Research Collection

Journal Article

Institutional complexity, management practices, and firm productivity

Author(s):

Karplus, Valerie J.; Geissmann, Thomas; Zhang, Da Publication Date:

2021-06

Permanent Link:

https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000475533

Originally published in:

World Development 142, http://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105386

Rights / License:

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International

This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use.

ETH Library

Institutional complexity, management practices, and firm productivity

Valerie J. Karplusa,⇑, Thomas Geissmannb, Da Zhangc

aDepartment of Engineering and Public Policy, Carnegie Mellon University, Scott Hall, 5113, 5000 Forbes Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, United States

bDepartment of Management, Technology, and Economics, ETH Zürich, Switzerland

cInstitute of Energy, Environment and Economy, Tsinghua University, China

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Accepted 22 December 2020

Keywords:

Management Ownership China Productivity

Institutional complexity

a b s t r a c t

Formal structure is often considered important for the growth and survival of firms. Within the literature focused on the institutional antecedents of formalization, less attention has been paid to the drivers of formal management practices. To help fill this gap, we study how state and market institutional logics affect the adoption and utility of formal management practices in manufacturing firms. We theorize how institutional complexity, resulting from coexistent, conflicting state and market institutional logics, may exert differential pressure on state-owned and private firms’ decisions to adopt these practices, diverging from prior studies that focus primarily on the role of market logics in their adoption. We then test these propositions in a representative sample of 390 manufacturing firms in China with uniquely detailed data on structured management practices using regression analysis. Variation in ownership dif- ferentiates the relative influence of state and market institutional logics on firms in China’s transition economy. We find that measures of structured management practices are higher for state-owned firms, while scores are significantly lower for domestic private firms. We further show that, on average, a firm’s overall management practice score is positively and significantly related to total factor productivity (TFP) in state-owned firms, but the correlation is no different from zero in both domestic and foreign private firms. Our findings support a role for structured management practices as a response to institutional complexity, by enabling firms to satisfy multiple imperatives from distinct audiences.

Ó2021 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Across the world, firms vary widely in their adoption of structured management practices. Defined as explicit and measur- able incentives, disciplines, and routines that guide employees’

daily work, structured practices have been linked to better economic outcomes (Ichniowski, Shaw, & Prennushi, 1997;

Bloom & Van Reenen, 2007), treatment of labor (Distelhorst, Hainmueller, & Locke, 2017), and environmental stewardship (Bloom, Genakos, Martin, & Sadun, 2010; Boyd & Curtis, 2014).

Efforts to advance the theory and practice of management through surveys, experiments, and training programs have proliferated over the past several decades. Yet, we lack a thorough understanding of what explains the extent of management practice formalization and its relationship to performance.

Contingency theory recognizes that the emergence of formal structure in firms depends on internal and external influences.

Prior work has examined the role of environmental turbulence

(Burns & Stalker, 1961; Sine, Mitsuhashi, & Kirsch, 2006), trust in state institutions and legitimation processes (Assenova &

Sorenson, 2017; Goedhuys & Sleuwaegen, 2013), and pressure from external audiences (Delmas & Toffel, 2004; Westphal, Gulati, & Shortell, 1997; Bromley, Hwang, & Powell, 2012; Zott &

Huy, 2007) as determinants of decision to formalize. Among these studies, limited attention has been focused on structured manage- ment practices, which are defined here as explicit and regularized disciplines followed widely by an organization’s members that guide day-to-day operations. These practices are rarely measured systematically and definitions vary across studies.

Here, we overcome these limitations to shed new light on how institutional processes relate to the adoption and impact of a set of structured management practices in manufacturing firms. Our interest is in understanding whether these practices, which are often associated with a logic of market efficiency and performance, may also be shaped by the administrative logic of the state. We examine this question in a unique setting, mainland China, where overlapping state and market logics bear simultaneously on state- owned firms, while private firms are disproportionately subject to a market logic. We hypothesize that this particular instance of ‘‘in- stitutional complexity” (Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta, &

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105386

0305-750X/Ó2021 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd.

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

⇑Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: vkarplus@andrew.cmu.edu (V.J. Karplus), zhangda@mail.

tsinghua.edu.cn(D. Zhang).

Contents lists available atScienceDirect

World Development

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / w o r l d d e v

Lounsbury, 2011) exerts distinct effects on structured management practices in each firm type and could operate through either active or passive channels of institutional influence, following Oliver (1991). In developing theory and empirical evidence, we further extend the institutional complexity literature to a non-Western context.

To examine these relationships, we leverage a recent body of work, known as the empirical management literature in eco- nomics, which supplies novel measures of the nature and extent of firms’ structured management practices (Bloom & Van Reenen, 2007; Bloom, Genakos, Sadun, & Van Reenen, 2012). Based on interviews with firm managers, this literature quantifies struc- tured management practices introduced in firms. Questions are designed to measure the extent to which a firm has adopted a set of formal practices related to operations, targeting, monitoring, and incentives. These practices are not intended to be an exhaus- tive descriptor of a firm’s managerial quality. We use these mea- sures to examine empirically the relationship between institutional forces and structured management practices.

Our primary contribution is to show that in manufacturing firms, structured management practices and their relationship to productivity become stronger as firms grow more complex in their institutional influences. Surprisingly, we find that these practices are least prevalent among domestic private firms, and that the cor- relation between overall management scores and performance outcomes is no different from zero in both domestic and foreign private firms operating in China. Our findings are consistent with the notion that structured management practices emerge in condi- tions of institutional complexity (Greenwood et al., 2011) and may function as a means of reconciling disparate influences. Our study illuminates an additional dimension that plausibly affects the extent and value of (management practice) formalization: the combination of institutional logics that a firm confronts in its inter- actions with external audiences. If adopting certain practices can help to satisfy competing institutional imperatives, they may be more prevalent in organizations that face such complexity relative to those that face fewer imperatives.

The remainder of this manuscript is structured as follows.

Building on prior work that examines institutional antecedents of firm formalization, we theorize in Section2how coexistent state and market logics, by exerting different influences on state- owned and private firms, may shape the adoption and impact of structured management practices. We then discuss how we test these propositions empirically in Section3and describe the results and their relationship to our hypotheses in Section4. The implica- tions of our findings for theory and future research are summa- rized in Section5.

2. Theory

2.1. Why do firms formalize?

Scholars have long been interested in the drivers and utility of formal structure in organizations. While formalization has been cast as a defining feature of the modern organization (Pugh et al., 1963), instances of formalization vary across studies. Examples considered in prior work include registration (Assenova &

Sorenson, 2017), quality certification (e.g., of compliance with standards) (Goedhuys & Sleuwaegen, 2013), mechanistic versus organic management systems (Burns & Stalker, 1961), policies and practices for evaluating performance (Bromley et al., 2012;

Westphal et al., 1997; Zott & Huy, 2007), and role formalization, specialization, and administrative intensity in founding teams (Sine et al., 2006). While precise mechanisms that mediate differ- ent instances of formalization vary across studies, external pres-

sures, imperatives, and rewards are found to be important driving influences. In many cases, adopting formal structure is associated with superior performance outcomes (Assenova &

Sorenson, 2017; Goedhuys & Sleuwaegen, 2013; Sine et al., 2006), although several studies have observed a disconnect between adoption and implementation (‘‘decoupling”) as man- agers respond to external pressures by adopting (or claiming to adopt) formal practices without implementing them in core activ- ities (Bromley et al., 2012).Westphal et al. (1997)find early adop- ters of Total Quality Management (TQM) customize practices to reap efficiency gains, while late adopters gain legitimacy benefits from adopting its normative template.

Within the subset of the formalization literature focused on structured management practices, one strand explains adoption decisions as a rational strategy for enhancing productivity. Accord- ing to this view, the impetus to formalize management practices largely originates within the firm: the strength of managers’ incen- tives, which increase with exposure to market competition and managerial autonomy, drive them to adopt practices to enhance productivity. Multiple studies find a systematic empirical relation- ship between management practices and productivity in firms (Bloom & Van Reenen, 2007), including in firms in developing countries (McKenzie & Woodruff, 2017; Bloom, Eifert, Mahajan, McKenzie, & Roberts, 2013; Bruhn, Karlan, & Schoar, 2018).

Bloom, Sadun, and Reenen (2016)assert that the empirical rela- tionship can be generalized to interpret management practices as a ‘‘technology,” although specific practice choices may be condi- tioned by firm circumstances. Rational explanations for manage- ment practice adoption are not limited to firms, however. Within state hierarchies, structured management practices have long been recognized to contribute to precision, speed, accumulation of expertise, and continuity of activities (Weber, 1947). Hospitals and schools have similarly been found to benefit from structured management in achieving their objectives, which may not include, or may extend beyond, efficiency and profit (Bloom, Propper, Seiler, & Van Reenen, 2013; Bloom, Lemos, Sadun, & Van Reenen, 2015).

A second explanation for the formalization of practices focuses on the role of environmental turbulence.Burns and Stalker (1961) posit that organic management structures are more advantageous when the environment is changing rapidly, while more mechanis- tic structures suit firms operating in stable conditions. Revisiting this view, Sine et al. (2006) finds that formalization can be an advantage in turbulent environments, especially for venture- backed, young firms, which differ from the established firms in the setting ofBurns and Stalker (1961).Sine et al. (2006)suggest that while ‘‘mature organizations with well-defined structure and embedded practices typically need to become more organic and flexible in order to adapt to dynamic environments [...], new ven- tures are already extremely flexible and attuned to their environ- ment, but often lack the benefits of organizational structure, such as low role ambiguity, high levels of individual focus and discre- tion, low coordination costs, and generally high levels of organiza- tional efficiency.” However, this literature has so far not considered the possibility that environmental turbulence might engender dif- ferent responses in firms facing distinct institutional imperatives.

A third set of explanations focuses on institutional pressures as drivers of management practice adoption (Fiss & Zajac, 2004; Zott

& Huy, 2007; Bromley et al., 2012; Delmas & Toffel, 2004). Within this literature, there is an emphasis on the external origins of adop- tion processes. These influences can be passive, for instance, if practices reflect a firm’s historical ties, or active, if adoption consti- tutes a strategic response (Oliver, 1991). In Delmas and Toffel (2004), firms adopted environmental management practices in response to stakeholder pressure. Adoption is found to occur in some instances without implementation (Zott & Huy, 2007), with

this decoupling constituting a rational response to external pressures when they ‘‘conflict with core aspects of production”

(Bromley et al., 2012). A similar pattern was found in Westphal et al. (1997), as latecomers adopted the normative variant of prac- tices legitimated by successful early adopters. However, the authors suggest ‘‘that policy-practice decoupling may decline over time because: (a) more emphasis is placed on implementing policies, (b) policies are selected in part because they can be imple- mented and measured, and (c) pressures in the environment that drive the creation of policies may independently be changing prac- tices and outcomes, regardless of policy” (Bromley et al., 2012).Fiss and Zajac (2004)find that German firms engage in decoupling by declaring a shareholder value orientation but failing to implement it, although decoupling is reduced when influential and committed key actors support implementation. A two-year study of entrepre- neurial British firms showed that ‘‘symbolic actions” enabled entrepreneurs to acquire resources for new ventures (Zott & Huy, 2007). Thus, practice formalization may take place for symbolic or instrumental reasons, or the former justification may morph to the latter over time.

2.2. Institutional logics and firm formalization

Within the formalization literature, attention has begun to crys- tallize around how institutional logics influence organizational decisions to formalize. Institutional logics are sets of principles that guide ‘‘how to interpret organizational reality, what consti- tutes appropriate behavior, and how to succeed” (Thornton, 2004). These logics are proposed to play a role in firms’ formaliza- tion of management practices, as logics may sanction the ratio- nales discussed above. For example, in Bromley et al. (2012), non-profits adopted for-profit like management structures when the dominant institutional logic evolved to reward it. In Westphal et al. (1997), early TQM adopters realized productivity gains, while late adopters reaped mainly legitimacy benefits, sug- gesting different institutional logics at work among each group.

We propose that structured management practices are more likely to be adopted, and to be associated with productivity gains, when they satisfy multiple competing institutional logics. We fol- low the institutional logics perspective and define ‘‘institutional complexity” as occurring when an organization faces coexistent, conflicting logics (Thornton, Ocasio, & Lounsbury, 2012;

Greenwood et al., 2011). Demands from competing logics may mit- igate the type of uncertainty described inGoodrick and Salancik (1996), limiting discretion at the organizational level. Uncertainty about the institutional prescription was associated with higher rates of (more expensive) cesarean delivery in private compared to public hospitals (Goodrick & Salancik, 1996). Specifically, they write: ‘‘Organizations thus generate variation in practice while conforming to their institutions by pursuing their strategic inter- ests within the limits of the discretion permitted by the institu- tions generating it” (Goodrick & Salancik, 1996). To the extent that (multiple) institutional pressures favor formalization, firms may be more limited in their discretion to pursue their strategic interests. While prior studies have focused on how institutional logics affect firm decisions, we are unaware of any studies that have focused specifically on how institutional complexity may affect decisions to formalize.

Institutional complexity requires firms to reconcile competing logics in their day-to-day operations. Among the range of paths a firm facing institutional complexity could pursue, structured man- agement practices are plausibly ambidextrous and therefore advantageous: a manager could instruct employees to go through the motions in order to convey professionalism to external audi- ences, while at the same time increasing employee familiarity with management practices could lay a foundation for future imple-

mentation and associated efficiency gains. As discussed in Bromley et al. (2012), decoupling may decline over time. Firms not subject to competing imperatives may have less reason to adopt an ambidextrous solution, especially if this reduced complexity confers a performance advantage. The proposition that formalization of management practices increases with institutional complexity is the core idea that we test in our empirical analysis.

2.3. State and market logics in China’s transition economy

Examining whether institutional complexity affects the formalization of management practices requires a setting in which the influence of prevailing institutional logics varies across organi- zations. For this, China is an ideal setting: starting with the coun- try’s reform and opening period in 1978, a market logic was increasingly coexistent alongside a logic of state planning, a trend that continued into the first decade of the 2000s with China’s 2001 entry into the World Trade Organization. This coexistence of state and market logics in China has been characterized as ‘‘capitalism with Chinese characteristics” (Huang, 2008).

To theoretically ground our focus on state and market logics in the Chinese context, we draw on the typology of interinstitutional systems provided inThornton et al. (2012)(see Table 3.1). We start with ideal types that distinguish state and market logics and could influence a firm’s formal managerial practices: sources of legiti- macy (democratic participation versus share price), sources of authority (bureaucratic domination versus shareholder activism), sources of identity (social and economic class versus faceless), basis of norms (citizen membership versus self-interest), basis of attention (status of interest group versus status in market), basis of strategy (increase community good versus increase profit), and economic system (welfare versus market capitalism). While most of these distinctions apply in the Chinese context, bureaucratic domination is a more prominent feature of the state logic than democratic participation, with legitimacy resting on the functional competence of the state in delivering on the economic growth, welfare, and social advancement demands of the Chinese popula- tion (Shirk, 2007). The market logic in China largely mirrors its counterparts in the West, and is still widely viewed as a foreign transplant (Huang, 2008), at odds with the state and society’s emphasis on collective welfare.

Historical context illustrates why state and market logics in China coexist in tension, leading to the form of institutional com- plexity we study here. The decades prior to reform and opening were characterized by near total state ownership and control of the major industries. The market logic took root in China under Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s and evolved under Jiang Zemin in the 1990s. Private business went from being outlawed and limited to fewer than eight employees, to Jiang declaring that entrepre- neurs should be recognized as an ‘‘Advanced Productive Force”

(Guo, Jiang, Kim, & Xu, 2014). By the period of our study, most of China’s economic growth was driven by private firms (Huang, 2008). Nevertheless, state-owned firms remained stalwarts of Chi- na’s economic landscape in almost every sector. State-owned firms report to different levels of the governing hierarchy in China.

Shortly before our study period, large firms in strategic industries were placed under central government control, while firms con- trolled by provincial and lower governments faced pressure to grow more market oriented, without compromising their account- ability to the state. As a result, state-owned firms remain bound by sources of legitimacy, authority, and identity and norms deriving from the state logic, but must simultaneously succeed in a system that increasingly values share price, market status, and profit, lead- ing to institutional complexity as defined by the institutional logics perspective (Thornton et al., 2012). Domestic private firms enjoy fewer class and citizen membership privileges or welfare protec-

tions, but also possess greater flexibility to focus on market ends through whatever means are most expedient.

In the majority of settings studied, market logics are assumed to be important, or even dominant, given the capitalist structure of the economy. Nevertheless, even in these settings, firms face state imperatives, in the form of regulation (environmental, health, and safety), reporting requirements, or directives to support policies or priorities. Tensions between state and market logics may be more pronounced in organizations providing public goods, such as schools or hospitals. A market logic would prioritize revenue growth and eventually productivity and profit, while a state (or administrative) logic would prioritize a more diverse set of objec- tives that follow state priorities. In capitalist economic systems, where a majority of firms are private, at least in most sectors, we would observe the combined effect of these institutional logics, but cannot necessarily distinguish between them because of the relatively uniform influence of prevailing institutional logics within firm populations.

2.4. Hypotheses

We argue that China’s particular form of institutional complex- ity exerts its strongest influence on structured management prac- tices in state-owned firms through three channels: (1) conformity to the imperatives of the central planning process and state objec- tives, (2) the growing tendency of policymakers to benchmark them against foreign multinationals, and (3) rising competition as state-owned firms, which are less productive on average, con- front market logics through the reform and opening process. Thus, state-owned firms may adopt management practices to synchro- nize their activities with state objectives and planning processes, strengthen symbolic legitimacy by looking similar to Western counterparts, and achieve productive efficiencies that strengthen competitiveness. In the case of private firms, channels (1) and (2) are not (or are at least less) relevant because private firms are autonomous from the state. Channel (3) is less relevant because private firms already possess a productivity advantage over state-owned firms, although private firms also faced competition and sharper profit motives.

Organizations operating in the same field may experience insti- tutional complexity to different degrees (Greenwood et al., 2011).

In our setting, the overlap in state and market logics was more pro- nounced for state-owned firms than for private firms operating in the country’s manufacturing sector during the first decade of the 2000s. The modernization of state-owned firms in China was a government priority in the late 1990s and early 2000s, increasing pressure upon them to compete with their global multinational counterparts. Evidence that productivity lagged private firms led firms and their state patrons to invest in upgrading managerial quality. State-owned firms were encouraged to become world class companies and contracted with global consulting firms to receive training in international best practice (Steinfeld, 2010). The wide- spread proliferation of fake ISO9001 certificates in China suggests that management quality has symbolic value (Heras-Saizarbitoria

& Boiral, 2019). To the extent that state-owned firms benefit from external perceptions of their management quality, these firms will have stronger incentives to develop formal management practices, especially those observable to outside parties.

We focus first on management practice levels. Our null hypoth- esis is that domestic private firms will have an equal or higher propensity to adopt management practices, because their man- agers are more strongly incentivized to increase profit, following a market logic. If management practices are solely a strategy for enhancing productivity, a firm with managers better positioned to reap the rewards of productivity gains would be more likely to adopt these practices. This reasoning is supported by evidence

from the former Soviet countries, where private firms score higher on management practice measures than do state-owned firms (Bloom, Schweiger, & Van Reenen, 2012). However, China’s institu- tional setting is different: state logics retain primacy in China, whereas in post-Soviet Russia and Eastern Europe, privatization occurred rapidly and state logics were dismantled or discredited, reducing institutional complexity. A state logic emphasizes eco- nomic planning functions, such as target setting and monitoring, that extend into firms, alongside imperatives to raise economic competitiveness. Therefore, if this confluence of institutional logics is playing a dominating role, we expect that:

Hypothesis #1:Structured management practice scores will be higher on average for state-owned firms compared to domestic private firms.

To test our conjecture that institutional complexity may drive formalization of management practices, we examine effects sepa- rately in two subsets of our state-owned firm sample that were more or less exposed to pressure from the state institutional logic.

Among state-owned firms, those directly controlled by the central government were targeted for consolidation and modernization in order to elevate their profile to those of major international com- petitors (Hsieh & Song, 2015; Li, Meng, Wang, & Zhou, 2008). In con- trast, state-owned firms that report to local governments faced similar pressures to some extent, but the reform process required these firms, many of which were unprofitable at the outset, to rely more on the market, e.g. through corporatization (Lin, Lu, Zhang, &

Zheng, 2020). Thus, central state-owned firms faced greater institu- tional complexity, in the sense that they faced pressure from both state and market logics, while local state-owned firms were exposed more directly to the market logic. Our null hypothesis is that central state-owned firms will have equal or lower management practice scores relative to local state-owned firms, consistent with a domi- nant influence of the market logic for the latter. We hypothesize:

Hypothesis #2:Structured management practice scores will be higher on average for central state-owned firms compared to local state-owned firms.

Does institutional complexity affect which firms obtain productivity benefits from adopting management practices?

Above, we discuss how state-owned firms may have felt substan- tial pressure to adopt management practices for both symbolic and instrumental reasons, to satisfy coexistent institutional logics.

Private firms, by contrast, faced more uncertainty—and less pres- sure—from external institutional audiences. Thus, the managers of these firms may have more readily pursued alternative strate- gies to achieve their objectives. We contrast this reasoning with our null hypothesis, which is that the management-productivity relationship should be strongest in the firms most exposed to a market logic, e.g. private firms. We hypothesize:

Hypothesis #3:State-owned firms will exhibit a stronger corre- lation between management practice level and productivity, com- pared to domestic private firms.

We return to our subcategories of state-owned firms to evaluate whether the relative influence of the state logic also plays a role in the extent to which firms benefit from management practice adop- tion. As discussed, central state-owned firms represented China’s commanding heights, and thus may have faced greater pressure to adopt structured management practices to compete successfully with the world’s largest modern corporations. Local state-owned firms, by contrast, would be expected to face less institutional complexity, and accordingly, greater discretion. Here, our null hypothesis is that local state-owned firms would benefit more from management practices, if these practices solely reflect a response to the market logic. This leads us to a final hypothesis:

Hypothesis #4:Central state-owned firms will exhibit a stronger correlation between management practice level and productivity compared to local state-owned firms.

In the following sections, we describe our tests of each hypoth- esis using firm-level data on management practices for a represen- tative sample of firms in mainland China.

3. Data and empirical approach

3.1. Measures of structured management practices

To observe structured management practices, we use individual and composite survey-based measures from the World Manage- ment Survey (WMS) (Bloom et al., 2012; Bloom & Van Reenen, 2007), which by 2014 covered 11,300 manufacturing firms in 34 countries. We use the 2004–2010 survey wave, which includes 542 Chinese manufacturing firms sampled to be representative of the full population (Bloom et al., 2012). The WMS groups practices into four functional categories: Operations (3 questions), Monitor- ing (5 questions), Targets (5 questions), and People (e.g, perfor- mance incentives) (5 questions) (for a copy of the full questionnaire, seeBloom & Van Reenen (2007)). Individual ques- tion scores are averaged by category, and all four category scores are equally weighted to obtain a composite overall management score. For the regression analysis, we convert all individual ques- tion scores to z-scores (number of standard deviations above or below the sample mean) to generate a normalized measure for each firm within the China sample.

Of the 542 firms in the WMS, 80 percent or 434 firms were suc- cessfully matched with data from the China Annual Industrial Sur- vey (CAIS). A management score is available for one year per firm and is observed once during the years 2006 to 2008 (15 firms were surveyed in 2006, 298 in 2007, and 77 in 2008), while many of the CAIS variables are observed annually. We take each firm’s manage- ment score as an indication of structured practices in place over the 2003–2008 period and focus on cross-sectional variation in management level and productivity estimates across ownership categories. Identified data from the WMS were used with permission.

We interpret the WMS scores as a measure of the extent to which structured management practices are widely adopted in the firm. Multiple steps were taken to ensure scores are reliable.

Survey question are open ended and designed to assess familiarity and extent of practice adoption. Interviewers trained in the WMS approach and interview techniques, and not interviewees, assigned scores, with the aim of reducing subjectivity. After each interview, the interviewer evaluated the reliability of the interview, and these

scores were included as controls in our regressions. To assess inter- nal validity, a subset of firms were re-surveyed, with scores based on responses of a different manager at a second plant belonging to the same firm, and correlations with the original scores were high (Bloom & Van Reenen, 2007; Bloom et al., 2016). The direction of correlations was further found to be consistent across alternative performance measures, including productivity, profitability, Tobin’s Q, sales growth rates, and firm survival rates, and to hold across culturally-diverse contexts (Bloom & Van Reenen, 2007).

3.2. China Annual Industrial Survey

Management scores were merged with firm economic data for 2003 to 2008 from the China Annual Industrial Survey (CAIS) (National Bureau of Statistics, 2010), which is conducted by the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics and is comprised of a repre- sentative sample of firms from the comprehensive Chinese Indus- trial Census, which is conducted every four years (National Bureau of Statistics, 2004, 2008). The CAIS contains information reported annually from a firm’s balance sheet, income statement, and other (mainly economic) characteristics for all firms registered in China with a sales value higher than five million CNY as well as all state-owned firms. Variables are transformed to real values using the input and output price deflators described in Brandt, Van Biesebroeck, and Zhang (2014), which are used with permission.

We use the standard ownership classification adopted by the Chi- nese National Bureau of Statistics, which is based on control rights and distinguishes among state-owned firms (defined as having a state majority or minority controlling shareholder), domestic pri- vate firms (majority domestic private ownership and a few remain- ing collective firms), foreign firms (majority non-Chinese ownership in paid-in capital), and Hong Kong/Macao/Taiwan firms (HMKT, similarly based on majority ownership).

After matching and cleaning, our resulting final sample includes 390 firms. Panel construction and data cleaning are described in detail inAppendix Section A1. The pre-cleaned and final samples do not differ significantly in terms of the distribution of manage- ment quality and other important covariates (see Appendix Table A3comparing matched and unmatched firms andAppendix Table A4comparing excluded and non-excluded firms). Descriptive statistics of key variables for the 390 firms in the final sample are given inTable 1. Firms range widely in age, with the 5th to 95th percentile spanning 2 to 47 years. On average, firms have a general management score of 2.64, very close to the average of the full

Table 1

Descriptive statistics of firm attributes from the Chinese Annual Industrial Survey and scores from the World Management Survey.

Mean Stdev 5% pc. 95% pc.

Output (value added)Y[mCNY] 149.7 613.8 4.3 528.0

LaborL[number of employees] 868.5 964.5 166 2611

Real capital stockK[mCNY] 477.4 2230.1 13.30 1593.6

Intermediate inputsS[mCNY] 346.6 898.2 10.09 1286.2

Mean-differenced compensationW[kCNY] 1.00 0.68 0.34 2.22

Firm age [years] 13.24 13.70 2 47

Overall management score 2.640 0.459 1.889 3.389

People score 2.651 0.455 1.833 3.333

Target score 2.543 0.570 1.600 3.400

Operations score 2.433 0.945 1.000 4.000

Monitor score 2.803 0.505 2.000 3.800

Share of ownership categories:

The share of domestic private firms is 44%, while 21% are state firms, 19% are foreign owned, and 16% are from Hong-Kong/Macao/Taiwan.

Distribution of firm size (number of employees):

(6250 employees): 11% of observations; (250<employees6500): 32% of observations;

(500<employees61000): 33% of observations; (1000<employees): 24% of observations

Notes: This table presents descriptive statistics of main covariates used in the analysis.mrepresents ‘‘million” andk‘‘thousand.” The statistics are based on the 390 firms successfully matched from the WMS sample and all years of observations.

WMS China sample, 2.71 (Bloom et al., 2012). The overall average score for Chinese firms is comparable to Brazil and significantly lower than firms in the U.S., which have an average score of 3.35, and Western European firms, which score on average above 3 (Bloom et al., 2012). We find that within ownership categories, industries account for similar shares of the total, with the excep- tion of the highly export-oriented textile industry, which has a lar- ger share of private firms (see Appendix Table A5). Correlations among key variables in the combined data set are shown inAppen- dix Table A6. We are unaware of similarly comprehensive data sets for other large developing countries such as Brazil or India. The quality of data required to compute firm productivity in develop- ing countries is notoriously poor, with ownership, employment, or wage variables missing for a high share of firm entries.

3.3. Ownership and management practices

To examine whether management level varies by ownership type (Hypothesis #1 and #2), we first compare raw overall man- agement scores and sub-scores using simple t-tests. Direct com- parisons of average scores by ownership category might fail to control for important firm-specific characteristics that are associ- ated with both ownership and management. Pooled regressions are therefore run to test Hypothesis #2 using the following specification:

Mi¼a0þb|wWiþb|xxitþit; ð1Þ where the main variable of interest, firm ownership, isWi, a vector containing both Central State and Local State ownership (other ownership types are pooled in the comparison group). Variables inxit include firm-, sector-, and location-specific variables defined at the firm level. Firm-level variables include firm size (natural log- arithm of main business revenue), a firm’s capital cost by year, and its share of foreign ownership (if any). Regressions also include three location-specific variables, per-capita GDP, annual GDP growth rate (in percent), and the ratio of foreign direct investment (FDI) to GDP in the city where the firm is located. Per-capita GDP captures the development level of the city, and the GDP growth rate is a rough proxy for a city’s political priorities and economic trajec- tory. We include a city’s FDI share to account for the possibility that firms may learn management practices from foreign market entrants in close proximity, as discussed inGörg and Greenaway (2004). Finally, we include both capital cost and state share at the sector level, in addition to industry fixed effects.

3.4. Estimating the management-productivity relationship

To evaluate the relationship between management and produc- tivity (Hypothesis #3), we introduce the management score (either the composite general management score or subscores) as a covariate in the firm’s production function, followingBloom et al.

(2016). Production functions are widely used in economics to describe a firm’s output as a function of inputs, including labor, capital, and materials. Productivity is the residual output not explained by the inputs; thus the coefficient on management score reveals how much of this residual variation the score explains.

Running the regressions conditional on ownership allows for ownership-specific input choices and a full interaction with a range of firm characteristics. We specify a parametric Cobb- Douglas value-added production function with yit equal to value added (output net of materials costs) of firmiin yeart, with lower case letters indicating variables in log form, as

yit¼a0þbkkitþbllitþbMMiþb|xxitþit: ð2Þ Inputs are capitalKand laborL. Capital inputsKare based on the real capital stock, which we derive as described Appendix

Section A2. LaborLis the total number of workers employed by a firm in a given year. The time-invariant management quality z- scoreMis directly included in the production function, and its coef- ficient indicates how much of a firm’s residual productivity it explains. VectorXis comprised of year and two-digit industry fixed effects, firm age, and mean-differenced employee compensation, which controls for variation in labor skill. Employee compensation includes wages as well as welfare payments, and the mean is com- puted annually at the two-digit industry level. The underlying assumption is that the more skilled a firm’s work force is on aver- age, the higher the firm’s employee compensation per worker com- pared to the industry’s average in a specific year. All financial variables (e.g., value-added entries) are deflated to real values. Fur- thermore, to control for interview heterogeneity, six interviewer fixed effects are included, in addition to the assessed reliability of the interview (scale from 0 to 100 percent) and the duration of the interview (in minutes) in logs.

To test Hypothesis #4, we pool our sample and focus on the interaction between ownership and management for central and local state-owned firms. This empirical choice is supported by the broad similarity in coefficients on inputsKandLacross owner- ship types in the full interaction regressions. All firms are com- pared to a common reference group, non-domestic firms, which include Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan (HKMT) firms, domestic private firms, and foreign private firms. The pooled model with ownership interaction is specified as follows:

yit¼a0þbkkitþbllitþbMMiþbWWiþbMWMiWiþb|xxitþit: ð3Þ The coefficientbMW on the interaction of ownershipWiand man- agement scoreMi captures the ownership-specific management- productivity relationship. We use this model to compare the two categories of state-owned firms, central and local state firms, which is not possible in the full interaction (Table 4) due to the small size of the central state-owned firm sample.

4. Results

4.1. Structured management practices by ownership

To test our first two hypotheses, we begin by visually and sta- tistically comparing overall management practice scores across ownership types. Average management scores are computed by ownership and reported in Table 2. Comparing management scores, we find that on average state-owned firms are relatively well managed (2.67, panel (a)) compared to domestic private firms (2.52, panel (b)), consistent with a role for institutional complexity (Hypothesis #1). InTable 2, daggers and circles are used to indicate the statistical significance of average score differences between central state and domestic private firms and between local state and domestic private firms, respectively. The fact that domestic private firms fall below the overall China mean and median levels, while state-owned firms rank higher on average, contrasts sharply with evidence from post-Soviet countries reported inBloom et al.

(2012), which finds low management scores for state-owned firms, relative to privatized and private firms. State-owned firms are less well managed compared to foreign firms (2.85, panel (c)), and sta- tistically similar to Hong Kong/Macau/Taiwan firms (2.61, panel (d)) (all differences cited are statistically significant at the 10% level or higher).

We further distinguish between central and local state-owned firms (panels (e) and (f) inTable 2), and find that central state- owned firms score higher on overall management score as well as within all sub-categories except for ‘‘People” (superscripts indi- cate statistically-significant differences). The findings for overall

management score are consistent with Hypothesis #2. Remark- ably, the average overall management score for central state- owned firms is not statistically different from foreign firms. It is consistent with evidence that top-performing central state- owned firms are benchmarking themselves against leading global firms (Elliott & Zhou, 2013). However, local state firms are not management laggards. These firms are typically smaller than cen- tral state firms and tend to be more regionally-focused. As shown inTable 2, local state firms (panel (f)) compare favorably to domes- tic private firms (panel (b)) on Target, Operations, and Monitoring sub-scores, as well as on overall management score. These differ- ences are statistically significant. The distributions of management scores by ownership are shown inAppendix Fig. A4.

To evaluate the relationship between institutional complexity and structured management practices in a controlled setting, which provides a stronger test of Hypotheses #2, we estimate Eq.

(1). Results are displayed inTable 3. The partial effect of central state ownership on management score is strongly positive and sta- tistically significant, while the correlation between local state ownership and management score is not significant, e.g. no differ- ent from the comparison group of non-state firms, consistent with Hypothesis #2. Management z-score increases by an estimated 0.28 to 0.34 standard deviations from the mean if a firm is con- trolled by the central state, relative to local state-owned firms and the comparison group, with a statistical significance level of

one percent. The comparison group includes private, HKMT, and foreign firms.

The other regression coefficients are also informative. The coef- ficient on foreign ownership share is highly statistically significant, consistent with the comparison of the raw score averages above. In column (3), an increase in foreign ownership share by 10 percent- age points corresponds to an increase in the management z-score by 0.032 standard deviations from the mean. The correlation between firm size and management score is significant and posi- tive, but does not absorb the correlation with ownership. Coeffi- cients on capital cost, as well as nearly all of the sector- and location-specific variables, are not statistically significant. Only per-capita GDP is positively correlated with management score, perhaps because eastern coastal urban centers tend to be both wealthier and attract more foreign-direct investment, which might facilitate the diffusion of management practices. However, the inclusion of per-capita GDP does not change the magnitude and significance of the coefficient on central state ownership. A full cor- relation table is included asAppendix Table A6.

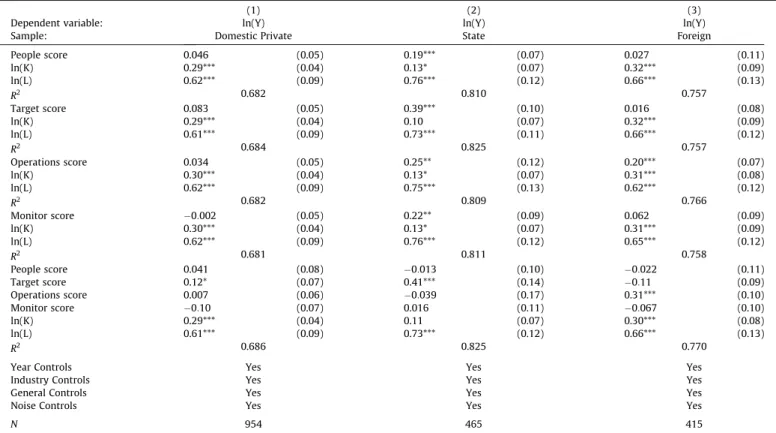

4.2. Ownership and the management-productivity relationship

To examine the relationship between management score and productivity, we begin in Table 4 by comparing the coefficients on management across ownership types by estimating the produc- Table 2

Management scores by ownership type (test of Hypotheses #1 and #2).

Mean Stdev Mean Stdev

(a) State[86] (b) Domestic PrivatePP [163]

Overall management score 2.666 0.402 2:519yy 0.453

People score 2.634 0.465 2.599 0.468

Target score 2.591 0.464 2:404yy 0.539

Operations score 2.610 0.784 2:138yyy 0.951

Monitor score 2.802 0.429 2:685yyy 0.503

Output (mCNY) 171.8 686.1 124:0yyy 295.3

Employees 949.7 1295.1 810:7yyy 981.2

Capital price (kCNY) 0.217 0.481 0:198y 0.126

Labor price (kCNY) 25.8 22.8 18:2yyy

Output per employee (kCNY) 618.0 1135.7 509.8 833.3

(c) Foreign[82] (d) HKMT[59]

Overall management score 2.852 0.451 2.608 0.466

People score 2.783 0.452 2.633 0.390

Target score 2.761 0.647 2.512 0.590

Operations score 2.866 0.835 2.339 1.027

Monitor score 3.022 0.491 2.781 0.547

Output (mCNY) 179:5þþþ 238.6 60.2 93.4

Employees 1310.5 2156.0 743.1 711.3

Capital price (kCNY) 0.200 0.152 0.344 1.190

Labor price (kCNY) 39.0 31.5 22.1 16.4

Output per employee (kCNY) 901.2 1548.7 360.7 476.6

(e) Central State[14] (f) Local State[72]

Overall management score 2.810* 0.444 2:638°° 0.391

People score 2.631 0.603 2.634 0.438

Target score 2.743* 0.517 2:561°° 0.451

Operations score 3.000** 0.809 2:535°°° 0.761

Monitor score 3.014** 0.511 2.761 0.402

Output (mCNY) 1177.2*** 3246.0 167.2 404.6

Employees 1669.7*** 1521.1 882.7 718.4

Capital price (kCNY) 0.153 0.051 0.185 0.181

Labor price (kCNY) 44.9** 38.4 27:3°°° 22.7

Output per employee (kCNY) 685.7 815.6 738:3° 1499.7

Notes: This table shows summary statistics for management practices by management quality category, overall and by ownership. Square brackets indicate the number of firms. Statistics are based only on the year that the WMS was conducted.mrepresents ‘‘million” andk‘‘thousand.” Foreign firms are defined as firms with a majority share of foreign ownership. Output is value added. Capital price is the sum of interest and depreciation expenses and opportunity cost of equity (assumed to be three percent) divided by the real capital stock. Labor price is wages and welfare expenses divided by the number of employees. Asterisks *** indicate significance at the 1 percent level, ** at the 5 percent level and * at the 10 percent level of the one-sided unpaired t-test of the comparison of the respective means of central and local state firms. Analogously, the following symbols represent significance levels of additional one-sided unpaired t-tests: pluses (+) for the comparison of central state$foreign, daggers (y) for the comparison central state$domestic private and circles () for the comparison local state$domestic private.