Südasien-Chronik - South Asia Chronicle 9/2019, S. 51-82 © Südasien-Seminar der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin ISBN: 978-3-86004-343-1

51

Changing Imaginaries of Geographies and Journeys in Kumaun & Tibet

VASUDHA PANDE

VASUDHAPANDE55@GMAIL.COM

KEYWORDS:KAILASH-MANASAROVAR,NANDA DEVI,MERU,STRI-RAJYA,CINA-

ACHARA

Part I: Geography and genealogy of the Himalayas and Trans- Himalayas

A geographical imagination of the modern world through cartography and map-making invariably constitutes regions through the disciplinary logic of physical features. Himalayan studies began with this perspec- tive and, the Survey of India exercise (nineteenth to the early twen- tieth century) mapped the entire Himalayas. Two ways of classifying the Himalayas became popular, the longitudinal and latitudinal. The latitudinal found the fold mountains at their lowest in the Shivaliks, gradually increasing in altitude in the middle Himalayan ranges with the highest at Himadri, (snow-covered) and beyond to the trans- Himalayas (Burrard 1933: 279-98). Another way of demarcating this rather long belt of mountains was to divide the Himalayas into river systems—Indus, Sutlej, Yamuna, Ganga, Kali, Karnali, Kali Gandaki and Brahmaputra. It divided the Himalaya into West, Northwest, Central and Eastern. Surveyors also noted and wrote extensively about the Trans-Himalayas, contiguous to the north with the Himalayas.

Though the trans-Himalayas were described in earlier surveys it was Sven Hedin, who popularised the term and brought it into prominence in the early decade of the twentieth century.

52

Figure 1

Source: Burrard G. S. & H. H. Hayden. 1933. A sketch of geography and geology of the Himalaya mountains and Tibet. Delhi: Manager of Publications.

Figure 2

Source: Burrard 1933: 127.

53

The northern boundary of Kumaun which was constituted by Western Tibet (broadly known as trans-Himalaya) generated a great deal of interest. The East India Company and its successor state were curious about the Central Asian and China connections. Travellers, explorers and administrators made forays across the Himalayan passes and described these journeys. In the nineteenth century, difficult access made the journey adventurous, but the terrain was only part of the problem. Tibetan authorities guarded the passes zealously and snea- king in disguised as pilgrims added to the overall excitement. Brian Hodgson, Resident at the Kathmandu court, produced a hypothetical map of this region in 1848.

The services of local Kumauni Bhotias (traders and pastoralists of the upper tracts) were used for state-sponsored surreptitious surveys of regions to the North. The ratification of a treaty with Tibet after the Younghusband mission made it easier to travel in the 'Roof of the World' and C. A. Sherring was the first District Commissioner of Kumaun to travel in Western Tibet. However, it was Sven Hedin’s grit and dexterity that provided a full and informed picture of the topo- graphy of the region in the famous three volumes entitled Trans- Himalayas (I, 1907; II, 1909; III, 1913 Nature January 27, 1910, 367- 9). By the early decades of the twentieth century, the British Empire touched Tibetan territory at three points: Spiti in the Kangra district of Punjab, British Garhwal and Kumaun and Assam at the point that the Brahmaputra entered India (Sherring 1905: 1)

54

Source: Sherring. 1906. Western Tibet and the British borderland: the sacred country of Hindus and Buddhists. London: Edward Arnold.

British Imperial control of Kumaun Division, in 1815, (which was constituted by the two districts of Kumaun and Garhwal, between the Tons and the Sarda (Atkinson II 1884: 268), recognised its mountain- ous terrain and administered it as an Extra-Regulation Tract. During the nineteenth century, administrators like Traill, Batten, Beckett, Ramsay, Atkinson and Goudge1 constructed a narrative around its cultural distinctiveness, premised upon its mountainous topography. In the early decades of the twentieth century, Grierson ratified this by regarding Kumaun and Garhwal as two language formations of Central Pahari. By recognising imperial boundaries as cultural, he made the Kali the dividing line between Nepal and the Empire.

However, British administration, with its focus on revenue genera- tion and the need for connection with the Imperial economy produced

55

an administrative system that altered the coordinates of the earlier system. It created a property regime which undercut community net- works and increased land revenue by encouraging the extension of agriculture into the commons and commercialised the use of forest resources. Its new initiatives eroded the concept of altitudinal zonation, known as 'verticality' in Himalayan historiography, which characterised the mountain economy (Rhoades & Thompson 1975:

539). It was premised upon the vertical oscillation of cultivators, herders and beasts following the vicissitudes of climate to exploit niches at several altitudinal levels. It was the product of a long histori- cal process, which not only knit different altitudinal zones into an integrated economic unit but also accommodated a variegated use of natural resources. Interactive networks spread from the Tibetan plateau in the Trans-Himalaya across the alpine pastures to the middle mountains (through an exchange of grain for salt). Traders and pastoralists migrated to higher locations of the alpine grasslands and beyond to the trans-Himalayas with animals in summer and to sub- Himalayan residences (Terai) for trade-in winter. They connected Tibet in the north to Kashipur in the south through trade in salt, grain, cloth and wool.

The middle mountains (with forests of oak and pine) also did not have fully sedentary peasant populations. Cattle were moved to places where fodder was available resulting in high mobility. Below the middle mountains was the Bhabhar, a dry patch where the water disappeared into the shingles. This was inhabited only in winter when entire popu- lations moved to the Bhabhar to feed their cattle and produce a crop.

A little lower than the Bhabhar and the plains further south was the Terai, where the water resurfaced producing dense undergrowth. This region was hot and malarial and inhabited only in winter. The burning of grasses for luxuriant growth was a practice in the Terai and provided livelihood possibilities in winter to traders cum herders (Bhotias) from the upper Himalayas, and peasant cowherds from the middle mountains.

A crucial external factor in Himalayan and Trans-Himalayan linkages were the peripatetic ascetic traditions. They were the only group who had the right of access to the Trans-Himalayas, and from a very early period, they acted as transporters of high-value goods. The ascetics were also kingmakers in various mountain principalities because of their martial skills. Mathas were given revenue-free grants for their upkeep. In the nineteenth century, the East India Company and the colonial state made a special effort to manage and reduce the power

56

and authority of these groups, but they continued to play an essential role in social and religious life.

How were mountain spaces organised in the pre-British world of Kumaun and Garhwal? According to Prayag Joshi, in Kumauni stories journeys were organized around the latitudinal levels and the movement shifts from the Piyuli Bhabhar (Shivaliks) to Nangar (middle Himalayas), to Baruli Bhotant or Bugyali Pradesh, (bugyal/alpine meadows) and beyond the Himalaya to the yellow, green, red, black, white, blue and ice sagar (oceans) (P. Joshi 1990: 17). The trans- Himalayas are described in great detail in the Brahma Kanwar story where after crossing bugyal country, they reach Tundra country where people live on the meat of deer and yaks. From there they proceed to Horse face country, horse face country to Dogface country and then beyond to the One Eared country. From there to Lampak country where live the One-Legged race, and eventually they reach Bhairon Bugyal in Mahacinadesha.2 If the descriptions of the movement further north are filled with great detail, so is the movement further south.

Swami Pranavananda’s collection of folk stories3 has a description of Shiva and Parvati looking at Kannauj from their perch in Kailash.

Parvati is so enthralled that she decides to send a gana called Hansiya to visit Kannauj. He sets off from Dubachauri to Hemkund, from Shila Samudra (sea) to Roopkund, to Bagubas, Patar Nachauni, Bedini, Lohajag, Nand Kesri, Narayan Bagar, Rishikesh and Haridwar. From Haridwar to the bamboo Bhabhar, then the Amla (Myrobolan/Indian gooseberry) Bhabhar, Coconut Bhabhar, then to the Khari sea and then Dhola sea to Ayodhya and eventually Kannauj (Pranavananda 1995: 49f.). This upward and downward movement fits into a template of various habitats of plateau, snow mountains, alpine meadows, highlands, valleys, dry Bhabhar, the mal/Terai (wet lowlands) in an oscillating circuit through the changing seasons.

The changes to this structure, in the colonial period, with roads and railways connecting the Terai, Shivaliks and middle mountains altered the coordinates and modified the interconnections between the various topographical regions. In Kumaun, trade with the trans-Himalayas continued through the Bhotia circuit, but it did not increase in consid- erable measure (Pande 2017: 68-78). Increasingly, colonial concern with land revenue separated the trans-Himalayan and Upper Himala- yan region from the relatively more peasantised middle and lower Himalayan region. The Bhotia trading communities who connected the Himalaya, trans-Himalaya and the Terai were identified as distinct and

57

separate Tibeto-Burman groups. This disarticulation changed the orientation of the Kumaun, and it looked southwards rather than northwards for its sustenance. The new intelligentsia of Kumaun, pro- duced by colonial education (emphasised the Indo-Aryan aspect) and increasingly affiliated itself with North Indian cultural traditions.

The Trans-Himalayan connection, though alive, was now read through a new imaginary, which understood the connection with the Trans-Himalayas in terms of the Hindu pilgrim land of Kailas Mana- sarovar. For British travellers and Indian pilgrims, the journey to Western Tibet became an achievement in itself. Alex Mckay in his book, Kailas histories, argues that Kailas, as we know it today is a modern phenomenon constructed primarily by European administra- tors and cartographers of the nineteenth century. He says that Sherr- ing, in particular, created the understanding of Kailas as the supreme pilgrimage for Hindus and Buddhists. McKay says that this perspective 'removed the site from its Indo-Tibetan cultural context and transformed it into a globalized mountain for a globalizing world.' (Mckay 2015: 425) This understanding resonated with the modern Indian intelligentsia who also made Kailas the focal point in the Trans- Himalaya, which meant that the long historical connection with the Kumaun region was obscured. The only traveller to interrogate this was Rahul Sankrityayana, but his understanding could not displace the dominant view about the connect with Northern India (Sankrityayana 1953: 68-70)

The Bhotias still embodied the living connection between the Kumaun and the Trans-Himalayas, but the Central Pahari people were looking southwards, migrating for jobs and tracing their roots to Maha- rashtra, Kannauj, Jhusi, Anupshahar and other regions of North India (Joshi 1990: 201-44). The idea of this region as the Deva Bhumi of Hinduism also gained traction in the 1930s, and the development of the notion of Char-Dham in the Garhwal Himalayas led to a further disconnect with the Tibeto-Burman Trans-Himalayas (Whitmore 2018:

84-106; Lochtefeld 2010: 203-30; Pinkney 2013: 229-60). As the southern connection deepened the relationship with the Trans- Himalayan lands receded into the background.

The southern affiliations were strengthened in the postcolonial period. During the Indo-China War of 1962, the relatively porous boundary in the North (Trans-Himalaya) was now marked by the ITBP (Indo-Tibetan Border Police) and Indo-Tibetan trade through the Kumaun Division ceased. The cessation of Indo-Tibetan trade was a

58

loss of livelihood for the Bhotia traders and resulted in a complete disruption of the integrated Himalayan system. A decade later, the Chipko Movement created a storm by contesting timber extraction by North Indian capital. The agitation for Uttarakhand as a separate state (from Uttar Pradesh) which gained momentum in the 1990’s identified a region which reproduced imperial boundaries by separating Kumaun and Garhwal (Uttarakhand) from Nepal in the East, Himachal in the west and Tibet or Trans-Himalayas in the North and accepting its integration with North India to the south through the Terai.

In today’s Uttarakhand, cultural politics is determined mainly by such demarcations, and the Trans-Himalayan connection is almost forgotten. In 1987, Khemananda Chandola reminded the Paharis that,

The cis-Himalayan territory (Central Himalayan) has been described by various names during historical times and before. It was known as Kulinda Janpad, Kiratmandal, Khasmandal, Uttara- khand and Garhwal-Kumaon. Similarly the trans-Himalayan territory is known by a number of names, such as Himavat, Su- varnagotra, Suvarnabhumi, Shan- shung, Guge, Hundes, Ngnari- kor-sum and Western Tibet [...] The trans-Himalayan province of Ngnari-kor-sum consists of four Dzongs (counties) viz., Purang, Dapa, Tsaprang and Rudok […] The territories merge into each other, not only geographically, but ethnically, historically, culturally and economically also. The relations between the two territories go back to the time of the Puranas, Mahabharat and even earlier. (Chandola 1987: xi)

A close reading of Kumauni Literature and History also suggests a familiarity with the Trans-Himalayas. This paper explores how stories about the Trans-Himalayas reveal an intimate connection which suggests another genealogy.

Part II: Trans-Himalayas in the High Traditions: Sanskrit and Brahmanical

In the early decades of the nineteenth century, in the Kumaun Division of the British Empire, two cultural traditions existed—the first was a scribal manuscript culture of Sanskrit and the local languages written in the Devanagari script, the other was a bardic and oral tradition. The writing was inscribed either on metal (copper plate) or stone or written on Pahari paper. The Gurkha Empire (late eighteenth and early nine- teenth century), which controlled both Kumaun and Garhwal and extended up to the Sutlej river sent written instructions to its various functionaries in different parts of the Empire with the famous lal mohar

59

(red seal). The upper castes—Brahmins, Thakurs and Kayasthas dominated the manuscript tradition.

Atkinson’s great reverence for the Puranas and his extensive reference to their geography, (along with his complete myopia about oral traditions) may be attributed to Rudra Dutt Pant making available a manuscript version of the Manaskhand (in Sanskrit). In the Gazetteer (1884) Atkinson provides the historiography of this text. He studies the geography of the Vedas, where he finds few scattered references to the Himalayan Mountains. Then, in the Itihas period, he finds the mountains are prominent, and throughout the Mahabharata, the Himalaya is considered holy worthy of pilgrimage, as the well- loved home of the gods (Atkinson 1884, vol. II: 281-8).

By the Puranic period, 'the North' is fully sanctified, probably because of the Himalayas. But Atkinson provides an important insight into the cosmogony of the Puranas and the significance of the Himala- yas, which he connects with the geography of northern Kumaun and the adjoining part of Tibet. Brahma formed seven island continents Jambu, Plaksha, Salmali, Kusa, Krauncha, Saka, and Pushkara, and separated them from each other by the seas. There is a further division of the Jambu Dvipa into nine regions and at the centre of this is Meru, circular in shape, which forms the germ of the lotus earth (the earth that emerges like a lotus on a stalk from the navel of Vishnu). By locating Meru in the Trans-Himalayas Atkinson, validates the Manas- khand. He says,

Meru in its widest sense embraces the elevated table-land of western Tibet between Kailas on the east and the Muztagh range on the west and between the Himavat on the south and the Kuenluen range on the North. It lies between them like the pericarp of a lotus and the countries of Bharata, Ketumala, Bhadraswa, and Uttara Kuru lie beyond them like the leaves of a lotus. In the valleys of these mountains are the favourite resorts of the Siddhas and Charanas and along their slopes are agreeable forests and pleasant cities peopled by celestial spirits, whilst the Gandharvas, Yakshas, Rakshasas Daityas, and Danavas pursue their pastimes in the vales. (Atkinson 1884, II: 290)

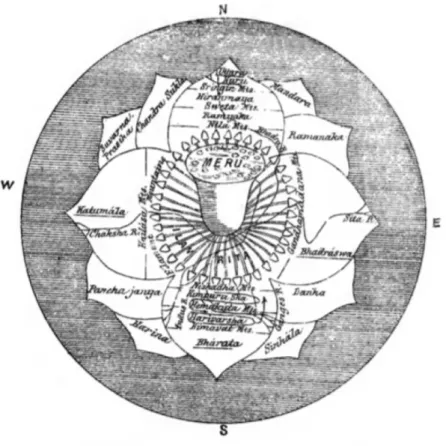

The figure below represents the lotus floating in the sea surrounded by Suvarnabhumi (Tibet/ Trans-Himalayas) and mountains of Lokalok based upon the Bhagavat and Brahmanda Puranas.

60

Figure 4: The figure represents the worldly lotus floating upon the waters of the ocean surrounded by

Suvarnabhumi and mountains of Lokaloka.

Source: Atkinson 1884, Vol. II, Part 1, 291.

Atkinson prefaces his notes on the Manaskhand with,

In form and often in verbiage it follows the model of the older Puranas and minutely describes the country from the lake Manasarovar in Tibet to Nanda Devi and thence along the course of the Pindar river to Karnaprayag. From this point the narrative touches the Dhanpur range and thence to the Ramganga and Kosi as far as the plains. Then along the foot of the hills to the Kali, which it follows northwards, winding up in the hills a little to the east of the Karnali. Notes are given explaining all the allusions and identifying most of the places mentioned. The writers have transferred many of the names of rivers celebrated elsewhere to comparatively unimportant streams in the vicinity of celebrated tirthas, and these have in many cases been forgotten or have existed merely as literary fictions known only to the educated few thence one of the main difficulties in identifying the names given here. The work itself is and is deeply interesting as showing the form in which the actual living belief of the people is exhibited.

(Atkinson 1884, II: 298)

61

Atkinson devotes 25 pages to further details about Manaskhand and another 27 pages to Kedarkhand. Interestingly, he puts Nanda Devi in Manaskhand along with Drona (Dunagiri), Daruka Vana (Jageshwar) and Kurmachal (Kanadeo) (Atkinson 1884, II: 312f.). The significance of Atkinson’s long discussion on the Manaskhand lies in the fact that it includes the newly mapped and cartographically transcribed Trans- Himalayas in the sacred geography of an emergent Hinduism.

Over the centuries, it was the sanyasis (Pasupata Lakulisa, the Nath Panthi jogis, Bairagis, Dasnam Sanyasis, Nirankaris, Nanakpanthis), who had connected the Himalayas to North India. The ascetics were traders (of high-value goods) and provided security as militia to the small principalities (Baisi, Chaubaisi, Thakurais) of the highlands.

Culturally, the ascetics were an integral part of hill society, and according to traditional lore, they were the only groups who were feared by Trans-Himalayan bandits (Badri Shah 1938: 16f.). Kumauni and Garhwali folklore is replete with stories about individuals who crossed the passes donning saffron robes and disguising themselves as ascetics (Meissner 1985: xii). The Manaskhand probably originated as an attempt by the Dasnami Sanyasis to establish monopolistic control over this route, rich in minerals, crystal, precious stones and gold.

British rule however systematically reduced their role by denying jagirs (revenue-free) and gunth (revenue-free lands to temples and monastic institutions). Though local jogis (naths and bairagis) and sanyasis lost their dominance in colonial Kumaun and were gradually relegated to low caste status, pan-Indian connection brought a new wave of ascetic explorers to the Himalaya.

Some of the early writings on Kailas Manasarovar are by members of this fraternity. Bhagwan Sri Hamsa’s description of his journey to Kailas, in 1908, through the Kumaun route was translated from Marathi, and published by the name The Holy Mountain in 1934. It has a lengthy introduction by W. B. Yeats (Sri Hamsa 1934: 11-47) and describes a stay at Mayawati, established by the Ramakrishna Mission.

Another ascetic, Narayan Swami, on a journey to Kailas Manasarovar, was so enchanted by a place near Dharchula that in 1936, he established an ashram here, which would later become the launching point for the Kailas Manasarovar Yatra.

The best known of the ascetics was Swami Pranavananda who first visited Western Tibet and Kailas Manasarovar in 1928. He went in 1935 from Mukhuva Gangotri. In 1936-37 he made the journey again through the Lipu Lekh pass. Two years later, after the publication of

62

his first book, he visited Kailas through the Untadhura, Jayanti and Kingri Bingri passes.4 Pranavananda not only made many visits to the Trans-Himalayas, but he also stayed there many months at a time and on occasion spent an entire year (including winter) in the monastery at Thugholho. Pranavananda endeared himself to the Tibetans by carrying and providing medicines and was fondly referred to as Gyagar Lama Guru, Thugu Rinpoche and Gyagar Amji.

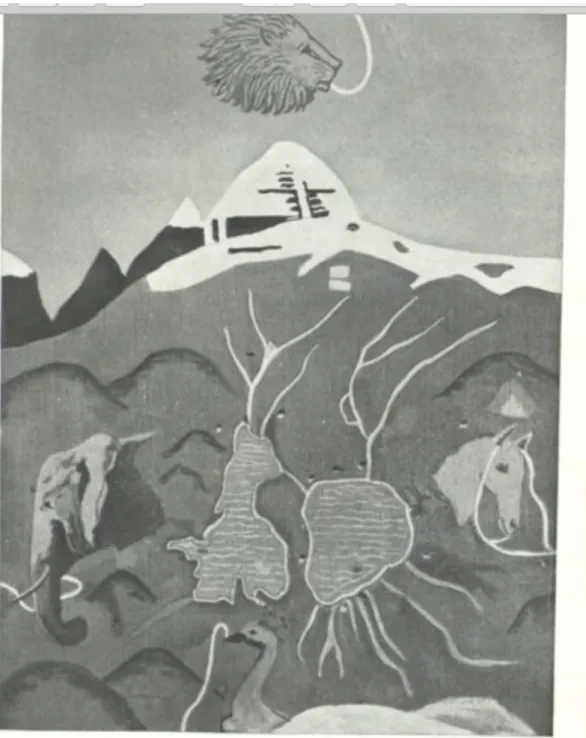

Swami Pranavananda’s close survey questioned many of Sven Hedin’s pronouncements. In particular, he questioned Sven Hedin about the source of the rivers from the Kailash region. Detailed interrogation of Sven Hedin meant that Swami had to prove his geography and hydrology, he made some presentations to the Royal Geographic Society and eventually the Royal Geographic Society and Survey of India accepted his findings and incorporated them in their maps (Prananvananda 1949: 239). What is interesting is that Swami Pranavananda does not refer to the Manaskhand (text), though he refers to two versions of Kangri Karchhak—or Tibetan Puranas on Kailash (idem, 1950: 9), and he illustrates how the Tibetan Kailas Puranas imagine the source of the four rivers that emerge from the Kailas region. The Ganga (Sutlej) from the elephant’s mouth, the Karnali from the peacock, the Brahmaputra from the horse’s mouth and the Indus from the lion’s mouth. A major correction was that the Ganges River is not connected to the Kailas Range.

Though Swami Pranavananda did not refer to the Manaskhand, it remained in the popular imagination and the first history of Kumaun, in Hindi, referred to it in great detail (B. D. Pande 1937: 162-78).

Eventually, the manuscript was edited and published by Gopal Dutt Pande in 1989 by the Nityanand Smarak Samiti, Varanasi. Its Sanskrit dates it to the eighteenth century, and its Puranic allusions for each rivulet in the Himalayas makes it difficult to track, but it continues to feature in the popular imagination of contemporary Kumaun and Garhwal. Though the Trans-Himalayas are not foregrounded in Uttarakhand histories yet Kumauni history and folklore reveal a deep and intimate relationship with Western and Northern Tibet. A close connection with the Trans-Himalayas is the story of Nanda, who is the kula devi (family goddess) of the Katyuris.

63

Figure 5: The source of the four great rivers as described in the Tibetan Sources,Oil painting by E.H.Brewster,

Almora

Source: Pranavananda 1949: 159.

The Pandukeshwar and Bageshwar Inscriptions refer to Nimbar (Katyuri King) as a devotee of Nanda. The Katyuri kingdom and the 900,000 Katyuris who are the protagonists of a large number of folk stories, inaugurate the historical period for this region. It is interesting to note their location, Joshimath in the story and Pandukeshwar where

64

we find the early inscriptions. According to Nachiket Chanchani, Pan- dukeshwar, 'is also the last hamlet in Uttarakhand State in India to host a year-round population on a perilous ancient route that leads from the lush northern plains to Mana Pass, an entry into the frosty Tibet.' (Chanchani 2015: 14-42). The Katyuris emerge around the eighth century at a time when the Tibetan Empire is on the ascendant, connecting Tibet, China, Nepal and India through trade routes (Schaik 2011: 1-40; Beckwith 1987: 37-54). It inaugurates an era of Himala- yan Kingdoms (from east to west) at the entry point to the trans- Himalayas, near the passes (Pande 2018 (a): 19-60; Sankrityayan 1953: 6).

Local traditions believe that Nanda Devi is married to the Yogi of Kailas, Lord Shiva. As the Dhyani or out married daughter, she is celebrated in the bardic traditions, and the Manaskhand also devotes an entire chapter to her5 (Pande 1989: 147-50; Badhwar 2010: 3-27).

The Nandashtami festival celebrates her as one who grants prosperity, but also as one whose curse has to be avoided at all costs. Oakley narrates the story of Traill who removed the Nanda Temple in Almora and lost his eyesight which was restored after he rebuilt the temple (Oakley 1905: 113).

A description of the Nanda Devi festival, in the nineteenth century, is provided by Atkinson. He says that on Nandashtami, every year a procession is formed in Nauti village whose inhabitants accompany the goddess in her palanquin (doli) and proceeds to Baiduni-kund at the foot of Trisul peak. He says that a more elaborate festival is organised every twelfth year, when Nanda’s doli is accompanied by her attendant Latu, and many others from different parts who carry the goddess into the snows, beyond Baiduni-kund and there worship two great stones (sila) glittering with mica which strongly reflect the rays of the sun. On the great mountain, no one is allowed to cook food, gather grass, cut wood or sing aloud, as all these acts are said to cause a heavy fall of snow or to bring some calamity on the party. According to local legend, on these great occasions, a four-horned goat is invariably born in Chandpur and accompanies the pilgrims. When let loose on the mountain, the sacred goat suddenly disappears and as suddenly returns without its head and thus furnishes consecrated food for the party. Atkinson regrets that he was unable to locate an Upapurana devoted to the worship of Nanda (Atkinson 1884, II: 792f.).

We also have a description of the annual yatra and the Raj Yatra of 1987 in William Sax’s account (Sax 1991: 36-126, 160-201). Rich

65

ethnography is complemented with the folk songs sung during the festival (Sax 1991: 18-35). He records that the festival is celebrated every year with the coming home of all dhyanis or out married daughters and the main event is the departure of Nanda to her husband’s home in Kailash. The enactment of the journey is an emotional affair with women singing songs of farewell and the menfolk escorting the procession to the top of a mountain. (where Shiva is considered to reside). Short, invariably one day, journeys are an inte- gral part of the annual calendar of the residents of the upper reaches of the Central Himalayas. In the Badhan region, in particular, the departure of Nanda is an annual affair. She is dressed as an image in a palanquin and is sent off in an elaborate ritual, that takes about three weeks. The Raj Jatra, organised every 12 years, is a more elaborate affair with a long itinerary. It is led by a four-horned ram especially bred for the occasion, and a large number of palanquins from different locations join the journey to bid farewell to the dhyani. In the Raj Yatra, eventually, it is the ram, saddled with gifts, who goes in the direction of Kailas and the escort party returns home.

Sax’s story in broad outline is not very different from Atkinson’s description, but it is filled with the songs of the women of Badhan, Garhwal. The songs give a different flavour and are about the contrast between the green Himalayas and the barren but rich in mineral wealth, country of Nanda’s husband. No birds visit Nanda in Kailash, and it is sparsely populated. But ironically, Nanda visits her mait or natal home before the harvest, and the mother laments that there is no grain though Nanda is happy with the berries and forest produce. In Pranavananda’s version Nanda brings prosperity to her foster family when she is discovered in a gold mine (Pranavananda 1995: 7f.). So clearly, the Nanda story also reiterates the ancient connection between the trans-Himalaya and Himalayas about mining gold. Importantly, in every telling, Nanda travels northwards (Trans-Himalayas) to the epic point which is her than or her place of residence.

William Sax admirably demonstrates the overlay of a patriarchal world view in the songs of Nanda Devi. He suggests that the story of Nanda,

Replays the attempt to show that because of their divergent interests, men and women have significantly different inter- pretations of shared cultural assumptions regarding places and persons; that the cult of Nanda Devi articulates this difference in an especially acute way; and that the goddess's pilgrimages

66

ultimately "resolve" the conflict by reproducing extant relations of male domination and female subordination. (Sax 1990: 491-512) Though Sax suggests that the Nanda story could be linked historically to local marriage customs, based upon bride price, he does not develop this argument, probably because in contemporary Uttarakhand the tendency is to proclaim a Brahmanical world view (Pande 2015:

56-69). In the Pranavananda version Hemant Rishi does not pay bride price but gives labour service. Bride price may help in understanding the prolonged affinity to the natal home and the concept of the Dhyani.

We would suggest that the story be read historically and be linked to matrilineal practices of the Himalayas and Trans-Himalayas probably stemming from ancestors associated with the matriarchate, Stri Rajya (Kingdom of Women). Traces of matrilineal practices are found in the Himalayan region in history and oral traditions. Romila Thapar notes, 'the Buddhist literature of the post Buddhist period when speaking of the origin of the tribes of the middle Ganges plain and the Himalayan foothills has unmistakable references to the matrilineal system.' (Thapar 1979: 308) The Kuninda coins (100 BCE-300 CE), the Lakha- mandal Inscription (500-600 CE)6, and the copper plates of the Khasa Kingdom (Adhikari 1997: xxxii-xxxix) also suggest a matrilineal system. Thapar attributes cross-cousin marriage and bride price also to the matrilineal system. Cross-cousin marriage is practised by a large number of tribal groups in Kumaun, Garhwal and Nepal and bride price prevails in the region even today (Sanwal 1966: 46-59; Lall 1911: 190-8).

The records of the Khasa kingdom and the early Chand records also corroborate matrilineal inheritance (Dabral 2047VS: 207). For example, the copper-plate inscriptions of the Khasa Kingdom use the term "Cheli ko Cholo Bunch" which can be translated as may the daughter’s son consume and enjoy the king’s favour (Adhikari 1988:

xxxi-xxxiii). Traces of matrilocal residence are to be found even today.

M. Krengel found that all festivals required the return of the daughters to their mait (mother’s house). She says, 'at larger festival the female personnel is more or less exchanged […] the men say jokingly at all festivals have been made for the women, so that they can go to their mait.' (Krengel 1993-94: 267-86) She also found that wife taker regardless of age place and occasion touch the feet of wife givers and the ritualised subordination of the wife takers seem to be expressed more readily than in other areas.

67

We suggest that these customs exhibit a radically different under- standing of gender, that is, the relationship between men and women.

This worldview is not premised upon the need to protect women’s chastity (unlike the Brahmanical view) but upon her indispensability as a sexual partner and her reproductive abilities (Joshi 1929: 63f.).

There is much speculation in Himalayan Histories about Xuanzang’s description of the kingdoms of Brahmapura and Stri Rajya. According to some historians, Brahmapura is in Himachal Pradesh, while others suggest it is in Kumaun and some historians locate it in Garhwal. Stri Rajya, to the north of Brahmapura, is broadly identified with Tibet (Asiatick Researches 1825L 48; Xuan, Zang (Hiuen Tsiang) 1906: 165- 205). Atkinson citing Chinese writings locates Stri Rajya, in Northern Tibet. (Atkinson 1884 II: 458f.) whereas Tucci identifies Stri Rajya with Western Tibet primarily because he considers Stri Rajya as synonymous with Suvarnagotra (Tucci 1956: 92-105; Chandola 1987:

40-2; Smith 2001: 465-77)

According to Atkinson, the queen of Stri Rajya was replaced by a king in 742 (Atkinson 1884, II: 459). We can link this to the eighth century Katyuri inscriptions about Nanda and suggest that in the eighth century (when we find the first reference to Nanda) there was also a shift from matrilocal to virilocal and the Nanda Devi festival marks this important transition. The Nanda Devi festival then marks an important event in the history of the region which attests to its close links with the trans-Himalayas.

Part III: The Trans-Himalayas in the bardic and vernacular traditions of Kumaun

The oral traditions were quite diverse—the bards sang rachya (protection and honour) songs for their patrons on special occasions, there were community jagars (woke) with shamanic possession rituals and then there were the epic Bharatas sung for 22 days in winter or on particular festivals. The jangam Nath/siddha traditions were also prevalent and religious ritual blended well with singing and dancing around the dhuni (sacred fire). The bards also sang stories and provided entertainment during communal agricultural operations like transplanting rice. The bardic singers were accompanied by the hurakia (drummer) and by the dhol and damau. Over the nineteenth century as caste profiling (through census and other state taxonomies) became part of popular perception the bards found patrons becoming more conscious of the impurity caused by use of animal hide.

68

By the early decades of the twentieth century, the Das (a special group of bards), who was recognised as a separate category in the Almora 1891 Census, were relegated to the lowest denomination in the caste hierarchy. The ratification of Kumaun Customary Law in 1920, brought tensions around caste to the fore. In 1932, varna (caste) affiliations were endorsed at a public meeting of the Kurmanchal Samaj Sammelan in Almora. The growing pervasiveness of caste was reflected in the public sphere and print media (Pande 2013: 6-9). A journal to promote Kumauni, Achal, emphasised the Sanskrit roots of Kumauni and the intelligentsia downplayed the performative aspects of the bardic tradition. As a consequence, in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980’s anthropologists searching for traditional performers found it difficult to locate the Das- Dholi- Damai, ghantuwas, jagariyas and dungariyas.

A century and a half of high cultural traditions, lack of patronage and downgrading of their vocations had considerably reduced those familiar with what was now relegated as folk and shamanic. In the 1960s, anthropologist Marc Gaborieau (1977) found his informants in Far Western Nepal, and in the 1980s Frank Bernede (1997) eventually chose to work on Far Western Nepal and Eastern Kumaun. Many of the traditional performers came from Western Nepal, across the Kali River, for example Kabutari Devi and the most celebrated folk singer, Jhusia Damai.

The first collection of folklore by E. S. Oakley and T. D. Gairola was published by the Government Press in 1935. Gairola noted that there is no written literature and it has come down by word of mouth from the Hurkias or bards of the region. Himalayan folklore, in English, therefore acknowledged and provided a picture of Baga Hurkia, who was the main informant. In the 1930s, left minded nationalists propa- gated a popular cum folk regional sensibility, P.C. Joshi, Mohan Upreti, Badri Shah Thulgarhia and others consciously transcribed a large corpus of tales in the Kumauni language. This encouraged the intelligentsia to research, catalogue, document and publish Kumauni folk literature (Pande 2018 (b): 145-9). Kumauni and Garhwali literature was rendered textual (not oral) and the paper will examine some stories and legends from these texts for the understanding of spatial categories with special reference to stories about the Trans- Himalayas.

The cosmology elaborated in these stories is different from that in the Puranas. The earth is born from the egg of Soni Garuri (incorrectly translated as vulture, by Gairola) The Garuda is an important symbol

69

in Hinduism, Bon religion and Buddhism (Beer 2003: 74-7) and is found in the Himalayan and trans-Himalayan traditions (Oakley &

Gairola 1935: 171f.). Another common motif in both Tibetan and Kumauni Literature is the reference to Nagas.7 In the Nanda story, the 12 Nagas, are part of Shiva’s wedding procession. E. T. Atkinson suggests that the Nagas were a race of trans-Himalayan origin—who adopted the snake as their national emblem (Atkinson 1884: 373f.).

Interestingly, the Garuda and Naga are an integral part of the Tibetan understanding of Meru Mountain. In the Tibetan tradition, Meru has four ascending tiers—Nagas, Garudas, Rakshasas, Danavas and lastly Yakshas (Beer 2003: 82-4). The significance of Meru, Garuda and Nagas are shared in the Himalayan and Trans-Himalayan literary traditions.

According to Govind Chatak (Chatak 1996: 22-4), Trilochan Pandey (T. Pandey 1977: 234-8), Shailesh (1976: 263-92), and other scholars, Krishna as Nagaraja (snake-king), is popular in folklore. They point out that though traditional stories about Krishna are also known and sung, Krishna figures as a protagonist in local narratives. The most famous story about Krishna as Nagaraja is the conversion of Gangu Ramola. The fort of Ramola is marked by a temple to Nagaraja in Sem Mukhem and is now a well- known local pilgrimage site.8 Local history suggests that Brahmadeva, a Katyuri king, who ruled from Dwarka (Dwarahat) was considered as Nagaraja and the conversion of Gangu Ramola occurred around the twelfth century. In Tibetan and Nepali genealogies Nagaraja is the founding figure of the Khasa Kingdom of Khari9 which also controlled Kumaun and Garhwal/Ramola territory, attested to by the inscriptions at Baleswara Temple (1223 CE) and the trident inscription of Ashokchalla at Gopeshwar (1251 CE) and Barahat.10

An interesting motif of the local stories of Nagaraja is the fatal attraction of the women of Cina and Mahacina (replaced by Tibet in most stories except in those narrated by Prayag Joshi). To bring these women back to the protagonist’s home requires agility (mental and physical) stratagem, magic, ritual and support from friends and kin.

We start with a story about the Katyuri king Asanti referred to by Gaborieau in his Introduction to the reprint of Gairola and Oakley’s book on folklore (Gairola & Oakley 1977: xi-xlviii).11 He narrates how the bards sing the following story about the beginning of the Kingdom of Kumaun:

70

In ancient times, King Asanti ruled over Joshimath. One night he saw in a dream a beautiful Tibetan Princess called Hima Marchi.

He fell in love with her and decided to go and fetch her. His wife Nathva tried in vain to stop him. He took a last meal served by his wife, donned his clothes and left for Tibet. After a long and difficult journey, he reached the palace of Hima Marchi and introduced himself to her parents. They agreed to give him their daughter but asked him to stay with them for some time. One day they put poison in his food; he died; his soul appeared to the god Nar Singh who went to Tibet and miraculously brought him back to life. The god and the king decided to leave immediately this sinful country and travelled together toward Garhwal.

Narsingh went ahead and reached the palace first. He asked for hospitality. Queen Nathva served him a meal. He then insisted on sleeping in the bed of Asanti. But a magical bell was hanging under the bed and it rang. Asanti who was still fifty-two leagues away heard it. He hurried to his palace and seeing a stranger in his bed, thought he was a paramour of his wife. Asanti drew his sword and pierced Narsingh’s thigh. When milk flew from his wound, he recognized the god, threw away his sword and asked for forgiveness. As a punishment he had to abandon Joshimath, which since that time belongs to Narsingh and where a mark of the wound can still be seen on the statue of the god.

Asanti leaves Joshimath, opens up the lake near the Kausani pass above Katyur, the water of which flows out as the river Gomti and here Asanti establishes Baijnath at the confluence of the Ganga and Gomti rivers. How do we read this magical call from the Trans-Himalayas?

Does it suggest that the queen (of maybe Stri-Rajya) has to be won by the brave male protagonist for legitimacy and authority over the kingdom because the motif is repeated in the Ramola stories and figures even in the much later but more famous epic of Malushahi, another Katyuri prince?

Ramola are a genre of love stories about Nagaraja/Krishna, Surju, Brahma, Dudh Kanwar the nine Kanwar brothers/sisters (ubhaylingi, therefore sometimes men, sometimes women) who live in Kalagirikot of Nagalok and are (P. Joshi 1994: ii) connected to Sidwa and Bidwa, the sons of Gangu Ramola through marriage. These stories of love and longing link the Kumaun Himalayas with the trans-Himalayas. In these stories, the male protagonist, invariably of royal lineage, sees or hears about a beautiful woman in faraway Hyundesh, (Chandola 1987: 9f.) Mahachina/ Cinadesa (P. Joshi 1994: iii; Tucci 1956: 92) and despite many warnings from friends and family about the dangers of travel in the land known for its poisonous vapours he sets off to get his beloved. Prayag Joshi’s rendering of the journey from Dwarka, via

71

Ramoligarh to Mahacinadesa is probably the most detailed and is full of adventure, misfortune, obstacles, death-defying magical spells, bravery and success. He says that the Ramolas travel northwards to Nagalok and are helped by fairies (paris). The fairies are sisters of the Ramolas who live in the alpine pastures (bugyals), between Nagaloka and the white ocean. Some of these places are full of gold; others are yellow lakes dripping with pollen. The fairies fly astride the rainbow and on moonlit nights visit the middle and lower mountains. They can take on the form of a man or a woman and the nectar they produce can rejuvenate humans. Ramolas connect with them and travel astride flying horses to cut difficult cross terrain with ease, defying mountains, and sagar/ oceans of ice and water.

On the way to Mahacina, Ramolas first encounter the Ashvamukha (Horseface) country where men have the face of a horse and the body of a man. After that, they reach kukurmukh desh where men have the face of a dog. From the dog face country, they proceed to a country where men have only ek-kaniya (one ear), and from there to lamkanya (long-eared country), where people have such long ears that they double up as bedding and cover whilst sleeping. Then there are the one-legged people before Mahacina can be reached (P. Joshi 1996: iii- v). Also many more oceans yellow, red, black have to be crossed after which the multi-storeyed houses start and that is where the beautiful woman of the protagonist’s dream is to be found, but she is heavily guarded and has to be won through stratagem with the magic of Sidwa and Bidwa. How do we make sense of these stories which sound like fantasy and are filled with magical occurrences?

Prayag Joshi is struck by the literary quality of Ramola poetry. He refers to the imagery of the beautiful Hyunkali, who lives across the seas and is like a lamp that lights up both sky and earth and suffuses the soul of Surju Kanwar (Joshi 1990: ix). Though she lives in the luxurious three-tiered house of Khamjham Huniya, she is limp like the amaranthus (marsa leaf) in her grief for Surju (Joshi 1990: 22).

Govind Chatak argues that in the Ramola Gathas, Krishna is a rasik (passionate hero). He says that the erotic aspect dominates these stories and sexual gratification is the desired goal. He suggests that the glorification of Parkiya (sexual union outside marriage) was a part of medieval bhakti (devotion) and says that the Nagas, Shakas and Hunas gave it a new flavour (Chatak 1996: 22). It is G. Tucci, who identifies Suvarnabhumi, Suvarnagotra, Strirajya and Cina with western Tibet. According to him,

72

Suvarnabhumi refers to the gold mines of which the country is very rich, but most probably the geographical name was Cina (quite different of course from Cina=China) a fact already acknowledged by many scholars and now made certain by our inscription referring to western Tibetan country as Cina, the country Varahamihira quotes alongside the Kirata, Kauninda and Khasa. (Tucci 1956: 102f.)

In this context, Agehanand Bharti’s chapter on India and Tibet in Tantric Literature in The Tantric tradition, (1965: 58-84) provides us with some clues. The development of the Mahacina method of sadhana (practice) appears to be linked to the Nilapatta mountain, (blue mountain) and the blue ritual dress. According to legend, Vasistha, the son of Brahma, practised austerities for many ages but still Parvati did not appear to him. He went to Brahma and asked him for another mantra, or else threatened to utter a terrible curse. His father dissuaded him and said that he should worship the supreme Shakti who is attached to the pure Cinachara. For a thousand years he repeated her mantra but received no instructions whereupon he began to curse the goddess who appeared before him as Kuleshvari. She advised him to go to Mahacina, to become well-versed in her Kula and become a great Siddha (realised soul).

Eventually, Vashishtha was initiated into the Mahacinachara by Buddha himself. This involved the worship of Nilogratara who was born on the lake called Cola on the western side of Mount Meru. A. Bharati identifies Nilogratara with the Hindu Buddhist goddess Chinna-masta, (Split-Head) the goddess who holds her own chopped off head in her hands. If we accept Bharati’s proposition then we find that Nandadevi was probably Tara of the Vajrayana, or Nanda was incorporated into the myth of Chinna-masta.12 Gudrun Bühnemann also locates Maha- cinakrama-Tara (Ugra-Tara) in Pahadi paintings from Garhwal and Himachal (Bühnemann 1996: 472-93).13 What then is the Cinachara/

cina code of conduct? According to A. Bharti, 'the explanation boils down to a hierarchy of spiritual disciplines, the lowest of them being that for "Pashus" (lowly type of aspirants) tantamount to the Vedic ritual, the highest and most efficient being Cinachara involving the use of wine, meat, women etc.' (Bharti 1965: 68) The use of the five makaras and the link of Cinachara to the left-handed rites and Bhota, Cina and Mahacina region is supported by other evidence as well (ibid.: 73).

Cinachara was supposed to guarantee worldly success, without the usual austerities. On the contrary, it advocated the indulgence of the

73

senses. Maybe, for this reason royal lineages adopted it. In this system the human body became the vehicle for the realisation of the ultimate essence. It, therefore, dispensed with an external material image and emphasised the performance of ritual which required only mental images. Quoting a later Tantra Bharti, Shiva tells Parvati that,

by the method of Mahacina results are quickly obtained;

Brahmacina, the celestial Cina, the heroic Cina, the Mahacina and Cina are the five sections or regions; the methods of these have been described in 2 manners as the "sakala" (with divisions) and the 'nishkala' (the undivided). That which is "sakala" is Buddhist and that which is 'nishkala' is Brahmin in its application. (ibid.:

76)

We find that folk memory stores traces of the past, which helps us to link ritual practices of an earlier period with living traditions. Today cinachara would be considered abominable but it helps us to resurrect shared traditions of Western Tibet and Uttarakhand. We will try and

trace this history in the concluding section.

Conclusion Figure 6

Source: Map made by B. S. Mehta for Vasudha Pande.

The first part of this paper shows how the British Imperial system, produced a new spatial imaginary about the Himalayan Mountains

74

through explorations, survey and cartography. Pre-modern Himalayan communities considered the Terai (swamp) in the south as a natural boundary whereas the Trans-Himalayas were regarded as an integral part of the highlands. British rule altered this understanding—it con- nected the mountains and the plains with rail and road networks which made the Terai navigable and made the High Himalayas the natural political boundary. In this re-visioning and re-organisation, millennia- old vertical linkages of different kinds of habitats, which maximised natural resource use over the seasons were disrupted. Revenue and commercial considerations produced new articulations in the agro- pastoral economy of the Kumaun Division highlands. The Trans- Himalayan connection was re-oriented as the Kumaun administrative Division was tied more firmly to the British Empire in India.

The second part explores how the earlier geographical perspective was reconfigured and adapted to new spatial constructs of surveying, mapping and cartography. A Sanskrit manuscript, the Manaskhand Purana which claimed to be part of the Skanda Purana was taken seriously by E. T. Atkinson, author of the Himalayan Gazetteer, who gave it a pride of place in his history of Kumaun. He also linked Manas- khand’s geography to contemporary knowledge of the region. Since many of the Puranic allusions were not easy to decipher, Atkinson found that he was not able to match many parts of it. But the salient points about Hindu cosmology regarding Meru (Sacred Mountain), Jambu-Dvipa and the Trans-Himalayan links were appreciated by British administrators, the new Kumauni and pan-Indian intelligentsia, rendered Kailash Manasarovar a global sacred space. In this process the historical relationship between the trans-Himalaya and Central Himalayas was obscured.

By the closing years of the nineteenth century Vivekananda and Sister Nivedita had popularised the idea of the 'Holy Himalaya'. By the early decades of the twentieth century, because of railway and road connections, sanyasis (ascetics) from Maharashtra (Swami Hamsa), Andhra Pradesh (Swami Pranavananda), Karnataka (Narayan Swami), Punjab (Ram Teertha), Bengal (Ramakrishna Mission), Kerala (Tapovan Maharaj), Bihar (Rahul Sankrityayana) and other regions of India were on the Kailas Manaskhand trail, mapping it in detail and advising pilgrims how to negotiate the terrain and the journey. The relationship between the Central Himalayas (Kumaun & Garhwal) and Western Tibet was now re-ordered in terms of sacred geography, which completely obscured the shared histories of the two regions.

75

This fresh articulation dominated new publications which wrote histories in consonance with British imperial boundaries. Shared cultural practices and lexicons surfaced in the vernacular and bardic traditions, in the way Kailas Manasarovar was understood as sacred space and in the festivities around the local goddess, Nanda Devi.

Contiguity was an essential aspect of the terrain, and the demarcation of difference also underscored a recognition of a shared similarity. The growing emphasis on proximity to the North Indian Brahmanical world view made consciousness of caste more pervasive and eroded the standing of the bards (they were designated to the lowest status because of the use of drums made of animal hide) as repositories of historical antecedents. It also meant a restructuring of family and gender roles by equating polyandry, bride price, levirate, widow remarriage with backwardness.

The transcription and publication of folk legends and stories by the new intelligentsia produced a vast amount of literature. The third part of the essay looks at some of these stories, with particular reference to the stories termed Ramola. These stories are a distinct genre and given their thematic is clearly about the Himalaya and the Trans- Himalaya. These love stories are erotic but are also about vira (brave) heroes and beautiful heroines. The use of poison, magical, physical and spiritual power is integral to the story. Contemporary observers find it hard to identify the locations that are invoked, and many of the scholars have substituted local terms with Tibet. Thanks to Prayag Joshi, we have detailed stories without modification of names of places and an informed analysis providing us with historical clues which we try and unravel.

When we look at the archaeological record, we find evidence of trade linkages within the Upper Himalaya and Trans-Himalaya (Nautiyal & Bhatt 2009: 205-16). This connection was forged very early, by the second millennium BCE. The dates for an agro-pastoral system in Western Tibet, are around 800 BCE. Surveys confirm that the pastures of Tibet are human-made, as are the bugyals of the High Himalaya, replacing forest with grassland, the work of pastoralists.

From the first millennium BCE to 850 CE metal mining and working transformed trade networks. Gold was an important metal, found in Himalayan rivers and also in Western Tibet. Besides gold, copper, iron, lead, were also found in the Himalayas. Gold mines of South Asia were so well known that Herodotus refers to gold-digging ants. We, therefore, find interesting stories about Suvarnabhumi and giant ants who dig out the gold. These are mentioned in Megasthenes Indika as

76

stories about the fabulous races and tribes which resurface in Prayag Joshi’s descriptions. This evidence suggests that places we find inaccessible today were occupied and used as human settlements (Aldenderfer 2013: 293-318).

It was the western and central Tibetan valleys, contiguous with the Central Himalayas, which offered scope for extensive human settle- ment. It is in this area, around the region of Kailas Manasarovar, that research reveals extensive settlements, both sedentary and pastoral, of one of the largest polities that emerged in early Tibet. This was the fabled polity of Zhang Zhung, the nurtured Bon, and controlled a large number of the Trans-Himalayan valleys (Bellezza 2014: 75-297). Tucci says that its southern provinces were vaguely known to India as Suvarnabhumi, Strirajya and Cina when it passed under the rising power of the Tibetans.

The emergence of the Katyuris in the seventh century at the passes to the Trans-Himalayas (in Garhwal) suggests the importance of the connection, and we have already discussed the location of Stri Rajya and speculated on its significance for the Nanda Devi festival. If we consider Zhang Zhung as including Katyuri territory, then we may even suggest the possibility of the marriage of Nanda to the Tibetan Emperor. (A matrimonial exchange with Zhang Zhung was part of the pacification process) After the breakup of the Tibetan Empire, a new era was initiated in Western Tibet. It was established by Nagaraja according to the Dullu Inscription and the Tibetan records. The new state of Ngari Kor Sum was formed which consisted of three circles—

Purang in the south, Guge in the centre, and Rutok in the north (including Ladakh).

The emergence of the Khasa kingdom with its centre in Western Nepal (along the Karnali River) marks an epochal change. It covered a large territory in the Central Himalaya and Trans-Himalaya—Western Nepal, Southwestern Tibet, Kumaon, and Garhwal. The Khasa Kingdom can be regarded as an important development in the history of the region. It is from this period that agricultural productivity increased (with the introduction of rice cultivation) and a shift occurred towards the south and the east. The Khasa Kingdom was Buddhist in the North and Brahmanical in the south. The Cinachara tradition was probably followed in this region, and the Ramola stories of the high Himalayas and trans-Himalayas could be linked to this epoch. We thus note that Himalayan histories are deeply implicated with Trans-Himalayan

77

narratives for around four millennia and the historiography of this connection needs to be elaborated and made visible.

Endnotes

1 R. S. Tolia. 1994. British Kumaun Garhwal 1815-1835. Almora: Almora Book Depot; R. S. Tolia.

1994. British Kumaun Garhwal 1836-1856. Almora, Almora Book Depot; A. K. Mittal. 1986. British administration in the Kumaon Himalayas 1815-1947. Delhi: Mittal Publications.

2 Quite similar to J. W. McCrindle. 1877. Ancient India as described by Megasthenes and Arrian.

Bombay: Trübner and Co., pp. 74-89.

3 Swami Pranavananda. 1995. Uttarakhand ki lok that. Pithoragrah: Edited and published by Uttarakhand Shodh Sansthan.

4 Swami Pranavananda. 1950. Explorations in Tibet. University of Calcutta; Introduction by Syama Prasad Mookerjee and Foreword by S.P.Chatterjee, Head Department of Geography. 1st edn.

1939); F. R. G. S. Pranavananda. 1949. History of Kailas Manasarovar with maps. Calcutta:

S.P.League: with a Forward by Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru, dedicated to His Holiness Sri 1108 Narayan Swami Ji Maharaj, Soosa: Sri Narayan Swami Ashram.

5 G. D. Pande. 1989. Manaskhand. Varanasi, Chowkhamba:Far Western Nepal celebrates her as Gaura (another name for Parvati)

https://www.nepalitimes.com/banner/fasting-feasting-and-festivities-of-gaura [retrieved 09.07.19].

K. Badhwar. 2010. Where Gods dwell. Delhi: Penguin.

6 https://www.asidehraduncircle.in/dehradun.htmlaccessed [retrieved 27.07.19].

7 Robert Beer. 2003. A handbook of Tibetan Buddhist symbols. Colorado: Shambhala Publications, pp. 70-3; D. D. Sharma. 2009. Cultural history of Uttarakhand. IGNCA, pp. 197-214; U. D.

Upadhyaya. 1979. Kumaun ki lok gathaon ka sahityik aur sanskritik adhyayan Bareilly: Prakash Book Depot, pp. 237-41.

8 http://www.meruraibar.com/religion/gangu-ramola-sem-nagraj-temple-ramoli/ [retrieved 31.07.19].

8 A play featuring Gangu Ramola was performed and uploaded on https://youtu.be/BojGPQ9Npvk [retrieved 23.01.17] and reported in

https://rebaruttrakhand.blogspot.com/2017/01/blog-post_23.html [retrieved 31.07.19].

9 Tucci G. 1956. Preliminary report on two scientific expeditions in Nepal IsMEO, Rome; Surya Mani Adhikari. 1988. The Khasa kingdom: a Trans-Himalayan empire of the Middle Ages, Jaipur:

Nirala Publications.

10Atkinson 1884, vol. 2, 512.

11 E. S. Oakley & T. D. Gairola. 1977. Himalayan folklore Kumaon and West Nepal. Kathmandu:

Ratna Pustak Bhandar.

12 Bühnemann 1996: 485.

13Avalon Arthur, 1918 Shakta and Shakti, Chapter Eight Cinacara (Vashishtha and Buddha) https://www.sacred-texts.com/tantra/sas/index.htm [retrieved 16.07.19].

78

Bibliography

Adhikari, Suryamani. 1988. The Khasa Kingdom: a Trans-Himalayan empire of the Middle Ages. Jaipur: Nirala.

Aldenderfer, Mark. 2013. Variation in mortuary practice on the early Tibetan plateau and the high Himalayas. Journal of the International Association of Bon Research, 1, pp. 293-318.

Atkinson, E. T. 1884. The Himalayan districts of the North Western Provinces of India, vol. II. Allahabad: Government Press.

Asiatick Researches. 1825. vol. 15. Serampore: Mission Press.

Babulkar, Mohan Lal. 1964. Garhwali lok sahitya ka Vivechnatmak adhyayan. Prayag: Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, pp. 131-53.

Badhwar, Kusum. 2010. Where Gods dwell: Central Himalayan folktales and legends. Delhi: Penguin.

Beckwith, Christopher. 2009. Empires of the Silk Road: a history of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the present. Princeton:

Princeton University Press.

_____. 1987. Tibetan empire in Central Asia. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Beer, Robert. 2003. A handbook of Tibetan Buddhist symbols.

Colorado: Shambhala Publications.

Bellezza, J. V. 2014. The dawn of Tibet: the ancient civilisation on the roof of the world. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

_____. 2008. Zhang Zhung, foundations of civilization in Tibet, a historical and ethnoarchaeological study of the monuments, rock art, texts and oral tradition of the ancient Tibetan Uplands.

OAW: Verlag des Österreichischen Akademie der Wissen- schaften.

Bernede, F. 1997. Bards of Himalaya, epics and trance music. CNR 2741080 (Le Chant du Monde, Collection of CNRS & Museum of the Man). Paris: CNRS.

Bharti, Agehanand. 1965. The Tantric tradition. London: Rider and Company.

Burrard, G. S. & H. H. Hayden. 1933. A sketch of geography and geology of the Himalaya Mountains and Tibet. Delhi: Manager of Publications.

79

Bühnemann, Gudrun. 1996. The Goddess Mahācīnakrama-Tārā (Ugra- Tārā) in Buddhist and Hindu Tantrism. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 59 (3), pp. 472-93.

Chanchani, Nachiket. 2015. Pandukeshwar Architectural knowledge and an idea of India. Ars Orientalis, 45, pp. 14-42.

Chandola, Khemanand. 1987. Across the Himalayas through the ages, a study of relations between Central Himalayas and Tibet. Delhi:

Patriot Publishers.

Chatak, Govind. 1996. Garhwali Lok Gathayen, Delhi: Takshila Prakashan.

Dabral, S.P. 2047VS Uttarakhand ke Abhilekh evam Mudra. Dogadda:

Veer Gatha Prakashan.

Gaborieau, M., ed. 1977. Himalayan folklore of Kumaon and Western Nepal. Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar.

Hamsa, Bhagwan Sri. 1934. The holy mountain. London: Faber &

Faber.

Hedin, Sven. 1913. Trans-Himalayas, adventures and discoveries in Tibet, vol. III. London: Macmillan and Company.

_____. 1910. Trans-Himalayas, adventures and discoveries in Tibet, vol. II. London: Macmillan and Company.

_____. 1909. Trans-Himalayas, adventures and discoveries in Tibet, vol. I. New York: Macmillan and Company.

Joshi, L. D. 1929. The Khasa Family Law in the Himalayan districts of United Provinces India. Allahabad: Government Press.

Joshi, M. P. 1991. Kumaun Vanshavalis, Myth and Reality. In: M. P.

Joshi, A. C. Fanger & C. W. Brown, eds. Himalaya: past and present, Vol. I. Almora: Almora Book Depot, pp. 201-44.

Joshi, Prayag. 1990. Kumaun garhwal ki lok gathayen. Bareilly:

Prakash Book Depot.

_____. 1994. Kumauni lok gathayen, vol. 3. Bareilly: Prakash Book Depot, pp. 100-28.

Kolff, D. H. A. 2010. Grass in their mouths the upper Doab of India under the Magna Charta 1793-1830. Leiden: Brill.

Krengel, Monika. 2000. Communication and gift exchange between wife-givers and wife-takers in Kumaon. In: M. P. Joshi & A. C.

80

Fanger, eds. Himalaya: past and present, vol. IV. Almora:

Almora Book Depot, pp. 267-86.

Krengel, Monika. 2017. Change and continuity in customs and legal orders Kumaon Himalaya. In: M. P. Joshi & B. K. Joshi, eds.

Cradle of culture. Doon Library Centre and Almora Book Depot, pp. 259-95.

Lall, Panna. 1911. An enquiry into the birth and marriage of the Khasiyas and Bhotias of Almora District in U.P. Indian Antiquary, 40, pp. 190-8.

Lochtefeld, James. 2010. God’s gateway: identity and meaning in a Hindu pilgrimage place. New York. Oxford University Press.

McCrindle, J. W. 1877. Ancient India as described by Megasthenes and Arrian. Bombay: Trübner and Co.

McKay, Alex. 2015. Kailas histories: renunciate traditions and the construction of Himalayan sacred geography. Leiden: Brill.

Meissner, Konrad. 1985. Malushahi and Rajula: a ballad from Kumaun as sung by Gopi Das. Wiesbaden: Otto Harassowitz.

Mittal. A. K. 1986. British administration in the Kumaon Himalayas 1815-1947. Delhi: Mittal Publications.

Review of Sven Hedin Trans-Himalaya, Nature, 27 Jan. 1910, pp. 367- 9.

Nautiyal, K. P. & R. C. Bhatt. 2009. An archaeological overview of Central Himalayas: a new perspective in relation to cultural dif- fusion from Central Asia and Tibet the second-first Millennia B.C.

In: K. P. Paddaya et. al., eds. Recent research trends in South Asian archaeology. Proceeding of the Professor H. D. Sankalia Birth Centenary Seminar, Pune, Deccan College and Post Graduate Research Institute. pp. 205-16.

Oakley, E. S. 1905. Holy Himalaya. London: Oliphant Anderson and Ferrier.

Oakley E. S. & T. D. Gairola. 1935. Himalayan Folklore. Allahabad:

Government Press.

Pande, B. D. 1937. Kumaun ka itihas. Almora: Shakti Press.

Pande, G. D. ed. 1989. Manaskhand. Varanasi: Sri Nityanand Smarak Samiti.

81

Pande, Vasudha. 2018a. Anthropogenic landscapes of the Central Himalayas. In: Cederlof G. & Mahesh Rangarajan, eds. At nature’s edge. Delhi: Oxford University Press, pp. 19-60.

_____. 2018b. The making of a 'Kumauni' artifact: the epic Malushahi.

Himalaya, 38 (1), pp. 145-58.

_____. 2017. Borderlands, empires and nations, Himalayan and Trans- Himalayan borderlands (c 1815–1930). Economic and Political Weekly, LII (15), pp. 68-78.

_____. 2015. Making Kumaun modern: family and custom c 1815–

1930. Delhi: Nehru Memorial Museum & Library.

_____. 2013. Stratification in Kumaun c. 1815–1930. Delhi: Nehru Memorial Museum & Library.

Pandey, Trilochan. 1977. Kumauni bhasha aur uska sahitya. Lucknow:

Hindi Sansthan.

William, R. Pinch. 2006. Warrior ascetics and Indian Empire.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pinkney, Andrea M. 2013. An ever-present history in the land of the Gods: modern Mahatmya writing. Uttarakhand International Journal of Hindu Studies, 17 (3), pp. 229-60.

Pranavananda, Swami. 1950. Explorations in Tibet. University of Calcutta Introduction by Syama Prasad Mookerjee and Foreword by S. P. Chatterjee, Head Department of Geography (first edition August 1939).

Pranavananda, Swami. F. R. G. S. 1949. History of Kailas Manasarovar with maps with a Forword by Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru, dedi- cated to His Holiness Sri 1108 Narayan Swami ji Maharaj, Sri Narayan Swami Ashram, Soosa. Calcutta: S.P. League.

Rhoades, R. E. & S. I. Thompson. 1975. Adaptive strategies in Alpine environments: beyond ecological particularism. American Ethnologist, 2 (3), pp. 535-51.

Sankrityayana, Rahul. Himalaya Parichaya, I. Allahabad: Law Journal Press.

Sankrityayana, Rahul. (Vikram Samvat 2015). Kumaun. Varanasi:

Gyanmandal.

Sanwal, R. D. 1966. Bride-wealth and marriage stability among the Khasi of Kumaon. Man, New Series, 1 (1), pp. 46-59.

82

Sax, William. 1991. The mountain Goddess. New York: Oxford University Press.

_____. 1990. Village daughter, village Goddess: residence, gender, and politics in a Himalayan pilgrimage. American Ethnologist, 17 (3), pp. 491-512.

Schaik, Sam van. 2011. Tibet: a history. Yale: Yale University Press.

Shailesh, Hari Dutt Bhatt. 1976. Garhwali bhasha aur uska sahitya.

Lucknow: Hindi Samiti.

Sharma, D. D. 2009. Cultural history of Uttarakhand. Delhi: IGNCA.

Sherring, C. A., 1906. Western Tibet and the British borderland: the sacred country of Hindus and Buddhists. London: Edward Arnold.

Smith W. L. 2001. Stri Rajya: Indian accounts of the kingdom of women. In: Klaus Kartunnen & Petterei Koskikallio, eds.

Vidyairnavavandanam, essays in honour of Asko Parpola.

Helsinki: Finnish Oriental Society, pp. 465-77.

Thapar, R. 1979. Ancient Indian social history: some interpretations.

New Delhi: Orient Longman.

Tolia, R. S. 1996. British Kumaun–Garhwal: an administrative history of a non-regulation province, vol. 2. Almora: Almora Book Depot.

_____. 1994. British Kumaun Garhwal. Almora: Almora Book Depot.

Tucci, G. 1956. Preliminary report on two scientific expeditions in Nepal. Roma: ISMEO.

Upadhyaya, U. D. 1979. Kumaun ki Lok gathaon ka sahityik aur sanskritik adhyayan. Bareilly: Prakash Book Depot.

Whitmore, Luke. 2018. Mountain, water, rock, God: Kedarnath in the Twenty First Century. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Xuan, Zang (Hiuen Tsiang). 1906. Buddhist records of the Western World, vol. I. trans. by Samuel Beal. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner.