www.giga-hamburg.de/workingpapers

___________________________

The EU’s Foreign Policy after the Fifth Enlargement:

Any Change in Its Taiwan Policy?

Günter Schucher

N° 42 February 2007

Edited by GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies / Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien.

The Working Paper Series serves to disseminate the research results of work in progress prior to publication to encourage the exchange of ideas and academic debate. An objective of the series is to get the findings out quickly, even if the presentations are less than fully polished. Inclusion of a paper in the Working Paper Series does not constitute publication and should not limit publication in any other venue. Copyright remains with the authors.

When Working Papers are eventually accepted by or published in a journal or book, the correct citation reference and, if possible, the corresponding link will then be included in the Working Papers website at:

www.giga-hamburg.de/workingpapers.

GIGA research unit responsible for this issue: Institute of Asian Studies

Editor of the GIGA Working Paper Series: Bert Hoffmann <hoffmann@giga-hamburg.de>

Copyright for this issue: © Günter Schucher

Editorial assistant and production: Verena Kohler and Vera Rathje

All GIGA Working Papers are available online and free of charge at the website:

www.giga-hamburg.de/workingpapers. Working Papers can also be ordered in print. For production and mailing a cover fee of € 5 is charged. For orders or any requests please contact:

E-mail: workingpapers@giga-hamburg.de Phone: ++49 (0)40 - 428 25 548

GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies / Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien Neuer Jungfernstieg 21

20354 Hamburg Germany

E-mail: info@giga-hamburg.de Website: www.giga-hamburg.de

The EU’s Foreign Policy after the Fifth Enlargement:

Any Change in Its Taiwan Policy?

Abstract

On 1 May 2004, the world witnessed the largest expansion in the history of the European Union (EU). This process has lent new weight to the idea of an expanded EU involvement in East Asia. This paper will examine the question of whether there has been a change in the EU’s foreign policy with respect to its Taiwan policy after the fifth enlargement. It analyses the EU’s policy statements on Asia and China to find evidence. The political be- haviour of the EU has not changed, although there has been a slight modification in rheto- ric. The EU – notwithstanding its claim to be a global actor – currently continues to keep itself out of one of the biggest conflicts in East Asia. The new members’ interests in the East Asia region are too weak to alter the EU’s agenda, and their economic priorities are rather linked to the programmes of the EU than vice versa.

Key words: EU, enlargement, Central and Eastern European countries, foreign policy, China, Taiwan

JEL classification: F13, F51, F59

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 23rd Taiwan-European Conference:

'The Emerging Global Role and Tasks of the European Union', in Taipei, Taiwan, 19-20 December 2006. I would like to thank Francis Kan and the Institute of International Rela- tions, National Chengchih University, for the invitation. I am also grateful to Fu-chang Chang for his remarks as a discussant and to my colleague Dirk Nabers for his helpful and encouraging comments.

Dr. Günter Schucher

is director of the GIGA Institute of Asian Studies (IAS) in Hamburg. As a member of the GIGA research group on “transformation in globalization” his research focuses on social issues in the PRC, especially the Chinese labour market, and cross-strait relations. Dr.

Schucher is the treasurer of the German Association of Asian Studies and editor of the refereed journal ASIEN.

Contact:schucher@giga-hamburg.de, website: http://staff.giga-hamburg.de/schucher.

Die Außenpolitik der EU nach der fünften Erweiterungsrunde: Hat sich die Taiwan- politik geändert?

Mit zehn neuen Mitgliedsstaaten erfuhr die Europäische Union (EU) am 1. Mai 2004 ihre größte Erweiterung seit Gründung. Schon der Erweiterungsprozess hatte Vorstellungen genährt, die EU werde ihr Engagement in Ostasien verstärken und könne auch mehr zur Lösung des chinesisch-taiwanischen Konflikts beitragen. Dieser Artikel geht am Beispiel der Taiwanpolitik der EU der Frage nach, ob im Zuge der Erweiterung eine Änderung der Außenpolitik der EU festzustellen ist. Eine Analyse der offiziellen Dokumente lässt keinen grundsätzlichen Wandel erkennen, allerdings eine leichte Modifizierung in der Darstel- lung des Konflikts. Die EU hält sich trotz ihres Anspruchs, ein globaler Akteur zu sein, auch weiterhin aus einem der größten Sicherheitsprobleme in Ostasien heraus. Die Inte- ressen der neuen Mitglieder in Ostasien sind zu schwach, um die außenpolitische Agenda der EU zu ändern; diese sehen im Gegenteil ihre ökonomischen Belange eher mit der bis- herigen EU-Politik verbunden.

Günter Schucher

Article Outline 1. Introduction

2. The Impact of Enlargement on Foreign Policy

3. Five Arguments for a Possible Modification in the EU-25’s Policy towards Taiwan 4. Five Arguments against Any Modification

5. The European Parliament as a Proponent of a New Policy towards Taiwan 6. The EU’s Policy Statements: Nothing New but Rhetoric

7. The Paradigmatic Debate about the Arms Embargo 8. Do Economic Relations with Taiwan Have Any Impact?

9. The CEECs’ Relations with Taiwan

10. Conclusion: Still Just Talking Business…

1. Introduction

On 1 May 2004, the world witnessed the fifth round of enlargement and the largest expan- sion in the history of the European Union (EU). The EU-15 incorporated ten new member states, most of them being Central and Eastern European countries (CEECs), including the Baltic states.1 It would seem to be a matter of common sense that the EU-25 will play a larger role in global politics than the EU-15 – not in small part due to its increased weight in inter-

1 Ten countries have joined: Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia from the so-called Visegrad ‘bloc’ (V4); Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania from the Baltic region; Slovenia from the for- mer Yugoslavia, and Malta and Cyprus from the Mediterranean. As far as not otherwise specified, this contribution will only take the CEEC into account. On 1 January 2007, two more CEE coun- tries joined the EU: Romania and Bulgaria.

national trade and business relations. This corresponds well with the EU’s own ambition to enhance its global influence and is also supported by the new member states. The EU enlargement process has stimulated several studies about a change in the nature of EU’s for- eign policy (see, e.g., Carlsnaes et al. 2004, Edwards 2006, Král 2005, Marsh and Mackenstein 2005, Missiroli 2002, Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier 2005, Sedelmeier 2003).

Enlargement has also lent new weight to the idea of an expanded EU involvement in East Asia and its eventual development into a significant partner in that region, in particular in untangling the Taiwan issue (Schubert 2003, Cabestan 2006, Lan 2004). Time and again poli- ticians and academics in Taiwan as well as in Europe have called upon the European Union (EU) to contribute to a political solution regarding the cross-Strait tangle. Fully aware of the EU’s political stance on the Taiwan issue and having yet to question the EU’s ‘one China’

policy, these actors nevertheless see room to extend the EU’s role in Asia, an objective for which Brussels is also striving.

In accordance with its ‘one China’ policy, the EU does not recognise Taiwan as a sovereign state, but as an economic and commercial entity. It has solid relations in the economic arena and other non-political fields such as science, research, education or culture. The EU is Tai- wan’s fourth most important trading partner, while Taiwan is the fourth largest trading partner for the EU in East Asia (EETO 2006).

This article will examine the question of whether there has been a change or, in the very least, a modification in the EU’s Taiwan policy after the fifth enlargement. By doing this it may make a small contribution to the broader issue whether enlargement has changed the very nature of EU foreign policy. To begin, I will make some brief comments on the EU’s foreign policymaking in the second section (2). In order to frame the question as to the pos- sible impact of enlargement, I will present five arguments that might speak for a modifica- tion (3). Opposing arguments can, however, also be outlined (4). In what follows, this paper gives a brief look at the EU Parliament’s (EP) debates on Taiwan (5). The EP is a pronounced supporter of Taiwan in international politics, but its role in the EU system is rather marginal.

That becomes clear in an analysis of the EU’s policy statements on Asia and China (6). I ar- gue that the political behaviour of the EU has not changed after the enlargement, although there has been a slight modification in rhetoric. The debate surrounding the lifting of the Chinese arms embargo is taken as a paradigmatic case to show the limited impact of enlargement (7). Section 8 provides a glimpse at the new members’ economic relations with Taiwan that seem to have little impact on their stance towards the cross-Strait issue. And fi- nally, I will outline the new member states’ Taiwan/China policy (9).

Wrapping up all the different aspects, I come to the conclusion that the EU – notwithstand- ing its claim to be a global actor – currently continues to keep itself out of one of the biggest

conflicts in East Asia (10). Some indicators, however, point at its relatively more distinct per- ception of the tangle.

Compared to the EU’s relations with China, its Taiwan policy could be seen as merely of minor relevance. Cross-Strait relations, however, could very easily change for the worse, producing dramatic effects on the world’s security. The EU cannot afford to be wittingly negligent in this area while simultaneously maintaining its hopes to establish itself as a global actor. Thus the results of this analysis will also help us to improve our understanding of foreign policymaking in the EU.

2. The Impact of Enlargement on Foreign Policy

Most of the studies on EU enlargement focus on politics of the applicants, the member-states or the EU and the impact that enlargement or the pre-accession process has had or will have on the EU as a whole and specifically older and more recent members, including areas such as ‘identity, interests, and behaviour’ (Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier 2005). This contribu- tion, however, deals with the impact of enlargement on the EU’s policy towards Taiwan, which calls for some remarks on the EU’s foreign policy and on the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) – not only because the present focus lies on political relations with Taiwan and China respectively, but also because of the peculiar nature of European foreign policy.2

Policy towards Taiwan refers to the specifically political dimension of foreign policy and has to be distinguished from the more general notion of ‘external relations’. The latter includes the foreign economic policy dimension as well. Activities of the EU are divided into differ- ent ‘pillars’; the CFSP is located in the second pillar of the EU. Policymaking is thus not ac- complished by the supranational ‘Community method’ of decision-making (first pillar), but rather an intergovernmental process controlled by the member states. This implies that it also does not equate with the sum of the foreign policies of the member states themselves.

The CFSP was introduced rather late; namely in 1992 when the European Policy Coordina- tion was upgraded to CFSP in the Treaty of Maastricht. It is constructed as a framework within which most of the EU’s foreign and security issues are handled, consensus forming the central prerequisite. One of the declared objectives of CFSP was to develop and consoli- date democracy and the rule of law, as well as to cultivate respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms (Marsh and Mackenstein 2005: 60f.). The creation of the High Repre-

2 In foreign policy analysis there is a difference between ‘European foreign policy’ and the more re- strictive ‘EU foreign policy’ (see White 2004: 11-31). In this contribution we discuss the EU’s for- eign policy and use both terms interchangeably.

sentative for CFSP put a ‘face’ on the EU in the arena of international relations. Neverthe- less, there are different actors within the second pillar which limit the EU’s ability to react to international events (ibid.:254).

Foreign policy is generally conceived by scholars as actions taken by governments directed at the environment external to their state. The EU, however, is not a state with relatively clear boundaries. To view it as an actor and a unitary entity in foreign policy is thus a lim- ited perspective. Nor is European foreign policy constituted by the respective foreign poli- cies of member states. It must instead be conceived as a two-way relationship between na- tional foreign policies and EU policy.3 Because of this very special structure, it remains a constant challenge for the EU to translate its policy into effective action (Marsh and Macken- stein 2005: ch.3).

Another challenge is the development of a common foreign policy. As White puts it very clearly, ‘the key analytical questions here are to what extent is European foreign policy shaped by national policies and to what extent have national foreign policies themselves been transformed or ‹Europeanised› by operating over many years within an EC/EU institu- tional context?’ (White 2004: 16). For White the concept of ‘Europeanisation’ connects the different levels of analysis (European vs. state levels), since it takes into account the influ- ence of member states on European policymaking as well as the impact of EU processes on national systems (White 2004: 20f.). He characterises Europeanisation as the process by which the CFSP on the one side and the interests and policies of the individual states on the other move closer toward a common set of EU norms, i.e., as a ‘reciprocal relationship’

(White 2004:28). In Sjursen’s words, ‘the clear distinction between the ‹national› and the ‹Eu- ropean› might gradually be blurred’ (Sjursen 1998).

In part of the literature, however, Europeanisation is seen rather one-dimensionally – either as a top-down process, that is, as the impact of the EU on domestic structures and institu- tions (‘Brusselisation’) or as an elevation of certain aspects of national foreign policies to EU policymaking (Joergensen 2004: 41f., 48ff.). For example, Wong argues that there is a strong trend towards convergence in the China policy of the member states. His conclusion sup- ports the concept of Europeanisation, that the acquis of the CFSP increasingly shows dis- cernible impact on the foreign policies of EU states. Notwithstanding a certain incoherence in its CFSP, the EU’s effect on individual national policies has been more significant than commonly imagined. Wong’s argument gains weight by the EU’s own testimony that China is the centrepiece of its policy in Asia. Over time, he expects even more coordination reflexes to come about (Wong 2005).

3 By including the international dimension, Jørgensen (2004: 32-56) even speaks of three kinds of re- lations.

In this paper, EU foreign policy is understood as an interacting system of action. In the af- termath of enlargement the number of policies and bilateral relationships has expanded. The question is whether enlargement has changed the very nature of EU foreign policy, here with respect to Taiwan. But how can we know whether this has happened? After presenting some arguments that speak for or against a significant impact, I will take a look at EU state- ments in order to analyse whether new issues in relations to Taiwan and China are ad- dressed or if new answers to known issues have been created. I do not expect any dramatic changes, but could imagine minor modifications.

The arguments presented are related to the different dimensions of EU foreign policy, the national as well as the European. They are derived from various contributions on the EU’s foreign policy disregarding their position in International Relations theory. Thus, they rely on different approaches.

3. Five Arguments for a Possible Modification in the EU-25’s Policy towards Taiwan First Argument: The EU’s New Global Ambitions and Security in East Asia

The fifth enlargement increased the global weight of the EU. Already in the course of acces- sion negotiations, the EU had expressed its ambitions to gain more potential power in global affairs. In assessing the EU’s external relations, it can be established that relations with Asia have risen to an unparalleled level in recent years. Communications from the EU Commis- sion published in 1994 and 2001 emphasised the rapid economic changes that had taken place in the region. The EU is seeking to strengthen its political and economic presence in Asia and to raise this ‘to a level commensurate with the growing global weight of an enlarged EU’ (Commission 2001: 15). Accordingly, the EU’s policy in Asia is a sort of litmus test for its global ambitions. In the same communication cited above, the EU commits itself to promoting stability and security in East Asia. Without a doubt, the dispute across the Taiwan Strait is one of the major threats to peace and stability in East Asia, which has been acknowledged only recently by the incumbent Commissioner for External Relations (Fer- rero-Waldner 2005). As a global civilian power, the EU can play a bigger role in conflict reso- lution, and it can present its own proposals for de-escalating the tensions across the Taiwan Strait.

Second Argument: The EU as a Promoter of Democracy

The enlargement strengthened the EU’s identity as a promoter of human rights and democ- racy. The first of the so-called ‘Copenhagen Criteria’ of 1993 is the requirement of stable in-

stitutions that guarantee democracy, rule of law and human rights. Therefore, enlargement policy has been a great success with respect to the promotion of European democracy in and of itself and has specified the EU’s role in the protection of human rights and democracy (Sedelmeier 2003). Besides long-term trade prospects, extending the values of democracy, the rule of law and human rights as well as geopolitical stabilization were additional moti- vating factors behind the EU’s enlargement strategy (Matlary 2004, Moravcsik and Vachu- dova 2005).

The spread of democracy also has a particularly nice ring to it in the new member states, which suffered from the effects of non-democratic rule for decades. This becomes obvious in different views on the EU’s relations with Russia (Edwards 2006). The strengthened democ- ratic identity might have some implications for the EU’s position regarding the authoritarian regime of the PRC on the one hand and the democratic regime of Taiwan on the other. Pres- sure on China to adopt political reforms that will ultimately lead to the establishment of a democratic society might increase.4

Third Argument: EU Integration as a Role Model

The EU’s integration process in itself is seen by Asian countries and also by China and Tai- wan as a role model for Asian integration. Some regard it as a role model with respect to China-Taiwan integration as well (Clark 2003; Schucher and Schüller 2005). That would suggest that the EU could strengthen its position in Asia by exporting its model of regional cooperation. The same holds true for the principles of regionalism and multilateralism ad- vocated by the European Union (Reiterer 2006). Bersick emphasizes the value of inter- regional cooperation within the overall framework of the ASEM process as a way for the EU to project European soft power to East Asia, to take part in the moulding of an evolving East Asian regionalism (by co-defining norms, rules and principles), and to balance Chinese soft power. That approach is mainly characterised by institution building, in which Taiwan is as- cribed a participant role (Bersick 2006a; 2006b; 2006c; see also Gilson 2005).

Fourth Argument: The Pro-Atlanticism of the New Member States

The United States have been at the centre of the China-Taiwan dispute ever since it began.

The new member states are admittedly more Atlanticist-oriented than the old ones and many of them accord a high priority to close ties with the USA and the maintenance of strong transatlantic bonds (Jelonek 2006; Edwards 2006). As their views filter into the EU’s

4 Some Chinese authors seem to adhere to this belief as well (see Weigelin-Schwiedrzik and Noes- selt 2006: 53, 63).

CFSP, there will possibly be more room for Washington’s arguments. Washington opposes unilateral changes to preserve peace and stability in the Strait. Its interest in ensuring that Taiwan has the capabilities to safeguard its future not only translates in military back up, but also in unequivocal calls on Beijing to cease its arms build-up opposite Taiwan and to reduce its armed threat to Taiwan (see, e.g., Clifford A. Hart, Jr. 2006).

Fifth Argument: Taiwan as an Attractive Economic Partner

At least some of the new member states have an economic interest in East Asia. Compared to the predicted commercial gains with the PRC, trade with Taiwan seems to be negligible.

Growth rates in the CEEC’s trade with the island, however, exceed those of trade with the mainland. Moreover, the new member states have a different production pattern than the old members. Their production structures are less complementary, but more similar to China, which means that more developed provinces of the PRC are strong competitors in terms of low-cost labour (and thus foreign direct investments [FDI] from the EU countries).

Therefore the entrants might well be interested in expanding business relations with Tai- wan, especially when it comes to attracting FDI.

To back up these arguments, it might be interesting to note that Chinese authors judging the enlargement and the development of the EU’s institutions, including the CFSP mechanism, are not unreservedly optimistic about the China-EU relationship. Zhang (Zhang 2006) ar- gues that the enlargement will complicate Sino-EU relations, although it will not slow down the move towards a strategic partnership for either side. According to Yang, enlargement will not only change the power structure of the EU and influence its pattern of decision- making; the new member states also tend to prefer closer ties with the USA. Furthermore, they are economic competitors of China, which will lead to the occurrence of more disputes on trade than ever before (Yang 2006).

4. Five Arguments against Any Modification First Counter-argument: Limited Interest in East Asia

The Sino-Taiwanese dispute has never triggered any public debate in Europe and the Euro- pean countries have never been involved in the settlement of the Taiwan issue. This will not change when the entrants bring their own interests into the EU’s external policies. Due to past experience and their own geographical situation, the CEECs have a stronger interest in the ‘Eastern dimension’ of the EU’s foreign policy than in other dimensions. Most of the en- trants are not engaged in any bilateral contacts with China that go beyond economic coop-

eration. The only issues that stirred up some controversy during the particularly long pre- accession process were those involving relations with fellow applicants and/or neighbours.

Even the pro-Americanism of the new members is often directly proportional to anti- Russian sentiments. None of the entrants have pronounced overseas interests (Missiroli 2002: 58ff., Missiroli 2004: 2).

Second Counter-argument: Economic Interests in China Dominate

Relations with Taiwan are governed by the scope of EU-China relations. The development and stability of China is a major concern of the EU. Relations with China are dominated principally by economic aims and less by security concerns. The EU treats China as a strate- gic partner and China sees Taiwan as an internal issue. Therefore, the EU is very careful in touching on the Taiwan issue in order not to jeopardize its engagement policy with China.

That attitude is underpinned by China’s EU policy paper of 2003, in which it is made clear that a proper treatment of the Taiwan question is essential for the steady growth of China- EU relations. In view of the new members’ small share in EU trade, Brussels is not going to change its China policy. This is reinforced by the EU’s preference to mark its presence in the international system through its external economic relations and less through the CFSP.

Third Counter-argument: Constrained Means for Interventions

Even if the EU is willing to promote security in the Taiwan Strait, its means for interventions are restricted. Whereas the EU could use the accession process to steer the CEEC’s transfor- mation, e.g. granting aid to developing countries under the condition of concessions in hu- man rights and democracy, there are no comparable mechanisms which would allow a simi- lar exercise of political leverage in the case of China. Analyzing the strategy papers of the re- spective parties, Weigelin-Schwiedrzik and Noesselt go as far as to compare the obvious asymmetry in the official partnership between the EU and China with a relatively simple form of barter: in exchange for its far-reaching demands for political reforms in China, the EU refrains from interfering in China’s Taiwan policy (Weigelin-Schwiedrzik and Noesselt 2006: 64).

Serious doubts about the EU’s ability to project soft power in the Far East are also expressed by Laursen (2006:24) and Möller. ‘Internal and external conditions presently do not favour the emergence of a Eurasian world order centred on soft power’ (Möller 2006: 15). Soft power in Nye’s conceptualization is not only the ‘ability to influence the behaviour of others to get the outcomes on wants’, it is also ‘attractive power’ (emphasis – GS) and as such re- lated to hard power (Joseph S. Nye 2004: 2, 6f.).

Fourth Counter-argument: Incoherent Foreign Policy

The EU’s CFSP is not coherent and the foreign-policy machinery lacks co-ordination. With the democratisation of its institutions, decision-making has become even more complex and the EU facing ever growing difficulties to find a cohesive voice. That does not mean that de- cision-making has become less efficient. Nevertheless, due to greater uncertainties regarding the positions being adopted in national capitals, the members’ behaviour in the Council and the Commission has become more unpredictable (Edwards 2006: 155f.). Moravcsik and Va- chudova argue that during the pre-accession process the new applicants were in a weaker bargaining position because they were likely to receive greater benefits from enlargement.

Although their power might have improved since they have joined and the diversity of in- terests has increased, these developments would not affect any major alteration in the EU’s politics. Their accession is more likely to have reinforced existing trends in EU politics (Mo- ravcsik and Vachudova 2005).

Moreover, the importance attached to the assumed pro-Atlanticism of the new entrants might have been overestimated. As Král shows, the new member states have not automati- cally sided with the US in foreign policy issues. Neither have they acted as a homogenous bloc in shaping the CFSP. There is no united ‘New Europe’, but a region divided by certain lines. On the one hand, the three Baltic republics and Poland strongly emphasize a CFSP compatible with US policies and prioritise EU external action in the East, namely towards Russia and the Ukraine. For the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Slovenia, the issue of developing a coherent policy towards Russia is far less important, and their Atlanticist commitment is not equally intense. Citing the idealism in the new member states’ foreign policy and the expectation of their greater emphasis on human rights, democracy and rule of law in dealing with other countries, Král (2005) predicts that this phenomenon is not likely to endure and will probably give way to a pragmatic approach.

Fifth Counter-argument: The Negligible Economic Weight of the New Entrants

With exception of Poland, all of the new entrants are relatively small countries. Therefore their share in EU trade is rather small. Although they experience the most impressive annual growth rates in bilateral trade with Taiwan in the EU, this is hardly transformed into politi- cal outcomes, particularly since their trade with China is much greater. Economic relations with China are growing; but, on the one hand all of the entrants experience a quite large trade deficit and on the other hand trade and investment within Europe dominates.5

5 In the Baltic States, e.g., some 60-80% of all FDI originates from another Baltic Sea Region country and capital flows in from the West (Liuhto 2005).

5. The European Parliament as a Proponent of a New Policy towards Taiwan

The EU Parliament (EP) has voiced its concern regarding China-Taiwan relations with clear messages emphasising the necessity that China promote human rights and democracy (Lan 2004, Zanon 2005).6 The enlargement increased the number of seats from 626 to 732 and the number of political parties represented in the EP to over 150, which has dramatically ele- vated the organisation’s heterogeneity. As regards human-rights issues and the promotion of democratic values, however, the EP appears united. The same holds true for the Taiwan issue and the rejection of the use of violence in cross-Strait relations.7

In several resolutions the EP showed its approval of the democratic development of Tai- wan and requested that the EU recognise its importance for other Asian countries.

It has repeatedly shown interest in an improved representation of Taiwan in interna- tional organisations (WTO, WHO, WHA) and actively proposed Taipei’s participation in ASEM.

It took Taiwan’s side in the straits conflict and urged China to withdraw its missiles.

Moreover, it raised its objections to Beijing’s anti-secession law and strongly recom- mended that the Council and the member states maintain the embargo on the arms trade with China ‘until greater progress is made on human rights issues in China and on cross-Strait relations’ (P6_TA(2005)0297).

It demanded that the Council extend its relations with Taiwan to political fields.

One concrete issue the EP focused on since 1996 was the opening of an EU representative office in Taipei. This was finally established in March 2003.

Having analyzed the EP’s resolutions, we can agree with Zanon that it is ‘less concerned with the utility of foreign policy for the Member States and more attentive to promoting the values specific to the European Union’ (Zanon 2005). Being mainly a consultative organ, the EP is, however, only a marginal player in the EU system.

The declarations of the EP may hold a symbolic importance since its members (MEPs) are directly elected. It can adopt resolutions under a consultation procedure of international agreements or in response to the Commission’s reports. MEPs can express their views by means of resolutions placed on their own initiative and they can demand a public explana- tion from the Council and the Commission of their policy by posing questions in written or oral form. But the autonomous foreign-policy line of the EP has not had an effect on the EU’s

6 Full documentation is available on the EP’s website at www.europarl.europa.eu.

7 See, for instance, the recent debates on 6 July 2005 and 18 May 2006, the EP’s resolutions ‘On rela- tions between the EU, China and Taiwan and security in the Far East’ (P6_TA(2005)0297) and ‘On Taiwan’ (P6_TA(2006)0228) as well as the respective joint motions for a resolution as of 5.7.2005 and 17.5.2006.

policy so far. The merely symbolic power of the EP in the CFSP is reflected in only mild condemnations and the lack of further action by China.

6. The EU’s Policy Statements: Nothing New but Rhetoric

There is a consensus among EU policy-makers to prioritise democratic and human rights norms over competing concerns in foreign policy. Corresponding behavioural obligations, however, are rather diffuse. The question is how the EU’s self-appointed entitlement to play a larger role in global politics and its enhanced identity (in relation to the promotion of de- mocracy) can be transformed into policy practice. To prove this, we will examine relevant declarations and documents produced by the Council and the Commission. They are the re- sult of compromises by the member states and they also reflect their neglect of certain is- sues. In other words, they ‘can be interpreted as explicit expressions of collective commit- ments or shared understandings’ (Sedelmeier 2003: 15).

6.1. The ‘One-China’ Principle and the Plea for a Constructive Dialogue

In order to meet its objective to strengthen its presence in Asia, the EU Commission declared in its 2001 Communication on European-Asian relations, among others, that Europe wants to contribute ‘to peace and security in the region and globally, through a broadening of our engagement with the region’ as well as ‘to the spreading of democracy, good governance and the rule of law’ (Commission 2001: 15).8 One prominent source of tension or conflict is the unresolved problem ‘across the Taiwan Strait’. Moreover Taiwan ‘is the EU’s (then – G.S.) third-largest bilateral trading partner in Asia’. Nevertheless, while establishing a dia- logue with China on another sensitive topic like human rights, the EU sticks to a hands-off approach concerning Taiwan and leaves the solution to ‘a constructive dialogue’ between China and Taiwan (Commission 2001: 6, 23).9

8 In 1994, the EU published its first strategy paper on Asia. By addressing the whole continent, the EU upgraded its earlier policies towards single countries within Asia. The EU-Asian relationship, however, continued to be foremost about economics (see Marsh and Mackenstein 2005: 233ff.).

9 This type of behaviour describable as a ‘double standard’ can also be found in latest EU press re- leases. In the foreign ministers’ meeting of the EU Troika with China in Vienna the Austrian For- eign Minister Plassnik declared that the ‘partnership is supported by common interests, but also by openness, mutual understanding, and respect. This is also the case for topics on which our opinions differ’. But while the ministers dealt with the human rights issue in some length and de- tail, regarding Taiwan only the Taiwanese president was criticized (Press release 3.2.2006, www.eu2006.at/de/News/Press_Releases/February/0302TroikaChina.html [accessed 27.12.2006]).

The same holds true for ‘State Secretary Hans Winkler at the EU-China strategic dialogue in Bei- jing’ from 6 June 2006. He praised the open, constructive atmosphere in discussion of human

This approach is all the more striking as, firstly, the way the conflict will be solved or even the way this stalemate will be handled in the future will be decisive in determining China’s future role in global affairs, and secondly, the European Union will not remain unaffected by any change in the status quo in the Taiwan Strait. This implies that the EU should adopt a clear stance vis-à-vis a conflict with possible global repercussions if it wishes to be taken se- riously as a dialogue partner as well as an aspiring actor in global security affairs (Ward 2005).

There is no doubt that the EU adheres to the ‘one China’ principle and that none of its mem- ber states recognise Taiwan. At the same time, economic ties with Taiwan are cultivated and approved by the EU and private dialogues are conducted. Brussels and the member states are very cautious about developing relations with Taiwan. Official documents on foreign- policy issues ignore the Taiwan issue, which leads us to the conclusion that it is not a matter of any serious concern to the EU or a topic in the extensive dialogue with Beijing.

The official stance of the EU has obviously not changed since the enlargement, as we can judge by the recent Communication on China and the joint statements of the Europe-China summits. On 24 October 2006, the European Commission adopted its updated strategy to- wards the PRC, which adheres to the fundamental approach of engagement and partner- ship. In its aim to support China’s transition to a more open and plural society, parts of the

‘Communication’ paper are openly critical as regards China’s domestic policy. The paper also encourages full respect of fundamental rights and freedoms in China. In economic rela- tions, the EU even wants to ‘urge’ and ‘press’ China to open up its market and create a level- playing field. As for the Taiwan issue, the paper remains indifferent, although the EU states it has a significant interest in the strategic security situation in East Asia.

The EU points at its ‘significant stake in the maintenance of cross-Strait peace and stability’, saying it will ‘continue to take an active interest, and to make its views known to both sides’.

Policy should take account of the EU’s:

Opposition to any measure which would amount to a unilateral change of status quo;

strong opposition to the use of force;

encouragement for pragmatic solutions and confidence building measures;

support for dialogue between all parties; and,

continuing strong economic and trade links with Taiwan” (Commission 2006).

rights issues to ‘a sign of the high quality of relations between the EU and China’, but mentioned Taiwan only briefly (www.eu2006.at/de/News/Press_Releases/June/0606WinklerChina.html [ac- cessed 27.12.2006]).

The first two points can be read as an unequivocal reflection of the situation that has emerged since 2003, when Taiwan’s president Chen Shuibian presented his plans to hold a referendum as an answer to China’s deployment of missiles. The last point mentioned ex- presses the EU’s fundamental interest in sound economic relations with Taiwan. Consider- ing these points, the 2006 Communication could be regarded as progress (Bersick 2006b, Tang 2006). In 1998, for example, the EU was quite hopeful about an improvement in cross- Strait relations and did not make any demands at all. It confined itself to encouragement and the welcoming of any steps which could be taken to further the progress of peaceful reconciliation (Commission 1998).

Nevertheless, the 2006 Communication has no clear-cut message and no direct addressee.

This becomes even more obvious by looking at the bilateral talks with the PRC, one of the two possible addressees. The Joint Statement of the Ninth EU-China Summit made in Hel- sinki on 9 September 2006, for instance, only contains one sentence on Taiwan:

The EU side reaffirmed its continued adherence to ‘one China’ policy and expressed its hope for a peaceful resolution of the Taiwan question through constructive dia- logue.

This is exactly the same wording as in the previous statements made in 2005 and 2004 and virtually the same sentence as the declaration of 2003 (EU 2004, EU 2005, EU 2006, EU 2003).

Thus, it can be concluded that the treatment of the Taiwan issue during the summits repre- sents no more than a ritualized routine. This judgement is reinforced when compared with other aspects of international security that are dealt with in specific phrases (Iran’s nuclear programme, hostilities between Israel and Hezbollah, stability on the Korean Peninsula or the humanitarian situation in Darfur).

The same holds true for the preceding policy papers of the Commission. The Communica- tion of 2003 was published to make EU policy towards China more effective. The EU claimed that relations with China had expanded to cover a multitude of sectors including a robust and regular political dialogue showing a ‘new maturity’. However, we have just seen that the political dialogue on Taiwan conducted at annual summits with China is confined to set phrases – and the paper itself reflects the tone: ‘The EU has also regularly reiterated its strong interest in, and insistence on, a peaceful resolution of the Taiwan issue through dia- logue across the Taiwan Straits’. Consequently, the Commission does not consider the Tai- wan issue to be a ‘new action point’ for ‘raising the efficiency of the political dialogue’

(Commission 2003: 6, 9). The Communication contains no detailed demands, e.g. a reduction of missiles on the Chinese coast or the initiation of a dialogue without any preconditions.

Not even any (serious) concern about the deterioration of the situation in the Taiwan Strait is shown.

The neglect of the Taiwan issue in written public statements does not rule out its treatment in behind-the-scenes dialogue (Ward 2005). Quiet communication takes place on this topic, but that does not alter the fact that the EU has no audible position in this important issue for global security. Moreover, quiet communication does not necessarily imply ‘pro-Taiwan’

messages.10 The heads of almost all the EU member states as well as the EU High Represen- tative for the CFSP have visited Beijing in recent years and are known to have made efforts to establish good personal relations with the Chinese leadership (Jakobson 2004: 48).

According to Ward, there is no coherent strategy behind this kind of quiet policy, but policy priorities are shaped by perceptions. China has primarily been regarded by the EU from an economic perspective rather than a strategic one. (The same holds true for Taiwan, inciden- tally.) Secondly, there is a tendency on the part of the EU ‘to acquiesce too much to Beijing’s view’. And lastly, the EU seems to be inclined to treat the conflict as the US’s business (Ward 2005).

From the official documents we can conclude that there is no change or even modification in the principles of the EU’s China policy. It sticks to the ‘one China’ principle, hopes for a peaceful resolution of the Taiwan conflict and wants this to be done through constructive dialogue. The reiteration of this hope has constituted one essential part of its statements on the Taiwan issue for a long time. Thus, the EU shifts the entire responsibility to resolve the con- flict onto China and Taiwan. This becomes clear when we compare the wording of messages with statements on human rights. In her speech on ‘security in the Far East’, Ferrero- Waldner explained that the EU ‘made clear to China that we need improvements in the hu- man rights situation in China to create an environment conducive to a lifting’ of the em- bargo. Regarding the Taiwan issue and the Anti-Secession Law, the EU clearly expressed its concern, reiterated the principles guiding its policy, and showed it was hopeful about recent de- velopments.11

The latest and most authoritative statement of EU policy, made by the Council in its meeting on 11 and 12 December 2006 confirms this argument:

10 In a press release dated 3 February 2006 issued after the meeting of the EU Troika (Austrian For- eign Minister Ursula Plassnik, CFSP High Representative Javier Solana, Commissioner for Exter- nal Relations Benito Ferrero-Waldner) with the PRC’s Foreign Minister Li Zhaoxing, Plassnik is cited as follows: ‘The latest remarks of the Taiwanese leader Chen Shui Bian send the wrong signals for progress in mutual relations’ (3.2.2006, www.eu2006.at/de/News/Press_Releases/

February/0302TroikaChina.html [accessed 27.12.2006]).

11 Ferrero-Waldner 2005 (emphasis by G.S.).

The Council remains committed to its One China policy. The Council is convinced that stability across the Taiwan Straits is integral to the stability and prosperity of East Asia and the wider international community. The Council welcomes initiatives by both sides aimed at promoting dialogue, practical co-operation and increased confidence building, including agreement on direct cross-straits flights and reductions in barriers to trade, investment and people-to-people contacts. The Council encourages both sides to continue with such steps, to avoid provocation, and to take all possible measures to resolve differences peacefully through negotiations between all stakeholders con- cerned. The Council encourages both sides to jointly pursue pragmatic solutions re- lated to expert participation in technical work in specialised multilateral fora (Council 2006).

We must, however, concede a slight change in the comments on the state of cross-Strait rela- tions that always have constituted an integral second part of related EU statements. These comments are a function of the quality of the EU’s relations with China and a reflection of the situation in the Straits.

6.2. Slight Changes in Rhetoric

As mentioned above, the latest Communication of 2006 is seen by some researchers as a step forward. In Bersick’s view ‘it is indicative for a change (emphasis by G.S.) on the European side by spelling out the EC’s priorities in its relations with China and Taiwan’ (Bersick 2006b:11). From his analysis of the evolving wording on the official EU website since 2003, Tang concludes the development of a greater friendliness towards Taiwan and an interest of the EU in a more active involvement (Tang 2005, Tang 2006).

In fact, no substantial change can be identified (see also Laursen 2006); but, nevertheless, compared to pre-2005, Taiwan is more present in such statements. The latter is the conse- quence of an upgrading of the Council secretariat’s strategic thought on East Asia, as Laursen (2006:24) has put it. East Asia is becoming increasingly important for the EU and it has clarified its strategic interests regarding the region, especially during the UK Presidency in 2005. In 2005 and 2006 it has issued declarations

on cross-Strait direct charter flights (3 February 2005, 20 January 2006, 15 June 2006),12 on the adoption of the ‘anti-secession law’ by the Chinese parliament (14 March 2005),13 and

12 www.eu2005.lu/en/actualites/pesc/2005/02/03taiwan/index.html; www.eu2006.at/en/News/CFSP_

Statements/January/2001TaiwanChina.html; www.eu2006.at/en/News/CFSP_Statements/June/1506 TaiwanStraits.html [all accessed 27.12.2006].

on the abolishment of the National Unification Council by Taiwan’s President Chen (1 March 2006).14

In the course of issuing these statements, the EU has become more specific and detailed. The Declaration on the anti-secession law issued by the Luxembourg Presidency may serve as an example (fn 13).

The European Union asks all parties to avoid any unilateral action which might rekin- dle tensions. It would be concerned if this adoption of legislation referring to the use of non-peaceful means were to invalidate the recent signs of reconciliation between the two shores. The European Union encourages them to develop initiatives which con- tribute to dialogue and to mutual understanding in the spirit of the agreement on the direct air links established at the time of the Chinese New Year.

The European Union considers that relations between the two shores must be based on constructive dialogue and the pursuit of concrete progress, and reiterates its con- viction that this is the only approach likely to benefit both parties and to lead to a peaceful resolution of the Taiwan question.

The EU itself does, however, still refrain from proposing initiatives . Moreover, its appar- ently neutral stance becomes doubtful when we compare the critique on China and on the Taiwanese President for taking unilateral action. The Chinese leadership was only indirectly criticized for the passing of the anti-secession law:

The European Union has taken note of the adoption of an ‘anti-secession law’ by the National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China.

In this context, the European Union wishes to recall the constant principles guiding its policy, i.e. its attachment to ‘one China’ and to the peaceful resolution of disputes, which is the only means of maintaining stability in the Taiwan Straits, and its opposi- tion to any use of force.15

13 www.eu2005.lu/en/actualites/pesc/2005/03/14taiwan/index.html [accessed 27.12.2006].

14 www.eu2006.at/en/News/CFSP_Statements/March/0101TaiwanStraits.html [accessed 27.12.2006].

15 That the EU does not directly address the Chinese leadership also becomes obvious by reading the following remarks of the EU High Representative for the CFSP Solana after a meeting with the Chinese Foreign Minister Li Zhaoxing: ‘We also discussed Taiwan. You know what is the position of the European Union. I have repeated our well-known considerations on this issue. I have also expressed our concern about some elements of the anti-secession law. This law has positive ele- ments, as you know, calling for cross-Straits dialogue and co-operation – which we strongly sup- port – but also has references to potential resolution of the issue by non- peaceful means. The posi- tion of the EU is clear: first, full support to ‹one China› policy; second, the resolution of this con- flict has to be delivered through dialogue and peaceful means’ (17 March 2005, www.euro

But President Chen was directly criticized for abolishing the National Unification Council (fn 14, see also fn 10):

The EU attaches great importance to peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait. This is important to the region and beyond and the EU has on previous occasions urged both sides to refrain from actions which could increase tensions.

The EU therefore takes note with concern of the announcement by the Taiwanese leader Chen Shui-bian that the National Unification Council would cease to function and its guidelines would no longer be applied. This decision is not helpful to maintain stability and peaceful development in the Taiwan Strait.

New elements in the statements of the EU include references to the ‘status quo’ in the Straits and the support voiced for a ‘dialogue between all parties’. Both phrases, however, admit- tedly leave room for interpretation.

More improvement can be seen in non-political relations, particularly economic relations.

The EU expanded academic exchange with Taiwan (e.g., in the Erasmus programme and the 7th Framework Programme) and made Taiwan eligible for its Asia-Invest II Programme – an initiative by the European Commission to promote and support business co-operation be- tween the EU and Asia.16

7. The Paradigmatic Debate about the Arms Embargo

The EU’s debate about lifting the arms embargo on China seems to be paradigmatic for the EU’s policy towards China, or rather Taiwan, and the limited impact of enlargement. The embargo was imposed by the EU in 1989 in the wake of the brutal repression of the Tianan- men Square demonstrations, albeit without any legal precision. It is based upon a political declaration from June 1989 that simply states that EU member states will place an embargo on the ‘trade in arms’ with China. To repeal it, however, the EU member states must vote unanimously on the matter.

During separate visits to China in the autumn of 2003, the French President Jacques Chirac and the German Chancellor at that time, Gerhard Schröder, pronounced themselves in fa- vour of lifting the embargo. Their stance provoked strong opposition from the USA (Niblett 2004). In the end, despite efforts by strong advocates within the EU, including Javier Solana, parl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2004_2009/documents/fd/dcn2005042604/dcn2005042604en.pdf [accessed 27.12.2006]).

16 See http://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/projects/asia-invest/html2002/main.htm [accessed 27.12.2006].

the High Representative for CSFP, and tremendous pressure from Beijing, the embargo was not lifted.

What does this issue reveal about the EU?

- The analytical and policy-related vacuum concerning China and Taiwan allows coun- tries like France or Germany to step in and set the agenda for the EU without engaging in prior consultations with the other EU member countries. ‘Once discussions did get under way, there was no consensus on the issues at hand’, as Ward (2005) remarked.

- European debates were dominated by the implications for the bilateral relations of member states with China and not by the impact of the lifting on transatlantic relations.

The USA perceived this as strong signal that Europeans were no longer willing to sup- port its policy in the Taiwan Strait. Nevertheless, the new members were more cautious about a decision that would affect the US-EU relationship (Niblett 2004).

- The interest in the Chinese market was overwhelming. Neither did Taiwan play a central role in the European discussions until the passing of the anti-secession law. Nor did the EU seize the opportunity to connect the lifting with demands such as the ratification of the UN convention on human rights. Both Taiwan and China came to the conclusion that the EU did not harbour any serious worries about Taiwan and only changed its mind under pressure from Washington. In the course of the discussions about lifting the em- bargo, it was decided at the meeting of the EU Foreign Ministers held in January 2004 that three research reports would be commissioned, none of which included the impact that the removal of the embargo might have on Taiwan’s situation, however (Jakobson 2004: 54). In fact, the EU’s line of reasoning was exactly the opposite: in its 2006 Com- munication, the EU Commission pointed out that the improvement in cross-Strait rela- tions could improve the atmosphere for lifting economic sanctions (Commission 2006).

- Jakobson (2004: 50) concluded that Beijing ‘has been able to put pressure on the political leaders of EU countries and persuade them not to comply with Taiwan’s efforts to open up more space for itself in the international arena’ without having to cope with strong Taiwan lobbies in many of the national parliaments of the EU countries. And Beijing’s sway is likely to become more influential with its rise as a global economic and political power.

Nevertheless, the coming of the enlargement did have some impact; as it drew near, Ger- many and France were confronted with a greater pressure to act before it took effect. They expected it would be more difficult to lift the embargo in the post-enlargement situation, as many of the new EU member states are regarded as pro-Atlanticists, thus making them more susceptible to US pressure (see Jakobson 2004: 52ff.).

Opposition to lifting, however, mainly came from some of the older members, notably the Netherlands, Sweden and Denmark, who raised concerns about human rights abuses in China. Some new member states including Latvia, Poland and the Czech Republic also ex- pressed their reservations, but it seems to be very doubtful whether they were led by the same motives. Moreover, there is no evidence that the US exerted pressure on the new member states and that the Balts and the Poles were opposed to the lifting because of the strong opposition from Washington (Král 2005: 37).

Due to its enlargement, the EU now consists of a greater number of smaller member states that tend to see the embargo as the only leverage the EU has at its disposal in its dealings with China. The haste with which the larger countries had acted was deemed to have weak- ened the EU’s position at the negotiating table. Their attention, however, is directed at rela- tions with China, Taiwan’s interests do not play a significant role. That contrasts with the case of lifting diplomatic sanctions against Cuba in 2004, when there was a very strong op- position from a handful of member states, headed by the Czech Republic, who explicitly supported the Cuban democratic movement (Král 2005: 35f.).

8. Do Economic Relations with Taiwan Have Any Impact?

In its annual consultations, the EU Commission and Taiwan limit their talks to economic, commercial, cultural and scientific topics, political issues are strictly excluded. In the follow- ing, I shall discuss two questions: (a) What are the possible implications of enlargement for the EU’s trade with China and Taiwan? (b) Will economic relations stimulate the EU to play a bigger role in cross-Strait relations?

8.1. Enlargement and Sino-EU Trade

In discussing trade-creation and trade-diversion effects proceeding from EU enlargement, Zhang (2006: 4, 7f.) indicates that existing exports from a third country to the old members might be replaced by exports from the new member states and vice versa. In reality, the is- sue is more complex, as all of the trade partners interact with each other (i.e. the old and new members as well as third countries), making the situation in reality much more dy- namic. Bilateral trade disputes with China, for example, have grown in number and size as both trade and investment have expanded.

Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland are among the most important trading partners that China has in Central and Eastern Europe. These countries were China’s seventh-, thir- teenth- and eighteenth-biggest export partners, respectively (Zhang 2006: 14ff.). Moreover, a

vast number of opportunities exist for Chinese businesses in the investment field in CEECs, although China’s commercial ties with the old members are far more important. In 2006 (Jan.-Nov.) the share of EU-15 accounted for 94.2% of the total trade with the EU. The growth rate of imports and exports in trade with the new members was, however, twice as high (47%) as that with the EU-15-countries (23.9%) – compared to the same period in 2005.17 The expansion of the Common Market has provided new opportunities for Chinese busi- nesses in areas such as trade and investment. CEEC-based Chinese businesses enjoy the ad- vantages offered by the Common Market as well as the removal of tariffs and quotas. EU regulations and laws simplify market access. On the other hand, due to the relatively low costs of labour in the new member states, their exports to the old members may come to substitute Chinese exports and intra-EU trade may increase. Furthermore, China may lose out because protective trade measures against non-EU members became also effective for trade with the new members. Several WTO members have criticized this, including China and Taiwan.

8.2. Enlargement and Taiwan-EU Trade18

Up until the beginning of the 1980s, Europe remained a secondary economic partner for Taiwan. In the following decade Taiwan emerged as a major producer of electronics;

mainland China adopted its open-door policy and the Asian share of both Taiwan’s exports and imports increased dramatically. This was reflected in a declining share in trade with North America, but not in that with Europe. There, the EU and its member states have dominated trade and investment relations with the island. In 1993, exports to EU-15 ac- counted for 93.5% of Taiwan’s total exports to Europe, and they shipped 81.8% of Taiwan’s imports from Europe. Until 2000, there was no alteration in these shares; the respective fig- ures were virtually identical: 93.5% and 81.4% (Ash 2002: 162).

In 2005, Taiwan was the EU’s fifth-largest trading partner in Asia after China, Japan, South Korea and India without taking into account the share of Taiwanese companies that in- vested in China and also export to the EU.19 Trade peaked in 2000 and declined until 2002 by 22% due to international factors and Taiwan’s own economic crisis. Since 2004, it has been recovering from the downturn (table 1). Overall, the EU’s share in Taiwan’s external trade is

17 Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, http://English.mofcom.gov.cn/aarticle/

statistic/hkmacaotaiwan/200612/20061204159660.html [accessed 27.12.2006].

18 All figures are taken from EETO, ‘EU-Taiwan. Trade and Investment Factfile 2006’ (Taipei: Euro- pean Economic and Trade Office, 2006) unless cited otherwise.

19 Exports from Taiwanese-owned companies from China to the EU could amount to the same vol- ume as goods exported directly from Taiwan (ibid., 18).

diminishing because of the rapid expansion of cross-Strait trade and trade with other Asian countries.

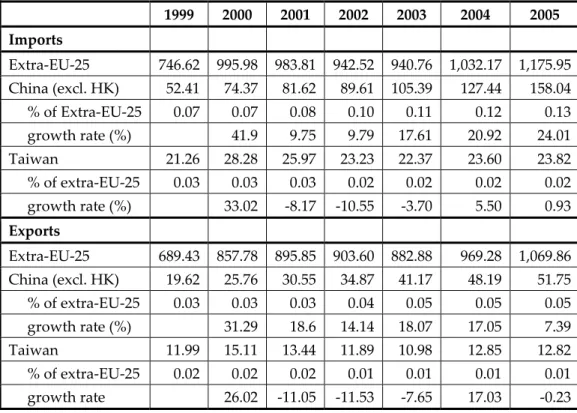

Table 1: Extra-EU-25 trade, 1999-2005 (in billion ECU/euro)

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 Imports

Extra-EU-25 746.62 995.98 983.81 942.52 940.76 1,032.17 1,175.95 China (excl. HK) 52.41 74.37 81.62 89.61 105.39 127.44 158.04 % of Extra-EU-25 0.07 0.07 0.08 0.10 0.11 0.12 0.13 growth rate (%) 41.9 9.75 9.79 17.61 20.92 24.01

Taiwan 21.26 28.28 25.97 23.23 22.37 23.60 23.82

% of extra-EU-25 0.03 0.03 0.03 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.02 growth rate (%) 33.02 -8.17 -10.55 -3.70 5.50 0.93 Exports

Extra-EU-25 689.43 857.78 895.85 903.60 882.88 969.28 1,069.86 China (excl. HK) 19.62 25.76 30.55 34.87 41.17 48.19 51.75 % of extra-EU-25 0.03 0.03 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.05 0.05 growth rate (%) 31.29 18.6 14.14 18.07 17.05 7.39

Taiwan 11.99 15.11 13.44 11.89 10.98 12.85 12.82

% of extra-EU-25 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 growth rate 26.02 -11.05 -11.53 -7.65 17.03 -0.23

Sources: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu; own calculations.

According to Taiwanese customs statistics, the overall trade in goods between the EU and Taiwan has experienced a strong growth since 2003. In 2006 (January to September) trade with the EU amounted to 9.7% of total Taiwanese trade – 10.6% of Taiwanese exports and 8.7% of imports. It grew by 6.9% (10.7% of the exports and 2.1% of the imports) relative to 2005.20

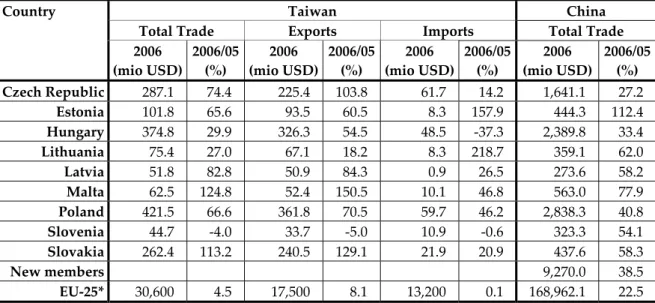

The end of the Cold War, however, did not have a significant impact on the trade pattern with Europe. Taiwan responded quite modestly to the new trade and investment opportuni- ties. Since 2004, however, the most impressive annual growth rates in bilateral trade with Taiwan have been exhibited by the new members of the EU. In 2004, trade between Taiwan and the EU-15 increased by 18.6%, trade with the ten new members increased by 20.4%. In 2005, Slovakia more than doubled its bilateral trade with Taiwan, and Hungary and Poland experienced an almost 50% increase. In 2006, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Poland and Slovakia attained growth rates of more than 50% (see table 2) (EETO 2006: 19, TROB 2005).

20 http://ekm92.trade.gov.tw/BOFT/OpenFileService [accessed 7.12.2006].

Table 2: Trade between Taiwan/China and new member states, amounts 2006/1-8 and growth rates 2006/1-8 vs. 2005/1-8

Taiwan China Total Trade Exports Imports Total Trade

Country

2006 (mio USD)

2006/05 (%)

2006 (mio USD)

2006/05 (%)

2006 (mio USD)

2006/05 (%)

2006 (mio USD)

2006/05 (%) Czech Republic 287.1 74.4 225.4 103.8 61.7 14.2 1,641.1 27.2

Estonia 101.8 65.6 93.5 60.5 8.3 157.9 444.3 112.4 Hungary 374.8 29.9 326.3 54.5 48.5 -37.3 2,389.8 33.4 Lithuania 75.4 27.0 67.1 18.2 8.3 218.7 359.1 62.0

Latvia 51.8 82.8 50.9 84.3 0.9 26.5 273.6 58.2 Malta 62.5 124.8 52.4 150.5 10.1 46.8 563.0 77.9 Poland 421.5 66.6 361.8 70.5 59.7 46.2 2,838.3 40.8 Slovenia 44.7 -4.0 33.7 -5.0 10.9 -0.6 323.3 54.1 Slovakia 262.4 113.2 240.5 129.1 21.9 20.9 437.6 58.3

New members 9,270.0 38.5

EU-25* 30,600 4.5 17,500 8.1 13,200 0.1 168,962.1 22.5 Note: * For Taiwan’s trade: 2006/1-9.

Sources: Taiwan BOFT statistics, http://ekm92.trade.gov.tw/BOFT/OpenFileService; China MOFCOM, http://Eng lish.mofcom.gov.cn/aarticle/statistic/hkmacaotaiwan/200611/20061103594132.html.

As for foreign direct investments (FDI), Taiwan is the sixteenth-biggest investor in the EU.

The island’s investments got going in the 1980s, but only since the 1990s did they become more important. Its stock of 2.2 billion euro at the end of 2002 represented only 0.2% of the total stock of FDI in the EU. In the Czech Republic and certain other countries, Taiwanese FDI is quite significant (table 3). Although the Czech statistics record investments which are only half the amount (around 400 mio USD) of those recorded by the Taiwanese, the island became the second largest investor in that country by mid-2005 (Tubilewicz 2005: 242). From the Taiwanese perspective, FDI in the EU comes to 1.5% of its total FDI. The evolution is dif- ficult to trace due to the relatively small investment amounts; investments are, however, likely to have grown since 2004.

Table 3: The main EU recipients of Taiwanese FDI, 2004

Country Taiwan FDI stock (in mio USD)

Czech Republic 870

UK 483 Italy 300 Netherlands 196

Germany 130 Hungary 90

Source: Taiwan MOEA statistics, according to EETO 2006: 28.

Compared to the growing trade with China, Taiwan is losing ground in the EU. The EU’s exports to Taiwan amount to about a quarter of its exports to China and its imports from Taiwan amount to only 15% of those from the mainland. Growth rates of imports from and exports to China are constantly higher than those from and to Taiwan. As for the new mem- bers, growth rates of trade with China are also quite impressive, but with four exceptions (Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Slovenia) consistently lower than growth rates as regards trade with Taiwan. For the period of January to September 2006 (table 2), total trade with China increased, e.g., for Czech Republic 27.2% (in comparison: with Taiwan 74.4%), Latvia 58.2% (82.8%), Poland 40.8% (66.6%), and Slovakia 58.3% (113.2%).21

The EU enlargement and the establishment of the EURO zone are seen by Ferng as factors that ‘encouraged Taiwan to accord greater priority to economic and trade relations with the EU and European countries’.22 Notwithstanding the impressive growth rates, the share of the ten new member states in EU-Taiwan trade has remained rather small and was, com- pared with Taipei’s total foreign trade as well as with its trade with the EU, hardly signifi- cant. It jumped to 5% in 2005 and to more than 7% of Taiwan’s exports to the Union (EETO 2006: 19). Therefore the relative importance of Taiwan’s economy for the CEECs is unlikely to be transformed into significant political outcomes regarding the Council and the Com- mission.

9. The CEECs’ Relations with Taiwan

The CEECs were among the first countries to establish diplomatic relations with China in 1949. Later, both sides went on to establish extensive diplomatic and commercial relations.

Although the Sino-Soviet schism in 1960 led to a freezing of bilateral contacts, it did not en- able Taiwan to gain any diplomatic ground. After the end of the Cold War, the CEECs re- established formal and informal working relations with China and followed the paths of other European nations in continuing to extend these relations. Although their primary fo- cus was on Western Europe as well as their own geographical vicinity, China has become an important political and economic partner outside Europe. After a period of ambivalence in the 1990s, the post-communist states in Central and Eastern Europe re-affirmed their strict adherence to the ‘one China’ principle. To further economic exchange with the mainland,

21 Absolute numbers cannot be compared directly due to their different sources (the Chinese MOFCOM and the Taiwanese BOFT).

22 Li-Kung Ferng: ‘Economic and trade perspectives for the EU and Taiwan under the WTO’, April 2001 (unpubl.), cited in Ash 2002: 179, fn 184.

the CEECs – similarly to the old member states – avoid sensitive issues, as the Taiwan issue continues to loom in the political background.

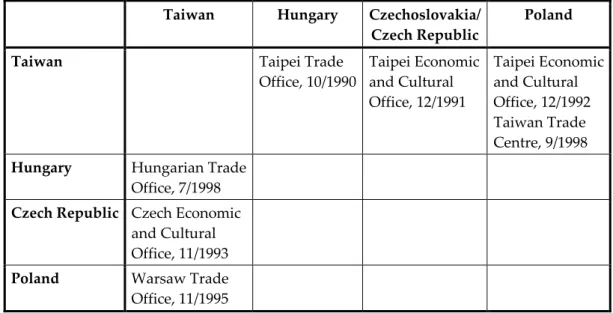

The end of the Cold War and the establishment of post-communist reform governments in the CEECs, co-occurring with the negative turn in China’s image in the wake of the June 4th suppression, created a unique opportunity for Taiwan to gain diplomatic ground by means of extending its financial support. The introduction of a market economy in Central and Eastern Europe made those countries willing to accept economic and financial aid from anywhere. Taipei’s hope, however, to attain a higher political status or even diplomatic rec- ognition by offering its economic assistance was soon to be thwarted. The new governments continued to back the ‘one China’ principle, even though some of were ready to subject it to a ‘creative’ reinterpretation. By the late 1990s, Taiwan’s achievement seemed remarkable. All Central European countries had established representative offices (see table 4), supported Taiwan’s accession to the WTO, concluded economic and cultural agreements, and provided the Taiwanese politicians with a stage for a diplomatic entrance.23 But when the Taiwanese financial promises were insufficiently kept, the Taiwanese government began to pursue a policy of quid pro quo in lieu of a ‘cash diplomacy’, and when the cost of alienating China was judged higher than the assumed benefits to be derived from supporting Taiwan, the Central European countries ‘abandoned their maverick policies on Taiwan in favour of strictly unofficial relations with the ROC’ (Tubilewicz 2005).24

Table 4: Representative Offices of Taiwan and CEECs, date of establishment, as of 1998 Taiwan Hungary Czechoslovakia/

Czech Republic

Poland

Taiwan Taipei Trade

Office, 10/1990

Taipei Economic and Cultural Office, 12/1991

Taipei Economic and Cultural Office, 12/1992 Taiwan Trade Centre, 9/1998 Hungary Hungarian Trade

Office, 7/1998 Czech Republic Czech Economic

and Cultural Office, 11/1993 Poland Warsaw Trade

Office, 11/1995

Source: Tubilewicz 2000.

23 Compare the optimistic conclusions of Tubilewicz 2000 with those of Tubilewicz 2005.

24 Tubilewicz (2000; 2005) describes this process in detail and works out the failures of Taiwan’s pol- icy very clearly.