Reduction and Elimination in Philosophy and the Sciences

Reduktion und Elimination in Philosophie und den Wissenschaf ten

31. Internationales Wittgenstein Symposium 31

stInternational Wittgenstein Symposium

Kirchberg am Wechsel 10. - 16. August 2008

Beiträge

Papers

31. Internationales Wittgenstein Symposium

Kirchberg am Wechsel 2008

31

31

Reduktion und Elimination in Philosophie und den Wissenschaf ten Reduction and Elimination in Philosophy and the Sciences

31. Internationales Wittgenstein Symposium Kirchberg am Wechsel 2008 Beiträge

Papers

Alexander Hieke Hannes Leitgeb Hrsg.

Co-Bu-08:Co-Bu-07.qxd 28.07.2008 14:37 Seite 1

Reduktion und Elimination in

Philosophie und den Wissenschaften Reduction and Elimination in Philosophy and the Sciences

Beiträge der Österreichischen Ludwig Wittgenstein Gesellschaft Contributions of the Austrian Ludwig Wittgenstein Society

Band XVI

Volume XVI

Reduktion und Elimination in Philosophie und den Wissenschaften

Beiträge des 31. Internationalen Wittgenstein Symposiums

10. – 16. August 2008 Kirchberg am Wechsel

Band XVI

Herausgeber Alexander Hieke Hannes Leitgeb

Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Abteilung Kultur und Wissenschaft des Amtes der NÖ Landesregierung

Kirchberg am Wechsel, 2008

Österreichische Ludwig Wittgenstein Gesellschaft

Reduction and Elimination in Philosophy and the Sciences

Papers of the 31

stInternational Wittgenstein Symposium

August 10 – 16, 2008 Kirchberg am Wechsel

Volume XVI

Editors

Alexander Hieke Hannes Leitgeb

Printed in cooperation with the Department for Culture and Science of the Province of Lower Austria

Kirchberg am Wechsel, 2008

Austrian Ludwig Wittgenstein Society

Distributors

Die Österreichische Ludwig Wittgenstein Gesellschaft The Austrian Ludwig Wittgenstein Society

Markt 63, A-2880 Kirchberg am Wechsel Österreich/Austria

ISSN 1022-3398 All Rights Reserved

Copyright 2007 by the authors

No part of the material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, and informational storage and retrieval systems without written permission from the copyright owner.

Visuelle Gestaltung: Sascha Windholz

Druck: Eigner Druck, A-3040 Neulengbach

Inhalt / Contents

Inhalt / Contents

Formal Mechanisms for Reduction in Science

Terje Aaberge ... 11 Wittgenstein on Counting in Political Economy

Sonja M. Amadae ... 14 Referential Practice and the Lure of Augustinianism

Michael Ashcroft... 17 The Date of Tractatus Beginning

Luciano Bazzocchi ... 20 The Essence (?) of Color, According to Wittgenstein

Ondřej Beran ... 23 Wittgenstein’s Externalism – Getting Semantic Externalism through the Private Language Argument and the Rule-Following Considerations

Cristina Borgoni ... 26 Informal Reduction

E.P. Brandon ... 29 An Anti-Reductionist Argument Based on Spinoza’s Naturalism

Nancy Brenner-Golomb ... 31 Did I Do It? – Yeah, You Did! Wittgenstein & Libet On Free Will

René J. Campis C. / Carlos M. Muñoz S. ... 34 Mental Causation and Physical Causation

Lorenzo Casini ... 38 On Two Recent Defenses of The Simple Conditional Analysis of Disposition-Ascriptions

Kai-Yuan Cheng ... 41 Queen Victoria’s Dying Thoughts

Timothy William Child ... 45 Diagonalization. The Liar Paradox, and the Appendix to Grundgesetze: Volume II

Roy T Cook ... 47 Exorcizing Gettier

Claudio F. Costa ... 50 A Wittgensteinian Approach to Ethical Supervenience

Soroush Dabbagh ... 52 There can be Causal without Ontological Reducibility of Consciousness? Troubles with Searle’s Account of Reduction

Tárik de Athayde Prata ... 55 Algorithms and Ontology

Walter Dean ... 58 The Knower Paradox and the Quantified Logic of Proofs

Walter Dean / Hidenori Kurokawa ... 61 Quine on the Reduction of Meanings

Lieven Decock ... 64 The Scapegoat Theory of Causality

Marcello di Paola ... 67 Logic Must Take Care of Itself

Tamara Dobler ... 70 Wittgenstein on Frazer and Explanation

Keith Dromm ... 73 Dummett on the Origins of Analytical Philosophy

George Duke ... 76

Inhalt / Contents

Wittgenstein meets ÖGS: Wovon man nicht gebärden kann …

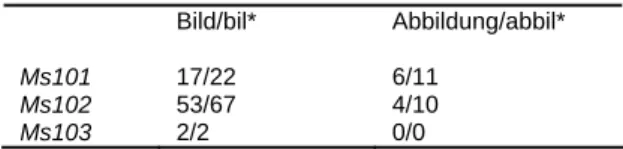

Harald Edelbauer / Raphaela Edelbauer ... 79 Abbildung und lebendes Bild in Tractatus und Nachlass

Christian Erbacher ... 82 Explaining the Brain: Ruthless Reductionism or Multilevel Mechanisms?

Markus Eronen ... 86 Occam’s Razor in the Theory of Theory Assessment

August Fenk ... 89 Die Nichtreduzierbarkeit der klassischen Physik auf quantentheoretische Grundbegriffe

Helmut Fink ... 92 Interpretability Relations of Weak Theories of Truth

Martin Fischer ... 96 Does Bradley’s Regress Support Nominalism?

Wolfgang Freitag ... 99 Zeitliche Ontologie und zeitliche Reduktion

Georg Friedrich ... 103 Why the Phenomenal Concept Strategy Cannot Save Physicalism

Martina Fürst ... 106 Benacerraf and Bad Company (An Attack on Neo-Fregeanism)

Michael Gabbay ... 109 Deflationism and Conservativity: Who did Change the Subject?

Henri Galinon ... 114 Hard Naturalism and its Puzzles

Renia Gasparatou ... 117 The Mind-Body-Problem and Score-Keeping in Language Games

Georg Gasser ... 119 Wright, Wittgenstein und das Fundament des Wissens

Frederik Gierlinger ... 122 Reduction Revisited: The Ontological Level, the Conceptual Level, and the Tenets of Physicalism

Markus Gole ... 125 Reduction and Reductionism in Physics

Rico Gutschmidt ... 128 Physicalism Without the A Priori Passage

Harris Hatziioannou ... 131 Wittgensteins Projektionsmethode als Argument für die transzendentale Deutung des Tractatus

Włodzimierz Heflik ... 134 Rule-Following and the Irreducibility of Intentional States

Antti Heikinheimo ... 138 Relating Theories. Models and Structural Properties in Intertheoretic Reduction

Rafaela Hillerbrand ... 141 The Constitution of Institutions

Frank Hindriks ... 144 Do Brains Think?

Christopher Humphries ... 147 How Metaphors Alter the World-Picture – One Theme in Wittgenstein’s On Certainty

Joose Järvenkylä ... 150 The Modal Supervenience of the Concept of Time

Kasia M. Jaszczolt ... 153 The Determination of Form by Syntactic Employment: a Model and a Difficulty

Colin Johnston ... 156 Zwischen Humes Gesetz und „Sollen impliziert Können“ – Möglichkeiten und Grenzen

empirisch-normativer Zusammenarbeit in der Bioethik (Teil I)

Michael Jungert ... 159 Assessing Humean Supervenience

Amir Karbasizadeh ... 163 Zu Carnaps Definition von ‘Zurückführbarkeit’

Roland Kastler ... 166

Inhalt / Contents

Ding-Ontology of Aristotle vs. Sachverhalt-Ontology of Wittgenstein

Serguei L. Katrechko ... 169 How do Moral Principles Figure in Moral Judgement? A Wittgensteinian Contribution to the Particularism Debate

Matthias Kiesselbach ... 172

“Downward Causation”: Emergent, Reducible or Non-Existent?

Peter P. Kirschenmann ... 175 On Game-theoretic Conceptualizations in Logic

Maciej Tadeusz Kłeczek ... 178 A Metaphysically Moderate Version of Humean Supervenience

Szilárd Koczka ... 181

“In der Frage liegt ein Fehler” – Überlegungen zu Philosophische Untersuchungen (PU) 189A

Wilhelm Krüger ... 184 Problems with Psychophysical Identities

Peter Kügler ... 187 Reducing Complexity in the Social Sciences

Meinard Kuhlmann ... 190 Four Anti-reductionist Dogmas in the Light of Biophysical Micro-Reduction of Mind & Body

Theo A. F. Kuipers ... 193 Two Problems for NonHumean Views of Laws of Nature

Noa Latham ... 196 Some Remarks on Wittgenstein and Type Theory in the Light of Ramsey

Holger Leerhoff ... 199 The Tractatus and the Problem of Universals

Eric Lemaire ... 202 A Critique of the Phenomenal Concept Strategy

Daniel Lim ... 204 Metaphorische Bedeutung als virtus dormitiva

Jakub Mácha ... 207

„Vom Weißdorn und vom Propheten“ – Poetische Kunstwerke und Wittgensteins „Fluß des Lebens“

Annelore Mayer ... 210

„Die Einheit hören“ – Einige Überlegungen zu Ludwig Wittgenstein und Anton Bruckner

Johannes Leopold Mayer ... 213 Counterfactuals, Ontological Commitment and Arithmetic

Paul McCallion ... 216 Getting out from Inside: Why the Closure Principle cannot Support External World Scepticism

Guido Melchior ... 218 Dispensing with Particulars: Understanding Reference Through Anaphora

Peter Meyer ... 221 Reichenbach’s Concept of Logical Analysis of Science and his Lost Battle against Kant

Nikolay Milkov ... 224 Defining Ontological Naturalism

Marcin Miłkowski ... 227 The Logic of Sensorial Propositions

Luca Modenese ... 230 A Wittgensteinian Answer to Strawson’s Descriptive Metaphysics

Karel Mom ... 232 Properties and Reduction between Metaphysics and Physics

Matteo Morganti ... 235 Functional Reduction and the Subset View of Realization

Kevin Morris ... 238 The Writing of Nietzsche and Wittgenstein

Elena Nájera ... 241 Word-Meaning and the Context Principle in the Investigations

Jaime Nester ... 244 Naturalistic Ethics: A Logical Positivistic Approach

Sibel Oktar ... 247

Inhalt / Contents

The Evolution of Morals

Andrew Oldenquist ... 250 Species, Variability, and Integration

Makmiller Pedroso ... 253 Limiting Frequencies in Scientific Reductions

Wolfgang Pietsch ... 256 The Key Problems of KC

Matteo Plebani ... 259 The Metaphysical Relevance of Metric and Hybrid Logic

Martin Pleitz ... 262 Reductionism in Axiology: the Case of Utilitarianism

Dorota Probucka ... 265 The Return of Reductive Physicalism

Panu Raatikainen ... 268 Rethinking the Modal Argument against Nominal Description Theory

Jiří Raclavský ... 271 Different Ways to Follow Rules? The Case of Ethics

Olga Ramírez Calle ... 274 Atypical Rational Agency

Paul Raymont ... 277 Indexwörter und wahrheitskonditionale Semantik

Štefan Riegelnik ... 280 Two Reductions of ‘rule’

Dana Riesenfeld ... 283 Scientific Pragmatic Abstractions

Christian Sachse ... 286 Wittgenstein’s Attitudes

Fabien Schang ... 289 Warum man auf transzendentalphilosophische Argumente nicht verzichten kann

Benedikt Schick ... 292 Making the Mind Higher-Level

Elizabeth Schier ... 295 Zwischen Humes Gesetz und „Sollen impliziert Können“ – Möglichkeiten und Grenzen

empirisch-normativer Zusammenarbeit in der Bioethik (Teil II)

Sebastian Schleidgen ... 298 Mental Causation: A Lesson from Action Theory

Markus Schlosser ... 301 Supervenienz, Zeit und ontologische Abhängigkeit

Pedro Schmechtig ... 304 Reduction, Sets, and Properties

Benjamin Schnieder ... 307 Context-Based Approaches to the Strengthened Liar Problem

Christine Schurz ... 310 The Elimination of Meaning in Computational Theories of Mind

Paul Schweizer ... 313 Following a Philosopher

Murilo Seabra / Marcos Pinheiro ... 316 Davidson on Supervenience

Oron Shagrir ... 318 Supervenience and ‘Should’

Arto Siitonen ... 321 Rule-following as Coordination: A Game-theoretic Approach

Giacomo Sillari ... 325 Science and the Art of Language Maintenance

Deirdre C.P. Smith ... 328 A Division in Mind. The Misconceived Distinction between Psychological and Phenomenal Properties

Matthias Stefan ... 331

Inhalt / Contents

Scepticism, Wittgenstein's Hinge Propositions, and Common Ground

Erik Stei ... 334 Neutral Monism. A Miraculous, Incoherent, and Mislabeled Doctrine?

Leopold Stubenberg ... 337 A somewhat Eliminativist Proposal about Phenomenal Consciousness

Pär Sundström ... 340 Impliziert der intentionale Reduktionismus einen psychologischen Eliminativismus? Fodor und das Problem psychologischer Erklärungen

Thomas Szanto ... 343 Structure of the Paradoxes, Structure of the Theories: A Logical Comparison of Set Theory and Semantics

Giulia Terzian ... 347 The Origins of Wittgenstein’s Phenomenology

James M. Thompson ... 350 Objects of Perception, Objects of Science, and Identity Statements

Pavla Toráčová ... 353 The Reduction of Logic to Structures

Majda Trobok ... 356 Reducing Sets to Modalities

Rafał Urbaniak ... 359 Are Lamarckian Explanations Fully Reducible to Darwinian ones? The Case of “Directed Mutation” in Bacteria

Davide Vecchi ... 362 A Note on Tractatus 5.521

Nuno Venturinha ... 365 The Place of Theory Reduction in the Models of Interdisciplinary Relations

Uwe Voigt ... 368 Ethik als irreduzibles Supervenienzphänomen

Thomas Wachtendorf ... 371 Das ‘schwierige Problem’ des Bewusstseins – oder wie es ist, Person zu sein

Patricia M. Wallusch, Frankfurt am Main, Deutschland ... 374 The Supervenience Argument, Levels, Orders, and Psychophysical Reductions

Sven Walter ... 377 No Bridge within Sight

Daniel Wehinger ... 380 On the Characterization of Objects by the Language of Science

Paul Weingartner ... 383 The Functional Unity of Special Science Kinds

Daniel A. Weiskopf ... 387 Transcendental Philosophy and Mind-Body Reductionism

Christian Helmut Wenzel ... 390 From Topology to Logic. The Neural Reduction of Compositional Representation

Markus Werning ... 393 The Calculus of Inductive Constructions as a Foundation for Semantics

Piotr Wilkin ... 397 The Four-Color Theorem, Testimony and the A Priori

Kai-Yee Wong ... 399 The Comprehension Principle and Arithmetic in Fuzzy Logic

Shunsuke Yatabe ... 402 Intentional Fundamentalism

Petri Ylikoski / Jaakko Kuorikoski ... 405 New Hope for Non-Reductive Physicalism

Julie Yoo ... 408 Are Tractarian Objects Whitehead’s Pure Potentials?

Piotr Żuchowski ... 412

Formal Mechanisms for Reduction in Science Terje Aaberge, Sogndal, Norway

1. Introduction

There is a well known story about Victor Hugo who after having submitted Les miserables to his editor, went on holiday. He was anxious to know about its reception how- ever, and sent the editor a telegram with the single sign

“?”. Shortly thereafter he received the response “!” from the editor (Gion 1989). Clearly both telegrams carried a mean- ing for the receivers. The reason was the existence of the common context determined by the particular situation in which the messages could be interpreted.

The story exemplifies the difference between data and information and how sufficient background knowledge makes it possible to interpret data and turn them into in- formation. The background knowledge defines a context in which to interpret the data. There are two mechanisms for this, either the condition of coherence imposes an interpre- tation or the context already contain definitions of the data.

In any case, the story indicates that if the context is rich then the amount of data needed to describe a state of affairs is smaller than if the context is poor. It thus gives a clue to a preliminary definition of reduction with respect to context: a reduction of a context is an enrichment of the context.

In a formal linguistic setting a context is represented by an ontology, i.e. a set of implicit definitions of the words of the vocabulary used to describe the domain in question.

The ontology provides the formal language with a seman- tic structure that pictures structural properties of its domain of application. The ontology in itself does not furnish the language with a full semantic. It must be supplemented by an interpretation that relates some of terms of the ontology to external ‘objects’, i.e. objects of its domain of applica- tion. The other terms are then given meaning by the defini- tions. A choice of terms whose interpretation is a sufficient basis for the semantic of a language are said to be pri- mary. All the other terms are defined by the primary terms by means of the definitions. The definitions that only con- tain primary terms are called axioms (Blanché 1999). An ontology can thus be considered to be constituted by an axiom system or axiomatic core providing implicit defini- tions of the primary terms and a set of terminological defi- nitions of the additional vocabulary.

An axiom system for the ontology resumes the syn- tactic and semantic information in the ontology. It is mini- mal with respect to both. The syntactic structure repre- sented in the axiom system permits the deduction of all the theorems of the theory and the interpretation of the pri- mary terms gives meaning to the terms introduced by the terminological definitions.

The language is used to describe objects or sys- tems of the domain. The data necessary for a complete description of a system depends on the information con- tent of the axiom system of the ontology. An extension of the system and thus of the ontology provides more infor- mation. Accordingly, an extension of the axiomatic system is a formal expression for reduction.

There are two kinds of reductions, ontological and theoretical reduction. Examples of both will be discussed in the following, however, limited to the case of formal scien-

tific languages. By formal I will mean a language whose syntax is provided by first order predicate logic.

2. Structure of a formal scientific language

Any exposition of the structure of scientific theories is based on a number of distinctions representing ontological commitments. Those I have chosen are partly exhibited in the following figure:

Figure 1

Here Domain W and Domain T stand for two different per- ceptions of reality; the Domain W corresponds to logical atomism and Domain T to the more elaborate set theoreti- cal conception. The Figure 1 does not fully represent the relations between Language and Domain. It must com- plemented by the following diagram,

Figure 2

expressing the two interpretations of the correspondence between the structure of language and the reality: that the structure of reality is projected onto language or that the structure of language is projected onto reality. These inter- pretations are reflected in Wittgenstein’s (Wittgenstein 1961) and Tarski’s (Tarski 1944, 1985) semantic theories respectively: Wittgenstein’s semantic is represented by maps from the domain to language, while the Tarskian semantic is defined by a map from the language to the domain.

In a science there is a need to quantify over sys- tems and properties, however, not both at the same time.

Thus, the a priori second order language is naturally rep- resented by a juxtaposition of two first order languages, the Object Language (OL) and the Property Language (PL). OL serves to give empirical descriptions of the sys- tems of the domain and PL serves to describe the proper- ties of the systems and to formulate models of systems.

Formal Mechanisms for Reduction in Science — Terje Aaberge

They are both endowed with semantic structures defined by ontologies. Their vocabularies consist of the logical constants and three kinds of terms, the names, variables and predicates, each kind having a particular syntactic role. A name refers to a unique system or property, a predicate to a property (predicate of the first kind) or a category of systems or properties (predicate of the second kind), or a relation between systems or properties. A vari- able refers to any of the elements in a given category.

There is no syntactic difference between predicates of the first and second kind; the distinction is semantic. It is based on the ontological distinction between system and properties. A system is observed and thus conceived as a bundle of properties possessed by the system (bundle theory of substance).

The distinction between the two languages captures scientific practises. In OL the systems are directly referred to, while in PL the reference is indirect; it is given by means of identifying properties that are possessed by the system. Thus, while in OL Newton’s second law is ex- pressed by

the acceleration of a body equals the net force act- ing on the body divided by its mass

in PL the same law is represented by the mathematical formula

a = F/m

which is without any explicit reference to the body. “Body”

is not a term in PL. The body in question is implicitly re- ferred to by the mass m that denotes a property of the body (system).

Figure 1 indicates that the set of properties/relations is represented by an abstract property space in the PL. In this language the relation between the property space and the names of the properties are also included. They are represented by maps that simulate the observation of properties. For example, the set of possible locations in real space is represented by the points of abstract three dimensional Euclidean space and the names of the points by their co-ordinates. This relation is formally represented by a map that relates the points of the abstract space with their co-ordinates. The ontology of the property language incorporates these relations. In the property language it is thus also possible to simulate the act of observation.

A model of a system is a representation of the sys- tem in the property language. From the model we can extract a description of the system modelled. The degree of correspondence between the empirical description in the object language and the theoretical description in the property language determines the correctness of the model.

3. Object language and ontological reduction

A domain consists of a set of (physical) systems that pos- sess properties and relations. A system is uniquely identi- fied and described by the properties it possesses. This is done by means of the atomic sentences that attach prop- erties to the system, i.e. they are concatenations of the name of the system and the predicates that refer to the properties of the system. The basis for such a description is logical atomism. Each atomic sentence stands for an atomic fact. The conjunction of atomic sentences that ap- plies to a system provides a description or picture of the

system and serves to distinguish it from the descriptions of other systems.

Some properties are mutually exclusive in the sense that they cannot simultaneously be possessed by a given system; for example, a system cannot at the same time be red and green. This relation of exclusiveness of properties serves to categorise the predicates of the first kind. Each such category is then the range of a map from the set of systems of the domain to the predicates of the first kind.

The map, called an observable, relates systems to the predicates denoting properties. Colour is thus an observ- able. Other examples of observables are form, tempera- ture, position in space, mass, velocity etc.

One distinguishes between two kinds of observables referring to two kinds of properties, properties that do not change in time and thus serves to identify the system, and properties that change. The corresponding observables are identification and state observables respectively. The state properties form a space called the state space of the systems.

The systems can be classified with respect to the identification observables. One starts with one of the ob- servables and uses its values to distinguish between the systems to construct classes. Thus, one gets a class for each value of the observable, the class of systems that possess the particular property, e.g. the class of all red systems, the class of all green systems etc. The procedure can be continued recursively until the set of identification observables is exhausted. The result is a hierarchy of classes with respect to the set inclusion relation. The basic entities of the classification are the elements of the leaf classes. The discovery of new independent observables will then lead to a refined classification and create new leaf classes and thus new classes of basic entities.

The classes are referred to by predicates of the second kind which thus are ordered naturally in a taxon- omy that constitute a linguistic representation of the classi- fication. The taxonomy together with the definitions of the classes is an ontology for the object language. The class definitions impose a semantic structure that mirrors the class inclusion relations and create semantic relations between the predicates. An extension of an ontology due to a refined classification is thus an example of an onto- logical reduction. Moreover, the domain of application of the new language is extended to incorporate the new sys- tems to which some properties of the old systems can be referred. The axiom system for the ontology is given by the definitions of the leaf classes.

An example of a classification is that of material substances. They can be classified in terms of their chemi- cal properties. In particular, the pure chemical elements are given by the periodic table. Taking into account the physical properties however, we get a refined classification distinguishing between isotopes of the same kinds of at- oms.

The classification hierarchy can be given a mereological interpretation, i.e. the elements of the differ- ent classes may be identified by their composition in terms of elementary constituents (Smith et al. 1994). The pas- sage from one level of granularity in terms of elementary constituents to a finer one which in the example above going from the atoms of the periodic table to the constitu- ents of atoms (electrons, protons and neutrons) is an ex- ample of ontological reduction.

Formal Mechanisms for Reduction in Science — Terje Aaberge

4. Property language and theoretical reduction

Physics offers many examples of theoretical reduction. We will consider one from classical mechanics. It has several equivalent formulations of which we will discuss two, the Newtonian and Hamiltonian mechanics.

The structure of Newtonian mechanics is defined by a set of axioms covering

Euclidean space and time (abstract) Action of the Galilei group

Operational definitions of velocity, length and time measures determining coordinatisations

Calculus

Newton’s second and third laws

The set of axioms supplemented with terminological defini- tions constitute an ontology for the property language of Newtonian mechanics.

A model is defined by the specification of a set of equations, the equations of motion. The equations of mo- tion implement Newton’s second law and include quanti- ties representing the identification properties of the system modelled and empirical constants, i.e. the masses of the objects and the gravitational constant. The solutions, moreover, depend on another set of empirical quantities defining initial conditions.

Hamiltonian mechanics is a formulation of classical mechanics that is a more restrictive way of looking at clas- sical mechanics. It is based on the following elements

Phase space and time as a differential manifold Action of Galilei group

Operational definitions of momentum, length and time determining coordinatisations

Hamilton’s principle of least action

The set of axioms supplemented with terminological defini- tions constitute an ontology for the property language of Hamiltonian mechanics.

A model of a system is defined by a function on phase space, the Hamiltonian, which includes reference to identification properties of the system modelled. Given the Hamiltonian, the equations of motion are derived from the hypothesis that the dynamics satisfies Hamilton’s principle.

The passage from Newtonian mechanics to Hamil- tonian mechanics is a theoretical reduction; the axioms of Hamiltonian mechanics impose more structure than those of Newtonian mechanics but at the same time they define a more restrictive theory. The definition of a model is thus more compressed in Hamiltonian mechanics than in New- tonian mechanics. In fact, while the definition of a model of a simple system needs the specification of three functions, the force, in Newtonian mechanics, it is defined by only one function, the energy, in Hamiltonian mechanics. The domain of application of Hamiltonian mechanics is how- ever, smaller than that of Newtonian mechanics. In fact, while Newtonian mechanics can model dissipative sys- tems, Hamiltonian mechanics can only handle conserva- tive systems.

It should be noticed that the terms reduction is also used to denote the limit of physical theories for parameters going to zero.

Literature

Blanché, Robert 1999: L’axiomatique. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France

Gion, Emmanuel 1989 Invitation à la theorie de l’informatique, Paris: Éditions du Seuil

Smith, Barry and Casati, Roberto 1994 Naive Physics: An Essay in Ontology, Philosophical Psychology, 7/2, pp. 225-244.

Tarski, Alfred 1985 Logic, Semantic, Metamatematics (second edition), Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company

Tarski, Alfred 1944 The Semantic Conception of Truth and the Foundations of Semantic. Philosophy and Phenomenological Re- search 4, pp. 341-375

Wittgenstein, Ludwig 1961: Tractatus logico-philosophicus, Lon- don: Routledge and Kegan Paul

Wittgenstein on Counting in Political Economy Sonja M. Amadae, Columbus, Ohio, USA

This paper follows Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics to investigate the source of the purported necessity delineated in mathematical statements and proofs. It suggests that this “normativity”

has a similar structure to that underlying promising, contracting, and political obligation. Whereas many philosophers have abdicated the project of defending that empirical science can yield necessary truths or universal laws,1 still it is typical that mathematical truths are conceived to be necessary. Therefore the philosopher W.V.O. Quine, although a thorough-going empiricist who attempted to defend mathematics on the grounds of sensory perception, still faced the burden of explaining

“why mathematics was (and is) thought to be necessary, certain, and knowable a priori.”2 If we understand

“normativity” to convey some sort of structural indispensability that may guide judgment and action, then mathematical knowledge represents perhaps the paradigmatic case of a codified, law-like system that embodies non-negotiable relations and claims, that may be intuited by the human intellect.

There is an arresting debate at the foundations of mathematics over whether mathematical objects, or numbers, have an objective existence independent from the mind. To simplify various positions on this question into two varieties, on the one hand are the “realists,” who hold that the truth of mathematical statements is externally determinate, even if its status is undecidable within a set theoretic or formal system: “We employ such a conception if we hold that the statement may be determinate in truth- value irrespective of whether we can recognize what its truth-value is.”3

A second school of mathematics, referred to as anti- realism or intuitionism, accepts that mathematical truths exist only in the mind of mathematicians: they are constructed. Such an acceptance of the imaginative work done by mathematicians would seem to be on par with Wittgenstein’s emphasis of the social character of the normativities of counting, calculating, and proving.

“Wittgenstein’s general treatment of the topic of rule- following entails that the status of a proof, or calculation, is always in need of ratification.”4 By this account, human counting practices retain their shape, or consistent patterns, over time not because they are laid down by iron- clad procedural rules, but because we commit ourselves to interpreting and acting on the rules as consistently as our contingent intersubjective context makes possible.

This lack of agreement about the foundation of mathematics, over whether the objects of its investigation actually exist or not, stands in parallel to debates over whether moral systems represent truths independent from

1 For example, W.V.O. Quine, for discussion see Shapiro, Thinking About Mathematics, 218,

2 Shapiro, Thinking About Mathematics, 218.

3 Crispin Wright, Wittgenstein on the Foundations of Mathematics (Cam- bridge: Harvard University Press, 1980), 7; even philosophers of mathematics who hold a naturalistic position that ultimately mathematics should be verifia- ble through scientific (empirical) means, endorses numeric realism: “As a realist [P.] Maddy (1990: cha. 4, ss 5) agrees with Gödel that every unambi- guous sentence of set theory has an objective truth-value even if the sentence is not decided by the accepted set theories” (Shapiro, 224).

4 Wright, Wittgenstein, 128.

the cultures in which they are expressed. There is a symmetry between the assertion of the existence of deontological moral truths, such as the Kantian categorical imperative, and the claim of independent validity of mathematical truths; either case, so far as we know, cannot in principle confirm its verification-transcendent authority. Even if this parallel is striking, it is further apparent that whereas deontology in morals is a position marginalized by mainstream scientific approaches to human behavior, 5 realism in mathematics is the more widely accepted status quo in philosophies of science and math.6 This realism essentially accepts that humans have

“the capacity to grasp a verification-transcendent notion of truth”7 in matters of mathematics, but doubts the same in matters of morals or ethics. We routinely accept verification-transcendence in mathematics but not in ethics.

Granted this general privileging of the normativity of mathematics as evincing necessary, a priori, yet verification independent, truths, a philosophy of mathematics is called upon to “account for the at least apparent necessity and priority of mathematic[al knowledge].”8 Indeed, it seems that much of the present- day celebration of scientific naturalism, that casts doubt on the reality of moral and ethical judgment, strives to present a position on mathematics that navigates the notoriously unbridgeable chasm between a priori and a posteriori knowledge. Quine, Hilary Putnam and P. Maddy are leading philosophers who have attempted this line of argumentation, ultimately seeking to preserve the nonnegotiable quality of math while grounding it on knowledge derivable from empirical observation.9 However, this line of inquiry consistently concedes both that empiricism is irrelevant for the actual practice of mathematics, and that mathematical truth is independent from our procedures of knowing it.10 Rather, it suggests that mathematics will finally be vindicated in scientific application.11 Conveniently, Wittgenstein presents an anti- realist philosophy of math, consistent with intuitionism in many of its details and implications, but with the added benefit of not advocating any need to revise mathematical practice.

In exploring the character of mathematics as a language game that perhaps best represents our paradigmatic case of “rule-following,” Wittgenstein suggests that the laws of mathematics stand as imperatives and commands, and not as objectively verifiable truth claims: “Mathematical discourse is not fact- stating; its role is rather to regulate forms of linguistic practice.”12 If we distance our understanding of the source of mathematical normativity as flowing from objective objects and relations that exist outside our minds and practices, then we may understand that mathematical statements have the character of declarations,

5 Jean Hampton, The Authority of Reason (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

6 Shapiro, Thinking about Mathematics, “Numbers Exist,” 201-225.

7 Wright, Wittgenstein, 10.

8 Shapiro, Thinking About Mathematics, 23.

9 See Shapiro, Thinking About Mathematics, “Numbers Exist,” 201-225.

10 Shapiro, 220, 224.

11 Shapiro, 220.

12 Wright, Wittgenstein, 157.

Wittgenstein on Counting in Political Economy — Sonja M. Amadae

imperatives, or commands in the form of admonishing adherence to rules that we assent to follow. The intuitionist Dummett, whose position Wittgenstein’s resembles, refers to mathematical statements as quasi-assertions:

Quasi-assertions are declarative sentences which are not associated with determinate conditions of truth and falsity but share with assertions properly so-called the feature that there is such a thing as assenting to them; where such assent is

communally understood as a commitment to some definite type of linguistic or non-linguistic conduct, and receives explicit expression precisely by the making of the quasi-assertion.13

The subtle aspect of understanding the distinction between mathematical statements as in principle verifiable against an objective reality, versus having the character of being ratified by voluntarily acceptance, is that although we seek to preserve some sense of non-arbitrary structure, we must locate its apparent “necessity” in our discretionary compliance rather than in some facet of extra-mental reality. This necessity has the form of willingly binding ourselves to a normative correctness that we enact in our practice. Hence we have the sufficient leverage to not only ask “[o]f someone who is trained [in a specific type of rule- following] ‘How will he interpret the rule in this case?’”, but further to raise the question, “How ought he to interpret the rule for this case”?14

This view of mathematics as having a humanly devised command structure instead of a structure insured by objective reality alters our picture of the type of normative guidance underlying mathematical judgment.

Instead of being guided in making mathematical statements by facts, we consider that “all mathematical propositions [are] expressed in the imperative, e.g., ‘Let 10 x 10 be 100.’”15 The significance is that this depiction of mathematics makes the consistency of its structure dependent on our voluntary commitment to uphold conceptual relations in specific ways:

Such an account is exactly what we should intuitively propose for sentences expressing the making of a promise. No one would ordinarily suppose that the use of sentences of the form, ‘I promise to …’ is best understood as the making of a statement, true or false; though their being prefixed by ‘it is true that …’ is grammatical sense.16

The promissory quality, then, of mathematical normativity is that mathematical rules suggest what we “ought to conclude,” and in participating in these rule-following exercises we accede to draw the conclusion implied by the rule. It is not that some feature of an objective world of numbers intercedes to form the basis of our judgment in a necessary fashion. Rather, in mathematical rule-following, we agree to abide by the rules as prefiguring or commanding our judgment. If we consider the role proofs play in mathematics, “it marks not a discovery of certain objective liaisons between concepts, but something more like a resolution on our part so to involve them in the future.”17

13 Wright, Wittgenstein, 155.

14 Ludwig Wittgenstein, Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics, ed. by G.H. von Wright, R. Rhees, and G.E.M. Anscombe, trans. By G.E.M. Ans- combe (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996) (RFM), V-9, p. 267.

15 Wittgenstein, RFM, 155.

15 Ludwig Wittgenstein, RFM, V-17, p. 276.

16 Wright, Wittgenstein, 157.

17 Wright, Wittgenstein, 135.

If our understanding of the normativity structuring apparently necessary truths in mathematics rests on our commitment to follow the rules of mathematics, then it is possible to see that the rule-following nature of math is little different from other rule-following institutions throughout our society. This opens the possibility of considering that social-norms that stand as a system of rules have as much sanctity as do the rules of mathematics. Typically, social norms are regarded as subject to preference; either an individual prefers to follow a social norm or not; if she chooses to follow a social norm, this is because she prefers to do so. However, in the case of mathematical judgment, preference is seldom invoked as a source of decision over the result of a calculation or proof.

This recasting of the foundation, as it were, of mathematics from fact and objective truth to socially constructed and ratified laws suggests the possibility for drawing a parallel between legal systems of rule-following and mathematical systems. In his essay, “The Groundless Normativity of Instrumental Rationality,” Donald Hubin argues that neo-Humean instrumentalists “must engage in the same ‘lowering of expectations’ [of the source of normativity of instrumental rationality to the same level]

that the legal positivist must.”18 For Hubin, practical rationality, of which instrumentality is part, is not an objective matter. In making his point, he draws on legal positivism’s retreat from natural law theory, and draws on H.L.A. Hart to expand on this view. 19 Hubin is making the point that even though a legal system provides a normative basis for action, it cannot ground its ultimate principles. I am reworking Hubin’s parallel between positive law and instrumental reason to contrast a realist account of math with an alternative declarative understanding. In an anti-realist mathematics, the binding quality of rules only holds insofar as we assent to them.

It has traditionally been the case the social and political normativity has been viewed as of a lesser pedigree than instrumental and mathematical normativity insofar as the former is conditional, and the latter is non- negotiable. For example, Phillip Pettit provides an explanation for how social norms may be derived from instrumental agency as the former is conditional on individual rational self interest.20 In his Theory of Justice, John Rawls was widely criticized from within rational choice theory for placing action according the “the reasonable,” which included the political theoretic concept of fair play, on par with agency conforming to the dictates of expected utility theory.21 It was not automatically obvious from within rational choice theory that agents had a duty to uphold the rules of government if they did not further an agent’s ends in each and every circumstance of action.22 Therefore, without some sanctioning device that alters payoffs, the rule of law does not in and of itself provide a reason for action that trumps agents’

preferences over end states. Rawls concludes of his contrasting approach to justice as fairness, “There is no thought of trying to derive the content of justice within a

18 Donald Hubin, "The Groundless Normativity of Instrumental Rationality", The Journal of Philosophy 98:9(2001), 445-468, 466.

19 Hubin, “Groundless Normativity,” 463.

20 Philip Pettit, “Virtus normativa: Rational Choice Perspectives,” in his Rules, Reasons, and Norms (Oxford University Press, 2002), 308-343.

21 John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (Harvard University Press, 1971); John Rawls, “Justice as Fairness: Political not Metaphysical,” Philosophy and Public Affairs, 14:3 (summer, 1985), 223-51.

22 This is the problem David Gauthier faces in Morals by Agreement (Oxford University Press, 1985).

Wittgenstein on Counting in Political Economy — Sonja M. Amadae

framework that uses an idea of the rational as the sole normative idea.”23

I am suggesting that mathematics, in any form, but even more specifically as it is harnessed to anchor all manners of institutions in political economy that depend on

“accurate counting” for their functioning, embodies the normativity of Rawls’ “reasonable” as opposed to the rational.24 By Rawls’ description, “if the participants in a practice accept its rules as fair, and so have no complaint to ledge against it, there arises a prima facie duty…of the parties to each other to act in accordance with the practice when it falls upon them to comply.”25 Most of us accept the normativity of mathematical rule-following automatically out of habit or a sense of duty. We do not at first perceive that this virtually innate compliance cuts across the grain of the competing, and supposedly more basic, normativity of instrumental agency which recommends counting in one’s favor when one can get away with it. In fact, considerations of expected utility do interrupt counting

23 Rawls, “Justice as Fairness,” 237.

24 For a discussion of the distinction between the rational and the reasonable in Rawls, see Rawls’ “Justice as Fairness,” and S.M. Amadae, Rationalizing Capitalist Democracy (Chicago University Press, 2003), 271-3.

25 Rawls, “Justice as Fairness,” 60.

practices in cases of embezzlement, fraud, bribery, and ballot box stuffing. The normativity of counting and calculating represents the logic of appropriateness and not the logic of consequences. Adherence to mathematical rules confines judgment; judgment is not a function of preferences over outcomes.

Counting practices throughout political economy resemble the rule of law insofar as they do not have an independent object or autonomous truth-value separate from the rules constituting them. Although most of us do not actually determine, or even consent to, the rules governing these procedures in banking, insurance, taxation, inheritance, or elections, still there is an evident presumption that one counts in accordance to the rules free from considerations of our obvious interest in the outcomes. Much like Rawls’ formulation of “the Reasonable,” most of us have been conditioned to accept, or even to reflexively consent to, an inherent necessity of counting in accordance with the rules directing the activity.

Referential Practice and the Lure of Augustinianism Michael Ashcroft, Melbourne, Australia

This paper is an examination and defence of Wittgenstein's thesis that language itself promotes an Augustinian picture of its workings. Let us define Augustinianism as the thesis that the meaning of an expression is its referent, and distinguish a strong variant that restricts the referents of expressions to ostensively indicatable material objects. In this paper I will argue that if Wittgenstein is correct about reference talk, linguistic practice tempts us to (incorrectly) adopt both positions. I shall begin by describing a naïve notion of reference. Then I will examine the role of reference in contemporary meaning theories and draw parallels with Wittgenstein's own account in order to elucidate the latter. Finally I will explain why the resulting practices can lead us to accept both forms of Augustinianism, and why these positions are mistaken.

At first blush, Wittgenstein's ‘meaning is use’ thesis seems to offer a simple account of reference. As he noted at PI 10:

What is supposed to shew what [words] signify, if not the kind of use they have?

I take Wittgenstein to accept that, in one sense of ‘refers’

or ‘signifies’, the referential link between a sign and its referent lies in the fact that the rules for some signs use are such that their correct use intimately involves (a) par- ticular ostensively indicatable material entity/entities which are thereby the referent(s) of the sign. It is this sense that captures what I shall term ‘naïve referential practice’.

But, Wittgenstein points out, it is not this sense of reference that motivates the question of what the expressions of his simple language refer to. Since he had explained the use of the expressions he was at that point dealing with, in its naïve sense the question is already answered. Thus, Wittgenstein continues, the question must be a request ‘for the expression “This word signifies this” to be made part of the description’ of the expressions use. There must, alongside our naïve referential talk, be a sophisticated variant wherein the uses of expressions are explicated via referential claims. Certainly, even in ordinary language, ‘refers’ has a much broader role than the naïve practice allows. We talk of our expressions referring to abstract objects like numbers, fictional objects like Sherlock Holmes, properties like blue, and many other things besides. The only hypothesis here seems to be that this broader use of ‘refers’ is involved in elucidating the use of expressions. For the purposes of this paper I shall assume this is correct. For what I wish to argue is that it is the way Wittgenstein believed that expressions such as

‘This word signifies this’ and ‘This word refers to this’ are made part of the description of words’ uses that leads to the conclusion that language itself tempts us to understand it in an Augustinian fashion.

To explain this, let us begin by turning to the role of reference in formal meaning theories. Presuming a Fregean syntax and ignoring complications required to deal with quantifiers, a typical meaning theory attributes semantic values to names and treats predicates as functions from names to the semantic value of sentences – where an expression’s semantic value is that which indicates the contribution the expressions make to the meanings of the sentences it can be part of, whilst a

sentence’s semantic value is its meaning. The theory then gives a functional account of the logical connectives which permits the production of semantic values for complex sentences, and lastly (and most problematically) provides a theory for how the use of sentences can be deduced from the semantic values the meaning theory attributes to them. In attributing semantic values to (the sub-sentential expressions the theory parses as) names, the names are said to refer to objects, which, in a deliberately set- theoretic construal of what is going on, we can take to be grouped in the meaning-theory’s domain. The theoretical relation of reference thus introduced can be expanded such that one might also say that definite descriptions and predicates refer to the objects that satisfy them and (possibly empty) sets of objects respectively. The latter case looks very akin to saying that predicates refer to properties, and to assist this exposition let us explicitly accept that properties are sets. In this case, a set-theoretic construal of the quantifiers permits us to understand them as referring to properties (sets) of sets – taking ‘all’ to refer to the property of being identical to the universal set and

‘some’ the property of not being identical to the empty set.

Importantly, the single criterion for a successful meaning theory (as a descriptive account of the meanings we do attribute to others) lies in its getting its theorems correct. In the rarefied air of theoretical semiotics, it makes no sense, Davidson pointed out, to complain that a meaning theory comes up with the right theorems time after time, but has the logical form (or deep structure) wrong. [Davidson;

1977] The objects to which an expression refers are therefore not something that can be examined directly, but are determined by the legitimacy of the theorems the referential axioms produce.

One might object that referential axioms are not so thoroughly unconstrained, for they relate singular terms to objects. Therefore only those things that actually exist are kosher referents in the theory. So, for example, since there is no object Atlantis, a meaning theory ought not to accept the axiom ‘‘Atlantis’ refers to Atlantis’. One might reply that by the criterion given above what is important is merely that the meaning theory produces the correct theorems.

So whilst one could, there is neither need nor justification in restricting the axioms of a meaning theory such that one ought to include as referents only objects one is ontologically committed to. But this reply is too quick. For the objection’s motivation is likely not the given criterion for determining a correct meaning theory, but Quine’s thought that accepting any theory requires ontological commitment to the objects it quantifies over (or, since a theory may be satisfied by models with different domains, it requires existential ontological commitment to there being one such domain). Insofar as, for any singular term of a theory, t, the theory implies (∃x)(x=t), a theory’s singular terms refer to objects of its domain of quantification – to objects which we therefore ought to be ontological committed.

There are reasons to object to this claim. But I shall not pursue them here. Let us accept that a theory requires ontological commitment to the objects its quantifiers range over. In the case of a meaning theory, these objects are the semantic values of (expressions parsed as) names.

But these objects have not been shown to be the middle- sized dry goods we would, in the aforementioned naïve reference talk, say are the referents of most of the

Referential Practice and the Lure of Augustinianism — Michael Ashcroft

mentioned expressions in the referential axioms. On the contrary, formal semantics is a mathematical discipline:

First order set theory. Given the possibility of a set- theoretic construal of formal meaning theories, as well as their historical development from Tarskian model theory, we might think the same is true in their case; or more weakly, we might think it possible to interpret them in this way. If so, then although we owe ontological commitment to the members of a meaning theory’s domain, these would, or at least could, be urelements. In which case the axiom ‘‘Atlantis’ refers to Atlantis’ demands ontological commitment to nothing more than an (existent) urelement, not a (non-existent) continent.

This foray into formal meaning theories casts light on how the expression “This word signifies this” can be made part of the description’ of the word’s use. As in formal meaning theories, so in folk practice: It occurs through reference talk coming to be used to indicate at least certain aspects of the expression’s semantic role.

This indication can be wider or narrower. We have, for example, numerals in our language that are characterised as referring to natural numbers. They are characterised this way both en masse, in that referring to natural numbers is what numerals do, and individually, in that each numeral has a specific natural number it refers to.

Presuming the practice does not also describe complex arithmetical equations as referring to numbers (or numbers alone), to say that a person uses a particular expression to refer to a natural number is to indicate that they mean it as a numeral. To indicate that they use it to refer to a particular natural number is to indicate that they give it the same meaning as a particular numeral. Let us assume, as seems plausible, that natural language has the semantic vocabulary – expressions denoting the categories of objects, properties, relations, truth functions, properties of properties, etc, and the means to provide indefinitely many names of the individuals entities of the various categories – to allow us to think of every sub-sentential expression (as parsed in the canonical syntax, which we can assume to be Fregean) as referring to particular referents of a particular category. Let us call these the canonical referents of the language's sub-sentential expressions.

This permits information about the meaning a person gives a sub-sentential expression to be expressed by the class of entity that the expression is said to refer to: to learn that someone uses a sub-sentential expression to refer to an object is to discover that they mean it as a name (or definite description), whilst to learn they use it to refer to a property is to find they mean it as a predicate, etc.

Referents, via the referential relation, provide a model for language on the basis of referential claims of the form ‘‘a’

refers to b’ and ‘There is some x such that ‘A’ refers to an x’. To those familiar with the practice, this model categorises the correct use of expressions. Explaining the model a person utilises helps explain the meaning they provide their expressions. Telling others the model they ought to use helps to teach them to use language as we wish them too. Since such a model provides referents that suffice, within the practice, to entirely represent the contribution the expressions make to the meanings of the sentences they can be part of, then knowledge about what a person refers to by an expression will provide knowledge of what the person means by the expression.

It is but a short step from believing our language and canonical syntax permits such a referential practice to thinking we possess the same. Such a sophisticated referential practice would not be redundant. As well as facilitating learning, it permits translations from one language to another; indeed it permits extremely subtle translations that can elucidate the similarities and differences in structures between the two languages (cf PI 10). But when applied to one’s own language in the presence of competent users the practice idles, it produces trivial substitution instances of the schema ‘‘A’ refers to A’, or ''A' refers to the property (of) A', etc (perhaps with small amounts of declination or conjugation to produce appropriately reified canonical referents). This is harmless enough, but note that reference is simultaneously important in elucidating meaning and every expression is (given a recursive categorisation system and an ability to provide names for previously undiscussed members of categories) tautologically provided with a referent, and this referent is (also tautologically) the meaning (semantic role) of the expression.

Thus, as in formal meaning theories, saying that an expression possesses a particular referent, or possesses a referent of a particular type, provides information about the expressions’ semantic value. (And certainly, Wittgenstein exorcises any concern about the legitimacy of the used expressions on the right of reference claims. We can think of this sophisticated reference talk as a sui generis linguistic practice whose utility lies in its creation of this referential model. The objects of this model, which we arguably need to be ontologically committed to, are nothing more than other expressions of the language.) Such, I think, is Wittgenstein’s understanding of how expressions such as ‘This word refers to this’ are made part of the description of the use of words.

It is clear how such a linguistic practice lures us towards Augustinianism. For in the sophisticated practice every expression possesses a referent which is, in some sense, the expressions meaning (semantic role). Two points elucidate the lure and problems of the weak and strong Augustinian accounts respectively:

(i) Within sophisticated referential practice, refer- ence talk provides a model of the semantic role of expressions in that referential claims repre- sent, to those familiar with the practice, the se- mantic role of expressions. It is a mistake to think that the possession of a referent in this sense causes an expression to have a seman- tic role.

(ii) Within sophisticated referential practice, all ex- pressions possess (their canonical) referents which represent their semantic role. But, as noted, we also naïvely talk about expressions referring in the sense that their correct use inti- mately involve (a) particular material entity/

entities which are thereby their referent(s). It is a mistake to think that the fact that all expres- sions possess referents in the sophisticated sense entails that they possess referents in the naïve sense. It is likewise a mistake to think that the referents expressions may possess in the naive sense represent the semantic role of the expression.

Referential Practice and the Lure of Augustinianism — Michael Ashcroft

The Augustinian account confuses modelling with explain- ing and, in its strong variety, conflates the naïve concept of reference with the sophisticated. But the ease of these mistakes is why Wittgenstein felt that, given a sophisti- cated referential practice, our language itself attempts to foist an Augustinian understanding upon us. In searching for what Wittgenstein described as the 'life' of our expres- sions we immediately confront a picture of meaning pro- vided by a practice wherein the semantic role of expres- sions is given by their referents. To paraphrase his charac- terisation, this picture holds us captive. We cannot get outside it, for it lies in our language and languages repeats it to us inexorably. But we can equally see why the Augus- tinian accounts are mistaken, confusing modelling with explanation and, in the strong case, trading on ambiguity.

Literature

Davidson, Donald, “Reality without reference”, (1977) in his Inquir- ies into Truth and Interpretation, Oxford University Press, 1984, p.

223

Wittgenstein, Ludwig, Philosophical Invesstigations, Basil Black- well, Oxford, 1963