SUBJECTIVE MORALITY – EMPIRICAL STUDIES ON HOW PEOPLE BALANCE THEIR OWN INTERESTS WITH THE INTERESTS OF OTHERS AND EXPERIENCE MORAL MEANING

Volltext

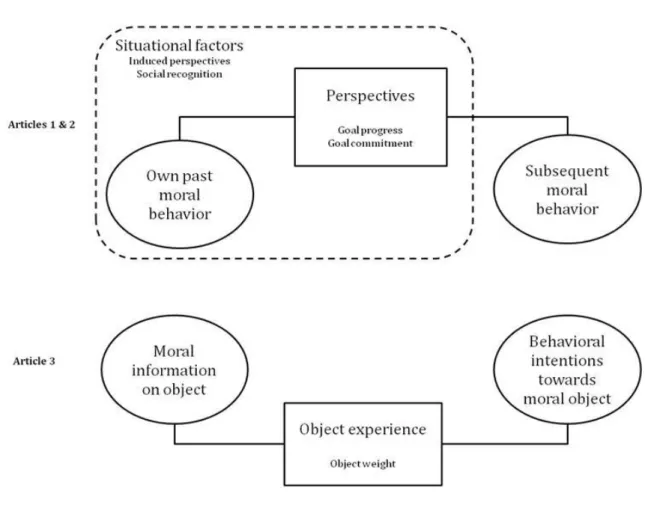

Abbildung

ÄHNLICHE DOKUMENTE

Based on interviews with 25 business leaders, 4 moral identity statuses were identified: achievement (commitment to a personally meaningful moral value framework that had

The dispositional view advanced above explains why it is plausible to think that evidence responsiveness is constitutive of belief while this does not warrant think- ing that

1) Die definierte Zielgruppe der 20 bis 35-Jährigen zeigt Interesse an der CSR- Thematik und nimmt Informationen über das gesellschaftliche Engagement von Unternehmen

ur kundliche Nachweis über die Anfertigung einer Klinge stammt aus dem Jahr 1363. Zwei Gründe sind hervorzuheben, wenn es um die Frage geht, warum sich gerade

Man beginnt zu fühlen, daß die angehäuften Materialmassen im Bewegungskriege nicht mehr in nützlicher Frist zur Aktion zu bringen sein werden, daß die überfeinerten Beobachtungs-

Scheutz adds that “agent designers (need to) to ensure that autonomous artificial agents are equipped with the moral and ethical competence to negotiate human societies in order

Referring to this idealist philosophy, Cheng proposed two principles of moral education that demand to “survive the heavenly principle and to abolish the human

A strategy, in this indirect reciprocity game, depends not only on the assess- ment rule (i.e., how the player judges actions between two other players), but also how such an