OXFAM RESEARCH REPORTS 18 DECEMBER 2014

THE INDIAN

OCEAN TSUNAMI, 10 YEARS ON

Lessons from the response and ongoing humanitarian funding challenges

Evacuation signs showing the way to Tsunami safety points. These were erected after the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004. Lho-nga village, District Aceh Besar, Aceh Province, Sumatra, Indonesia (2014). Photo: Jim Holmes/Oxfam.

UNDER EMBARGOED UNTIL 00.01 GMT ON THURSDAY 18 DECEMBER 2014

The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami was a pivotal moment for the humanitarian sector; many lessons were learned and the humanitarian system was strengthened as a result.

However, ten years on, significant challenges remain. Using the case of the tsunami – a rare example of a well-funded humanitarian emergency – this report looks at key lessons from the response and examines why some emergencies receive rapid, generous

funding while others remain virtually ignored by the international community. As

humanitarian need increases, it is imperative that the global community continue to work towards adequate, needs-based funding, and strives to reduce the costs and human impacts of future humanitarian emergencies.

CONTENTS

Glossary ... 3

Summary ... 4

1 Introduction ... 7

2 Social and economic impacts of the tsunami ... 8

3 The largest-ever privately funded response ... 11

4 Lessons Learned and subsequent changes ... 17

5 Ongoing challenges in the funding system ... 25

6 The f actors that drive international funding ... . ... 31

7 Conclusions ... 37

Appendix ... 39

Notes ... 42

GLOSSARY

Capacity building: The process by which people, organizations and societies increase their ability to achieve objectives and effectively handle their development needs.

Disaster risk reduction (DRR): Reducing the impact of natural threats like earthquakes, floods, droughts and cyclones through prevention and preparation.1

Domestic humanitarian response: Emergency humanitarian response from domestic

governments, security and armed forces, local non-government organizations (NGOs), religious organizations and local people.2

Global Humanitarian Assistance (GHA): Run by an independent research organisation, Development Initiatives, the Global Humanitarian Assistance programme analyses humanitarian financing in order to promote transparency and a shared evidence base to meet the needs of people living in humanitarian crises.

Government funding: International giving from governments and the European Commission.

This type of funding is often channelled through institutional donors – i.e. multilateral agencies such as the United Nations.3

International humanitarian response: Emergency humanitarian response from the international community, including governments, individuals, NGOs, trusts, foundations, companies, and other private donors as well as military and security forces.4

Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA): OCHA is the UN body responsible for mobilising and coordinating humanitarian action in order to ease human

suffering in disasters and emergencies. The organization also advocates for the rights of people in need and promotes emergency preparedness and prevention.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development

Assistance Committee (DAC): OECD DAC is an international forum that includes many of the world‟s wealthiest nations and largest donor governments.

Private funding: International giving from individuals, trusts, foundations, companies and other private organizations.5

Resilience: Ability of a system, community or society to resist, absorb, accommodate to and recover from the effects of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner.6

Tsunami Evaluation Coalition (TEC): TEC comprised a group of international donors, UN agencies, NGOs, and research institutes that conducted joint evaluations of the international response to the Indian Ocean tsunami. Reports were published between 2006 and 2007.

UN-coordinated Appeals: Any humanitarian appeals coordinated by the UN, including Strategic Response Plans (SRPs), previously known as Consolidated Appeals Process (CAP) appeals.7

UN Financial Tracking Service (UN FTS): UN FTS is a global database of humanitarian funding compiled and managed by OCHA. Data are self-reported by donors, UN agencies, OCHA, the European Community Humanitarian Office (ECHO) and NGOs.

SUMMARY

The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami was an unprecedented event both in its scale and in the record level of private funding for the relief and recovery effort. An estimated $13.5bn in donations poured in from the international community with roughly 40 percent from private individuals and organizations – making the tsunami the highest-ever privately funded emergency. The high level of international funding allowed humanitarian agencies to mobilize a rapid response and was sufficient to cover the costs of both immediate relief and long-term recovery.In fact, the tsunami was Oxfam‟s largest-ever humanitarian response, with the organization and its partners benefiting an estimated 2.5m people across seven tsunami-affected countries over a five year period, from 2004 to 2009.

The tsunami response was also a pivotal moment for the humanitarian sector. It provided valuable lessons about gaps in the humanitarian system, particularly around the dynamics that influence international funding. Using the case of the Indian Ocean tsunami – a rare example of a well-funded humanitarian emergency – this report examines why some humanitarian

emergencies receive rapid, generous funding while others remain virtually ignored by the international community. These dynamics are particularly relevant today, as the world grapples with an unparalleled number of high-profile humanitarian crises.

INSUFFICIENT AND INEQUITABLE FUNDING

Humanitarian assistance represents vital, life-saving support designed to meet the most basic needs of people in crisis, including food, clean water and shelter. While the tsunami received a record level of private donations, this level of response is rare. In fact, international funding has often failed to meet humanitarian needs, and there are significant inequalities in terms of the level and speed of funding for different emergencies.

Insufficient funding overall

• Over the past decade, international funding has consistently failed to meet one-third of the humanitarian need outlined in UN-coordinated appeals.

• While funding for UN-coordinated appeals reached $8.5bn in 2013, it was still only enough to meet 65 percent of the global humanitarian needs outlined in the appeals.

• The funding gap for UN-coordinated appeals is large, but not insurmountable. In 2013, the funding gap was roughly $4.7bn: less than the combined gross domestic product (GDP) that accrues to the 34 OECD countries in one hour, less than one day‟s combined profits for Fortune 500 companies, and less than the retail value of two weeks of food waste in the USA.

Inequalities in funding for different emergencies

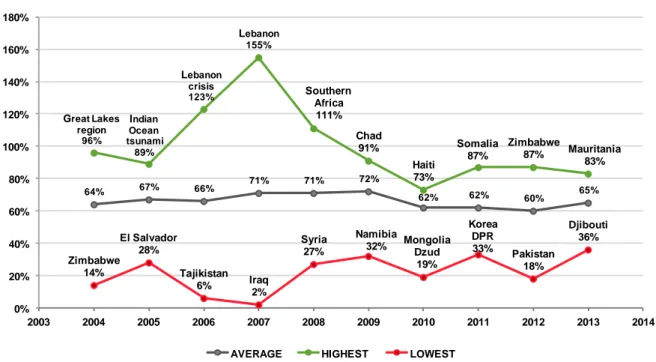

• In a typical year during the past decade, the highest-funded UN-coordinated appeals had four times the percentage of need met than the lowest-funded appeals.

• More than twice the percentage of needs were met in the month after the launch of the UN Indian Ocean tsunami appeal than in the month after the typhoon Haiyan (Philippines) appeal.

• Private funding for UK Disasters Emergency Committee (DEC) appeals averages $107m (£67m) for natural disasters; more than three times the average amount for conflict-related crises ($34m (£21m)).

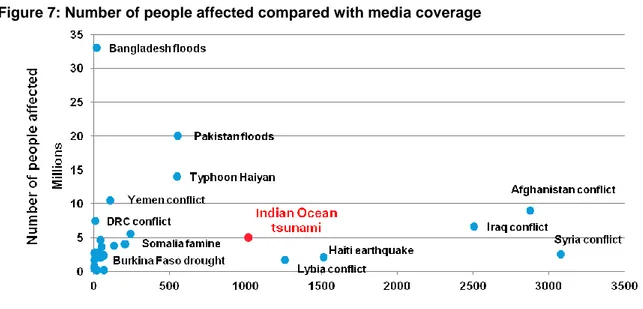

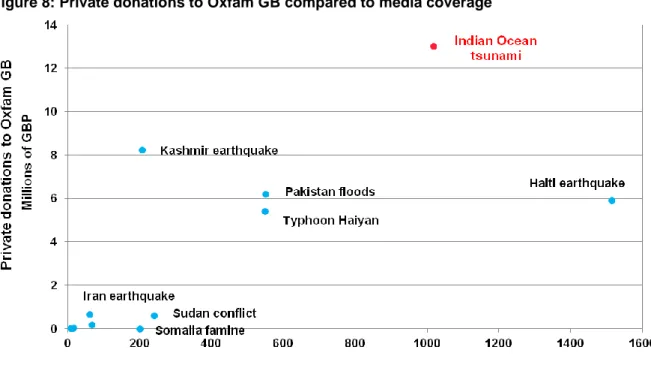

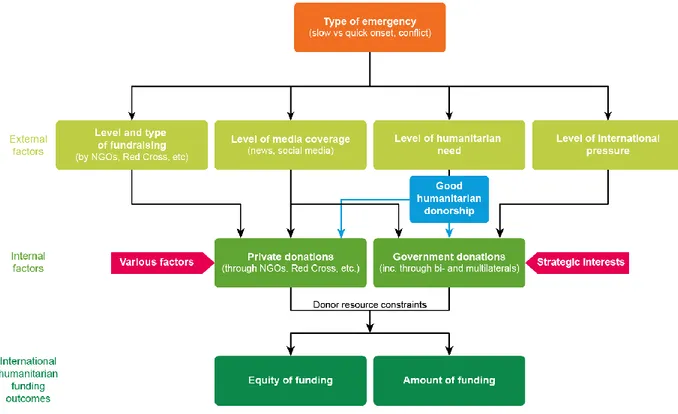

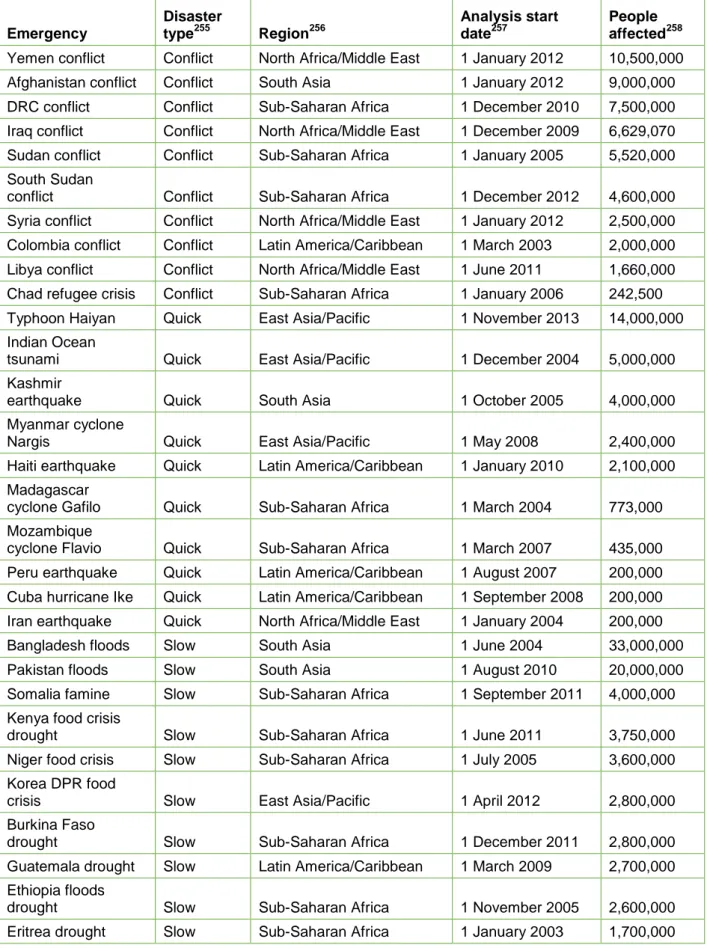

FUNDING DRIVEN BY FACTORS OTHER THAN NEED

Factors other than humanitarian need often influence the level and speed of international funding for emergencies. Many government donors (the largest humanitarian donors) have stated commitments to providing impartial, needs-based assistance, yet other factors – such as strategic geopolitical and economic factors, international pressure and media coverage – continue to influence them. Private donations, which comprise roughly one-quarter of

international funding, are heavily influenced by factors other than humanitarian need, such as level of media coverage and fundraising through public-facing humanitarian appeals. Private donors are also influenced by a range of other factors, including type of emergency, perceptions about the impact of donations and ability to identify with affected populations.

CONCLUSIONS

Since the 2004 tsunami, the humanitarian sector has taken positive steps towards improving the efficiency, equity and quality of humanitarian responses. However, important challenges remain, particularly around humanitarian funding. Timely, adequate funding is important because it can reduce the human impact of a crisis and allow for high-quality, sustainable interventions that build the capacity of communities to respond to, and prepare for, future emergencies. It is imperative that the global community continues to work towards sufficient, impartial

humanitarian funding – particularly as global humanitarian need is on the rise and is predicted to increase over the next century.

The research for this report points to the following ways to reduce the impact of future humanitarian emergencies and continue to improve the equity and quality of humanitarian responses.

Increase international funding and work to reduce the impact of future emergencies

With the combined resources of the international community, it should be possible to close the funding gap for UN appeals. Closing this gap would provide much-needed relief to millions of people affected by natural disasters and conflict every year. Over the long term, the most efficient and sustainable way to reduce the financial costs and human impacts of humanitarian emergencies is to work to prevent these crises before they happen and to build local capacity to respond to and recover from disasters. This includes reducing people‟s vulnerability to disaster through poverty reduction and strengthening of public services. Unfortunately, investment in prevention and preparedness remains low, accounting for just six percent of OECD DAC humanitarian assistance in 2012 and an estimated 0.7 percent of OECD DAC non-emergency development assistance in 2011.

Secure impartial, needs-based funding

Government donations: When consistently put into practice, formalized commitments that seek to hold government donors accountable to the principles of Good Humanitarian Donorship, can help to ensure that donations are based on humanitarian need. Moreover, increased government contributions to pooled funds can increase the equity and speed of humanitarian responses, as long as funding is quickly available to front-line humanitarian organizations. More research is needed to determine whether further efforts, such as a model of mandatory

government contributions toward UN appeals, would be a feasible and efficient way to increase annual funding commitments as well as the overall efficiency and quality of humanitarian responses.

Private donations: Due to unequal levels of media coverage for different humanitarian

emergencies and the range of other factors that influence private donors, private donations may never be truly proportional to humanitarian need. Nonetheless, steps could be taken to improve the impartiality and efficiency of these donations, such as channelling more funding through regular giving, and private contributions to multilateral and NGO pooled funds. However, further research is needed to understand whether encouraging more regular giving and donations to pooled funds might impact the overall level of private donations. These efforts would likely only be successful if humanitarian agencies worked to build the trust of private donors and used good communication strategies to demonstrate the impact of donations. As it stands, NGOs receive a large portion of humanitarian income from costly, time-intensive public appeals while private contributions to pooled funds remain low: in 2013, the UN‟s Central Emergency

Response Fund (CERF) received just over $100,000 from private donors.

Continue to improve the quality, efficiency and sustainability of responses

While there has been considerable progress since the 2004 tsunami, more effort is needed to improve the humanitarian system in four key areas:

• coordination, especially as it relates to the ability to address cross-cutting issues like gender, disaster risk reduction (DRR) and building domestic capacity;

• inclusive responses that are sensitive to the needs of marginalized and vulnerable groups;

• capacity building and support of local civil society, particularly for disaster preparedness and response; and

• conflict-sensitive approaches that either de-escalate or at least avoid exacerbating tensions between different groups.

Gather better humanitarian funding data

There are systems in place to record humanitarian donations, but there is a need for more accurate and timely reporting. This is especially true for private donations, which are currently underreported. There is also very little data available on remittances, non-monetary donations of goods and services, and domestic humanitarian responses.

1 INTRODUCTION

Tsunami funding broke the norm

26 December 2014 marks the 10-year anniversary of the Indian Ocean tsunami, one of the largest and most destructive natural disasters in living memory. The emergency response which followed was unprecedented in the speed and level of international humanitarian funding that it generated, particularly from private donors, including individuals, trusts, foundations, companies and other private organizations. Even today, the tsunami response remains the largest-ever privately funded disaster response.

In the days and months following the tsunami, international donations came in at a record rate.8 An estimated $13.5bn was raised for the relief and recovery effort,9 with up to $5.5bn of this (roughly 40 percent) from private donors.10 This equates to approximately $2,700 per person affected by the disaster,11 more than twice the 2004 GDP per capita of the two worst affected countries: Indonesia and Sri Lanka.12 Due in large part to the generosity and speed of international funding, humanitarian organizations were able to mobilize a massive relief effort after the tsunami – one of the largest humanitarian responses in history.

Unfortunately, the swift and generous response to the tsunami remains the exception rather than the norm. International funding often does not meet humanitarian need. While funding for UN- coordinated appeals reached $8.5bn in 2013, it was still only enough to meet 65 percent of need.13 In fact, over the past decade, international funding has consistently failed to meet roughly one-third of the humanitarian need outlined in UN-coordinated appeals.14 Moreover, the funding raised for different humanitarian emergencies remains highly unequal.

Putting the tsunami in context

This research report begins by reviewing the social and economic impacts of the tsunami, eliciting key lessons from the evaluations of the humanitarian response, particularly around funding. It then provides an overview of humanitarian funding trends over the past decade, highlighting inadequacies in the overall level of funding and inequalities in the funding system. Next, the report reviews existing research, emphasizing the fact that humanitarian funding is often driven by factors other than need. Finally, it presents conclusions about how the humanitarian system has evolved since the tsunami, the ongoing challenges that it faces, and potential ways to reduce the impact of future emergencies and to continue to improve the equity and quality of humanitarian responses.

As humanitarian need continues to rise, it is imperative that the international community

continues to work towards adequate, needs-based humanitarian funding and strives to reduce the costs and human impact of future emergencies. In 2013, 144 million people were displaced by conflicts or affected by natural disasters, 65 million of whom (roughly the population of the UK or the combined populations of California and Texas) were targeted for assistance through UN interagency funding appeals.15 Moreover, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that by the end of 2013, the number of refugees, asylum-seekers and internally displaced people around the world rose to 51.2 million – more than at any time since the Second World War.16 Even as domestic humanitarian responses17 become increasingly important, international

humanitarian funding continues to play a vital, life-saving role. This is especially true today, as the world grapples with an unparalleled number of high-profile humanitarian crises. Iraq, Gaza, Syria, Ukraine and the Ebola outbreak in West Africa are all competing for international attention and funding. Meanwhile, millions of people are being affected by lower-profile, but just as devastating crises, in South Sudan, Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Central African Republic (CAR) and Pakistan, to name a few. Furthermore, other crises, such as the ongoing

18

2 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC

IMPACTS OF THE TSUNAMI

On the morning of 26 December 2004, a 9.1 Richter scale earthquake struck off the western coast of the Indonesian province of Northern Sumatra.19 It was the third-largest earthquake in recorded history20 and its sheer force sent a series of tsunamis surging across the Indian Ocean, some at speeds of up to 500km per hour, affecting people in 14 countries.21 As the epicentre was close to densely populated coastal communities, the disaster caused significant loss of life. An estimated 230,000 people died and 1.7 million people were displaced from their homes.22 Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India and Thailand were the hardest hit, with 167,540 people killed in Indonesia alone.23

The social and economic impacts of the emergency were devastating. In the early days after the tsunami, approximately five million people were in need of humanitarian assistance, including food, water and shelter.24 Countries affected by the tsunami were low or middle-income

countries, which tend to suffer more severely during humanitarian emergencies and take longer to recover.25 Furthermore, many of the affected countries were already dealing with widespread and deep-rooted problems, such as poverty and inequality, which the tsunami only served to compound.26

Disproportionate impact on poor and vulnerable groups

As is often the case in a humanitarian emergency, poor and vulnerable groups suffered most from the tsunami.27 While everyone affected by it experienced a decline in their living standards, the poor were hardest hit by loss of land, housing and livelihood opportunities. This is because the poor had fewer resources available (in terms of savings, insurance and other safety nets) with which to recover from the impact of the tsunami.

The disaster also had a disproportionate impact on women, children and older people.28 Across

men.29 Mortality was also higher for children (14 and under) and older people (50 and older), with both groups more than twice as likely to have lost their lives in the tsunami as adults aged 15–49.30 Adult males under 50 years of age had the highest chance of survival overall.31 The inability to swim may have been one factor behind higher mortality rates among women.32 Moreover, an Oxfam study in India found that when the tsunami hit, many men were out at sea fishing where the waves passed safely under their boats before swelling up as they reached the shore.33 Meanwhile, women were exposed to danger as they waited on the beach to collect the fish and take them to market. Oxfam also found that many women lost their lives trying to save their children and elderly relatives. Whatever the reasons for the higher mortality rates among women, the tsunami resulted in gender imbalances in many communities, with large numbers of men becoming single parents.34

Severe economic impacts

An aerial view of the vast destruction of the Indonesian coast, between the towns of Banda Aceh and Meulaboh, caused by the Indian Ocean tsunami (2005). UN Photo/Evan Schneider

In addition to the social effects, the tsunami had major economic impacts, damaging vital infrastructure in many countries and requiring billions of dollars in reconstruction costs. The Tsunami Evaluation Coalition (TEC) – a group of 45 bilateral donors, multilateral organizations and international NGOs that conducted several large-scale evaluations of the response – estimated that total damages reached $9.9bn, with almost half of those sustained in

Indonesia.35 The fishing industry was badly affected. In some cases, waves travelled up to 3km inland, destroying boats and disrupting livelihoods among fishing communities.36 The damage to the fishing industry in Sri Lanka was particularly severe because the tsunami hit on a Buddhist holiday. As a result of this, many fishermen were not at sea and had left their boats and fishing gear on the beach, where they were destroyed by waves.37

Thailand and the Maldives also experienced significant economic losses due to their heavy reliance on tourism. While loss of life as a result of the tsunami was much lower in the Maldives than in many other countries, economic damages were estimated at nearly 80 percent of the country‟s annual gross national income (GNI).38

Box 1: Responding to the damage in the fishing community of Lhok Seudu, Aceh, Indonesia

T Buhari, 40, works on sorting and arranging fishing nets in Lhok seudu Village port. District Aceh Besar, Aceh Province, Sumatra, Indonesia (2014). Jim Holmes/Oxfam GB

This small fishing community in Lhok Seudu, coastal Aceh Bezar, was severely damaged by the earthquake and tsunami. Oxfam visited this village by boat (from Peunayong) and understood the desire of the villagers to stay put, rather than be relocated to houses further away from the coast. The community relied totally on fishing and needed to be situated close to their boats and the sea.

Ten years on and the 50 Oxfam-built houses have been maintained and modified by the community. The latrines in the houses are still working effectively, and the gravity fed water supply on a nearby hill has worked successfully to provide water for to the houses. The water catchment tank on the nearby hill was damaged in late-2014 by landslides following weeks of rain. The villagers are drawing up proposals to fix it. In November, T. Buhari, a resident of Lhok Seudu, reflected on Oxfam‟s response in his community, „I had never heard of Oxfam before the tsunami came. Our village was badly hit, but luckily only three villagers living here died. People in other nearby villagers were harder hit, and out of about 1,000 people living around here, 300 people died on that dreadful day.

„After the wave, a few of us went into Banda Aceh to see if we could find someone to help us. I was in one of the camps for displaced people and met with Habiba who worked for Oxfam. They arranged to come to our village to assess the damage and to see if they could help. They had to come by boat because the road here was too damaged.

„After the assessment, Oxfam said that they could help us and after this the work started and Oxfam was here with us for three years. We had a relationship with Oxfam, and we felt safe in [its] hands. There were many different NGOs working in Aceh, but Oxfam was the only one to work in our village. We trusted Oxfam because [it] listened to us and

communicated with us to find out about our needs. [It] understood that we were fishing people and that we wanted to stay here. [It] didn‟t force us to move away from our lives.

After these three years, our village felt better than it was before because we all had houses and water.‟

3 THE LARGEST-EVER PRIVATELY FUNDED RESPONSE

At the time, the UN Emergency Coordinator described the tsunami response as the „most generous and immediately funded emergency relief effort ever‟.39 An estimated $13.5bn was raised by the international community for the tsunami response,40 making it the largest ever private response to a disaster (although not the largest government response41).42 According to the tsunami funding review carried out by the TEC, the exceptional international funding response meant that international resources (combined with local resources) were sufficient to cover the costs of both relief and reconstruction.43

Figure 1: Estimated international funding for the tsunami response as of December 2005 ($)

Based on data reported by Development Initiatives from OECD DAC and national donor reports. Global Humanitarian Assistance Report (2006)

The largest portion of international funding (an estimated 45 percent) came from government donors, closely followed by private donors (40 percent) (see Figure 1).44, 45 In all, private donors gave between $3.2bn and $5.5bn towards the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami relief effort.46 The majority of private donations (70 percent) went to just a few large organizations: the 10 largest NGOs (including Oxfam), the Red Cross Movement and UNICEF.47 While the response to the tsunami was not the largest government response, it did involve the largest number of individual government and institutional donors.48 However, just five government donors were responsible for providing over 50 percent of government funding: USA, Australia, Germany, the European Commission and Japan.49

In total, 99 countries contributed to the response, including 13 that had never before made a recorded contribution to a disaster.50 In addition to this, a survey in Germany found that roughly 30 percent of public donations were from people that had never donated to the respective charities before.51 Surveys carried out by the TEC in Spain, France and the USA found that approximately one-third of the population in each country donated to the tsunami response.52 There was also a record level of donations in the UK (see Box 2).

Private donations

$5.4bn

40%

Loans and grants

$2.0bn

15%

Government donations

$6.4bn

45%

Box 2: Funding from private donors in the UK

The UK Disasters Emergency Committee (DEC) is one of the largest fundraising coalitions in the world. It helps coordinate fundraising efforts for 13 UK humanitarian aid agencies, including the British Red Cross, Oxfam, Plan UK and Save the Children.

The DEC launched an appeal for the Indian Ocean tsunami on 29 December 2004, raising a record-breaking £392m ($627m).53 In just two months, the DEC tsunami appeal received eight times the amount of donations that it had received for its Sudan appeal, which had been running for four times as long.54

Due to the scale of destruction caused by the tsunami, the DEC decided to spend the funds over a period of three years to allow for short-term relief as well as long-term recovery.55 The DEC reports that more than 750,000 households were helped by DEC funds, which were mostly spent in Sri Lanka, Indonesia and India.56 In total, DEC member agencies constructed more than 13,700 houses, 55 schools and 68 health centres with funds raised by the UK public.57 In a 2009 interview with the BBC, Brendan Gormley, the former DEC Chief Executive, stated that 80 percent of all UK households supported the tsunami appeal.58

While it is difficult to determine a reliable figure for the domestic response to the tsunami in affected countries, it is clear that local and national governments, security and armed forces, local NGOs, religious organizations and local communities all played an important role in responding to the disaster. Moreover, several tsunami-affected countries were, and still are, large recipients of international remittances – money sent home by those working abroad.

Remittances are often an important source of support for populations affected by humanitarian crises.59 While it is difficult to ascertain what proportion of this money was used for tsunami relief, India was the largest global recipient of remittances in 2005 (of the countries for which the World Bank has data) with over $22m; Indonesia was the ninth largest recipient, with $5.4m;

and Sri Lanka was the thirty-fifth largest recipient, with approximately $2m.60

ONE OF THE WORLD‟S LARGEST HUMANITARIAN RESPONSES

In the first few days after the disaster, local people provided the majority of immediate life- saving assistance.61 However, within days, a record number of humanitarian agencies had arrived in affected areas to assist with the response. Even today, the Indian Ocean tsunami remains Oxfam‟s largest-ever humanitarian response and the first-ever coordinated response by the entire Oxfam confederation (see Box 2). One of the biggest challenges of the

humanitarian response was the sheer scale of the disaster. This was an unprecedented event, spanning 14 countries and affecting roughly five million people.62 These challenges were compounded when another earthquake severely damaged the Indonesian island of Nias in March 2005.

Despite the scale of the emergency, generous international assistance allowed for a quick initial recovery effort. Within a few months, children were back in school in all countries and many health facilities and other services had been restored.63 Six months into the response,

approximately 500,000 people had been temporarily housed in Aceh province, Indonesia, with approximately 70,000 people still living in tents.64 The fishing industry in Sri Lanka was rapidly rebuilt; more than 80 percent of damaged boats, equipment and markets were restored within six months and 70 percent of households had regained a steady income.65 Within half a year, tourists had also begun to return to Thailand and the Maldives.66

Through the combined efforts of local communities, local and national governments and the international community, most tsunami-affected areas have been rebuilt to better withstand future natural disasters. The city of Banda Aceh, in the worst hit region of Indonesia, stands as an example of this transformation. At the end of 2012, when the World Bank closed its Multi- Donor Fund (MDF) for Aceh and Nias, it described how roughly $7bn in contributions from the international community and Indonesian government had driven a massive reconstruction effort.67

There has been significant progress on disaster risk reduction (DRR) efforts in Indonesia. In March 2014, UNICEF described the tsunami response as a model for the philosophy of „building back better‟, noting that communities are now safer and better able to withstand future natural disasters.68 Since the tsunami, the Indonesian government has invested in emergency education and constructed hundreds of earthquake-resistant schools.69 Schools have also begun to conduct regular earthquake drills. Public health improvements, ranging from

immunization programmes to antenatal care and malaria control, have also made families and communities more resilient and less vulnerable to future disasters.70 While there had long been disaster management structures in place in Indonesia, the tsunami created support for their overhaul. In 2007, Law 24/2007 was passed, which mandated a new focus on risk management and prevention, and enshrined protection against the threat of disaster as a basic human right.71 Today, the city of Banda Aceh stands out because of its newly constructed buildings, wide new roads and modern waste management and drainage systems.72 In a January 2014 article, The Guardian reported that, by the end of 2010, more than 140,000 houses, 1,700 schools, nearly 1,000 government buildings, 36 airports and seaports and 3,700km of road had been built across Aceh province.73 It is difficult to believe that the bustling town centre was once the scene of one of the worst natural disasters in living memory. Nonetheless, poignant reminders of the tsunami remain. The two-and-a-half tonne electrical barge that was swept approximately 2km inland now stands as a memorial to the tsunami and is a reminder of its immense power.74 The Sri Lankan government has also made significant efforts towards better disaster preparedness in order to minimize the impact of future disasters. In 2005, the government certified the Disaster Management Act, which included the formation of a National Council of Disaster Management and Disaster Management Centre, to implement the directives of the Council at the national, district and local level.75 In addition, the Sri Lankan National Institute of Education has incorporated DRR into the school curriculum and the Ministry of Education has developed National Guidelines for School Disaster Safety.76

Box 3: The Indian Ocean tsunami early warning system

When the tsunami hit, there were no early warning systems in place in countries with coastlines along the Indian Ocean. Parts of Indonesia were struck by waves within 20 minutes of the earthquake, but it took hours for the waves to reach countries further away.77 An early warning system could have saved many lives further from the epicentre.

After the tsunami, the UN Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) and partners began working on an Indian Ocean tsunami early warning system. By 2006, a provisional system had been established, and by 2012, a network of seismographic centres, national warning centres, agencies, and coastal and deep-ocean stations was in place to warn communities about potential tsunamis.78

In 2012, an earthquake measuring 8.6 on the Richter scale struck in roughly the same location as the 2004 tsunami. While the 2012 earthquake did not trigger a tsunami, it did test the functioning of the early warning systems. The Head of the UN IOC reported that, while gaps remained, the three systems in Indian Ocean countries (Australia, India and Indonesia) functioned perfectly.79 Thanks to this early warning system, the Indian Ocean region is now better prepared to reduce the human impact of future tsunamis.

OXFAM‟S LARGEST-EVER HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE

An Oxfam project officer checks a water pipe at the Oxfam pumping station, Aceh, Indonesia (2005).

Photo: Jim Holmes/Oxfam

Oxfam raised $294m for the tsunami relief effort, with over 90 percent from private donors.80 The majority of funding (54 percent by October 2008) came to Oxfam Great Britain, followed by Oxfam America (11 percent), Oxfam Novib in the Netherlands (10 percent) and Oxfam Australia (7 percent).81 Oxfam received donations through public appeals and joint-agency appeals – the largest of which was the DEC Appeal in the UK, which brought in $126m in income to Oxfam.82 The speed of the donations was unprecedented, with more than 80 percent of total donations received after only one month.83 Due to the large amount of funding generated through appeals, Oxfam established the Oxfam International Tsunami Fund in the first few months after the tsunami.84 This fund helped to manage and coordinate the tsunami response across the Oxfam confederation, until it closed in December 2008.

Oxfam helped an estimated 2.5 million people in tsunami-affected areas between 2004 and 2009.85 It worked alongside more than 170 local, national and international partner

organizations to carry out relief, rehabilitation and recovery programmes across Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, the Maldives, Myanmar, Thailand and Somalia.86 In the early days after the tsunami, Oxfam conducted rapid assessments of the damage and began supporting people‟s immediate needs. The organization delivered clean water and provided blankets and other non- food emergency items.87 Along with partners, it also provided temporary shelter for over 40,000 people made homeless by the tsunami.88 As the response progressed, Oxfam shifted its focus from short-term relief to longer-term recovery work. Many of Oxfam‟s programmes targeted vulnerable and marginalized groups, with a particular emphasis on gender.89

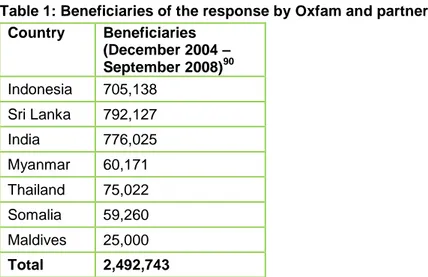

Table 1: Beneficiaries of the response by Oxfam and partners Country Beneficiaries

(December 2004 – September 2008)90 Indonesia 705,138

Sri Lanka 792,127 India 776,025 Myanmar 60,171 Thailand 75,022 Somalia 59,260 Maldives 25,000 Total 2,492,743

Oxfam continued to provide clean water, delivering over 300m litres to Aceh over a three-year period.91 In all, Oxfam and its partners improved or constructed more than 10,800 wells, 90 boreholes and 55 gravity flow water systems, and built a municipal water system to supply 10,000 people in Aceh province.92 Oxfam and partners also built 12,000 latrines, distributed over 67,000 hygiene kits and trained over 2,500 health volunteers.93 In the communities where it operated, Oxfam provided training sessions to help local communities to manage and maintain their own water systems.

The organization and its partners also reached approximately 960,000 people with livelihood development initiatives. These initiatives included employing tsunami survivors to help with clean-up projects and longer-term programmes to restore livelihoods by replacing fishing boats, constructing docks in Indonesia and Somalia, supporting improved agricultural

practices and replacing livestock.94 In the countries where it worked, Oxfam constructed over 2,900 permanent houses, cleared more than 100km of roads and built 31 bridges to allow access back into devastated communities.95 With help from partners, the organization also constructed or repaired more than 100 schools in Indonesia and Myanmar.96 In addition, Oxfam advocated for the rights of tsunami survivors, including working to secure housing for renters and squatters and improving women‟s input into the relief and recovery effort.97

Box 4: Volunteer maintenance of gravity flow water systems in Aceh, Indonesia

Dahlan, 52, has been working on the maintenance of the gravity flow water system installed by Oxfam almost 9 years ago, following by the Indian Ocean tsunami, Lampuuk, District Aceh Besar, Aceh Province, Sumatra, Indonesia (2014). Jim Holmes/Oxfam GB

Lampuuk settlement, composed of five villages, was heavily damaged by the 2004 tsunami. Dahlan has been working on the maintenance of the gravity flow water system installed by Oxfam almost nine years ago.

„I lost my wife and two children in the tsunami. We were escaping on two motorbikes. I was in front with one child, and my wife was behind with our two other children. The wave just swept my wife and children away.

„All of this area in Lampuuk was ruined. I took my surviving child up into the hills for two years while Lampuuk was re-planned. This was done so each of the five villages here had access to a road. We all gave up claims to our own land for the benefit of the village to make way for a new road to be built. If villagers lost land because of the road, they were then given more land behind their house.

„Each village has a water committee, and I am the water engineer for Lambaro... I do whatever is needed to maintain and clean the system. I work with the other four engineers to make sure that the catchment pool is clean and that the pipes are de-silted, and also in the village. When one of the engineers is busy, we cover for each other and when there is a lot to do, we work together. This is not a full time job. I am a farmer and fisherman as well. I don‟t get paid for this – it is voluntary – we depend on donations from the community. Some houses can pay 1,000 IDS a month ($0.08), but other pay less. This pays for operational costs, for fuel, equipment and the running of the committees.

„Everything was working well with the system up to five days ago [November 2014] when we had heavy rain for five days. One of the pipes broke and some mud got into the system we had to clean out. We replaced the pipe and water is flowing again. When it is the dry season, our supply is less because the catchment pool is quite small. This is why we have built another pool higher up the hill to pipe water down to the main pool to keep the system going.

„We had a lot of training from Oxfam to learn how to manage and maintain the whole system... The water may be slow sometimes, but all of the people in our villages like the system and are glad that Oxfam worked here.‟

4 LESSONS LEARNED AND SUBSEQUENT CHANGES

‘The tsunami, combined with the Darfur crisis of 2004 that preceded it and the [2005] Pakistan earthquake that followed it... will probably be seen in future as one of those key ‘move forward’ moments... as a cluster of crises that really stretched the humanitarian system and pushed it to be more efficient, more coordinated and more effective... It wasn’t that these were brand new ideas, but they were all things that we learned a lot more about through the course of such an enormous response.’

Interview with Jane Cocking, Oxfam GB Humanitarian Director, 8 November 2014

Several large-scale evaluations of the tsunami response were commissioned, which provided valuable lessons for the humanitarian sector. In 2006, the TEC published a series of evaluation reports based on extensive research, including large-scale surveys in tsunami-affected regions.

Three years later, the Swedish development organization, Sida, led a follow-up study, which further evaluated the success of long-term development programmes. In addition to the TEC and Sida evaluations, there have been numerous analyses by researchers and humanitarian aid organizations, including the Red Cross, the World Health Organization (WHO), UN agencies and Oxfam. The lessons learned from these evaluations have had a considerable impact on how the world responds to humanitarian emergencies. While each analysis addresses different aspects of the tsunami response, several broad themes emerge, which are discussed in more detail below.

A. STRENGTHENING THE FUNDING SYSTEM

While the speed and level of funding for the tsunami allowed for a rapid response effort, it also created problems for NGOs not used to handling such a quick influx of funds. In fact, Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) closed its tsunami appeal after just one week, having raised six times more for the tsunami response than it had raised for the Darfur crisis in two months.98 By mid- January, Oxfam also began closing funding appeals and urging the public to donate to other, less high-profile emergencies.99, 100 The amount of public funds raised for the tsunami compared with other large-scale humanitarian disasters also highlights the unequal and often unfair flow of funds for emergencies.101

Efforts to make humanitarian funding more equitable

While many governments have long-standing commitments to the Good Humanitarian

Donorship principles – a set of internationally recognized standards set out in 2003 to provide a framework for more effective donor behaviour102 – few are as formalized as the European Consensus. Adopted by European Union (EU) Member States in 2007, the European Consensus is a commitment to humanitarian principles, including „humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence‟, and to following good practice in humanitarian responses.103 While the principles of the European Consensus are admirable, recent analysis suggests that they are not always put into practice. A 2011 report led by a number of NGOs concluded that while the European Consensus is an important tool for encouraging principled humanitarian assistance, progress among EU member states has been mixed.104 A subsequent 2014 analysis found that, while EU member states and NGOs operating within them believe that the Consensus adds value by promoting humanitarian principles, NGOs often feel that these principles are not consistently acted on.105 Specifically, NGOs perceive that funding decisions are frequently tied to „non-humanitarian‟ considerations.

In existence before the tsunami, the Forgotten Crises Assessment (FCA) Index developed by the European Community Humanitarian Office (ECHO) is another effort to make funding more equitable.106 The FCA Index seeks to raise awareness about the world‟s „forgotten crises‟ – humanitarian emergencies that fail to receive donor and media attention. This index continues to serve as a useful tool for identifying unmet humanitarian need.

The increasing role of pooled humanitarian funds

An increasing amount of international humanitarian assistance is now channelled through pooled funds.107 These funds are designed to aid flexibility and speed when responding to humanitarian crises and to make funding more impartial.108 The tsunami was a partial catalyst for the launch of the expanded UN Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) in 2005. In addition to CERF, there are several country-level pooled funding systems designed to support UN-coordinated response plans (common humanitarian funds or CHFs) and to fill unexpected needs that arise outside of coordinated response plans (emergency response funds or ERFs).109 In 2013, pooled funds like the CERF received more than $1bn (4.7 percent of all humanitarian assistance).110 Nearly half of this was distributed through the CERF.111 More recently, NGOs have also begun to lead pooled funds, including the Start Fund, at the global level, and other country-focused pooled funds. Launched in April 2014, the Start Fund is specifically designed to „fill gaps‟ in the emergency funding system by providing an early response for emergencies that fail to attract sufficient funding.112

A 2011 independent evaluation of the CERF found that the fund has increased the predictability of funding for humanitarian emergencies and is the fastest external funding source for UN agencies.113 The CERF has also increased humanitarian coverage by funding vital, but often underfunded, services, such as transportation and communications.114 However, a common criticism of the CERF is that funds cannot be dispersed directly to NGOs and can only reach them through agreements with recipient UN agencies.115 This has sometimes resulted in delays in funds reaching NGOs, though it has been less of a problem in countries with CHF/ERF funds or other sources of rapid funding directly available to NGOs.116 All in all, investment into pooled funds is a positive step towards improving the impartiality and speed of funding for humanitarian crises because pooled funds allocate money based on assessments of humanitarian need and can often disburse funds very quickly. While government contributions to pooled funds are on the rise, they tend to attract little funding from private donors. For example, in 2013, the CERF received just over $100,000 in funding from private sector and civil society donors.117

B. COORDINATION OF THE HUMANITARIAN SYSTEM

Generous international funding undoubtedly improved lives for tsunami survivors, but it also resulted in challenges of coordination. At one point during the summer of 2005, there were close to 200 international NGOs operating in Aceh province alone.118 Large amounts of private donations sometimes put pressure on NGOs to work outside of their areas of expertise, often resulting in inconsistent quality of construction projects and livelihood development

programmes.119 120 A consistent theme across evaluations was the need for better coordination among humanitarian agencies.121

The cluster approach, and quality and accountability initiatives

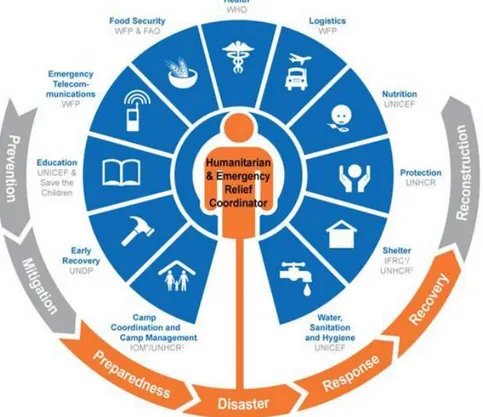

Figure 2: The UN Cluster System

Source: UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

In late 2004, the UN commissioned the Humanitarian Response Review in response to frustrations over the international response to the crisis in Darfur.122 The review analyzed responses to several complex emergencies and natural disasters, including the Indian Ocean tsunami.123 This comprehensive review led to major reforms in how the humanitarian system is coordinated, known as the Humanitarian Reform Agenda.

One of these reforms introduced the Cluster Approach, which nominates organizational leaders to coordinate work in their sector of expertise.124 A 2010 evaluation, commissioned by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), maintained that while the new approach has improved humanitarian responses, it has had difficulty addressing issues such as gender and disaster risk reduction, which cut across sectors.125 Moreover, the evaluation found that local actors (local governments, NGOs, etc.) are often excluded from the response even when there is substantial local capacity available. To address these criticisms, the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC)126 Transformative Agenda, agreed in 2011, focused on

strengthening cross-cluster coordination and on systems to ensure that clusters are only deployed when it makes sense to do so.127

In addition to the Cluster Approach there is now an increased emphasis on humanitarian standards. Three of the most well-established and internationally recognized quality and accountability initiatives are the Humanitarian Accountability Partnership, People In Aid and Sphere, which were all established before the tsunami.128 These set out minimum standards for life-saving activities such as water supply, sanitation, food provision, shelter and health. Efforts are currently under way to harmonize the three initiatives into a Core Humanitarian Standard (CHS) in order to increase coherence and make it easier for humanitarian practitioners to put them into practice.129

C. ADDRESSING THE NEEDS OF VULNERABLE AND MARGINALIZED POPULATIONS

The TEC‟s joint evaluation report identified several inequalities in the way that assistance was delivered. These included national inequalities (for example, between conflict and non-conflict areas), inequalities by sector (for example, between the fishing sector and other sectors), geographical inequalities (between areas that were more and less accessible), and social inequalities (between poor and marginalized groups and better-off households).130 One factor that drove these inequalities was a focus on replacing physical assets, such as houses or boats.131 This meant that households which had owned these kinds of assets before the

tsunami (and thus tended to be better-off) had them replaced as part of the response, effectively providing more aid to better-off households. In addition, some groups, such as the fishing communities in India, were better organized and therefore better able to access aid.132

Moreover, while there were examples of good practice, the TEC‟s joint evaluation of the tsunami response noted that the needs of women, children and older people were often overlooked.133 Women tend to be more vulnerable when natural disasters strike because they often have less access to resources and because emergency living conditions can create higher work burdens and increase domestic and sexual violence.134 A survey conducted in Sri Lanka as part of the TEC joint evaluation found that, in general, women were less satisfied with the tsunami response than men.135 In particular, many women felt that international agencies could have done more to protect women living in camps. Additionally, women were sometimes

disadvantaged in terms of access to livelihoods and asset recovery programmes because many rehabilitation activities centred on male-dominated sectors, such as fishing, overlooking the livelihoods of women and other marginalized groups.136,137 Many women felt that livelihood projects geared towards them (such as mat-weaving) were not sufficient to provide a decent income.138

Increased efforts towards equitable humanitarian responses

The tsunami prompted more research into how disasters affect women differently. For example, a 2007 study of more than 140 countries covering the period from 1981 to 2002 found that natural disasters (and their impacts) kill more women than men.139 This effect is even more pronounced for women from poorer backgrounds. A study conducted in Aceh, Indonesia, after the tsunami highlighted ways to ensure that humanitarian responses are sensitive to gender.

These include:

• involving women representatives in the coordination of aid distribution;

• providing separate toilet/latrine facilities and safe accommodation to ensure privacy and protect women from sexual harassment;

• providing accessible health facilities to provide care for pregnant women and babies as well as access to contraceptives; and

• prioritizing livelihood activities for women as well as men, especially women heads of household.140

While international standards that promote equitable and inclusive humanitarian responses (such as the Good Humanitarian Donorship principles and Sphere) were already in place prior to the tsunami, evaluations of the disaster focused attention on the need to consistently put these principles into practice. A recent evaluation of the humanitarian system noted that while there has been increased attention given to gender and to providing more inclusive

humanitarian responses, more work is needed to ensure that the needs of marginalized and vulnerable groups are consistently and adequately taken into account.141

Box 5: Income development for poor rural women in Sri Lanka

A women‟s goat-rearing group in the tsunami-affected community of Komari, eastern Sri Lanka (2007). Howard Davies/Oxfam

After the tsunami, Oxfam and its partner SWOAD helped poor rural women to boost their incomes. In the village of Thandiadi in eastern Sri Lanka, livelihoods were decimated by the tsunami. Many families lost their homes, as well the goats that were a vital source of income. Oxfam and SWOAD rebuilt 40 houses and 82 toilets, and then started groups to help women rear hybrid goats.

At the time, Ranjani, 37, a member of one of these groups explained, „Each member puts 50 rupees ($0.44) into the savings fund each month. So far we have saved 8,700 rupees ($77). We can use this fund for two purposes: an emergency fund for members in need, and to purchase more goats.‟

As well as training the women in practical skills, such as how to look after the goats and maintain their sheds, SWOAD also helped them to understand their rights and

entitlements, and facilitated access to government departments.

D. LOCAL HUMANITARIAN PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE CAPACITY

A mantra that emerged during the relief and recovery effort after the tsunami was „build back better‟ – the idea being that aid organizations should not only restore communities, but build safer, more resilient communities to withstand future disasters. However, despite the emphasis on building back better, many organizations have been criticized for prioritizing speed over quality and undermining rather than promoting local capacity.142 The 2009 Sida evaluation notes that this became less of a problem in the latter part of the humanitarian response.

Growing focus on DRR and resilience

‘Coping with the expected strains on the humanitarian system will mean a shift from global to local... Having local organizations already on the ground primed to go will increase both the speed and the efficiency of the aid effort and ultimately will save more lives.’

Jane Cocking, Oxfam GB‟s humanitarian director, „Disaster relief must be more local and national, Oxfam says‟, the Guardian, 7 February 2012. http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2012/feb/07/disaster-relief-local-response Building local capacity to prepare for, and respond to, humanitarian emergencies, as well as building resilience through poverty reduction and the strengthening of public services has the potential to reduce the financial and human costs of humanitarian emergencies and to prevent reversing important development gains. However, despite far-reaching recognition of the importance of DRR, international investment in these activities remains low. In 2012, spending on DRR comprised just 6 percent ($630m) of OECD DAC humanitarian assistance.143

Moreover, an estimate from 2011 indicates that OECD DAC donor countries gave only 0.7 percent of non-emergency development assistance for DRR.144 More investment is also needed for poverty reduction and strengthening of public services, given that chronic and extreme poverty is linked to increased vulnerability to disaster145 and countries with strong government institutions tend to be less vulnerable to natural disasters.146

Box 6: Rebuilding schools in Sri Lanka

Students walk through the repaired and rebuilt Shariputra school in Sri Lanka (2007). Photo: Howard Davies/Oxfam GB The Shariputra school in Ahangama, Sri Lanka, was severely damaged by the tsunami. It was one of seven schools rebuilt with funding from Oxfam Novib through its local partner, Educational International. The school‟s 1,340 students (aged 5 to 18) were taught in

temporary UNICEF shelters until the school was finished and fitted with new furniture for the classrooms. The rebuilt school also included a „tsunami wall‟ specifically designed to dissipate the effects of large waves, giving students more time to escape to higher ground.

As the reconstruction neared completion, the school‟s principal, Ruwan Arunashantha Kariyanasam, expressed his satisfaction with the project:

„We are all very pleased with the rebuilding of our school. It has not just been replaced after the tsunami, but greatly improved with many new facilities like special accessible classrooms for students with special needs and a purpose-built library, which we will have completed soon. We also have a new sports and function hall, which we can hire out to the community to raise additional funds for the school... I am looking forward to having the new school completed and the students will have a settled environment to learn in after all the turmoil of recent years.‟

Capacity building and supporting local civil society

A 2008 review of reconstruction in post-tsunami Indonesia and Sri Lanka found that community involvement is essential to building back safer, stronger communities.147 Capacity building and accountability to local communities are internationally recognized priorities, enshrined in the 2005 UN reforms, the IASC‟s Transformative Agenda, and the Good Humanitarian Donorship principles. However, recent evaluations of the humanitarian system have shown that more efforts are needed to ensure that these principles are consistently put into practice.148,149 For example, a recent study found that although there have been efforts to include local and national actors in the response to typhoon Haiyan (one of the strongest tropical cyclones on record which struck the Philippines in 2013), it has still been mostly led, coordinated and implemented by international actors.150

E. CONSIDERATION OF PRE-EXISTING CONFLICTS

While a peace process in Indonesia was already under way prior to the Indian Ocean tsunami, the disaster has often been cited as a catalyst for the end to nearly three decades of sectarian conflict between the government and the Acehnese independence movement, Gerakan Aceh Merdeka (GAM).151 It has been argued that the humanitarian response acted as an incentive for state and local government to cooperate and that the presence of international staff after the tsunami encouraged the emergence of peace, security, and the enforcement of human rights.152 This finding is supported by a 2008 survey, which found that 57 percent of the population in Aceh think that the tsunami, and the response to it, had a positive effect on peace in the region.153

Conversely, in Sri Lanka, which had also suffered from decades of conflict, the response to the tsunami has often been credited with intensifying tensions between the Tamil Tigers and the Sri Lankan government. While the tsunami caused a short-term pause in the civil war, the conflict re-escalated again within a year.154 Not long into the relief effort, complaints emerged that Tamil areas were receiving very little government aid, inciting suspicion about international and civil society organizations.155 As a result of these concerns, an aid-sharing deal was signed between the government and the Tamil Tigers.156 However, this deal ended in November 2005, when a new president was elected.157 Unlike in Indonesia, the conflict in Sri Lanka continued long after the tsunami, until its bloody conclusion in 2009.

Designing conflict-sensitive responses

The TEC joint evaluation contends that any impact the humanitarian response had on the conflicts in Indonesia and Sri Lanka was „serendipitous‟ rather than planned. In general, international agencies engaged in very little „conflict-sensitive‟ programming in Aceh, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. Conflict-sensitive programming is an approach that involves understanding the context in which a humanitarian intervention operates and acting on this understanding to minimize negative impacts.158 The concept of conflict-sensitive approaches lies within the „do no harm‟ edict pioneered in the late 1990s.159 The central premise of „Do No Harm‟ is that aid affects conflicts in one way or another, and, depending on how it is used, has the ability to exacerbate conflicts by increasing divisions between conflicting groups or to strengthen capacities for peace.160

Since the Indian Ocean tsunami, there has been increasing recognition that humanitarian assistance can sometimes exacerbate conflicts. As a result, various resources, working groups, and research studies have been established to better understand and address this problem.161 However, a recent evaluation of the humanitarian system found that there is still a need for humanitarian agencies to devote more effort to understanding the political, ethnic and tribal

Box 7: An evaluation of Oxfam’s response

A 2009 evaluation of Oxfam‟s response highlighted examples of „excellent‟ practice by Oxfam and its partners, but also noted inconsistencies in the quality of housing

construction and livelihood programmes and in the integration of gender and disaster risk reduction into the response.163 A lack of collaboration between different Oxfam affiliates also sometimes affected the quality of programming. The evaluation suggested several strategic and operational methods to improve future responses, such as developing internal minimum standards for humanitarian responses, which have since been introduced.

Oxfam learned many lessons during the tsunami response which have led to changes in the way that the organization works. The tsunami reinforced the need for Oxfam to continue to become more coordinated. There has been significant progress towards this goal, including ongoing streamlining of the work carried out by the different Oxfam affiliates to make emergency responses as effective as possible.

When the tsunami hit, Oxfam was already involved in a review of the organization‟s humanitarian performance and capacity. The tsunami response helped to inform this review and reinforced its importance. The reforms that came out of the review included a new system for categorizing the seriousness of different crises, in order to ensure that they receive the right level of attention, and a conscious decision to focus on the organization‟s areas of expertise, which include providing safe water, sanitation, public health and supporting livelihoods. The 2006 internal Shelter Policy dictates that, while Oxfam should support construction by channelling funds or working with partners, it should not directly engage in construction work.164

5 ONGOING CHALLENGES IN THE FUNDING SYSTEM

‘Those affected by disaster or conflict have a right to life with dignity and, therefore, a right to assistance... All possible steps should be taken to alleviate human suffering arising out of disaster or conflict.’

Sphere Project core beliefs, from the 2011 The Sphere Project Handbook, Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response

The rapid, generous funding that followed the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami highlights the atypical nature of this response. While the tsunami received adequate funding for the relief and recovery effort, many other emergencies do not attract the same level of support. Moreover, the overall level of international funding, even when combined with the domestic response to crises, is only enough to meet a portion of global humanitarian need.

A. CURRENT FUNDING DOES NOT MEET HUMANITARIAN NEED

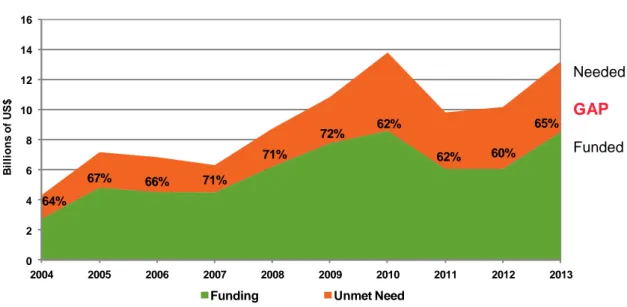

The Global Humanitarian Assistance (GHA) programme has calculated that international humanitarian assistance reached a record $22bn in 2013,165 with an estimated $5.6bn (roughly 25 percent) from private donors.166 However, humanitarian agencies consistently report that funding remains insufficient to meet the level of humanitarian need.167 For example, funding for 2013 UN-coordinated appeals reached $8.5bn, enough to meet only 65 percent of the 13.2bn required (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: The growing funding gap for UN-coordinated appeals (2004–2013)

Source: UN FTS data for all appeals (consolidated, flash, other) accessed 20 October 2014. Adjusted for inflation using annual CPI data from Federal Reserve Economic Data. All values reported in constant 2013 USD.

While donations to UN appeals have dramatically increased over the past decade, the data show that since 2004 funding has continued to hover at approximately 65 percent of identified need. In other words, roughly one-third of humanitarian needs identified in UN-coordinated appeals consistently go unmet. Furthermore, increases in the amounts appealed for have resulted in an increasingly larger funding gap.168 Even after adjusting for inflation, the funding gap for UN

64%

67% 66% 71%

71%

72% 62%

62% 60%

65%

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

Billions of US$

Funding Unmet Need

Needed GAP Funded