Family Effects on Family Formation

Volltext

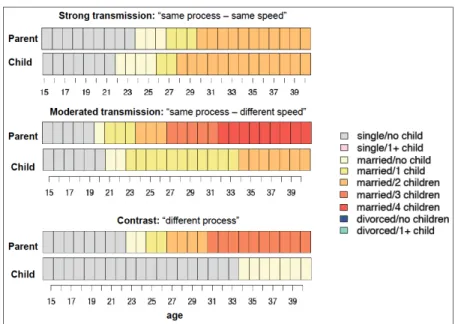

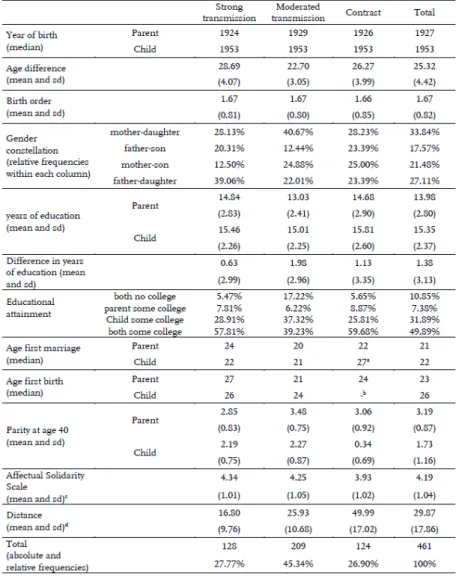

Abbildung

ÄHNLICHE DOKUMENTE

Percentage explained is even slightly negative for the endowment effect of family formation, ranking it among the least important factors, as in Bobbitt- Zeher’s analysis..

For each treatment (namely, whether experiencing at least one, exactly one, exactly two, at least three, housing, economic, physical, mental, death and disharmony,

The study fills an important gap in research, that is establishing how entrepreneurial family firms and non-family firms initiate innovation and whether innovation practices

The wife, children, brothers, sisters, other relatives, friends, and colleagues follow the funerary cortege at the tomb owner’s burial, as is depicted in New Kingdom tombs..

«Arsenicum» überlegen!) Doch wenn man nicht als verderbt gelten, aber doch die Infos lesen wollte, durfte man die Sei- ten nicht aufschneiden, sondern musste sie sanft biegen und

The comparative analysis of the members of this family shows the relevance of social inequalities in different context and their strategies to use a transnational orientation

Referring to the aims of family policy, I would like to repeat my notion that, in this dimension, one finds a rather strong continuity in Soviet policies since 1936, as well as

Hannes’ favourite subjects are Maths and English?. Hannes is younger than