Neocolonialism or Balanced Partnership? The State of Agricultural Trade Between the EU and Africa

Volltext

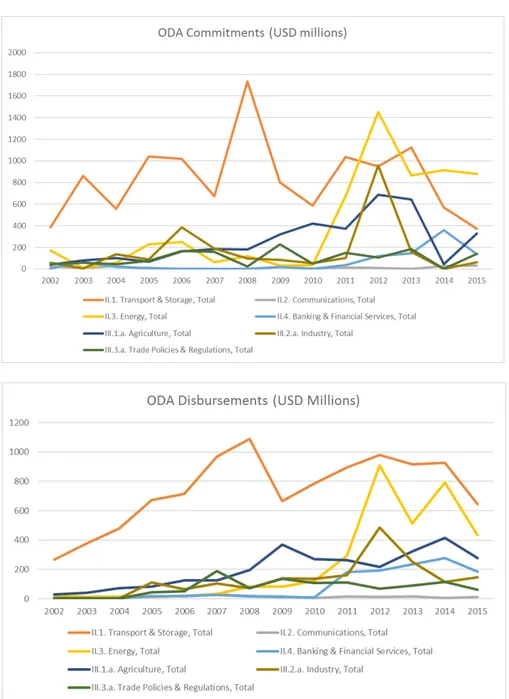

Abbildung

ÄHNLICHE DOKUMENTE

• The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) can play an important role in helping African countries diversify their productive capacities and integrate into regional

There is a pretence that the EUTF money goes to Africa, but it does not, it goes to the European agencies. The EU agencies are fighting over who gets most; they don’t really care

Scenario D offers the possibility of the EPAs forming an integral element of the debate regarding trade and investment, whereas to date they have formed more of a separate

Second, with a view to the ongoing Doha Round, the Commission has reinforced its commitment to support a package for Least Developed Countries (LDCs) as well as “push in the G20,

As part of the signing on 30 October 2016, several declarations of the CETA parties were concluded: Together with the text of the Agreement, a Joint Interpretative Instrument (JII)

The DGB believes commitments on compliance with collective bargaining agree- ments, and social or ecological criteria, should be effectively supported in the regu- lations on

We analyzed GHG emissions caused by fertilizer use, rice cultiva- tion, and livestock production, which account for approximately 88% of total emissions of agricultural production

For example, they have left their monetary union incomplete for ten years, letting economic imbalances grow within the eurozone; they have not invested in a common defence