Understanding and Increasing Ethical Behaviour Through Mechanism Design

Volltext

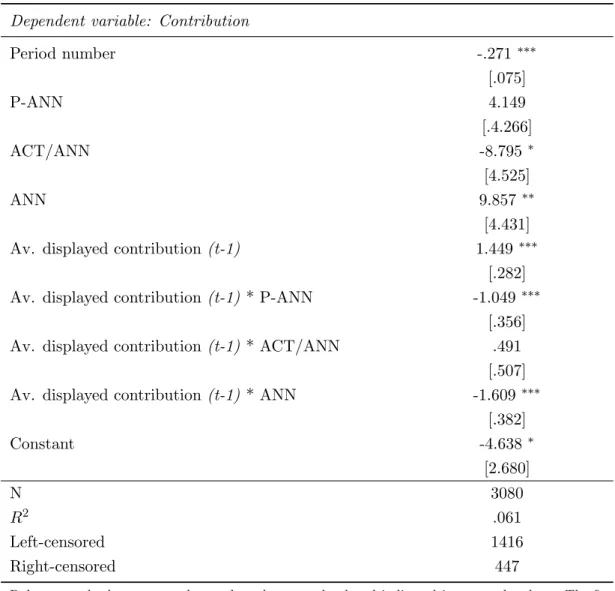

Abbildung

ÄHNLICHE DOKUMENTE

Expected Competences acquired after completion of the module: In this seminar, students learn to comprehend, present, critically evaluate and historically situate the work of leading

Hier sieht Ian Mulvany das große Problem, dass diese Daten eigentlich verloren sind für die Forschung und für die Community, wenn der Wissenschaftler die

Quelque chose de sain pour la récréation 1195?. 1195 Quelque chose de sain pour la récréation 1198 Tentations

Smoking as a public health matter is considered to be linked to “behavioural factors” (Neuhauser/Kreps 2010: 9) that can be improved by in- dividuals. Public health websites

Das Musical Catch me if you can, bekannt aus der gleichnamigen Verfilmung von Steven Spielberg mit Leonardo DiCaprio und Tom Hanks, ist am Montag, 11.2.2019 um 19.30 Uhr als

Lara DIAS SILVA Thema: S Kreativ in der Krise Preis: Preis der Vorjury. Sophia MAYUMI DIAS Thema: S Kreativ in der Krise Preis: Preis

Analysing the findings from field research in two sites in Eastern Nepal, Sunsari and Sankhuwasabha, 2 this report highlights boys’ and young men’s patterns of behaviour,

China views Brussels’ Asia policies with continued suspicion while the United States thinks the EU’s ‘soft power’ approach is simply not enough.. By Axel Berkofsky