Research Collection

Other Journal Item

Processing of an ambiguous time phrase in posttraumatic stress disorder: Eye movements suggest a passive, oncoming perception of the future

Author(s):

Pfaltz, Monique C.; Plichta, Michael M.; Bockisch, Christopher J.; Jellestad, Lena; Schnyder, U.; Stocker, Kurt

Publication Date:

2021-05

Permanent Link:

https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000476656

Originally published in:

Psychiatry Research 299, http://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113845

Rights / License:

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International

This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use.

ETH Library

Psychiatry Research 299 (2021) 113845

Available online 2 March 2021

0165-1781/© 2021 The Authors. Published by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Short communication

Processing of an ambiguous time phrase in posttraumatic stress disorder:

Eye movements suggest a passive, oncoming perception of the future

M.C. Pfaltz

a,b,1,*, M.M. Plichta

c,1, C.J. Bockisch

a,d, L. Jellestad

b, U. Schnyder

a, K. Stocker

e,f,gaUniversity of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

bUniversity Hospital Zurich, Department of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry and Psychosomatic Medicine, Zurich, Switzerland

cDepartment of Psychiatry, Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, University Hospital, Goethe University, Frankfurt, Germany

dUniversity Hospital Zurich, Departments of Neurology, Ophthalmology, and Otorhinolaryngology, Zurich, Switzerland

eETH Zurich, Chair of Cognitive Science

fUniversity of Zurich, Institute of Psychology, Zurich, Switzerland

gUniDistance Suisse (Brig), Faculty of Psychology, Brig, Switzerland

A R T I C L E I N F O Keywords:

Posttraumatic stress disorder Eye movements

Time perception

A B S T R A C T

Metaphorically, the future can be perceived as approaching us (time-moving metaphor) or as being approached by us (ego-moving metaphor). Also, in line with findings that our eyes look more up when thinking about the future than the past, the future’s location can be conceptualized in upwards terms. Eye movements were recorded in 19 participants with PTSD and 20 healthy controls. Participants with PTSD showed downward and healthy controls upward eye movements while processing an ego/time-moving ambiguous phrase, suggesting a passive (time-moving) outlook toward the future. If replicated, our findings may have implications for the conceptualization and treatment of PTSD.

1. Introduction

People conceptualize their future in different ways: they either actively move toward it (ego-moving metaphor, “We are approaching the weekend”), or, passively, the future moves toward them (time- moving metaphor, “The weekend is approaching”) (Boroditsky, 2000;

Boroditsky and Ramscar, 2002; McGlone and Harding, 1998). In- dividuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often perceive their future as full of potential threats and trauma reminders they attempt to avoid (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Avoiding future events precludes an active movement towards the future – one reason why individuals with PTSD might view their future from a time-moving perspective. Additionally, PTSD patients’ frequent flashbacks and nightmares (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) – their being

“stuck in the past” (Holman and Silver, 1998) – might contribute to a time-moving future perspective.

An established (Richmond et al., 2012) assessment of the current time perspective of a person is to employ the ambiguous question: “Next Wednesday’s meeting has been moved forward two days. On what day will the meeting now take place?” (McGlone and Harding, 1998).

Conceptualizing “forward” as ego-moving, it means more in the future (“Friday”), while time-moving “forward” means closer to the present (“Monday”). Previous studies using the “Wednesday Question” (WQ) have used participants’ answers (Bender et al., 2010), which reflect deliberate processing, rather than someone’s initial perception. Meta- phorically, the future can be conceptualized in upward terms (“I’m afraid of what’s up ahead of us”) (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980). Oculo- motor studies show that we look at higher locations for future than for past events, when processing temporal words (Stocker et al., 2016) and thoughts (Hartmann et al., 2014).

Here, we recorded eye movements during processing of the critical ambiguous phrase (region of interest, ROI) of the WQ. We hypothesized that individuals with PTSD will show more downward eye movements than healthy controls, reflecting a time-moving perception of the future, moving toward the self (ocular downward path from Wednesday to Monday).

2. Methods

Nineteen participants with PTSD (mean age: 38.5 SD: 12.8; 79%

* Corresponding author at: University Hospital Zurich, 8091 Zurich, Switzerland.

E-mail address: Monique.pfaltz@usz.ch (M.C. Pfaltz).

1 These authors contributed equally to this work.

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Psychiatry Research

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/psychres

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113845 Received 14 July 2020; Accepted 27 February 2021

Psychiatry Research 299 (2021) 113845

2 female) and 20 healthy controls (without trauma exposure; mean age:

36.5, SD: 9.5; 60% female) participated in our experiment as part of a larger study on ocular mental time. Groups were comparable regarding sex ratio (chi-square =1.64; p =0.20) and age (t =0.56; p =0.58). The study was approved by the local ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained.

Participants were assessed for the presence of PTSD and any addi- tional mental disorders by the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS, (Müller-Engelmann et al., 2018; Weathers et al., 2013) and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I., German version 5.0.0 DSM-IV; Sheehan et al., 1998) that were administered by trained graduate students. Furthermore, measures of depression (Beck Depression Inventory, BDI; Hautzinger et al., 1994) and anxiety (State-Trait-Anxiety (STAI; Laux et al., 1981) were administered online.

Following previous research (e.g., Duffy and Feist, 2014), a computer screen instructed participants to not spend too much time thinking about the WQ and not to correct their initial, spontaneous response. Partici- pants then clicked “start listening to question,” upon which the question (German translation) was presented over headphones, while the screen remained empty. Thereafter, participants typed in their answer (“Monday” or “Friday”).

Monocular eye movements were recorded at 500 Hz using an Eye- Link 1000 remote camera tracking system (SR Research, Ontario Can- ada). A 9-point calibration and validation procedure were performed (error values below 0.5◦ were accepted), and drift correction was

performed prior to the experiment, using a fixation cross. Stimuli were presented on a 38 ×30 cm screen (1280 ×1024 pixels), 60 cm from the observer, using Matlab (The Mathworks, Natick, Massachusetts, U.S.A.) and the Psychtoolbox (Brainard, 1997; Kleiner et al., 2007; Pelli, 1997).

Participants were told that the eye tracker measures their pupil size (cover story). Eye position data was low-pass filtered (zero-phase, 50 Hz butterworth filter using the MatLab function filtfilt.m). Data during blinks were replaced by linear interpolation. We report eye position as pixel position on the computer monitor (29 pixels per degree, viewing distance: 60 cm).

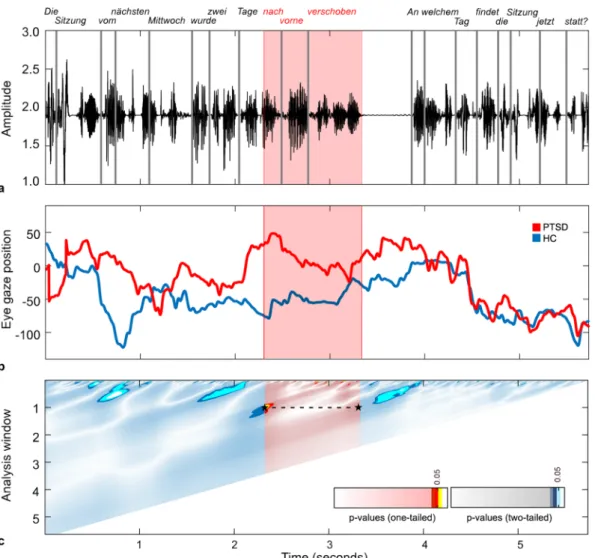

To test our hypothesis, data during the ambiguous part of the WQ was extracted, and regression analysis testing for a linear trend was performed for each participant. T-tests for independent data were used to compare the resulting Beta weights (as measure of eye gaze evoked by the critical phrase) between study groups (alpha: 5%; one-tailed). As an additional test for specificity of our hypothesis-driven analysis, we performed linear regression analyses to detect linear trends across the entire audio stimulation with all possible time-window-lengths. Length of the time window for slope analyses (Fig. 1c) was varied from 2–2888 sampling points (1–5776 ms) (y-axis). Analyses of time windows were moved across the complete time window (x-axis). T-tests comparing slope differences between study groups were performed for each time window length and onset (alpha: 0.05; two-tailed). Color code shows the corresponding p-values, with brighter colors representing more signifi- cant group differences.

Fig. 1. A: Audio sound wave. Gray lines represent word onsets of the German WQ. B: Mean vertical oculomotor position during processing of the WQ in the two study groups. C: Comparison of group-specific slopes dependent on the window-length and time of analysis. The ROI is highlighted in light red color. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

M.C. Pfaltz et al.

3. Results

In line with our hypothesis, online responses to our a-priori defined ROI (auditory processing of the ego/time-moving ambiguous phrase;

Fig. 1a) showed an oculomotor downward slope for PTSD individuals and upward slope for controls (t =1.90; df =37; p =0.03; Fig. 1b).

Additional analyses of all possible time-window lengths over the entire time perspective question confirmed the effect within our ROI (Fig. 1c).

To explore whether the downward slope observed in the PTSD group was related to specific symptoms of PTSD, we additionally calculated Spearman correlations between the slopes observed during the pre- defined ROI and the scores of the 4 CAPS subscales, measuring symp- toms of re-experiencing, avoidance behaviors, changes in mood and cognition, and symptoms of hyperarousal. None of these correlations reached significance (p’s >0.051).

4. Discussion

Our finding that individuals with PTSD show downward and healthy controls upward eye movements while processing an ego/time-moving ambiguous phrase, suggests that individuals with PTSD tend to pro- cess the future in time-moving terms (as approaching them), while healthy individuals applied an ego-moving perspective.

While encouraging a further exploration of the observed phenome- non, our findings need to be considered first steps in the assessment of how individuals with PTSD perceive time. Downward slopes during processing of the ambiguous phrase (suggesting a time-moving perspective) were unrelated to the severity of the four PTSD symptom clusters. This contradicts our theoretical assumptions on the mecha- nisms or symptoms that might underlie the observed finding. Future studies should thus not only aim at replicating our initial finding but also explore the factors contributing to a time-moving perspective in in- dividuals with PTSD. Moreover, our data do not indicate whether effects on eye gaze are specific to PTSD or whether they depend on depression and/or anxiety – as depressiveness and anxiety have (in healthy par- ticipants, at non-clinical levels) been linked to time-moving future thought (Richmond et al., 2012). Since our depression and anxiety data were confounded with group assignment (BDI: r =0.85; STAI: r =0.87), we could not disentangle these factors. Comparing patients with current major depressive disorder (MDD) to patients without current MDD, no significant differences in eye movement were evident (all ps >0.49). As a majority of patients with PTSD suffer from comorbid depression or anxiety (Kessler et al., 2005), future clinical studies into ocular mental time should also examine patients with depression or anxiety and no PTSD.

Finally, our findings need to be put into a cross-cultural perspective, as time is spatialized in many different ways among different cultures.

For example, the characterization of mental time lines running from past to present to future is culture dependent. Mental time lines can run from back (and downward) to front (and upward), or from left to right (Western and many other cultures); from right to left (e.g., Hebrew, Arabic); from top to bottom (especially Mandarin Chinese from Taiwan);

from East to West (in the Australian-Aboriginal Pormpuraawan com- munity, e.g., among the Kuuk–Thaayorre speakers); and from front to back (in users of Aymara, a language of the Andes) (Stocker, 2014;

Thones and Stocker, 2019). Thus, while research on the spatialization of ¨ the ego/time moving metaphor in other than Western cultures is scarce (Le Guen and Balam, 2012), it will likely vary across cultures, which precludes transcultural generalization of our findings.

Notwithstanding these limitations, if replicated in future studies, our initial finding might have implications for the conceptualization and treatment of PTSD; despite psychotherapeutic and pharmacological treatment options, many patients do not respond sufficiently or drop out of treatment (Bisson et al., 2013; Schnyder and Cloitre, 2015; Watts et al., 2013). Development of novel (culture-specific) interventions could, for instance, involve teaching patients to visualize their future in

an ego-moving mode. Here, the use of imagination exercises might be helpful. For example, patients could be asked to imagine every day and, later on, frightening future events, towards which they actively move and which they actively influence, e.g., by choosing between alternative versions of the future. During these exercises, patients’ eye movements could be recorded as they might benefit from biofeedback on how actively they are able to approach the future. Such treatment might reduce the patients’ tendency to become “stuck” in the past and promote a sense of control.

Funding

Part of this work was supported by the OPO foundation (Zurich, Switzerland) [no grant number]. This foundation had no involvement in study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in writing of this manuscript and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

M.C. Pfaltz: Conceptualization, Data curtion, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. M.M. Plichta:

Conceptualization, Data curtion, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. C.J. Bockisch: Conceptualization, Data curtion, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review

& editing. L. Jellestad: Conceptualization, Data curtion, Formal anal-

ysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. U. Schnyder:

Conceptualization, Data curtion, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. K. Stocker: Conceptualization, Data curtion, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review &

editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Natascha Benteler, Andrea Bizzeti (Phonogram Archive, University of Zurich), Josefine Halm, Lisa-Katrin Kaufmann, Annina Meyer, Muriel Nicolier, Lisa Schmidt, Michelle Steinemann, and Mar- igona Tomes for their help with the data collection and analyses.

References

American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, fifth ed. American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington, DC.

Bender, A., Beller, S., Bennardo, G., 2010. Temporal frames of reference: conceptual analysis and empirical evidence from German, English, Mandarin Chinese and Tongan. J. Cogn. Cult. 10, 283–307. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853710X531195.

Bisson, J.I., Roberts, N.P., Andrew, M., Cooper, R., Lewis, C., 2013. Psychological therapies for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003388.pub4.

Boroditsky, L., 2000. Metaphoric structuring: understanding time through spatial metaphors. Cognition 75 (1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-0277(99) 00073-6.

Boroditsky, L., Ramscar, M., 2002. The roles of body and mind in abstract thought.

Psychol. Sci. 13 (2), 185–189, 10.1111%2F1467-9280.00434.

Brainard, D.H., 1997. The psychophysics toolbox. Spat. Vis. 10 (4), 433–436. https://doi.

org/10.1163/156856897X00357.

Duffy, S.E., Feist, M.I., 2014. Individual differences in the interpretation of ambiguous statements about time. Cogn. Linguist. 25, 29–54.

Hartmann, M., Martarelli, C.S., Mast, F.W., Stocker, K., 2014. Eye movements during mental time travel follow a diagonal line. Consicious. Cogn. 30, 201–209. https://

doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2014.09.007.

Hautzinger, M., Bailer, M., Worall, H., Keller, F., 1994. Beck Depression Inventory [German Version]. Huber, Bern (Switzerland).

Holman, E.A., Silver, R.C., 1998. Getting “stuck” in the past: temporal orientation and coping with trauma. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 1146–1163. https://doi.org/10.1037/

0022-3514.74.5.1146.

Kessler, R.C., Chiu, W.T., Demler, O., Walters, E.E., 2005. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry 62 (6), 617–627.

Psychiatry Research 299 (2021) 113845

4 Kleiner, M., Brainard, D., Pelli, D., Ingling, A ., Murray, R., Broussard, C., 2007. What’s

new in psychtoolbox-3? Perception 36 (14), 1–16. ECVP Abstract Supplement.

Lakoff, G., Johnson, M., 1980. Conceptual metaphor in everyday language. Int. J. Philos.

Stud. 77 (8), 453–486. https://doi.org/10.2307/2025464.

Laux, L., Glanzmann, P., Schaffner, P., 1981. State-Trait-Angstinventar [German Version of Spielberger, et al.’s State-Trait-Anxiety Inventory]. Hogrefe, G¨ottingen (Germany).

Le Guen, O., Pool Balam, L.I., 2012. No metaphorical timeline in gesture and cognition among Yucatec Mayas. Front. Psychol. 3, 1–15.

McGlone, M.S., Harding, J.L., 1998. Back (or forward?) to the future: the role of perspective in temporal language comprehension. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. 24 (5), 1211–1223. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.24.5.1211.

Müller-Engelmann, M., Schnyder, U., Dittmann, C., Priebe, K., Bohus, M., Thome, J., Steil, R., 2018. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the German version of the clinician-administered PTSD scale for DSM-5. Assessment 27 (6), 1128–1138, 1073191118774840.

Pelli, D.G., 1997. The videotoolbox software for visual psychophysics: transforming numbers into movies. Spat. Vis. 10 (4), 437–442. https://doi.org/10.1163/

156856897X00366.

Richmond, J., Wilson, J.C., Zinken, J., 2012. A feeling for the future: how does agency in time metaphors relate to feelings? Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 42 (7), 813–823. https://doi.

org/10.1002/ejsp.1906.

Schnyder, U., Cloitre, M., 2015. Evidence Based Treatments for Trauma-Related Psychological Disorders: A Practical Guide for Clinicians. Springer International Publishing, Switzerland (U. Schnyder & M. Cloitre Eds.).

Sheehan, D., et al., 1998. Diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10.

J. Clin. Psychiatry. 59, 22–33.

Stocker, K., 2014. The theory of cognitive spacetime. Metaphor Symb. 29 (2), 71–93.

Th¨ones, S., Stocker, K., 2019. A standard conceptual framework for the study of subjective time. Conscious. Cogn. 71, 114–122.

Stocker, K., Hartmann, M., Martarelli, C.S., Mast, F.W., 2016. Eye movements reveal mental looking through time. Cogn. Sci. 40, 1648–1670. https://doi.org/10.1111/

cogs.12301.

Watts, B.V., Schnurr, P.P., Mayo, L., Young-Xu, Y., Weeks, W.B., Friedman, M.J., 2013.

Meta-analysis of the efficacy of treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Clin.

Psychiat. 74 (6), e541–e550. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.4088/JCP.12r08225.

Weathers, F.W., Bovin, M.J., Lee, D.J., Sloan, D.M., Schnurr, P.P., Kaloupek, D.G., Marx, B.P., 2013. The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5).

National Center for PTSD. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/PTSD/professional/assessment/

adult-int/caps.asp.

M.C. Pfaltz et al.