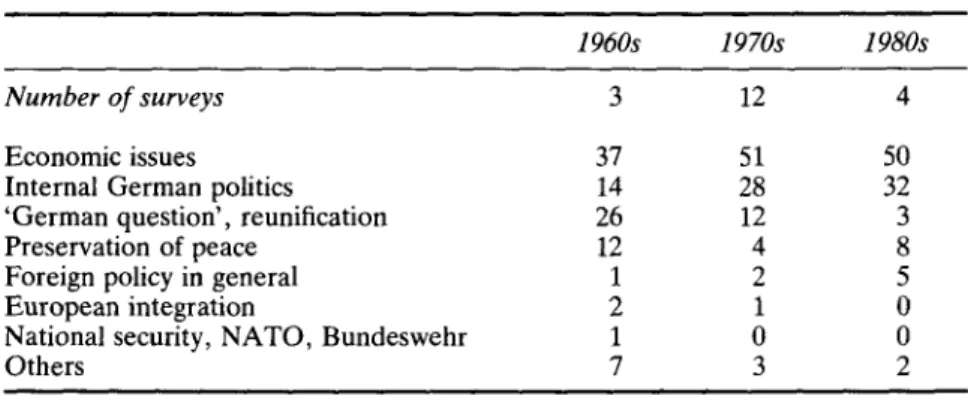

5 The Bundeswehr and Public Opinion

Volltext

Abbildung

ÄHNLICHE DOKUMENTE

describes spaces open to the general public, yet with a tem- porary accessibility defined through social interaction. They actually are private property: areas inside private houses

Average happiness appears not higher in the countries where hedonic values are most endorsed (r=+.O3). For instance, the three least happy nations are respectively low,

The low-skilled are often mentioned in European policy documents because low skills are associated with negative labour market outcomes (lower employment rates and salaries,

In order to better understand where the public stood regarding a detailed final status agreement, respondents were asked: “If the Israeli government approves a permanent

Peetre, Rectification ` a l’article “Une caract´ erisation abstraite des op´ erateurs diff´ erentiels” Math.. Friedrichs, On the differentiability of the solutions of linear

61 The proposal was rejected by most of ASEAN member states for three main reasons. First, the multilateral defense cooperation would send a wrong signal to major powers. It

63 Such educational measures to train the armed forces in civilian skills accelerated the military’s involvement in economic activities that required not only conversion

Depending on the cellular context and receptor species (apparent affinity of human EPO for huEPOR was about three times as high as that for rodent EPOR), EPO bound at 10 to 200