Religion and Spirituality as a Coping Mechanism with Cancer

Volltext

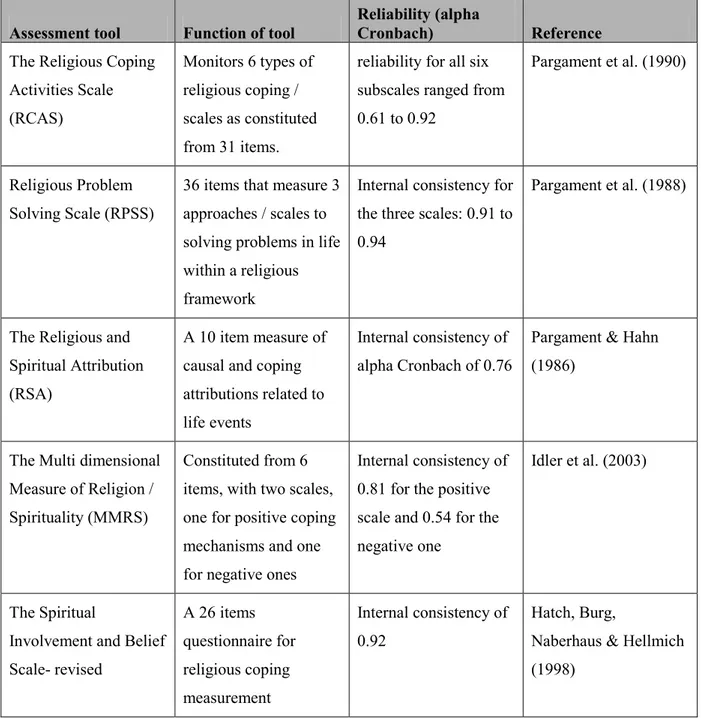

Abbildung

ÄHNLICHE DOKUMENTE

Consistent with these findings were Igf1r stainings of small intestinal and colonic tissue sections of control Villin-TRE-IGF1R mice in the present study which showed that

One does not understand why China would resume the recipes of Soviet Union, which have failed: a glacis of narrowly controlled countries and the attempt to build a “block”,

In epidemiological studies poor plasma levels of all essential antioxidants are associated with increased relative risks; in particular, low levels of carotene and vitamin E with

A comparison of immune responses to infection with virulent infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) between specific-pathogen-free chickens infected at 12 and 28 days of age.

The outcomes of Granger causality tests using VAR models indicate the presence of unidirectional causalities running from world oil price and tradable industries

While we do find evidence of some of the symptoms such as real exchange rate appreciation, the estimates aren’t robust enough to categorically attribute these

5.3 Behaviour of Cu(II) and Ni(II) Schiff base-like complexes with long, branched alkyl chains in solution and in the solid state: Micelle formation, CISSS, and

In this population-based study in a country where every- one has equal access to care, patients with newly diagnosed stage I or II breast cancer and patients with higher SES were