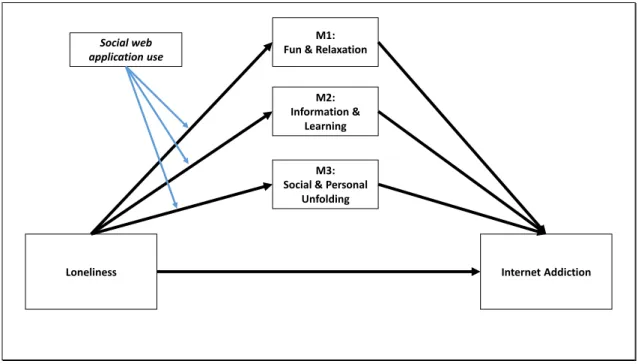

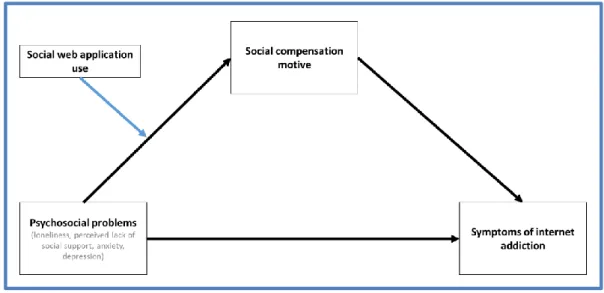

The use of social web applications as a functional alterna- tive in loneliness coping: investigating the plausibility of a model of compensatory Internet use

Volltext

Abbildung

ÄHNLICHE DOKUMENTE

The number of Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) driven applications to control actual devices is rapidly increasing, ranging from robotic arms to mobile platforms.. However, each

Note that no parameter has such effects that changes in a single parameter diminishes the gap between the test data set and the real data set with respect to

The main aim of the 'System for Analyzing Mathematical Flow Models' ( F'KA system ) described in this paper is to supply the decision-maker with a computerized tool

ABSTRACT: This paper connects the Political Opportunity Structure Theory with scholarly advances on social movements’ behavior on the Internet in order to understand the impact of the

The significance of achieving undetectable MRD earlier versus later in disease course (i.e. For patients eligible to transplant, MRD testing should be done at two 98. timepoints:

Development of a mathematical model of a water resources system and simulation of its operation over a long trace of synthetic inflows (simulation coupled with a

In classical credibility theory, we make a linearized Bayesian forecast of the next observation of a particular individual risk, using his experience data and the statis- tics

Regulatory miRNAs (e.g., miR-223) are expressed in neutrophils and transfer from neutrophils to pulmonary epithelial cells to dampen acute lung injury [209]. This indicates that