Explaining the Outcomes of Negotiations of

Economic Partnership Agreements between the European Union and the African, Caribbean and Pacific Regional Economic Communities

-

Comparing EU-CARIFORUM and EU-ECOWAS EPAs

Inauguraldissertation zur

Erlangung des Doktorgrades der

Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der

Universität zu Köln 2016

vorgelegt von

M.A. James Nyomakwa-Obimpeh aus

Abease (Ghana)

ii

Referent: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Wessels, University of Cologne

Korreferent: Dr. Chad Damro, University of Edinburgh

Tag der Promotion: 19 October 2016

iii Acknowledgements

The generous support of a number of people and organisations have made the dream of completing a doctoral study a reality for me. I am first and foremost grateful to God for the grace and favour of life up to this point.

Particular thanks to my co-supervisors Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Wessels (University of Cologne) and Dr. Chad Damro (University of Edinburgh) for their insightful tutelage and patient guidance that has enabled me to achieve the goal of completing this study.

I would like to thank the European Commission whose funding through the EXACT Marie Curie ITN on EU external action provided me with much needed financial support, as well as the academic and professional networks within which I have completed this project. My deepest gratitude goes to “Benedikt und Helene- Schmittmann-Wahlen – Stiftung”, “Kölner Gymnasial- und Stiftungsfonds” and the

“Deutsche Akademische Austauschdienst” for granting additional financial supports.

Special thanks to the team of professionals in the wider EXACT Project network who provided vital advice and guidance to me: Prof. John Peterson (Edinburgh); Dr.

Edward Best and Dr. Sabina Lange at EIPA (Maastricht), Mirte van den Berge and Laura Ventura (TEPSA, Brussels); Professor Ramses Wessel, Dr. Elfriede Regelsberger, Dr. Anne Faber, Dr. Geoffrey Edwards, Prof. Brigid Laffan, Dr.

Robert Kissack, and Dr. Hanna Ojanen.

Very special thanks to EXACT project director Dr. Wulf Reiners and all the EXACT Fellows (Simon, Niklas, Leonhard, Vanessa, Andrew, Bogdana, Nicole, Marlene, Miguel, Marco, Andreas, Peter, and Anita and Tatjana) and the big team at the Jean Monnet Chair of Political Science and European Affairs (University of Cologne), for their great team spirit and inspiration in this academic and professional journey.

I also express my deepest appreciation to the officials and diplomats of European Union, ACP Secretariat, African Union Commission, ECOWAS Commission and CARIFORUM who readily helped me with all necessary data during the course of this research.

Mum Lydia Takyiwaa, as I promised, with the completion of this project, I have finally completed my long time of “schooling”. Thanks for your prayers and being there for me all the time. I am equally grateful to Mr. Jacob Boakye (Adom Super Blocks), Apostle Kingsford Kyei-Mensah, Apostle Jude Hama, Mr. Emmanuel Anane Boate, Mr. Frederick Asare, Mr Rick Taylor (York) and many other persons for their various roles in my personal quest for education and professional development.

To you, my lovely wife Berlinda thanks for all the support, sacrifices and

encouragement you offered, without which this project would not have been

accomplished.

iv Dedication

To my daughters Nhyiraba Takyiwaa and Anigye Boakyewaa, who give me

cause and inspiration every day to become their great father and teacher.

v Abstract

The European Commission has been negotiating Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) with Regional Economic Communities of African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States since 2002. The outcomes have been mixed. The negotiations with the Caribbean Forum (CARIFORUM) concluded rather more quickly than was initially envisaged, whereas negotiations with West African Economic Community (ECOWAS) and the remaining ACP regions have been dragging on for several years.

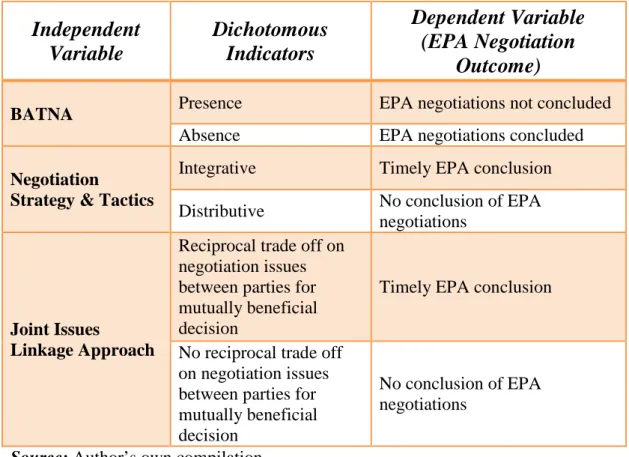

This research consequently addresses the key question of what accounts for the variations in the EPA negotiation outcomes, making use of a comparative research approach. It evaluates the explanatory power of three research variables in accounting for the variation in the EPA negotiations outcomes – namely, Best Alternative to the Negotiated Agreement (BATNA); negotiation strategies; and the issues linkage approach – which are deduced from negotiation theory.

Principally, the study finds that, the outcomes of the EPA negotiations

predominantly depended on the presence or otherwise of a “Best Alternative” to the

proposed EPA; that is then complemented by the negotiation strategies pursued by

the parties, and the joint application of issues linkage mechanism which facilitated a

sense of mutual benefit from the agreements.

vi Table of Contents

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS III

DEDICATION IV

ABSTRACT V

TABLE OF CONTENTS VI

LIST OF TABLES, FIGURES, AND BOXES X

List of Tables x

List of Figures xi

List of Boxes xi

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS XII

PART I: INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY 14

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 15

1.1. Research Interest: Twofold 21

Is there a limit to EU’s negotiation power and leverage? 22

How does Negotiation Theory help to Explain EPA (International Trade) Negotiation Outcomes? 23

1.2. Research Questions 24

1.3. Research Design and Variables 25

Comparative Case Study 25

Dependent Variable 27

Independent Variables 27

1.4. Relevance and Implications of Study 29

1.5. Thesis Structure 30

PART II: LITERATURE REVIEW ON THE EU AND THE ACP GROUP OF

STATES 32

vii

CHAPTER 2: EUROPEAN UNION’S TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT RELATIONS WITH ACP COUNTRIES; THEORY AND PRACTICE 33

2.1. Discourse on the European Union as a Global (Trade) Actor 33 2.2. EU Relations with Africa, Caribbean and Pacific countries in practice 38

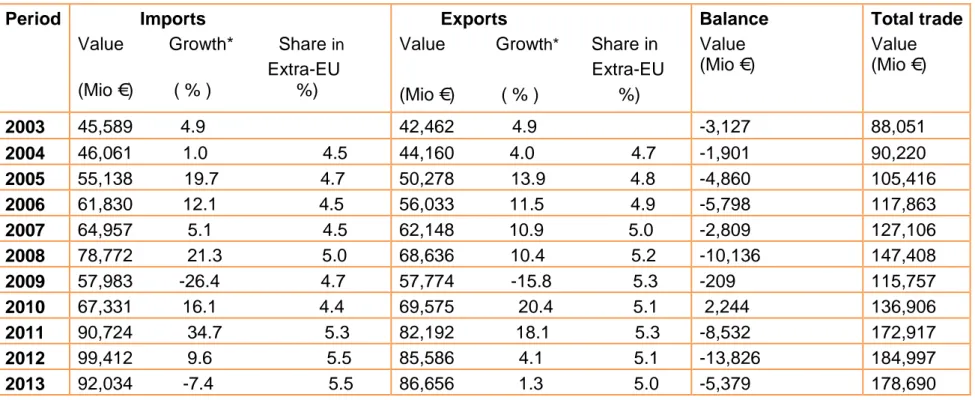

The ACP Group’s Global Trade Position 39

ACP Group’s Trade Dependence on EU 40

ACP Group’s Development Aid Dependence on the EU 44

Evaluation of EU Trade Preferences for ACP Group 45

EU-ACP Trade in relation to the WTO Regime 46

The Future of EU-ACP Relations 47

2.3. A Dawn of a New Era in EU Trade Policy with ACP: Negotiating EPAs 48

EPA Impact Studies 49

Thematic Studies on Proposed EPAs 52

Conclusion 55

PART III: THEORETICAL AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 56 CHAPTER 3: CONCEPTUALISING EU-ACP INTERNATIONAL TRADE

NEGOTIATIONS 57

3.1. Negotiation Analysis adapted as a Conceptual Framework 58

Best Alternative to the Negotiated Agreement 60

Bargaining Strategies and Tactics 63

Issue linkage 67

3.2. Analytical Model Structures of Negotiation Analysis 71

3.3. Conclusion 74

CHAPTER 4: METHODOLOGY AND RESEARCH DESIGN 79

4.1. Qualitative (not Quantitative) Study 79

4.2. Most-Similar Systems Comparative Case Study Design 81

4.3. Data Collection Techniques 87

Primary Data Collection Methods 87

Secondary Data Collection Methods 90

4.4. Data Analysis Approach - Establishing a causal link between Research Variables 91

Comparative Analysis 91

Content & Document Analyses 93

Process Tracing Technique 96

viii

4.5. Research and Methodological Reliability 100

4.6. Conclusion 102

PART IV: STATING THE EMPIRICAL CASES 103

CHAPTER 5: EMPIRICAL CASE STUDY I: INTRODUCING CARIBBEAN FORUM

AS REGIONAL ECONOMIC COMMUNITY 105

5.1. Introducing Caribbean Forum 105

5.2. Political and Institutional Contexts of Caribbean Region 107

5.3. Social and Economic Development Contexts 110

CARIFORUM-EU Trade in Goods 112

CARIFORUM-EU Trade in Services 114

5.4. State of Regional Integration in CARIFORUM 116

5.5. Describing EU-CARIFORUM EPA Negotiations 120

Negotiation Processes and Structures 120

Topics Covered in the EU-CARIFORUM EPA Negotiations 126

State of Play of EU-CARIFORUM EPA Negotiations 127

5.6. Conclusion 130

CHAPTER 6: EMPIRICAL CASE STUDY II: INTRODUCING ECONOMIC COMMUNITY OF WEST AFRICAN STATES AS REGIONAL ECONOMIC

COMMUNITY 131

6.1. Introducing the Economic Community of West African States 131

6.2. Political and Institutional Contexts 134

6.3. Social and Economic Development Contexts 137

ECOWAS-EU Trade in Goods Indicators 142

ECOWAS-EU Trade in Services Indicators 143

6.4. State of Regional Integration in ECOWAS 145

6.5. Describing EU-ECOWAS EPA Negotiations 150

Negotiation Structures and Processes 150

Topics and Issues covered in EU-ECOWAS EPA Negotiations 159

State of Play of EU-ECOWAS EPA Negotiations 161

6.6. Conclusion 162

ix

PART V: COMPARING THE REGIONAL EPA NEGOTIATIONS & MAJOR

CONCLUSIONS 164

CHAPTER 7: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE EPA NEGOTIATION

OUTCOMES 165

7.1. Assessment of the Role of Best Alternative to Negotiated Agreement (BATNA) to EPA

Negotiation Outcome 167

Impact of perceived or actual alternative to the ACP-EU EPA negotiations in general 168

In search for a Best Alternative to EU-CARIFORUM EPA 170

In search for a Best Alternative to EU-ECOWAS EPA 177

Conclusion 184

7.2. Appraising the Impact of Strategies & Tactics on the Outcome of EPA Negotiations 187

The ZOPA of EU 188

The ZOPA of ACP Group 189

EPA Negotiation Strategies followed by the EU and the ACP Group 192

Negotiation Tactics Used By Parties in EPA Negotiations 194

I. Negotiation Tactics of EU 194

II. Negotiation Tactics of the ACP Group 203

Impact of Dominant Negotiation Strategies on EU-all-ACP level EPA negotiation Outcomes 208

CARIFORUM-EU EPA Negotiation Strategies & Tactics 209

ECOWAS-EU EPA Negotiation Strategies & Tactics 214

Conclusions and implications of the Negotiating Strategies & Tactics 233

7.3. Issues linkage and the outcomes of the EPA negotiations 240How EPA Negotiations were linked with other Issues by the EU and ACP Group 240

EU-CARIFORUM EPA Negotiation and Linkage of Development Aid 252

EU-ECOWAS EPA Negotiations and Linkage of Development Aid 255

Conclusion 258

7.4. Conclusion: Explaining Different Outcomes of EPA Negotiations between CARIFURUM &

ECOWAS 259

CHAPTER 8: CONCLUSION AND FUTURE OUTLOOK 261

8.1. Key Research Findings 262

Implications of the Usefulness of Negotiation Analytic Approach (Negotiation Theory) on

Conventional IR/EU theories 265

The EU and EPA Policy: Negotiation Processes and Outcomes 268

The Odd Success: Why EU-CARIFORUM EPA was First to Conclude 270

Explaining the Prolonged EPA Negotiations between the EU and the ECOWAS 271

8.2. Future Research Outlook and Policy Recommendations 272

Future Research Recommendations 272

Policy Recommendations 274

x

REFERENCES 277

APPENDIXES 315

Appendix 1: Guiding Interview Questionnaire 315

Appendix 2: List of Interviews 318

Appendix 3: UN Classified List of Least Developed Countries 320 Appendix 4: Indicative List of Official Documents utilised in this Thesis 321 Appendix 5: Profile of CARIFORUM Region's Trade with World, 2003-2013 328 Appendix 6: Profile of ECOWAS Trade in the World (2003-2013) 329 Appendix 7: List of peer reviewed PhD-related research presentations and workshops attended by

the Author 330

List of Tables, Figures, and Boxes

List of Tables

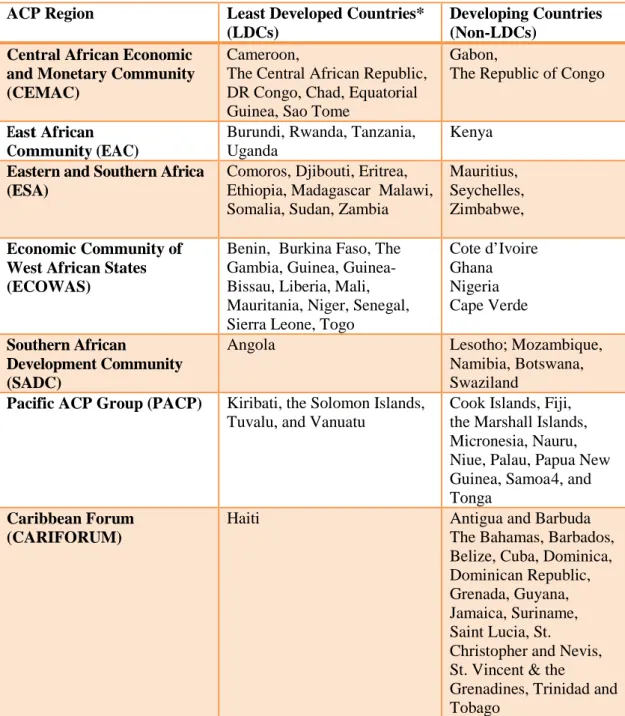

TABLE 1: LIST OF ACP REGIONS AND COUNTRIES AND THEIR DEVELOPMENT STATUSES ... 17

TABLE 2: EU-27 TRADE WITH MAIN PARTNERS (2012) ... 41

TABLE 3: THE EUROPEAN UNION, TRADE IN GOODS WITH ACP (AFRICAN, CARIBBEAN AND PACIFIC COUNTRIES) – 2003-2013 ... 43

TABLE 4: EU REGIONAL LEVEL FUNDING ALLOCATIONS TO CARIFORUM AND ECOWAS ... 83

TABLE 5: SUMMARY OF SIMILARITIES BETWEEN CARIFORUM AND ECOWAS RECS ... 86

TABLE 6: INDICATION OF ELITE INTERVIEWS CONDUCTED BASED ON PURPOSIVE SAMPLING ... 89

TABLE 7: MEASUREMENTS AND OPERATIONALISATIONS OF RESEARCH VARIABLES ... 99

TABLE 8: SELECTED PROFILES OF THE CARIFORUM REGION ... 106

TABLE 9: ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PROFILE OF CARIFORUM COUNTRIES... 111

TABLE 10: TOP 10 CARIFORUM TRADING PARTNERS IN GOODS -2013 ... 112

TABLE 11: CARIFORUM-EU EPA RATIFICATION (AS AT AUGUST 2014) ... 129

TABLE 12: SELECTED PROFILES OF ECOWAS COUNTRIES + MAURITANIA ... 133

TABLE 13: ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS OF ECOWAS COUNTRIES + MAURITANIA, 2004 ... 138

TABLE 14: ECOWAS’ REAL GDP GROWTH RATE IN PERCENTAGES 2008-2012 ... 140

TABLE 15: ECOWAS SHARE OF GLOBAL TRADE (EXPORT & IMPORT) FROM 1970-2010 IN COMPARISON WITH OTHER REGIONS IN THE WORLD ... 141

TABLE 16: EU-27/28 TRADE IN SERVICES WITH ECOWAS COUNTRIES (EUR MILLION) 2007-2009 .... 144

TABLE 17: ALTERNATIVE TRADE REGIMES AVAILABLE TO THE CARIFORUM MEMBER STATES IN THE ABSENCE OF EPA ... 172

TABLE 18: ALTERNATIVE TRADE REGIMES AVAILABLE TO THE ECOWAS MEMBER STATES IN THE ABSENCE OF EPA ... 178

TABLE 19: TRADE CREATION AND DIVERSION EffECTS OF EPAS FOR ECOWAS COUNTRIES (US$) .... 180

TABLE 20: LOSS OF REVENUE IMPLICATIONS OF AN EU-ECOWAS EPA (MILLION US$) ... 182

xi

TABLE 21: COMPARING VARIATION OF TARIFF REVENUE LOSSES (%) UNDER EPA AND GSP SCHEMES

... 215

List of Figures FIGURE 1: EU SHARE* OF GLOBAL TRADE IN GOODS & SERVICES FROM 2004-2013 IN COMPARISON WITH OTHER MAJOR WORLD ECONOMIES (%) ... 40

FIGURE 2: EU TOTAL TRADE IN GOODS WITH CARIFORUM 2005 - 2014 ... 113

FIGURE 3: EU-CARIFORUM TRADE IN SERVICE STATISTICS 2010-2012, IN BILLION EUROS ... 114

FIGURE 4: REGIONAL INTEGRATION CONFIGURATIONS IN THE CARIFORUM REGION ... 118

FIGURE 5: STRUCTURES OF THE EU-CARIFORUM EPA NEGOTIATIONS... 124

FIGURE 6: MAP OF ECOWAS ... 132

FIGURE 7: EU TRADE IN GOODS WITH ECOWAS, ANNUAL DATA 2004 - 2013 ... 143

FIGURE 8: REGIONAL INTEGRATION CONFIGURATIONS IN WEST AFRICA ... 148

FIGURE 9: EU-ECOWAS EPA NEGOTIATION STRUCTURE... 152

FIGURE 10: CARIFORUM SHARE IN TOTAL EU IMPORTS (1999-2004) IN COMPARISON WITH OTHER ACP EPA NEGOTIATING REGIONS ... 175

FIGURE 11: EU EXPORTS AND IMPORTS TO/FROM ACP GROUP (IN EUR MILLION) ... 191

FIGURE 12: EPA NEGOTIATING CONFIGURATIONS IN AFRICA ... 197

List of Boxes BOX 1: INDICATIVE PROVISIONS OF PROPOSED EPA BETWEEN THE EU AND ACP REGIONAL ECONOMIC COMMUNITIES ... 18

BOX 2: INDICATIVE TIMELINE OF EU-ALL-ACP EPA NEGOTIATIONS ... 19

BOX 3: BILATERAL TRADE BETWEEN EU AND ECOWAS, 2005 ... 26

BOX 4: INDICATIVE TIMELINE OF EU-CARIFORUM EPA NEGOTIATIONS ... 122

BOX 5: ISSUES COVERED IN THE EU-CARIFORUM EPA NEGOTIATIONS ... 126

BOX 6: INDICATIVE TIMELINE OF EU-ECOWAS EPA NEGOTIATIONS ... 155

BOX 7: ISSUES COVERED IN THE EU-ECOWAS EPA NEGOTIATIONS ... 160

xii List of Abbreviations

ACP Africa, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States ACP-EU JPA ACP-EU Joint Parliamentary Assembly

ADEID Action pour un Développement Équitable, Intégré et Durable (Cameroon)

AfDB African Development Bank

ASEAN Association of South East Asian Nations

AU African Union

AUC African Union Commission

BATNA Best Alternative to the Negotiated Agreement CACID Centre africain pour le commerce, l’intégration et le

développement

CAP Common Agricultural Policy CARICOM Caribbean Common Market CARIFORUM Caribbean Forum

CECIDE Centre du Commerce International pour le Developpement (Guinea)

CEMAC Economic and Monetary Community of the Central African Countries

CIECA Centro de Investigación Económica para el Caribe - Dominican Republic

CNPANE-AC Le Comité National de Pilotage des Acteurs Non Etatiques du Mali

COMESA Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa

CRITI Caribbean Regional Information and Translation Institute CTA Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation ACP-

EU

CSPs Country Strategy Papers EBA Everything But Arms

EC European Commission

ECDPM European Centre for Development Policy Management ECOWAS Economic Community of West African States

EEC European Economic Community

EPA Economic Partnership Agreement ESA Eastern and Southern Africa

EU28 European Union member states (currently 28)

EU-ACP European Union- Africa, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States

EU European Union

EUROSTEP European Solidarity Towards Equal Participation of People FSS Forum Social Sénégalais (Senegal)

FTA Free Trade Areas/Agreements FTAA Free Trade Area of the Americas

GARED Le Groupe d’Action et de Réflexion sur l’Environnement et le Développement (Togo)

GATT General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade GAWU General Agricultural Workers Union (Ghana) GNP Gross National Product

GRAPAD Groupe de Recherche et d’Action pour le Promotion de

l’Agriculture et du Développement (Benin)

xiii

GSP Generalized System of Preferences GSP+ Generalized System of Preferences-Plus GTLC Ghana Trade and Livelihoods Coalition

ICTSD International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development LDCs Least Developed Countries

MAR Market Access Regulation

MERCOSUR MERcado COmún del SUR (Customs Union of five Southern- cone countries Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela).

MFN Most Favoured Nation (clause)

MNSC Mouvement National pour la Société Civile (Guinea Bissau) MTRs Mid-Term Reviews

NAA Negotiation Analytic Approach

NANTS National Association of Nigerian Traders OAS Organization of American States

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development OECS Organization of Eastern Caribbean States

OSCAF-CI Organisation de la Société civile de l’Afrique Francophone - Côte d’Ivoire

PASCAO de la Plateforme des organisations de la société civile de

l’Afrique de l’Ouest sur l’Accord de Cotonou (West Africa Civil Society Platform)

PASCIB Plateforme des Acteurs de la Société Civile du Benin REC Regional Economic Communities

REPA Regional Economic Partnership Agreements

RODDADH Réseau Nigérien des ONG de Développement et Associations des Droits de l'Homme et de la Démocratie (Network of 70

Development NGOs -Niger)

RPTF Regional Preparatory Task Forces

RTA Regional Trade Agreement

SADC Southern African Development Community SIA Sustainability Impact Assessment

SPONG Le Secrétariat Permanent des Organisations Non Gouvernementales (Burkina Faso)

SPS Sanitary and Phytosanitary (Agreement)

SSA Sub-Saharan Africa

TANGO The Association of Non-Governmental Organizations in the Gambia

TCDA Trade, Development and Cooperation Agreement (EU-South Africa Trade Agreement)

TUC Trade Union Congress (Ghana) TWN Third World Network-Africa

UEMOA West African Economic and Monetary Union

UNCTAD United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

UN United Nations

WAEMU West African Economic and Monetary Union WTO World Trade Organisation

PACP Pacific ACP Region

14

Part I: Introduction and Background of the Study

15 Chapter 1: Introduction

The European Union (EU) has a long history of trading with the Africa, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries with the purpose of fostering their smooth and gradual integration into the world economy. It is hoped that that would subsequently facilitate their sustainable development and thereby reduce or eradicate poverty. In line with this aim, in the year 2000, in what is known as the “Cotonou Partnership Agreement” (CPA) reached between EU and ACP states, a time frame was set for the EU to begin negotiations with the ACP Group for regional Economic Partnership Agreements (see ACP Group of States and European Community and its Member States 2000). These negotiations were also partly prompted by the need to comply with a non-discriminatory rule of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). The two partners had until the end of December 2007 to remove preferential treatment that the EU gave to the ACP States in an effort to bring their trading relationship in compliance with rules of the global trade governing body (see WTO Ministerial Conference 2001).

Negotiations, therefore, started in 2002 for new Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) with the aim of concluding them by the end of 2007 and their coming into force effective January 1, 2008. The outcomes of the EPA negotiations, however, in 2007 fell short of that expectation; and to date negotiations are ongoing due to strong disagreements between the EU and the stakeholders of the ACP Group over several aspects of the proposed EPAs, regarding their possible negative impact on the development aspirations of the ACP Group.

The EPAs, according to the Cotonou Agreement which serves as the legal

basis for their negotiations, are to create full bi-regional Free Trade Agreements

(FTAs) between the EU on the one hand, and individual Regional Economic

Communities (RECs) of the ACP Group on the other. They are supposed to change

entirely trade relations and the structure between the partners – as they replace

existing unilateral preferential access to the EU market with reciprocal market access

between both partners. This means the ACP countries are to reciprocate their trade

relationships with the EU by equally liberalising tariffs on EU goods and services

entering their markets.

16

The EPAs are also to cover trade in services as well as additional binding rules in new policy areas such as investments, competition, and government procurements among others as discussed below. It is these original proposals made by the EU in the EPAs that generated huge debate among policy makers and academics in ACP countries as well as in the EU about the feasibility of it being a tool for development. While some (mainly EU) actors support the EPAs as proposed with several favourable arguments, others including politicians, civil society organisations, bureaucrats, and academics in both regions have vehemently opposed them, advancing several reasons for their positions.

As of now (May 2016), the state of negotiations is that out of the six/seven

1Regional Economic Communities (RECs) in the ACP regions, only the Caribbean Forum (CARIFORUM) has signed and implementing a full (trade in goods and services) regional level EPA with the EU with an advanced ratification process.

2Negotiations with the remaining six ACP RECs have not concluded. In cases where regional level EPA negotiations have not concluded, some individual ACP countries have signed or initialled interim bilateral agreements with the EU while awaiting the conclusion of the regional level negotiations. Some other countries have refused to sign any form of EPA with the EU.

3For an overview of ACP regions and their respective countries with an indication of levels of development, see Table 1 below;

1

Initially there were six RECs negotiating the EPAs with the EU but the East-Africa Community was devolved from the existing Eastern and Southern Africa and Southern-African Development Community framework for a separate negotiation.

2

According to the initial plan, all seven trading blocs in the ACP region were to sign and begin to implement the EPAs with effect from 1 January 2008.

3

See most recent EPA update issued by the European Commission. 2016

17

Table 1: List of ACP Regions and Countries and their Development Statuses ACP Region Least Developed Countries*

(LDCs)

Developing Countries (Non-LDCs)

Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC)

Cameroon,

The Central African Republic, DR Congo, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, Sao Tome

Gabon,

The Republic of Congo

East African Community (EAC)

Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda

Kenya Eastern and Southern Africa

(ESA)

Comoros, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Madagascar Malawi, Somalia, Sudan, Zambia

Mauritius, Seychelles, Zimbabwe,

Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)

Benin, Burkina Faso, The Gambia, Guinea, Guinea- Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Togo

Cote d’Ivoire Ghana Nigeria Cape Verde Southern African

Development Community (SADC)

Angola Lesotho; Mozambique,

Namibia, Botswana, Swaziland

Pacific ACP Group (PACP) Kiribati, the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu

Cook Islands, Fiji, the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Nauru, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa4, and Tonga

Caribbean Forum (CARIFORUM)

Haiti Antigua and Barbuda

The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, Saint Lucia, St.

Christopher and Nevis, St. Vincent & the

Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago

Source: Author’s own compilation based on UN Country Classification and EU’s EPA negotiation regional groupings. *What are LDCs? using the following three criteria; Gross National Income (GNI) per capita, Human Asset Index (HAI) and Economic Vulnerability Index (EVI), the UN defines Least Developed Countries (LDCs) as “low- income countries suffering from structural impediments to sustainable development.” (see United Nations 2013). The UN approved list of Least Developed Countries is found in Appendix 3.

4

Samoa moved from LDC to become a developing country in 2014.

18

Elements of the Proposed Economic Partnership Agreements

On the basis of EU proposal for the EPAs (derived from the so-called “Council Mandate”) and on the basis of the interim EPAs initialled or signed between the EU and some ACP countries and regions as well as on the basis of the only “full regional EPA” signed between the EU and the CARIFORUM, the elements of the EPAs include provisions such as listed in Box 1 below;

Source: Author’s compilation based on original official documents on EPA (ACP Group of States 2002; European Commission 2002a, b, 2004b, c).

As can be seen, the proposed EPAs are; to establish FTAs between the EU and the ACP regions; to liberalise trade in goods and services between the parties; improve on Rules of Origin; cover rules on investments; competition policy among others as highlighted above.

While the EU has insisted on all of these provisions (as provided in Box 1 above) in the EPA, the ACP Group in general and the Regional Economic Communities (RECs) have opposed the inclusion of some of them – especially the inclusion of the so-called “Singaporean issues”, which include public procurement,

Among the originally proposed issues to be covered under the EPA negotiation included:

a. The establishment of regional Free Trade Areas (FTA) between the EU and ACP regions.

b. Liberalisation of trade in goods and period of transition towards full liberalisation in ACP countries ranging from 10-12 and maximum of 15 years.

c. Rules of Origin (RoO) on traded goods.

d. Provisions on trade facilitation.

e. Provisions on Technical Barriers of Trade (TBT).

f. Liberalisation of trade in services.

g. Binding rules on investments.

h. Provision on competition policy.

i. Binding rules on government/public procurements.

j. Binding rules on innovation and protection of Intellectual Property Rights (IPR).

k. Provision on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS).

l. Provisions on development cooperation.

m. Provisions on agricultural and fisheries

n. Inclusion of Most Favoured Nation (MFN) and National Treatment (NT) clauses and

Box 1: Indicative Provisions of Proposed EPA between the EU and ACP Regional

Economic Communities

19

rules on investment, and competition policy as well as trade facilitation – mainly because those are not even yet agreed upon at the WTO level (see ACP-EC Council of Ministers 2008; ACP-EU Council of Ministers 2008a, b; ACP Council of Ministers 2004, 2005a, 2007a, b, 2014; ACP Heads of State and Government 2008, 2012).

Additionally, although the ACP RECs have been demanding additional financial resource commitment from the EU to support their transition to full liberalisation and market access under the proposed EPA regime, the EU has refrained from committing to giving such legally binding additional financial resource (see ibid.). The EPA negotiations, therefore, are still ongoing with divergence views between the EU and the ACP regions. Below in Box 2, an indication of an overview of the evolutionary timelines regarding the EPA negotiation policy of the EU is offered.

Box 2: Indicative Timeline of EU-all-ACP EPA Negotiations

• 9 April 2002: European Commission proposes Recommendation for Council Decision for the negotiations of Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) with ACP countries and regions (SEC (2002) 351 final).

• 17 June 2002: EU foreign ministers unanimously adopted a mandate for the European Commission to negotiate EPAs with the ACP

• 21 June 2002: ACP Trade and Finance Ministers agree on EPA negotiation guidelines for the ACP regions.

• 27 June 2002: ACP Council confirms guidelines for ACP regions to negotiate EPA with EU.

• 5 July 2002: ACP publishes the adopted Guidelines for EPA negotiation (ACP/61/056/02 [FINAL]).

• 27 September 2002, Brussels: the European Union and all-ACP countries officially opened negotiations for Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs)

• 30 October 2002, ACP House, Brussels: 1st all-ACP – EU Ambassadorial level meeting on negotiations of Economic Partnership Agreements. Issues discussed included; Structure for the negotiations; Issues to be considered during Phase I;

Procedure for moving from Phase I to Phase II; establishment of a Joint ACP-EU Steering Committee on WTO negotiations and calendar of meetings:

• 9 December 2002, ACP House, Brussels: 2nd all-ACP- EU Ambassadorial Meeting on EPA. Issues discussed were objectives, principles and overall structure of EPAs and legal statuses of EPA

• 5 & 7 February 2003: 1st meeting of the Specialized Group on legal issues.

Issues negotiated on included; Principles and objectives of the EPAs; General

structure and content of the EPAs; Definition of Parties to the EPAs; Conclusion

of the All-ACP phase; The non-execution clause; Dispute settlement;

20

Compatibility of the EPAs with WTO rules and Procedures for the entry into force of the EPAs

• 12 February 2003, Borschette Centre, Brussels: 3

rdACP-EC Ambassadorial on EPA

• 17 February 2003: 2nd session of the Specialized Group on legal and

• other issues of the EPA negotiations

• Friday, 21 February 2003, ACP House-Brussels: First dedicated session on the development dimension of EPAs. The discussion focused on EPAs as an instrument for development; and the link between EPAs and development co- operation.

• 11 April 2003: Second Dedicated Session on the Development Dimension of EPAs

• 15 April 2003, Brussels: First dedicated session on market access

• 6 May 2003: Fifth ACP-EC Ambassadorial meeting on EPA. Discussion focussed on legal issues on EPAs, development dimension of EPAs, and report on market access.

• 4 June 2003, ACP House, Brussels: Third dedicated session on the development dimension of EPAs

• 13 June 2003: 3

rdSession of Specialized Group on legal issues in Brussels. Issues discussed were on preserving the acquis of Lome/Cotonou Agreements,

Commodity Protocols, EPA compliance with WTO rules, and the legal status of all-ACP-EU Level EPA agreement.

• 25 June 2003, ACP House, Brussels: a dedicated session on the development dimension of EPAs in the area of services. Focus of discussion was on the development of the services sector in the ACP regions

• 27 June 2003, ACP House, Brussels: Fourth dedicated session on the development dimensions of the EPAs, Discussion focussed on industrial development and regional integration.

• Tuesday, 1 July 2003, ACP House-Brussels: First dedicated session on trade- related with negotiations focusing on the exchange of views on trade-related issues.

• 3 July 2003 at 10:00 a.m. at ACP House, Brussels: Second Dedicated, Session on Market Access

• 4 July 2003: 6th ACP-EC Ambassadorial negotiations on EPA

• Friday, 11 July 2003, ACP House, Brussels: Seventh ACP-EC Ambassadorial Meeting on the negotiation of EPAs. On the agenda was Agriculture and Fisheries; trade in Services; Trade Related Issues and transition from all-ACP phase of negotiations to the second phase

• 26 September 2003, Brussels: adoption of ACP Follow-Up Mechanism For Phase II of the EPA Negotiations

• 2 October 2003, Brussels: Joint Report on the all-ACP – EC phase of EPA negotiations

• 2 October 2003: ACP Council of Ministers and European Union (EU) Commissioners for Trade and Development launch the second ACP-EU Ministerial Meeting for the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) negotiations.

• 20 December 2007: Council of the EU adopted the Regulation (EC) No

21

1528/2007, which set the EU import regime for the African, Caribbean, and Pacific countries that had negotiated, but not yet signed and ratified, Economic Partnership Agreements

• 22 October 2012: initial EU Council position on proposed amendment of Market Access Regulation (MAR) 1528/2007.

• 30 November 2012: a draft EU Council statement was issued on the EC proposal to amend Market Access Regulation (MAR) 1528/2007.

• 11 December 2012: the European Council confirmed its position, supporting the Commission’s deadline of 1 January 2014 for the conclusion of the EPA process.

• 13 January 2013: EU Council reaffirms its commitment to January 2014 deadline for completion of EPAs.

• 13 September 2013: the European Parliament voted to amend the proposal of the European Commission to amend the EPA Market Access Regulation 1528/2007 which sought to prevent countries that have not taken the necessary steps to ratify and implement their EPA agreement as from 1st January 2014. The vote was 322 votes to 78 (with 218 abstentions), in favour of an extension of the 2014 deadline to 2016.

• 5 October 2013: the Council of the EU’s Trade Policy Committee rejected Parliament's amendment on EPA Market Access Regulation 1528/2007

• 1 January 2014: Amendment of Market Access Regulations (MAR) 1528/2007 comes into effect.

Source: Compilation based on review of various documents and press releases of European Commission, ACP Secretariat and others structures of the ACP Group of States

As showcased in Box 2 above, by a unanimous decision, the EU Foreign Affairs Council approved the “EPA negotiation mandate” for the European Commission on 17 June 2002. Official EPA negotiations subsequently commenced on 27 September 2002 in Brussels, with the aim of reaching a conclusion by the end of 2007 at the latest. However, as indicated already, those negotiations are to date not concluded. On the basis of the empirical evidence of the EPA negotiations and its outcomes above, the research problem of the thesis is presented below.

1.1. Research Interest: Twofold

Issues that generate the research interest of this study could be grouped into two main areas. Firstly, how an economically and politically powerful EU would be seen to be “struggling” to reach a conclusion of international trade agreements with a supposedly economically and politically “subservient” ACP Group and regions.

Secondly, on the basis of the evidence of the EPA negotiation processes and

outcomes, it is assumed from the onset that “conventional” theories of IR and EU

22

studies could not possibly offer convincing explanations to the phenomenon. If so, could negotiation theory thus come to the rescue? These twofold research interests are further elaborated below.

Is there a limit to EU’s negotiation power and leverage?

It has been argued that, once the EU has successfully established a common market and member countries have transferred powers for international trade negotiations to the European Commission, the EU would normally easily conclude trade negotiations with third parties (see Dür and Elsig 2011; Larsén 2007a, b, c;

Meunier 2005a; Meunier 2000, 2007; Meunier and Nicolaidis 2005; Meunier and Nicolaidis 2006; Nicolaidis 1999; Pollack 2003a, b). This proposition assumes effective internal decision-making processes within the EU. Similarly, that proposition alludes to the general structural theoretical assumption that, as a stronger international player with asymmetrical “structural power”, and a huge market incentive, the EU would quickly “extract” agreements from relatively and structurally weaker third parties (see Buzan 2009; Galtung 1964, 1971; Glaser 2003;

Guzzini 1993; Hills 1994; Keohane 1993; Mearsheimer 2006; Waltz 2000; Williams 2014).

In other words, from an international political economic perspective, the structural and economic advantage the EU has over the ACP regions would suggest that it has a lot of leverage with them and could thus dramatically influence trade negotiations such as the EPAs with them in line with its wishes. This view of EU’s influence globally as an “actor” is contended by Bretherton and Vogler (1999, 2008).

In their view, EU is a “sui generis” actor in global politics that has the “presence”

(ability to exert influence beyond its borders); has the “opportunity” (factors in the external environment that enables or constrains actorness); and has the “capability”

(the ability of internal policies and context to generate external response by third parties who are affected) (see Bretherton and Vogler 2008:404-407). These characteristics of the EU would thus make it influential in international trade and political negotiations.

However, pondering over the processes of the EPA negotiations with the ACP

regions and countries, and the outcomes so witnessed, cast doubts on the veracity of

such assumptions about the EU’s influence and capabilities on the international

23

stage. In some cases, it has taken over ten years of negotiations – several years after the original deadline for the conclusion of the agreement – and resulted in a watered- down version of the proposed EPAs. Article 37:1 of the Cotonou Partnership Agreement (CPA), which serves as the legal basis for the EPA negotiations, reads;

“Economic Partnership Agreements shall be negotiated during the preparatory period which shall end by 31 December 2007 at the latest. Formal negotiations of the new trading arrangements shall start in September 2002 and the new trading arrangements shall enter into force by 1 January 2008, unless earlier dates are agreed between the Parties (ACP Group of States and European Community and its Member States 2000).

That Cotonou provision reveals that it negotiations have exceeded the initial 2007 negotiation deadline by more than eight years, and yet the EU’s EPA negotiations with the West African region, for instance, have not concluded. Similarly, other regional EPA negotiations are still ongoing. This empirical fact that full regional agreements with the majority of the ACP RECs are yet to conclude in the face of the EU’s asymmetrical power calls for academic enquiry. The reasons for such different negotiation outcomes warrant a rigorous analysis – and that is the first part of interest in this dissertation research.

In order to unravel this research puzzle, seeing the limitation of the EU’s structural and normative power in explaining the EPA negotiation outcomes, a consideration of “other” theoretical and conceptual framework is warranted. That consideration leads to the contemplation of the extent to which a negotiation theoretical framework would offer a more robust explanation, as briefly discussed below.

How does Negotiation Theory help to Explain EPA (International Trade) Negotiation Outcomes?

Having called into question the plausibility of “conventional” EU-centric theories and concepts used in studying the EU’s role in the world to explain the EPA negotiations outcomes puzzle, the second research interest area of this study investigates the extent to which negotiation theory helps to explain difference in negotiation outcomes, such as the outcomes emerging from the EPA negotiations.

In studying international trade negotiations such as the EPAs between the EU

and the ACP Group, scholars allude to a number of factors in a continuum which

24

have potential to contribute to both the processes and the outcomes. Whereas some negotiation scholars consider the evaluation of the often concealed interests of parties against their publicly stated negotiation positions (see Katz and McNulty 1995; Sebenius 1983; Stern and Ward 2013), and/or power relations between parties (see Dinar 2009; Zartman 1971) as an approach to explain international negotiations;

others focus instead on bargaining or negotiating strategy and tactics used in the negotiation (see Elms 2006; Kim 2004; Odell 2002; Shell 1999). Alternatively, some scholars review the role of alternative(s) to the proposed agreement – what is conceptualised as Best Alternative to the Negotiated Agreement (BATNA) as a means to understand the negotiation outcome (see Fisher and Ury 1981; Odell 2002;

Wheeler 2002). Moreover, the negotiating contexts (both internal and external) (see Crump 2011; Weiss and Bedard 2000) and the extent to which the issues of negotiation are linked with other issues of interest to the negotiation parties (known as issues linkage) (see Poast 2012; Poast 2013; Weber and Wiesmeth 1991) are sometimes the focuses of analyses in negotiation studies. This is just to name a few of the research variables that are usually the focuses of international negotiation studies.

Indeed, the literature shows a myriad of variables that are analysed in the continuum in order to offer explanations to negotiation processes and outcomes. That situation also means that a given negotiation outcome could be attributable to several factors as acknowledged by Crump: “The outcome of a single negotiation can have multiple explanations depending on the variables selected for analysis” (Crump 2011:197). The second area of research interest in this study is therefore to determine the extent to which three purposefully selected variables of negotiation theory (indicated below in section 1.3 and elaborated in chapter 3) could help to explain the different EPA negotiation outcomes between the EU and its ACP regional counterparts.

1.2. Research Questions

As described above, the different EPA negotiations outcomes between the EU

and the ACP regions raise a number of questions. However, given the analytical

focus of this study, a dominant research question that is addressed is:

25

Under what conditions are Economic Partnership Agreements between EU and the ACP Regional Economic Communities concluded?

This main research question is further broken into two parts based on the different EPA negotiation outcomes witnessed since the negotiations commenced:

I. Why did the CARIFORUM-EU EPA negotiations conclude?

II. And why are the West Africa-EU EPA negotiations not concluded?

1.3. Research Design and Variables

Comparative Case Study

To answer the main research question and its two parts, a choice is made to systematically study two of the regional negotiations that are arguably most curious – The EU-West Africa, and EU-Caribbean Forum EPA negotiations respectively.

5The two cases have been selected because of the variation in their Dependent Variables – although in some sense there also exist variation in their Independent Variables. It is thus important to point out right away that, even though the two regions are compared and treated as “most-similar systems design”, it is admitted that the two, as in a real world situation, are not perfectly similar cases.

The two regions are selected for study based on their difference in EPA negotiation outcomes. On the one hand, the Caribbean Forum was the first and is the only ACP region to have concluded a full and comprehensive regional-level EPA with the EU. As the only region to have concluded the EPA in this case, it is academically curious and, policy-wise, it is relevant to study why this was the case.

On the other hand, West Africa (ECOWAS) has not concluded a regional-level EPA with the EU. Moreover, ECOWAS is the most significant trading bloc in the ACP Group for the EU, based on trade value and volume, as exemplified by the following statement of the European Commission;

“Of the ACP regions negotiating EPAs, West Africa is the biggest in terms of trade, accounting for over 40% of all EU-ACP trade” (European Commission 2005d:7).

5

As hinted above, there are seven ACP regions negotiating EPAs with the EU. However, examining

all of them into details goes beyond remits of this limited Ph.D. research. As such two most curious

regions are selected for extensive analysis.

26

Trading relations between EU and ECOWAS are thus important to each other as could be further seen in Box 3 below. Bilateral trade between the EU and ECOWAS around the time when EPA negotiations began was around €25 billion per annum.

Recent statistics from the European Commission (2015) still show West Africa as the most important trading partner of the EU among the ACP group. That significant trade position of West Africa in relation to the EU and vice versa has not changed to date.

6Source: European Commission (2005d:7)

It is thus a considered opinion here that, a study of the behaviour and preferences of ECOWAS, as the most important ACP region to the EU and vice versa, and the curious case of the Caribbean Forum as far as the negotiations of the new reciprocal EPA trading regime is concerned, will offer interesting academic, political and policy lessons for both the ACP Group and the EU as well as other interested stakeholders in international trade negotiations (see section 4.2 below for further discussion on the case selection). It is thus also assumed that the research findings from those two case studies could be generalisable to the other ACP regions and possibly beyond. A

6

European Commission 2014 trade statistics show that, “West Africa is the EU's largest trading partner in Sub-Saharan Africa and represents 2% of EU trade (2.2% of EU imports and 1.8% of EU exports). The EU is West Africa's biggest trading partner, ahead of China, the US and India: the EU accounts for 37.8% of West Africa's exports and 24.2% of West Africa's imports. In value, EU – West Africa trade amounts to € 68 billion, and West Africa has a trade surplus of € 5.8 billion” (See European Commission. 2015b:4)

The EU is West Africa’s leading trading partner, accounting for almost 40% of the region’s trade. Bilateral trade between the EU and West Africa has recently totalled about €25 billion a year. The region’s exports to the EU totalled €10.5 billion in 2004. The main categories of exports were minerals (fuels accounting for 43%, iron 3%, aluminium 2% and gold 1%), agricultural products (cocoa 19%, fresh fruit 3%), fishery products (5%) and forest products (timber 2%, rubber 2%).

In 2004 the EU exported goods worth €12.1 billion to West Africa (including electrical equipment, energy, transport equipment, medicines and dairy products).

Of the ACP regions negotiating EPAs, West Africa is the biggest in terms of trade, accounting for over 40% of all EU-ACP trade.

Box 3: Bilateral trade between EU and ECOWAS, 2005

27

detailed overview of the two regions and their relations with the EU as well as their EPA negotiation processes are discussed in Chapters 5 and 6 respectively. Now the Dependent and Independent research variables of the study are presented below.

Dependent Variable

On the basis of the research question above, the Dependent Variable (DV) of the study is the outcome of the EPA negotiations between the EU and the ACP regions, thus dichotomously explaining when the agreement concludes and it does not. This scenario is depicted in the pictorial diagram below;

Source: Author’s own illustration.

On the other hand, the Independent Variables (IV) of the study, deduced from negotiation theories, are presented below.

Independent Variables

Among several possible explanatory variables (Independent Variables) inferred from Negotiation Analytical Approach (negotiation theory), guided by the knowledge and evidence of the EPA negotiation processes and outcomes, three are identified as most plausible in helping to answer the research question as stated above.

EPA negotiations Outcome

(DV)

Outcome I

EPA negotiations concluded (with implementation started)

Outcome II

EPA negotiations not concluded

(implementation still pending)

28 They are:

I. The presence or otherwise of a Best Alternative to Negotiated Agreement (BATNA) to negotiating parties.

The thesis identifies availability or otherwise of a BATNA as an important explanatory variable to the outcome of the EPA negotiation outcome.

II. Negotiation strategies and tactics used by the negotiating parties

A second explanatory variable used in the thesis is negotiation strategy and tactics that were adopted by the negotiating parties in the course of negotiations.

III. Issues linkage strategy

The third and final IV used to explain the dependent variable (the outcome of negotiations) is the role issues linkage approach plays in negotiating outcome.

The relationship between the three IVs is depicted in the diagram below:

Source: Author’s own illustration.

These three Independent Variables are in no way exhaustive but on the basis of the initial evidence gathered on the subject of EPA negotiation, they are considered the most plausible to offer an explanation to the international trade negotiating outcomes witnessed between EU and third party Regional Economic Communities among the ACP Group. Again it must be pointed out from the onset that the three IVs are not actually independent of each other. As is the practice in negotiation analysis, analysts usually consider the negotiation variables in a continuum due to their interrelationship (see Sebenius 1984, 1992; Wheeler 2002). This means, in the real

Negotiation EPA Outcome

(DV)

BATNA (IV i)

Negotiation Strategies/Tactics

(IV ii)

Adoption of Issues Linkage

Approach

(IV iii)

29

world, that the three IVs are not supposed to compete but complement each other to offer a robust explanation for the negotiation outcome. In this study, however, an attempt is made to design and delineate them as “independent” conceptually, to offer a clear line of analysis. Further discussions of the IVs are discussed in Chapter 3 below.

1.4. Relevance and Implications of Study

As shown above, this thesis has been designed to investigate the reasons for the different outcomes of the EU’s EPA negotiations with the ACP Group, comparing the cases of CARIFORUM and ECOWAS negotiations. This subject of study is highly relevant for: diverse stakeholders ranging across the EU and the ACP Group policymakers, and interested citizens and corporations; stakeholders within international trade policies; as well as international development policy practitioners and global politics academics.

First and foremost, studying the EPA negotiations is important because its processes and outcomes have strong implications for EU relations with the ACP Group now and in the future. The transition to and the inception of the EPAs regime after the demise of the unilateral trade preferential regime contains within it the possibility to enhance or mar development efforts in the ACP countries – consisting of mainly poor and underdeveloped economies. Considering the contentious nature of the negotiation so far, its outcome will have either positive or negative implications for EU-ACP relations, which have been courted for several decades.

Secondly, the new EPAs proposed by the EU, purport to go even beyond current multilaterally agreed trade regimes under the WTO. In this way the EU is seeking to shape global trade governance in an unprecedented manner through bi- regional and bilateral agreements. Therefore by understanding the EPA negotiation processes and outcomes as pursued in this study, stakeholders could get to know and understand the invaluable lessons and implications they have for global trade governance.

Thirdly, this study, by seeking to test existing hypotheses in the field of

international (trade) negotiations, will contribute to validating assumptions of

negotiation theories and hence make academically relevant contributions to that

specific field as well as in Political Science and International Relations in general.

30

As hinted above, the focus on explaining bi-regional international trade negotiation outcomes involving EU and ACP regions based on negotiation theory, and the finding that the outcome of negotiations does not only depend on the EU’s structural power would be a departure from the popular assumption in European studies literature. This is the case because the “conventional” approach has been to explain negotiation outcomes by assessing the predominant role of EU in such international negotiations with partners (leaving out the perspective of those partners) (see Dür and Elsig 2011; Larsén 2007a, b; Meunier 2005a; Meunier 2007; Meunier and Nicolaidis 2005; Nicolaidis 1999; Pollack 2003b).Therefore, a general finding that the outcome of international trade negotiations (EPAs) involving the EU and a third party depends on: whether or not that party has (a) better alternative(s) to what EU proposes; the kind of negotiation strategies pursued by both parties; and the application of issues linkage technique; would be unique to this study. That finding is especially relevant when viewed in the context of the dependent relationship that has existed between the ACP countries and the EU, where the former is expected to be subservient to the later. The next section outlines the thesis structure, which has been designed to address the research question posed in this study.

1.5. Thesis Structure

This chapter (1) has given the general introduction of the thesis. It has described the background of the thesis, indicated the research interests and the research questions of the study. It has also briefly presented the research design and dependent and independent variables. Below is an indication of the subsequent chapters of the thesis and how they have been consistently arranged to address the main research questions.

Chapter (2) highlights the existing literature on the EU as a global trade actor, EU-ACP (trade) relationships, as well as discussions on new trade policy in the form of the Economic Partnership Agreements.

Chapter 3 presents the theoretical and conceptual framework that is adopted for

the study. It discusses the three elements of Negotiation Analytic Approach (NAA)

and the three hypotheses generated along the lines of the three independent variables

whose explanatory power is tested in this study.

31

The next chapter (4) identifies the research design and comprehensively discusses the methodological approaches used to gather relevant data in the course of completing this research project. It discusses the approach for the verification of data, data analysis. Before conclusion, this chapter discusses the challenges faced in the course of the research and how they have been addressed to ensure a scientifically standardised thesis.

Chapter 5 presents the first case study of the thesis. It introduces the EU- CARIFORUM relations, discusses relevant socio-economic and political features of the region and discusses the state of play of the EPA negotiations.

Chapter 6 subsequently present the second comparative case study of the thesis. The chapter introduces EU-ECOWAS relations, discusses relevant socio- economic and political features of the region and discusses the state of play of EPA negotiations between the two regions.

The next chapter (7) offers a comparative analysis of EPA negotiations between EU-ECOWAS on one hand and EU-CARIFORUM on another. The analysis is conducted at two levels: firstly at the level of all-ACP and EU and secondly at the level of the EU and the respective ACP Regional Economic Communities alongside the three independent variables and their correspondent proposed hypotheses.

Chapter 8 presents the conclusion of the study. It summarises the thesis and

presents its findings. It then discusses the theoretical implications of the usefulness of

Negotiation Analysis in this study on macro theories of EU and international

relations studies. It subsequently points out identified areas of similarities in the EPA

negotiations as well as identified contradictions that account for the difference in

outcomes in the two negotiations by testing the stated hypotheses. It discusses the

findings regarding the two ACP regions compared in the study and goes on to

present some future research recommendations. The chapter ends with policy

recommendations resulting from the implications that the findings of this study have

on future bi-regional trade negotiations and the political relationship between the EU

and the ACP Group as a whole.

32

Part II: Literature Review on the EU and the ACP Group of States

33

Chapter 2: European Union’s Trade and Development Relations with ACP Countries; Theory and Practice

The trade relationship between the European Union and the African, Caribbean and Pacific countries dates back to the 1950s. In order to present an overview of the subject of this thesis – analyses of factors leading to different EPA negotiating outcomes between the EU and some ACP Regional Economic Communities (RECs) – there is the need to have an overview of the long-standing relationship between the two main regional parties in theory and in practice. This relationship is largely based on the EU’s global and international actorness and actions. This chapter is divided into three parts. The first part (section 2.1) discusses relevant existing literature on EU’s global (trade) actions. The second part (section 2.2) then discusses the literature, specifically focusing on the EU’s trading relationship with the ACP Group.

Then, the third and final section (2.3) highlights relevant academic and policy debates on the proposed EPA policy and its negotiations.

2.1. Discourse on the European Union as a Global (Trade) Actor

The EU has become a very strong global actor involved in many policy areas and cooperating with diverse kinds of other international players – of which the ACP Group is one – for purposes of political, economic, development and trade cooperation. The EU with its 28 member states constitutes the largest economy in the world with a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita of €25 000 for its 500 million population (European Commission 2015b:2). The EU by extension constitutes the world's largest trading block producing the world’s largest manufacturing goods and services as well as leading in global Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs) (ibid.). It is also known that the EU is the most important trading partner for most developing countries; “the EU is the most open to developing countries. Fuels excluded, the EU imports more from developing countries than the USA, Canada, Japan and China put together” (European Commission 2015b:2).

The evolution and prominence of the EU globally as a phenomenon has

attracted quite extensive attention among political scientists and international

relations scholars. A number of studies have described and analysed the EU’s global

actorness over the years with postulations on how it could become a more effective

34

player on the global scene in the future. As a special kind of actor in the international system, that is neither fully an International Organisation as traditionally known nor a Westphalian kind of state, the EU has for example among others been described as a Civilian Power (Duchêne 1972);

7a Superpower (Galtung 1973);

8and as a Normative Power (Manners 2001, 2002).

9These characterisations are based on perceived behaviours and features of the EU. Without an extensive discussion of that, from the onset it is enough to highlight the fact that, the current study departs from an assumption that the EU is considered as an “actor” (see Bretherton and Vogler 1999; Casier and Vanhoonacker 2007; Howorth 2010; Sicurelli 2009; Sonia and Fioramonti 2009) with some kind of “identity” (Manners and Whitman 1998;

Whitman 1998) at the international level. It is that perspective that forms the basis and background for understanding the Union’s negotiations with other international actors such as the ACP Group of states. While, discussing all the various forms of EU actorness at the global level is not the focus of this study, the Union’s activities and policies in the trade policy area are of interest.

In relation to the literature on global “identity” and “actorness” of the EU pointed out above, there has been much more academic discourse on the policy goals of the EU at the global level. In the trade policy area, where the EU is conspicuous globally, the literature is prominent on the Union’s promotion of trade liberalisation in the world (Dür and Zimmermann 2007; Jones 2006; Smith 2011). This academic discourse on the EU’s global trade aims is relevant to discuss in this Chapter as it is this agenda that serves as the background and directly explains the proposals of EU as enshrined in the EPA negotiations with the ACP group of states. Of course it is no secret that from the early stages of its development, the EU has been committed to facilitating global trade liberalisation and since the beginning of the 21

stcentury the

7

By describing the European Community as a Civilian Power, Duchêne saw that the EU was not going to adopt the traditional state’s method of exerting military power in the international system. Rather it was largely to utilise non-military procedures and instruments to achieve its goals in the world.

8

On the other hand, by describing the European Community as an emerging Superpower, Johan Galtung described the creation of the Community as an attempt to establish a “Eurocentric world”

with its centre in Europe and a “unicentric Europe” with its centre in Western Europe (ibid.). In hindsight, looking at how the EU has evolved over the years, that prediction of Galtung is yet to come true.

9