firmγ, the larger is the wage growth the agent achieves when having obtained an external offer. A stronger employee identification, however, reduces the employee’s search effort and thus the likelihood that he leaves the firm.

Proof: See the appendix to chapter 2.

As we have seen before, without an external offer, wages may increase to a lesser extent for more emotionally attached workers (when either their bargaining powerλis small or when efforts are held constant). However, as the result shows, once the worker has obtained an external offer but stays with the employer, there is always a countervailing effect. To see this, note that

E[4|d= 1]−E[4|d= 0] = (1−λ) (1−γ)

E[uO|uO≤K(a(γ))−c(a(γ))]−uM

wM

is strictlyincreasinginγ. Hence, an external wage offer comes along with higher wage increases for more emotionally attached workers. The reason is twofold:

First, the firm matches higher wage offers when a worker is more emotionally at- tached as such workers are more productive, i.e.,E[uO|uO≤K(a(γ))−c(a(γ))]

is increasing inγ. But moreover, as such a worker’s utility is less sensitive to money, the firm has to raise the worker’s wage by a greater extent to match the higher threat point resulting from the external offer.10

10Note that theutility increaseobtained through an external offer does not depend onγ when the worker stays.

The question naturally arises why an employee with a higher γ exerts lower search efforts. The reason is that with positive probability, the utility provided by the external offeruOis so large that the worker leaves the firm. But for more attached workers this is less likely, as such workers have a higher productivity, i.e., K(a(γ))−c(a(γ)) is larger. Moreover, if such workers leave, their utility gain from moving is smaller as they lose the psychological benefit of the larger emotional attachment. Thus, it may be that an employee with a higher emo- tional attachment to the firm will have a lower wage growth without an external offer, but achieves a higher wage growth once having obtained an external offer.

2.2.4 Predicted Patterns

Our model takes the strength of the employees’ emotional attachment to the employer as given and derives predictions for the future employer-employee re- lationship and behavior. Note that we do not aim at identifying causal effects of employee identification with the employer, but rather use our formal model to describe qualitative characteristics of the conditional expectation function of future wage growth, work efforts, and search activities, conditional on the degree of employee identification. The following stylized expected patterns sum up our theoretical results: A stronger identification of an employee with the employer predicts

• a lower marginal utility from wages:

∂E[u(w, γ)|w, γ]

∂w∂γ <0,

• higher work effort:

∂E[a|γ]

∂γ >0,

• a lower wage growth (conditional on work effort):

∂E[4 |γ, a]

∂γ <0,

• lower search efforts and a lower likelihood of obtaining an external wage offer:

∂E[p|γ]

∂γ <0.

• a higher wage growth when having obtained an external offer

∂(E[4 |γ, d= 1]−E[4 |γ, d= 0])

∂γ >0.

We test these patterns empirically using a representative matched employer- employee panel dataset.

2.3 Data and Descriptive Statistics

The empirical analysis is based on the first three waves of the Linked Personnel Panel (LPP), an employer-employee panel dataset that has been developed by the authors jointly with the Centre for European Economic Research (ZEW) Mannheim and the Institute for Employment Research (IAB) Nuremberg on behalf of the German Federal Ministry of Labor (BMAS). The LPP is a linked employer-employee dataset that is representative for German private sector es- tablishments with more than 50 employees subject to social security contribu- tions (see Kampkötter, Mohrenweiser, et al. 2016, for details on the construction and design of the dataset).11 The employer survey is based on a subsample of the IAB Establishment Panel and is stratified according to four employment classes (50-99; 100-249; 250-499; 500 and more employees), five industries (met- alworking and electronic industries; further manufacturing industries; retail and transport; services for firms; information and communication services) and four regions of Germany (North; East; South; West). The sample comprises 1,219 es- tablishments in the first wave (2012/13), 771 in the second wave (2014/15) and 846 in the third wave (2016/17) and is representative for the above-mentioned establishment characteristics. A random sample of employees was drawn from participating establishments in each wave to take part in at home telephone interviews (CATI). The employee survey was carried out in 2012/13 (first wave) comprising 7,508 employees, in 2014/15 (second wave) comprising 7,109 em- ployees, and in 2016/17 (third wave) comprising 6,428 employees.

Besides information on the workforce structure and composition, employee rep- resentation, ownership, legal structure and establishment-level performance mea- sures originating from the IAB establishment panel, the LPP employer survey focuses on human resource management practices in firms in more detail. The employee survey includes a rich set of items on socio-demographic characteristics and detailed survey scales to assess job characteristics, personal characteristics, attitudes, and behavioral outcome variables.

Our main independent variable is affective commitment to the organization.

This is a psychological construct that is widely used in organizational psychology and management research which captures an employee’s emotional attachment to or identification with his employer. The dataset includes a six-item short scale by Meyer, Allen, and Smith (1993). This construct is a reduced but embedded scale of the original version introduced by Allen and Meyer (1990). Items were measured on a five-point Likert scale and show a high level of scale reliability with a value of Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83. The six items read as follows: “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization”,

“This organization has a great deal of personal meaning for me”, “I really feel as if this organization’s problems are my own”, “I do not feel a strong sense of ’belonging’ to my organization”, “I do not feel ’emotionally attached’ to this organization”, “I do not feel like ’part of the family’ at my organization”.12 The mean and median for this construct (unstandardized) range around 3.7 and 3.8 in both the first and the second wave.

11This study uses the Linked Personnel Panel (LPP), wave 1617, http://dx.doi.org/10.5164/IAB.LPP1617.de.en.v1

12The latter three items are reverse coded.

Further survey variables we use are job and pay satisfaction, which are mea- sured on an 11-point Likert scale adapted from the German Socio-economic Panel Study from zero to ten with a mean of 7.5 and 7.6 (median 8) and 6.7 and 6.8 (median 7) in the first and second wave, respectively. Both commitment and job satisfaction are standardized with zero mean and unit variance before entering the regressions. Furthermore, we use the number of sick days within a year and the hours of unpaid overtime per week reported by the employees as proxies for effort within our analyses. Additional individual-level control vari- ables include job status (blue collar vs. white collar), supervisory position, part time, gender, secondary and tertiary education, age, gross hourly wage, limited work contract, marital status, and household size. The set of establishment-level controls comprises industry, region, establishment size, ownership structure, and independent establishment. In table 2.6 in the appendix to this chapter, we pro- vide an overview of the descriptive statistics of all the relevant variables on the employee and establishment level we use in our regressions.

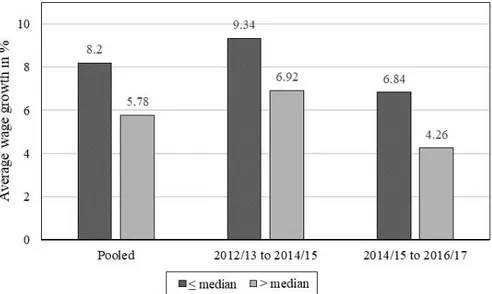

Hourly wage growthis measured as annual change in hourly wages from the first to the second wave and the second to the third wave respectively (measured in percent).13 In order to discard data outliers, we winsorize this variable at the 1% level in each tail. Average hourly wage growth equals 8.2 and 5.6%

respectively within the time span of two years, the median hourly wage growth ranges comparably lower at 6.7 and 3.9%. Active job searchis defined as dummy variable with value 1 if an employee has actively searched for a job in the 12 months prior to being surveyed. Job offer is a dummy variable coded 1 if an employee has been approached by another employer within the 12 months prior to the interview and has, as a consequence of the poaching behavior, received a specific job offer, and 0 otherwise (no job offer received and not being approached by an employer). Realized voluntary turnover is coded as 1 if the reason for the realized job change is voluntary, i.e., a termination by the employee itself and 0 if the employee is still with his incumbent employer.

2.4 Results

2.4.1 Job Satisfaction, Wages, and Affective Commitment

In order to test our first stylized prediction, we regress job satisfaction in period t+1 on hourly wage in t+1, commitment in t and the interaction of both.

The key idea of our first analysis is that we take job satisfaction as a measure of employee well-being and test the prediction that for employees with high affective commitment, the conditional expectation of their well-being is less dependent on their wages.

13Most of the predicted patterns from our theory section, which we will analyze empirically in the following, refer to changes between periodtandt+1 or outcomes int+1based on variables int. Therefore, given the structure of our data, teither refers to the first wave in 2012/13 or the second wave in 2014/15 andt+1to the second wave in 2014/15 or the third wave in 2016/17 respectively. Thus, the difference betweent andt+1 always relates to a two-year window. This also implies that the data from the third wave, in most of our analyses, will only be used to construct our dependent variables, but not as predictor variables.

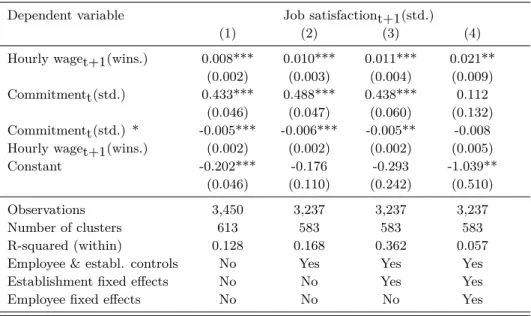

In the first specification of table 2.1, we analyze pooled cross-sectional data from all three waves without any additional controls. In the second specification, we add employee and establishment characteristics. In specification (3), we include establishment fixed effects and in specification (4) employee fixed effects. The results show that total hourly wage is positively associated with job satisfaction but that the economic magnitude is small. This result mirrors findings from previous work (see e.g., Clark and Oswald 1996), where the absolute wage level also played a minor role for the prediction of job satisfaction. In line with our first stylized prediction, the coefficient for the interaction term between affective commitment and hourly wage has a negative sign. Thus, indicating that the conditional expectation function of job satisfaction has a weaker slope with respect to wages for employees who exhibit a stronger emotional attachment towards their employer. The size of the interaction term roughly corresponds to about 40 to 60% of the size of the wage coefficient in all three specifications, i.e., for a person with an affective commitment that is about 1.5 standard deviations above the mean, wages are not predictive for job satisfaction while the predictive power of wages for satisfaction is much higher for less emotionally attached workers. The interaction term remains statistically significant when we include establishment fixed effects. When we include worker fixed effects, the point estimate still shows a positive relationship but is no longer significant.

Table 2.1: Job Satisfaction and commitment

Dependent variable Job satisfactiont+1(std.)

(1) (2) (3) (4)

Hourly waget+1(wins.) 0.008*** 0.010*** 0.011*** 0.021**

(0.002) (0.003) (0.004) (0.009)

Commitmentt(std.) 0.433*** 0.488*** 0.438*** 0.112

(0.046) (0.047) (0.060) (0.132)

Commitmentt(std.) * -0.005*** -0.006*** -0.005** -0.008

Hourly waget+1(wins.) (0.002) (0.002) (0.002) (0.005)

Constant -0.202*** -0.176 -0.293 -1.039**

(0.046) (0.110) (0.242) (0.510)

Observations 3,450 3,237 3,237 3,237

Number of clusters 613 583 583 583

R-squared (within) 0.128 0.168 0.362 0.057

Employee & establ. controls No Yes Yes Yes

Establishment fixed effects No No Yes Yes

Employee fixed effects No No No Yes

Notes: Robust standard errors clustered on establishments in parentheses. Control variables on employee level include: blue collar, supervisory position, part time, female, secondary and tertiary education, age, limited work contract, marital status, household size, and year dummies. Control variables on establishment level include: industry, region, establishment size, ownership structure, and independent establishment. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

2.4.2 A Proxy for Work Effort

The second stylized prediction refers to the relationship between affective com- mitment and work effort in the same year. Since work effort is hard to measure across a broad number of firms, we use the number of sick days within a year and the amount of unpaid overtime hours per week, which essentially constitutes a gift to the employer, as two alternative proxies for work effort (see e.g., Engel- landt and Ribhahn 2011). In table 2.2, we first analyze the pooled cross-section and then gradually include employee and establishment controls as well as estab- lishment and employee fixed effects. Again, all specifications show the expected sign, i.e., more committed employees take fewer sick days (specifications (1) to (4)) and work, on average, more overtime (specifications (5) to (8)). We find that employees with a one standard deviation higher affective commitment are, on average, two days less absent. This result is robust to the inclusion of estab- lishment fixed effects, however, it becomes smaller and statistically insignificant when we apply employee fixed effects.14 With respect to unpaid overtime, the analyses show that employees with a higher commitment of one standard de- viation work between 0.07 and 0.2 hours per week more overtime compared to their counterparts with lower affective commitment. For both effort proxies, the coefficients correspond to about a 10% higher effort provision for a one standard deviation higher affective commitment compared to the respective mean values (see table 2.6 in the appendix to this chapter).

14This may be due to the fact that affective commitment is rather stable over time such that there is little within person variation: The Pearson correlation coefficient is 0.65 (p<0.0001) for affective commitment intandt+1and 0.60 (p<0.0001) for affective commitment intand t+2. Moreover, measurement error may lead to attenuation bias.

Table2.2:Sickdaysandunpaidovertime DependentvariableSickdaystUnpaidovertimet (1)(2)(3)(4)(5)(6)(7)(8) Commitmen

t t

(std.)-2.011***-1.897***-1.793***-0.9980.192***0.065**0.105***0.014 (0.234)(0.252)(0.267)(0.697)(0.031)(0.029)(0.031)(0.041) Constant11.974***18.257***18.364***7.0880.618***-0.381*-0.961**0.657 (0.342)(1.496)(4.449)(5.000)(0.045)(0.198)(0.442)(0.535) Observations14,93014,34014,34014,34014,89814,30214,30214,302 Numberofclusters1,1661,1501,1501,1501,1661,1491,1491,149 R-squared0.0070.0460.1430.0160.0050.0820.2070.010 Employee&establ.controlsNoYesYesYesNoYesYesYes EstablishmentfixedeffectsNoNoYesYesNoNoYesYes EmployeefixedeffectsNoNoNoYesNoNoNoYes Notes:Robuststandarderrorsclusteredonestablishmentlevelinparentheses.Controlvariablesonemployeelevelinclude:bluecollar,supervisory position,parttime,female,secondaryandtertiaryeducation,age,limitedworkcontract,maritalstatus,householdsize,andyeardummies. Controlvariablesonestablishmentlevelinclude:industry,region,establishmentsize,ownershipstructure,andindependentestablishment. ***p<0.01,**p<0.05,*p<0.1.

2.4.3 Predicting Wage Growth

In the following section, we study the extent to which affective commitment as measured in period t predicts actual wage growth between t and t+1. Again, note that t either refers to the first wave in 2012/13 or the second wave in 2014/15 andt+1 to the second wave in 2014/15 or the third wave in 2016/17 respectively. Hence, wage growth is always calculated over a period of two years.

Recall that without information on the employee’s bargaining power, our model makes no prediction on the sign of the slope of the conditional expectation func- tion of wage growth betweentandt+1 as a function of affective commitmentγ as measured int. However, it predicts that the slope should be negative when we condition on work efforta

∂E[∆|γ, a]

∂γ <0.

As a first step, we descriptively explore the connection between affective com- mitment in periodtand wage growth betweent andt+1. Figure 2.1 shows mean wage growth when using a median split of all workers in the sample by their level of affective commitment, both pooled across all waves as well as separately for wage growth from 2012/13 to 2014/15 and 2014/15 to 2016/17. The figure already indicates a sizeable compensating wage differential effect: Employees with above median levels of affective commitment exhibit a substantially lower wage growth.

Figure 2.1: Wage growth for employees by degree of affective commitment