Language and W orld

S prache und W elt

32. Internationales Wittgenstein Symposium 32

ndInternational Wittgenstein Symposium

Kirchberg am Wechsel 9. - 15. August 2009

Beiträge

Papers

32. Internationales Wittgenstein Symposium

Kirchberg am Wechsel 2009

32

32

S prache und W elt Language and W orld

32. Internationales Wittgenstein Symposium Kirchberg am Wechsel 2009 Beiträge

Papers

Volker A. Munz Klaus Puhl Joseph Wang Hrsg.

Co-Bu-09:Co-Bu-07.qxd 04.06.2009 12:13 Seite 1

Sprache und Welt

Language and World

Beiträge der Österreichischen Ludwig Wittgenstein Gesellschaft Contributions of the Austrian Ludwig Wittgenstein Society

Band XVII

Volume XVII

Sprache und Welt

Beiträge des 32. Internationalen Wittgenstein Symposiums

9. – 15. August 2009 Kirchberg am Wechsel

Band XVII

Herausgeber Volker A. Munz Klaus Puhl Joseph Wang

Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Abteilung Kultur und Wissenschaft des Amtes der NÖ Landesregierung

Kirchberg am Wechsel, 2009

Österreichische Ludwig Wittgenstein Gesellschaft

Language and World

Papers of the 32

ndInternational Wittgenstein Symposium

August 9 – 15, 2009 Kirchberg am Wechsel

Volume XVII

Editors

Volker A. Munz Klaus Puhl Joseph Wang

Printed in cooperation with the Department for Culture and Science of the Province of Lower Austria

Kirchberg am Wechsel, 2009

Austrian Ludwig Wittgenstein Society

Distributors

Die Österreichische Ludwig Wittgenstein Gesellschaft The Austrian Ludwig Wittgenstein Society

Markt 63, A-2880 Kirchberg am Wechsel Österreich/Austria

ISSN 1022-3398 All Rights Reserved

Copyright 2009 by the authors

Copyright will remain with the author, rights to use with the society. No part of the material may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, and informational storage and retrieval systems without written permission from the society.

Visuelle Gestaltung: Sascha Windholz

Druck: Eigner Druck, A-3040 Neulengbach

Inhalt / Contents

On Intensional Interpretations of Scientific Theories

Terje Aaberge, Sogndal, Norway... 13 Wittgenstein, Dworkin and Rules

Maija Aalto-Heinilä, Joensuu, Finland... 17 Against Expressionism: Wittgenstein, Searle, and Semantic Content

Brandon Absher, Lexington, KY, USA ... 19 Modal Empiricism and Two-Dimensional Semantics

Gergely Ambrus, Miskolc, Hungary ... 22 Compositionality from a “Use-Theoretic” Perspective

Edgar José Andrade-Lotero, Amsterdam, The Netherlands... 25 Eine Überprüfung von Norman Malcolms Bemerkungen über die Verwundbarkeit unserer objektiven Gewissheiten

José Maria Ariso, Kassel, Deutschland ... 28 Wittgenstein and Skepticism About Expression

Stina Bäckström, Chicago, IL, USA ... 31 A Digitalized Tractarian World

Sun Bok Bae, Seoul, Korea ... 34 Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus – the Introduction of the Archetypal Sign of Logic

Diana Bantchovska, Durban, South Africa... 39 Language-Use as a Grammatical Construction of the World

Paulo Barroso, Braga, Portugal ... 42 Critique of Language and Sense of the World: Wittgenstein’s Two Philosophies

Marco Bastianelli, Perugia, Italy... 45 From the Prototractatus to the Tractatus

Luciano Bazzocchi, Pisa, Italy ... 48 Constructions and the Other

Ondrej Beran, Prague, Czech Republic... 51 Our ‘Form of Life’ Revealed in the Action of Language

Cecilia B. Beristain, Munich, Germany ... 54 Language as Environment: an Ecological Approach to Wittgenstein’s Form of Life

Pierluigi Biancini, Palermo, Italy... 56 Sprache als Kontinuum, Sprache als ‚Diskretum’ in der aristotelischen Physik

Ermenegildo Bidese, Trient, Italien ... 59 Neo-Expressivism and the Picture Theory

Nathanial Blower, Iowa City, IA, USA ... 62 Interpretation of Psychological Concepts in Wittgenstein

Antonio Bova, Lugano, Switzerland ... 64

Inhalt / Contents

Wittgenstein on Realism, Ethics and Aesthetics

Mario Brandhorst, Göttingen, Germany ... 66 Wittgenstein and Sellars on Thinking

Stefan Brandt, Oxford, United Kingdom... 69 Language and the World

Nancy Brenner, Bilthoven, Netherlands... 72 Approximating Identity Criteria

Massimiliano Carrara / Silvia Gaio, Padua, Italy... 75 Model-Theoretic Languages as Formal Ontologies

Elena Dragalina Chernaya, Moscow, Russia... 78 Language and Responsibility

Anne-Marie S. Christensen, Odense, Denmark... 81 Sidestepping the Holes of Holism

Tadeusz Ciecierski / Piotr Wilkin, Warsaw, Poland ... 84 Tractatus 6.3751

João Vergílio Gallerani Cuter, Brasilia, Brazil ... 87 Social Externalism and Conceptual Falsehood

Bolesław Czarnecki, Cracow, Poland ... 89 Perception, Language and Cognitive Success

Tadeusz Czarnecki, Cracow, Poland... 91 Therapy, Practice and Normativity

Soroush Dabbagh, Tehran, Iran ... 93 Sprache und Wirklichkeit in Nāgārjunas Mūlamadhyamakakārikā

Kiran Desai-Breun, Erfurt, Deutschland... 97 Referential Descriptions in Attitude Reports

Dušan Dožudić, Zagreb, Croatia... 100 The Differentiating Role Played by Double Negation in Linking Language to the World

Antonino Drago, Pisa, Italy ... 102 Correlation, Correspondence and the Bounds of Linguistic Behavior

Eli Dresner, Tel Aviv, Israel... 105 A Response to Child’s Objection to Common-Sense Realism

Olaf Ellefson, Toronto, Canada... 108 The Multiple Complete Systems Conception as Fil Conducteur of Wittgenstein’s Philosophy of Mathematics

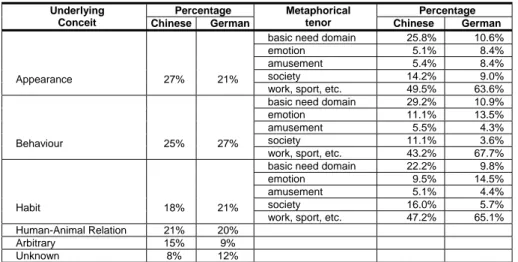

Mauro L. Engelmann, Belo Horizonte, Brazil ... 111 Umfasst Wittgensteins früher Bildbegriff das literarische Bild (bildliches Sprechen)?

Christian Erbacher, Bergen, Norwegen ... 114 Understanding Architecture as Inessential

Carolyn Fahey, Newcastle, United Kingdom ... 117 Cavell on the Ethical Point of the Investigations

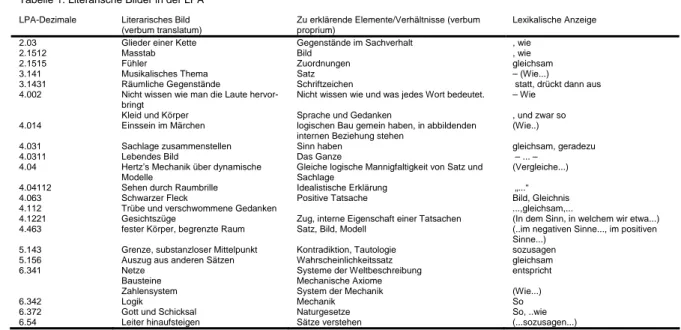

Matteo Falomi, Rome, Italy ... 120 Semiotische Dreiecke als Problem für den radikalen Konstruktivismus

August Fenk, Klagenfurt, Österreich... 123 Philosophical Pictures and the Birth of ‘the Mind’

Eugen Fischer, Norwich, United Kingdom ... 127 Über das Unaussprechliche beim frühen und späten Wittgenstein

Florian Franken, Berlin, Deutschland... 130 Is ‘a = a’ Apriori?

Wolfgang Freitag, Konstanz, Germany... 133 Das Wesen der Negation

Georg Friedrich, Graz, Österreich... 136

Inhalt / Contents

Wittgenstein Repudiates Metaphysical Chatter, Not Metaphysics per se

Earl Stanley B Fronda, Quezon City, Philippines... 139 A Study in Bi-logic (A Reflection on Wittgenstein)

Tzu-Keng Fu, Bern, Switzerland ... 142 Phenomenal Concepts and the Hard Problem

Martina Fürst, Graz, Austria... 145 Aspects of Modernism and Modernity in Wittgenstein’s Early Thought

Dimitris Gakis, Amsterdam, Netherlands ... 148 On the Origin and Compilation of ‘Cause and Effect: Intuitive Awareness’

Kim van Gennip, Groningen, Netherlands ... 151 The Philosophical Problem of Transparent-White Objects

Frederik Gierlinger, Vienna, Austria... 154 Private Sensation and Private Language

Qun Gong, Beijing, China ... 157 Thought Experimentation and Conceivable Experiences: The Chinese Room Case

Rodrigo González, Santiago, Chile... 160 The Argument from Normativity against Dispositional Analyses of Meaning

Andrea Guardo, Milan, Italy ... 163 Language and Second Order Thinking: The False Belief Task

Arkadiusz Gut, Lublin, Poland... 166 Schoenberg and Wittgenstein: The Odd Couple

Eran Guter, Jezreel Valley, Israel ... 169 Ian Hacking über die Sprachabhängigkeit von Handlungen und das „Erfinden“ von Leuten

Rico Hauswald, Dresden, Deutschland ... 172

‘Meaning as Use’ in Psychotherapy: How to Understand ‘You have my Mind in the Drawer of your Desk’.

John M. Heaton / Barbara Latham, London, United Kingdom ... 175 Form – Wirklichkeit – Repräsentation

Włodzimierz Heflik, Krakau, Polen... 178 Language Change and Imagination

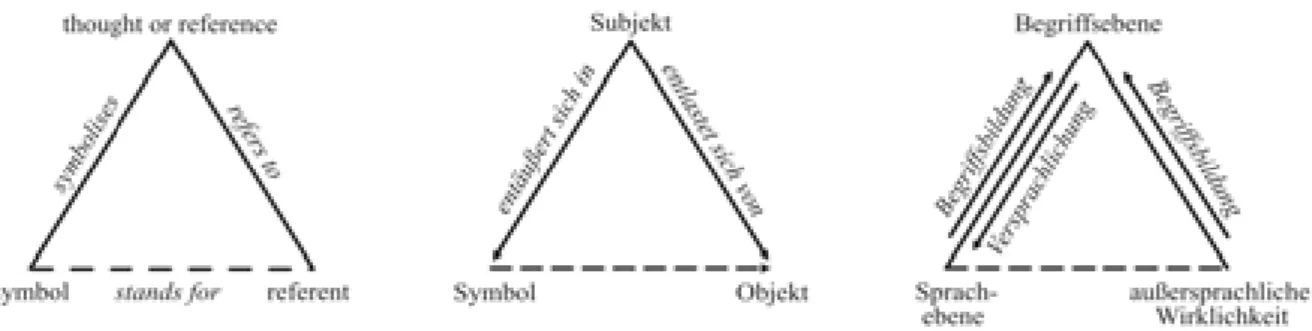

Christian Herzog, Klagenfurt, Austria... 181 A Lexicological Study on Animal Fixed Expressions

Shelley Ching-yu Hsieh, Taipei, Taiwan ... 184 Re-defining the Relation Between World-picture and Life-form in Wittgenstein’s On Certainty

Joose Järvenkylä, Tampere, Finland ... 187 Metaphysics of the Language and the Language of Metaphysics

Serguei L. Katrechko, Moscow, Russia ... 190 Zwei Dilemmata – McDowell und Davidson über Sprache, Erfahrung und Welt

Jens Kertscher, Darmstadt, Deutschland ... 193 John Divers on Quine's Critique of De Re Necessity

Antti Keskinen, Tampere, Finland... 196 From Practical Attitude to Normative Status: Defending Brandom's solution of the Rule-Following Problem

Matthias Kiesselbach, Potsdam, Germany ... 199 Second Thoughts on Wittgenstein’s Secondary Sense

Vasso Kindi, Athens, Greece ... 202 Reality and Construction, Linguistic or Otherwise: The Case of Biological Functional Explanations

Peter P. Kirschenmann, Amsterdam, The Netherlands ... 205 Zum Phaenomen der semantischen Negativität: (Nietzsche und Gerber)

Endre Kiss, Budapest, Ungarn... 208 Mind, Language, Activity: The Problem of Consciousness and Cultural-Activity Theory.

Leszek Koczanowicz, Wroclaw, Poland... 212

Inhalt / Contents

Beyond Mental Representation: Dualism Revisited

Zsuzsanna Kondor, Budapest, Hungary ... 215 Bertrand Russell’s Transformative Analysis and Incomplete Symbol

Ilmari Kortelainen, Tampere, Finland... 218 Practical Norms of Linguistic Entities

Anna Laktionova, Kiev, Ukraine... 221 Keeping Conceivability and Reference Apart

Daniel Lim, Cambridge, United Kingdom... 223 Marks of Mathematical Concepts

Montgomery Link, Boston, MA, USA ... 226 Wittgenstein, Turing, and the ‘Finitude’ of Language

Paul Livingston, Albuquerque, NM, USA ... 229

“Reality” and “Construction” as Equivalent Evaluation-Functions in Algebra of Formal Axiology:

A New Attitude to the Controversy between Logicism-Formalism and Intuitionism-Constructivism

Vladimir Lobovikov, Yekaterinburg, Russia ... 232 Metaphor: Perceiving an Internal Relation

Jakub Mácha, Brno, Czech Republic... 235 Language and the Problem of Decolonization of African Philosophy

Michael O. Maduagwu, Kuru, Nigeria ... 237

‘Viewing my Night’: a Comparison between the Thinking of Max Beckmann and Ludwig Wittgenstein

Dejan Makovec, Klagenfurt, Austria... 240 Similitudo – Wittgenstein and the Beauty of Connection

Sandra Markewitz, Bielefeld, Germany... 242 Ist die Intentionalität eine notwendige Bedingung für die Satzbedeutung?

Joelma Marques de Carvalho, München, Deutschland ... 245 Elucidation in Transition of Wittgenstein’s Philosophy

Yasushi Maruyama, Higashi-Hiroshima, Japan ... 248

"Facts, Facts, and Facts but No Ethics": A philosophical Remark on Dethroning

Anat Matar, Tel Aviv, Israel... 251 Morals in the World-Picture

Tobias Matzner, Karlsruhe, Germany ... 254 Is the Resolute Reading Really Inconsistent?: Trying to Get Clear on Hacker vs. Diamond/Conant

Michael Maurer, Vienna, Austria... 256 Ways of "Creating" Worlds

Ingolf Max, Leipzig, Germany ... 259 Die „Tatsache“ und das „Mystische“ - „wittgensteinische“ Annäherungen an Heimito von Doderers

Roman „Die Wasserfälle von Slunj“

Annelore Mayer, Baden, Österreich... 263 Die Musik als „ancilla philosophiae“ – Überlegungen zu Ludwig Wittgenstein und Nikolaus Cusanus

Johannes Leopold Mayer, Baden, Österreich... 266 The Points of the Picture: Hertz and Wittgenstein on the Picture Theory

Matthew McCall, Blacksburg, VA, USA ... 269 Language in Dreams: A Threat to Linguistic Antiskepticism

Konstantin Meissner, Berlin, Germany ... 272 A Privileged Access to Other Minds

Guido Melchior, Graz, Austria... 274 Textfraktale der nationalen Beziehungen im Kontext der Sprachspiele Ludwig Wittgensteins

Alexander Nikolajewitsch Melnikow, Barnaul, Russland... 277 Wittgenstein’s Conception of Moral Universality

Lumberto Mendoza, Quezon City, Philippines... 279

Inhalt / Contents

Language and Logic in Wittgenstein’s Tractatus, or Why “an Elementary Proposition Really Contains All Logical Operations in Itself” (TLP 5.47)

Daniele Mezzadri, Stirling, United Kingdom... 282 Philosophy and Language

Karel Mom, Amsterdam, Netherlands... 285 A Contribution to the Debate on the Reference of Substance Terms

Luis Fernández Moreno, Madrid, Spain... 288 Logic Degree Zero: Intentionality and (no[n-]) sense in Wittgenstein’s Tractatus

Anna A. Moser, New York, NY, USA ... 291 Zur Frage nach dem „Verhältnis der Teile des Urteils“ – Freges funktionale Analyse von Prädikaten

Gabriele Mras, Wien, Österreich... 294 Sensations, Conceptions and Perceptions: Remarks on Assessability for Accuracy

Carlos M. Muñoz-Suárez, Cali, Colombia... 297 Davidson on Desire and Value

Robert H. Myers, Toronto, Canada... 300 How May the Aesthetic Language of Artwork Represent Reality?

Dan Nesher, Haifa, Israel... 303 Moore’s Paradox and the Context Principle

Yrsa Neuman, Åbo, Finland... 308 Rigidity and Essentialism

Joanna Odrowąż-Sypniewska, Warsaw, Poland ... 310 Concatenation: Wittgenstein’s Logical Description of the Possible World

Jerome Ikechukwu Okonkwo, Owerri, Nigeria ... 313 Ethics and Private Language

Sibel Oktar, Istanbul / Halil Turan, Ankara, Turkey... 316 MacIntyre and Malcolm on the Continuity Between the Animal and the Human

Tove Österman, Uppsala, Sweden ... 318 The Thought (Gedanke): the Early Wittgenstein

Sushobhona Pal, Calcutta, India... 320 Searle on Representation: a Relation between Language and Consciousness

Ranjan K. Panda, Mumbai, India ... 322 Language and World in Wittgenstein: The True Social Bonding

Ratikanta Panda, Mumbai, India... 325 Language and Reality: A Wittgensteinian Reading of Bhartrhari

Kali Charan Pandey, Gorakhpur, India ... 327 Wittgenstein on the Self-Identity of Objects

Cyrus Panjvani, Edmonton, Canada... 330 Husserl, Wittgenstein, Apel: Communicative Expectations and Communicative Reality

Andrey Pavlenko, Moscow, Russia... 332 Aussage und Bedeutung. Skizze einer postanalytischen Bedeutungstheorie

Axel Pichler / Michael Raunig, Graz, Österreich... 335 Life and Death of Signs and Pictures: Wittgenstein on Living Pictures and Forms of Life

Sabine Plaud, Paris, France ... 338 Maps vs. Aspects: Notes on a Radical Interpretation

Ákos Polgárdi, Budapest, Hungary ... 341 Meaning without Rules: Language as Experiential Identity

Donald V. Poochigian, Grand Forks, ND, USA... 343 Action, Morality and Language

Marek Pyka, Cracow, Poland... 346

Inhalt / Contents

Structured Language Meanings and Structured Possible Worlds

Jiří Raclavský, Brno, Czech Republic ... 349 On the Explanatory Power of Davidson’s Triangulation

Franz J. Rainer, Innsbruck, Austria... 351 Vom Bildspiel zum Sprachspiel – Wieviel Kompositphotographie steckt in der Logik der Familienähnlichkeit?

Ulrich Richtmeyer, Potsdam, Deutschland ... 354 Zur Beschreibung der Funktion von Wahrheitsbedingungen

Stefan Riegelnik, Wien, Österreich ... 358 Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Methods in On Certainty

Brian Rogers, Irvine, CA, USA... 360 Cubes, Clouds & Reading the Philosophical Investigations

Rebekah Rutkoff, New York, NY, USA ... 363 History and Objects: Antonio Gramsci and Social Ontology

Alessandro Salice, Graz, Austria ... 367 Peirce on Colour (with Reference to Wittgenstein)

Barbara Saunders, Leuven, Belgium ... 370 Many-Valued Approach to Illocutionary Logic

Andrew Schumann, Minsk, Belarus ... 373 External Reference and Residual Magic

Paul Schweizer, Edinburgh, United Kingdom ... 376 The Linguistic Optimism: On Metaphysical Roots of Logic in Wittgenstein’s Tractatus

Marcos Silva, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil ... 379 Wittgenstein, Scepticism and Contextualism

Rui Silva, Azores, Portugal ... 382 Social Construction of Scientific Knowledge: Revisiting Searlean notion of Brute and Institutional Facts

Vikram Singh Sirola, Mumbai, India... 385 Wittgenstein versus Hilbert

Hartley Slater, Crawley, Australia ... 388 The World as States of Affairs in Wittgenstein and Armstrong

Alexandr Sobancev, Yekaterinburg, Russia ... 391 Die Kritik der Metaphysik im Werk L. Wittgensteins „Philosophische Untersuchungen“

Paul Antolievich Stolbovskiy, Barnaul, Russland... 393 Wittgenstein, Reflexivity and the Social Construction of Reality

Gavin Sullivan, Melbourne, Australia ... 395 The Topology of Existential Experience: Wittgenstein and Derrida (Between Reality and Construction)

Xymena Synak-Pskit, Gdańsk, Poland ... 398 Partizipation in virtuellen Welten

Sabine Thürmel, München, Deutschland... 401 Wittgenstein, Brandom und der analytische Pragmatismus

Stefan Tolksdorf, Berlin, Deutschland... 404 Searle on Construction of Reality: How We Construct Chairmen and Don’t Construct Chairs

Pavla Toracova, Prague, Czech Republic ... 409 In Pursuit of Ordinary: Performativity in Judith Butler and J. L. Austin

Aydan Turanli, Istanbul, Turkey ... 412 Crispin Wright’s Antirealism and Normativity of Truth

Pasi Valtonen, Tampere, Finland... 415 Was Wittgenstein a Normativist about Meaning?

Claudine Verheggen, Toronto, Canada ... 418

Inhalt / Contents

Should Essentialism about Laws of Nature Imply Strong Necessity?

Miklavž Vospernik, Maribor, Slovenia ... 421 On the Linguistic Turn, Again: A Rortian Note on the ‘Williamson/Hacker-Controversy’

Timo Vuorio, Tampere, Finland ... 424

„Es ist ein Beispiel, bei dem man Gedanken haben kann.“: Wittgenstein liest Hebel

David Wagner, Wien, Österreich ... 427 The Interlocutor Equivocation

Ben Walker, Norwich, United Kingdom... 430 Unshadowed Anti-Realism

Adam Wallace, Cambridge, United Kingdom... 433 No Nonsense Wittgenstein

Thomas Wallgren, Helsinki, Finland ... 436 Und das Selbst gibt es doch – Versuch der Verteidigung eines umstrittenen Konzepts

Patricia M. Wallusch, Frankfurt am Main, Deutschland ... 439 Cognition in the World? Functionalism and Extended Cognition

Sven Walter / Lena Kästner, Osnabrück, Germany... 442 Kein Denken ohne Reden? Anmerkungen zu einigen Argumenten für den begrifflichen Zusammenhang

von Intentionalität und Sprachfähigkeit

Heinrich Watzka, Frankfurt am Main, Deutschland... 445 Should the Language of Logic Dictate Reality?

Paul Weingartner, Salzburg, Austria... 448 Bedeutungserlebnis and Lebensgefühl in Kant and Wittgenstein: Responsibility and the Future.

Christian Helmut Wenzel, Taipei, Taiwan ... 451 Wittgenstein’s Activity: The Tractatus as an “Esoteric” Defense of Poetry

John Westbrook, Milwaukee, WI, USA ... 454 A Note on Wittgenstein’s Tractatus and Tolstoy’s Gospel in Brief

Peter K. Westergaard, Copenhagen, Denmark ... 456 Wittgenstein and the Unwritten Part of the Tractatus

Feng-Wei Wu, Taipei, Taiwan... 459 Though This Be Language, yet There Is Reality in’t: Prichard and Wittgenstein on Ethics.

Anna Zielinska, Grenoble, France ... 461

On Intensional Interpretations of Scientific Theories

Terje Aaberge, Sogndal, Norway

taa@vestforsk.no

The picture theory from Wittgenstein’s Tractatus logico- philosophicus provides a correspondence principle for the semantics of a formal language that in contrast to Tarski’s extensional interpretation scheme, can be represented by maps from the domain to the language. It makes possible intensional interpretations of the predicates of the lan- guage of discourse for a domain consisting of physical objects or systems. The aim of this paper is to outline the basis for such an interpretation and explain how it can be extended to a language of discourse for the properties of the physical systems.

1. Introduction

A first order formal language has of the following elements:

• Vocabulary

- Names, Variables, Predicates - Logical constants

• Rules of syntax

• Sentences and formulae

• Logical axioms

• Rules of deduction

• Ontology - Axioms

- Terminological definitions

• Interpretation (semantics)

The vocabulary consists of words with different syntactic roles and semantic values that are used to formulate sen- tences and formulae according to the syntactic rules. The logical axioms limit the scope of the logical constants, while the ontology axioms both provides the language with a semantic structure by being implicit definitions of the primary terms of the vocabulary and a model of the domain picturing its structural properties. Secondary terms that serve to facilitate the discourse are introduced by termino- logical definitions.

Excluding the interpretation we are left with a formal system, i.e. a formal language is a formal system supplied with an interpretation. The interpretation is relating the primary terms of the vocabulary to external ‘objects and actions’.

The standard way of providing a formal language with an interpretation is extensional and due to Tarski (1983, ch. VIII). If the domain of discourse consists of a set of (physical) systems, then a name denotes an individual system, a one-place predicate denotes a set of systems to which the predicate apply, a two-place predicate the set of pairs of ordered systems to which the predicate apply etc.

The semantics is thus defined by a map that maps the names to the individual systems and the predicates to the set consisting of sets of individuals, sets of ordered pairs of individuals etc.

Russel’s antinomy highlighted a problem threatening extensional interpretations. To avoid this problem at the outset Wittgenstein (1961) in Tractatus introduces the picture theory as a basis for the interpretation by corre- spondence with respect to the metaphysical assumption of logical atomism. A picture of a system can be seen as the image of a map from the domain to the language. I will use

this to outline a scheme for intensional interpretations of scientific theories in the framework of first order languages.

The restriction to first order makes it necessary to decompose the language in two coupled first order lan- guages, an object language in which to describe the em- pirical facts about the systems of the domain and a prop- erty language in which to describe the properties of sys- tems (Aaberge 2007). The reason for this separation is the need to quantify over physical systems and properties alike, but not in the same propositions. The distinction between the two languages captures scientific practice. In the object language a system is directly referred to, while in the property language the reference is indirect; it is given by means of identifying properties that are pos- sessed by the system. The distinction is exemplified by the sentences “the water in bottle 3 is 5°C” and “5°C is a tem- perature” in the object and property language respectively.

Here 5°C is a predicate of the first kind in the object lan- guage and a name in the property language.

2. The object language

Observations, operational definitions and observables The object language applies to a domain consisting of physical systems. Physical systems possess properties and the attribution of a property to an individual system constitutes an atomic fact about the system. It is ex- pressed by an atomic proposition, i.e. true atomic proposi- tions are statements about observed atomic facts. The observations of atomic facts all involve the use of a stan- dard of measure. The result of an observation follows from a comparison between a representation of the standard and the system. It determines a value from the standard, a predicate of the first kind.

Observations/measurements are based on opera- tional definitions, i.e. definitions that specify the applied standard of measure, the laws/rules on which the meas- urements are based and the instruction of the actions to be performed to make a measurement. The operational defini- tions are formulated in a separate language. They provide intensional interpretations of the predicates expressing results of observations. The measurement of the colour of a system is an example. The measuring device is then a colour chart where each of the colours is named and the rule of application is to compare the colour of the system with the colours on the colour chart and pick out the one identical to the colour of the system. The name of the col- our picked denotes the result of the measurement.

Each operational definition is symbolised by an ob- servable that simulates the act of observation; the observ- able is an injective map between the domain and the set of predicates (of the first kind) that maps a system to the predicate representing a property possessed by the sys- tem (Piron 1975). The set of possible values of an observ- able represent mutually exclusive properties of the sys- tems of the domain; no two properties corresponding to different values of the same observable can be possessed by any system. A system cannot at the same time weight 1 kg and 2 kg. Weight is therefore an observable. Other

On Intensional Interpretations of Scientific Theories / Terje Aaberge

examples of observables are position in space, number of systems in a given container and colour of systems.

Names, predicates of the first kind and truth

Let L(D;N∪V,P1∪P2) stand for the object language for a domain D. N denotes the set of names, V the set of vari- ables, P1 the set of predicates of the first kind and P2 the set of predicates of the second kind1. The distinction be- tween predicates of the first and second kind is semantic and made possible by the intensional interpretation. The names of the systems are given by a map ν,

( )

d d N;D

: → ν

ν

that to a system d in the domain D associates the name n by ν

( )

d=n. ν is an isomorphism; by convention, there is a unique name for every system and there is exactly the same number of names and systems.Each observable δ determines an atomic fact about a system d∈D by

( )

dd

; P D

: → 1 δ

δ

For each δ there exists a unique (injective) map π de- fined by the condition of commutativity of the diagram

(1)

1

→π

↑ ν δ

N P

D

i.e. π

( ) ( )

ν( )

d =δd,∀d∈DThe diagram relates the simulation of measurements de- termining atomic facts assigning a property to a system and the formulation of an atomic sentence expressing such a fact by the juxtaposition pn of the name n referring to the system d and the predicate p referring to the prop- erty, i.e. if π ν

( ) ( )

d = δ( )

d , for ν( )

d=n and π( )

n =p. Thecommutativity condition π

( ) ( )

ν( )

d =δd is thus the truth con- dition of the object language. It equates a proposition about the system d with a statement of the result of a measurement on d with respect to the observable δ.The Tarski interpretation can be derived from the above interpretation. By taking the inverse images of the predicates of the first kind with respect to the observables we get the extensions of the predicates. The opposite is however, not the case. The reason is that intensional defi- nitions contain much more information than extensional enumerations. In particular, operational definitions give meaning to predicates of the first kind at the outset while those of the second kind are introduced by terminological definitions.

Predicates of the second kind

One distinguishes between two kinds of observables refer- ring to two kinds of properties, properties that do not change in time and thus serves to identify the system, and properties that change. The corresponding observables are identification and state observables respectively.

The systems can be classified with respect to the identification observables. One starts with one of the ob- servables and uses its values to distinguish between the

1 In this paper the domain D is considered to consist of a set of systems with properties but without relations between them. There are then no two- and higher-ary predicate in the object language.

systems to construct classes. Thus, one gets a class for each value of the observable, the class of systems that possess the particular property, e.g. the class of all red systems, the class of all green systems etc. The procedure can be continued recursively until the set of identification observables is exhausted. The result is a hierarchy of classes with respect to the set inclusion relation. The basic entities of the classification are the leaf classes.

The classes are referred to by predicates of the se- cond kind which thus are ordered naturally in a taxonomy that constitutes a linguistic representation of the classi- fication. The satisfaction conditions defining the classes are intensional definitions of the predicates of the second kind. They are of the form

1 1 1 2 1 1

2 1 2 2 2 2

1 2

m m

k k k m k

pn p n p n ... p n pn p n p n ... p n

pn p n p n ... p n

= ∧ ∧ ∧

= ∧ ∧ ∧

= ∧ ∧ ∧

i i

where p is the predicate of the second kind referring to the class defined by the satisfaction condition, p1, p2, p3, … pm

are the values of the different observables and n1, n2, … nk, stand for the names of the systems for which the atomic propositions are true. The set of intensional defini- tions constitute terminological definitions belonging to the ontology of the language.

In the framework of the property language the sub- ject-predicate form of the atomic propositions whose func- tion is to attribute a property to a system can be consid- ered fundamental. Seemingly atomic propositions like “pn”

where p is a predicate of the second kind are only abbre- viations of sentences being conjunctions of atomic sen- tences. For example the sentence “S-2003 is a Car” hides the description of what falls under the concept referred to by the predicate of the second kind “Car”.

3. Property Languages Properties

Predicates of the first kind refer to properties of systems. A property is something in terms of which a system mani- fests itself and is observed, and by means of which it is characterised and identified. To an observer a system appears as a collection of properties. The properties of a system are thus in a natural way mentally separated from the system. The separation is made possible by the fact that the ‘same’ property is possessed by more than one system. It is expressed by the commutativity of the follow- ing diagrams

(2) δ ↑ ρ

→ ε

P1

D E i.e.δ

( )

d =ρ( )

ε( )

d ,∀d∈Dwhere E is the abstract representation of the set of proper- ties of the systems in D; the ε are injective maps that simulates the ‘mental’ separation of properties from the systems. In the case of coloured systems for example, the condition of commutativity means that if a system appears as red then it possesses the property redness. It is as- sumed that each predicate of the first kind refers to a unique potential property.

On Intensional Interpretations of Scientific Theories / Terje Aaberge

The property space E is a construction character- ised by the diagram. The E chosen is a natural extension of the set of properties that can be associated to the sys- tems of the domain as reflected in the set of predicates available in the standards of the operational definitions..

The maps ρ →:E P ; e1 ρ

( )

e can be considered as naming maps for the properties, e.g. a point in abstract space is named by a set of coordinates. To describe the properties we need a formal language, the property lan- guage L(E,P1∪W,Q), were P1 denotes the set of names, W the set of variables and Q the set of predicates. The prop- erty language is associated with the diagrams(3) φ

→

↑ ρ χ

P1 Q

E

The symbolic entities of E also belong to the property lan- guage. The maps ρ thus symbolises the kinds of meas- urements inside the language.

Ontologies

The ontology of the property language is a set of defi- nitions relating the terms of the vocabulary. It consists of an axiom system giving implicit definitions of what is cho- sen to be the primary terms and a set of terminological definitions introducing secondary terms which serves to simplify the discourse. The axioms are formalised ac- counts of the operational definitions which constitute a basis for the interpretation of the primary terms. The axi- oms define a semantic structure that pictures structural properties of the domain as seen through the operational definitions (Blanché 1999).

The Theory of Special Relativity offers an example for how operational definitions impose an axiomatic struc- ture on the property language. It is derived from an opera- tional definition of time and distance measurements based on a definition of simultaneity of distant events with respect to a given observer, the physical law claiming the velocity of light to be constant and independent of the velocity of the emitting source and the Principle of Relativity which postulates that the laws of physics are the same in all iner- tial frames of reference. Presently, the standard unit of time defines the second to be 9 192 631 770 periods of the radiation emitted from the transition between two hyperfine levels in the ground state of Caesium 133. Moreover, 1 meter is equal to the distance covered by a light ray in empty space in 1/299 792 458 seconds. Length measure- ments are thus based on time measurements.

The axioms of the property language express the content of the operational definitions which constitute the basis for empirical investigations. Their truth can therefore not be ascertained through empirical investigations. They are “hinge” propositions expressing statements about structural properties of the property language that reflects structural properties of the domain as seen through the

“lenses” of the operational definitions (Wittgenstein 1975).

The object language can only be indirectly tested by means of the models of systems of the domain formulated in the language.

4. Theories

A theory for a given domain is the juxtaposition of an ob- ject language and a property language. Because of their association the triples of observables ,δ πandρconstitute the bridges between the object language and the property language with the observables δ as the central parts. The diagrams

(4)

π φ

→ →

↑ ν δ ↑ ρ χ

→ ε

N P1 Q

D E

i.e. the composition of the diagrams (1), (2) and (3), ex- presses the structure of a scientific theory.

The commutativity of the diagrams (1) and (2) de- fines a unique π and ρ for each δ and ε. They all ex- press the attribution of a property to a system and there- fore represents the act of measurements. They will all be referred to as observables. Though their function differs the observables in a triple are therefore also given the same name. Colour is an example. Thus, while δ, by

( )

d redδ = associates the colour red to a system d,

( )

n redπ = stands for the atomic proposition “n is red”,

( )

d rednessε = claims that the system possesses the property redness and ρ

(

redness)

=red gives the name to the property. The observation that a system is red ex- pressed by the sentence “n is red” is therefore to be inter- preted as expressing that the system whose name is n possesses the property redness. This interpretation is justified by the commutativity of the diagram (4). The dia- gram thus shows how the semantic of the property lan- guage is based on the operational definitions.5. Concluding Remarks

When Wittgenstein returned to philosophy in 1929 he started with the intention to revise Tractatus logico- philosophicus. He had become aware of its shortcomings as regards some of his initial objectives. In particular, he had discovered that the symbolism of Tractatus, the truth- false notation, did not exclude the construction of nonsen- sical sentences like “x is red and x is green” (Marion 1998).

This forced him to abandon one of the pillars of Tractatus, the thesis that atomic sentences are independent (Trac- tatus 5.134).

I have made two proposals that make it possible to avoid some of Wittgenstein’s own objections to the Trac- tatus. I have considered the language of discourse for a scientific domain to be the juxtaposition of two separate but interdependent languages; moreover, the definition of the observable by mutual exclusiveness imposes a restric- tion on the syntax that goes outside the purely truth func- tional logic. It implies that sentences like “p n1 ∧p n2 ”, where p1 and p2 are different predicates of the first kind belonging to the same observable, are necessarily false since at least one of the atomic sentences in the conjunc- tion must be false.

On Intensional Interpretations of Scientific Theories / Terje Aaberge

The realisation that there are constructions in lan- guage, outside the scope of truth-functional logic forced Wittgenstein to extend his investigations. He started to look at the different functions of natural language and in- troduced the notion of language game to account for its semantic foundation. Language is correctly applied if the discourse satisfies the rules of the game (Wittgenstein 1968).

In a language of the kind I am proposing, there are different kinds of rules that fall under the category of lan- guage game, the syntactic rules, deduction rules and the rules that the axioms of the property language imposes on the application of the primary terms. In addition, there are meta rules imposed by the operational definitions deter- mining the interpretation of the primary terms as well as meta rules determining the semantics of the property lan- guage. It is clear that these different rules are at least partly interdependent. This interdependency should be analysable along the lines of Investigations and On Cer- tainty.

I hope to have shown that a coherent intensional in- terpretation can be made of the framework of a scientific theory. To make a comprehensive extensional interpreta- tion seems however, to be more difficult if at all possible because the underlying conceptual model of the domain and the direction of the interpretation map does not allow for the construction of commutative diagrams.

Literature

Aaberge, Terje 2008 : The 31st International Wittgenstein Sympo- sium

Blanché, Robert 1999: L’axiomatique. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France

Marion, Mathieu 1998: Wittgenstein, Finitism, and the Foundations of Mathematics. Oxford: Clarendon Press

Piron, Constantin 1975: Foundations of Quantum Physics. Boston:

Benjamin Inc.

Tarski, Alfred 1983: Logics, Semantics, Metamatematics. Indian- apolis: HackettPublishing Company, Inc.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig 1961: Tractatus logico-philosophicus. Lon- don: Routledge and Kegan Paul

Wittgenstein, Ludwig 1968: Philosophical Investigations. Oxford:

Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig 1975: On Certainty. Oxford: Blackwell Pub- lishers Ltd.

Wittgenstein, Dworkin and Rules

Maija Aalto-Heinilä, Joensuu, Finland

mjaalto@cc.joensuu.fi

1. Introduction

In legal theory, there exists a continuing controversy about the nature and status of legal rules. According to some theo- rists, law is essentially a matter of rules (see e.g. Hart 1994);

whereas others claim that rules form only a part of law, or that rules are only a source of law but do not by themselves determine the outcomes of judges’ decisions (see e.g.

Tushnet 1983). From the point of view of Wittgenstein’s remarks on rule-following, some concepttions about rules found in this debate look very strange. One example is Ronald Dworkin’s famous separation of rules from legal principles. My aim in this paper is to point out, with the help of Wittgenstein, the oddness of Dworkin’s definition of legal rules.

2. Dworkin’s distinction between rules and principles In his article “The Model of Rules I” (Dworkin 1977, pp. 14- 45), Dworkin introduced a distinction that has become a commonplace in legal theory. He argues that a positivistic conception, according to which law is just a system of rules (which can be demarcated from other rule-systems by some formal criterion), is wrong. Dworkin claims that

when lawyers reason or dispute about legal rights and ob- ligations, [. . . ] they make use of standards that do not function as rules, but operate differently as principles, policies, and other sorts of standards. [Positivism’s] cen- tral notion of a single fundamental test for law forces us to miss the important roles of these standards that are not rules. (Dworkin 1977, p. 22)

How do rules differ from principles (and other standards that are not rules)? According to Dworkin,

The difference between legal principles and legal rules is a logical distinction. Both sets of standards point to par- ticular decisions about legal obligation in particular cir- cumstances, but they differ in the character of the direc- tion they give. Rules are applicable in an all-or-nothing fashion. If the facts a rule stipulates are given, then either the rule is valid, in which case the answer it supplies must be accepted, or it is not, in which case it contributes noth- ing to the decision. (Dworkin 1977, 24).

Thus, rules are something that, if they are valid, “dictate the result, come what may” (ibid., 35). Dworkin illustrates their nature by comparing them to the rules of a game. For ex- ample, in baseball it is a rule that if a batter has had three strikes, he is out. The referee of the game cannot consis- tently hold that this is an accurate rule of the game, and at the same time decide that some batter can have four strikes.

Of course, there might occur some exceptional circum- stances which allow a batter to have an extra strike; but according to Dworkin (and this is the feature that interests us in his account of rules), an accurate statement of the rule would take all exceptions to the rule into account. Any for- mulation of a rule that does not state all the exceptions would be “incomplete”. In the same way, if it is a legal rule that a will is invalid unless signed by three witnesses,

then it cannot be that a will has been signed by only two witnesses and is valid. The rule might have exceptions,

but if it does then it is inaccurate and incomplete to state the rule so simply, without enumerating the exceptions. In theory, at least, the exceptions could all be listed, and the more of them that are, the more complete is the statement of the rule. (Dworkin 1977, 25)

Principles, on the other hand, do not dictate a particular result (even if they clearly are applicable to a given case).

Sometimes a principle like ‘No man may profit from his own wrong’ can be the ground for decision (as in the famous case Riggs vs. Palmer, in which a grandson did not inherit his grandfather because he had murdered the latter), whereas in other cases a man may be allowed to profit from his own wrong (as e.g. in a case where one can enjoy the benefits of a new job even though one got it by breaching a contract with one’s former employer). In short, a legal princi- ple “states a reason that argues in one direction, but does not necessitate a particular decision” (Dworkin 1977, 26)

3. A Wittgensteinian critique

Dworkin’s distinction between rules and principles, although enormously influential, has been criticised as well. The aim of the critics has mainly been to show that there is no reason why positivism couldn’t include principles in their account of law. (See e.g. Hart 1994, 238-276) Yet legal theorists seem not to have paid attention to the astonishing idea, implicit in Dworkin’s account, that there could be such a thing as a complete expression of a rule, which leaves absolutely no doubt about its correct application. What can Dworkin mean by such a thing?

A rule that would fulfil the theoretical requirement of completeness should have to be formulated in a language which is totally unambiguous: all the words used in the rule- formulation should have determinate, clear-cut meanings.

Thus, there could not be any uncertainty about what e.g.

‘signature’ or ‘witness’ means. This means that the formula- tion of the rule should have to take into account all possible exceptional circumstances – situations in which, for exam- ple, a will is invalid even though signed by three witnesses (because one witness is e.g. drugged). As we saw, Dworkin indeed thinks that such a complete statement of a rule is possible.

Now as is well-known, Wittgenstein in his Philoso- phical Investigations reminds us that many of our concepts have no clear boundaries. A famous example is that of a game: if we look at all the various things that are called games, we find that there is nothing they all have in com- mon, but see “a complicated network of similarities overlap- ping and criss-crossing” (PI 67). “The concept ‘game’ is a concept with blurred edges.” (PI 71) However, this is not to say that we cannot give determinate meanings to our con- cepts – Wittgenstein admits that this is possible for particular purposes (see PI 69). But Dworkin seems to require from legal rules more than this; he seems not to want precision for some particular purpose only, but absolute precision.

Wittgenstein tries to show this to be a confused requirement.

Let us look at Dworkin’s example of an unambiguous legal rule, the one that states that a will is invalid unless signed by three witnesses. Here, it seems, we can lay down in advance what all the terms mean so that a judge can

Texts Do Not Reflect Outer Reality. What Do They Do then? / Krzysztof Abriszewski

demarcate valid wills from invalid ones, “come what may”.

But as H.L.A. Hart points out, even the most innocent- looking term of this rule, ‘signature’, can cause problems.

What if the person who signs a will writes down only his initials? Or if he signs his name on the top of the first page and not on the bottom of the last page? Or if someone else guides his hand? Or if he uses a pseudonym? (Hart 1994, p.12) Dworkin would of course answer that a complete ex- pression of the rule would take into account these cases;

and if the present formulation does not do so, it has to be fixed accordingly. But would a complete expression of the rule also tell us what to do in cases where e.g. our laws of nature or our way of life changed radically (these changes are, after all, theoretically possible)? What counts as a sig- nature if every time one touched a paper with a pen the paper would catch fire? Or if pens and papers disappeared from our culture altogether?

The point here is not to invent more and more bizarre circumstances after each new formulation of the rule, nor to point out some fundamental defect in human cognitive ca- pacities (namely, the defect of not being able to know what the future will be like). The point is simply to remind us of the fact that

It is only in normal cases that the use of the word is clearly prescribed; we know, we are in no doubt, what to say in this or that case. The more abnormal the case, the more doubtful it becomes what we are to say. And if things were quite different from what they actually are […] – this would make our normal language-games lose their point. (PI 142)

Thus, we could say that a rule such as ‘A will is invalid unless signed by three witnesses’ is complete if it fulfils its purpose in ordinary circumstances – in the everyday legal practice, with the users of the rule having received a similar legal training, with people in general behaving as they usu- ally do, etc. (cf. PI 87) If things were quite different from what they are, we would not know how to apply this rule. This should not be understood as an empirical explanation of how rule-following is possible, but as a grammatical truth: it belongs to our concept of a rule that knowledge of its correct application presupposes ordinary circumstances. To want from rules more than this (which Dworkin seems to do) would, for Wittgenstein, to be a sign of having a confused conception of what rules are.

Perhaps Dworkin means, when he speaks of legal rules “dictating the result, come what may”, that the way they are intended determines the correct application. Thus, it would be the meaning of the rule which makes it determi- nate (in opposition to an indeterminate legal principle). This explanation seems to come to us naturally - to use Wittgen- stein’s example, if someone applies a simple arithmetical rule “+2” correctly up until 1000, but after that writes down 1004, 1008, etc., we most probably would react by saying to this person. “No, I didn’t mean that” or “Don’t you see what I mean?” (see PI 185) It is tempting here to assume that if this person just saw into the mind of the rule-giver, he would know how to continue the series correctly. But then one must also assume that at the instant of giving the rule “+2”, all the future applications are somehow present in that in- stant. As Wittgenstein puts it,

your idea was that that act of meaning the order had in its own way already traversed all those steps: that when you meant it your mind as it were flew ahead and took all the steps before you physically arrived at this or that one. (PI 188)

Just such an idea seems to lie behind Dworkin’s conception of legal rules. However, Wittgenstein continues by saying

that “you have no model of this superlative fact, but you are seduced into using a super-expression. (It might be called a philosophical superlative.)” (PI 192) And I think that when Dworkin defines legal rules as something which can in prin- ciple anticipate all the exceptions to them (if the rules are completely expressed), he in fact has no clear model of what he wants. He is seduced into using a super-expression be- cause he wants to make a rigid distinction between two dif- ferent types of legal standards; and, perhaps, because he is misled by the feeling we often have when we follow simple (legal) rules. Wittgenstein admits that it often strikes us as if

“the rule, once stamped with a particular meaning, trac[ed]

the lines along which it is to be followed through the whole of space” (PI 219). This image (as Martin Stone has pointed out) can, of course, be used as stating an everyday feature of our rules: surely rule-following sometimes is like tracing a line that the rule has drawn through the whole of space. It is only if one takes this to be an explanation of how rule- following is possible, or as giving us the essence of rules (as distinct from other standards) that it falls apart. (See Stone 2004, 276) For if it is taken as an explanation, then not even a basic arithmetical order can fulfil its requirements: the or- der “add two” does not in an absolute sense determine just one way of applying it.

4. Conclusion

The upshot of the preceding discussion is that in so far as Dworkin implies that legal rules are inherently, i.e. on the basis of their inner nature, different from legal principles, then the distinction between rules and principles is not sus- tainable. The idea of rules as absolutely determinate stan- dards which dictate a result in all circumstances is just a

“philosophical superlative” of which we have no actual model. However, if one wants to make a distinction between different types of legal standards by pointing out that they have different uses in the legal practice, this can justify the distinction. And, to be fair to Dworkin, he also uses this crite- ria in his separation of rules from principles; as we saw at the beginning of the paper, he talks e.g. of lawyers’ making

“use of standards that do not function as rules, but operate differently as principles…” (Dworkin 1977, 22, e.a.) The functional difference between rules and principles that Dworkin describes seems to boil down to this: if a judge refuses to apply a standard to a given case, and the rest of the legal community thinks that this is wrong, that the judge should have applied this standard, that it is always applied in cases like this, then the standard in question can be called a rule. If a judge can ignore a standard without this reaction, then it is a principle. My purpose here has not been to deny that such a distinction is possible; the purpose has only been to show, with the help of Wittgenstein, that if one turns this practical distinction into a metaphysical one, the result is just confusion. And I think that Dworkin’s way of characterising legal rules invites this confusion.

Literature

Dowrkin, Ronald 1977 “The Model of Rules”, in Taking Rights Seriously, London: Duckworth, 14-45.

Hart, H.L.A 1994 The Concept of Law (Second Edition with a Post- script), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stone, Martin 2004 “Focusing the Law: What Legal Interpretation is Not”, in Dennis Patterson (ed), Wittgenstein and Law, Aldershot:

Ashgate, 259-324.

Tushnet, Mark 1983 “Following the Rules Laid Down: A Critique of Interpretivisim and Neutral Principles” 96 Harvard Law Review, 781-827.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig 1953 Philosophical Investigations, Oxford:

Blackwell.

Against Expressionism: Wittgenstein, Searle, and Semantic Content

Brandon Absher, Lexington, KY, USA

brandon.absher@gmail.com

Introduction

In this paper, I present Wittgenstein’s criticisms of a group of popular theories, which I call “expressionism.” Expres- sionist theories of meaning claim that means of represen- tation (e.g. sounds) represent semantic content by virtue of their relation to mental states. Wittgenstein, however, pre- sents strong criticisms of such a theory. As an example of an expressionist theory of language, I will focus on the work of John Searle. Searle explicitly argues for a sophisti- cated version of expressionism that does not rely on phe- nomenal mental rules. Nevertheless, Searle’s theory suc- cumbs to Wittgenstein’s criticism.

1. Searle and Expressionism

According to Searle, a speaker typically has two intentions in performing a linguistic act: 1) a meaning intention and 2) a communicative intention (Searle 165-166, 1983). Searle holds that meaning intentions are prior to communicative intentions in the sense that a person must represent the world in some fashion if she is to communicate that repre- sentation. Indeed, a person may intend to perform a mean- ingful linguistic act without intending to communicate with an interlocutor. A person cannot, by contrast, intend to communicate with an interlocutor without intending to per- form a meaningful linguistic act. For example, a person can intend that her vocal performance be an utterance of the statement “Property is theft” even in a case where she does not address herself to an interlocutor. She cannot, on the other hand, intend to communicate with an interlocutor without intending that her vocal performance mean some- thing – that it be, for example, an illocutionary act like the utterance of “Property is theft.” As Searle sees it, a linguis- tic act is performed communicatively if and only if a speaker intends that an interlocutor recognize the per- formance of the action as a particular illocutionary act (Searle 168, 1983).

Searle’s notion of a meaning intention is at the heart of his semantic theory. A speaker’s meaning intention is her intention that a means of representation (R) represent some content (C). For Searle, this intention makes the difference between the production of meaningless physical facts and the performance of a meaningful linguistic act.

Sounds and marks become representations when a per- son utters or scribbles them with the intention that they have conditions of satisfaction (Searle 164, 1983). The conditions of satisfaction for some linguistic act are the states of affairs that must obtain or come about in order for it to be satisfied. For instance, if a person makes the statement “The war in Iraq is a moral and political disas- ter,” the conditions of satisfaction for this statement are that the war in Iraq is a moral and political disaster. A lin- guistic act is meaningful in that it is performed with the intention that it specify a possible state of the world that will satisfy it.

According to Searle, linguistic acts derive their meaning from Intentional mental states. Intentional mental states, on the other hand, are directly and inherently re- lated to their conditions of satisfaction. Nothing further is required to establish this link (Searle vii, 1983). The syn-

tactic or formal properties of the state are irrelevant to whether it specifies particular conditions of satisfaction (Searle 12, 1983). For example, a belief that there is life on Mars is different from a belief that neo-liberal economic policies impoverish much of the world because they are true under different circumstances. For Searle, linguistic acts derive their capacity to represent the world from the direct and inherent relation of Intentional mental states to the world.

2. The Paradox: Meaning and Rules

Throughout his later work, Wittgenstein gives examples of mental rules with the intention of showing that means of representation cannot be linked to represented contents by such rules. In the Philosophical Investigations, he consid- ers several kinds of mental rule which might be thought to effect such a connection. He writes, for instance,

When someone defines the names of colours for me by pointing to samples and saying "This colour is called 'blue', this 'green'..." this case can be compared in many respects to putting a table in my hands, with the words written under the colour-samples… One is now inclined to extend the comparison: to have understood the definition means to have in one's mind an idea of the thing defined, and that is a sample or picture. So if I am shewn various different leaves and told "This is called a 'leaf'", I get an idea of the shape of a leaf, a picture of it in my mind. (PI, §173)

Wittgenstein levels two basic objections at such attempts to link means of representation to represented contents: 1) a mental rule can offer no more guidance in acting than does a physical rule and 2) with respect to a mental rule there is no distinction between being guided by or obeying the rule and merely seeming to be guided by or obey the rule.

To establish the first point, Wittgenstein shows that a mental rule is no better than a physical rule in that it can be used differently. He writes,

Well suppose that a picture does come before your mind when you hear the word “cube”, say the drawing of a cube. In what sense can this picture fit or fail to fit a use of the word “cube”? – Perhaps you say: “It’s quite sim- ple; - if that picture occurs to me and I point to a triangu- lar prism for instance, and say it is a cube, then this use of the word doesn’t actually fit the picture.” – But doesn’t it fit? I have purposefully so chosen the example that it is quite easy to imagine a method of projection according to which the picture does fit after all. (PI, §139)

The possession of a mental rule cannot be the bridge link- ing a means of representation (R) to some content (C) since even a mental rule must be understood or meant in some way. A diagram illustrating parallel parking, for in- stance, may be understood accidentally or deliberately as a diagram illustrating how to pull out from a parking spot along the street. Simply bringing such a diagram to mind, then, when given an order to park along the street (say at a licensing exam) cannot amount to understanding the order. (PI, §140)

Against Expressionism: Wittgenstein, Searle, and Semantic Content / Brandon Absher

To establish the second point, Wittgenstein stresses what is today called the “normative” character of rules (Kripke 37, 1982). A rule prescribes how things ought to be done under certain circumstances and serves the pur- poses of guidance, instruction, and justification for this reason. Mental rules, however, lack this quality. Wittgen- stein explains

Let us imagine a table (something like a dictionary) that exists only in our imagination. A dictionary can be used to justify the translation of a word X by a word Y. But are we also to call it a justification if such a table is to be looked up only in the imagination? – “Well, yes; then it is a subjective justification.” – But justification consists in appealing to something independent. – “But surely I can appeal from one memory to another. For example, I don’t know if I have remembered the time of departure of a train right and to check it I call to mind how a page of the time-table looked. Isn’t it the same here?” – No; for this process has got to produce a memory which is ac- tually correct. If the mental image of the time-table could not itself be tested for correctness, how could it confirm the correctness of the first memory? (PI, §265)

Since a mental rule is private, there is no standard by which to judge whether it is followed other than that it seems to be so to the person who possesses it. The dis- tinction between what the rule actually prescribes and what it seems to prescribe thereby collapses.

3. A Rejoinder

It may seem that these arguments do not apply to the kind of expressionism offered by Searle. Whereas Wittgenstein is concerned in these passages with a theory that links means of representation to their represented contents using mental rules, Searle’s theory links means of representation to their represented contents via Intentional mental states. These states are not specters in the phenomenal theater of the mind like the tables Wittgenstein considers. Searle argues that these states are related directly and inherently to their conditions of satisfaction. As he explains,

A belief is intrinsically a representation in this sense: it simply consists in an Intentional content and a psycho- logical mode… It does not require some outside Intention- ality in order to become a representation, because if it is a belief it already intrinsically is a representation. Nor does it require some nonintentional entity, some formal or syntac- tical object, associated with the belief which the agent uses to produce the belief (Searle 22, 1983).

Linguistic acts, conversely, are indirectly linked to their con- ditions of satisfaction in virtue of this direct relation.

It is doubtful that Wittgenstein would view this position as an improvement on a theory according to which mental rules are this link. In the Blue Book he writes,

Now we might say that whenever we give someone an order by showing him an arrow, and don't do it 'mechani- cally' (without thinking), we mean the arrow in one way or another. And this process of meaning, of whatever kind it may be, can be represented by another arrow (pointing in the same direction or the opposite of the first). In this pic- ture of 'meaning and saying' it is essential that we should imagine the processes of saying and meaning to take place in two different spheres. Is it then correct to say that no arrow could be the meaning, as every arrow could be meant the opposite way? (BB, 33-34)

According to Searle, meaningless physical facts become meaningful representations by being related to Intentional

mental states. As he writes, “Entities which are not intrinsi- cally Intentional can be made Intentional by, so to speak, intentionally decreeing them to be so” (Searle 175, 1983).

An arrow, for instance, is an instruction because someone so intends it. However, according to Wittgenstein, this “de- cree” that some means of representation represent some- thing relies on a means of representation. Thus, one can think of it as a mental arrow or a mental sentence like

“Means of representation (R) represents content (C)” ac- companying the other, external means of representation.

But, of course, such mental representations fall prey to Witt- genstein’s criticisms of mental rules.

Searle might argue in response that Intentional men- tal states are inherently related to their contents. There is no such thing as “using an Intentional state differently,” since the relationship between the state and the content it repre- sents is inherent in the state itself (Searle 22, 1983). In op- position to this Wittgenstein writes,

What one wishes to say is: “Every sign is capable of inter- pretation; but the meaning mustn’t be capable of interpre- tation. It is the last interpretation.” Now I assume that you take the meaning to be a process accompanying the say- ing, and that it is translatable into, and so far equivalent to a further sign. You have therefore further to tell me what you take to be the distinguishing mark between a sign and the meaning. If you do so, e.g., by saying that the mean- ing is the arrow which you imagine as opposed to any which you may draw or produce in any other way, you thereby say that you will call no further arrow an interpre- tation of the one which you have imagined. (BB, 34) Intentional mental states are themselves embodied in means of representation and to claim of these that they are inherently related to their content is to decide that they can- not be used differently, not to discover this fact.

In fact, Searle argues for the importance of a back- ground of dispositions, abilities, etc. on the basis of consid- erations similar to these. He writes,

Suppose you wrote down on a huge roll of paper all of the things you believed. Suppose you included all of those be- liefs which are, in effect, axioms that enable you to gener- ate further beliefs, and you wrote down any ‘principles of inference’ you might need to enable you to derive further beliefs from your prior beliefs… About this list I want to say, if all we have is a verbal expression of the content of your beliefs, then so far we have no Intentionality at all.

And this is not because what you have written down are

‘lifeless’ marks, without significance, but because even if we construe them as Fregean semantic entities, i.e., as propositional contents, the propositions are not self- applying (Searle 153, 1983).

To have an Intentional mental state is to be able to “apply” it – i.e. to be able to discern the conditions that satisfy it. This requires a background of dispositions, abilities, etc. But, for Searle this background is a mental structure (Searle 153- 154, 1983). One might have such dispositions, abilities, etc.

even if one were a brain in a vat. But, to link means of repre- sentation to their represented contents in this manner denies that there is an independent standard according to which they could be said to represent one state of affairs rather than another (Kripke 22-37, 1982). One’s Intentional mental states thus represent whatever they seem to represent. But, people are often inclined to their count beliefs true when they are manifestly false. A belief’s truth-conditions are in- dependent, that is, of anyone’s inclination to count it true.

Against Expressionism: Wittgenstein, Searle, and Semantic Content / Brandon Absher

Conclusion

In this paper I have presented Wittgenstein’s criticisms of Searle’s expressionist semantics. Expressionist theories of meaning hold that means of representation (e.g. sounds) are linked to their represented contents by virtue of their relation to mental states. This way of thinking about lan- guage presupposes that means of representation are fun- damentally meaningless; that they are dead and must be animated by the mind. This picture of meaning, however, is beset by paradox and disquiet. Wittgenstein does not seek to link dead means of representation to semantic content.

Rather, he shows that in people’s everyday experience language is already alive. In general, people experience representations, not meaningless means of representation.

Literature

Kripke, Saul 1982 Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language: An Elementary Exposition, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Searle, John 1983 Intentionality: An Essay in the Philosophy of Mind, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig 2001 Philosophical Investigations, G. E. M.

Anscombe (trans.), Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig 1958 The Blue and the Brown Books: Pre- liminary Studies for the Philosophical Investigations, New York:

Harper Torchbooks.