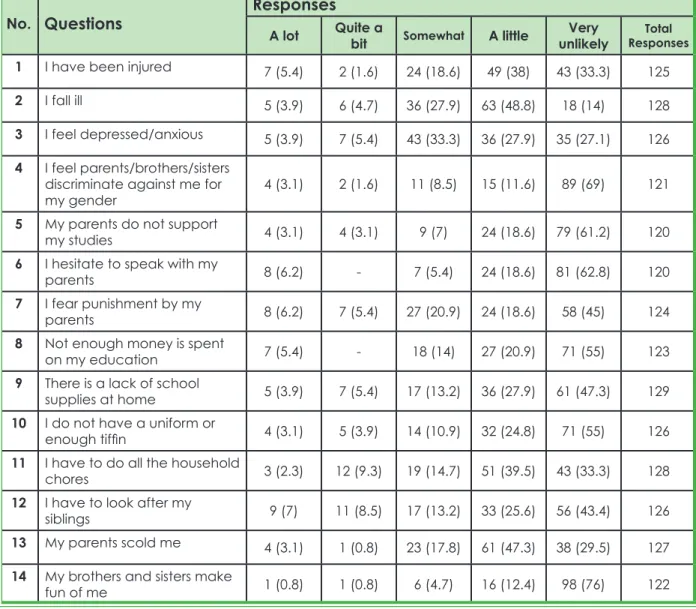

The Educational Resilience of Children in Urban Squatter Settlements of Kathmandu

Volltext

Abbildung

ÄHNLICHE DOKUMENTE

The purpose was to give an overview of the oral health status of Ghanaian pre-school and school-aged children in rural and urban areas between the ages of 3 and 12 years in the

The research reported in this thesis has been motivated by the clinical professional and personal experience of the author in Mumbai, focussing the work on particular themes

In terms of studying riskscapes this means to focus on particular relations that constitute the riskscape – in this case urban rivers that relate people and places fluvially –

Here we studied how commonly used regression models can be applied in the analysis of environmental thresholds. The change of landscape patterns from 2000 to 2008 were analyzed

By 2030, urban areas are projected to house 60 per cent of people globally and one in every three people will live in cities with at least half a million inhabitants..

In December 2012, the Israeli government announced that it had authorised the construction of some 3000 new housing units in the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem?. This was

Mothers of adolescents had significantly more children than mothers of pre-school children (Table 8). This cohort effect can be attributed to the fact that most

The extent of cumulative adverse childhood experiences such as war, family violence, child labor, and poverty were assessed in a sample of school children (122 girls, 165 boys)