- 1

OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools

Country Background Report for Austria

Prepared by

Michael Bruneforth, Bernhard Chabera, Stefan Vogtenhuber, Lorenz Lassnigg

Autumn 2015

This report was prepared by the Ministry of Education and Women’s Affairs (BMBF), the Federal Institute for Educational Research, Innovation & Development of the Austrian School System (BIFIE) and the Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS) as an input to the OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools. The OECD and the European Commission (EC) have established a partnership for the project, whereby participation costs of countries which are part of the European Union’s Erasmus+ programme are partly covered.

The participation of Austria was organised with the support of the EC in the context of this partnership. The report responds to guidelines the OECD provided to all countries and it aimed to prepare for the country visit of the OECD review team to Austria in June 2015. The opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the national authority, the OECD or its member countries. Further information about the OECD Review is available at www.oecd.org/edu/school/schoolresourcesreview.htm.

The published version of the country background report entails a number of editorial changes. The page numbers given in the reference “Bruneforth et al., forthcoming” in the country review reportNusche, D., T. Radinger, M. R.

Busemeyer, H. Theisens (2016), OECD Reviews of School Resources: Austria 2016, OECD Reviews of School Resources, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264256729-en, therefore, do not necessarily match the pages in the published version of the background report.

- 2

- 3

Table of Contents

Table of Contents ... 3

Executive Summary... 6

ABBREVIATIONS ... 9

Schools and Programmes ... 9

Selected federal laws – translation and online sources ... 9

Other abbreviations ... 10

Naming of governmental levels ... 11

Purpose and scope of this report ... 12

Chapter 1: The national context... 14

1.1 The economic and social context ... 14

1.2 Demographic developments ... 14

1.3 Political context ... 17

1.4 Public sector management ... 22

Chapter 2: The school system ... 26

2.1 Organisation of the school system ... 26

2.1A Recent and ongoing reforms to the organisation of schools ... 31

2.2 Education environment ... 34

2.3 Objectives of the education system and student learning objectives ... 36

2.4 Distribution of responsibilities within the school system ... 36

2.5 Market mechanisms in the school system ... 42

2.6 Performance of the school system ... 43

2.7 Policy approaches to equity in education ... 48

2.8 Main challenges ... 50

Chapter 3: Governance of resource use in schools ... 57

3.1 Level of resources and policy concerns ... 57

3.2 Sources of revenue ... 63

3.3 Planning of resource use ... 66

3.4 Implementation of policies to improve the effectiveness of resource use ... 70

3.5 Main challenges ... 71

Chapter 4: Resource distribution ... 74

4.1 Distribution of resources between levels of the education administration ... 74

4.2 Distribution of financial resources across resource types ... 75

4.3 Distribution of resources between levels and sectors of the school system ... 77

4.4. Distribution of resources across individual schools ... 78

4.5 Distribution of school facilities and materials ... 81

4.6 Distribution of teacher resources ... 87

4.7 Distribution of school leadership resources ... 91

4.8 Main challenges ... 93

Chapter 5: Resource utilisation ... 95

5.1 Matching resources to individual student learning needs ... 95

5.2 Organisation of student learning time ... 98

5.3 Allocation of teacher resources to students ... 101

5.3a Organisation of the teachers’ work ... 109

- 4

5.3b Support staff in schools ... 113

5.4 Organisation of school leadership ... 114

5.5 Teaching and learning environment within school ... 115

5.6 Use of school facilities and materials ... 118

5.7 Organisation of education governance ... 118

5.8 Main challenges ... 122

Chapter 6: Resource management ... 124

6.1 Capacity building for resource management ... 124

6.2 Monitoring of resource use ... 124

6.3 Transparency and reporting ... 125

6.4 Incentives for the effective use of resources ... 125

6.5 Main challenges ... 126

Reference list ... 128

Table of Figures ... 135

Table of Tables ... 136

- 5

- 6

Executive Summary

This Country Background Report has been developed to prepare the OECD ‘Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools’ in Austria. It describes the legislation and governance structures as well as common practice of the administration and utilisation of resources in the school system of Austria at the time of the visit of the OECD review team in June 2015. While generally following the common OECD guidelines when preparing the report, the authors put particular focus on the complex structures and mechanisms of school governance in Austria and notably the differentiation between the school system/types operated at the federal and provincial level, respectively, which is important in particular for primary and lower secondary education. Therefore the report puts special emphasis on these levels of the school system.

Three main challenges for Austrian schools are seen as requiring a response at all levels of the system: i) a discrepancy between achievement levels and high expenditure for the system, ii) inequity in outcomes with a high rate of social reproduction, and iii) the demographic development with respect to a total decrease in the number of children and a relative increase in the number of students with a migration background.

The Country Background Report is structured into six chapters.

Chapter 1 – National Context describes the main economic, social, demographic and political developments that shape education policy and governance in Austria. Even though Austria is characterised by a high degree of material wellbeing, a high quality of life and, in an international comparison, relatively high employment rates and low youth unemployment, it faces growing unemployment and decreasing growth rates, ranking near the bottom of the EU countries. Resource planning for Austrian education should take due account of several main factors, amongst them:

(1) Substantial demographic shifts with respect to the school-age population, which is stagnating after a period of substantial shrinkage and shows regionally very uneven trends today: Substantial growth is expected for Vienna while in many provinces (Laender) the numbers of pupils will stagnate or even decline.

(2) A high number of students with a migration background speak a language other than German at home.

In urban areas their share can exceed 50%.

(3) The specific shape of federalism in Austria which might be called ‘distributional federalism’ as it implies a fundamental split between the financing bodies and the spending bodies: About 90% of taxes and levies are collected by the federal level and then substantial shares are redistributed to the provincial level (‘Laender) and the municipalities. Negotiations about resource distribution between the federal and the provincial level are performed as a separate political activity outside of education policy and cover all the different policy fields jointly. Parameters for the funding of compulsory education are part of these negotiations, thus opening a field for political negotiations about schools outside of education policy.

Chapter 2 – School System describes the main features of the school system in terms of organisation, governance and performance. It aims to help readers understand the decision-making process, as well as the allocation and use of resources in the Austrian school system.

An important aspect of the education system is the strong diversification and selectivity of programmes at all levels. Students are subject to several selective transitions: a) the transition at age 10 from primary to lower secondary education with two different school types – AHS and NMS; b) different forms of ability tracking within school types; and c) the transition into a highly diversified system of upper secondary education. However, this cannot be generalised or simplified to a dichotomous choice between general or vocational education, since it includes the widely popular options for higher vocational education with their high social status and direct access to university education.

This chapter also highlights that, even though the public has the impression that reforms in the education system are often blocked, numerous projects of reform and redesign of the organisation and management of school have been initiated in the last decade and further reforms are envisaged. Major projects are the reform of lower secondary education (NMS), the reform of the teacher service codes and of teacher training, the introduction of educational standards and testing, the expansion of compulsory education by one year of free-of-charge pre-primary education, and the implementation of centralised final examinations providing access to universities. Further reforms are currently being discussed, such as a reform of school

- 7 administration with greater autonomy for individual schools.

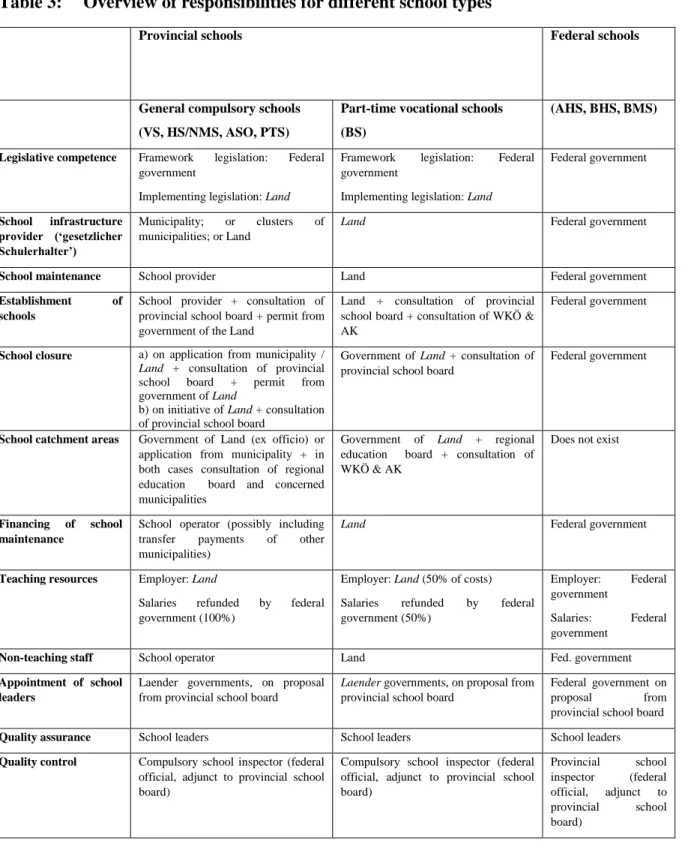

The governance of school education in Austria is characterised by a complex division of responsibilities between federal and provincial authorities. In a nutshell, the federal level is responsible for (framework) legislation, supervision of all schools and for the management and infrastructure of the so-called federal schools at secondary level (AHS, BHS), while the 9 provinces are responsible for the network of provincial schools (general compulsory schools, APS) at primary (VS) and lower secondary level (NMS) as well as special needs schools and schools in dual VET (Berufsschulen). This also includes the management of teaching resources (funded by the Federal Government), whereas infrastructure for provincial schools is generally provided by the municipalities. Two main institutional bodies share responsibilities in the implementation and management of school policy in each province: the provincial school boards, decentralised agencies of the Federal Government, which are responsible for school inspection and administration of federal schools, and the school departments of the provincial governments which are responsible for provincial schools. To secure regional influence on school administration, the provincial school boards – in principle federal authorities – include elements of provincial representation, which is mainly expressed by the fact that the school boards are chaired by the provincial governors and embrace consultative bodies which are composed of representatives from the respective province.

Chapter 3 – Governance of resource use in schools provides an overview on the level of resources and how they are governed within the school system. Expenditure per student in Austria is amongst the highest in the OECD. Total expenditure, in real terms, has risen by about one third since 1995 and 96% of the expenditure for primary or secondary institutions comes from public sources.

However, detailed reporting of unit costs by province and different classifications of school type is not standard in Austria due to the division of responsibilities between federal and provincial levels. Against this background, monitoring of resource use is challenging and the available information does not really allow for identifying how the discrepancy between relatively high expenditure and rather low achievement is related to the resource use at school level.

This chapter also discusses some policy issues which are related to the overall funding of school education and are subject to ongoing reform: Currently more than 77% of expenditure for schools in Austria is spent on personnel, mainly teachers. The salaries (service codes) for all teachers, no matter if they are employed by the federal or the provincial governments, are set by federal legislation. Any change in the salary scheme thus poses challenges or opportunities for the financing of education. In 2013 Austria adopted a major reform of the teacher service codes and of the remuneration of future teachers. It aims to reduce salary differences between teachers of different school types; salaries will generally start at a higher level, making the profession more attractive for new teachers, while flattening the slope of salary increases that come with years of service (rather than experience).

At the same time a new teacher training system is being implemented, aiming to develop a better trained future teaching force with master’s degrees as a general condition for permanent employment.

Chapter 4 – Resource distribution is concerned with how educational resources are distributed within the school system. In Austria a huge share of the educational budget is decentralised and managed at different levels of the education administration. The general principles for the transfer of funds from the federal to the provincial level for teaching resources for provincial schools (Landesschulen, APS) are set out in the Fiscal Adjustment Act (Finanzausgleichsgesetz). The Federal Government fully compensates the provinces for their expenditures on pedagogical staff based on a funding formula for staff plans. Parameters include enrolment – assuming certain pupil/teacher ratios for different types of school –, resources for a 3.2 pupil/teacher ratio for special needs education – assuming a fixed number of 2.7% enrolment in special needs education –, and additional funds are earmarked for policy priorities.

Resource distribution is distributed in a fragmented way between administrative political levels, with the distinction between provincial and federal schools, employing different categories of teachers partly for the same groups of students, and a distinct system of allocating the current expenditure and infrastructure.

There are no nationwide regulations for the distribution of these resources to schools by provincial governments. Criteria for the school network at provincial level are defined by implementing legislation of the Laender. Provincial schools (VS, NMS, ASO) are established and maintained by the municipalities – often supported by funds from the provincial government. Catchment areas aim to facilitate allocation of (teaching) resources to individual schools in line with enrolment numbers. Notably at primary level, Austria has a high number of small and very small schools, including due to the country’s topographical

- 8 features. Due to this division of competences, the Federal Ministry has no influence on the provincial school networks and the amount of resources that are deployed to an individual provincial school.

The resource allocation for federal schools is planned and implemented by the Federal Ministry and the provincial school boards: Teaching resources are allocated based on a funding formula including the number of pupils and class size and also earmarked value units for all-day schooling, pupils with special needs, etc. Only a very limited share of teaching resources is earmarked for specified schools. The redistribution to individual schools takes into account specificities of schools whereby differing procedures and criteria are applied by each of the nine provincial school boards.

Teachers and school leaders for provinces as well as for federal schools are recruited and assigned to specific schools by the responsible administrative body – school department of the provincial government or provincial school board. Depending on the type of school, teachers are either trained at university colleges of teacher education or at universities.

Chapter 5 – Resource utilisation is concerned with how resources are utilised, through specific policies and practices, for different priorities and programmes once they have reached the different levels of the school system. A key mechanism to match resources to individual students in Austria is selection and tracking of students in different school forms. Tracking within lower secondary schools is about to be abolished with the implementation of the new secondary school, which applies more individualised forms of learning and team teaching. An important means to channel resources to students is remedial teaching and additional instruction for students having a first language other than German.

This chapter also provides new data comparing student-teacher ratios and class sizes, providing insights into the variation of resource distribution between and within provinces and regions. Austria is known for having one of the most favourable student-teacher ratios in primary and lower secondary education amongst OECD countries, partially a consequence of a 2007 federal regulation which aimed to decrease the recommended number of pupils per class to 25 for pedagogical reasons. Classes in urban areas are typically much bigger than in rural areas and Laender with many rural schools tend to have more schools with small classes. Yet, when considering student-teacher ratios, the differences between urban and rural schools are much more moderate, suggesting that schools with bigger classes do not necessarily have considerably less ‘human resources’, but use them in a different way.

Another ongoing debate is about the provision of support staff for schools and the potential cost savings if administrative tasks are generally carried out by non-teaching staff. There are also calls for more school psychologists and social workers. A general difficulty in this context is the fact that non-teaching staff for provincial schools (administrative assistants, janitors, etc.) has to be provided and remunerated by the municipalities which run the schools.

Chapter 6 – Resource management is concerned with how resources are managed at all levels of the school system. It addresses issues concerning capacity building for resource management, monitoring of resource use, transparency and reporting, provided they have not already been introduced above. It also discusses the main challenge for resource management which is its distributed and fragmented nature based on the structure of the overall governance system that splits the different aspects of resource management into various processes at different levels of the system and takes responsibility for resource management away from schools as the location where the resources are being put into use. Consequently, there is no place where all the information from the different processes is compiled, which produces a lack of transparency about the resources spent in education.

- 9

ABBREVIATIONS

Schools and Programmes

AHS Allgemein bildende höhere Schule Academic secondary school

AHS-U AHS - Unterstufe AHS - lower level

AHS-O AHS - Oberstufe AHS - upper level

APS Allgemeinbildende Pflichtschulen

General compulsory schools (VS, HS, NMS, ASO, PTS)

ASO Sonderschule Special needs school

BHS Berufsbildende höhere Schule Colleges for higher vocational education BIST-Ü

M4, M8, E8

Überprüfung der Bildungsstandards in Mathematik 4, Mathematik 8, Englisch 8

Tests of educational standards

in mathematics 4, in mathematics 8, English 8 BMS Berufsbildende mittlere Schule Secondary technical and vocational school

BMHS BMS/BHS BMS/BHS

BS Berufsschule (Duale Ausbildung)

Part-time vocational school/apprenticeship (the dual system)

ECEC Frühkindliche Bildung Early childhood education and care

HS Hauptschule General secondary school

NMS Neue Mittelschule New secondary school

PTS Polytechnische Schule Pre-vocational school

VS Volksschule Primary school

VSS Vorschulstufe Pre-primary school within VS (‘Grade 0’)

PH Pädagogische Hochschulen University colleges of teacher education Selected federal laws – translation and online sources

BDG Beamten-Dienstrechtsgesetz Civil Service Code

https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?

Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=1 0008470&FassungVom=2014-01-01

BilDok Bildungsdokumentationsgesetz

https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?

Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=2 0001727

BFG Bundesfinanzgesetz Federal Finance Act

https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?

Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=2 0008870&FassungVom=2015-12-31 2015:

http://www.parlament.gv.at/PAKT/VHG/XXV /I/I_00051/imfname_348119.pdf

BLVG

Bundeslehrer-

Lehrverpflichtungsgesetz Federal Teachers Service Code

https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?

Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=1 0008205

B-SchAufsG Bundes-Schulaufsichtsgesetz

Federal Law on School Inspection

https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?

Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=1 0009264

B-VG Bundesverfassungsgesetz Federal Constitutional Law

https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?

Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=1 0000138

LDG Landeslehrer-Dienstrechtsgesetz

Federal Service Code for

https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?

Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=1

- 10

Provincial Teachers 0008549

LBVo

Leistungsbeurteilungs- verordnung

https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?

Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=1 0009375

FAG Finanzausgleichsgesetz Fiscal Adjustment Act

https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?

Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=2 0005610

GehG Gehaltsgesetz Federal Remuneration Act

https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?

Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=1 0008163

Pflichtschulerhaltungs- Grundsatzgesetz

Federal Act on the Maintenance of Compulsory Schools

https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?

Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=1 0009231True

PrivSchg Privatschulgesetz Private Schools Act

https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?

Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=1 0009266

SchOG Schulorganisationsgesetz Federal School Organisation Act

https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?

Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=1 0009265

SchPflG Schulpflichtgesetz Federal Compulsory School Law

https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?

Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=1 0009576

SchUG Schulunterrichtsgesetz Federal School Education Act

https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?

Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=1 0009600

SchZG Schulzeitgesetz Federal Law on Schooling Time

https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?

Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=1 0009575

Other abbreviations

AK Arbeiterkammer Österreich Austrian Chamber of Labour

ao Außerordentliche Schüler

Non-regular students due to difficulties with the language of instruction

BBG Bundesbeschaffung GmbH Federal Procurement Agency

BIFIE

Bundesinstitut für Bildungsforschung, Innovation & Entwicklung des österreichischen Schulwesens

Federal Institute for Educational Research, Innovation & Development of the Austrian School System

BMBF Bundesministerium für Bildung und Frauen

Federal Ministry of Education and Women's Affairs

BMWFW

Bundesministerium für Wissenschaft, Forschung und Wirtschaft

Federal Ministry for Science, Research and Economy (previously BMWF)

CPD Continuing Professional Development

CQAF Common Quality Assurance Framework

EAG Education at a Glance

ECTS European Credit Transfer System ESL Early school leavers

FTE Full-time equivalent GDP Gross domestic product

ILO International Labour Organization

ISCED International Standard Classification of Education

- 11

IV Industriellenvereinigung Federation of Austrian Industries

LSR Landesschulrat (‘Stadtschulrat’ für Wien) Provincial school board (‘Stadtschulrat’ for Vienna)

LK Landwirtschaftskammer Chamber of Agriculture

NBB Nationaler Bildungsbericht National Education Report Austria OECD

Organisation für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

PIRLS IEA: Progress in International Reading Literacy Study PISA OECD: Programme for International Student Assessment

PPP Purchasing power parity

QIBB QualitätsInitiative BerufsBildung VET Quality Initiative

SEN Special education needs

SPF sonderpädagogischer Förderbedarf Attested SEN SQA Schulqualität Allgemeinbildung

‘School Quality in General Education’

Initiative TALIS OECD: Teaching and Learning International Study

TIMSS IEA: Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study

UOE UNESCO/OECD/EUROSTAT Data Collection

VET Vocational education and training WHO World Health Organization

WIST Wirkungsorientierte Steuerung Performance Budgeting

WKÖ Wirtschaftskammer Österreich Austrian Economic Chamber

Naming of governmental levels

The translation of Austrian terminology for public authorities, administrative bodies, etc. and institutions of the school system generally follows the glossary of Eurydice and the chart of the school system by BMBF (see Figure 4).

The Government and all its entities at the central level are generally either called ‘federal’ or use the German term ‘Bundes-’.

The Government and all its entities at the level of the nine Laender (provinces) are generally either named

‘provincial’ or use the German term ‘Laender-’. One notable exception is the translation ‘provincial school board’ for ‘Landesschulrat’. On other occasions, the term ‘regional’ stands for sub-national units but is not tied to provinces.

The administrative level between provinces and municipalities is called ‘district’ or in German ‘Bezirk’.

The term ‘municipality’ is used for the local/communal administrations and governments (Gemeinden). It is used for rural municipalities as well as towns and cities. In the case of Vienna, which is one of the nine federal provinces of Austria, the ‘technical’ levels of the province (Land) and ‘municipality’ are not distinguished for the purposes of this report.

The term Landesschulen (provincial schools) in this report refers to the school types VS, HS, NMS, ASO, PTS and is not a legal term, but is often used for reasons of simplification when demonstrating the dichotomy of schools run by the federal administration (Bundesschulen) and those operated by the Laender.

- 12

Purpose and scope of this report

1. This report was prepared as an input to the OECD ‘Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools’. It is primarily of a descriptive nature and takes developments in school policy and reforms until June 2015 into account.

2. In this context the report has served two main purposes: Firstly, it aimed to help the preparation of the country review team, which was composed of OECD analysts and independent academic experts who visited Austria in June 2015, to enter into in-depth discussions and fact-finding with stakeholders of the Austrian education system, including visits to a limited number of Austrian schools in Vienna, Burgenland and Salzburg. The contextual information provided by this report, together with the information gathered by the review team during its country visit, served as the basis for the preparation of an OECD country review report on Austria, which will include also recommendations on how to improve the effectiveness of resource use in the Austrian school system.

3. Secondly, this Country Background Report provides a national input to the international debates, comparative analyses and synthesis reports, which are being developed under the broader framework of the OECD school resources project and are expected for publication as of 2016.

Scope of this report

4. This Country Background Report gives an overview on the distribution, utilisation and management of school resources in Austria. It has been elaborated on the basis of detailed guidelines provided by OECD, which aim to ensure a minimum level of comparability between different countries and their school systems.

5. While generally following these international guidelines in the preparation of the report, the authors have put an important focus on the structures and mechanisms of school governance in Austria and notably the differentiation between the school system/types operated by the federal level (Bundesschulen) and the system/school types administered by the nine provinces (Landesschulen). It has to be noted that this differentiation is primarily a feature of compulsory education (grades 1-9, i.e. primary and lower secondary education) in Austria.

6. To help the readers understand the administrative logic of the Austrian compulsory school system – which is mainly funded by the federal level, but dominated by largely separate mechanisms of resource distribution, diverging teacher employment conditions, distinct teacher training systems, an implicit hierarchy of schools, etc. – this report aims to give some insight into the complex, historically grown distribution of competences and responsibilities between the federation and its provinces. There is broad consensus among school experts, politicians and stakeholders that the pronounced fragmentation of competences is one major obstacle to more effective school resource use and resource monitoring in Austria.

7. Also, the formal and informal elements of checks and balances, which have developed over the years between the different layers of government (federal level, provinces, municipalities) and the stakeholders in the school system (teacher unions, political parties, parents’ associations, etc.), will be included in this report as they have enormous implications for the prevalent funding logic.

8. To give more room for the description and analysis of these challenging features of the Austrian school system, it has been decided to focus on the area of compulsory schooling in the report and also the country review.

9. This seems justified from the point of view that – with the exception of dual VET schools – the upper secondary school system is mainly funded and administered by only one jurisdiction, i.e.

the federal level, and is thus much less fragmented. Furthermore, upper secondary education and notably vocational education and training in Austria were extensively reviewed in the OECD

‘Learning for Jobs’ project in 2010 (OECD, 2010).

Main sources of information

10. This report builds on publicly accessible information, research reports and published data from the Eurostat UOE collection/OECD’s Education at a Glance, Statistics Austria and BIFIE. Only for

- 13 some detailed aspects of resource allocation, new indicators have been developed for the purpose of this report on the basis of data provided by BMBF.

11. In some merely descriptive sections of this report, information provided by the Eurydice

‘Description of national education systems’ was used or referred to.

12. For the ‘Main Challenges” sections, each of which concludes the analyses provided in chapters 2- 6, an ‘external’ academic assessment was provided by IHS, building upon extensive previous work of Lassnigg et al. on the structures and efficiency of the Austrian education system and its administration. (Lassnigg & Vogtenhuber, 2015; Lassnigg, Felderer, Paterson, Kuschej & Graf, 2007; for an extensive overview of the provincial structures in education see also Lassnigg, 2010).

13. This OECD review comes at a timely moment. Not only is the Austrian school system progressing progressing in the implementation or completing a number of reform steps in school education, including the introduction of a new secondary school, the common expectation is also that more structural reforms should be envisaged. High-level expert groups have been working on recommendations for such a reform since 2014 and the outcomes of the OECD review are expected to support this work.

- 14

Chapter 1: The national context

1.1 The economic and social context

14. Austria is characterised by a high degree of material wellbeing and a high quality of life. Steady growth in GDP per capita has been accompanied by low income inequality, high environmental standards and rising life expectancy (OECD, 2013b, p. 10). With 44,141 PPP$ in 2012, Austria has the sixth highest GDP per capita in the OECD group, well above the OECD average of 37,010 PPP$ and just behind Australia, United States, Switzerland, Norway and Luxembourg. High export and import rates show that Austria has a very open economy. In 2012, exports of goods and services represented 57.2% of GDP and imports 54.0% of GDP1 compared to an average (exports/imports) of 29.8%/29.8% in the OECD and about 45.8%/43.2% in the euro zone (OECD, 2014b). Small and medium-sized enterprises (less than 250 employees) play an important role in the Austrian economy. In 2010, 30.0% of employees worked in medium-sized and 11.9% in small enterprises, compared to 18.6% and 7.0% in the EU-27 group (Eurostat, 2013). Austria has a relatively strong agricultural and construction sector with 12.1% of employees compared to 9.0%

in the eurozone, while employment in services (59.6%) is slightly below the average of the eurozone (62.2%).

15. Austria’s employment rate is 72.3% (OECD, 2014b), well above the OECD average of 65.3% and an increase of 5% since 2000. The employment rate is especially high for 15- to 24-year-olds and above average for 25- to 55-year-olds, but below the OECD standards for the older cohorts.

However, for the cohorts aged 55 and above in particular, employment rates have risen since 2000, up from 28.3% to 44.9%.

16. Even though Austria’s unemployment rate, 4.9% in December 2014 (OECD, ILO definitions), is below those in most OECD member states and just half the EU-28 average, it is currently rising and above the rate before and during the crisis. From a national perspective, unemployment has reached the highest value since 2005 and has been on the rise since then. The unemployment rate according to the national definition reached 10.5% in January 2015, about one percentage point higher than in early 2014. One driver behind the growth in unemployment rates in 2014 is the growth in the workforce. In 2014 the number of unemployed grew by 36,000 while the number of employed grew as well, by 22,000. Overall, according to OECD, economic growth is still weak, largely because of low domestic demand; in more recent years, the favourable economic position of Austria has been slightly deteriorating, with growth ranking near the bottom of the EU, and also exports showing weaker performance than before. A turnaround in unemployment rates is not expected before late 2015 or 2016.

1.2 Demographic developments

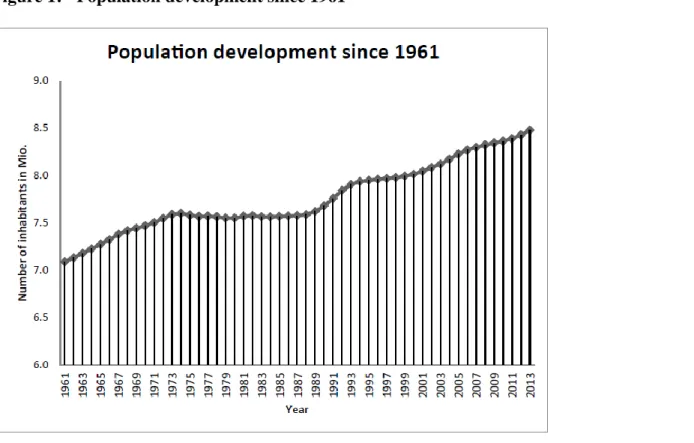

17. From 1961 to 2013, the population size in Austria increased by almost 1.4 million (+19.6%) from 7.09 to 8.48 million inhabitants. However, the increase was not steady; phases of strong growth alternated with periods of stagnation or slight decline. While in the 1960s, the population grew due to birth rate increases, the phase after the baby boom and negative migration balances caused a demographic decline in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Population growth since 1980 has mainly been driven by immigration and, less so, by rising life expectancy, which has increased by 11 years for men and 10 years for women since 1970.

18. Between 1988 and 1994, the high level of immigration as a result of the opening of Eastern Europe and slight birth increases led to strong growth rates, which were stopped in the mid-1990s due to more restrictive immigration policies. Since 2000, strongly increased immigration has

1 Exports and imports of goods and services consist of sales of goods and services (included/excluded in the production boundary of GDP) from residents to non-residents. Exports and/or imports and their sum can exceed the total GDP.

- 15 again led to rapid population growth (Statistics Austria, 2014a) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Population development since 1961

Source: Statistics Austria, 2014b.

19. The size of the employable population in Austria will remain rather stable in the next years. Today 61.8% of inhabitants are between 20 and 64 years old (5.24 million). By 2020, the size of the population in employment age will slightly increase to 5.41 million (+3%). Thereafter, the number of people reaching retirement age will be greater than the number of young people entering the labour market. By 2030, the size of the potential labour force will decrease to the current level (5.25 million) and the percentage of 20- to 64-year-olds will decrease from 61.8% (2013) to 57.1% (Statistics Austria, 2014b).

20. Austria’s population is projected to increase to more than 9 million inhabitants by 2025 as a result of immigration, an increase of 6.5% compared to 2013. By 2040, the population is expected to increase to 9,410,000 (+11.0% compared to 2013) (Statistics Austria, 2014b). Without immigration, the population would initially stagnate and then decrease to 8.12 million by 2040 (- 4%).

Migration

21. The proportion of foreign citizens in 2013 was 12.2% (1.03 million) (Statistics Austria, 2014a), of which 158,000 were German, 114,000 Turkish and 200,000 foreign citizens from Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (Statistics Austria, 2013, p. 20). Today, for education policy, citizenship is no longer a central perspective and the migration background of families has become the focus of attention. With respect to the school age cohorts, the distribution of children from migrant parents by origin is different from that of the total population because the migration pattern for younger cohorts of migrants is different from the earlier pattern. Nearly one in five grade 8 students in 2012 had a migration background (18.3%, including Germany), with more than two thirds of them born in Austria (2nd generation). The biggest group of migrants comes from the Western Balkans, i.e. former Yugoslavia (42%), Turkey (23%) and countries of the EU (16%, of which just 2.7% from Germany) (calculations based on BIST-Ü, M8, 2012).

22. Language is perceived as the most important aspect related to migration and education. Figure 2

- 16 shows the distribution of primary grade 4 students by language spoken at home (based on information provided by them). About one quarter of primary school students speak languages other than German at home, yet only 3% of the total indicate they do not speak German at all at home, 22% live in multilingual families. 84% of students with a migration background2 speak German, in a majority of cases in addition to another language (68%). One in six children of migrant families in Austria do not speak German. According to official school statistics, 53% of primary school children in Vienna speak another language (typically besides German) than German in everyday life, in major cities outside Vienna the rate is also high, between 35% and 47% (Bruneforth & Lassnigg, 2012, p. 37).

Figure 2: 4th grade students by language spoken at home

Source: Bruneforth & Lassnigg, 2012, p. 25.

23. There are also legally recognised minorities living in Austria who were granted special rights in the Austrian Independence Treaty of 1955. Austrian citizens belonging to the Slovene and Croat minorities have the right to establish organisations in their language which includes the right to instruction in primary education in the minority language and the entitlement to the provision of a proportionate number of secondary schools.

Demography and education

24. There are substantial demographic shifts with respect to the school age population. Today, 20% of the Austrian population are children aged below 20 years (1.69 million). Figure 3 shows the change in school age population between 1990 and 2030. For the age group of basic education (6 to 14), the population declined by about 10% in the last decade, but a change in the trend is projected for 2016 when the number of pupils of primary school age is expected to increase again for the following ten years. But this trend is regionally very uneven: Substantial growth is expected for Vienna while in many provinces the number of pupils will stagnate. The trends for upper secondary and tertiary student populations follow the trend of basic education with a shift of about 10 to 15 years.

2 In data from national assessments, migration is defined based on OECD definitions, but children from parents born in Germany are considered as non-migrants.

- 17 Figure 3: Change in school age population 1990-2030

Note: Only the Laender with the two most extreme trends are shown (Kärnten = Carinthia; Wien = Vienna).

Source: Bruneforth & Lassnigg, 2012, p. 19.

25. The development of educational levels from 1971 to 2012 shows a general increase in educational levels of the Austrian population. In 1971, the proportion of the population aged between 25 and 64 with compulsory education as their highest level of education was 57.8%, whereas in 2012 the proportion was 19.1%. Significant growth has been achieved in all higher secondary education programmes. The proportion of people whose highest qualification is from secondary technical and vocational school (BMS) (1971: 7.5%; 2012: 15.4%) or who have acquired a general qualification for university entrance (matriculation examination) (1971: 6%; 2012: 14.7%) more than doubled between 1971 and 2012. The increase is particularly evident in higher education:

while in 1971 only 2.8% of the Austrian population aged 25 to 64 years had a university degree, in 2012 the proportion was 12.5% (Statistics Austria, 2014c), which is still low by international comparison.

26. In recent decades, women in particular have caught up in terms of their level of education. In 1971, 70.4% of women and 43.4% of men between 25 and 64 years achieved only basic education, whereas in 2012, the proportions were 23.2% for women and 14.9% for men (Statistics Austria, 2014c). For the younger cohorts, women significantly outnumbered men with respect to completion of academic upper secondary education and tertiary education: 45% of women aged 25 to 29 completed ISCED 3A compared to just 40% of men; 17% of women completed ISCED 5A/6 compared to just 14% of men.

1.3 Political context

27. Austria is a federal state with a total area of 83,872 square kilometres (about 32,710 square miles), consisting of nine provinces or states (Laender). Austria is a parliamentary republic with a Federal Constitution established in 1920/1929 based on democratic, federal and legal principles, as well as on the principle of the separation of powers. The Federal President is the supreme representative of the state, elected directly by the people for a six-year term. The National Council and the Federal Council (Nationalrat and Bundesrat) are the legislative bodies of the Republic, with the latter being composed of representatives of the Laender, which guarantees their participation in federal legislation. The members of the National Council are elected every five years, the members of the Federal Council are appointed by the parliaments of the nine Laender. The Federal Government consists of the Federal Chancellor, the Vice-Chancellor and Federal Ministers.

- 18 Map: The federal states of Austria

Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f9/Austria_states_english.png (states = ‘Laender’)

The provincial parliaments (Landtage) are the legislative bodies of the Laender which are re- elected every five years, with the exception of Upper Austria with a six-year period. The provincial administration is headed by the provincial government (Landesregierung). In an international comparison, the number of Laender is quite high and untypical of such a small country. The size of Laender ranges from 287,000 inhabitants in Burgenland to 1.7 million in Vienna. Five of the Laender have less than one million inhabitants.

28. The municipalities enjoy a constitutionally guaranteed right to self-administration, being subject only to the legal supervision by the respective Land. They have an elected municipal council (Gemeinderat) headed by a mayor, who is elected either by the municipal council or, depending on the legislative provisions of the respective Land, by popular vote.

29. Austrian federalism has a specific shape which might be called ‘distributional federalism’, as most of the taxes (about 90%) are collected at the federal level and then redistributed to the Laender and the municipalities. Redistribution occurs partly according to specified responsibilities, or through the Fiscal Adjustment Act (Finanzausgleichsgesetz). The latter is negotiated every 4 years between the Federal Government, represented by the Ministry of Finance, the Laender represented by their governors (Landeshauptleute), and municipalities represented by the association of towns (Städtebund) and the association of municipalities (Gemeindebund). The result of these negotiations is adopted by the federal parliament. The Fiscal Adjustment Act currently concerns a sum of about € 80 bn. The agreements according to this redistribution constitute a kind of ‘automatic’ entitlement of the Laender and municipalities to receive a certain amount of the federal taxes, currently 21% for the Laender and 12% for municipalities.3 Because of the complex allocation of responsibilities among the different levels of education, these structures of Austrian federalism are a very important element of educational financing. Currently, attempts are being made to change the basic mechanisms of redistribution and, in addition, the

3 The Austrian federalism must not be confused with the Swiss one, as the Swiss cantons collect most of the taxes for their expenditure; and Austrian federalism is also not comparable with the German one in its organisational consequences because many German Laender are nearly as big as or bigger than Austria, which means that the federal responsibilities in Germany would be the equivalent to central federal responsibilities in Austria (in terms of distance to the schools or the local entities). These differences are often confused in the Austrian debate. If the distribution of responsibilities for schools is compared between governmental levels, the share of responsibilities of the provincial level is similar only to much bigger countries such as Germany, Spain, Italy (see Lassnigg, forthcoming 2015).

- 19 regulations about the financial governance of the Laender and municipalities are changing from a cameralistic accounting system to the standards of double accounting. According to these current structures it is difficult in several respects to get an accurate overview of the use of resources, which are federal by origin. As will be shown, this structure implies a fundamental split between the financing bodies and the spending bodies, in particular with the teachers in provincial schools.

An important point of current discussions is to shift a more substantial part of the collection of taxes from the federal level to the Laender level, which would bring more congruence between financing and spending responsibilities; however, there are also proposals to make this split even deeper by shifting more of the spending responsibilities to the Laender within the current federal taxing regime.

- 20 Figure 4: Amount of intergovernmental redistribution 2014

Tax revenue & expenditure by government levels (2014, % government levels only)

Tax revenue & expenditure by government levels (2014, million €, incl. social security)

41,260.31 52,163.62

10,802.04 25,292.01

5,327.13 2,676.18

106,631.62 67,805.59

Redistribution (million €) % of expenditure

Redistribution -38,826 21,349 14,490 % Expend. -57% 80% 57%

Source: Statistics Austria, Stat-CUBE, own calculations.

Fed Prov Com

% Expend. -57% 80% 57%

-80%

-60%

-40%

-20%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

% of expenditure

Fed Prov Com

Redistribution -38.826 21.349 14.490 -50.000

-40.000 -30.000 -20.000 -10.000 0 10.000 20.000 30.000

Redistribution (Mio EUR)

Tax revenue Expenditure

Communal (Gemeinden) 9% 21%

Provincial (Länder) 4% 22%

Federal (Bund) 87% 57%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Tax revenue & expenditure by government levels (2014, % government levels only)

Tax revenue Expenditure

Social Security 41.260,31 52.163,62

Communal (Gemeinden) 10.802,04 25.292,01

Provincial (Länder) 5.327,13 26.676,18

Federal (Bund) 106.631,62 67.805,59

0 20.000 40.000 60.000 80.000 100.000 120.000 140.000 160.000 180.000

Tax revenue & expenditure by government levels (2014, Mio. EURO, incl. social security)

Fed Prov Com

% Expend. -57% 80% 57%

-80%

-60%

-40%

-20%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

% of expenditure

Fed Prov Com

Redistribution -38.826 21.349 14.490 -50.000

-40.000 -30.000 -20.000 -10.000 0 10.000 20.000 30.000

Redistribution (Mio EUR)

Tax revenue Expenditure

Communal (Gemeinden) 9% 21%

Provincial (Länder) 4% 22%

Federal (Bund) 87% 57%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Tax revenue & expenditure by government levels (2014, % government levels only)

Tax revenue Expenditure

Social Security 41.260,31 52.163,62

Communal (Gemeinden) 10.802,04 25.292,01

Provincial (Länder) 5.327,13 26.676,18

Federal (Bund) 106.631,62 67.805,59

20.0000 40.000 60.000 80.000 100.000 120.000 140.000 160.000 180.000

Tax revenue & expenditure by government levels (2014, Mio. EURO, incl. social security)

Fed Prov Com

% Expend. -57% 80% 57%

-80%

-60%

-40%

-20%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

% of expenditure

Fed Prov Com

Redistribution -38.826 21.349 14.490 -50.000

-40.000 -30.000 -20.000 -10.000 0 10.000 20.000 30.000

Redistribution (Mio EUR)

Tax revenue Expenditure

Communal (Gemeinden) 9% 21%

Provincial (Länder) 4% 22%

Federal (Bund) 87% 57%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Tax revenue & expenditure by government levels (2014, % government levels only)

Tax revenue Expenditure

Social Security 41.260,31 52.163,62

Communal (Gemeinden) 10.802,04 25.292,01

Provincial (Länder) 5.327,13 26.676,18

Federal (Bund) 106.631,62 67.805,59

20.0000 40.000 60.000 80.000 100.000 120.000 140.000 160.000 180.000

Tax revenue & expenditure by government levels (2014, Mio. EURO, incl. social security)