Technical Report 2019

20 .19

www.bifie.at

Testing Writing for the E8 Standards Technical Report 2019

BIFIE Salzburg (Hrsg.), Salzburg, 2019.

The Technical Report 2019 has been adapted from the Technical Report 2011:

Otmar Gassner Claudia Mewald Rainer Brock Fiona Lackenbauer Klaus Siller

Der Text sowie die Aufgabenbeispiele können für Zwecke des Unterrichts in österreichischen Schulen sowie von den Pädago gischen Hochschulen und Universitäten im Bereich der Lehrer aus-, Lehrerfort- und Lehrerweiterbildung in dem für die jeweilige Lehrveranstaltung erforderlichen Umfang von der Homepage (www.bifie.at) heruntergeladen, kopiert und verbreitet werden. Ebenso ist die Vervielfältigung der Texte und Aufgabenbeispiele auf einem anderen Träger als Papier (z. B. im Rahmen von Power-Point-Präsentationen) für Zwecke des Unterrichts gestattet.

Autorinnen und Autoren:

Klaus Siller Fiona Lackenbauer Armin Berger Rebecca Sickinger Andrea Kulmhofer-Bommer

3 1 Introduction

3 1.1 Objectives and Structure of the Report

5 2 Writing to Communicate (Cognitive Validity)

6 3 The E8 Writing Test Construct (Context Validity) 6 3.1 Purpose of the Test

6 3.2 Description of Test Takers 6 3.3 Test Level

7 3.4 The E8 Writing Test Construct Space 9 3.5 E8 Writing Tasks

10 4 Rating (Scoring Validity) 11 4.1 Rating Scale Interpretation 11 4.1.1 Performances at Band Zero

11 4.1.2 Scale Interpretation – Task Achievement 13 4.1.3 Scale Interpretation – Cohesion and Coherence 15 4.1.4 Scale Interpretation – Grammar

18 4.1.5 Scale Interpretation – Vocabulary 20 4.2 Rater Training and the Rating Process 20 4.2.1 Rater Training

20 4.2.2 The Rating Process

20 5 Test Administration in 2019 21 6 Reporting and Feedback 21 7 Bibliography

22 8 Appendices

1. Introduction

This report details the writing section of the National Educational Standards Test English, year 8 (Bildungsstan- dardüberprüfung Englisch, 8. Schulstufe; E8). The Writing Test is the final part of the E8 Test, which comprises listening, reading, and writing.

In the Austrian English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teaching context, writing has always been an important element and considered a good predictor of pupils’ overall language ability. Thus, writing is taught from year one of secondary education on a regular basis, supported with guided writing tasks in approved text books. When it comes to assessing writing, the focus was generally on grammar and vocabulary skills. The E8 Writing rationale was to broaden the approach to the teaching, testing, and marking of writing (Gassner, Mewald & Sigott, 2008;

Gassner, Mewald, Brock, Lackenbauer & Siller, 2011; Kulmhofer & Siller, 2018). Consequently, the Austrian ministry of education implemented an external assessment of writing in the context of the E8 standards assess- ment to encourage change in the Austrian EFL classroom at lower secondary level. The developments from the initial baseline testing up to the first nationwide assessment of writing (E8 Writing Test) are described in the first and second editions of the technical report “Testing Writing for the E8 Standards” (Gassner et al. 2008; Gassner et al. 2011). This report discusses the changes and adaptations that were necessary for the second administration of the E8 Writing Test in April 2019.

1.1. Objectives and Structure of the Report

The aim of the Technical Report 2019 is to provide a brief theoretical background to writing and the assessment of writing in the E8 context. It is hoped that teachers will use the information in this report and additional material on the BIFIE website in their classrooms and so contribute to a positive washback of the assessment process.

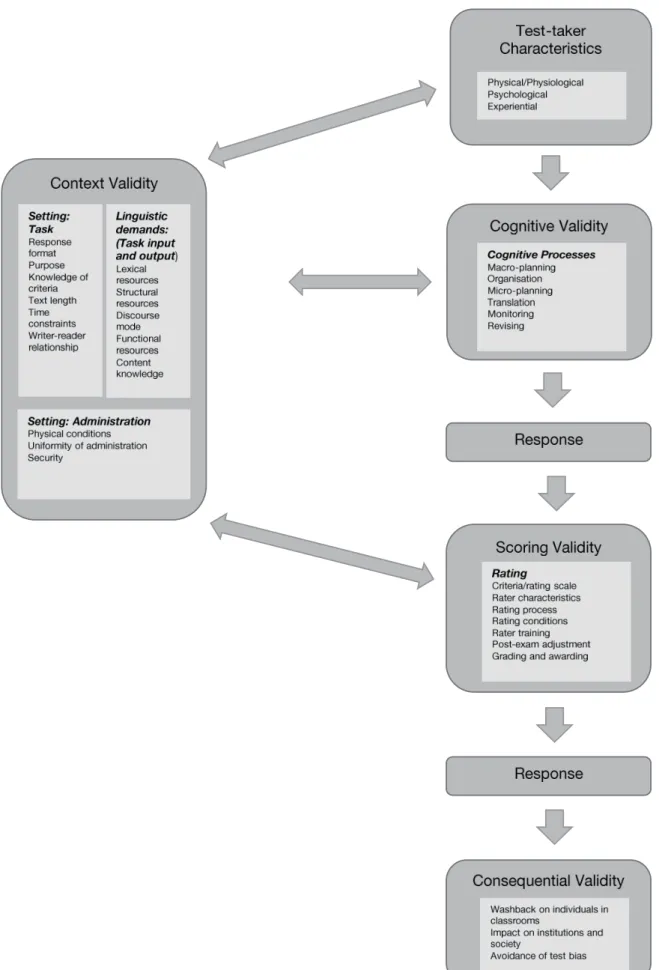

The structure of the report reflects Shaw and Weir’s (2007) conceptualisation of writing assessment (Figure 1) by looking at different aspects of validity and describing how they were taken into consideration by the E8 test developers prior to the test, during test development phases, and after the test. Test-taker characteristics and cognitive validity are only addressed briefly in this report, as these remained stable over the administration cycles of the test. More detailed information on test-taker characteristics and cognitive validity can be found in the Technical Report 2011 (Gassner et al., pp. 3–8).

Section 2 considers cognitive validity and describes the cognitive model of writing that underpins the E8 Writing Test. Context validity (including test purpose, test takers, test level, and test construct) is dealt with in section 3.

Information about the rating process (scoring validity) is provided in section 4, discussing the rating criteria, the latest version of the E8 Writing Rating Scale, the rater training, and the rating process. Finally, sections 5 and 6 report on how the E8 Writing Test was administered in 2019 and how test results were communicated.

Figure 1: Conceptualizing writing performances (adapted from Shaw & Weir, 2007, p. 4)

2. Writing to Communicate (Cognitive Validity)

The E8 Writing Test was influenced by Hayes and Flower’s (1980), Grabe and Kaplan’s (1996), and Field’s (2004) cognitive models of writing. These models describe writing as a set of processes such as planning, organising and goal setting, translating thoughts into text, and editing. From this perspective, the E8 Writing Test expects candidates to engage in processes of planning, writing, and editing a text. These processes should be related to the levels of language proficiency targeted by the test. Bereiter and Scardamalia (1987) note two strategies that differentiate between skilled and less skilled writers: knowledge telling and knowledge transformation. Know- ledge telling is commonly understood as “generating content from within remembered linguistic resources in line with task, topic, or genre” (Shaw & Weir, 2007, p. 43) and thus is typical of less skilled writers. More skilled writers “adjust, shape, and revise … as they write to conform to their goals, audience concerns, knowledge of text and language conventions, and evaluations of text produced thus far” (Cumming, 2015, p. 70), reflecting a knowledge transformation strategy.

Alongside the cognitive models of writing, the communicative language competences as set out in the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) strongly influenced the E8 Writing Test. Communicative language competence is divided into three components (Council of Europe 2001, p. 108):

Linguistic competence

Sociolinguistic competence

Pragmatic competence

Linguistic competence refers to the users’ knowledge of and their ability to use the rule system of a language in order to produce meaningful language orally or in writing. This knowledge includes lexical, grammatical, semantic, phonological, orthographic, and orthoepic competences (the competence to read texts out loud).

Sociolinguistic competence includes knowledge of linguistic markers of social relations including politeness conventions and register differences, which are needed, in particular, for face-to-face interactions and written correspondence. Sociolinguistic competence thus allows the writer to choose the appropriate phrase and tone of voice for the situation.

Pragmatic competence involves the functional use of linguistic resources. It encompasses the knowledge needed to organise, structure, and arrange a message; to perform a communicative function; and to deal with inter- actional and transactional schemata.

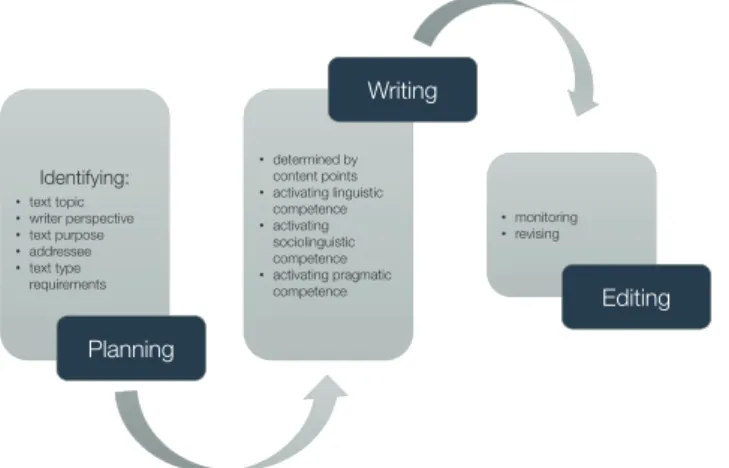

The E8 Writing Test synthesises the cognitive processes described above and the communicative language com- petences set out in the CEFR. This approach is illustrated in Figure 2. The E8 Writing Test model distinguishes between a truncated planning and editing phase, with a focus on the writing phase. The processing and linguistic demands posed upon the test takers in the E8 context mainly involve knowledge telling.

Figure 2: The E8 writing process (adapted from Gassner et al., 2008; Kulmhofer & Siller, 2018)

Identifying:

•text topic

•writer perspective

•text purpose

•addressee

•text type requirements

•determined by content points

•activating linguistic competence

•activating sociolinguistic competence

•activating pragmatic competence

•monitoring

•revising

Planning

Writing

Editing

Kulmhofer and Siller (2018) point out that the planning phase in the E8 context “is not elaborate or extensive”

(p. 133). Test takers have to identify text topic, writer perspective, text purpose, and addressee, alongside text- type requirements before beginning the writing phase.

In the actual writing phase, aspects of organisation, content, and language have to be considered. Content points pre-structure the content that is to be included in the text, thus reducing the cognitive load for test takers.

Linguistic, sociolinguistic, and pragmatic competences will have to be activated when producing the text.

The final phase includes monitoring and revising activities, which might happen simultaneously with the writing phase. In the E8 process, this phase might involve “adding, deleting or modifying a content point, adding cohesive devices, replacing poor words and phrases with better ones, or simply correcting mistakes in spelling and structure” (Gassner et al. 2008, p. 10).

3. The E8 Writing Test Construct (Context Validity)

3.1. Purpose of the Test

The main purpose of the writing test is to assess test takers’ writing ability at the end of year 8 (the fourth year of lower secondary English language instruction). Information from the E8 testing is used both for system monitoring and the improvement of classroom procedures. Individual test results can be accessed by the test takers.

3.2. Description of Test Takers

The test takers are pupils in the two different types of lower secondary schools (APS & AHS), towards the end of year 8 (8. Schulstufe). The majority of test takers will be aged 14. Those pupils who are not being taught English as part of the official curriculum in the 8th school year, for example pupils with special education needs, are exempted from doing the tests.

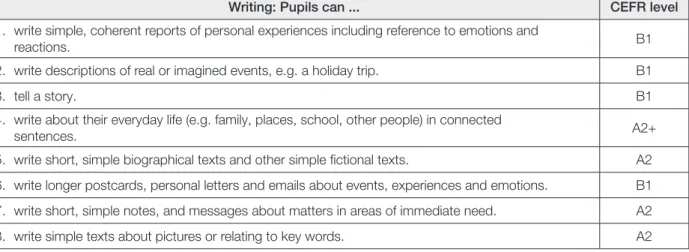

3.3. Test Level

The test targets levels A2 to B1 in the CEFR, which are the prescribed levels after four years of learning English at lower secondary school as stipulated in the Austrian National Curriculum for Foreign Languages (https://

bildung.bmbwf.gv.at/schulen/unterricht/lp/ahs8_782.pdf?61ebzr). The national educational standards also reflect this attainment target (Table 1).

Writing: Pupils can ... CEFR level

1. write simple, coherent reports of personal experiences including reference to emotions and

reactions. B1

2. write descriptions of real or imagined events, e.g. a holiday trip. B1

3. tell a story. B1

4. write about their everyday life (e.g. family, places, school, other people) in connected

sentences. A2+

5. write short, simple biographical texts and other simple fictional texts. A2 6. write longer postcards, personal letters and emails about events, experiences and emotions. B1 7. write short, simple notes, and messages about matters in areas of immediate need. A2

8. write simple texts about pictures or relating to key words. A2

Table 1: National educational standards can-do descriptors for writing (adapted from Kulmhofer & Siller 2018, p. 135/36)

These can-do descriptors, based on the CEFR and the Austrian National Curriculum for Foreign Languages, not only inform E8 test development but should also guide classroom instruction.

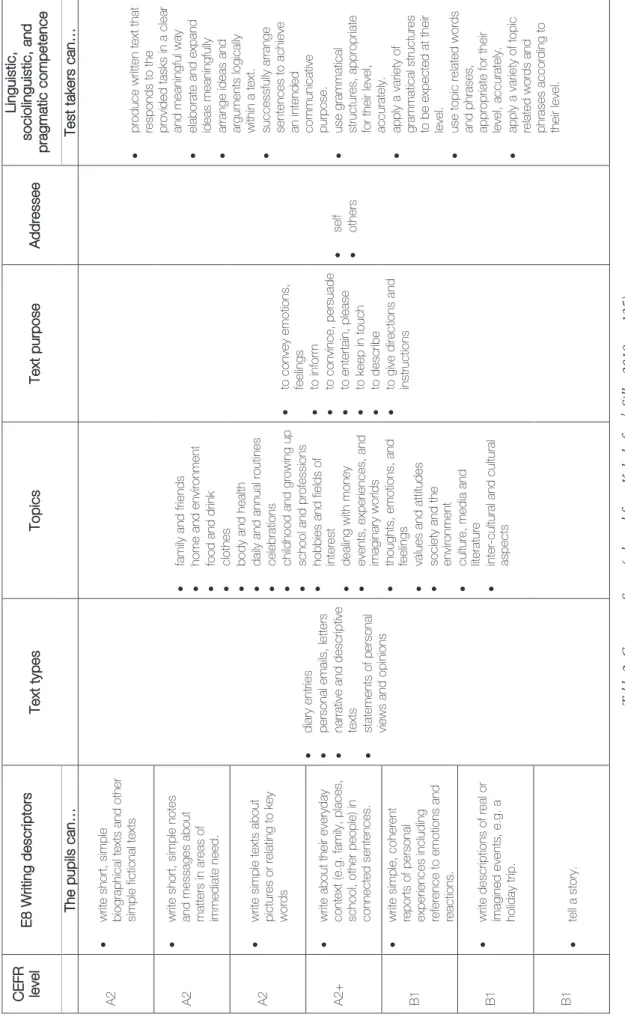

3.4. The E8 Writing Test Construct Space

The following table summarises the construct space relevant for item and test design. It shows the levels that the test is targetting, ranging from A2 to B1; the can-do descriptors as specified in the relevant legal document (BIST-Verordnung); text types; topic areas; the text purpose; addressees; and the linguistic, sociolinguistic, and pragmatic competences.

Topics are restricted to areas that can safely be assumed to be familiar to the test takers as they are set down in the Austrian curriculum. The linguistic, sociolinguistic, and pragmatic competences, as shown in the final column of the table, are reflected in the assessment criteria of the E8 Writing Rating Scale (see section 4).

Table 2: Construct Space (adapted from Kulmhofer & Siller 2018, p. 135)

CEFR level E8 Writing descriptors Text typesTopics Text purpose Addressee

Linguistic, sociolinguistic, and pragmatic competence The pupils can…Test takers can… A2 write short, simple biographical texts and other simple fictional texts diary entries personal emails, letters narrative and descriptive texts statements of personal views and opinions

•family and friends •home and environment •food and drink •clothes •body and health •daily and annual routines •celebrations •childhood and growing up •school and professions •

hobbies and fields of interest

•dealing with money •events, experiences, and imaginary worlds •

thoughts, emotions, and feelings

•values and attitudes •society and the environment •

culture, media and literature

•inter-cultural and cultural aspects

to convey emotions, feelings to inform to convince, persuade to entertain, please to keep in touch to describe to give directions and instructions

self others

produce written text that responds to the

provided tasks in a clear and

meaningful way elaborate and expand ideas meaningfully arrange ideas and arguments logically within a text.

successfully arrange sentences t

o achieve

an intended communicative purpo

se.

use grammatical structur

es, appropriate for their level, accurately. apply a variety of grammatical structures to be expected at their level. use topic related words

and phrases, appropriate for their level, accurately.

apply a variety of topic related wo

rds and phrases according to their level.

A2 write short, simple notes

and messages about matters in areas

of immediate need. A2 write simple texts about pictures or relating to key words A2+ write about their everyday context (e.g. family, places, school, other people) in connected sentences. B1

write simple, coherent reports of

personal experiences including reference to emotions and reactions. B1write descriptions of real or imagined events, e.g. a holiday trip. B1 tell a story.

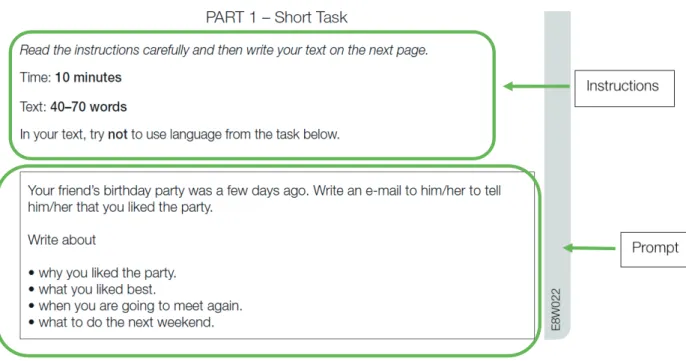

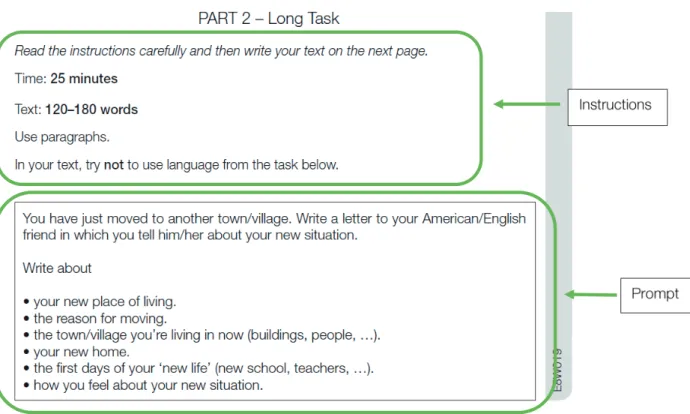

3.5. E8 Writing Tasks

E8 writing tasks are designed to elicit responses from A2 to B1 that reflect the construct as defined in the con- struct space. The E8 Writing Test consists of two individual tasks: the short task and the long task.

Each task comprises instructions and a prompt. They are both at a language level no higher than A2. The instructions stipulate that the short task has an expected word count of 40 to 70 words within a time limit of 10 minutes, while the long task has an expected word count of 120 to 180 words within a time limit of 25 minutes.

Additionally, pupils are informed that they should avoid using language given in the prompt whenever possible.

However, it is important to note here that at this early stage of language learning, there are individual words and phrases that pupils might need to copy from the prompt as their language repertoire lacks alternatives.

The prompts are appropriate for the age of the test takers and free of stereotypes. Although the prompts offer the opportunity to write from experience, they are designed not to intrude upon the pupils’ personal feelings.

Prompts state the reason for writing, the intended audience, and the required text type. This contextualisation is no longer than a maximum of 50 words (excluding content points). The short task has four content points and the long task has six content points. Content points stipulate the expected content of the test takers’ responses and provide structural guidance.

Below are labelled examples of tasks.

Figure 3: Exemplar short task

Figure 4: Exemplar long task

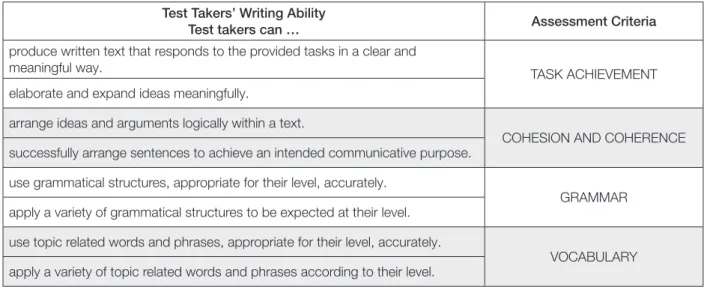

4. Rating (Scoring Validity)

The test is designed to elicit language performances that are assessed in four dimensions: Task Achievement (TA), Coherence & Cohesion (CC), Grammar (G), and Vocabulary (V). Task Achievement is demonstrated by an appropriate response to the task. In practical terms, this means all expected content points of the prompt are to be clearly and meaningfully mentioned by the test takers, and for the higher bands, elaboration of some content points is required. In all instances, text type conventions and minimum word counts should be met.

The second dimension is the ability to produce fluent texts by using adequate devices to create coherence and cohesion on sentence, paragraph, and text level. Indicating paragraphs is mandatory in long texts for perfor- mances at band 3 and above. Ideally, a new paragraph is signalled by indenting or leaving a blank line.

The third dimension refers to the range and accuracy of the grammatical structures. The fourth dimension refers to the range, accuracy, and relevance of the vocabulary used.

The two tasks are assessed separately by trained raters, using an analytic rating scale based on these four dimensions. Multiple-rating and double-rating of a sufficiently large sample of scripts help to ensure reliability.

Differences in rater severity are adjusted for through multi-faceted Rasch analysis.

The following table depicts the four dimensions of the analytic rating scale for writing.

Test Takers’ Writing Ability

Test takers can … Assessment Criteria

produce written text that responds to the provided tasks in a clear and

meaningful way. TASK ACHIEVEMENT

elaborate and expand ideas meaningfully.

arrange ideas and arguments logically within a text.

COHESION AND COHERENCE successfully arrange sentences to achieve an intended communicative purpose.

use grammatical structures, appropriate for their level, accurately.

GRAMMAR apply a variety of grammatical structures to be expected at their level.

use topic related words and phrases, appropriate for their level, accurately.

VOCABULARY apply a variety of topic related words and phrases according to their level.

Table 3: Test takers’ writing ability and the four areas of assessment (taken from Kulmhofer & Siller 2018, p. 143) The subsequent section describes and explains these four dimensions in greater depth. A copy of the most recent version of the E8 Writing Rating Scale can be found in the appendices.

4.1. Rating Scale Interpretation

While the 2011 version of this report addresses the development of rating scales in detail, this edition focuses on how to read and interpret the E8 Writing Rating Scale. The four dimensions are given equal weighting and thus are seen as equally important in the teaching and assessing/rating of writing skills.

4.1.1. Performances at Band Zero

Before beginning to rate a text, the rater needs to decide if the text meets the criteria for rating. In a number of cases, there is no assessment in any of the four dimensions. If the rater finds that the text meets one (or more) of the criteria below, the text is marked as zero in all four dimensions and rating is judged to be complete.

Texts that have not even been attempted, i.e. an empty page

Texts that are illegible, mainly in German, or just drawings

Fewer than 60 words in long texts and fewer than 20 words in short texts

Texts that do not deal with the given topic and the content points listed

Texts that cover fewer content points than necessary for band 1 in TA (see below)

Texts that are extremely rude, sexist, racist, or propagating violence

As the information on what disqualified a particular performance is essential in the monitoring process, the raters will mark their decision in BIFIE’s electronic coding and rating platform (CORA), showing which criterion has necessitated the awarding of zero in all dimensions. Whereas the first five points need only a click by the rater, the last one requires a brief justification to make this judgement transparent.

4.1.2. Scale Interpretation – Task Achievement

The scale on Task Achievement (TA) has no direct link to the CEFR and assesses the content components of a text and text type requirements.

i. Content

Having ascertained that the response meets the criteria for rating, raters have to decide whether a content point has been clearly and meaningfully mentioned. When assessing Task Achievement, the first question is how many content points have been addressed (the quantitative component of the dimension), and then the second

question is how well each point has been elaborated (the qualitative component). For a content point to be seen as meaningfully mentioned, one clear, understandable idea addressing the content point needs to be expressed.

Sometimes, key words from the prompt appear in the text, but the language around them does not make sense.

This would not be considered as a content point being clearly and meaningfully mentioned.

Once a content point has been assessed as mentioned, the next issue to decide is whether it has been elaborated.

Elaboration is defined as new information or detailed description being added to a content point. For a short task, the rater can award excellent, good, and/or weak elaboration, while for a long task good and/or weak elaboration can be recognised.

For example, in a response to the long prompt below

the following example can serve to demonstrate what mentioning a content point means:

We live now in New York near the Central Park, we moved because my mum had not found a job.

In this sentence, content points 1 and 2 are mentioned. The text goes on:

But in New York my mum has a good job.

This second sentence extends content point 2, but as it is little more than a reformulation of the previous sentence, it is not elaboration.

An example of weak elaboration can be seen in the following example answering content point 5:

I have new friends but you are forever my best friend. The new school is very big. The teachers are sometimes unfriendly. And the school colleagues are not polite.

The first sentence mentions new and old friends. Then the response moves abruptly to the cues from the prompt and adds some simple words to each. Finally, there is a new sentence based on the same pattern. There is some elaboration here, but it is fairly simplistic. This would be assessed as weak elaboration.

Good elaboration involves the introduction of a new idea, a real extension of what has been said before. Examples of good elaboration for content point 1 would be:

In New York she works as a secretary in a bank on the 35th floor of a high building in Manhattan and is quite happy.

or:

In New York she sells pancakes in the streets, and she is happy.

There is more room for elaboration in a long prompt response than in a short one. Therefore, raters should be aware that elaboration in a short prompt will not be as extensive as similarly graded elaboration in a long prompt. To recognise that elaboration is more challenging in a short text, an additional level of ‘excellent’

elaboration has been added to reward instances where considerable detail or information has been included.

To accommodate the occasional difficulty of extensive text in a written response that is not obviously related to a content point, test takers can be rewarded for showing prompt-related elaboration. This can be defined as elaboration that is general though meaningful and clearly related to the task but cannot be linked to an individual content point despite obviously adding extra information to the written response. Prompt-related elaboration is classified in the same manner as content point elaboration and should be judged to be excellent, good, or weak.

The Task Achievement grids have been designed to assist in this process and although they cannot list every eventuality, they supplement the E8 Writing Assessment Scale with a grid each for short and long prompts.

If the text responding to the prompt is not good enough to gain a band one in Task Achievement, then a band zero must be given and the text would then be zero rated in all four dimensions.

ii. Text type requirements

In the E8 Writing Test, test takers are asked to write in an informal style, and they need to know how to open and close a letter or an email as both require some kind of salutation and closing formula. The meeting of text type requirements is mandatory, and texts are downgraded by one band if text type requirements have not been met (missing/inappropriate salutation or closing formula). Texts that are placed at band zero due to down- grading (text type requirements) are assessed in the other three dimensions.

iii. Text length

Texts that are significantly below the required number of words (fewer than 60 words for a long prompt and 20 words for a short prompt) are rated zero in all dimensions. This is due to insufficient text to adequately assess the other three dimensions.

4.1.3. Scale Interpretation – Cohesion and Coherence

Coherence refers to the logical arrangement of ideas and arguments within a text. In a coherent text, the writer successfully arranges his/her sentences to achieve a purpose, e.g. to reflect the chronological sequence of events or to develop a convincing line of argument. A coherent text makes it easy for the reader to follow the writer’s train of thought, so that there is no need to stop and reread in order to establish meaning as ideas and arguments flow smoothly and logically. A less coherent text, however, impairs readability and appears disconnected.

The term cohesion relates to the relationships between elements of a text, which is the way words, phrases, and individual sentences are linked. There are several ways in which cohesion can be established. One is reference through the use of pronouns (personal, possessive, demonstrative, etc.) and comparatives. At a very simple level, cohesion is realised by using the personal pronoun he in the following two sentences:

My best friend is Michael. He is in the same class as I.

Similarly, in the following example, the possessive mine refers to the room in the previous sentence, thus linking the two sentences in the passage:

My sister has the big room in the house. Mine is a lot smaller.

Demonstratives can serve the same purpose. For example, in the sentence below, the word that refers to the camera the writer got, thereby linking the two sentences successfully:

I got a new camera for my birthday. That was my best present ever.

Simple sentences can be connected by using conjunctions such as ‘and’, ‘but’ or ‘because’. For example:

My holiday was a disaster. It rained almost every day.

can be reformulated as

My holiday was a disaster, because it rained almost every day.

Another solution would be keeping two sentences but linking them by saying:

It rained almost every day. Therefore, my holiday was a disaster.

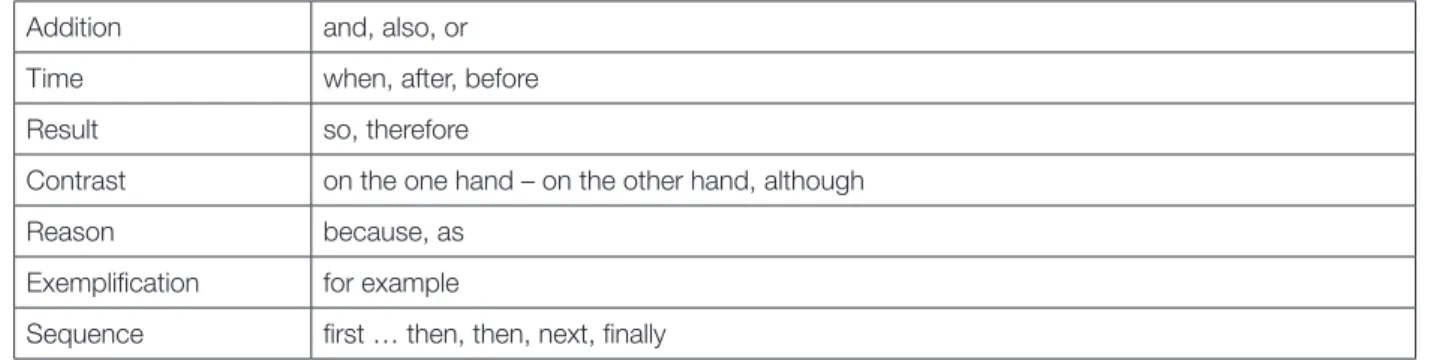

Examples of cohesive devices that writers might use at level A2/B1 are:

Addition and, also, or

Time when, after, before

Result so, therefore

Contrast on the one hand – on the other hand, although

Reason because, as

Exemplification for example

Sequence first … then, then, next, finally

Table 4: Examples of cohesive devices expected at CEFR level A2/B1

A text can be coherent even if very few of these cohesive devices are used. Conversely, the frequent use of cohesive devices does not necessarily turn an incoherent text into a coherent one. A particularly successful way of establishing cohesion in a text is the use of lexical chains. For example:

When I think of clothing I would say that T-shirts with crazy designs like dots, squares, skulls are definitely in. All my friends are wearing that and they think it’s the latest craze! This year wearing the ‘right’ shoes like ‘Converse’ or

‘Vans’ is very important. Everybody loves to wear them because it’s a must-have!

In the first sentence, the writer uses the phrase definitely in to describe certain kinds of fashionable T-shirts. In the following sentence, this idea is continued by using the phrase the latest craze. At the end of the paragraph, this concept of a fashion product is reformulated as it’s a must-have. This establishes a lexical chain that binds the sentences together and establishes a smooth flow of ideas in the paragraph.

Sentences can also be connected by substituting one or more words in a sentence. For example:

We have a lot of field trips in our school. The nicest one was to Schönbrunn Zoo.

Here the writer has replaced field trips with one. And in this example:

Girls are better at English. Everybody thinks so.

the word so represents the whole idea that girls are doing better at languages.

In the CEFR, coherence and cohesion are aspects of the pragmatic competences of a language user, alongside flexibility to circumstances and thematic development. The progression in the E8 scale for coherence and cohesion moves from the very basic skill of being able to link words with linear connectors such as ‘and’ or ‘then’ to successfully using connectors that express reason (‘because’) and contrast (‘but’) to link words or phrases. Moving up the scale, texts might show the ability to use these most frequent connectors to connect listed points, whereas one level further up the loosely connected list of points becomes a fully connected linear sequence of points.

The E8 Writing Rating Scale includes aspects of both coherence and cohesion. Texts at band 7 are expected to be clear and coherent in their message showing good sentence as well as paragraph level cohesion, making the text flow fairly well. The sentences should flow smoothly and logically to produce a coherent paragraph and might show relationships between paragraphs. A slightly less fluent text due to an attempt to navigate more complex relationships between ideas should not be penalised.

Texts at bands 5 are expected to be mostly clear and coherent in their message although some vagueness and ambiguity is possible. Longer stretches of connected language, in at least parts of the text, at paragraph level are expected.

Band 3 texts are characterized by frequently incoherent text elements, which may impair clarity and readability.

Sentences should be successfully linked using simple connectors resulting in a list of points rather than a longer connected sequence.

Band 1 texts are not coherent at all and consist of mostly disconnected chunks of language possibly only using the most basic linear connectors such as ‘and’ or ‘then’ as cohesive devices at word group level.

At bands 3–7, recognisable paragraphs are expected, and failure to show such paragraphs will result in down- grading of the text by one band. Ideally, such paragraphs are signalled by either indentation or a blank line.

However, if there is enough free space after a full stop in the previous line to accommodate the first word of the new sentence from the next line, this will also be accepted as an indication of paragraphing. Editing marks added later by the test taker to indicate paragraphing are acceptable. A sequence of one-sentence paragraphs cannot be accepted as successful paragraphing. Paragraphing is not mandatory in short texts. While most texts will follow the structure suggested by the content points in the prompt, this suggested order is not prescribed.

4.1.4. Scale Interpretation – Grammar

When assessing grammar, raters have to consider two aspects. Firstly, do the test takers have the necessary range of grammatical resources (i.e. grammatical structures) to accomplish the task, and secondly, can they apply these structures accurately?

i. The concept of grammatical range

Grammatical range refers to the variety of grammatical structures that test takers produce in their texts. The ability to show a variety is not only influenced by the test takers’ grammatical knowledge, but also by the design of the tasks. That is, short prompts (designed to elicit A2 language) provide fewer opportunities to show grammatical range than long prompts (designed to elicit B1 language), as the time allocation and the expected number of words will have an impact on range. Ideally, texts will show a varied range of structural features.

Nevertheless, variation should not be exaggerated (range for the sake of range), and the grammatical structures used should be relatively authentic and natural.

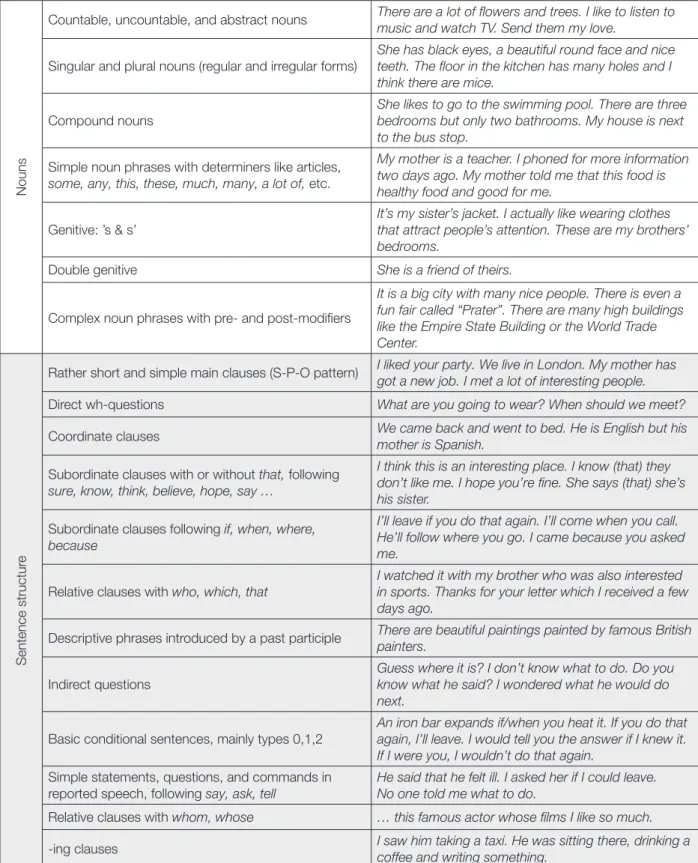

The following table1 illustrates which grammatical features have been identified as being characteristic and indi- cative of L2 language competence in the E8 testing context. This overview is not meant to capture all language features a test taker should use when writing a text, but raters should look for examples of linguistic features based on this list and then decide whether range and accuracy have been demonstrated.

1 Based on the English Grammar Profile (http://www.englishprofile.org/english-grammar-profile) and the Cambridge handbooks for the KET exam (www.cambridgeenglish.org/images/168174-cambridge-english-key-for-schools-handbook-for-teachers.pdf) and the PET exam (www.cambridge- english.org/images/168150-cambridge-english-preliminary-teachers-handbook.pdf)

Key features (in increasing complexity) Examples of use/functions

Verbs (verb forms)

Basic regular and irregular verb forms We went to the cinema. I lived in a small village.

(Verb+) infinitives …something to eat; I want to buy a coat

Gerunds (-ing form) after verbs and prepositions; as subjects and objects

I like singing. I drank a cup of coffee before leaving.

Swimming is good exercise.

Simple passive forms The houses were built by a famous architect. The T-shirt is made of cotton. I was born in China.

Verb + object + infinitive (with or without to) I would like you to come. I ordered him to do it.

I helped him bake the cake.

Causative have/get I’ll get my hair cut next week. We had our house painted last year.

Tenses

Present simple states, habits, systems, and processes; with verbs not

usually used in the continuous form

Present continuous current actions

Past simple past events

Future with going to/will, shall offers, promises, predictions, plans, intentions Present perfect simple recent past with just; indefinite past with yet, already,

never, ever; unfinished past with for and since

Past continuous parallel past actions; continuous actions interrupted by the past simple tense

Present simple and continuous future meaning

Past perfect simple narrative and in reported speech

Modals

Some modals in their basic senses (in affirmative, negative, and interrogative statements)

can (ability, requests, permission); could (ability, polite requests); would (polite requests); should (advice); may (possibility); must, have (got) to (obligation)

Complex auxiliaries would rather; had better

Additional modal uses will (offer); shall (suggestion, offer); might (possibility);

mustn’t (prohibition); need (necessity); needn’t (lack of necessity); ought to (obligation)

Used to + infinitive (past habits) I used to share my room with my brother.

Adjectives/Adverbs

Different types of adjectives/adverbs Mainly used for comparing and modifying Regular and irregular forms of comparative and

superlative forms

Football is the most popular sport. It is smaller than my old phone and it isn’t very expensive. It was so beautiful. It is quite expensive. I think it was really interesting.

(not) as ... as; the same (…as) My phone was as expensive as hers. Our house is not as big as the one of our neighbour’s.

too, enough The jacket is too small. My room is big enough for me.

(not) ... enough to; too ... to

My English is not good enough to speak to them. He was too busy to write a letter. The machine is too old to work well.

Compound adjectives The boy was tall and good-looking. This is a well- known band.

Nouns

Countable, uncountable, and abstract nouns There are a lot of flowers and trees. I like to listen to music and watch TV. Send them my love.

Singular and plural nouns (regular and irregular forms) She has black eyes, a beautiful round face and nice teeth. The floor in the kitchen has many holes and I think there are mice.

Compound nouns

She likes to go to the swimming pool. There are three bedrooms but only two bathrooms. My house is next to the bus stop.

Simple noun phrases with determiners like articles, some, any, this, these, much, many, a lot of, etc.

My mother is a teacher. I phoned for more information two days ago. My mother told me that this food is healthy food and good for me.

Genitive: ’s & s’ It’s my sister’s jacket. I actually like wearing clothes that attract people’s attention. These are my brothers’

bedrooms.

Double genitive She is a friend of theirs.

Complex noun phrases with pre- and post-modifiers

It is a big city with many nice people. There is even a fun fair called “Prater”. There are many high buildings like the Empire State Building or the World Trade Center.

Sentence structure

Rather short and simple main clauses (S-P-O pattern) I liked your party. We live in London. My mother has got a new job. I met a lot of interesting people.

Direct wh-questions What are you going to wear? When should we meet?

Coordinate clauses We came back and went to bed. He is English but his mother is Spanish.

Subordinate clauses with or without that, following sure, know, think, believe, hope, say …

I think this is an interesting place. I know (that) they don’t like me. I hope you’re fine. She says (that) she’s his sister.

Subordinate clauses following if, when, where, because

I’ll leave if you do that again. I’ll come when you call.

He’ll follow where you go. I came because you asked me.

Relative clauses with who, which, that I watched it with my brother who was also interested in sports. Thanks for your letter which I received a few days ago.

Descriptive phrases introduced by a past participle There are beautiful paintings painted by famous British painters.

Indirect questions Guess where it is? I don’t know what to do. Do you know what he said? I wondered what he would do next.

Basic conditional sentences, mainly types 0,1,2

An iron bar expands if/when you heat it. If you do that again, I’ll leave. I would tell you the answer if I knew it.

If I were you, I wouldn’t do that again.

Simple statements, questions, and commands in reported speech, following say, ask, tell

He said that he felt ill. I asked her if I could leave.

No one told me what to do.

Relative clauses with whom, whose … this famous actor whose films I like so much.

-ing clauses I saw him taking a taxi. He was sitting there, drinking a

coffee and writing something.

Table 5: Overview of grammatical structures expected at CEFR level A2/B1

ii. Range versus accuracy

The focus of E8 standards is on successful communication and on language that works as stated in the curricu- lum:

Didaktische Grundsätze:

Kommunikative Kompetenz als übergeordnetes Lernziel

Als übergeordnetes Lernziel in allen Fertigkeitsbereichen ist stets die Fähigkeit zur erfolgreichen Kommuni- kation – die nicht mit fehlerfreier Kommunikation zu verwechseln ist – anzustreben. Somit sind die jeweiligen kommunikativen Anliegen beim Üben von Teilfertigkeiten in den Vordergrund zu stellen. […] Die Bereitschaft der Schülerinnen und Schüler, neue sprachliche Strukturen in den Bereichen Lexik und Grammatik anzu- wenden und dabei Verstöße gegen zielsprachliche Normen zu riskieren, ist im Sinne des übergeordneten Zieles der kommunikativen Kompetenz von zentraler Bedeutung und bei der Evaluation der Schülerleistun- gen dementsprechend einzubeziehen. (BMBWF, 2019, p. 2)

E8 testing policy gives range priority over accuracy in the sense that rich grammatical range through risk-taking is encouraged, while minor inaccuracies that do not impair communication play a less significant role. The more varied the grammatical range, the higher the band. Risk-taking, which may result in rich structures but reduced control, can even be a reason for placing a text at a higher band.

Global errors, i.e. errors that interfere with the comprehensibility of the text, will be penalised. Local errors which do not hinder communication will not automatically lead to a lower band. However, the frequency of different local errors should be taken into account when considering the band for the text.

Band 7 texts feature a good range of structures, which create natural language within the framework of the task.

The writer varies the grammatical structures the prompt elicits and may occasionally go beyond the obvious and expected. In addition to good range, a relatively high degree of grammatical control is expected. A few inaccu- racies can occur, but they will not impair communication.

Band 5 texts show a sufficient range of structures as demanded by the prompt, without moving beyond the obvious which would demonstrate a broader repertoire of grammatical resources. Occasional inaccuracies which do not impair communication might occur.

Band 3 texts feature a limited range of simple structures. This means that the grammatical structures used are mostly simple, repetitive, and hardly varied. There can be some inaccuracies which impair communication.

Band 1 texts feature an extremely limited range of simple structures. Extremely limited range results in struc- tures that hardly go beyond the learnt repertoire of beginners, for example, the repetitive use of rather short sentences with a very simple subject-predicate-object sentence pattern. In addition to structural restrictions, band 1 texts show limited control; there might be frequent inaccuracies which sometimes cause a breakdown of communication.

4.1.5. Scale Interpretation – Vocabulary

In the dimension Vocabulary, content words (nouns, main verbs, adjectives, adverbs), collocations and chunks of language that a writer uses to perform a written communicative task are considered. Like the grammar scale, the scale for vocabulary also comprises descriptors for range and control.

i. The concept of lexical range

Range refers to the breadth of vocabulary a candidate uses in a written text. In the E8 context, range must be interpreted in relation to the prompt as raters can assess only the vocabulary elicited by the prompt. The time allocation and the expected text length have an impact on range. Short tasks are likely to provide fewer oppor- tunities to demonstrate vocabulary range than long tasks. As mentioned in the previous section, short tasks have been designed to elicit A2 responses, and long tasks have been designed to elicit B1 responses.

Even a seemingly simple task can elicit a range of vocabulary. For example, a narrative description about the first few days at a new school will primarily contain words related to school, teachers, subjects, new friends, and so on, and these can be varied and modified. Writers may well produce a response that exceeds the prompt stimulus.

Raters are advised to refer to the following tools to help them assess the range of lexical items in the prompt responses:

the English Vocabulary Profile (EVP)2, which provides a rich database of information on vocabulary for each CEFR level

the Cambridge English Key English Test (KET) Vocabulary List

the Preliminary English Test (PET) Vocabulary List

Both Cambridge resources contain examples of words and topic lists considered to be representative of A2 and B1 CEFR level descriptors, respectively.

ii. Range versus accuracy

As with grammar, E8 testing policy gives range priority over accuracy for vocabulary. Minor inaccuracies that do not impair communication may occur, but the focus is on lexical range. The text must include vocabulary that is relevant and appropriate to the topic and used in a way that expresses ideas meaningfully. Texts with familiar, high-frequency vocabulary will probably have fewer mistakes. However, it is E8 policy to encourage test takers to venture out of their safe language zone by rewarding lexical risk-taking.

Band 7 texts show a good range of vocabulary through a broad and generally accurate selection of content words and phrases. Formulations will sometimes be varied to avoid repetition, possibly with one or more expressions that stand out and exceed expectations. Even more complex ideas will be expressed using vocabulary that is generally accurate.

Band 5 texts display a sufficient range of mostly high frequency words as demanded by the prompt, without moving beyond the obvious which would demonstrate a broader range of vocabulary. A few major errors may occur, particularly when more complex ideas are being communicated.

Band 3 texts contain a rather narrow repertoire of high frequency words, but the simple ideas that are commu- nicated are mostly understandable even if there is some inaccurate vocabulary. These texts are likely to include phrases lifted from the prompt to compensate for lexical limitation.

Band 1 texts will include only a few very high-frequency content words, which are more often than not inaccu- rate and inappropriate. Heavy lifting from the prompt and/or the use of L1 words are typical features of these texts, and this will cause frequent breakdown in communication.

Some lifting of vocabulary from prompts is almost inevitable. However, good writers adapt and incorporate words and phrases from the prompt to accomplish the communicative task successfully. This is a skill that needs to be acknowledged positively.

An aspect of lexical accuracy that raters need to address is spelling. It is common practice amongst teachers to take marks off for incorrect spelling. However, the emphasis on successful communication is central to the E8 context. A text containing many spelling mistakes, in particular mistakes that change the whole meaning of a word, is likely to disturb the reader and cause a breakdown of communication. However, slight ‘slips of the hand’ and minor errors in spelling that do not change the meaning of the word (e.g. especialy for ‘especially’) should not be penalised. It is the lexical range that is more important than accuracy, and a text might merit one of the higher bands despite inaccuracies.

2 Available at: http://www.englishprofile.org

4.2. Rater Training and the Rating Process

The rating scale and associated rater training are key parameters of scoring validity. It is important to create a common understanding of the scale and how to use it (Weigle, 2002) as raters differ markedly in various ways:

their lenience, bias towards candidates and/or tasks, consistency in rating behaviour, and in their actual inter- pretation of the scale. These differences elevate the importance of rater training as consistency in applying the rating scale is a vital factor in the valid assessment of writing (Shaw & Weir, 2007). Therefore, a rater training programme was devised for the E8 Writing Test. Information about rater training and the rating process for the 2013 administration of the E8 Writing Test can be found in Gassner et al. (2011).

4.2.1. Rater Training

Rater training in the context of the 2019 E8 Writing Test administration follows a structured, sequential approach. Only those teachers who had already been trained and worked as raters for the 2013 administration of the E8 Writing Test were invited to participate in the rater training for the 2019 examination. The partici- pating raters come from all nine federal states, and represent the two school types in lower secondary (APS &

AHS) in inner cities and the countryside. They represent both genders.

The 2019 training consists of three parts:

1. Brush-up 2. Standardisation 3. Familiarisation

The purpose of the brush-up module is to familiarise the raters with the changes to the test: the E8 Writing Test Specifications, the writing tasks, and the amendments to the rating scale descriptors. Next, the raters undergo a standardisation procedure in order to ensure that they interpret the rating scales and the prompts as intended by the scale and prompt developers. Finally, the familiarisation phase prepares raters to rate the actual texts produced by test takers during the E8 Writing Test. Each rater is familiarised with three writing prompts.

Benchmarked performances help raters to gain an understanding of the scale and of the prompt in relation to the scale. After the training, raters receive their allocation of texts to be rated.

4.2.2. The Rating Process

Each rater receives approximately 400 texts to be rated within six weeks. BIFIE provides a secure online platform (CORA), where the raters enter their ratings for each individual text. In order to allow for post-test analysis of rater behaviour, a significant number of texts are double or even multiple marked. This is necessary to determine rater behaviour such as leniency, severity, and consistency. Identifying these specific traits is important in order to report fair scores.

As BIFIE uses a secure platform for raters to log scores, rater behaviour and progress can be monitored during the rating process. Thus, texts marked zero can be analysed immediately and – if necessary – can be sent back to the rater (e.g. in a situation where only one rater has given a multiple marked text a zero score).

5. Test Administration in 2019

As previously mentioned, test administration in 2019 differs from the administration in 2013. While in 2013 the whole cohort of 8th year pupils was tested in their writing ability, in 2019 only 10% of the cohort (n = 8000 pupils in approximately 400 classrooms) sat the E8 Writing Test.

The E8 Writing Test is the final part of the E8 Test. The test commences with listening, continues with reading, and finally a sample of pupils take the writing part. The E8 Writing Test contains two sections. Section 1 consists of a short writing task with an expected response of 40 to 70 words. Section 2 consists of a long writing task with an expected response of 120 to 180 words. The two texts are assessed separately using the E8 Writing Rating Scale.

The total testing time available for the E8 Writing Test is 45 minutes including 5 minutes for administration at the beginning (handing out of test booklets) and 5 minutes for administration at the end of each writing phase (word count and collecting of test booklets). The total time allocated for writing is 35 minutes. The short task is completed in 10 minutes, and the long task in the remaining 25. Both time allocations include time for basic editing, and test takers are prompted to edit their texts by the test administrators before the allocated time expires. The short scripts are collected after 10 minutes to guarantee that the time frame provided for the two writing tasks is tightly controlled.

6. Reporting and Feedback

The purpose of the E8 Standards Test is to provide feedback on the English competence of Austrian pupils in year 8 with particular focus on system monitoring. As shown in table 6 below, feedback is provided at three different levels:

1. printed reports for system-monitoring purposes, which are distributed to the Federal Ministry of Education, Science, & Research; regional governments; education authorities; and local authorities;

2. online feedback for schools (headteachers, teachers, school boards) for site-specific quality assurance;

3. online feedback for pupils to support individual learning development.

Type of feedback Target group Purpose

Printed reports

Federal ministry

System-monitoring Regional governments and education authorities

Local education authorities

Online feedback

Site-specific quality assurance School reports:

Feedback for head teachers and school boards Feedback for teachers

Feedback for pupils Individual learning

development Table 6: Types and purposes of E8 test feedback (adapted from Siller & Kulmhofer, 2018)

7. References

BMBWF. (2019). Lehrpläne der Pflichtgegenstände (Lebende Fremdsprachen). Retrieved from BMBWF website:

https://bildung.bmbwf.gv.at/schulen/unterricht/lp/ahs8_782.pdf

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assess- ment. Cambridge: CUP. Retrieved from https://rm.coe.int/1680459f97

Cumming, A. (2015). Theoretical orientations to L2 writing. In R. M. Manchon & P. K. Matsuda (Eds.), Handbook of second and foreign language writing (pp. 65–90). Boston: de Gruyter Inc.

Field, J. (2004). Psycholinguistics. The Key Concepts. London: Routledge.

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1980). The cognition of discovery: Defining a rhetorical problem. College com- position and communication, 31(1), 21–32.

Gassner, O., Mewald, C., Brock, R., Lackenbauer, F., & Siller, K. (2011). Testing Writing for the E8 Standards:

Technical Report 2011. Salzburg. Retrieved from https://www.bifie.at/system/files/dl/bist_Technical-Report2- E8_2011-09-26.pdf

Gassner, O., Mewald, C., & Sigott, G. (2008). Testing Writing: Specifications for the E8 Standards Writing Tests:

LTC Technical Report 4. Retrieved from Universität Klagenfurt website: http://www.uni-klu.ac.at/ltc/down- loads/LTC_Technical_Report_4.pdf

Grabe, W., & Kaplan, R. B. (1996). Theory and Practice of Writing. An Applied Linguistic Perspective. London:

Longman.

Kulmhofer, A., & Siller, K. (2018). The development of the Austrian Educational Standards Test for English Writing at grade 8. In G. Sigott (Ed.), Language Testing and Evaluation: Vol. 40. Language Testing in Austria:

Taking Stock (pp. 129–151). Berlin: Peter Lang.

Myles, J. (2002). Second Language Writing and Research: The Process and Error Analysis in Student Texts.

The Electronic Journal for English as a Second Language, 6(2). Retrieved from http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/

issues/volume6/ej22/ej22a1/?wscr

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (1987). Knowledge telling and knowledge transforming in written composition.

Advances in Applied Psycholinguistis, 2, 142–175.

Shaw, S. D., & Weir, C. J. (2007). Examining Writing: Research and practice in assessing second language writing.

Cambridge: CUP.

Siller, K., & Kulmhofer, A. (2018). The development of the Austrian Educational Standards Test for English Reading at grade 8. In G. Sigott (Ed.), Language Testing and Evaluation: Vol. 40. Language Testing in Austria:

Taking Stock (pp. 85–108). Berlin: Peter Lang.

Weigle, S. C. (2002). Assessing Writing. Cambridge: CUP.

8. Appendices

i. E8 Writing Rating Scale ii. Exemplar Writing Prompts iii. Model Ratings