Making Paris Work for Vulnerable Populations

Volltext

Abbildung

ÄHNLICHE DOKUMENTE

Drawing on empirical research from several disciplines, it examines patterns and dynamics of young people's risk taking, and explores concepts of risk culture and cultural learning,

Within this contribution we propose a method based upon the design structure matrix approach, which enables the identification of role aggregations, and examination of access

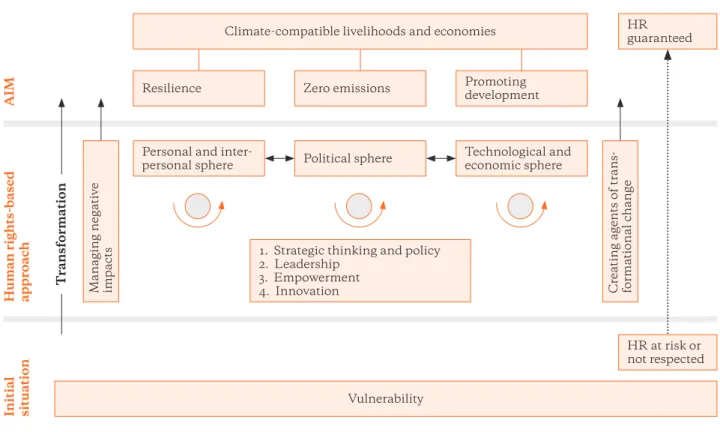

Künzel (2020) also applied the approach in assessing the contingency plan of African Risk Capacity. These two cases, only showcase two possibilities for the HRBA-CDRF’s

With ongoing climate change and extreme weather events increasing in severity and frequency insurance premiums may become unaffordable in future – leaving the poorest and

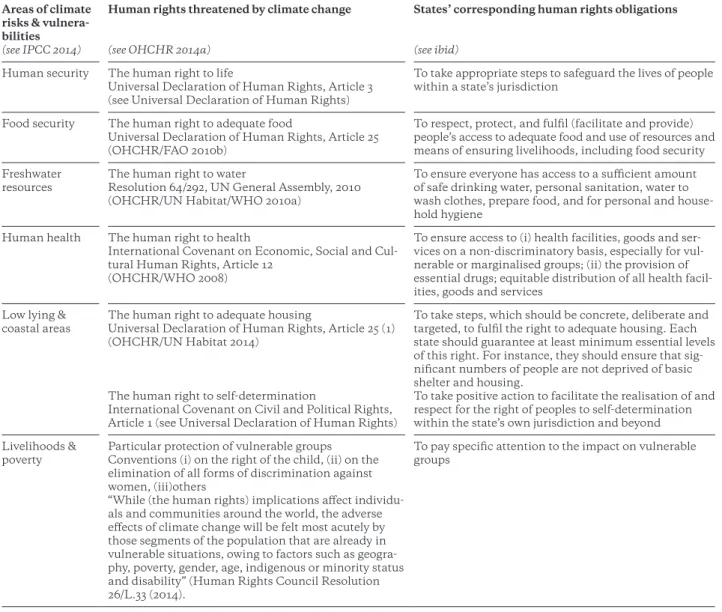

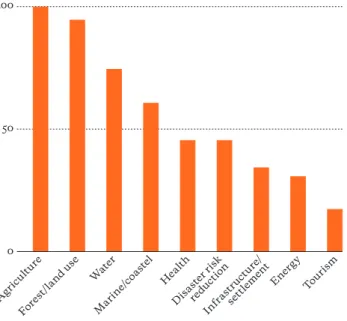

In order to be mindful of the poorest and most vulnerable populations, the call has been made for a pro-poor and human rights-based approach to climate risk insurance (CRI)

Building on the close collaboration with the Departments of Environmental Affairs (DEA) and Energy (DoE), together with the Independent Power Producers (IPP) Office, the Departments

The point of this is that when the light penetrates the layer of acrylic glass the light refraction on the surface of the photopaper is completely different from the effect when

Talk about the overwhelming consensus on the anthropogenic causes of climate change is opening the door to wider acceptance of climate science findings.. “The public” does