www.giga-hamburg.de/workingpapers

Guatemala in the 1980s:

A Genocide Turned into Ethnocide?

Anika Oettler

N° 19 March 2006

Edited by GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies / Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien.

The Working Paper Series serves to disseminate the research results of work in progress prior to publication to encourage the exchange of ideas and academic debate. An objective of the series is to get the findings out quickly, even if the presentations are less than fully pol- ished. Inclusion of a paper in the Working Paper Series does not constitute publication and should not limit publication in any other venue. Copyright remains with the authors.

When Working Papers are eventually accepted by or published in a journal or book, the cor- rect citation reference and, if possible, the corresponding link will then be included in the Working Papers website at:

www.giga-hamburg.de/workingpapers.

GIGA research unit responsible for this issue: Research Program “Violence and Security Co- operation”.

Editor of the GIGA Working Paper Series: Bert Hoffmann <hoffmann@giga-hamburg.de>

Copyright for this issue: © Anika Oettler

Editorial assistant and production: Verena Kohler

All GIGA Working Papers are available online and free of charge at the website: www.giga- hamburg.de/workingpapers. Working Papers can also be ordered in print. For production and mailing a cover fee of € 5 is charged. For orders or any requests please contact:

e-mail: workingpapers@giga-hamburg.de phone: ++49 – 40 – 42 82 55 48

GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies / Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien Neuer Jungfernstieg 21

20354 Hamburg Germany

E-mail: info@giga-hamburg.de Website: www.giga-hamburg.de

Guatemala in the 1980s:

A Genocide Turned into Ethnocide?

Abstract

While the Guatemalan Truth Commission came to the conclusion that agents of the state had committed acts of genocide in the early 1980s, fundamental questions remain. Should we indeed speak of the massacres committed between 1981 and 1983 in Guatemala as “geno- cide”, or would “ethnocide” be the more appropriate term? In addressing these questions, this paper focuses on the intentions of the perpetrators. Why did the Guatemalan military chose mass murder as the means to “solve the problem of subversion”? In Guatemala, the discourses of communist threat, racism and Pentecostal millenarism merged into the intent to destroy the Mayan population. This paper demonstrates that the initial policy of physical annihilation (genocidal option) was transformed into a policy of restructuring the socio- cultural patterns of the Guatemalan highlands (ethnocidal option).

Key words: genocide studies, Guatemala, human rights violations, massacres

This Paper was prepared for the workshop “Opting for Genocide: To What End?” in Ham- burg (organized by Hamburg Institute for Social Research), March 23-25, 2006.

Anika Oettler

is researcher at GIGA Institute for Ibero-American Studies in Hamburg. Her doctoral thesis sought to provide an analytical survey of the origins, work and effects of the Guatemalan Truth Commission and its ecclesiastical equivalent, the Catholic Project for the Recovery of Historical Memory. Her current research project concerns the Central American talk of crime.

Contact: oettler@giga-hamburg.de ⋅ Website: www.giga-hamburg.de/iik/oettler

Genozidale und ethnozidale Terrorstrategien in Guatemala

Auch wenn die guatemaltekische „Wahrheitskommission“ festgestellt hat, dass die Massa- ker in den frühen 1980er Jahren genozidale Ausmaße hatten, bleiben fundamentale Fragen umstritten: Ist der adäquate Begriff für die zwischen 1981 und 1983 begangenen Massaker tatsächlich „Genozid“ oder lassen sie sich eher als „Ethnozid“ begreifen? Um diese Fragen zu beantworten, konzentriert sich dieser Beitrag auf die Intentionen der Täter. Warum griff das guatemaltekische Militär auf Massenmord zurück, um das „Problem der Subversion“ zu lösen? In Guatemala verschmolzen antikommunistische, rassistische und millenaristische Diskurse zu einer Politik, die auf die Vernichtung der Maya-Bevölkerung zu abzielte. Im vorliegenden Beitrag wird beschrieben, wie eine genozidale Option, die auf die physische Vernichtung der Maya-Bevölkerung abzielte, zu einer ethnozidalen Option wurde: Ziel der Terrorstrategie war nunmehr die indirekte Vernichtung durch die soziokulturelle Neuord- nung des guatemaltekischen Hochlandes.

1. Introduction

2. Military Responses to Guerrilla Challenge in Guatemala 3. Structures of Violence

4. Diagnosing Genocide

5. A Closer Look at the Actors Involved 6. The Tyrant and the Preacher

7. Scientific Mass Murder

8. Conclusions: A Genocide Turned into Ethnocide

1. Introduction

Since 1948, the debate on genocide has grown in breadth and depth, but still there is no common definition. While many groups started to use the term in order to mobilize interna- tional support, scholarly reactions to persistent patterns of mass killings have been contra- dictory. For Steven T. Katz (1994), the Holocaust had been the only genocide in history. On the other hand, various scholars suggested alternative criteria for defining genocide and, thus, resolving the problem of exclusive classifications of potential victim groups. Outlining key issues in the field of genocide research, Frank Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn proposed the following definition:

“Genocide is a form of one-sided mass killing in which a state or other authority in- tends to destroy a group, as that group and membership in it are defined by the perpe- trator” (1990: 23).

The notion of the construction of the “other” has been instructive for scholars examining the process of group differentiation and stigmatization linked to genocidal acts. In her attempt to overcome the exclusiveness of victim classifications, sociologist Helen Fein noted that genocide is

“sustained purposeful action by a perpetrator to physically destroy a collectivity di- rectly or indirectly, through interdiction of the biological and social reproduction of group members, sustained regardless of the surrender or lack of threat offered by the victim” (Fein 1993: 24).

Within genocide studies, some scholars now place particular emphasis on the concept of ethnocide understood as “cultural genocide”. According to Jean-Michel Chaumont, “Ethno- cide does not primarily target individuals, but the constitutive elements of group identity”

(Chaumont 2001: 183). While Helen Fein makes no distinction between direct or indirect destruction (or: between biological and social reproduction of group members, this distinc- tion is central to Chaumont’s definition.

“Ethnocide means the intentional destruction of a group which does not necessarily imply murder or bodily harm. But an ethnocide can be genocidal, if the perpetrators believe that killing a significant part of the group’s members, e.g. the elite, is a more ef- fective form of destruction.” (Chaumont 2001: 186)

Thus, the intention is not the physical destruction of a group but the destruction of the cul- tural values that ensure cohesion, collective identity and collective action of a group. And, as

“civilization” or nationalistic re-education are often encouraged, an ethnocidal policy im- plies the possibility of individual change (Chaumont 2001: 181).

Separating genocide and ethnocide by definition seems to be of key significance for our un- derstanding of certain dynamics of genocide. If we focus on the perspective of the perpetra- tors, it is important to recognize that “massacres are the product of a joint construction of will and context, with the evolution of the latter being able to modify the former” (Semélin 2003: 202). The Guatemalan case, which received little scholarly attention, demonstrates the importance of this line of interpretation. In general, it is said

“that agents of the State of Guatemala, within the framework of counterinsurgency operations carried out, between 1981 and 1983, acts of genocide against groups of Ma- yan people who lived in the four regions analysed” (Commission for Historical Clari- fication, § 122).

In this paper, I will focus on the moment in which a policy of genocide became, from the point of view of the perpetrators, the “best solution” for the problem of insurgency. More- over, I will discuss the transformation of the policy of physical annihilation (genocidal op- tion) into a policy of restructuring the socio-cultural patterns of the Guatemalan highlands

(ethnocidal option). Due to a change of the national and international context, the initiators of the Guatemalan genocide varied their initial policy of annihilation.

2. Military Responses to Guerrilla Challenge in Guatemala

The so-called armed confrontation in Guatemala, fought between several guerrilla groups and the State, lasted for 35 years. In the early 1960s, a movement called Revolutionary Armed Forces (FAR) – founded by young nationalist military officers – came to pose the first armed challenge to the political order. After the military defeat of the FAR in the eastern parts of the country in the late 1960s, a nucleus group of survivors retreated to Mexico and the capital to regroup. In the early 1970s, new guerrilla groups emerged and moved their operations to the indigenous regions of the country. The Guerrilla Army of the Poor (EGP) began to operate in the lowland jungles of northern El Quiché, and the Organization of the People in Arms (ORPA) began to organize in the isolated mountains in the south-western coastal part of Guatemala. While the regrouped FAR concentrated its operations in the jun- gle area of El Petén, the military wing of the communist party PGT pose an armed threat to state institutions in the capital. In 1982, the four guerrilla groups merged into the Guatema- lan National Revolutionary Unit (URNG). It is important to note that the insurgent groups never had the “military potential necessary to pose an imminent threat to the State” (CEH, conclusions, § 24).

Table 1: Ethnic boundaries in Guatemala

Guatemala´s population of 12 million is considered to be divided into two prin- ciple groups: Indians and ladinos. Around 60% of the population is indigenous.

There are more than 20 separate Mayan languages spoken, being K´iche´, Mam, Q´eqchi´ and Kaqchiquel the biggest Mayan language groups. Moreover, there are small populations of Xinca and garífuna. The ladinos are defined as the non- indigenous population. The social category “ladino” does not refer to color, but to cultural identities. The ethnic dichotomy is perceived by most Guatemalans as the main ethnic boundary. Nevertheless, there is an underlying pigmentocratic system, which dominates social stratification: The ideology of blanqueamiento (“whitening”) plays an important role in social life. People recognize themselves as ladinos, Indians, Maya, whites, ladinos blancos, ladinos pardos, Europeans, mestizos, or chapines. Moreover, many Guatemalans distinguish themselves as members of specific communities or municipios.

During the first stage of the armed confrontation (1962 to 1977), insurgent and counterinsur- gent practices were concentrated in the eastern hinterland, the capital and the south coast.

Repression was selective and directed towards members of campesino and trade unions, uni- versity and school teachers, peasants and guerilla sympathizers. Nevertheless, the military began to target civilians and to implement a policy of massacres. Between 1966 and 1968, the army bombed villages in the eastern region of the country, resulting in thousands of deaths and disappearances (Ball 1999).

As the social movement got stronger and extended over the remote parts of the country, in the 1970s, repression became geographically disperse. Between 1978 and 1985, the military operations were carried out with extreme brutality, resulting in tens of thousands of deaths and over 626 massacres. Identifying indigenous communities with the insurgency, the mili- tary concentrated its operations in the western highlands (departments of El Quiché, Hue- huetenango, Chimaltenango, Alta and Baja Verapaz), the south coast and Guatemala City.

During this period, the guerilla support base and the area of insurgency expanded over the western highlands. Especially ORPA and EGP sought to gain support in indigenous com- munities. The military used this insurgent strategy to justify its repressive response. As a key part of the counterinsurgency strategy of the 1980s, the State forced large sectors of the male population to commit atrocities. It is estimated that 80% of the male population in the western highlands were organized into local paramilitary groups (Civil Defense Patrols)1. They had to keep their neighbors under surveillance, and were forced to participate in crimes such as torture, rape and massacres. „An uncontrolled armed power was created, which was able to act arbitrarily in villages, pursuing private and abusive ends.“ (CEH, con- clusions, § 51). Following the scorched earth operations, the military started to resettle the displaced population in model villages (aldeas modelos) and highly militarized villages. The military intended to integrate the indigenous population into both the fight against subver- sion and the “new Guatemalan nation”. During the peak of violence, the victims were prin- cipally indígenas and to a lesser extent ladino (non-indigenous). After 1986, the armed con- frontation continued at a lower level and repressive operations were again selective and geographically disperse. After ten years of peace negotiations, the Guatemalan government and the URNG signed the so-called Firm and Lasting Peace in December, 1996.

1 In 1996, the PACs were disbanded and their remaining 271,000 members disarmed. “On Septem- ber 13, 1996, we were demobilized because of the peace accords, and they took our weapons. Some patrulleros started to cry, because they did not want to give away their weapons.” (CEH, Vol. II: 234,

§ 1402, testimony).

3. Structures of Violence

The CEH came to the conclusion that

“The magnitude of the State’s repressive response, totally disproportionate to the mili- tary force of the insurgency, can only be understood within the framework of the country’s profound social, economic and cultural conflicts. [...] Faced with widespread political, socio-economic and cultural opposition, the State resorted to military opera- tions directed towards the physical annihilation or absolute intimidation of this oppo- sition, through a plan of repression carried out mainly by the Army and national secu- rity forces.” (CEH, Vol. V, § 24-25).

In the following paragraph I will briefly outline the structural causes, which determined the outbreak of the so-called civil war. The underlying cause of political violence is a dynamic of multiple economic, cultural and social exclusions, resulting in racist and authoritarian prac- tices. After independence in 1821, an authoritarian State evolved, serving the interests of a small – powerful and wealthy – minority (white, later ladino). Social relations in Guatemala are characterized by a long history of struggle for social inclusion and against denial of civil and political rights.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the Guatemalan State had developed a pattern of coer- cive mechanisms integrating large sectors of the indigenous population into the plantation economy (Smith 1990). While violent uprisings had characterized the relations between in- digenous communities and the state throughout the nineteenth century, indigenous resis- tance was transmuted into more evasive channels in the 20th century. In general, community relations in the western highlands remained strong

Since independence, the Guatemalan State had resorted to repression in order to maintain social control. In the western highlands, local elites built up a system of paramilitary secu- rity, fostered by impunity. In the capital, the elite maintained power structures through fraudulent elections and an extensive repressive apparatus. The creation of an anti- communist counterinsurgency state dates back to the 1950s. Following the CIA-led coup d´état in 1954, which led to the overthrow of the first democratic government in the history of the country, political spaces were closed. The framework of Cold War provided the clarity of purpose needed to restrict political participation by legal and repressive means. The U.S.

promoted repressive counterinsurgency policy within the framework of the National Secu- rity Doctrine (DSN), which defined all opponents as “internal enemies”. Thus, the militari- zation of the state began even before the first generation of the guerrilla movement emerged in the 1960s. The Catholic Church, which had supported the overthrow of president Arbenz in 1954, strongly promoted anti-communism. So did some fundamentalist protestant sects,

which felt threatened by the expansion of atheistic communism in the backyard of the United States.

It is important to note that the Catholic Church experienced fundamental doctrinal and pas- toral changes in the second half of the 20th century. The Catholic Action, that was initially started in order to “re-conquer Indian souls” (Le Bot 1995: 36), created a new generation of foreign priests, promoting social change and civil rights. Ideologically, this new generation was strongly influenced by the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) and the Episcopal Con- ference of Medellin (1968). Thousands of catechists and lay activists began to work with the excluded (Falla 2001).

During the late-1970s, social, political and cultural opposition to the established order spread throughout the country. The CEH concluded:

“In the years when the confrontation deepened (1978-1983), as the guerrilla support base and area of action expanded, Mayans as a group in several different parts of the country were identified by the Army as guerrilla allies. Occasionally this was the re- sult of the effective existence of support for the insurgent groups and of pre- insurrectional conditions in the country’s interior. However, the CEH has ascertained that, in the majority of cases, the identification of Mayan communities with the insur- gency was intentionally exaggerated by the State, which, based on traditional racist prejudices, used this identification to eliminate any present or future possibilities of the people providing help for, or joining, an insurgent project.” (CEH V, § 31)

The notion of intentional exaggeration is fundamental to the proof of genocide. But are there any statements on intentional exaggeration which can be made with fair certainty? With which intention was the threat exaggerated?

By the late-1970s, the EGP controlled significant parts of the Ixil triangle. The May 1 demon- stration in 1978 was widely perceived as a symptom of pre-insurrectional conditions. For the first time in national history, indigenous campesinos formed a contingent several blocks long. Few weeks later, the military killed 150 K´eqchi´ in response to a peaceful demonstra- tion in Panzós, Alta Verapaz. As the army’s presence was growing throughout the high- lands, large sectors of the indigenous population became radicalized and started to join the guerilla movement. A significant number of CUC members and catechists joined the Guer- illa Army of the Poor (EGP), and fewer the other guerilla organizations, ORPA, FAR and PGT. It was estimated that 250,000 to 500,000 indígenas “participated in the war in one form or another” (Arias 1990: 255). In February, 1980, two weeks after the military massacred an indigenous delegation of CUC in the Spanish Embassy, indigenous leaders produced the

“Declaration of Iximché”, which was perceived as a declaration of war. Acts of protest, resis- tance and even insurrection took place in the entire country.

“For the military and latifundistas, with their historic fears of Indian rebellion, the very fact that the Indians were being drawn into any vision of struggle was an ex- traordinary frightening prospect” (Schirmer 1998: 40).

At this point, the army opted for genocidal practices.

4. Diagnosing Genocide

Within genocide studies, the mass atrocities committed in Guatemala in the early 1980s re- ceive little attention. Of the 137 abstracts submitted for presentation at the 6th Conference of the International Association of Genocide Scholars (June 4-7, 2005), none referred to the Guatemalan experience2. Only fairly recently, research into the history and practices of genocide has also been fuelled by the Guatemalan case. Why did scholars exclude the Gua- temalan case for so long? And why do scholars now start to consider the “hitherto little- known or long-denied” (Gellately/Kiernan 2003: 8) Guatemalan genocide?

The case became relevant for genocide studies when the Guatemalan Truth Commission (“Commission for the Historical Clarification of Human Rights Violations and Acts of Vio- lence which have caused Suffering to the Guatemalan People” [CEH]) handed over its final report on February 25th 19993. The CEH estimated that 200,000 people were killed or disap- peared between 1962 and 1996.4

Based on the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, which had been ratified by Guatemala in 1949, the CEH came to the conclusion

“that agents of the State of Guatemala, within the framework of counterinsurgency operations carried out, between 1981 and 1983, acts of genocide against groups of Ma- yan people who lived in the four regions analysed”5 (CEH, § 122).

By late February 1999, Human Rights activists and scholars started to refer to the Commis- sion’s findings as the first officially sanctioned analysis of the Guatemalan genocide. While a

2 Other examples of exclusion are Chalk/Jonassohn 1990 and Jones 2004

3 For an analytical survey of the origins, work and effects of the Guatemalan Truth Commission and its ecclesiastical equivalent, the Catholic Project for the Recovery of Historical Memory, see Oettler 2004, 2006.

4 In the cases presented to the CEH, 83% of the victims were Mayan. 91% of the crimes documented by the CEH were committed between 1978 and 1984. 93% of all crimes were committed by the State and 3% by insurgent groups. Estimates for the internally displaced range from 600,000 to one-and-a-half-million. Some 150,000 refugees crossed the Mexican border.

5 The CEH had analyzed in detail the armed confrontation in four geographical regions: 1. Maya- Q’anjob’al and Maya-Chuj, in Barillas, Nentón and San Mateo Ixtatán in North Huehuetenango, 2.

Maya-Ixil, in Nebaj, Cotzal and Chajul, Quiché, 3. Maya-K’iche’, in Joyabaj, Zacualpa and Chiché, Quiché, and 4. Maya-Achi, in Rabinal, Baja Verapaz.

number of anthropologists had extensively written about the history of terror in Guatemala in the 1980s and 1990s (Carmack 1988, Falla 1992, EAFG 1997, Zur 1998), it was this notion of genocide, which led the Guatemalan case rise to some prominence in recent years6.

The CEH pointed out that acts of genocide (“actos de genocidio”) are different from policy of genocide (“política genocida”).

“There is a policy of genocide if the acts are committed with final intent (“objetivo fi- nal”) to exterminate, in part or in whole, a group. The perpetrators commit genocidal acts if the final intent is not the extermination of the group but other political, eco- nomic, military or other ends. The extermination, in part or in whole, of the group is a means to these ends.” (CEH 1999, Vol. III: 316, § 3205; own translation)

Which was the victim group?

The CEH underlined that the Accord on the Identity and Rights of Indigenous Peoples, signed as part of the peace accords in 1995, recognized Guatemala to be a multicultural na- tion. The accord defines Guatemala as being “multi-ethnic, multicultural and multilingual in nature”. Moreover, it points out that

“the indigenous peoples include the Maya people, the Garifuna people and the Xinca people, and that the Maya people consist of various socio-cultural groups having a common origin” (Accord on the Identity and Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Preamble).

Being very restricted in time and resources, the commission analyzed in detail the counter- insurgency practices in four geographical regions. The commission stated that it analyzed four ethnic groups in four regions: 1. Maya-Q’anjob’al and Maya-Chuj, in Barillas, Nentón and San Mateo Ixtatán in North Huehuetenango, 2. Maya-Ixil, in Nebaj, Cotzal and Chajul, Quiché, 3. Maya-K’iche’, in Joyabaj, Zacualpa and Chiché, Quiché, and 4. Maya-Achi, in Rabinal, Baja Verapaz. (CEH, Vol. III: 317, § 3208). Few pages later, the CEH points out that it analyzed “four ethnic groups, which are: the group maya-ixil, the group maya-achi, the group maya-kaqchikel, the group maya-q´anjob´al, the group maya-chuj and the group maya-k´iche´”. Four groups, five groups or six groups? The indigenous population, some

6 Two scholars, Victoria Sanford and Greg Grandin, made significant contributions to our under- standing of the Guatemalan case. Victoria Sanford, Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Leh- man College – CONY, worked as a consultant with the Guatemalan Forensic Anthropological Foundation and the Truth Commission. In “Buried Secrets”, she describes her work at the exhu- mation of mass graves and sheds lights on the importance of memory work. Her book, “Violencia y Genocidio en Guatemala” is based on “Buried Secrets” and the statistical evidence presented by the CEH. Recently, she made her findings available on the website of the Genocide Studies Pro- gram at the Yale Center for International and Area Studies. Gregory Grandin, Assistant Professor of History at New York University, published several books and articles on Guatemalan history and the historiographic work of truth commissions. Driven by his own experience as a contributor to the CEH report, he focused on the combination of legal and historic methods in understanding the Guatemalan genocide (Grandin 2003).

60% of the overall population of twelve million, comprises more than 22 different linguistic groups, being defined as different ethnic groups by the CEH. (The CEH merged linguistic and geographic items into one concept of ethnicity; Oettler 2004). It is important to note, however, that official politics and indigenous organizations both consider Guatemala´s population to be divided into two principal ethnic groups: the indigenous and non- indigenous (ladino) population. This division was the main starting point for the commis- sioners. Right from the beginning, Otilia Lux de Cotí, the female and indigenous member of the CEH, insisted on investigating genocidal practice and ideology. And according to the report of the Catholic Project for the Recovery of Historic Memory, which appeared in April, 1998, the Guatemalan mechanisms of terror had “certain characteristics of genocide” (OD- HAG 1998, Vol. IV: 490; own translation).

As genocide is a difficult crime to define, we have to ask, which definition of genocide was used by the CEH. The commission, headed by German Law professor Christian Tomuschat, noted that the killings committed in the early 1980s were covered by the UN Convention on Genocide.

The convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, which was adopted on December 9, 1948, stated that

“genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.“7

The commission took up the two elements of genocide incorporated into the Convention:

the intent to destroy and the acts committed.

While it was obvious that the elimination of subversion was the motive for the crimes, a genocidal policy could not be proven directly from military orders. There was some evi- dence of planned genocidal action, but not sufficient evidence. The commission presented a series of statements making genocidal intentions explicit. In 1982, Francisco Bianchi, secre- tary of de-facto president Ríos Montt, openly stated:

“The guerillas won over many Indian collaborators, therefore the Indians were sub- versive, right? And how do you fight subversion? Clearly you had to kill Indians be- cause they were collaborating with subversion.” (The New York Times, July 20, 1982, quoted in: CEH, Vol. III: 323, § 3233)

7 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Article 2.

The statements quoted in the Truth Commissions´ report are derived from military plans or manuals8, and from newspapers9. As the commissioners could not verify the extent to which these were programmatic and strategic statements, they decided to prove genocidal intent from the pattern of repressive acts. They found sufficient evidence of a systematic pattern of coordinated acts, which were committed with the intent to destroy Mayan groups.

Through an analysis of the pattern of mass atrocities in the four regions mentioned above, the CEH demonstrated that a campaign of massacres was carried out during the regimes of Lucas García and Ríos Montt. The policy of annihilation was begun by Lucas García and further systematized by Ríos Montt (Sanford 2003: 54). Identifying the local population with the guerilla, the military first sought to kill community leaders. Increasingly, entire commu- nities became target groups and massacres the cornerstone of repressive operations. The commission’s investigation revealed that a large number of children and women were direct victims of torture, rape, arbitrary execution, forced disappearance and massacres. Between 1981 and 1982, the military carried out scorched earth operations, often with helicopter sup- port, killing community leaders, raping women, massacring entire communities, burning the fields and destroying sacred places. In the Ixil region, being one of the areas most af- fected by the scorched earth operations, between 70% and 90% of all communities were de- stroyed (the number is estimated, because the total number of communities had never been registered (CEH, Vol. III: 345, § 3311). According to the CEH, the percentage of Mayan vic- tims was significantly higher than the percentage of the indigenous population in the re- gions analyzed: in the Ixil region, 97,8% of the victims were Maya (Rabinal: 98,8%, northern Huehuetenango: 99,3% and Zacualpa: 98,4%) (CEH, Vol. III: 417-418, § 3581).

It is particularly necessary to recognize, however, that the politico-military elite of Guate- mala chose mass murder to solving the problem of insurgency already in the late 1960s. The strategy of draining the water that supported the fish was first implemented when the mili- tary directed repression against civilians and entire communities in response to guerrilla operations in the eastern parts of the country. But it was not until the 1980s that the military began its infamous scorched earth policy in the western highlands. “The imperatives of war, both civil and class, accelerated nationalism, anticommunism, and racism into a murderous fusion” (Grandin 2005, § 31).

8 Plan Nacional de Seguridad y Desarrollo, 1982 (Ejército), Manual de guerra contrasubversiva, 1982 (Centro de Estudios Militares), Manual de Inteligencia G-2, 1972 (Centro de Estudios Militares), Plan de campaña Victoria 1982 (Ejército).

9 NYT, El Imparcial, Foreign Broadcast Information Service.

5. A Closer Look at the Actors Involved

A closer look at the corporate entities and high ranking military officers planning and im- plementing counterinsurgency operations in the 1970s and 1980s reveals that the atrocities committed throughout the western highlands were a scientific means. Guatemalan military officers were utterly convinced that they were facing a permanent internal war, and a per- manent struggle over hearts and minds. Their mission was the total extermination of sub- version or communism.

“[...] it was murder with a scientific purpose and philosophy, not random carnage for its own sake. Benedicto Lucas García had learned his tradecraft at France´s famous St.

Cyr military academy, and had seen it put to good effect in the counterinsurgency war in Algeria. Rios Montt had learned his under US instructors, and had been part of the military generation that saw it work in Guatemala in the brutal successes of the late 1960s.” (Black 1984: 135)

In Latin America, the reign of the National Security Doctrine began with the Brazilian coup d´état in 1965. The DNS bore enormous political influence, since it legitimized all atrocities committed in order to cut the communist cancer out of the nation’s body. Labeling commu- nism a cancer, military strategists throughout the Western hemisphere invited extermination of the “subversive other”. The demonization of all opponents modified the consciousness of local perpetrators and the public, so that people became indifferent to human suffering.

Fighting against the spreading cancer of communism implied a dehumanizing effort in or- der to justify the extermination of potential victims. In general, the National Security Doc- trine perceived the military as the last bulwark against moral decay. As Argentine Captain Horacio Mayorga stated:

“Ours is a healthy institution. It is not contaminated by the ulcer of extremism, nor by a Third World adulteration which does not recognize the true Christ, nor by the tortu- ous and demagogic attitudes of hypocritical politicians who adopt an attitude one day and forget it the next.” (quoted in: CONADEP 1984: Part V: The Doctrine behind re- pression)

Above all, it is necessary to recognize that the National Security Doctrine went beyond tradi- tional repressive strategies. The prototypical version of DNS was produced by Brazilian General Golbery do Couto e Silva, who was particularly influential in the formation of the Advanced War College of Brazil, which was responsible for national security studies. Em- phasizing the threat of internal subversion, he stressed the significance of economic devel- opment and, thus, the national integrity. In his view,

“it was therefore vitally important to develop the country’s vast uninhabited expanses, which he categorized as ‘paths of penetration’, and it would be eventually desirable ‘to flood the Amazon region with civilization’” (Smith 2000: 203).

In Latin America, development programs and psychological warfare served as fundamental pillars of counterinsurgency strategies.

It is not surprising, then, that the Guatemalan counterinsurgency strategies were guided by external advice. The U.S. Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) used its military installations in Panama as the nerve center for its influence on Latin American politics. From 1946 to 1984, thousands of Latin American soldiers received training in military and counterinsurgency practices (in 1984, the School of the Americas was transferred to Fort Benning, Georgia). U.S.

intelligence officers were cornerstones of a hemispheric network, which involved Guatema- lan as well as other Latin American militaries. A list of high-ranking Guatemalan militaries prepared by the NGO National Security Archive (2000) shows the great influence of the School of the Americas and other military schools (Inter-American Defense College10, mili- tary schools in the United States, Venezuela, El Salvador, Argentina, Mexico and France).

Efraín Ríos Montt was trained at the School of the Americas in 1950, at Fort Bragg in 1961, in Italy in 1962, and at the Inter-American Defense College in 1973. His successor, Oscar Hum- berto Mejía Víctores, received military training at the Inter-American Air Force Academy in 1955, at Andrews Air Force Base (Maryland) in 1957, and at the Escuela Militar México from 1966 to 1969.

Whilst the National Security Doctrine received firm support from military actors throughout the continent, in Guatemala, it was to merge with racist attitudes into a genocidal fusion.

And it is important to note that the U.S. government was fully aware of the repressive tactics being used by the Guatemalan military. In 1981, Jeane J. Kirkpatrick, Ronald Reagan´s am- bassador to the United Nations, stated that “Central America is the most important place in the world for the United States today” (Smith 2000: 182). Thus, Central America was identi- fied as a fundamental battleground of the war against communism. The Reagan administra- tion devoted unequivocal support to the Salvadorean and Guatemalan governments in their fight against the subversive threat. Openly denouncing the communist takeover of Nicara- gua and the destabilizing tendencies in El Salvador and Guatemala, the US-state department opted for a wait-and-see-attitude:

10 According to its website (2006), the Inter-American Defense College “is an international educa- tional institution operating under the aegis and funding of the OAS and the Inter-American De- fense Board. It provides a professionally oriented, multidisciplinary, graduate-level course of study. This eleven-month program provides senior military and government officials with a com- prehensive understanding of governmental systems, the current international environment, struc- ture and function of the Inter-American system, and an opportunity to study broad based security issues affecting the Hemisphere and the world. The development of these concentrations is ac- complished through the detailed study of political, economic, psychosocial, and military factors of power.” (www.jid.org/en/college/).

“Recent history is replete with examples where repression has been “successful” in exorcising guerrilla threats to a regime’s survival. Argentina and Uruguay are both re- cent examples which come to mind.” (US Department of State, Secret memorandum:

Guatemala: What Next?, 1981)

6. The Tyrant and the Preacher

The political projects of the generals, who came to power in the late 1970s and early 1980s, hint at the configuration of society and the leadership of certain power blocs.

In the 1970s, Guatemala was ruled by three generals: Carlos Arana Osorio (1970-1974), Kjell Laugerud García (1974-1978), and Romeo Lucas García (1978-1982). During this period, the military became a strong political force, being engaged in key economic sectors such as fi- nance (e.g. Army Bank) and agro-exporting. The government sold hundreds of land titles to high-ranking military officers in the Franja Transversal del Norte – the agrarian frontier in the northern lowlands. Corruption has always been endemic to Guatemalan society, but during this period, it became more pervasive and blatant than ever.

Fernando Romeo Lucas García, who assumed presidency in 1978, was born in Alta Verapaz in 1924. In 1945, he started his military career as a cadet at the Escuela Politécnica. Between 1960 and 1965, Lucas García, who spoke Keqchi´ fluently and who owned large estates in Alta Verapaz, was a Member of Congress. In the late 1960s, he served as a Oficial de Opera- ciones (S3) at the Zona Militar Zacapa. By 1973, he had risen to the rank of a brigadier gen- eral. He belonged to the faction of anticommunist hardliners, which dominated national politics in the late 1970s. In the fraudulent 1978 presidential elections, he was supported by the army leadership and his predecessor, General Kjell Eugenio Laugerud García. During his presidency, he purchased large farms in the Franja Transversal del Norte. Under his re- gime, massive repression mounted and expanded throughout the country. State-sponsored death squads started a frontal attack on the social movement, leaving dozens of bodies every day on the streets. Right-wing death squads targeted all opponents, and carried out acts of

“social cleansing”. It is important to note that many killings had local origins (Carmack 1988: 53-54), and that many local landowners, labor contractors or politicians were involved in death-squad activity (CEH 1999, Vol. II: 112, § 1085; CEH 1999, Vol. II: 120, § 1109). As part of the government’s development plan for the Franja Transversal del Norte, the Instituto Nacional de Electrificación (INDE) intended to build the Chixoy dam in the Maya Achì region of Alta and Baja Verapaz. Following the community of Río Negro’s refusal to resettle, an intimidation campaign against the local population began (EAFG 1997, chapter 1.3.). In March, 1982, the military, together with 15 patrulleros of Xoxoc, carried out a massacre, kill-

ing 70 women and 117 children (CEH 1999, caso ilustrativo N° 19). Between 1980 and 1982, an estimated 427 of the 700 inhabitants of the village were assassinated. Some of the worst massacres were committed in the last months of the Lucas regime, In Seguachil (Chisec, Alta Verapaz), at least 47 villagers were killed in November, 1981 (CEH, ci N° 2). In Cuarto Pueblo (Ixcán), 400 people were assassinated between 1981 and 1982 (CEH, ci N° 4). In Feb- ruary, 1982, the military committed a massacre in Paquix (Sacapulas, Quiché), in which 58 civilians died (CEH, ci N° 39). In general, “these years are remembered as one of the darkest chapters in Guatemalan history: la época de Lucas.” (ODHAG 1998, Vol. III: 90; own transla- tion). Lucas García was perceived as a “psychotic tyrant” (Black 1984: 26) by the population.

When indiscriminate repression proved to be ineffective and discontent among the eco- nomic elite grew, Lucas García was deposed by a coup d´état. In March, 1982, a three- member military junta assumed power. It involved Lucas García´s friends General Horacio Maldonado Schaad and Colonel Luis Gordillo Martínez, and born-again Pentecostal General Efraín Ríos Montt. The latter was born in Huehuetenango (western highlands) in 1926, and started his military career at age sixteen. As many high-ranking officers, he taught at the Escuela Politécnica, and studied counterinsurgency strategies at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

In 1974, he had been the candidate of the United National Opposition (UNO) led by the Christian Democratic Party. After he had been blatantly defrauded of electoral victory, he went to “diplomatic exile”. When he returned from Spain in 1977, he joined the World Church, El Verbo. “Charismatic religion became a balm for his wounds, transfigured his ambitions, and offered to realize them in the Lord´s way” (Stoll 1988: 95-96). Gospel Out- reach/World Church/El Verbo was founded in Eureka, California, in the early 1970s: Lay preacher Jim Durkin acquired the Lighthouse ranch commune and taught a group of hippie followers about the millennial drama and the Second Coming of Christ (Stoll 1988: 92-93). In the early 1980s, 4,000 people were said to belong to Gospel Outreach, having forty congrega- tions in the United States – and one in Guatemala. Following the earthquake in 1976, Gospel Outreach and its moral rigidism attracted many followers, especially among the upper classes (Garrard-Burnett 1998: 139).

At first, Ríos Montt’s rule was marked by his embrace of El Verbo. He appointed two mem- bers of the World Church to ad-hoc created advisory positions, and appeared on Pat Robert- son’s talk show The 700 Club. Moreover, he addressed the Guatemalan public every Sunday in a series of television and radio broadcasts. The speeches, widely known as “sermons”, outlined his plan to create a New Guatemala (La Nueva Guatemala), based on three funda- mental principles: Morality, discipline and order, and national unity (Garrard-Burnett 1998: 141). Realizing the need for moral credibility, Ríos Montt immediately initiated a plan to end the widespread corruption in the military and the public administration.

For Ríos Montt,

“communism represented the ultimate rejection of morality and God-given authority;

it had to be countermanded by his own divinely sanctioned ‘final battle against sub- version’, which he conceptualized in nearly apocalyptic terms” (Garrard-Burnett 1998: 145).

Moreover, he designed repressive tactics as an accompaniment to his social engineering pro- ject. Ríos Montt, who intended to rescue the Indian souls, sought to integrate all Guatema- lans into his New Guatemala. Thus, he “mayanized” both state institutions and the counter- insurgency apparatus. For instance, he established a Council of State (Concejo de Estado), replacing the National Assembly. The 34 Council members included ten indígena representa- tives (Schirmer 1998: 28). A second example is the Special counterinsurgency units, the Fuer- zas de Tarea, which were established throughout the armed confrontation to carry out coun- terinsurgency operations. In the early 1980s, the army established the Fuerza de Tarea Gu- marcaj, which operated in the highlands of El Quiché and Huehuetenango. After the mili- tary coup d´état against Lucas García, a young Maya-quiché commander, who had been a member of EMP, was appointed commander of this unit (ODHAG 1998, Vol. II: 102). Most of these task forces participating in the genocidal campaign were given Mayan names: e.g.

Iximché, Kaibil Balam, Quetzal, and Tigre. Obviously, these appropriations of indigenous cultures were both terror instruments and paternalistic attempts to create a “multicultural”

national identity.

Although his moral fervor seemed to be highly overdone, the institutionalist faction within the military supported Ríos Montt, who was believed to be able to fight both corruption and communism (Black 1984: 127-128). During the 1970s, there had been two opposing factions within the military: a group of anticommunist hardliners, who believed in the effectiveness of brute military force; and a faction of institutionalist officers, who preferred the combina- tion of military operations and national development programs. When the insurgent move- ment extended into sixteen of the twenty-two departementos of the country in the early 1980s, the strategy of indiscriminate terror proved to be ineffective. It became obvious that massive repression alone did not meet its objective of eliminating the subversive threat. Thus, the institutionalist faction gained power and started to implement its 30/70% strategy after the 1982 coup d´état.

“So we had 70 percent Beans and 30 percent Bullets [as our strategy in 1982]. That is, rather than killing 100 percent, we provided food for 70 percent. Before, you see, the doctrine was 100 percent, we killed 100 percent before this.” (General Héctor Gramajo, interview, quoted in: Schirmer 1998: 35)

7. Scientific Mass Murder

After the March 1982 coup d´état, three military officers (Colonel Rodolfo Lobos Zamora, Colonel César Augusto Cáceres Rojas, Colonel Héctor Gramajo Mortales), together with some economists from SEGEPLAN, created the National Plan of Security and Development (Schirmer 1998: 22-23). The three men had started their careers in the late 1950s, and they shared some military experiences and world views. Moreover, at certain stages in their mili- tary careers, all of them had studied counterinsurgency strategies at military academies abroad.11 The purpose of their National Plan of Security and Development was not only to determine the departments considered “Areas of Conflict”, but to establish a long term poli- tico-military strategy. The Plan was premised on the fact that the traditional terror had proven to be ineffective. Thus, the war had to be fought on political, economic and social fronts. Especially, the military had to implement a policy of psychological warfare in order to conquer the minds of the people. According to the three colonels, fundamental social goals of the military regime were:

“To achieve the reconciliation of the Guatemalan family in order to favor national peace and harmony […] To recover individual and national dignity […] To establish a nationalistic spirit and to lay the foundations for the participation and integration of the different ethnic groups which make up our nationality.” (quoted in: Schirmer 1998: 284-285)

The Plan, which combined repressive strategies and development programs, was centered around five successive plans. In the view of the authors, each year plan dealt with all aspects of counterinsurgency, but shifting from National Security to National Stability:

- As mentioned above, the principal mission of Victoria 82 (or: Operation Ashes: Oper- ación Ceniza) was to eliminate subversion in the main “Areas of conflict”. The mili- tary intended to restore control by undertaking scorched earth operations. Thus, communities were classified on a map by colored pin, and especially the “red” com- munities, classified as being in the hands of the guerilla, were chosen as a target.

- Firmeza 83 (Firmness) focused on the establishment and extension of Civil Defense Patrols. On the other hand, it established the Plan of Assistance to Conflict Areas (PAAC), which recruited surviving indígenas for intelligence purposes and the con- struction of roads and refugee villages. The motto, “Techo, Trabajo y Tortilla” (Shel-

11 Héctor Alejandro Gramajo Morales: United States Army Infantry School (1959, 1966, 1969), School of the Americas (1967), Inter-American Defense College (1975-1976); Rodolfo Lobos Zamora:

United States Army Infantry School (1959), Escuela Militar, Colombia (1965); César Augusto Cáceres Roja: Military Academy, France (1959), Inter-American Defense College (1981).

ter, Work, and Bread) is believed to have a El Verbo origin (Harris Whitbeck or Alvaro Contreras Valladares are both said to be the creators, see Schirmer 1998: 302).

- The next stage, Re-Encuentro Institucional 84 (Institutional Re-Encounter) did not only prepare the return to democracy (Constituent Assembly Elections, July 1984), but es- tablished Polos de Desarollo (Poles of Development) and Aldeas Modelos (Model Vil- lages). There were four large Poles of Development in the postmassacre areas: the Ixil Triangle, Chisec (Alta Verapaz), Chacaj (Huehuetenango), Playa Grande (lowlands of northern Quiché). Within these Poles, some 50 Model Villages were planned to be built. A Model Village is best understood as a Panopticon, an “enclosed, segmented space, observed at every point” (Foucault 1995: 196). In contrast to their tradition of dispersed settlement, the displaced were resettled in concentrated villages. The spa- tial reorganization was designed to change Indian identity and, thus, to destroy co- hesion and collective action in indigenous communities (CEH 1999, Vol. 3: 239,

§ 3028) Villagers were forced to abandon traditional cultural patterns in favor of “na- tional” ones. The military replaced traditional Mayan authorities by PAC command- ers. In general, Model Villages were designed to re-educate the indigenous popula- tion. As part of the imagined Guatemalan nation, the “Sanctioned Mayan” was to be created as a Spanish-speaking citizen emptied of history (Schirmer 1998: 113-117).

- The mission of Estabilidad Nacional 85 (National Stability) was to intensify and further expand military operations and development programs throughout the country, and to hold presidential elections.

- During Avance 86 (Advance), a civilian was to assume presidency.

In general, the three colonels established a concept of integrating security and development.

While the first phase focused on the elimination of the guerrilla and of its civilian support base, subsequent stages of the plan moved away from genocidal strategies. As mentioned above, there was significant external influence on military planning – and on the shift from physical elimination to re-education and psychological warfare. Argentine, Israeli, Taiwan- ese and U.S. advisors are said to have had a strong influence (Schirmer 1998: 59, Black 1984: 134).

8. Conclusions: A Genocide Turned into Ethnocide

In marked contrast to the época de Lucas, the Ríos Montt regime had empowered a faction within the military, that emphasized scientific counterinsurgency strategies based on psy- chological warfare and development programs. Despite many similarities between the Gua-

temalan counterinsurgency strategy and other Latin American National Security Doctrines, the Guatemalan concept differed in one fundamental respect: It included a systematized scorched earth policy. But, would this intention be called genocide?

In the Guatemalan case, it is not sufficient only to focus on the pattern of mass atrocities committed in Guatemala in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but rather to take into account the point of view of the perpetrators. As outlined above, the Guatemalan military started to im- plement a policy of massacres in the late 1960s. These terror tactics were deployed by the military as an operation of prevention of communist takeover. In 1978, anthropologist Robert M. Carmack wrote in his diary:

“Revolution is at the door; people are so tired of problems that none will defend the government. Only the army defends, and it has become a privileged elite, selfish and unpopular.” (Carmack 1988: 44)

Again, the rhetoric of subversive threat served to justify the carnage committed by military units and right-wing death squads in the western highlands. But in contrast to the 1960s, counterinsurgency operations targeted the indigenous population. The discourse of the en- emy to be destroyed was now fed by racist prejudices and the fear of Indian retaliation.

Thus, the fundamental stereotype of the enemy was “the figure of the suspect, of a two- faced other” (Semélin 2003: 197). The Indian was believed to have a secret and dangerous side, which was to become manifest one day. As the guerrilla started to control remote areas of the country, the military and local elites saw retaliation drawing near. At this point, an influential faction of the military realized that indiscriminate terror made the insurgent movement even stronger. Thus, the policy of physical annihilation was transformed into a policy, which combined murder and the destruction of the cultural identity of the enemy.

Under the regime of Efraín Ríos Montt, the option of “genocidal ethnocide” (Chaumont 2001: 186) dominated counterinsurgency strategies. The discourses of anti-communism, ra- cism and Pentecostal millenarism had merged into a vision of ethnic engineering.

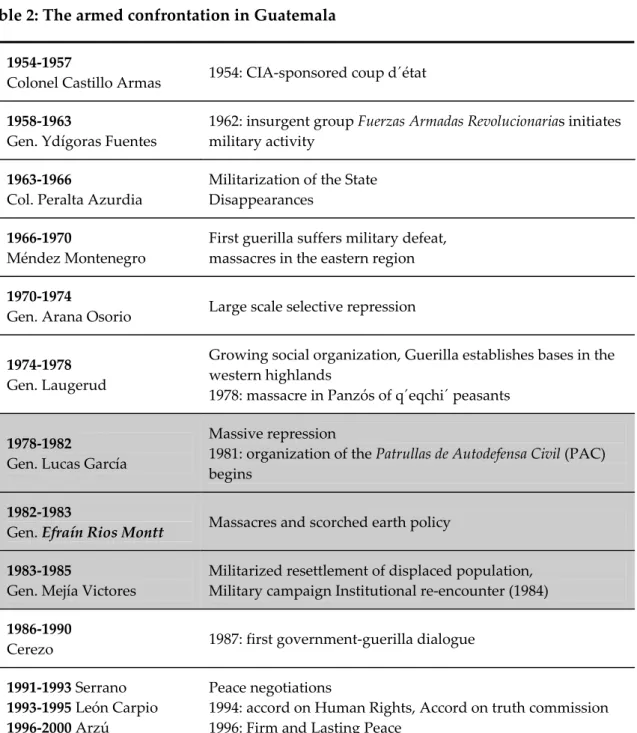

Table 2: The armed confrontation in Guatemala 1954-1957

Colonel Castillo Armas 1954: CIA-sponsored coup d´état

1958-1963

Gen. Ydígoras Fuentes

1962: insurgent group Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias initiates military activity

1963-1966

Col. Peralta Azurdia

Militarization of the State Disappearances

1966-1970

Méndez Montenegro

First guerilla suffers military defeat, massacres in the eastern region

1970-1974

Gen. Arana Osorio Large scale selective repression

1974-1978 Gen. Laugerud

Growing social organization, Guerilla establishes bases in the western highlands

1978: massacre in Panzós of q´eqchi´ peasants

1978-1982

Gen. Lucas García

Massive repression

1981: organization of the Patrullas de Autodefensa Civil (PAC) begins

1982-1983

Gen. Efraín Rios Montt Massacres and scorched earth policy

1983-1985

Gen. Mejía Victores

Militarized resettlement of displaced population, Military campaign Institutional re-encounter (1984)

1986-1990

Cerezo 1987: first government-guerilla dialogue

1991-1993 Serrano 1993-1995 León Carpio 1996-2000 Arzú

Peace negotiations

1994: accord on Human Rights, Accord on truth commission 1996: Firm and Lasting Peace

References

Adams, Richard N. (1988): What Can We Know About the Harvest of Violence?, in: Car- mack, Robert M. (ed.), Harvest of Violence. The Maya Indians and the Guatemalan Cri- sis, Norman/London: University of Oklahoma Press, pp. 274-292.

--- (1990): Changing Indian Identity: Guatemala’s Violent Transition to Modernity, in:

Smith, Carol A. (1990), Guatemalan Indians and the State 1540 to 1988, Austin: Univer- sity of Texas Press, pp. 230-257.

Ball, Patrick; Kobrak, Paul; Spirer, Herbert F. (1999): State Violence in Guatemala, 1960-1996:

A Quantitative Reflection. Washington, D.C.

Baumann, Zygmunt (1989): Modernity and the Holocaust. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Black, George (1984): Garrison Guatemala. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Carmack, Robert M. (ed.) (1988): Harvest of Violence. The Maya Indians and the Guatema- lan Crisis. Norman/London: University of Oklahoma Press.

Chalk, Frank; Jonassohn, Kurt (1990): The History and Sociology of Genocide: Analyses and Case Studies. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Chaumont, Jean-Michel (2001): Die Konkurrenz der Opfer. Lüneburg.

Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico (CEH) (1999): Guatemala, memoria del silencio, 12 tomos. Guatemala.

Commission for Historical Clarification: Guatemala. Memory of Silence. Conclusions and Recommendations. Online Report, in:

http://shr.aaas.org/guatemala/ceh/report/english/toc.html (visited: August 4, 2003, Feb- ruary 20, 2006).

CONADEP (National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons) (1984): Nunca más!

Never Again! Online Report, in: www.nuncamas.org/english/library/nevagain/ (visited:

February 20, 2006).

Equipo de Antropología Forense de Guatemala (1997): Las masacres en Rabinal. Guatemala:

EAFG.

Falla, Ricardo (1992): Masacres de la selva, Ixcán,Guatemala (1975-1982). Guatemala: USAC Editorial Universitaria.

Fein, Helen (1993): Genocide: A Sociological Perspective. London et al.: Sage.

Foucault, Michel (1995): Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison. NY: Vintage Books.

Garrard-Burnett, Virginia (1998): Protestantism in Guatemala. Living in the New Jerusalem.

Austin: University of Texas Press.

Gill, Lesley (2004): The School of the Americas: Military Training and Political Violence.

Duke University Press.

Grandin, Greg (2000): Chronicles of a Guatemalan Genocide Foretold, in: Nepantla: Views from South, 1:2, pp. 391-412.

--- (2005): The Instruction of Great Catastrophe: Truth Commissions, National History, and State Formation in Argentina, Chile, and Guatemala, in: American Historical Review, 110:1, pp. 46-67.

Jones, Adam (ed.) (2004): Genocide, War Crimes & the West: History and Complicity. Lon- don: Zed Books.

National Security Archive (2000): National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 32, The Guatemalan Military: What the U.S. Files Reveal, Volume I: Units and Officers of the Guatemalan Army, in: www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB32/vol1.html.

Oettler, Anika (2004): Erinnerungsarbeit und Vergangenheitspolitik in Guatemala. Schriften- reihe des IIK; Band 60, Frankfurt/M: Vervuert.

---: Encounters with History. Dealing with the Present Past in Guatemala, in: European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, forthcoming.

Oficina de Derechos Humanos del Arzobispado de Guatemala (ODHAG) (1998): Guatemala:

Nunca Más. 3 Vol., Guatemala: ODHAG.

Sanford, Victoria (2003): Buried Secrets: Truth and Human Rights in Guatemala. New York:

Palgrave Macmillian.

--- (2004): Violencia y Genocidio en Guatemala. Guatemala: F&G Editores.

Schirmer, Jennifer (1998): The Guatemalan Military Project. A Violence called Democracy.

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Semélin, Jaques (2003): Toward a vocabulary of massacre and genocide, in: Journal of Geno- cide Research, 5 (2003) 2, pp. 193-210.

Smith, Carol A. (1990): Guatemalan Indians and the State 1540 to 1988. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Smith, Peter H. (2000): Talons of the Eagle. Dynamics of U.S.-Latin American Relations. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stoll, David (1988): Evangelicals, Guerrillas, and the Army: The Ixil Triangle under Ríos Montt, in: Carmack, Robert M. (ed.), Harvest of Violence. The Maya Indians and the Guatemalan Crisis, Norman/London: University of Oklahoma Press, pp. 90-118.

US Department of State (1981): Guatemala: What Next? October 5, 1981, Secret memoran- dum, in: www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB11/docs/13-01.htm.

Zur, Judith N. (1998): Violent Memories. Mayan War Widows in Guatemala. Boulder.

GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies / Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien Neuer Jungfernstieg 21 • 20354 Hamburg • Germany

e-mail: info@giga-hamburg.de • website: www.giga-hamburg.de

Recent issues:

No 18 Heike Holbig: Ideological Reform and Political Legitimacy in China: Challenges in the Post-Jiang Era; March 2006

No 17 Howard Loewen: Towards a Dynamic Model of the Interplay Between International Institutions; February 2006

No 16 Gero Erdmann and Ulf Engel: Neopatrimonialism Revisited − Beyond a Catch-All Concept; February 2006

No 15 Thomas Kern: Modernisierung und Demokratisierung: Das Erklärungspotenzial neuer differenzierungstheoretischer Ansätze am Fallbeispiel Südkoreas [Modernization and Democratization: The Explanatory Potential of New Differentiation Theoretical Approaches on the Case of South Korea]; January 2006

No 14 Karsten Giese: Challenging Party Hegemony: Identity Work in China’s Emerging Virreal Places; January 2006

No 13 Daniel Flemes: Creating a Regional Security Community in Southern Latin America: The Institutionalisation of the Regional Defence and Security Policies; December 2005

No 12 Patrick Köllner and Ma�hias Basedau: Factionalism in Political Parties: An Analytical Framework for Comparative Studies; December 2005

No 11 Detlef Nolte and Francisco Sánchez: Representing Different Constituencies:

Electoral Rules in Bicameral Systems in Latin America and Their Impact on Political Representation; November 2005

No 10 Joachim Betz: Die Institutionalisierung von Parteien und die Konsolidierung des Parteiensystems in Indien. Kriterien, Befund und Ursachen dauerha�er Defizite [The Institutionalisation of Parties and the Consolidation of the Party System in India. Criteria, State and Causes of Persistent Defects]; October 2005

No 9 Dirk Nabers: Culture and Collective Action – Japan, Germany and the United States a�er September 11, 2001; September 2005

No 8 Patrick Köllner: The LDP at 50: The Rise, Power Resources, and Perspectives of Japan’s Dominant Party; September 2005

No 7 Wolfgang Hein and Lars Kohlmorgen: Global Health Governance: Conflicts on Global Social Rights; August 2005

No 6 Patrick Köllner: Formale und informelle Politik aus institutioneller Perspektive: Ein Analyseansatz für die vergleichenden Area Studies [Formal and Informal Politics from an Institutional Perspective: An Analytical Approach for Comparative Area Studies]; August 2005 All GIGA Working Papers are available as pdf files free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/

workingpapers. For any requests please contact: workingpapers@giga-hamburg.de.

Editor of the Working Paper Series: Bert Hoffmann.