DISS. ETH NO. 26754

Beyond Gini Coefficients – Distributional Effects at Different Units of Analysis

A thesis submitted to attain the degree of DOCTOR OF SCIENCES of ETH ZURICH

(Dr. sc. ETH Zurich)

presented by REGINA PLENINGER

M.A. in Economics, University of Zurich B.Sc. in Economics, University of Munich

B.A. in Political Science and Law, University of Munich born on 26.08.1990

citizen of Germany

accepted on the recommendation of Prof. Dr. Jan-Egbert Sturm, examiner

Prof. Dr. Bo E. Honor´e, co-examiner

2020

“To achieve great things, two things are needed; a plan, and not quite enough time.”

— Leonard Bernstein, Composer, Conductor and Pianist

To my parents, Artur and Galina

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Jan-Egbert Sturm, for offering me the opportunity to conduct this dissertation at the Chair of Applied Macroeconomics and for his guidance through each stage of the process. In addition, I would like to thank him for being a very open-minded and helpful co-author. I would also like to thank my co-supervisor, Professor Bo Honor´e, for his many comments on previous versions of the papers and the possibility to undertake a research stay at Princeton University. He is also an excellent co-autor that taught me a lot about Econometrics.

Special thanks go also to my coauthors Jakob de Haan and Jaqueson Galimberti.

Their diligent work has strongly contributed to the success of my PhD. I am also grateful for helpful comments on the dissertation chapters by numerous conference participants, referees, and colleagues at KOF. I want to give special credit to Stefan Pichler, Michael Siegenthaler and Vera Eichenauer for sharing their knowledge on successfully presenting and publishing research projects. In addition, I would like to thank my chair, the lunch group and various other KOF colleagues for having an open door for any queries and for helping me with exam supervision.

Without the continuing support of my parents, Artur and Galina, and my sister, Julia, my studies and the completion of this dissertation would have been impossible.

My parents taught me that there is nothing that I cannot do if I put my mind to it. I also want to thank my friends for their support over the years. Finally, I want to express my highest gratitude to Florian Eckert, whose help and patience was invaluable.

Regina Pleninger

Contents

Abstract . . . xiii

Zusammenfassung . . . xv

1 Introduction 1 2 The Effects of Economic Globalization and Ethnic Fractionaliza- tion on Redistribution 7 2.1 Introduction . . . 7

2.2 Theoretical Background . . . 10

2.3 Empirical Model and Data . . . 15

2.4 Results of the Effects of Globalization and Ethnic Fractionalization on Redistribution . . . 20

2.5 Instrumental Variable Estimation Results . . . 25

2.6 Further Robustness Checks . . . 30

2.7 Conclusion . . . 34

2.8 Appendix . . . 37

3 Does the Impact of Financial Liberalization on Income Inequality depend on Financial Development? Some New Evidence 47 3.1 Introduction . . . 47

3.2 Model and Data . . . 49

3.3 Estimation Results . . . 51

3.4 Concluding Remarks . . . 52

4 The “Forgotten” Middle Class: An Analysis of the Effects of

Globalization 55

4.1 Introduction . . . 55

4.2 Previous Studies . . . 58

4.3 Data and Empirical Model . . . 61

4.3.1 Data . . . 61

4.3.2 Empirical Model . . . 64

4.4 Results: The Effects of Globalization . . . 66

4.5 Robustness Checks . . . 72

4.5.1 Additional Controls . . . 72

4.5.2 Alternative Cut-offs for the Middle Class . . . 74

4.5.3 Heterogeneity: Trade and Financial Globalization . . . 75

4.5.4 Results by Country Income Groups . . . 75

4.6 Discussion and Conclusion . . . 77

4.7 Appendix . . . 79

5 Impact of Natural Disasters on the Income Distribution 83 5.1 Introduction . . . 83

5.2 Related Literature . . . 86

5.3 Theoretical Background . . . 89

5.3.1 Mechanism Model . . . 89

5.3.2 Relationship of individual- and household-based Income In- equality . . . 93

5.3.3 Hypotheses . . . 94

5.3.4 Potential Channels . . . 94

5.4 Data Description . . . 95

5.4.1 Incomes and Income Inequality . . . 95

5.4.2 Natural Disasters . . . 97

5.5 Methodology . . . 100

5.6 Results . . . 103

5.6.1 Baseline Model Results . . . 104

5.6.2 Adaptation Channels . . . 109

5.6.3 Intensification Channels . . . 115

5.6.4 Heterogeneous Effects by Disaster Type . . . 119

5.7 Concluding Remarks . . . 124

5.8 Appendix . . . 127

6 Estimating the Effects of Intra-Household Inequality on Satisfac- tion using a Simultaneous Equation Logit Model 137 6.1 Introduction . . . 137

6.2 Simultaneous Equation Fixed-Effects Model . . . 140

6.3 Swiss Household Panel Data . . . 144

6.4 Results . . . 147

6.4.1 Binary Logit Models . . . 148

6.4.2 Binary Logit with Fixed Effects . . . 152

6.4.3 Simultaneous Equation Fixed-Effects Model . . . 154

6.4.4 Heterogeneity by Swiss Regions . . . 156

6.5 Concluding Remarks . . . 158

6.6 Appendix . . . 160

Bibliography 164

Curriculum Vitae 185

List of Figures

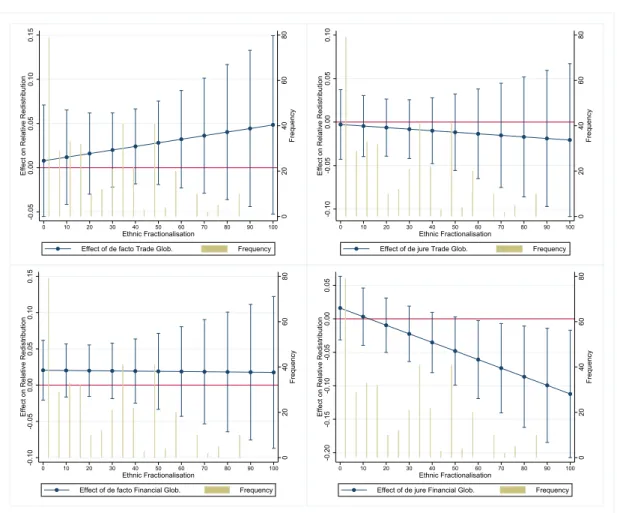

2.1 Average Marginal Effects . . . 23

2.2 Average Marginal Effects (IV & GMM) . . . 30

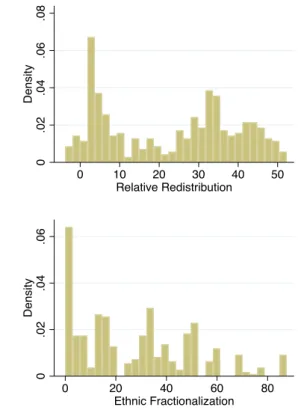

A.2.1 Histograms of Income Redistribution, Economic Globalization and Ethnic Fractionalization . . . 37

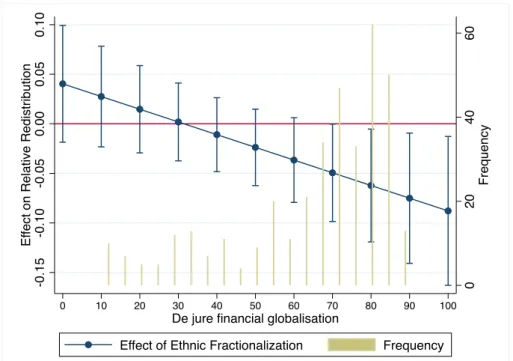

A.2.2 The Effect of Ethnic Fractionalization on Redistribution dependent on De Jure Financial Globalization . . . 38

3.1 Total Effects of Financial Liberalization . . . 52

4.1 Size of Middle Class in the United States . . . 56

A.4.1 Histograms . . . 80

5.1 Mechanism Model . . . 90

5.2 Short-term Effects on Income Distribution . . . 92

5.3 Gini-Coefficients and Palma Ratios . . . 96

5.4 Natural Disaster Count (top) and Type (bottom) . . . 99

5.5 Extended Mechanism Model . . . 102

5.6 Long-term Effects . . . 113

5.7 Impact of Previous Disasters . . . 117

A.5.1 Histogram of Previous Natural Disasters . . . 127

A.5.2 Counties in CPS Data . . . 127

6.1 Intra-Household Inequality and Satisfaction . . . 146

A.6.1 Histograms . . . 160

List of Tables

2.1 Summary Statistics . . . 19

2.2 Effects on Redistribution . . . 21

2.3 Effects on Redistribution (IV & GMM) . . . 29

2.4 Robustness Checks . . . 32

A.2.1 Summary Statistics of Additional Control Variables . . . 38

A.2.2 Additional Controls . . . 39

A.2.3 Country List . . . 40

A.2.4 First-Stage Results (IV) . . . 41

A.2.5 Income Samples . . . 42

A.2.6 Excluding Post-Crisis Data . . . 43

A.2.7 Including Technical Change into the Model . . . 44

A.2.8 Including Time Trends . . . 45

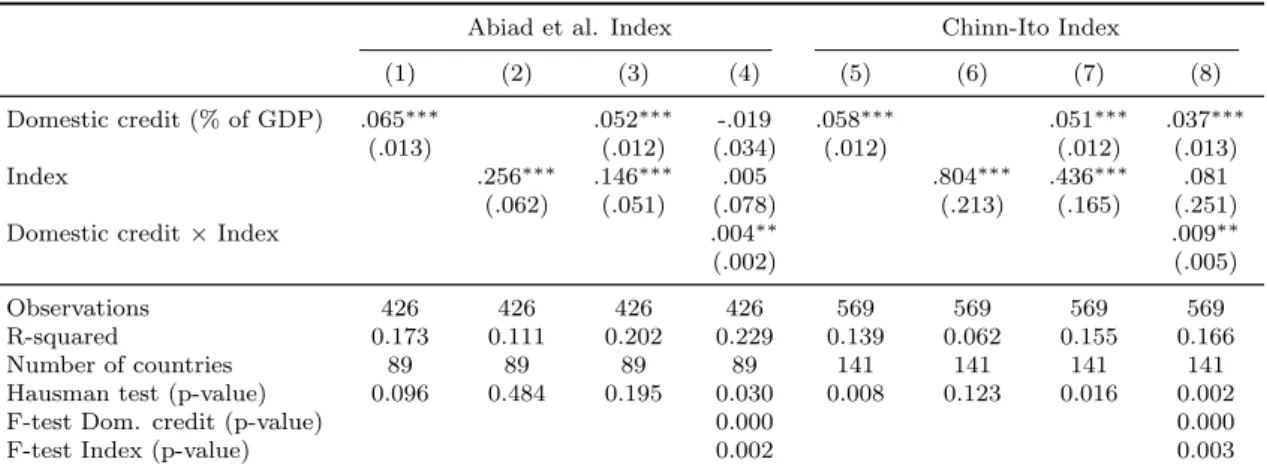

3.1 Effects on Income Inequality . . . 51

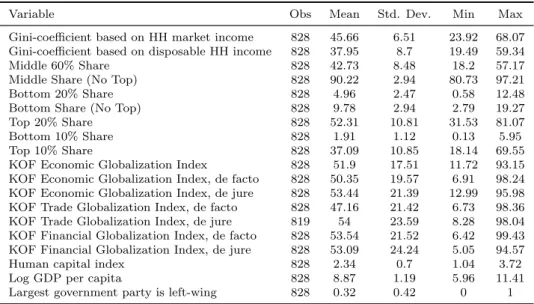

4.1 Summary Statistics . . . 63

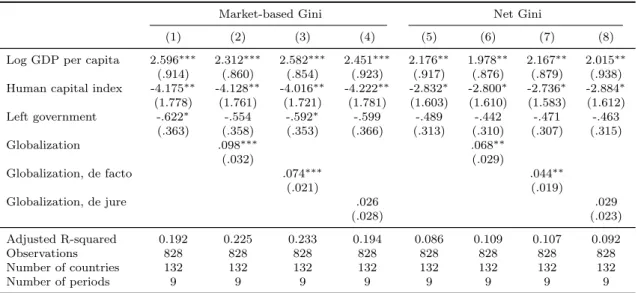

4.2 The Effect of Globalization on Gini-Coefficients . . . 67

4.3 The Effects of Globalization on Middle Class Income Shares . . . 68

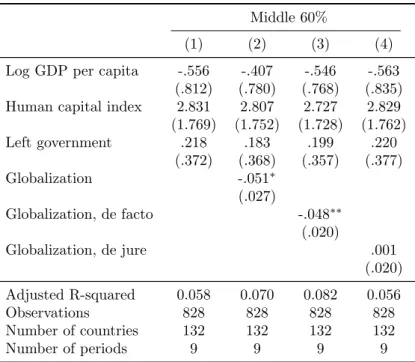

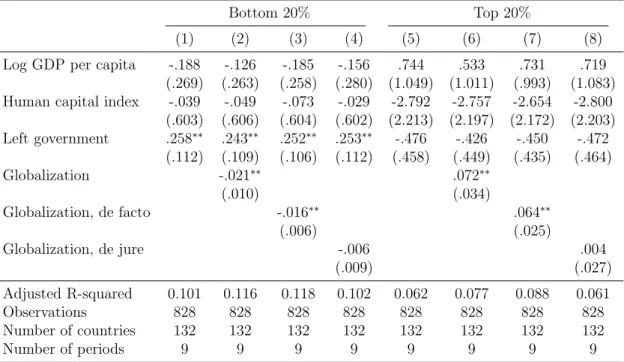

4.4 The Effects of Globalization on Tail Income Shares . . . 70

4.5 The Effects on Middle- and Low-Income Shares (No Top Income) 71 4.6 Additional Controls . . . 73

4.7 Alternative Cutoffs for Middle Class Income Shares . . . 75

4.8 Effects of Trade and Financial Globalization . . . 76

4.9 Effects of De Facto Globalization by Income Group . . . 77

A.4.1 Effects on Low and Top 10% Income Shares . . . 79

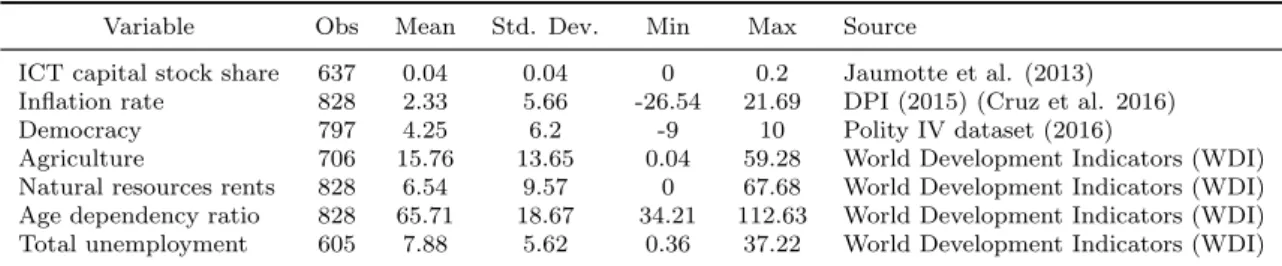

A.4.2 Summary Statistics of Additional Controls . . . 79

5.1 Disaster Types . . . 98

5.2 Migration in the United States, 1996-2017 . . . 101

5.3 Effects on Income Inequality . . . 105

5.4 Effects on Average Total Incomes . . . 106

5.5 Effects on Capital Income . . . 107

5.6 Effects on Total Earnings and Components . . . 108

5.7 Effects on Total Labor Income . . . 110

5.8 Effects on Transfers . . . 111

5.9 Effects on Total Income (Migration) . . . 114

5.10 Multiple Disasters over 5 Years . . . 116

5.11 The Effects of Severe Disasters . . . 119

5.12 Summary Statistics of Disaster Types . . . 120

5.13 Effects on Total Income by Disaster Type . . . 121

5.14 Effects on Individual-Based Income Measures . . . 122

5.15 Effects by Disaster Type (Migration) . . . 123

A.5.1 Disaster Types for Estimation . . . 128

A.5.2 Components of Total Income . . . 128

A.5.3 Summary Statistics . . . 129

A.5.4 Summary Statistics for Non-Movers . . . 130

A.5.5 Summary Statistics (Top 10% Reassigned) . . . 131

A.5.6 Summary Statistics (Bottom 40% Reassigned) . . . 132

A.5.7 Migration Reasons . . . 133

A.5.8 Interaction with Previous Disasters . . . 134

A.5.9 Various Effects of Disaster Types . . . 135

6.1 Summary Statistics . . . 147

6.2 Binary Logit Results . . . 149

6.3 Logit Results with Spouse’s Satisfaction . . . 151

6.4 Fixed-Effects Logit with Spouse’s Satisfaction . . . 153

6.5 Simultaneous Equation Fixed-Effects Model . . . 155

6.6 Simultaneous Equation Fixed-Effects Model by Region . . . 158 A.6.1 Canton List . . . 161 A.6.2 Summary Statistics by Region . . . 161 A.6.3 Simultaneous Equation Model Controlling for a New Baby . . . . 162 A.6.4 Effect on Free Time Satisfaction by Region . . . 163

Abstract

This dissertation is a collection of articles on the topic of income inequality. Each chapter is dedicated to a different element of income inequality. The first chapter gives an introduction into the topic, describes the structure of the dissertation and discusses the contribution to the existing literature. The subsequent chapters present the research articles. They are ordered by the type of inequality measure used in the analysis, namely from aggregate measures of inequality, such as redistribution and Gini-coefficients in Chapters 2 and 3, to the disaggregated measure on intra- household inequality in Chapter 6.

In the second chapter, coauthored with Jan-Egbert Sturm, we examine the ef- fect of economic globalization on income redistribution and show that the effect depends on the level of ethnic fractionalization. Using the newly constructed KOF Globalization Index, we find supportive evidence for the interactive effect of ethnic fractionalization and de jure financial globalization on redistribution. The results suggest that the total effect of de jure financial globalization on redistribution is negative in highly fractionalized countries.

The third chapter, coauthored with Jakob de Haan and Jan-Egbert Sturm, an- alyzes the effects of financial liberalization on income inequality. The chapter is closely related to the studies by Bumann and Lensink (2016) and Furceri and Loun- gani (2015). We extend the model in Bumann and Lensink (2016) by allowing for more volatility and uncertainty in financial liberalization. Using the extended model, the results show that financial development amplifies the positive effect of financial liberalization on income inequality.

The analysis in Chapter 4 sheds light on the importance of studying the middle class. The existing literature most commonly focuses on either aggregate inequality measures, top incomes or poverty lines. However, only a small number of studies attend to the middle class. This chapter, which is joint work with Jakob de Haan and Jan-Egbert Sturm, studies the effects of globalization on the income share of the middle class. Our findings suggest that globalization, proxied by the KOF Eco- nomic Globalization Index, reduces the income share of the middle class. Similarly, the income share of the poorest 20% decreases due to globalization, while that of the richest 20% increases. When we distinguish between de facto and de jure glob- alization, we find that only de facto measures have statistically significant effects on income shares and inequality measures.

During the last decades, the United States experienced an increase in the number of natural disasters as well as their destructive capability. In Chapter 5, I estimate the effects of natural disasters on the entire income distribution using county-level data in the United States. The results suggest that natural disasters primarily affect middle incomes, thereby leaving income inequality levels mostly unchanged.

In addition, the chapter examines potential channels that intensify or mitigate the effects. The findings show that social security, assistance programs and migration are important adaptation tools that reduce the effects of natural disasters. In contrast, the occurrence of multiple and severe disasters aggravate the effects.

So far, the chapters provided studies on aggregate measures, such as income inequality and redistribution, as well as different income groups of the income dis- tribution. A common assumption in inequality research is perfect equality within a household. In Chapter 6, my co-author, Bo Honor´e, and I deviate from this assumption and analyze the effects of intra-household inequality on general, finan- cial and free time satisfaction of married couples using the Swiss Household Panel (SHP). We show that reported satisfaction levels are correlated between husbands and wives and construct a simultaneous equation fixed-effects model that accounts for this dependence structure. The results suggests that intra-household inequality has a significantly negative effect on general satisfaction for husbands and a signifi- cantly negative effect on free time satisfaction for wives.

Zusammenfassung

Diese Dissertation ist eine Sammlung von Forschungsaufs¨atzen zum Thema Einkom- mensungleichheit. Jedes Kapitel widmet sich einem anderen Einkommensungleich- heitskonzept. Das erste Kapitel gibt eine Einf¨uhrung in die Thematik, beschreibt die Struktur der Dissertation und diskutiert den Beitrag zur gegenw¨artigen Literatur.

Die anschliessenden Kapitel pr¨asentieren die Forschungsartikel. Sie sind nach der Art des in der Analyse verwendeten Ungleichheitsmasses geordnet, n¨amlich von den aggregierten Ungleichheitsmassen, wie Umverteilung und Gini-Koeffizienten in den Kapiteln 2 und 3, bis hin zu dem disaggregiertem Mass der Ungleichheit innerhalb eines Haushaltes in Kapitel 6.

Im zweiten Kapitel, das gemeinsam mit Jan-Egbert Sturm verfasst wurde, un- tersuchen wir die Auswirkungen der ¨okonomischen Globalisierung auf die Einkom- mensumverteilung und zeigen, dass der Effekt vom Grad der ethnischen Fraktional- isierung abh¨angt. Anhand des neu konstruierten KOF Globalisierungsindexes finden wir wichtige Hinweise f¨ur den interaktiven Effekt der ethnischen Fraktionalisierung und der de jure finanziellen Globalisierung auf die Umverteilung. Die Ergebnisse deuten darauf hin, dass der Gesamteffekt der de jure finanziellen Globalisierung auf die Umverteilung in stark fraktionanlisierten L¨andern negativ ist.

Das dritte Kapitel, das gemeinsam mit Jakob de Haan und Jan-Egbert Sturm verfasst wurde, analysiert die Effekte der finanziellen Liberalisierung auf die Einkom- mensungleichheit. Das Kapitel steht in engem Zusammenhang mit den Studien von Bumann and Lensink (2016) sowie Furceri and Loungani (2015). Wir erweitern das Modell in Bumann and Lensink (2016), indem wir mehr Volatilit¨at und Unsicher- heit bei der Finanzliberalisierung ber¨ucksichtigen. Die Ergebnisse des erweiterten

Modells zeigen, dass die finanzielle Entwicklung den positiven Effekt der Finanzlib- eralisierung auf die Einkommensungleichheit verst¨arkt.

Die Analyse in Kapitel 4 beleuchtet die Bedeutung der Untersuchung der Mit- telschicht. Die vorhandene Literatur konzentriert sich haupts¨achlich auf aggregierte Ungleichheitsmasse, Spitzeneinkommen oder Armutsgrenzen. Allerdings befassen sich nur wenige Studien mit der Mittelschicht. Dieses Kapitel, das gemeinsam mit Jakob de Haan und Jan-Egbert Sturm erstellt wurde, untersucht die Auswirkungen der Globalisierung auf den Einkommensanteil der Mittelschicht. Unsere Ergebnisse zeigen, dass die Globalisierung, die mit dem KOF-Globalisierungsindex gemessen wird, den Einkommensanteil der Mittelschicht reduziert. Der Einkommensanteil der ¨armsten 20% sinkt ebenfalls in Folge der Globalisierung, w¨ahrend derjenige der reichsten 20% steigt. Wenn wir zwischen de facto und de jure Globalisierung unter- scheiden, stellen wir fest, dass nur de facto Masse statistisch signifikante Effekte auf Einkommensanteile und Ungleichheitsmasse aufweisen.

W¨ahrend der letzten Jahrzehnte erlebten die Vereinigten Staaten eine Zunahme der Anzahl von Naturkatastrophen und ihrer Zerst¨orungskraft. In Kapitel 5 sch¨atze ich die Effekte von Naturkatastrophen auf die gesamte Einkommensverteilung mit Hilfe von Daten auf County-Ebene in den Vereinigten Staaten. Die Resultate deuten darauf hin, dass Naturkatastrophen vor allem die mittleren Einkommen treffen, so dass das Niveau der Einkommensungleichheit weitgehend unver¨andert bleibt.

Dar¨uber hinaus untersucht das Kapitel m¨ogliche Kan¨ale, die die Auswirkungen verst¨arken oder mildern. Die Ergebnisse zeigen, dass Sozialversicherungen, Hilfs- programme und Migration wichtige Adaptionsinstrumente sind, die potentielle Ef- fekte von Naturkatastrophen mindern. Im Gegensatz dazu versch¨arft das Auftreten mehrfacher und schwerer Katastrophen die Auswirkungen.

Bisher wurden in den Kapiteln Studien zu aggregierten Massen, wie Einkom- mensungleichheit und Umverteilung, sowie zu verschiedenen Einkommensgruppen der Einkommensverteilung aufgef¨uhrt. Eine g¨angige Annahme in der Ungleich- heitsforschung ist die perfekte Gleichheit innerhalb eines Haushaltes. In Kapitel 6 weichen mein Koautor, Bo Honor´e, und ich von dieser Annahme ab und unter- suchen die Effekte der innerh¨auslichen Ungleichheit auf die allgemeine, finanzielle

und Freizeitzufriedenheit von Ehepaaren mit Hilfe des Schweizer Haushaltspanels (SHP). Wir zeigen, dass die angegebene Zufriedenheit zwischen Ehem¨annern und Ehefrauen korreliert ist und konstruieren ein simultanes Gleichungsmodell mit fixen Effekten, das diese Abh¨angigkeitsstruktur ber¨ucksichtigt. Die Ergebnisse legen nahe, dass die Ungleichheit innerhalb des Haushaltes einen signifikant negativen Effekt auf die allgemeine Zufriedenheit der Ehem¨anner und einen signifikant negativen Effekt auf die Freizeitzufriedenheit der Ehefrauen hat.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The research on income inequality increased tremendously in the last decades. This development is mainly attributed to rising income inequality levels especially from the mid-1990s to the present. In addition, income inequality research shifted from the analysis of wage inequality in the labor markets to a number of other topics, such as economic and other governmental policies, taxation, institutions and corpo- rate governance. In these numerous research areas, income inequality serves as an explanatory variable for various outcomes, such as economic growth and conflict, but also as a dependent variable. In the latter case, many studies analyze potential determinants of income inequality. In this thesis, my co-authors and I investigate whether economic globalization, financial liberalization and natural disasters deter- mine income inequality. In addition, we use a measure for intra-household inequality as an explanatory variable for the effects on satisfaction in Chapter 6.

Another strand of literature expanded the research on wealth inequality, such as, among others, Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman. Their work contributed to the popularity of this research area. Piketty’s research provides a more detailed view on inequality dynamics than the initially proposed relationship between inequality and economic growth by Kuznets (1955). In his famous book

“Capital in the 21th Century”, Piketty (2014) strives to explain the main driving forces of the late increase in income and wealth inequality across the world. One argument that he makes is the size of the gap between the rate of return on capital

and the economy’s growth rate. In particular, the rate of return is larger than economic growth, thereby exacerbating wealth inequality over time. However, this argument is less adequate to explain the recent rise in income inequality, particularly in labor income inequality. Piketty (2014) suggests that increases in labor income inequality is mainly driven by policies and labor-market mechanisms, such as the supply and demand for skills and education. One example is the large increase in top income shares, which is additionally spurred by inequalities in educational opportunities.

It is crucial to differentiate between income and wealth inequality. Income in- equality studies wages, business income and other sources of labor income from employment or self-employment as well as capital income, which encompasses any income streams from capital, such as interest and dividends. In contrast, wealth includes savings and ownership of property and, thus, can be summarized as the total value of all assets minus liabilities.

This thesis focuses on topics related to income rather than wealth inequality. In particular, I study different dimensions of income inequality at different units of anal- ysis. The different dimensions of income inequality illuminate various components of the income distribution. The chapters in this thesis are ordered from the most ag- gregate measures of income inequality, namely redistribution and Gini-coefficients, to intra-household inequality. In Chapter 2, my co-author and I estimate the effects of economic globalization on redistribution. We measure redistribution as the rel- ative difference between market-based and after-tax Gini-coefficients. In addition, we show that the effect depends on ethnic fractionalization, which is defined by the probability that two randomly drawn individuals belong to the same ethnic group.

Countries with high levels of ethnic fractionalization are redistributing, on average, less. Given the aggregate measure on redistribution, our analysis is conducted us- ing cross-country panel data. The main contribution of this chapter is the ethnic fractionalization element. Further, we provide a more distinct view on economic globalization by distinguishing the effects of trade and financial globalization. Pre- vious literature shows inconclusive results about the effects of globalization. Using

these additional elements, we strive to improve our understanding on why the results in the literature are diverging.

The same unit of analysis is applied in Chapters 3 and 4. Both chapters use countries as the unit of analysis. In Chapter 3, my co-authors and I analyze the effects of financial liberalization on income inequality using Gini-coefficients. This study is to some degree related to the first one as financial liberalization and fi- nancial globalization share common aspects. In this study, we shortly discuss the implications of a model proposed by Bumann and Lensink (2016). The main discus- sion point is the intervening effect of financial development. Bumann and Lensink (2016) suggest that the positive effect of financial liberalization on income inequality is smaller in financially developed countries. In contrast, we show that if their model is extended by including more volatility and uncertainty, financial development can have an amplifying effect on income inequality. Hence, the main contribution of this short chapter is the extension of their model.

The first two chapters indicate that conclusively providing determinants of in- come inequality is not conspicuous. Different intervening effects come into play.

Furthermore, using aggregate measures has at least two caveats. First, aggregate measures, such as the Gini-coefficient, smooth over a lot of variation in the income distribution. Second, the measures often completely disregard parts of the income distribution. The most prominent example is the Palma ratio, which relates the income share of the top- to the one of the low-income group, thereby neglecting middle incomes completely.

In Chapter 4, my co-authors and I use country-level data on income percentiles to generate different income groups, namely a low-, middle- and high-income group.

The aim is to emphasize the “forgotten” middle class. Changes in the middle class income share often do not affect aggregate income inequality measures. For this reason, the literature mainly focuses on top-income shares or poverty rates. However, the middle class is a non-negligible part of the income distribution. In addition, the middle class is an important source for tax collection and economic growth. From a political economy perspective, the median voter is located in the middle class.

Even if middle class changes do not affect income inequality measures, the income

group is still relevant for various political, economic and social outcomes. Therefore, analyzing the dynamics in middle class income shares is highly relevant. In Chapter 4, we address the topic of economic globalization once again. In particular, we estimate the effects of economic globalization on the income share of the middle class. Our results suggest that the income shares are decreasing. Their decrease is completely absorbed by the top-income group, because low-income shares decrease as well. Given these effects at the tails of the income distribution, income inequality increases. The main contribution of this chapter is to highlight the importance of the middle class and provide heterogeneous effects of globalization by income groups.

In the previous chapter, my co-authors and I use income shares because we only had data on income percentiles. In my single-authored chapter, I analyze the effects of natural disasters on incomes across the entire income distribution using county- level data in the United States. Due to the reasons stated above, I had to restrict my unit of analysis to one country. In the United States, natural disasters occur frequently and with geographic variation. In addition, the US experiences all types of natural disasters, such as hurricanes, fires, tornadoes and volcanic eruptions. Hence, US counties are well-suited units of analysis. Given the immense disruption of the economy caused by natural disasters, effects on incomes are expected. The results suggest that middle incomes are affected the most.

Unlike the results in the previous chapter, low- and high-income groups are not significantly affected by natural disasters. As a consequence, I do not find any ef- fects on Gini-coefficients. This study shows, even more than the previous one, that the analysis of the entire income distribution is crucial to understand the effects.

Since previous studies restrict their analysis to only one natural disaster or only one location, this chapter contributes to the literature by providing a full analysis of all natural disasters on the entire income distribution. Using all natural disasters allows to extract heterogeneous effects of different types of disasters. Furthermore, this study makes two additional contributions. First, the study investigates chan- nels that reduce or amplify the effects of natural disasters. Examples are social security, migration and the increased frequency of natural disasters. Second, it dis- cusses the implications of using household-based measures, which explicitly assume

equality within a household. In order to show the consequences of this assumption, results are estimated using household- and individual-based incomes. Household- based measures do not account for intra-household inequality, but individual-level measures neglect income sharing within a household. Therefore, the individual- and household-based estimates provide upper and lower bounds for the true effects.

The last chapter builds upon this argument and analyzes the effects of intra- household inequality on satisfaction in Switzerland. Hence, the unit of analysis shifts to the individual level. The aim is to test whether the share of income that household members contribute to household income is affecting their satisfaction levels. In the analysis, we only include married couples and provide the results for husbands and wives separately. In addition, we introduce a cross-equation dependence between the spouses. We show that reported satisfaction levels are correlated for husbands and wives. In particular, our claim is that husbands are more likely to report being satisfied if the wife reports it as well. This extension is a novelty in the literature and requires the construction of a new estimator. Following Schmidt and Strauss (1975) and Honor´e and Kyriazidou (2018), we develop a simultaneous equation fixed- effects estimator that accounts for this dependence. We find that intra-household inequality has negative effects on satisfaction. In addition, we show that the effects are heterogeneous across the French- and German-speaking regions of Switzerland.

Each chapter has a unique contribution to the literature. The combined thesis provides a good overview on how income inequality can be measured and analyzed.

In addition, the thesis presents some insights on how these measures are related to each other and what their implications are. The chapters use different units of analysis, types of datasets and empirical approaches. In summary, the thesis contributes to the literature by showing that the analysis of income inequality is extremely rich in variety.

Chapter 2

The Effects of Economic Globalization and Ethnic Fractionalization on

Redistribution

12.1 Introduction

The impact of globalization on the economy and politics has been discussed exten- sively in recent years. Globalization is enhancing economic growth by facilitating the possibilities to trade internationally, leading to a specialization of production processes and an increase in the variety of goods and services offered (Wade, 2004).

Thus, there is quite some consensus that globalization leads to a prospering economy (see, e.g. Dreher (2006); Dollar and Kraay (2004); Villaverde and Maza (2011)).

However, stronger competition associated with globalization is often suggested to have increased inequality. Gozgor and Ranjan (2017) show that globalization in- creases market-based income inequality and redistribution. Similarly, Bergh and

1This chapter is based on Pleninger and Sturm (2020), published inWorld Development.

Nilsson (2010) find that trade liberalization as well as (lagged) economic global- ization increase after-tax income inequality, thereby implying that governments are either unwilling or unable to countervail the potentially adverse effects through re- distribution.

This paper focuses on differences in the political reaction to counteract the ef- fects of globalization by redistributing income through the tax and subsidy system.

The analysis of Gozgor and Ranjan (2017) is the paper most related to our study.

They estimate the effect of globalization on redistribution and find that globalization increases redistribution, which is measured by the difference between market-based and after-tax Gini-coefficients. Our analysis deviates from the empirical model by Gozgor and Ranjan (2017) in various ways. In particular, we investigate to what extent ethnic fractionalization might be a conditioning factor on the willingness or ability of the government to engage in redistributive policies. We define ethnic frac- tionalization by the probability that two randomly drawn individuals belong to the same ethnic group, where a higher value of ethnic fractionalization is associated with a lower probability. Already Becker (1957) suggested that countries with a high de- gree of ethnic fractionalization are expected to favor lower levels of redistribution. In addition, Houle (2017) suggests that the effect of income inequality on redistribution is weaker if the poor fraction of the population is ethnically fractionalized. In our study, we combine the findings of Gozgor and Ranjan (2017), Becker (1957) as well as Houle (2017) and present an analysis of the effects of globalization on redistribu- tion dependent on ethnic fractionalization. The ethnic fractionalization argument is thereby similar to the one in Houle (2017). To the best of our knowledge, there is no other study that looks at the link between redistribution, globalization and ethnic fractionalization.

In a world in which on the one hand increased competition disciplines govern- ments and on the other hand the electorate wants to be compensated for the in- creased uncertainty related to globalization, we hypothesize that the latter will only be able to truly compensate for the first in societies with a low degree of ethnic fractionalization, i.e. in more homogeneous environments in which the willingness to redistribute is higher. Furthermore, we analyze whether government-induced de

jure measures, such as import restrictions, or actual de facto flows of goods and services trigger redistribution. We believe that in particular de jure changes in the degree of globalization can give rise for compensating redistribution measures during the political process. The main argument behind this hypothesis lies in the nature of de jure globalization measures. In particular, de jure measures as well as redistri- bution levels are both directly determined by government policy. In order to at least partially compensate for the possible adverse consequences of globalization-inducing decisions, an increase in the de jure degree of globalization is likely to trigger ad- ditional redistribution decisions in the political process. In order to differentiate between de facto and de jure measures of globalization, we exploit a new feature of the KOF Globalization Index. Its latest edition provides a distinction between de facto and de jure measures of globalization. De facto measures incorporate ac- tual flows in the economy, whereas de jure encompasses regulatory features, such as import and capital restrictions.

In our study, we separate the results for trade and financial globalization. Whereas the trade globalization literature often finds that this form of globalization does not have a strong impact on inequality and thereby does not have to trigger redistri- bution measures (Jaumotte et al., 2013; Richardson, 1995; Reuveny and Li, 2003), recent literature focusing on financial integration note clearly an upward pressure on inequality (De Haan and Sturm, 2017; De Haan et al., 2018; Furceri and Loungani, 2018; Van Velthoven et al., 2019). Following this more recent line of literature, we expect that the inequality pressure stemming from financial integration is raising redistribution. By using the newly revised KOF Globalization Index that distin- guishes between trade and financial globalization, we are the first to simultaneously look into these different dimensions of globalization and ethnic fractionalization as well as their impact on redistribution.2 Hence, the main contribution of this paper is

2Another study that distinguishes between trade and financial as well as de facto and de jure measures of globalization is Jha and Gozgor (2019). Their empirical results suggest that, on average, trade globalization decreases taxation in labor-abundant economies, but increases it in capital-abundant economies. In contrast, financial globalization has a negative effect on taxation.

Most importantly, their analysis focuses on taxation rather than overall redistribution. Even though the authors claim that taxation is mainly used for redistribution in their theoretical model, taxation is still not equivalent to general redistribution. In addition, their analysis focuses

to provide evidence that ethnic fractionalization, in addition to different dimensions of globalization, is an important driver for the heterogeneous effects of globalization on redistribution.

In total, we cover 62 countries over eight 5-year periods from 1975 to 2014.3 Using a standard fixed-effects panel regression framework, our results show that the effect of de jure financial globalization on redistribution depends on the level of ethnic fractionalization. In particular, the effect of globalization on redistribution is strongly negative for highly fractionalized countries, but statistically insignificant for more ethnically homogeneous countries. There are no effects of trade globalization using the same model. In addition, de facto measures are also not statistically significant. These results are confirmed by instrumental variable estimations and various robustness checks. In particular, we show that the results hold when a lagged dependent variable, the ICT share, or time trends are included, and when the sample is restricted to the pre-crisis time. In addition, we test the effects by income group and find that the effects of de jure financial globalization are driven by high-income countries.

The next section provides an overview of the existing literature related to income redistribution, globalization as well as ethnic fractionalization. Section 2.3 describes our data and the empirical model that we use to estimate the effects of globalization and ethnic fractionalization on redistribution. In Section 2.4, we present the fixed- effects regression results. In order to account for potential endogeneity concerns, we employ an IV estimation in Section 2.5. Robustness checks are provided in Section 2.6. The last section concludes.

2.2 Theoretical Background

The literature on the effects of globalization on redistribution can be characterized by two opposing theoretical arguments. According to the “compensation effect”

on the effect of globalization on taxation depending on capital-labor ratios. Our study introduces the ethnic component to explain the differing effects between countries.

3A list of countries is provided in Table A.2.3.

argument, globalization creates both increased demand for insurance against exter- nal risks and the need to distribute its economic gains fairly across different groups within society (see, e.g. Rodrik (1998); Burgoon (2012)). Based on this line of think- ing, there is quite some consensus in the literature that globalization leads to more redistribution (see, e.g. Leibrecht et al. (2011); Bergh and Nilsson (2010); Meinhard and Potrafke (2012)). In contrast, according to the “disciplining effect” argument, globalization limits the government’s ability to redistribute, causing a decline in the level of redistribution (see, e.g. Dreher et al. (2008); Onaran et al. (2012)). For in- stance, an increase in globalization levels leads to less restrained movement of capital and labor. In order to attract capital and high-skilled labor, governments engage in tax competition (Sinn, 1997). As a result, governments collect less taxes which weakens their redistribution capacity and, hence, overall redistribution. In general, both effects occur when confronted with increased globalization levels. Governments face amplified pressure while trying to countervail potential negative consequences.

However, the respective magnitudes determine whether the compensating or the disciplining effect dominates.

Redistribution connects income inequality to the role of government in preventing any undesired consequences of political and economic developments. Governments appear generally inequality-adverse and, thus, strive to counteract actual or poten- tial rises in income inequality. A common claim is that increasing specialization due to globalization tends to strengthen income differences within countries. Dreher and Gaston (2008), Potrafke (2015) and Gozgor and Ranjan (2017) suggest a posi- tive effect of globalization on income inequality using the KOF Globalization Index.

Combining this suggests that inequality-averse governments increase the level of re- distribution after they implement globalization-increasing de jure measures. There is some literature on rising disparities in income leading to investment-reducing so- cial unrest, political instability and diminishing property rights security (Keefer and Knack, 2002). In addition, several papers provide evidence that inequality may reduce the pace and durability of growth (see, for instance, Persson and Tabellini (1994); Berg et al. (2012); Ostry et al. (2014)). Furthermore, Sturm and de Haan

(2015) show that countries with similar market-based economic systems exhibit dif- ferences in income inequality before and after redistribution, thereby implying that redistribution policies differ tremendously across countries. Hence, redistribution policies are likely to be shaped by other factors than merely the type of economic system.

Meltzer and Richard (1981) show that redistribution levels depend on the posi- tion of the decisive voter in the income distribution. Income distributions are skewed to the right, implying that the median voter has an income below the mean and, therefore, is in favor of more redistribution (Janeba and Raff, 1997). Alesina and Rodrik (1994), Alem´an and Woods (2018), Gr¨undler and K¨ollner (2017), Mahler (2008), Houle (2017) and Scervini (2012) confirm this hypothesis. However, there are also studies, like Luebker (2014), that find no such direct link. Following this broader literature, we will include market-based income inequality as a control to test whether more inequality triggers more redistribution.

A recent line of research suggests that ethno-linguistic fractionalization can help explain cross-country differences in income redistribution (cf. Desmet et al. (2012);

Sturm and de Haan (2015); Haller et al. (2016)). Ethnic fractionalization has an effect on redistribution through a variety of channels, such as the provision of public goods (Alesina and La Ferrara, 2000; Vigdor, 2004; Habyarimana et al., 2007), the potential for conflict (Collier and Hoeffler, 2004; Blimes, 2006) as well as the level of corruption (Easterly and Levine, 1997; Shleifer and Vishny, 1993). Haller et al.

(2016) focuses on ethnic diversity and historic ethnic exploitation, such as slavery, to explain international variations in within-country income inequality. A crucial assumption is that a society with a high level of ethnic variety faces difficulties when trying to organize and push general interests onto the political spheres. This implies an inherent inequality between the powerful and the ethnic minorities persistently imprinted by former power relations.

We build upon and extend this line of literature and analyze whether the effect of globalization on redistribution depends on the level of ethnic fractionalization. In particular, we hypothesize that the prevalence of either the compensating or disci- plining effect is depending on ethnic fractionalization. The literature suggests that

the allocation of resources is, among others, determined by the ethnic composition of a country’s population. We believe that the level of ethnic fractionalization heav- ily influences the distribution of the benefits coming from globalization. Sturm and de Haan (2015) argue that the impact of ethno-linguistic fractionalization is condi- tional on the level of economic freedom, a proxy for capitalism. Countries that are highly fractionalized exhibit less income distribution, while capitalist countries with low levels of fractionalization redistribute to a higher degree. Gr¨undler and K¨oll- ner (2018) uncover negative effects of ethnic and cultural diversity on redistribution.

Their main hypothesis is based on Luttmer’s (2001) “racial group loyalty” argument, which states that individuals are more likely to support redistribution policies when they benefit their own racial group. Similarly, Eger (2010) concludes that immigra- tion negatively affects the support for the welfare state in Sweden. Furthermore, Alesina and La Ferrara (2005) suggest that as a country becomes ethnically more fractionalized, it chooses to have a smaller size of government due to heterogeneous preferences, which lower the marginal utility of public goods thereby leading to a decrease in overall public good provision. Consequently, redistribution levels are reduced.

Following the literature on ethnic fractionalization, we expect the results to di- verge substantially for different levels of fractionalization and, hence, our first and main hypothesis is that the effect of globalization on redistribution depends on the level of ethnic fractionalization.

As governments are assumed to be inequality-averse, they are inclined to balance out negative consequences of their own doing. In order to gain majorities, compro- mises are likely to occur in the political process. If policies change towards more political openness, then it is likely that these policies trigger measures of redistri- bution to directly compensate losers through the political process. For that reason, we expect that in particular de jure measures of globalization, i.e. formal trade and capital mobility restrictions, are going to be linked to redistribution policies. This reasoning would be in line with the “compensating” hypothesis stated above. How- ever, if governments are unable to increase redistribution levels due to international

pressure to keep taxes low, the compensating mechanism might be outweighed by the disciplining effect.

Our claim is that the compensating effect is either tenuous or even completely absent in highly fractionalized countries. First, a highly fractionalized society is less likely to support higher redistribution levels as benefits are more likely to be ascribed to other ethnic groups. This is in line with Luttmer’s (2001) “racial group loyalty”

argument and also applies to non-democratic countries, in which government exec- utives are less likely to compensate other groups than their own. Second, an ethnic fractionalized country has various interests and preferences, thereby exacerbating the chances to reach a consensus, which translates into overall lower government spending according to Alesina and La Ferrara (2005). Thus, the disciplining effect strongly dominates and, thereby, generates overall negative effects on redistribution.

In contrast, we hypothesize that countries with low levels of fractionalization expe- rience both, compensating as well as disciplining, effects of globalization in more equivalent proportions. Therefore, globalization is expected to have either a small or no effect on redistribution. Whether also de facto globalization, i.e. actual flows of goods and service and/or financial assets, triggers actual redistribution policies is less clear. The level of de facto globalization is primarily determined by the market economy and less directly linked to policy decisions.

In the income inequality literature, Reuveny and Li (2003) study the effects of economic openness and democracy on income inequality. Using a cross-country anal- ysis, they find that democracy as well as trade reduces income inequality, whereas foreign direct investment increases it. This suggests that different dimensions of globalization have different consequences. Therefore, we analyze the effects of glob- alization on redistribution by distinguishing between trade and financial globaliza- tion. We add to the literature by providing a comprehensive analysis for different components of economic globalization. The literature on the effects of trade on income inequality is inconclusive; trade either has an increasing, reducing or in- significant effect on income inequality (Bergh and Nilsson, 2010; Jaumotte et al., 2013; Richardson, 1995; Reuveny and Li, 2003). As a consequence, governments might effectively not have to change redistribution policies.

In contrast, financial globalization is likely to benefit mostly the higher fractions of the income distribution as they are more likely to earn capital income and be able to invest in foreign countries. De Haan and Sturm (2017) and De Haan et al.

(2018) show that financial liberalization, which is related to our de jure financial globalization measure, indeed increases income inequality. Furceri and Loungani (2018) analyze the distributional effects of capital account liberalization. Their re- sults exhibit inequality-increasing effects of this form of liberalization. In addition, Van Velthoven et al. (2019) suggest that income inequality caused by financial lib- eralization leads to more redistribution than inequality derived from other sources.

Following this line of literature, we expect in particular an effect of financial global- ization on redistribution, while trade globalization might not have a clear impact.

2.3 Empirical Model and Data

In order to analyze the effect of globalization and ethnic fractionalization on redis- tribution, we interact the two variables to capture their interdependence. We use the following empirical model to estimate the effects:

Redisti,t =β1Ineqi,t−5+β2Globi,t+β3EFi,t+β4Globi,t∗EFi,t+β5Xi,t+αi+γt+i,t, where Redisti,t is the dependent variable on redistribution. Ineqi,t−5 denotes the lagged value of market-based income inequality. Globi,t represents the globalization variables. In particular, we show results for overall economic globalization as well as its sub-components, namely de facto trade, de jure trade, de facto financial and de jure financial globalization. We include all sub-components into the estimation model in order to rule out omitted variable biases triggered by the correlation among them. For instance, the actual flow of goods (de facto trade component) depends on import restrictions (de jure trade component). EFi,t denotes ethnic fractionalization and Xi,t contains further control variables. Country- and period-fixed effects are captured byαi und γt.

Solt’s (2016) Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID), Ver- sion 7.1, provides data on income inequality in the form of Gini-coefficients for 192

countries from 1960 to 2017. In addition, the SWIID categorizes the coefficients in market-based and net (after-tax) Gini-coefficients. Market-based Gini-coefficients proxy inequality levels resulting from market processes. In contrast, after-tax Gini- coefficients result from various tax and benefit policies implemented by governmental authorities. Using both Gini-coefficients, Solt (2016) constructs a relative measure for redistribution.4 In particular, he uses the relative difference between market- based and after-tax Gini-coefficients:

Redistribution= Ginimarket−Gininet

Ginimarket ,

which gives the percentage reduction in market-based income inequality due to taxes and transfers.5 The construction of the measure is simple and transparent and thereby very useful for empirical analysis. However, the measure has one main caveat, because it falsely assumes that the pre-tax income distribution is independent of the welfare state. This is commonly referred to as the counterfactual problem since we do not observe market-based incomes in absence of any form of welfare state.6 In particular, Uusitalo (1985), Bergh (2005) and Brady and Sosnaud (2010) suggest that education systems and labor market outcomes, both determined by government policies, affect the market-based income distribution. For instance, the level of taxes and transfers has an effect on labor supply decisions and thereby on the income distribution.

In addition, the authors indicate that the described measure is exaggerating actual redistribution, because it completely neglects intra-individual redistribution

4Solt (2016) only provides this measure of redistribution for those cases where data quality allows a direct comparison between market and net Gini-coefficients. In particular, Solt (2016) omits observations for countries for which the source data do not include more than three observations of either market- or net-income inequality. This reduces the sample considerable to only 66 countries covering the 1975-2014 period.

5The correlation coefficient between this measure and its absolute version, i.e. Ginimarket−Gininet, equals 0.98. The qualitative results are therefore not expected to differ when using this alternative measure.

6This discussion applies also to our lagged market-based income inequality measures, which is included as a control in the estimation model. Basically, the measure is not capturing inequality in absence of a welfare state but rather inequality before taxes and transfers occur.

within the life-cycle (e.g. pensions). However, we are mainly interested in the change of redistribution levels in the course of increased globalization. In our analysis, we do not judge the absolute level of redistribution, nor do we rank countries by their redistribution levels. Also, we do not restrict our findings to only inter-individual redistribution, but rather to overall redistribution. Hence, the caveat is relevant for correctly interpreting our results, but it is not necessarily undermining them.

In order to capture globalization, we use the KOF Index of Globalization, which was first developed by Dreher (2006) and completely revised and updated by Gygli et al. (2019). The index is published annually by the KOF Swiss Economic In- stitute. The current version consists of data for 209 countries covering 1970-2016.

Further, the index contains three main categories, namely economic, social and po- litical globalization. In our analysis, we focus on the economic component of the index, thereby following Feenstra and Hanson (1996), Ezcurra and Rodr´ıguez-Pose (2013) and Sturm and de Haan (2015). The economic component includes variables such as trade (as a percentage of GDP), foreign direct investment and import bar- riers. An advantage of the new index is its distinction between de facto and de jure measures of globalization. De facto measures, such as foreign direct investments and international trade, describe actual cross-border flows. In contrast, de jure measures capture governmental regulations that affect international transactions, e.g. trade agreements and tariffs. In addition, Gygli et al. (2019) divide economic globalization into trade and financial globalization.7 Examples for variables included in the trade component are actual trade in goods and services (de facto) and trade taxes and tariffs (de jure). Foreign direct investment and international reserves are examples that go into the measure of de facto financial globalization, whereas investments restrictions and international investment agreements are examples representing de jure financial globalization.

A measure of ethnic fractionalization is constructed from the Ethnic Power Re- lations (EPR) Core Dataset of 2014 (Cederman et al., 2010; Vogt et al., 2015). The

7A complete overview of the variables for each component is provided on the website of the KOF Swiss Economic Institute: https://kof.ethz.ch/en/forecasts-and-indicators/indicators/kof- globalisation-index.html, last accessed on March 12, 2020.

database provides annual data on politically relevant ethnic groups, their shares in total population, and their access to executive state power in all countries with a population of at least 500,000 persons. It starts in 1946 and includes 164 coun- tries. Following Alesina et al. (2003), we approximate ethnic fractionalization using a Herfindahl-based index:

EFi,t = 1−X

j

s2j,i,t,

wheresj,i,t is the share of group j over the total population in country iand period t. A country is considered to be more fractionalized when the probability that two randomly drawn individuals belong to the same group is lower (Easterly and Levine, 1997; Alesina et al., 2003; Alesina and La Ferrara, 2005).8 This formula yields an ethnic fractionalization level for each year in a country.

Following the literature presented in Section 2.2, we include several control vari- ables in our baseline model. The log of real GDP per capita strives to account for any effects driven by income levels (see, e.g. Wade (2004); Bergh and Nilsson (2014)). With increased levels of development, redistribution is generally assumed to increase. Data on real GDP and population is provided by the Penn World Table constructed by Feenstra et al. (2015). It provides data on expenditure-side real GDP, using prices for final goods that are constant across countries and over time, measured in millions of 2005 US dollar. We combine the data on GDP and population to construct log real GDP per capita.9

Following Adam and Tzamourani (2016), Bul´ıˇr (2001), Chiu and Molico (2010), Doepke and Schneider (2006a,b), Meh et al. (2010) and Schneider (2014), we include inflation reflecting the potential effect of monetary policy on income inequality and

8In that sense, the ethnic fractionalization measure is related to ethnic diversity, but constitutes a more precise measure by incorporating the population fractions of each politically relevant ethnic group, thereby generating a dynamic measure of ethnic fractionalization that varies over time.

9We test the Kuznets hypothesis by including squared log of real GDP per capita and find no evidence of such a relationship, see Table A.2.2 column (2). We therefore do not include squared log GDP per capita in our redistribution model.

the subsequent reaction of governments in the form of redistributive measures to counteract undesired levels of inequality.10

In order to test the Meltzer and Richard (1981) hypothesis, which states that countries with inherently large levels of inequality redistribute more on average, we include the lagged value of the market-based Gini-coefficient.11 In Table A.2.2 in the appendix, we test additional control variables. The table shows that no additional control variable is significant when added to the main specification described above.12

Table 2.1: Summary Statistics

Variable Obs Mean Std. Dev. Min Max

Relative Redistribution 374 22.89 16.43 -3.78 52.32

Ethnic Fractionalization 374 27.27 23.14 0 87.57

Log GDP per capita 374 9.59 0.82 7.03 11.18

Inflation Rate 374 2.2 5.11 -25.26 14.01

Market-based Gini-Coefficient 374 46.68 6.04 23.92 68.07 Overall Economic Globalization 374 59.45 16.3 15.07 93.15 De facto Trade Globalization 374 46.19 20.68 11.73 98.36 De jure Trade Globalization 374 67.88 20.16 11.77 97.86 De facto Financial Globalization 374 58.96 21.32 6.42 98.63 De jure Financial Globalization 374 64.71 20.54 9.79 91.08

Notes: At most 62 countries are covered in eight 5-year periods from 1975 to 2014.

In our analysis, we focus on medium- to long-term effects of globalization on redistribution. Therefore, we construct averages over 5-year periods. Annual data on income inequality and, thus, on redistribution is noisy (Delis et al., 2014). In particular, the SWIID data contains imputations for missing years, which is adding to the noise. Using data at five-year intervals also alleviates these issues. Table 2.1

10In order to reduce the impact of high inflation periods, we follow e.g. Samarina and Sturm (2014), Dreher et al. (2008, 2009, 2010) and Cukierman (1992) and use the following transformation for the inflation rate: π/(1 +π). In this way extremely high inflation rates do not dominate the variation in this variable and we thereby reduce the likelihood that the results are driven by few extreme observations.

11Note that the lagged value on market-based income inequality is not directly related to the (contemporaneous) redistribution measure and, hence, does not pose a problem on identification or the interpretation of the results.

12Summary statistics for the additional control variables are provided in Table A.2.1.

summarizes the data used. We cover 62 countries for 1975-2014, i.e. eight 5-year periods.13

2.4 Results of the Effects of Globalization and Ethnic Fractionalization on Redistribution

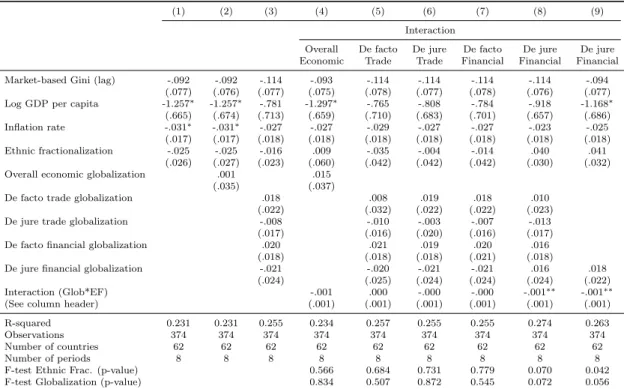

This part of the paper presents the fixed effects estimation results for the effect of globalization and ethnic fractionalization on redistribution. Table 2.2 gives an overview of the effects using the different components of economic globalization described in the data part. The most relevant coefficient in our analysis is the one in front of the interaction term, Globi,t∗EFi,t. A significant estimate would suggest that globalization effects are dependent on ethnic fractionalization.

The first three columns show the effects of ethnic fractionalization (column 1), overall economic globalization (column 2) and the different de facto and de jure globalization measure (column 3) on redistribution without the interaction term included. Though the negative sign is in line with previous literature suggesting less distribution in ethnically fractionalized countries (Gr¨undler and K¨ollner, 2018;

Alesina and La Ferrara, 2005), ethnic fractionalization in general does not have a significant direct effect on redistribution. Economic globalization and its sub- components do not have statistically significant effects on redistribution either.

In column (4) to (9), we show the results for the effects of globalization and ethnic fractionalization when they are interacted. The respective globalization variable is provided in the top row. For instance, we interact de facto trade globalization with ethnic fractionalization in column (5), whereas the other three globalization vari- ables enter merely as control variables. Interestingly, overall economic globalization as well as both trade globalization variables and de facto financial globalization are

13Figure A.2.1 shows histograms of our three key variables. Whereas ethnic fractionalization is quite uniformly distributed (when ignoring the relatively large share of countries that report a zero degree of fractionalization), economic globalization closer matches a normal distribution.

Our measure of redistribution, on the other hand, is twin peaked.

not significant, as indicated by the results of the joint F-test.14 Only de jure finan- cial globalization has a significantly negative interaction term. The F-test suggests joint significance of the de jure financial globalization variable and the interaction term and, thus, a statistically significant total effect of de jure globalization on redistribution.

Table 2.2: Effects on Redistribution

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9)

Interaction

Overall De facto De jure De facto De jure De jure Economic Trade Trade Financial Financial Financial

Market-based Gini (lag) -.092 -.092 -.114 -.093 -.114 -.114 -.114 -.114 -.094

(.077) (.076) (.077) (.075) (.078) (.077) (.078) (.076) (.077) Log GDP per capita -1.257∗ -1.257∗ -.781 -1.297∗ -.765 -.808 -.784 -.918 -1.168∗

(.665) (.674) (.713) (.659) (.710) (.683) (.701) (.657) (.686)

Inflation rate -.031∗ -.031∗ -.027 -.027 -.029 -.027 -.027 -.023 -.025

(.017) (.017) (.018) (.018) (.018) (.018) (.018) (.018) (.018)

Ethnic fractionalization -.025 -.025 -.016 .009 -.035 -.004 -.014 .040 .041

(.026) (.027) (.023) (.060) (.042) (.042) (.042) (.030) (.032)

Overall economic globalization .001 .015

(.035) (.037)

De facto trade globalization .018 .008 .019 .018 .010

(.022) (.032) (.022) (.022) (.023)

De jure trade globalization -.008 -.010 -.003 -.007 -.013

(.017) (.016) (.020) (.016) (.017)

De facto financial globalization .020 .021 .019 .020 .016

(.018) (.018) (.018) (.021) (.018)

De jure financial globalization -.021 -.020 -.021 -.021 .016 .018

(.024) (.025) (.024) (.024) (.024) (.022)

Interaction (Glob*EF) -.001 .000 -.000 -.000 -.001∗∗ -.001∗∗

(See column header) (.001) (.001) (.001) (.001) (.001) (.001)

R-squared 0.231 0.231 0.255 0.234 0.257 0.255 0.255 0.274 0.263

Observations 374 374 374 374 374 374 374 374 374

Number of countries 62 62 62 62 62 62 62 62 62

Number of periods 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8

F-test Ethnic Frac. (p-value) 0.566 0.684 0.731 0.779 0.070 0.042

F-test Globalization (p-value) 0.834 0.507 0.872 0.545 0.072 0.056

Notes: Table shows the effects of different globalization variables on redistribution using the fixed-effects model.

The respective interacted globalization variable is depicted in the top rows. The interaction term combines the respective globalization and the ethnic fractionalization variable. For instance, column (8) shows the results of the effect of de jure financial globalization on relative distribution depending on ethnic fractionalization (captured by the interaction term between de jure financial globalization and fractionalization). Standard errors are clustered at the country level and provided in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. Country- and period-fixed effects not shown. All F-test results are transformed to p-values. F-tests on globalization and ethnic fractionalization denote the joint significance of the interaction term and globalization or ethnic fractionalization, respectively (H0=no effect).

14The F-test KOF Globalization Index shows whether the individual coefficient on globalization and the interaction term are jointly statistically significant. Hence, it indicates whether globalization overall significantly contributes to explaining redistribution. The same applies for the F-test on Ethnic Fractionalization.