Research Collection

Master Thesis

Integrating key competencies in sustainability, emergency

management and resilience into a capacity building program for local governments

Author(s):

Bhagavathula, Susila Publication Date:

2020

Permanent Link:

https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000459356

Rights / License:

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International

This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use.

ETH Library

Master's thesis

Integrating key competencies in

sustainability, emergency management and resilience into a capacity building

program for local governments

By Susila Bhagavathula (17-937-889)

Master's degree programme in Environmental Sciences Major in Environmental Systems and Policy

Supervisor:

Prof. Dr Michael Stauffacher, Department of Environmental Systems Science, ETH Zürich

Co-Supervisor: Dr. Katja Brundiers, School of Sustainability, Arizona State

University

March 8

th, 2020

Edited: December 20

th, 2020

Table of Contents

Table of tables ... 4

Table of figures ... 4

1. Introduction ... 5

1.1. State of research and practice ... 7

1.2. Knowledge Gap ... 8

1.3. Case study ... 9

1.4. Research questions... 9

2. Methods ... 10

2.1. Research and data collection approach ... 10

2.2. Data analysis ... 16

3. Results ... 17

3.1. Which of the competencies in the existing frameworks in sustainability, emergency management and resilience are entailed in select capacity building trainings for local governments and how do the frameworks relate to each other? ... 17

3.1.1. Overview of Key Competencies in Sustainability found in the design of each training ... 17

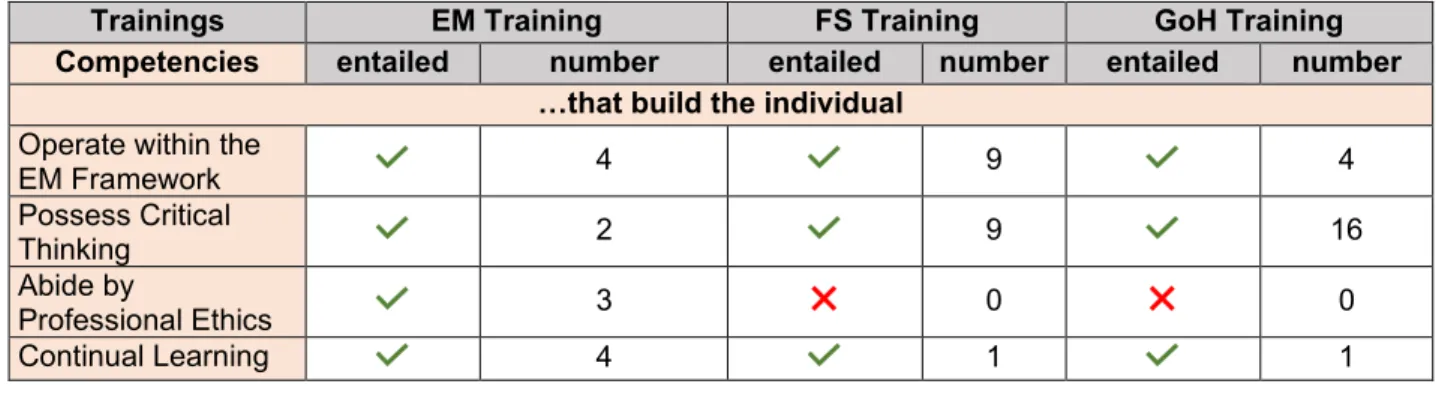

3.1.2. Overview of Next Generation Core Competencies found in the design of each of the selected trainings ... 22

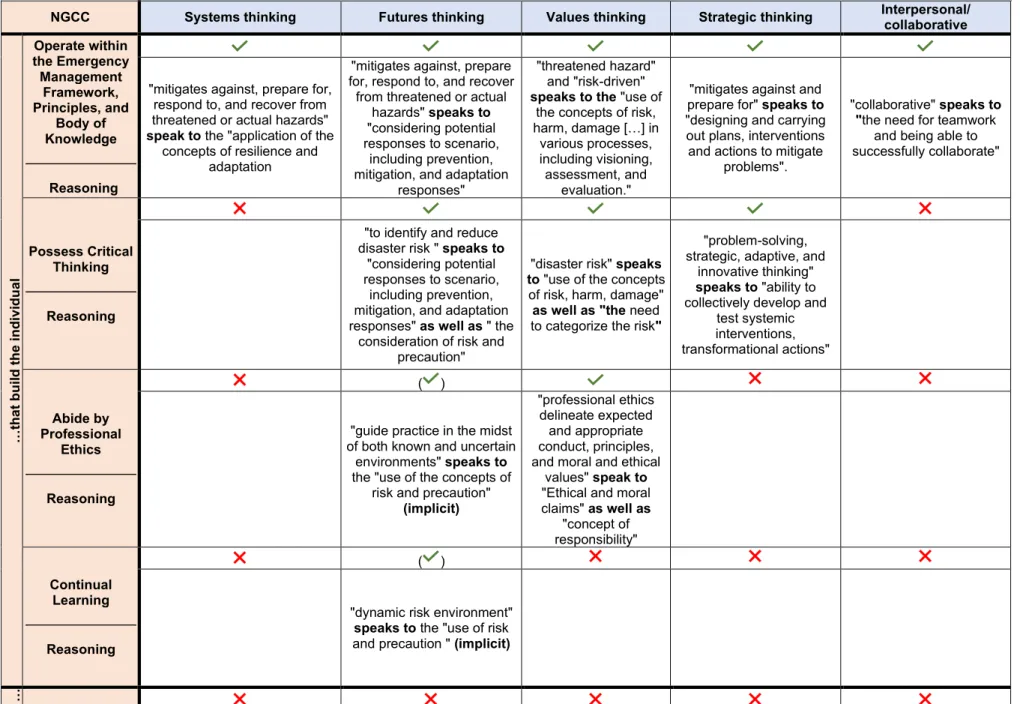

3.1.3. Comparison of frameworks of the Next Generation Core Competencies in Emergency Management and Key Competencies in Sustainability ... 25

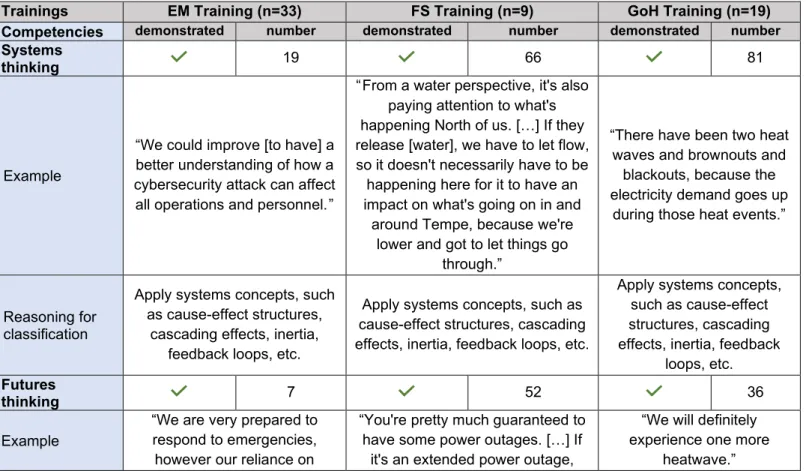

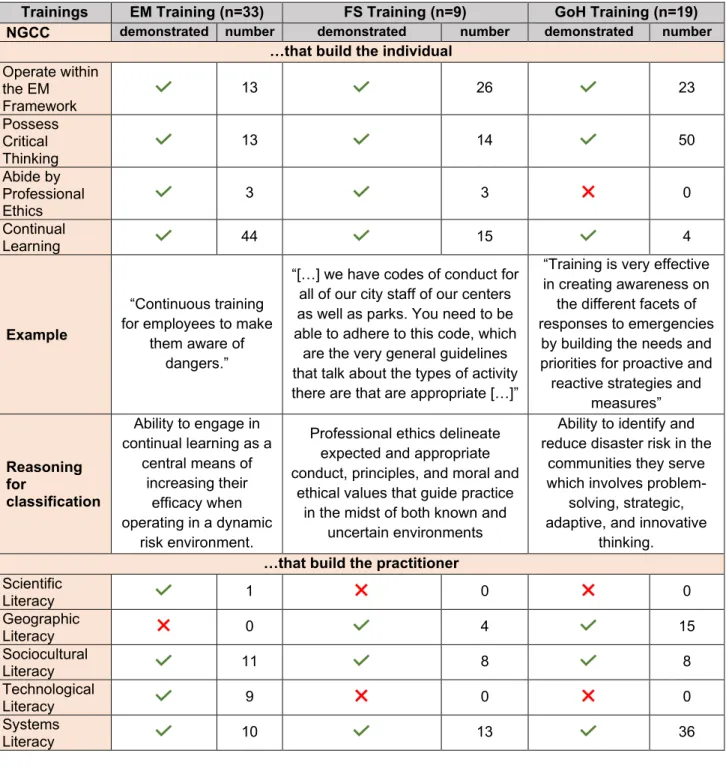

3.2. Which competencies are already demonstrated through the city governments’ processes and which ought to be further implemented through the above-mentioned capacity building programs? ... 32

3.2.1. Which competencies are already demonstrated through the city

governments’ processes? ... 323.2.2. Which competencies ought to be further implemented through the above- mentioned capacity building programs? ... 33

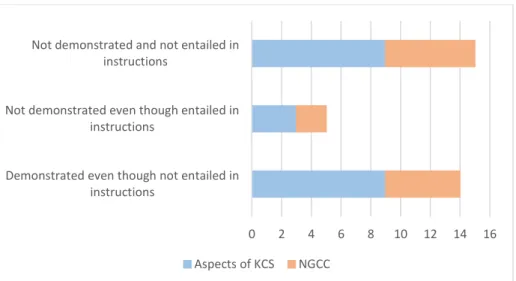

3.2.3. Comparison of trainings ... 39

3.3. How can the three sets of competencies be integrated into a proposal for one capacity building program to support achieving the interrelated sustainability, emergency management and resilience objectives of local governments? ... 42

3.4. What adjustments, if any, would strengthen the learning experience of the capacity building programs to foster a collaborative approach with long- term impacts on the institutional work of city governments? ... 44

3.4.1. Recommendations on training design, logistics and set-up ... 44

3.4.2. Recommendations on further trainings and future training participants ... 45

4. Discussion ... 46

4.1. Discussion around comparison of KCS and NGCC that show differences and similarities ... 46

4.2. Discussion of suggestions made for future training design on the basis of competencies entailed in the design versus demonstrated by participants ... 47

4.2.1. Competencies referenced in design vs. as demonstrated during trainings individually allude to assumptions for future training designs ... 47

4.2.2. Each training expressed competencies to a different extent which alludes to assumptions for future training designs ... 48

4.2.3. Participants indicate relevance of values-thinking competency for their work 49 4.2.4. Discussing trainings on the basis of content knowledge: Recovery phase needs to be entailed more ... 50

4.3. Discussion on how best to integrate the competency sets and integration of the notion of institutional work ... 50

4.3.1. Discussion on how best to integrate the sets of competencies ... 50

4.3.2. Suggestions on how to strengthen the learning experience of the training program ... 51

4.4. Methodical limitations ... 52

4.5. Next steps ... 53

5. Conclusion ... 53

6. Acknowledgements ... 53

7. References ... 54

Table of tables

Table 1: Assumptions made about what content knowledge ought to be conveyed during

selected trainings. ... 13 Table 2: Information on training set-ups and data collected ... 15 Table 3: Data collection and analysis methods to answer research questions ... 16 Table 4: Key competencies in sustainability (by Wiek et al. (2011)) found in the design of each of the selected trainings... 18 Table 5: Next Generation Core Competencies in Emergency Management (by Feldmann-Jensen et al. (2017)) found in the design of each of the trainings ... 22 Table 6: Comparison of NGCC and KCS with explanations derived from the definitions and aspects of both competency sets on how the comparison was made. ... 28 Table 7: Key competencies in sustainability fostered in selected trainings during the

training/game play and as self-assessed in open-ended questions in the surveys ... 33 Table 8: Next Generation Core Competencies in Emergency Management fostered in selected trainings during the training/game play and in open-ended questions in the surveys ... 37 Table 9: KCS entailed as per design aspiration in each training compared to demonstrated by participants in all three trainings combined as one capacity building program ... 42 Table 10: NGCC entailed as per design aspiration in each training compared to demonstrated by participants in all three trainings combined as one capacity building program ... 42

Table of figures

Figure 1: Assumption of KCS and NGCC structure, including elements, their relationships and terminology used for this research project. ... 12 Figure 2: Correlation of times (aspects of) competencies were entailed/ not entailed in training instructions vs. demonstrated/ not demonstrated ... 40 Figure 3: Aspects of KCS entailed as per design aspiration in each training compared to

demonstrated by participants. ... 40 Figure 4: NGCC entailed as per design aspiration in each training compared to demonstrated by participants ... 41 Figure 5: Number of times participants spoke to the 4 phases of emergency management ... 43 Figure 6: Distribution of participants’ occupations per training (shown in order of trainings held) ... 44

Abstract Cities are highly affected by changing environmental and social conditions, such as climate change and impending disasters. The three areas of urban sustainability, emergency management and urban resilience are the areas primarily focused on addressing these challenges on a city level. One way to promote an integrative city-level approach across the three fields (sustainability, emergency management and resilience) is through capacity building programs. So far, only few capacity-building programs attempted to implement an integrated set of two or more competencies and to foster collaboration amongst at least two of the three different fields. To address this gap, the research was conducted in the City of Tempe in Arizona, USA by means of a literature research on integrating the competencies’ frameworks, a case study including the hosting of three capacity building trainings including two or more competency sets and the assessment of the trainings through qualitative analysis. The overarching question of how the three sets of competencies can be integrated into a proposal for one capacity building program to support achieving the interrelated sustainability, emergency management and resilience objectives of local governments was assessed. The results show that firstly, no resilience competency framework was found in the literature, thus resilience competencies were not assessed in the training. Secondly, the comparison of sustainability and emergency management competency frameworks suggests that the sustainability competencies (KCS) and emergency management competencies (NGCC) have overlaps as well as distinct differences. Thirdly, all KCS and all of the NGCC were entailed in at least one of the training instructions and fourthly were addressed by participants in at least one of the three trainings. In addition, participants self- reported that all KCS were already part of the city governments’ processes to varying degrees.

Lastly, participants’ satisfaction with the trainings individually and combined as training program were high. However, recommendations for improvements of the capacity building program were made and the need for more trainings was expressed, especially trainings including community members and other city partners and stakeholders. Future research ought to explore the relationship between the KCS and NGCC (i.e. NGCC’s behavioral anchors and key actions and the aspects of KCS) more and a resilience competency framework ought to be explored.

Introduction

Cities are highly affected by changing environmental and social conditions, such as climate change, air pollution, resource scarcity, rapid urbanization and increasing inequity (OECD, 2015;

UN Habitat, 2016; United Nations, 2018). As federal action on i.e. climate change is lagging in the United States, cities are increasingly responding to them, especially since most of the world’s population nowadays lives in cities and is thus primarily affected (Keeler et al., 2017; United Nations, 2018).

The three areas of urban sustainability, emergency management and urban resilience are the areas primarily focused on addressing these challenges on the city level. Urban sustainability deals with “governance and integrated planning, fiscal sustainability, economic competitiveness, environment and resource efficiency, low carbon emissions and resilience, and social inclusiveness” (Global Platform for Sustainable Cities & World Bank, 2018, p.11). Emergency management deals with impending disasters and creating a culture of preparedness within the city government and the population, reducing the complexity of response processes along all four phases of emergency management (mitigation, preparedness, response, recovery) and working on successful recovery post-disaster (Lindsay, 2012). Urban resilience deals with maintaining or rapidly returning to desired functions when coping with stressors (such as rapid urbanization and an increasing gap between the rich and the poor) and shocks, such as heat waves, earthquakes and floods, though conflicting definition have been identified (Meerow et al., 2016).

Creating synergies among sustainability, emergency management and resilience efforts within city structures are becoming more prominent, as only the integration of all three fields cover the range of diverse and multi-fold challenges a city of the future must face (Anderies et al., 2013;

Schipper et al., 2016; Tveiten et al., 2012). For example, urban sustainability strategies concerned with e.g. creating more renewable energy resources to reduce carbon emissions to combat climate change in equitable ways, would also account for an emergency management lens, anticipating hazards such as how to ensure sufficient energy supply through renewables in case of a crisis event, i.e. floods and preparing hazard mitigation and response strategies.

However, creating these synergies is challenging, as it is apparent that institutions and structures are not yet set up to address this potential for synergies adequately. Structurally, city governments often deal with sustainability, emergency management and resilience in a distinct and separate manner (Gargan, 1981). Emergency management is either incorporated into police and fire departments or operates as a stand-along department within a city (FEMA, 2014). For resilience work, cities have no coherent organizational approach yet; resilience officers work from within sustainability offices to safety and emergency management offices or the energy and water departments, with some cities employing resilience officers (Miller et al., 2019). Similar to resilience work, sustainability is either embedded within several city departments ranging from public works, environmental services, planning or community development to the city manager’s office; or operates as an independent office or department of sustainability (Krause et al., 2016).

As sustainability alone is of cross-cutting nature, solutions are often known but not implemented efficiently, effectively or fast enough.

This is due to the fact that they lack involving different departments or institutions, since the three areas of practices in sustainability, emergency management and resilience often still work in silos as historically defined (Gargan, 1981). This fragmentation of solutions to complex problems within a city government makes it more difficult to coordinate, hindering their effectiveness and long-term success. In addition, the complexity of challenges and solutions requires city staff and leadership

to build new capacities that enable them to take effective and transformative action (Global Consortium for Sustainability Outcomes, 2017). Furthermore, calls have been made to create synergies in education in regards to future professionals. Schneider (2013) makes the claim for emergency management professionals to be more extensively trained in sustainability, as

“sustainability is the principle around which emergency management must be organized” (p.60), as it provides the value to a desirable outcome, the ethical responsibility when considering inter- generational perspectives and considering future-oriented activities and more.

One way to promote a synergistic and integrative approach across the three fields (sustainability, emergency management and resilience) and address the challenges on a municipal level is through capacity-building programs. Capacity building is a tool to “improve the performance of local organizations by addressing human resource, material or logistical, institutional and other constraints” (as stated on the webpage of the report by the United Nations Capital Development Fund, 2006). One way to improve performance and address the constraint of lacking capacity is through the promotion of competencies in capacity building programs. Competencies have been identified as a critical reference point for developing “knowledge, skills, and attitudes that enable successful task performance and problem solving” (Wiek et al., 2011, p.204).

However, there is more to capacity building programs than just the integration of competencies.

Whilst competencies and capacity building are a way to promote and convey individual competencies, it is important to connect these to the larger work contexts, so that capacity building programs support the building of human and institutional capacity and are not just a one-off activity. The concept of “institutional work” is used to explain how capacity building programs need to be designed to facilitate the connections of new capacities with institutional structures (e.g., the formal and informal rules and procedures). Institutional work is defined as “a purposive action of organizations and individuals aimed at creating, maintaining, and disrupting institutions”

(Lawrence & Suddaby, 2006, p. 215). This is also supported by recent publications of e.g. Barin Cruz et al. (2016) who speak to how institutional work contributes to institutional resilience. As in the current structures highlighted above, institutional work in the three fields happens in separate and distinct departments within a city government, a different approach must be promoted to create more inter-departmental coordination. Thus, institutional work through local government capacity building is a way to redefine the relationship between all three fields beyond the understanding of Lawrence & Suddaby (2006), in addition to promoting the integration and the combined approach of cities’ sustainability, disaster preparedness in emergency management as well as resilience work.

1.1. State of research and practice

Capacity building is nowadays often referenced in the context of local capacity building for communities, especially in emergency management, which entails educating the public as well as supporting community-led development (Cavaye, 1999; Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment, 2016). Local government capacity has formerly been defined as “policy, resource and program management” (p.650) with separation of the functions providing conceptual clarity for better governance structures (Gargan, 1981). The term capacity in the current context refers to

“the overall ability of the individual or group to […] perform the[ir] responsibilities [within the local government]” (Franks, 1999, p. 52). As time progressed, new capacities had to be incorporated by local governments and only recently have new capacities been integrated into local government capacity building trainings (c.f. FEMA, 2012; Keeler et al., 2017; Withycombe Keeler et al., 2018).

These capacity building trainings include, for instance, for sustainability the so called serious games such as “AudaCITY” (Withycombe Keeler et al., 2018) or for emergency management FEMA’s table-top training “The Whole Community: Planning for the Unthinkable” (FEMA, 2012).

The concept of resilience is promoted as an integrated set linked with sustainability competencies in the game “Future shocks and city resilience” (Keeler et al., 2017).

Serious games seem especially suitable to build capacity, because they simulate decision making within a city in a playful manner, evoking interest in the newly introduced capacity and enhancing the process of remembering information whilst giving participants a holistic view of an issue or challenge (Keeler et al., 2017; Solinska-Nowak et al., 2018). Solinska-Nowak et al. (2018) reviewed serious games for disaster risk management available as capacity building trainings and identified that these trainings are a good way to raise awareness of disaster risks by reaching diverse audiences, assist to identify hazards and take preventive actions, while simulating disasters in a realistic way by triggering empathy. In contrast, Edwards et al. (2019) reviewed literature on serious games, in particular role-playing games for natural resource management and highlight that while serious games are found to be a valuable tool for adaptive governance approaches, they found a lack of games being able to overcome the community and higher-level decision-making gap that often are faced in environmental problem solving.

So far, only few capacity building programs attempted to implement an integrated set of two or more competency sets and to foster collaboration amongst at least two of the three different fields, such as in Keeler et al. (2017). Competency-based trainings and education have received increased attention as seen in the promotion of competencies in recent literature. Sustainability competencies, so called Key Competencies in Sustainability, have been developed in higher education to define the competencies of graduates from sustainability science programs. The goal is to develop sustainability change agents, able to implement transformative actions within any setting (Wiek et al., 2011, 2016). Competencies in emergency management, the so called Next Generation Core Competencies in Emergency Management, have been developed through FEMA’s Higher Education Program and summarized in a research report on “The Next Generation Core Competencies for Emergency Management Professionals: Handbook of Behavioral Anchors and Key Actions for Measurement” (Feldmann-Jensen et al., 2017) and have recently been included in a peer-reviewed article (Feldmann-Jensen et al., 2019). Competencies for resilience have so far been identified only through the concept itself, its relationship to future uncertainties and through terms such as the ability to “bounce back” (Meerow et al., 2016).

The notion of integration of at least two of the three fields has fairly recently surfaced within published literature. Redman (2014) and Fiksel (2006) provide conceptual analysis of the relationships between sustainability and resilience. Fiksel (2006) encourages a “coordinated global effort, with participation from public, private, and nongovernmental organizations” (p.20) to create systemic and institutional changes, which he calls the adaptive systems approach to sustainability. Redman (2014) argues that sustainability and resilience are distinct yet complementary approaches that should be pursuit jointly. Drawing on these conceptual recommendations, preliminary proposals for the linking of sustainability key competencies with core competencies in emergency management to develop curricula in higher education master programs have been made (c.f. Brundiers 2018).

1.2. Knowledge Gap

While key competencies in sustainability higher education are well established within the scientific community and the various frameworks on emergency management have just recently been

synthesized by Feldmann-Jensen et al. (2017, 2019), a resilience competencies framework is just starting to be explored. For instance, when talking about urban resilience conflicting definitions have been identified (Meerow et al., 2016). Further, when speaking about the integration of key competencies in sustainability, emergency management and resilience, there seems to be a gap in literature. In addition, a gap in the literature shows that there is no comprehensive guide to how capacity building is supported and developed for local governments, especially in the context of integrating local governments’ work in the fields of sustainability, emergency management and resilience.

The objective of this research is to understand how key competencies in sustainability, emergency management and resilience can be integrated into a capacity building program for local governments.

1.3. Case study

To address this gap, the research was be conducted in the City of Tempe in Arizona, USA in collaboration with the City of Tempe’s Sustainability Director. The work tied into an ongoing process by the city on developing a collaborative approach for the city’s efforts of coordinating its work on sustainability, emergency management and resilience.

In 2016, the City of Tempe hired a full-time Sustainability Director to push sustainability in its strategic management plan and help city departments reach their sustainability targets. In November 2016, the city was selected as a pilot city to participate in a resilience workshop implementing a capacity building program in the form of a game called “Future Shocks and City Resilience” (Keeler et al., 2017). The game aims to integrate sustainability and resilience thinking when planning long-term strategies. It was played by about 50 people including senior management and top city officials and facilitated by scholars from Arizona State University, also allowing inter- and intra-departmental collaboration on sustainability efforts amongst city officials and researchers (The Global KAITEKI Center, ASU Global Sustainability, 2016). In August 2017, the city participated in a second workshop called “AudaCITY” in which participants were taught what sustainability strategies can be taken to see what impact sustainability can have on the urban environment and on people’s lives. This was followed by a third workshop including city and non- city actors to assist them in developing sustainability solutions across contexts. The three capacity building trainings served as the internal educational foundation for the City of Tempe’s first Climate Action Plan (Withycombe Keeler et al., 2018).

In 2019, the city decided to hire a full-time emergency manager, replacing the former rotational model where the city’s fire and police departments alternatingly shared the leadership on emergency management. As the function rotates, it brings the downside of doubling-up efforts on the side of the fire and police departments and the fact that there is no constant development of long-term relationships with other city departments as well as with community members and businesses. This however is crucial within an emergency management context. Implementing the new model, the city explored where the starting emergency manager will be integrated into the city staff structure (Gilbertson et al., 2019). This research tied into this study’s process of developing an integrated and collaborative approach for the city government’s sustainability, emergency management and resilience work.

1.4. Research questions

To address the objective of integrating sustainability, emergency management and resilience competencies into a capacity building program for city governments that aids them to create a and

collaborative approach for the city’s work in all three fields, this thesis will research the following questions in collaboration with the City of Tempe, Arizona, USA:

1. Which of the competencies in the existing frameworks in sustainability, emergency management and resilience are entailed in select capacity building trainings for local governments and how do the frameworks relate to each other?

2. How can the three sets of competencies be integrated into a proposal for one capacity building program to support achieving the interrelated sustainability, emergency management and resilience objectives of local governments?

3. (1) Which competencies are already demonstrated (or expressed) through the city governments’ processes and (2) and which ought to be further implemented through the above-mentioned capacity building programs?

4. What adjustments, if any, would strengthen the learning experience of the capacity building programs to foster a collaborative approach with long-term impacts on the institutional work of city governments?

1. Methods

2.1. Research and data collection approach

This research project had a transdisciplinary approach, as I worked very closely with City of Tempe staff, in particular the Sustainability Director of Tempe. Because this research project was co- developed, decisions on participants, timings of trainings and particular wordings in training materials were adjusted to the professional setting.

The following steps were taken to address the first research question (regarding determining which competencies are entailed in the selected trainings how the frameworks relate to each other):

a) Literature review: Existing frameworks in sustainability, emergency management and resilience literature were compiled, and competencies entailed in each framework were compared. The process to achieve this goal entailed appraising existing frameworks in the literature in addition to appraising literature that integrates competencies across the three fields. In order to assess further literature on competencies and their integration, literature was selected primarily from Web of Knowledge and Google Scholar based on following key words and word combinations in the search: “competencies”, “sustainability”, “resilience”,

“emergency management”, “higher education”.

For sustainability following literature was selected: Wiek et al. (2011) and Wiek et al. (2016) and for emergency management: Feldmann-Jensen et al. (2017) and Feldmann-Jensen, Jensen, Smith, & Vigneaux (2019). These were selected, as Wiek et al. (2011) are the most cited publications in the scientific literature (646 citations, Sustainability Science, as of Feb/2020) and the broader sustainability community (1232 citations, Google Scholar, as of Feb/2020). The framework provided by Feldmann-Jensen et al. (2019) was selected due to the fact that this set of competencies was derived through a FEMA Focus Group, followed by a multi-cycle Delphi study with emergency management educators, which culminated in a consultation with the wider disaster risk management community, which shows the level to which this framework is embedded within the larger emergency management community.

For resilience competencies, there seems to be no stand-alone set of competencies or framework available. This can be attributed to the fact that the definition of resilience is still

charged with tensions as identified by Meerow et al. (2016) who proposed a new definition addressing these tensions in the research literature. The notion of resilience and related competencies seem to be integrated into emergency management frameworks (i.e. Jenna Tyler & Abdul-Akeem Sadiq, 2019) and literature used to assess the integration of key competencies across mainly the fields of sustainability and emergency management are e.g. Brundiers (2018) and Keeler et al. (2017). Due to this finding, the research and the following results were focused on sustainability and emergency management competencies.

b) Analysis and comparison of competency sets: For the comparison of the Next Generation Core Competencies in Emergency Management (NGCC) and the Key Competencies in Sustainability (KCS), the peer-reviewed articles, Wiek et al. (2011) and Feldmann-Jensen et al. (2019) respectively were primarily used. Both publications introduce the respective competency frameworks and the definitions of the competencies. While Wiek et al. (2011) included information on the aspects of competencies, with an aspect of a key competency being a concept, task or method that describes a competency, information on behavioral anchors and key actions of the NGCC were not detailed in their peer-reviewed article of 2019. Therefore, the focus in this analysis was on the KCS and their aspects and on the NGCC and their three overarching, nested categories. Wiek et al. (2016) and Feldmann- Jensen et al. (2017) both focus on the operationalization of the competencies thereby detailing the aspects and behavioral anchors and key actions.

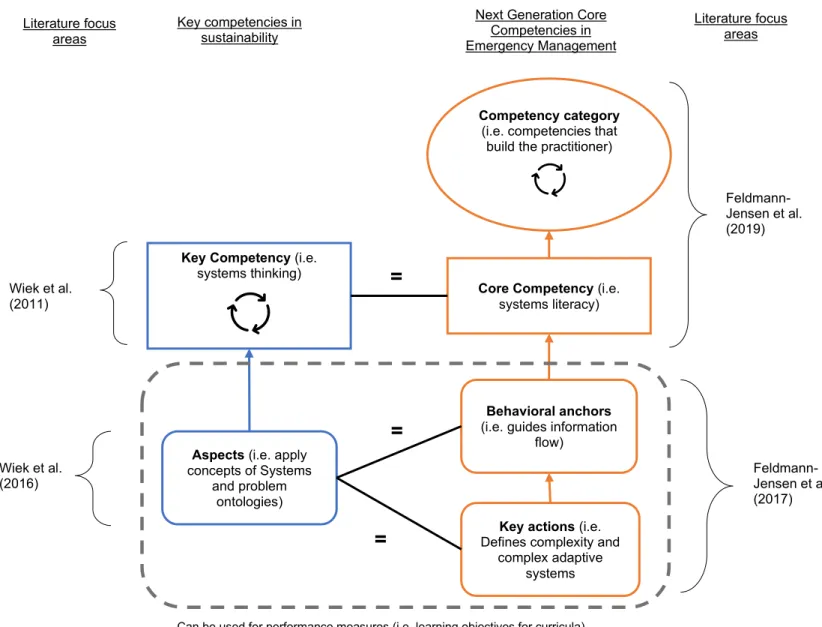

Figure 1 below shows the terminology used throughout the analysis as well as the assumptions made on how the different elements relate to each other and which literature addressed which level of elements as its focus area. The different terminologies help to differentiate which framework is being referred to: the term key competencies is used when referring to sustainability competencies, while core competencies is used to reference emergency management competencies. The framework of the KCS entails firstly, the 5 interlinked ( ) key competencies with basic academic competencies (i.e. ability to do literature review) and professional skills (i.e. project management) as their premise and secondly the aspects of which competencies are made up by. The aspects are divided into novice, intermediate and advanced levels for sustainability education (see Wiek et al., 2016).

The NGCC are made up by the three competency categories, which are nested ( ), the 13 core competencies which are distributed into the three categories and their respective behavioral anchors which entail multiple key actions, which are divided into undergraduate, master/executive and doctoral level, similarly done as with the KCS (see Feldmann-Jensen et al., 2019).

Aspects of KCS and behavioral anchors as well as key actions for the NGCC can be used for the development of performance measurements such as learning objectives and are thus seen as comparable within each framework. The same can be said for the level of competencies in each framework, which is symbolized by =.

The match on whether two competencies have similarities or not was made by:

1. presenting aspects or phrases of the definitions from NGCC that “speak to”

aspects or phrases of the definitions from the KCS,

2. several phrases were accounted for through combining them with “and”,

3. sustainability identifiers that were specified in the KCS definitions and aspects were taken out, as they were not explicit in the NGCC.

c) Selection of capacity building trainings for local governments in sustainability, emergency management and resilience: Three trainings were selected in collaboration with the city partner, of which two were serious games and one a traditional-style emergency management exercise, using the following selection criteria: (1) they were developed specifically for local governments, (2) each training specifically pertains to one or two areas of competencies (emergency management, sustainability or resilience), (3) they have been implemented with Tempe city staff before, (4) they are of interest for the city considering climate conditions and cultural contexts, (5) they are a multi-player game, in the cases of serious games, and (6) they can be integrated into already existing training efforts, as it was the case for the emergency management training. Trainings selected were:

• Emergency Management Training (EM training) held by the City of Tempe Fire and Medical Rescue Department, based on FEMA’s Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program (HSEEP) table-top exercises and Emergency Operation Center (EOC) drills with the topic of municipal cybersecurity.

Figure 1: Assumption of KCS and NGCC structure, including elements, their relationships and terminology used for this research project.

Literature focus areas

Key Competency (i.e.

systems thinking)

Aspects (i.e. apply concepts of Systems

and problem ontologies) Key competencies in

sustainability

Core Competency (i.e.

systems literacy)

Behavioral anchors (i.e. guides information

flow) Next Generation Core

Competencies in Emergency Management

Key actions (i.e.

Defines complexity and complex adaptive

systems Competency category

(i.e. competencies that build the practitioner)

Feldmann- Jensen et al.

(2019)

=

Feldmann- Jensen et al.

(2017)

=

Literature focus areas

Wiek et al.

(2011)

Can be used for performance measures (i.e. learning objectives for curricula) Wiek et al.

(2016)

=

• Sustainability and Resilience Training: "Future Shocks and City Resilience"

(FS training), which helps players assess change within a city government in regard to sustainability initiatives, leveraging of city assets and connections especially in the realm of climate change and future disasters (Keeler et al., 2017).

• Resilience Training: “Seattle Extreme Heat Scenario-Based Pilot-Project in Frontline Communities - Racial Equity Evaluation”, also called “Game of Heat”

(GoH training) which trains municipal staff to better understand heat as a hazard, better support communities, especially low-income communities and communities of color, during extreme heat events and to understand the budgeting implication of heat mitigation efforts (USDN Innovation Fund, 2016).

d) Assessment of capacity building trainings: For the appraisal to which extent the competencies identified in existing literature (see step 1a) are entailed in each capacity building training per design, the serious game materials for the FS- and GoH trainings, in particular the facilitator guides were assessed. For the EM training, the training guide provided by the organizer was analyzed. The training design refers to the descriptions of the training and to their instructions and training materials created for the particular training (e.g. facilitator guidebooks, game cards, etc.).

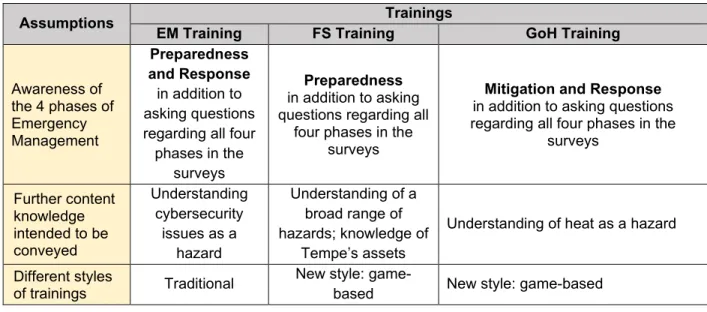

To address the second research question (regarding the creation of a proposal for one integrated comprehensive training program1), the capacity building trainings were combined in such ways to develop an integrated set of competencies in sustainability, emergency management and resilience. In addition, assumptions were made on what the three trainings are able to convey in regard to content knowledge. As presented in Table 1 below, assumptions were made that the trainings are able to:

1. Raise awareness of the 4 phases of emergency management, each focusing on one or two phases,

2. Convey further content knowledge,

3. Show benefits of traditional and new styles of trainings (such as serious games).

Table 1: Assumptions made about what content knowledge ought to be conveyed during selected trainings.

Assumptions Trainings

EM Training FS Training GoH Training

Awareness of the 4 phases of Emergency Management

Preparedness and Response

in addition to asking questions regarding all four phases in the

surveys

Preparedness in addition to asking questions regarding all

four phases in the surveys

Mitigation and Response in addition to asking questions regarding all four phases in the

surveys

Further content knowledge intended to be conveyed

Understanding cybersecurity

issues as a hazard

Understanding of a broad range of hazards; knowledge of

Tempe’s assets

Understanding of heat as a hazard

Different styles

of trainings Traditional New style: game-

based New style: game-based

1 training program or capacity building program are used interchangeably to describe multiple trainings being combined in a consecutive order

In addition, the trainings were aimed at:

4. Breaking down silos within the city government, by awareness raising and improving inter-departmental communication/collaboration which was done by inviting a wide range of participants to attend the trainings.

5. Including all levels in the city government and raising awareness on sustainability and emergency management issues and each department’s involvement and role, regardless of the department and position to create a more resilient city.

6. Improving the learning experience by sharing additional information via email prior to the last training (Game of Heat) with key information on heat as a hazard in Arizona, following best practices which recommends building additional learning elements into a training program, besides the actual training (Solinska-Nowak et al., 2018). In addition, each training was set up with a joint discussion round (semi-structured post-training discussion) at the end.

To answer the third research question (regarding determining which competencies are already demonstrated within the city government’s processes and which ought to be further implemented), four steps were taken:

a) Short pre-training questionnaire: participants shared their perception on which competencies are important to their roles and which competencies are already demonstrated in their respective departments’ processes and daily work as well as their assessments of the content matter of the trainings (e.g. their perception of hazards and their department’s involvement) in a self-assessment with 15-20 multiple choice and open-ended questions. The questionnaire was specifically designed with sustainability competencies in mind. For emergency management the focus was on the content knowledge of the four phases of emergency management in addition to the training experience and areas of improvement. The survey structure was mostly repetitive for each training, with adjustments to the context. In addition, some questions were training-specific, while certain questions were solely for the city partners’ assessments.

b) Implementation of the trainings: The trainings mentioned in 1 d) above were implemented with city staff, with the researcher taking on an observer role for data collection purposes. 1-2 facilitators guided 1-2 participant groups through the trainings, and 1-2 notetakers per table took written notes on discussions and findings.

c) Short post-training questionnaire: participants shared their perception on what they retained from the capacity building trainings and made recommendations on improvements of the trainings especially in regard to the objective of providing an integrated and collaborative approach to sustainability, emergency management and resilience. This was done in a similar process as in a) with similar focus and structure.

d) Semi-structured post-training discussion: At the end of each training, participants shared their thoughts on satisfaction with the trainings, suggestions for improvements and lessons learned in a group discussion.

To answer the last research question (regarding adjustments of the trainings to create an integrated capacity building program), insights gained from the preceding steps (literature on competencies and assessment of the capacity building trainings) were drawn on and compared to the answers given in the questionnaires and the observations and audio-recordings.

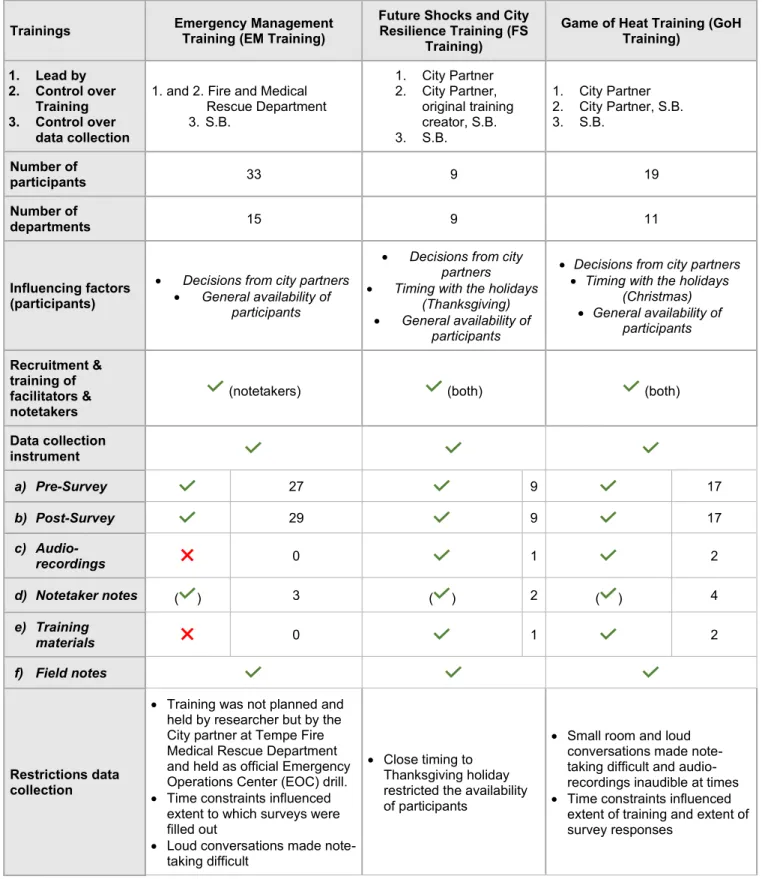

Table 2 shows the trainings held, the data collection process, types and amount of data collected, number and types of participants and training sources as well as information on helpers for the trainings.

Table 2: Information on training set-ups and data collected Trainings Emergency Management

Training (EM Training)

Future Shocks and City Resilience Training (FS

Training)

Game of Heat Training (GoH Training)

1. Lead by 2. Control over

Training 3. Control over

data collection

1. and 2. Fire and Medical Rescue Department 3. S.B.

1. City Partner 2. City Partner,

original training creator, S.B.

3. S.B.

1. City Partner 2. City Partner, S.B.

3. S.B.

Number of

participants 33 9 19

Number of

departments 15 9 11

Influencing factors (participants)

• Decisions from city partners

• General availability of participants

• Decisions from city partners

• Timing with the holidays (Thanksgiving)

• General availability of participants

• Decisions from city partners

• Timing with the holidays (Christmas)

• General availability of participants Recruitment &

training of facilitators &

notetakers

(notetakers) (both) (both)

Data collection instrument

a) Pre-Survey 27 9 17

b) Post-Survey 29 9 17

c) Audio-

recordings 0 1 2

d) Notetaker notes ( ) 3 ( ) 2 ( ) 4

e) Training

materials 0 1 2

f) Field notes

Restrictions data collection

• Training was not planned and held by researcher but by the City partner at Tempe Fire Medical Rescue Department and held as official Emergency Operations Center (EOC) drill.

• Time constraints influenced extent to which surveys were filled out

• Loud conversations made note- taking difficult

• Close timing to Thanksgiving holiday restricted the availability of participants

• Small room and loud conversations made note- taking difficult and audio- recordings inaudible at times

• Time constraints influenced extent of training and extent of survey responses

• Due to the official nature and for security reasons no audio- recordings were made

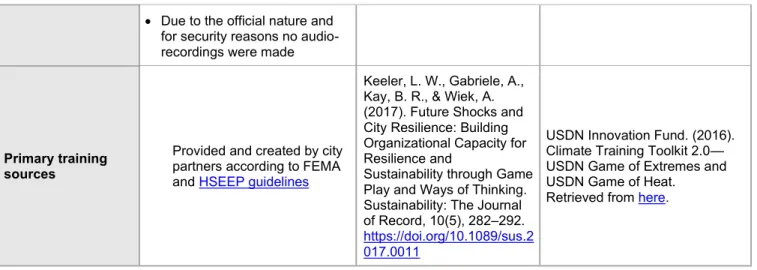

Primary training sources

Provided and created by city partners according to FEMA and HSEEP guidelines

Keeler, L. W., Gabriele, A., Kay, B. R., & Wiek, A.

(2017). Future Shocks and City Resilience: Building Organizational Capacity for Resilience and

Sustainability through Game Play and Ways of Thinking.

Sustainability: The Journal of Record, 10(5), 282–292.

https://doi.org/10.1089/sus.2 017.0011

USDN Innovation Fund. (2016).

Climate Training Toolkit 2.0—

USDN Game of Extremes and USDN Game of Heat.

Retrieved from here.

Legend:

S.B.=Susila Bhagavathula

N/A=not applicable, because no training or data collection was held

= data was collected and used for analysis

( ) = data was collected but was only partially useful for analysis

=no data collected

2.2. Data analysis

Different types of data were collected: audio-recordings in mp3 or mpeg-4 audio files, manually written surveys and game materials and digital notes by notetakers in docx-format during the trainings. Field notes were taken of the trainings, preparations, conversations and meetings with Tempe city staff, job shadowing of the Sustainability Director and general impressions while reviewing literature and the data.

For the analysis of the data, a codebook was created with project objectives, competencies and research questions in mind. This was informed by the project partners in the Tempe city government. The codebook for the KCS was primarily based on Wiek et al. (2011) and was informed and Wiek et al. (2016) and by an internal working paper by Dr. Katja Brundiers and Jordan King from the School of Sustainability at Arizona State University. The codebook for the NGCC was mainly based on Feldmann-Jensen et al. (2019). With this, a deductive analysis was done for each data type and each research question (RQ), as presented in Table 3 below. Once the data was analyzed using the pre-determined codes, the data was again analyzed for inductive codes.

Table 3: Data collection and analysis methods to answer research questions RQ intended

to answer Data collected Data collection instrument (as

presented in Table 2) Analyzation method

RQ 1

Knowledge of which frameworks of competencies exist

Literature on key competencies

Use of existing literature and search in known data-bases such as Web of Knowledge, Google Scholar and other literature platforms such as Elsevier, ScienceDirect, and Springer Professional.

RQ 1 Competencies

entailed in

trainings as part Pre-designed training materials a. and b. Training materials were appraised on which competencies

of design

intension a. Game materials (facilitator guides and gameboard/ game cards) b. EM training guidebook

were entailed using the qualitative data analysis (QDA) software f4analyse

RQ 3 (1) and RQ 3 (2)

Responses to pre-defined questions on competencies that are claimed to be already part of work and processes

Pre- and post-surveys with pre- defined questions (multiple choice and open-answer questions)

Numerical data analyzed in Microsoft EXCEL

Text data was analyzed in f4analyse, using the codebook created

RQ 3 (2)

Competencies build through trainings;

feedback on training experience

Free expressions and

conversations captured through audio recordings

Transcribed by OTTER- software, relistened to correct and edit transcription errors and then analyzed in f4analyse using the codebook created.

All RQs

Contextual information for

general analysis Field notes and notetaker notes

Supplementary material, revised during coding of text and

interpretation of data (text and numerical)

2. Results

The results in general show that firstly, all KCS and all of the NGCC were entailed in at least one of the training instructions and were addressed by participants in at least one of the three trainings.

Secondly, participants self-reported that all KCS were already part of the city governments’

processes to varying degrees. Thirdly, the comparison of both competency sets suggests that the KCS and NGCC have overlaps as well as distinct differences. Fourthly, participants’ satisfaction with the trainings individually and combined as training program were high, however, recommendations for improvements were made and the need for more trainings was expressed.

Results are presented according to the four research questions of which competencies are entailed in the three selected trainings, which are already existing within the city government and which are further built through the trainings and lastly, how the three trainings can be integrated into one capacity building program and suggestions for improvements (RQ 1, 3, 2 and 4).

3.1. Which of the competencies in the existing frameworks in sustainability, emergency management and resilience are entailed in select capacity building trainings for local governments and how do the frameworks relate to each other?

3.1.1. Overview of Key Competencies in Sustainability found in the design of each training

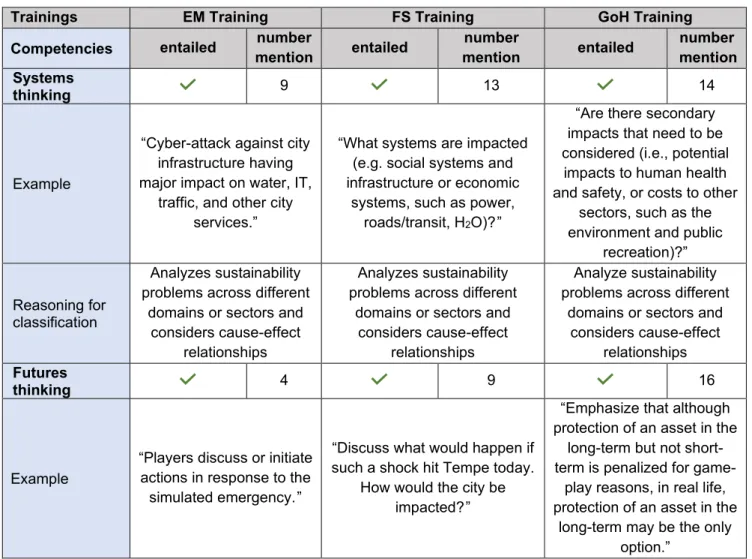

Key findings show that the three trainings in their design entail [core] aspects of all KCS, as visible in Table 4 below. The interpersonal/ collaborative competency in the EM training instructions is the only competency that was fully entailed. In contrast, all other competencies were only partially expressed in the three training instructions (as not all aspects defining this competency were entailed) (see section 3.1.1.1 ff). Values thinking was the competency, which was most entailed within all trainings (largest number of aspects), whereas futures-thinking competency and strategic-thinking competency were entailed the least (lowest number of aspects).

Except for the FS training, none of the other two trainings were specifically designed with KCS in mind, as stated by the training creators and in the training materials.

Table 4 presents information on whether a competency was entailed, the number of times it was mentioned, an example from the training materials and the explanation why the example refers to the competency mentioned.2 In the following, aspects that describe key competencies are presented for each training and missing aspects in the trainings that are crucial when conveying competencies are highlighted.

Table 4: Key competencies in sustainability (by Wiek et al. (2011)) found in the design of each of the selected trainings

Trainings EM Training FS Training GoH Training

Competencies entailed number

mention entailed number

mention entailed number mention Systems

thinking 9 13 14

Example

“Cyber-attack against city infrastructure having major impact on water, IT,

traffic, and other city services.”

“What systems are impacted (e.g. social systems and infrastructure or economic

systems, such as power, roads/transit, H2O)? ”

“Are there secondary impacts that need to be considered (i.e., potential

impacts to human health and safety, or costs to other

sectors, such as the environment and public

recreation)?”

Reasoning for classification

Analyzes sustainability problems across different

domains or sectors and considers cause-effect

relationships

Analyzes sustainability problems across different

domains or sectors and considers cause-effect

relationships

Analyze sustainability problems across different

domains or sectors and considers cause-effect

relationships Futures

thinking 4 9 16

Example

“Players discuss or initiate actions in response to the simulated emergency. ”

“Discuss what would happen if such a shock hit Tempe today.

How would the city be impacted? ”

“Emphasize that although protection of an asset in the

long-term but not short- term is penalized for game-

play reasons, in real life, protection of an asset in the

long-term may be the only option.”

2 The results count only the times when aspects related to a key competency were mentioned, they did not count the number of aspects pertaining to this competency. For example, the instruction in the GoH Facilitator Guide said (p.2):

“Allow for time at the beginning and at the end for participants to share what they are doing in their own cities on the topics discussed in the game” (USDN Innovation Fund, 2016). It refers to the interpersonal competency (one count) although within this competency, two different aspects were entailed: the need for (1) teamwork, as the game is based on group activities which includes this activity and (2) articulating the roles, responsibilities and contributions of different stakeholder groups to effective sustainability problem solving. While both describe different facets of interpersonal competency, this was counted as 1, leading to the overall number of competencies mentioned being smaller than the individual concepts or tasks applied.

Reasoning for classification

Considers potential responses to scenario,

including prevention, mitigation, and adaptation

responses

Ability to anticipate how sustainability problems might

evolve or occur over time (scenarios)

Considering how futures thinking informs strategy

building Values

thinking 11 9 26

Example

“Participating agencies may need to balance exercise play with real- world emergencies. Real-

world emergencies take priority.”

“Are there any synergies and trade-offs between the

priorities? ”

“[…] Defin[e] high, medium and low exposure, sensitivity and adaptive

capacity .”

Reasoning for classification

Weighs values in various processes, including visioning, assessment,

and evaluation

Considers trade-offs and 'win- win' synergies

Weighs values in various processes, including visioning, assessment, and

evaluation Strategic

thinking 10 7 13

Example

“Post-exercise debriefings aim to collect sufficient relevant data to support effective evaluation and improvement planning.”

“[…] share out [your asset] to the group […] and how […] it helps address the issue and achieve the city’s strategic

priorities”

“What are the main barriers to implementing the strategy, e.g., funding, political will (or political opposition), lack of data, permitting, and how would

you overcome these barriers?”

Reasoning for classification

Considers and executes concepts of programme planning and evaluation

Develop plans to leverage assets, mobilize resources, and coordinate stakeholders

The ability to overcome systemic inertia, path dependencies and other barriers to reach envisioned

outcomes.

Interpersonal/

collaborative 13 9 14

Example

“Discuss the capability to communicate and coordinate effectively with

Regional, County, and Federal partners during

an active emergency .”

“Assign roles to the group participants so that the writing

process can be shared.”

“Encourage the players to consider their role carefully

and get into character to advocate for the assets

they find most critical.”

Reasoning for classification

Ability to successfully collaborate with various

stakeholders from government, business

and civil society

Articulate the roles, responsibilities and contributions of different stakeholder groups to effective

sustainability problem solving

Demonstrates and builds empathy including perspective taking and immersive experiences

3.1.1.1. Entailed and Missing Aspects of Key Competencies in Sustainability in the Design of the Emergency Management Training

For the EM training, aspects of systems thinking were entailed in the instructions, leading to the competency being referenced a total of 9 times (see Table 4). However, the competency was not

entailed entirely, as critical concepts of systems thinking—such as the use of a systems perspective to test transition strategies, analysis of tipping points, and resilience measures across different scales/domains—were not entailed. These are important in regard to emergency management preparedness, mitigation and recovery efforts, because these activities are more effective if looked at holistically in consideration of the bigger picture.

Further, aspects of futures thinking competency were entailed, with the competency being referenced 4 times. As critical aspects were not entailed, in particular considerations of visions and/ or non-invention scenarios, this competency was not entailed completely either.

Considerations of visions and/ or non-invention scenarios are essential for a thoughtful disaster recovery plan, as any plan should not only envision the future and steps to achieve it, but also consider what the effects of inaction would be.

The values thinking competency was referenced a total of 11 times. Though normative orientations were given within the instructions, concepts of justice, equity, responsibility, and fairness were not considered nor do the instructions entail ethical and moral considerations. These aspects are important especially in regards to thoughtful disaster recovery planning or sustainability efforts, such as conservation, as these efforts need to include considerations beyond the individual self and need to evaluate in which context possible and meaningful actions take place and in consideration of contributors and affected (i.e. the environment, species and future generations).

Though aspects of strategic thinking competency were entailed, with the competency being referenced 10 times, the competency was not entirely entailed in the instructions, as concepts describing strategic thinking competency, such as the ability to overcome systemic inertia, path dependencies and other barriers to reach envisioned outcomes, were not mentioned.

Nevertheless, these are important for all four phases of emergency management and especially resilience planning and building in order to see and solve current problems and move beyond already existing structures that cause these problems.

The interpersonal/ collaborative competency was referenced a total of 13 times and was thus the most entailed competency. All main aspects were entailed. It is therefore the only competency that is entailed entirely in the instructions of this training.

3.1.1.2. Entailed and Missing Aspects of Key Competencies in Sustainability in the Design of the Future Shocks and City Resilience Training

For the FS training mentions of systems thinking competency were made a total of 13 times (see Table 4). Despite being the most referenced competency in this training, critical aspects, such as the use of a systems perspective to test transition strategies, considerations of tipping points, and resilience measures across different scales/domains were not considered. This can be seen as disadvantageous, given that the same critical concepts are missing in the EM training as well. In addition, the use of systems concepts, such as ontologies, cause-effect structures, cascading effects, inertia and feedback loops were not entailed either which are important in regards to the understanding of plans and developing of strategies in emergency management preparedness, mitigation and recovery efforts as well as sustainability efforts.

Aspects of the futures thinking competency were entailed, with the competency being referenced 9 times. While most aspects of this competency were mentioned in the instructions, similarly to the EM training, considerations of visions and/ or non-invention scenarios were not entailed in the FS training instructions either. These however are essential for robust disaster recovery planning, as highlighted in the EM training.